Abstract

This study compared visual search strategies in adult female volleyball players of three levels. Video clips of the attack of the opponent team were presented on a large screen and participants reacted to the final pass before the spike. Reaction time, response accuracy and eye movement patterns were measured. Elite players had the highest response accuracy (97.50 ± 3.5%) compared to the intermediate (91.50 ± 4.7%) and novice players (83.50 ± 17.6%; p<0.05). Novices had a remarkably high range of reaction time but no significant differences were found in comparison to the reaction time of elite and intermediate players. In general, the three groups showed similar gaze behaviour with the apparent use of visual pivots at moments of reception and final pass. This confirms the holistic model of image perception for volleyball and suggests that expert players extract more information from parafoveal regions.

Keywords: anticipation, visual search, expertise, volleyball, holistic model of image perception

INTRODUCTION

In the past decades, many studies on visual search behaviour in ball and racquet sports have significantly extended our knowledge on the information pick-up and processing that precede a fast and correct decision during the game [1–7]. Although differences between sports exist due to the specific nature of each game, the general conclusion is that expertise is related to earlier pick-up of relevant information. As a result, expert players are able to adequately anticipate an opponent's action. This general rule has been corroborated in a wide variety of sports including soccer, tennis, badminton and others [8, 9, 4, 10, 11].

In spite of the body of knowledge available in these sports, only a few experiments have focused on expert-novice differences in the visual search patterns of volleyball players. Volleyball is a team sport like soccer and basketball, but unlike soccer and basketball, players are not allowed to physically interfere with the preparation of an attack by the opponent team. The response to the opponent's attack consists of either blocking the spike at the net, or defending further away from the net. Both tasks are highly time-constrained and are believed to rely to a great extent on anticipation [12].

These particular characteristics render the mere generalization of visual search behaviour in other team sports to volleyball problematic. Research on the use of visual information in volleyball has often been restricted to isolated actions during which one or a limited number of players are involved. At the level of the individual player, preparatory movements of the opponent contain visual cues that can help predict the direction and speed of the ball after the serve or the spike [13]. These cues seem similar to the visual cues in preparatory movements in racket games. In general, most actions in racket games have a proximal-to-distal development, and visual cues are usually found in this order, so gaze is directed in a proximal-to-distal sequence [14, 5]. In a volleyball situation, occlusion experiments showed that experienced players are able to predict pass and serve direction better than novice players [15, 16]. This indicates that experienced volleyball players ‘read’ the opponents’ play better than novice players. Herandez et al. [17] suggested that the horizontal vertex-ball distance can predict setting direction, implying that this information is available before the ball is launched. In an eye-tracking experiment, experienced volleyball players indeed directed their gaze more to the setter than novice players, who tended to watch the whole trajectory of the ball [18]. Experienced players only track the initial part of the ball trajectory. Then their eyes ‘shoot ahead’ to the final portion of the trajectory. This gaze strategy has been described previously for tennis, table tennis and cricket, where experienced players made an anticipatory saccade to the bounce point of the ball [19, 20, 21, 3].

While the preparatory actions in tennis or badminton consist of only one person who executes the counter attack (even in a double game), in volleyball three contacts can be made and all of the six players can be involved in the attack. This means that instead of one action, multiple actions have to be analysed to detect advanced cues. When the ball is in the opponents’ court, a volleyball player needs to analyse the quality of reception, the setting possibilities, the pass quality and the attackers’ movements. Since the number of opponents has an effect on the visual search behaviour in soccer [22], and given that the within-team tactics might also provide information on the nature of the opponents’ attack, it is not surprising that Afonso et al. [23, 24] recently reported slightly different gaze behaviour when participants played in a six-versus-six situation. In this in situ experiment, highly skilled female volleyball players employed more fixations to a greater number of locations and spent more time fixating functional spaces (i.e. areas that are intermediate to a number of cues of interest) before and during ball contact than less skilled participants. This suggests that highly skilled volleyball players retrieved a greater amount of information by using their peripheral vision more efficiently.

However, these experiments summarize the gaze behaviour of an entire game sequence in one measure. Since picking up the right information at the right time is essential for time-constrained sports such as volleyball, it seems valuable to focus on the gaze behaviour over the course of a game sequence. Therefore, this study focuses on the course of visual search behaviour of volleyball players of different levels who watched a full attack sequence in a blocking task. Apart from experienced players being faster and more accurate in their reaction, we also expected to find certain gaze patterns at specific moments. The expected gaze pattern is described in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

EXPECTED GAZE LOCATION AT KEY MOMENTS FOR ELITE AND NOVICE PARTICIPANTS

| Time course | Gaze location Elite | Gaze location Novice | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ball on screen | Ball - Receiver | ||

| (A) | Early Ball detection | Late ball detection | Allard & Starkes [40] |

| (B) | Eyes ‘shoot ahead’ to final part of ball flight | Sibley & Etnier [41] | |

| Piras et al. [18] | |||

| Reception | Receiver - Ball | ||

| (C) | Earlier tracking onset | Late tracking onset | Vickers & Adolphe [13] |

| (D) | ‘Shoot ahead’ to setter | ‘ball watching’ | Piras et al. [18] |

| Ball Highest Point | Ball - Setter | ||

| (E) | Setter, in proximal-to-distal sequence | Shoot ahead to setter | Wright et al. [16] |

| Piras et al. [18] | |||

| Set | Setter - Attacker | ||

| (F) | Inter-event fixation | Setter | Vickers 2007 [35] |

| (G) | Attackers | ||

| End eye tracking: | |||

Note: The elite group was also expected to use more ‘inter-event fixations’ throughout the volleyball sequence [23].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

In total, 37 adult women participated in the study and were assigned to an elite, an intermediate or a novice group based on their volleyball experience and expertise. The elite group consisted of ten professional female volleyball players, who played for the same volleyball team at the highest division in Belgian female competition. The team trains 20 hours a week and was also competing in the European Challenge Cup at the time of the study. The intermediate group consisted of ten female volleyball players from the third, fourth or fifth division of Belgium competition (with eight divisions in total) and trained less than ten hours a week. The novice group consisted of 17 female bachelor students of physical education from Ghent University. They had no experience in volleyball at a competitive level but were familiar with the basics of the game.

A significant difference was found for weight and height but not for age between the three groups (resp.: F2,36=14.097; p<0.01; F2,36=21.207; p<0.01; F2,36=1.106; p = 0.342). The elite and intermediate groups were heavier and taller than the novice group. The elite group was taller, but not heavier than the intermediate group (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

AGE, BODY HEIGHT AND BODY MASS OF THE PARTICIPANTS

| Elite | Intermediate | Novice | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 20.0 ± 1.2 | 20.9 ± 1.8 | 20.1 ± 1.6 |

| Body height (cm) | 181.5 ± 4.8 a | 175.9 ± 3.4 a | 169.4 ± 5.3 a |

| Body mass (kg) | 73.1 ± 5.1 a | 69.7 ± 3.9 b | 62.8 ± 5.7 a, b |

Note: Means in the same row with the same superscript are significantly different (p < 0.01).

Film fragments

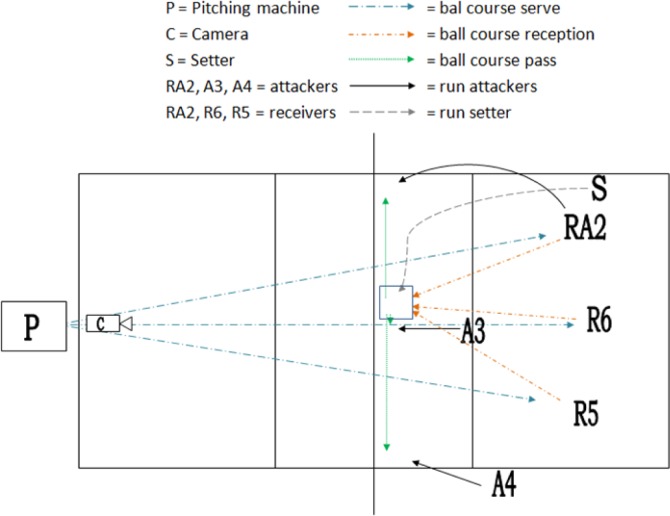

Attack sequences were recorded with experienced players (intermediate level) according to a fixed scenario. A high-speed camera (Casio 100) was placed on the back line of a volleyball court, recording the actions of six female volleyball players. Each fragment consisted of a serve, delivered by a pitching machine (JUGS; placed at a height of 1.42 m) to obtain maximal inter-trial consistency of the serves, a reception from one of the three receivers (RA2, R6 and R5 in Figure 1), and a front, middle or back pass from the setter (A4, A3, or RA2 in Figure 1). This ‘complex 1’ game sequence is a basic volleyball play which is used throughout all experience levels. Each of the nine situations (3 serve x 3 pass directions) was successively executed until at least 3 good fragments had been filmed. A fragment was rated ‘good’ if the reception was delivered in a 1 m by 1 m square (see Figure 1) and if the pass was given so that the attackers could spike successfully. The 20 final clips included five passes forward (to A4), five passes in the middle (to A3) and ten backward passes (to RA2). The 20 fragments were edited in such a way that each fragment started when the ball appeared in the camera field of view and ended the frame before ball-hand contact during the spike. A 3-2-1 countdown was added prior to the start of each fragment.

FIG. 1.

BIRD'S-EYE VIEW OF THE FILMING SETUP AND NINE POSSIBLE VOLLEYBALL ATTACK SEQUENCES (THREE RECEIVERS X THREE ATTACKERS)

Apparatus

Film fragments were played from an iMac and projected on a 4.35 m wide, 2.47 m high screen. Participants stood on pressure sensors at a distance of 4.55 m in front of the screen. Sensors were connected to a computer using SIMI software to calculate reaction times. A scene camera filmed the screen and participants and was synchronized with the SIMI recordings.

For the registration of the eye movements, the Applied Science Laboratories Eye Tracking System, model 501 Head Mounted Optics (ASL, Bedford, MA) was used. This system recorded the left eye movements at a frequency of 60 Hz with an infrared-sensitive camera using pupil position and corneal reflection. Using the computer program Eyenal, the eye movements were linked to the video fragments. This resulted in video fragments with a crosshair superimposed, representing the point of gaze.

Procedure

After giving written informed consent, each participant was tested individually. The test leader used a standardized PowerPoint presentation to explain the test purpose and procedure. At the end of the explanation five video fragments were shown as familiarization trials. Each participant was then shown the 20 video clips of volleyball situations, which were randomized but in the same order for all participants, and was asked to react as quickly and accurately as possible to the pass direction by moving in the same direction of the pass (imitating the movement of a counter). The participants were asked to look at the countdown which preceded each fragment so that the gaze direction was towards the centre of the screen at the beginning of each trial. The experimental procedure was approved by the Ghent University Hospital Ethical Committee.

Dependent measures

Response accuracy was expressed as the number of trials in which the subject made her displacement in the right direction, i.e. the direction of the pass towards the player who will perform the attack. This was evaluated on-line by the experimenter. Reaction time (RT) was defined as time from setter-ball contact until the release of the pressure sensor by the participants.

The eye tracking system recorded the eye movements of the participants and provided a video of the volleyball sequence with a crosshair representing the gaze location, superimposed on the volleyball film clip. Five areas of interest (AOIs) were determined: Ball, Receiver, Setter, Attacker and an Inter-event fixation (gaze on a point in space which does not contain a ‘target’ but is in the middle of several relevant sources of visual information [18]. Indistinct data were coded as NoData.

Pilot work showed that gaze was usually switched at three specific moments: the moment of ball-receiver contact (R); the moment the ball reaches its highest point between receiver and setter (BHP); and the moment of ball-setter contact (P). To normalize the twenty film frames to these key moments, the clips were split into 36 time frames (T1–T36) in a way that four blocks could be distinguished: start-R, R-BHP, BHP-P and P-end. Using the gaze location videos, gaze location was assigned manually to one of the AOIs for each time frame. For each AOI [6] a percentage of gaze was calculated per time frame [36] for each participant (example of data process in Figure 2).

FIG. 2.

EXAMPLE OF DATA PROCESS FOR ONE PARTICIPANT

Note: Gaze was analysed per time frame for each of the 20 video clips per participant (upper part). Percentage of gaze towards each AOI was calculated for each time frame per participant (lower part), BHP indicates the moment the Ball reaches its Highest Point between receiver and setter.

Data analysis

Data normality and equality of variance were tested for all variables using the Shapiro-Wilk test and Levene's test, respectively. Since these tests gave significant results for the RT, accuracy and most of the gaze percentages, non-parametric tests were used instead of parametric tests. To test group differences in RT, accuracy and gaze behaviour, the Kruskal-Wallis test was used as the non-parametric equivalent of the ANOVA test. Since this test only reports general inter-group differences, further differences between the individual groups were analysed with the Mann-Whitney U test, which is the non-parametric equivalent of the independent samples t-test. The standard level of significance was set as p < 0.05. RT data of one novice participant were lost.

RESULTS

Accuracy and reaction time

Group differences were found for accuracy and for RT, although differences in RT did not reach significance (p = 0.006 and p = 0.068, respectively). The elite group had a significantly higher accuracy than the intermediate and novice group (Z2,34 = -2.836; p<0.01 and Z2,34 = -2.742; p<0.01, respectively). No difference in accuracy was found between the intermediate and novice group (Z2,34 = -1.302; p = 0.204). Both the elite and intermediate group had a shorter reaction time than the novice group but differences of novices did not reach significance (Z2,33 = -1.953; p = 0.053 and Z2,33 = -1.877; p<0.060, respectively). No difference in RT was found between elite and intermediate players (Z2,33 = -0.304; p = 0.796) (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

REACTION TIME AND ACCURACY DATA

| Elite (n=10) | Intermediate (n=10) | Novice (n=17) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy (%) | |||

|

| |||

| Mean +/- SD | 97.50 ± 3.54 a,b | 91.50 ± 4.74 a | 82.06 ± 18.03 b |

| Range | 90 – 100 | 80 – 95 | 40 – 100 |

|

| |||

| RT (ms) | |||

|

| |||

| Mean +/- SD | 243 ± 59 c | 246 ± 31 d | 362 ± 246 c,d |

| Range | 167 – 355 | 200 – 309 | -134 - 767 |

Note: superscripts a & b indicate a significant difference (p < 0.05) between the values where the superscripts are added. superscripts b & c indicate 0.05 < p < 0.1

Gaze location

Figure 3 shows an overview of the significance of the Kruskal-Wallis tests per time frame and per AOI; further significance among groups is reported below. The three groups all showed a similar time course of gaze behaviour. Gaze switched from the receiver to the ball after reception and shifted to the setter before the ball reached its highest point. As the ball came closer to the setter, more inter-event fixations were used. Once the pass had been given, gaze was directed mostly to the attacker.

FIG. 3.

TIME COURSE OF GAZE LOCATION FROM TIME FRAME T1 (BALL ON SCREEN) TO T36 (ATTACKER-BALL CONTACT)

Note: Standard deviation is shown at peak moments of each AOI. ANOVA results (group differences) are given in colour code: Green: p < 0.05; Orange: 0.05 < p < 0.1; White: p > 0.1; Expected gaze location as given in Table 1 is represented by thick boxes and the corresponding letter: (A)-(I)

No earlier ball detection was found in experienced players than in intermediates and novices (A in Figure 3). Instead, all participants retained the central inter-event fixation for a brief moment and then switched gaze to the receiver (B on Figure 3).

The elite group used fewer inter-event fixations than the novice group from T3 until T8 and fewer than the intermediate group from T4 until T7. Instead, the elite group looked more to the receiver than the novice group from T3 until T8, and than the intermediate group from T5 until T8. From T3 until T6 the elite group also had a higher percentage of looking towards the attackers than the novice and intermediate group. No differences in the use of inter-event fixations were found between the novice and the intermediate group for this period (B in Figure 3).

In the time frames 6 and 7, The novice and intermediate group spent slightly more time watching the setter than the elite group but no difference was found between the intermediate and the novice group.

Immediately preceding and during the reception (T6-11), novices and intermediates looked more to the ball than the elite group but no significant differences were found between intermediates and novices.

After the reception (T11-17), ball tracking was not found to be earlier for the experienced players than for the intermediates or novices and no significant difference was found in ‘ball watching’ (C in Figure 3). Elite players looked significantly more to the attackers than the novices and the intermediate group. All three groups started switching gaze from ball to setter before BHP (D on Figure 3) and all groups looked mainly at the setter after BHP (T19-23; E on Figure 3). However, experienced players seem to use more inter-event fixations towards the moment of the pass (T21-25; F on Figure 3). Post hoc analysis revealed a significant difference between the elite group and the novice group for T23-T25, but differences from the intermediate group were not significant.

After the pass (T28-36; G on Figure 3), elite players looked significantly more to the attackers than the intermediates and novices, who used more inter-event fixations (T30-36). However, the percentage of indistinct gaze behaviour was also higher for novices and intermediates (T28-36).

DISCUSSION

The general aim of this study was to analyse reaction time, accuracy and time course of gaze behaviour of elite, intermediate and novice adult female volleyball players when reacting as a middle blocker on a screen projected complex 1 situation.

Reaction time and accuracy

It has been demonstrated that the effective use of advanced visual cues leads to better anticipation of the opponents’ actions [25, 26]. Therefore, a shorter RT and higher accuracy were expected for the elite group compared to the intermediate and the novice group [9, 27–29]. In the current study, elite players indeed had superior accuracy, but no difference was found in RT between elite and intermediate players. This could be a consequence of the task constraints of the volleyball block. A comparison can be made between a blocking task in volleyball and stopping a penalty in soccer [30]. If the athlete waits longer to make a decision, he can gather crucial information about the opponents’ action but will have less time to complete his own reaction. Expert volleyball players, however, are trained to execute their actions fast, which gives them the possibility to react later without dropping the quality of the counter. Such an explanation is supported by the large standard deviation and range in RT in the novice group, which shows that even negative RTs regularly occurred. This means that novice players often react when the information necessary for an adequate decision is not yet available, and thus rely on anticipation. They however lack episodic and task-related expertise to successfully anticipate [11, 31], which is reflected in their lower accuracy scores. Reacting too early, with a negative impact on performance, is a phenomenon that is often observed in sports [32, 30]. Analysis of the visual search patterns can shed further light on the decision making process that forms the basis of an accurate response at the right time.

Time course of gaze behaviour

Unlike what was expected, but in line with previous findings of Abernethy [8] for badminton players, few differences were found when gaze behaviour of elite, intermediate and novice players was compared. Although high standard deviations indicate that some participants regularly adapted their gaze pattern, a general visual strategy was used.

In contrast to the expected time course of gaze behaviour, gaze was not directed to the ball before participants looked at the receiver (A in Table 1 and Figure 3). Instead of tracking the ball, gaze was held briefly at a central location on the screen, after which attention was immediately directed to the receiver. In racket sports such as tennis, table tennis and badminton, it has already been suggested that the final part of the ball flight does not contain much information [19, 20, 33, 5]. Since the ball was already on its way down when it appeared on the screen, participants probably extracted sufficient information peripherally from their first central fixation to predict ball direction and directed their gaze immediately to the next ‘bounce point’, being the receiver. In contrast with the findings of Afonso et al. [23], during the first part of the sequence the elite group spent less time fixing the ‘functional space’ (inter-event fixations) than the intermediate and the novice group. However, this might have been due to a more efficient use of peripheral vision. Since the first inter-event fixation was merely an artefact of the central location of the countdown, a quicker switch of gaze towards the receiver could indicate that the elite group interpreted the scene faster than the intermediate and the novice group.

After the reception, participants briefly tracked the ball and then switched their focus of attention from the ball to the setter even before the ball reached its highest point (D in Figure 3). This ‘visual shoot ahead’ was previously described by Land for table tennis, where the timing of the predictive saccade was closely linked to the highest point of the ball's trajectory [20]. In the experiment of Piras et al. [18] volleyball players also fixated the next bounce point, being the setter's hands. However, these experiments included only one opponent. Based on the findings of Vaeyens et al. [10], we expected the extra opponents in current experiment to have an impact on the visual behaviour of the participants. Surprisingly, the results show few fixations on the attacking players. Apparently, participants did not pay much attention to the attacking players or they used peripheral vision to track opponents’ movements. Unfortunately, based on only eye movement results, it is not possible to determine in what way visual information is gathered peripherally. Viviani referred to ‘the ability of relocating attention without moving the point of fixation’ as the central dogma of eye movement research (in: [11]). Basically, it emphasizes the distinction between looking and seeing.

Although it is possible that attackers were looked at peripherally, the fact that gaze was directed mainly towards the setter indicates that participants expect important visual cues in this area. Hernandez et al. [17] suggested that the distance from the setter's shoulders to his hands can be a good predictor for set direction. So, important information of pass direction can indeed be found in the setter's movements prior to the pass.

In the current study, the hands were not a separate AOI as the setter was seen as one single area. But the results show that in most trials an inter-event fixation was made immediately after fixating the setter. This inter-event fixation was almost always directed to the future ball-setter contact point, just above the setter's hands, and has been reported by Afonso et al. [23] to be more frequent in highly skilled volleyball players than in less skilled players. The visual shift from setter to the future ball position is similar to the proximal to distal shift of fixation location found in racket sports [5] and in goalkeepers when stopping a penalty [4]. This underpins the hypothesis that volleyball players use the same strategy in a blocking situation as goalkeepers use in penalty stopping.

After the final pass, the elite group looked significantly more towards the attackers than the intermediate and novice group. In the current experiment the task was to react to the setter. Probably the intermediate and novice group neglected the final part of the video since they had already reacted to the setter. The elite players however are used to switch their gaze immediately to the attacker after the pass to analyse the spiker's attack. So this difference could be caused by the procedural routine of the elite players.

General discussion

Apparently, more experienced players do not react faster and more accurately because they have a different visual strategy. However, a similar gaze pattern does not necessarily mean that the same visual information has been processed. Possibly, experienced players are able to extract more information from perifoveal regions than novice players.

Although all groups mainly looked at the receiver before the reception was taken, some of the intermediate and novice players already looked at the ball as well. In the elite group on the other hand, none of the participants fixated the ball before reception was taken. This shows that the elite group has a very consistent visual strategy to analyse the reception. A ‘visual pivot’ was used to analyse this player 's movements and to track the ball towards this player peripherally at the same time. In the intermediate and novice group on the other hand, some participants seem to try to track the ball towards and away from the receiver.

All groups use a similar visual pivot when the final pass is given. However, elite players seemed to watch the functional space between the ball and the setter's hands to analyse pass direction, while intermediate and novice players looked more to the setter himself. This gaze behaviour has been described previously in various situations [3, 22, 34] and for elite volleyball players when looking to a jump serve [35 p122] and when analysing a setter in situ [23].

Since there was no clear distinction in gaze behaviour between the groups, differences in reaction time and accuracy must have been the result of a superior information processing and decision making system. The use of visual pivots at the moment of reception and pass also suggests that participants retrieved a great amount of information through the use of peripheral vision. According to the holistic model of image perception [36, 37], experts can extract information from widely distanced and parafoveal regions. So it appears that the three groups used a similar gaze strategy, but that elite players are able to subtract more relevant information by using an extended visual span and are able to link this information better to task-specific and procedural knowledge of the volleyball game play.

The similar gaze strategy in the three groups could have been supported by video-based stimuli. In a real blocking situation, volleyball players stand immediately in front of the net, which makes it necessary to make large head movements to see the attacking players at both corners of the net. In the current experiment however, participants could see both sides of the net with minimal head movements. In a real set-up, elite players would probably also benefit more from their better visuo-spatial attentional processing skills [38, 39]. Therefore, differences in gaze behaviour between the groups would possibly have been larger in an in situ blocking task. Nevertheless, differences in gaze behaviour of the current experiment also reflect different information processing in the elite group than in the intermediate and the novice group. Furthermore, the current results are in line with findings of the in situ experiment of Afonso et al. [23].

Practical implications

Current insights into the visual information processing of novice and elite volleyball players may help trainers to improve visual skills of young players. It should be noted however that the proposed visual search sequence is not per se the only correct way to ‘read’ the opponents’ game. Many factors, including team tactics, opponents’ characteristics, etc. can be of interest for the anticipatory visual search.

Furthermore, knowledge of the differences in visual behaviour of elite and sub-elite players may be used to develop talent identification test procedures. It is however still open to question whether a larger visual span is due to extensive training or an innate ability.

CONCLUSIONS

This study showed that elite female volleyball players have a higher accuracy when responding to screen-projected attacks of the opponent team when compared to novice players. The intermediate group reacted as quickly as the elite group but had a lower accuracy. Time course analysis of the gaze behaviour however showed a very similar gaze pattern for the three experience levels with the apparent use of visual pivots at moments of reception and final pass. This confirms the holistic model of image perception for volleyball and suggests that expert players extract more information from parafoveal regions.

Acknowledgements

We thank Bram Verborgt, Annelies Janssens, Jort Verdick, Wouter Eloot and Silke Veeckman for helping with data collection. We also thank Stijn Morand and VDK Gent for supporting our study.

Conflict of interest

The authors of the manuscript declare no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abernethy B. Visual search in sport and ergonomics its relationship to selective attention and performer expertise. Hum Perform. 1988;1:205–235. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bard C, Fleury M. Analysis of visual search activity during sport problem situations. J Hum Mov Stud. 1976;3:214–222. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ripoll H, Fleurance P. What does keeping one's eye on the ball mean? Ergonomics. 1988;31:1647–1654. doi: 10.1080/00140138808966814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Savelsbergh GJP, van der Kamp J, Williams AM, Ward P. Anticipation and visual search behaviour in expert soccer goalkeepers. Ergonomics. 2005;48:1686–1697. doi: 10.1080/00140130500101346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singer RN, Williams AM, Frehlich SG, Janelle CM, Radlo SJ, Barba DA, Bouchard LJ. New frontiers in visual search: an exploratory study in live tennis situations. Res Q Exerc Sport. 1998;69:290–296. doi: 10.1080/02701367.1998.10607696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vickers JN. Visual control when aiming at a far target. Perception. 1996;22:342–354. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.22.2.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams AM, Davids K, Burwitz L, Williams JG. Visual search strategies in experienced and inexperienced soccer players. Res Q Exerc Sport. 1994;65:127–135. doi: 10.1080/02701367.1994.10607607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abernethy B. Visual search strategies and decision-making in sport. Int. J. Sport Psychol. 1991;22:189–210. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mann DTY, Williams AM, Ward P, Janelle CM. Perceptual-cognitive expertise in sport: a meta-analysis. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2007;29:457–478. doi: 10.1123/jsep.29.4.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vaeyens R, Lenoir M, Williams AM, Mazyn L, Philippaerts MR. The effects of task constraints on visual search behavior and decision-making skill in youth soccer players. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2007;29:147–169. doi: 10.1123/jsep.29.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams AM, Janelle CM, Davids K. Constraints on the search for visual information in sport. Int J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2004;2:301–318. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cañal-Bruland R, Mooren M, Savelsbergh GJP. Differentiating experts’ anticipatory skills in beach volleyball. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2011;82:667–74. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2011.10599803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vickers JN, Adolphe RM. Gaze behaviour during a ball tracking and aiming skill. Int J Sports Vis. 1997;4:18–27. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abernethy B, Gill PG, Parks SL, Packer ST. Expertise and the perception of kinematic and situational probability information. Perception. 2001;30:233–252. doi: 10.1068/p2872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Starkes JL, Edwards P, Dissanayake P, Dunn T. A new technology and field test of advance cue usage in volleyball. Res Q Exerc Sport. 1995;66:162–167. doi: 10.1080/02701367.1995.10762223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wright DL, Pleasants F, Gomez-Meza M. Use of advanced visual cue sources in volleyball. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 1990;12:406–414. doi: 10.1123/jsep.12.4.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hernandez E, Urena A, Miranda MT, Ona A. Kinematic analysis of volleyball setting cues that affect anticipation in blocking. J Hum Mov Stud. 2004;47:285–301. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Piras A, Lobietti R, Squatrito S. A study of saccadic eye movement dynamics in volleyball: comparison between athletes and non-athletes. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2010;50:99–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farrow D, Abernethy B. Do expertise and the degree of perception-action coupling affect natural anticipatory performance? Perception. 2003;32:1127–1139. doi: 10.1068/p3323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Land MF, Furneaux S. The knowledge base of the oculomotor system. Philos Trans R Soc. 1997;352:1231–1239. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1997.0105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Land MF, Mcleod P. From eye movements to actions: how batsmen hit the ball. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:1340–1345. doi: 10.1038/81887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vaeyens R, Lenoir M, Williams AM, Philippaerts MR. Mechanisms underpinning successful decision making in skilled youth soccer players: an analysis of visual search behaviors. J Mot Behav. 2007;39:395–408. doi: 10.3200/JMBR.39.5.395-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Afonso J, Garganta J, Mcrobert A, Williams AM, Mesquita I. The perceptual cognitive processes underpinning skilled performance in volleyball: Evidence from eye-movements and verbal reports of thinking involving an in situ representative task. J Sport Sci Med. 2012;11:339–345. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Afonso J, Garganta J, Mcrobert A, Williams AM, Mesquita I. Visual search behaviours and verbal reports during film-based and in situ representative tasks in volleyball. Eur J Sport Sci. 2014;14:177–184. doi: 10.1080/17461391.2012.730064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shim J, Carlton LG, Chow JW, Cae WS. The use of anticipatory visual cues by highly skilled tennis players. J Mot Behav. 2005;37:164–175. doi: 10.3200/JMBR.37.2.164-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smeeton NJ, Williams AM, Hodges NJ, Ward P. The relative effectiveness of various instructional approaches in developing anticipation skill. J Exp Psychol. 2005;11:98–110. doi: 10.1037/1076-898X.11.2.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nougier V, Rossi B. The development of expertise in orienting of attention. Int J Sport Psychol. 1999;30:246–260. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ripoll H, Kerlirzin Y, Stein JF, Reine B. Analysis of information processing, decision making, and visual strategies in complex problem solving sport situations. Hum Mov Sci. 1995;14:325–349. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zwierko T, Osiński W, Lubiński W, Czepita D, Florkiewicz B. Speed of Visual Sensorimotor Processes and Conductivity of Visual Pathway in Volleyball Players. J Hum Kinet. 2010;23:21–27. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Savelsbergh GJP, Williams AM, van der Kamp J, Ward P. Visual search, anticipation and expertise in soccer goalkeepers. J Sports Sci. 2002;20:279–287. doi: 10.1080/026404102317284826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Henderson J. Human gaze control during real–world scene perception. Trends Cogn Sci. 2003;7:498–504. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2003.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oudejans RR, Michaels CF, Bakker FC. The effects of baseball experience on movement initiation in catching fly balls. J Sports Sci. 1997;15:587–595. doi: 10.1080/026404197367029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Savelsbergh GJP. Tussen de Linies spelen; Oratie, Amsterdam: Faculteit der Bewegingswetenschappen, Vrije Universiteit. Amsterdam; 2009. p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Higuchi T, Cinelli ME, Patla AE. Gaze behavior during locomotion through apertures: the effect of locomotion forms. Hum Mov Sci. 2009;28:760–71. doi: 10.1016/j.humov.2009.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vickers JN. Perception, cognition, and decision training: the quiet eye in action; Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics Publishers; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kundel HL, Nodine CF, Conant EF, Weinstein SP. Holistic component of image perception in mammogram interpretation: Gaze-tracking study. Radiology. 2007;242:396–402. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2422051997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gegenfurtner A, Lehtinen E, Säljö R. Expertise differences in the comprehension of visualizations: a meta-analysis of eye-tracking research in professional domains. Educ Psychol Rev. 2011;23:523–552. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alves H, Voss MW, Boot WR, Deslandes A, Cossich V, Salles JI, Kramer AF. Perceptual-cognitive expertise in elite volleyball players. Front Psychol. 2013;4:1–9. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jafarzadehpur E, Aazami N, Bolouri B. Comparison of saccadic eye movements and facility of ocular accommodation in female volleyball players and non-players. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2007;17:186–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2005.00535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Allard F, Starkes J. Perception in sport: Volleyball. J Sport Psychol. 1980;2:22–23. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sibley B, Etnier J. Time course of attention and decision making during a volleyball set. Res Q Exercise Sport. 2004;75:102–106. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2004.10609138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]