Abstract

Antimicrobial efficacy and toxicity varies between individuals owing to multiple factors. Genetic variants that affect drug-metabolizing enzymes may influence antimicrobial pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, thereby determining efficacy and/or toxicity. In addition, many severe immune-mediated reactions have been associated with HLA class I and class II genes. In the last two decades, understanding of pharmacogenomic factors that influence antimicrobial efficacy and toxicity has rapidly evolved, leading to translational success such as the routine use of HLA-B*57:01 screening to prevent abacavir hypersensitivity reactions. This article examines recent advances in the field of antimicrobial pharmacogenomics that potentially affect treatment efficacy and toxicity, and challenges that exist between pharmacogenomic discovery and translation into clinical use.

Keywords: antibacterials, antifungals, antimalarials, antivirals, pharmacogenomics

Background

Sources of variation

Antimicrobial agents have dramatically reduced mortality and morbidity from communicable diseases [1,2]. Interindividual variability in treatment efficacy, effectiveness and toxicity is governed by complex relationships between host, microbe and drug factors (Figure 1) [3–5]. Within the human host, antimicrobial agents have distinct pharmacokinetic (PK; absorption, distribution, elimination and metabolism [ADME]) and pharmacodynamic (PD) profiles. Antimicrobials may be eliminated largely unchanged in stool or urine (e.g., vancomycin), or may undergo active metabolism. Drug metabolism is mediated by phase I enzymes such as oxidative CYP450 (CYP) enzymes or phase II enzymes such as glutathione-S-transferases (GST) and UDP-glucuronosyltransferases (UGT), which produce pharmacologically active, inactive or reactive/toxic metabolites. In addition, disposition of many antimicrobials is affected by intestinal, hepatic and renal membrane transporters (Table 1) [6,7]. Individual differences in genes encoding ADME proteins may lead to variable expression and/or activity of these proteins leading to differences in drug exposure. However, whether this translates into clinically relevant differences in efficacy and toxicity depends on other antimicrobial properties such as the therapeutic window and host PD factors [8].

Figure 1. Complex relationships between various drug, pathogen and host factors affecting antimicrobial treatment outcome.

ADR: Adverse drug reaction; PD: Pharmacogenomics; PK: Pharmacokinetics

Modified and reproduced with written permission from Pharmacogenomics and Personalized Medicine [9].

Table 1.

Drug uptake transporters and their interactions with antimicrobial agents.

| Family | Member | Tissue distribution | Cellular localization | Antimicrobial substrates | Important roles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SLCO | OATP2B1 | Liver, intestine, placenta | Basolateral | Benzylpenicillin | CNS distribution |

| OATP1B1 | Liver | Basolateral | Benzylpenicillin, rifampin | Hepatic uptake | |

| OATP1B3 | Liver | Basolateral | Rifampin | Hepatic uptake | |

|

| |||||

| SLC22 | OAT1 | Kidney, brain | Basolateral | Cidofovir, acyclovir, tetracycline | Renal uptake |

| OAT3 | Kidney, brain | Basolateral | Valacyclovir, tetracycline | Renal uptake | |

| OAT4 | Kidney, placenta | Apical | Tetracycline | Renal secretion | |

| OCT1 | Liver, brain, small intestine | Basolateral | Quinine | Hepatic/renal uptake | |

|

| |||||

| ABCB | MDR1 (P-gp) | Kidney, liver, brain, small intestine | Apical | Erythromycin, protease inhibitors, voriconazole, mefoquine, quinine, chloroquine | Oral absorption, renal secretion, biliary excretion, CNS distribution |

|

| |||||

| ABCC | MRP2 | Liver, kidney, small intestine | Apical | Ampicillin, ceftriaxone, tenofovir | Biliary excretion, renal secretion |

ABC: Adenosine triphosphate-binding cassette; MDR: Multidrug resistance protein; MRP: Multidrug resistance-associated protein; OCT: Organic cation transporter; OAT: Organic anion transporter; OATP: Organic anionic transporting polypeptide.

Reproduced with permission from [6], Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, Macmillian Publishers Ltd © (2005)

Adverse drug reactions (ADRs) to antimicrobials, as with other drugs, can be clinically and epidemiologically classified as either type A or type B reactions [10]. Type A reactions are related to intrinsic pharmacologic properties of a drug that tend to be predictable based on PK/PD parameters but affected by host ecology and pharmacogenomics (Figure 1). Type B reactions are predominantly allergic or immunologically mediated, which have been commonly classified according to Gell and Coombs (Table 2) [11]. Type I (IgE-mediated reactions, such as penicillin allergy) and type IV (delayed hypersensitivity, largely T-cell mediated) reactions are most relevant to antimicrobials. Recently these have been associated with variation in host MHC molecules and T-cell receptors, via hapten and nonhapten pathways [12]. Increasing evidence suggests that specific MHC class I HLA-B alleles in particular may predispose to severe T-cell mediated drug hypersensitivity [13].

Table 2.

Gell and Coombs classification for hypersensitivity reactions.

| Classification | Effector response | Immunopathologic mechansims | Clinical features | Time of onset | Examples of associated antimicrobials |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type I, immediate | IgE | Mast cell/basophil degranulation and histamine release | Urticaria, angioedema, anaphylaxis | Immediate (<30 min) after exposure | β-lactams, fluoroquinolones |

| Type II, cytotoxic | IgM, IgG, complement | FcR-dependent cell destruction | Cytopenias, nephritis | 1–2 weeks after exposure† | β-lactams, quinine |

| Type III, immune complex | IgM, IgG, complement | Immune complex deposition in organs | Serum sickness, vasculitis | 1–2 weeks after exposure† | Penicillin, cefaclor (serum-sickness like reaction) |

| Type IV, delayed | T lymphocytes | ||||

| IVa | Th-1 | Cell-mediated immunity, monocytes, macrophages, IFN-γ | Contact dermatitis | A few days to weeks after exposure‡ | Neomycin |

| IVb | Th-2 | Eosinophilic inflammation, IL-4, I L- 5 | DRESS | 2–6 weeks after exposure‡ | Nevirapine, vancomycin, sulfa antimicrobials, dapsone |

| IVc | CTL | CD4/CD8+ T cells, perforin, granzymes | SJS/TEN | 4 days to 1 month after exposure‡ | Nevirapine, sulfa antimicrobials, β-lactams |

| IVd | T lymphocytes | Neutrophils, IL-8 | AGEP | Within 1 week of exposure‡ | Aminopenicillins, pristinamycin, hydroxychloroquine, sulfa antimicrobials, fluoroquinolones, terbinafine |

Shorter duration of onset with pre-formed antibodies.

Shorter duration of onset with pre-sensitized T cells.

AGEP: Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis; CTL: Cytotoxic T-lymphocytes; DRESS: Drug rash, eosinophilia and systemic symptoms; Ig: Immunoglobulin; SJS: Stevens–Johnson syndrome; TEN: Toxic epidermal necrolysis; Th: T helper.

Pharmacogenomics of antimicrobial agents have helped to define the pathophysiology of antimicrobial treatment response and toxicity, but full translation into clinical practice has not been realized. There are examples of antimicrobial drugs that have either not been further developed or withdrawn from the market due to severe toxicities. Preclinical prediction of such toxicity and pharmacogenomic variation would ultimately result in more efficient drug discovery and design, and safer and more efficacious therapies. This manuscript reviews advances in antimicrobial pharmacogenomics with emphasis on genetic factors that affect antimicrobial PK/PD, efficacy and toxicity. Microbe virulence/resistance factors and host immune responses are also important in understanding variable responses to infectious diseases (Figure 1), but are beyond the scope of this review.

Overview

Key genes that have been associated with variation in efficacy and toxicity of various antimicrobial classes/agents are summarized in Tables 3–5. The more recent and significant findings are discussed in detail below.

Table 3.

Genetic associations (excluding HLA) with antimicrobial agent pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics.

| Genes | Allele | Phenotype | Drugs | Phenotypic associations | Level of evidence† | Selected references |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYP1A1 | rs1048943, 2454A>G with rs4646903, 3798T>C (e.g., *2B) | EM | Amodiaquine | Neutropenia with CYP1A1 EM genotypes | 4 | [14,15] |

| rs1048943, 2454A>G (e.g., *2C) | EM | |||||

|

| ||||||

| CYP1B1 | Reference (*1) | EM | Amodiaquine | Neutropenia with CYP1B1 EM genotypes | 4 | [15] |

| rs10012, 142C>G with rs1056827, 355G>T (e.g., *2) | EM | |||||

| rs10012, 142C>G, rs1056827, 355G>T with rs1056836, 4326C>G (e.g., *6) | SM | |||||

|

| ||||||

| CYP2A6 | rs1801272, 1799T>A (e.g., *2) | SM | Artesunate | Increased treatment failure with CYP2A6 SM or null genotypes | 4 | [16–18] |

| rs5031016, 6558T>C (e.g., *7) | SM | Possible contribution to apparent ‘artemisinin resistance’ in southeast Asia with CYP2A6 SM genotypes | NA | [19,20] | ||

| rs28399433,-48T>G (e.g., *9) | SM | Efavirenz | Increased plasma exposure with CYP2A6 SM genotypes | 1b | [21–23] | |

| rs28399454, 5065G>A (e.g., *17) | SM | |||||

| *4A to *4H | Null | |||||

|

| ||||||

| CYP2B6 | rs3745274, 516G>T (e.g., *6) | SM | Efavirenz | Increased plasma exposure with CYP2B6 SM genotypes | 1b | [24–32] |

| rs28399499, 983T>C (e.g., *18) | SM | Increased CNS side effects with CYP2B6 SM genotypes | 2b | [33–37] | ||

| rs4803419, 15582C>T (e.g., *1C) | SM | Nevirapine | Increased plasma exposure with CYP2B6 SM genotypes | 1b | [30,38–42] | |

| rs3745274, 516G>T (e.g., *6) | SM | Increased skin toxicity with CYP2B6 SM genotypes | 1b | [43] | ||

| rs28399499, 983T>C (e.g., *18) | SM | Artemisinins | Increased treatment failure with CYP2B6 SM genotypes (theoretical) | 4 | [17–18,44] | |

| rs4803419, 15582C>T (e.g., *1C) | SM | |||||

| rs3745274, 516G>T (e.g., *6) | SM | |||||

|

| ||||||

| CYP2C8 | rs11572103, 805A>T (e.g., *2) | SM | Chloroquine | Increased resistance with CYP2C8*2 and CYP2C8*3 | 3 | [45,46] |

| rs11572080, 416G>A and rs10509681, 1196A>G (e.g., *3) | SM | Amodiaquine | Increased resistance with CYP2C8*2 and CYP2C8*3 | 4 | [45,47,48] | |

| Hepatotoxicity and agranulocytosis with CYP2C8*2 and CYP2C8*3 | 4 | [14,17,47,48] | ||||

| Increased minor abdominal pain with CYP2C8*2 | 3 | [47] | ||||

|

| ||||||

| CYP2C19 | rs4244285, 681G>A (e.g., *2) | SM | Omeprazole and lansoprazole | Increased Helicobater pylori eradication with CYP2C19 SM genotypes | 2a | [49–51] |

| rs4986893, 626G>A (e.g., *3) | SM | Voriconazole | Increased plasma exposure with CYP2C19 SM genotypes | 1b | [52–56] | |

| rs17885098, 99C>T with rs3758581, 991A>G (e.g., *17) | UM | Increased visual side effects and hepatotoxicity with CYP2C19 SM genotypes | 3 | [52–57] | ||

| Etravirine | Increased plasma exposure with CYP2C19 SM genotypes | 3 | [58] | |||

| Nelfinavir | Increased plasma exposure with CYP2C19 SM genotypes | 1b | [27] | |||

| Biguanides | Increased plasma exposure with CYP2C19 UM genotypes | 3 | [59] | |||

|

| ||||||

| CYP2E1 | Reference (*1A) | EM | Isoniazid | Increased hepatotoxicity with CYP2E1*1A/*1A genotype | 2b | [60,61] |

| rs72559710, 1132G>A (e.g., *2) | SM | Increased hepatotoxicity with CYP2El*1A–*6–*1D haplotype | 3 | [62,63] | ||

| rs3813867, -1293G>C, rs2031920, -1053C>T with 7632T>A (e.g., *5A) rs3813867, -1293G>C and rs2031920, -1053C>T (e.g., *5B) 7632T>A (e.g., *6) |

||||||

|

| ||||||

| NAT1 | (*10) | FA | Sulfamethoxazole | Decreased hypersensitivity reactions in HIV-infected patients with NAT1 FA genotypes | 3 | [64] |

| *11 | FA | |||||

|

| ||||||

| NAT2 | *4 | FA | Isoniazid | Increased hepatotoxicity with NAT2 SA genotypes | 2b | [60,65–70] |

| *5 | SA | Increased tuberculosis treatment failure with NAT2 FA genotypes | 2b | [65] | ||

| *6 | SA | Sulfamethoxazole | Increased hypersensitivity reactions in HIV-infected patients with NAT2 SA genotypes | 3 | [71] | |

| *7 | SA | |||||

| *12 | SA | |||||

| *13 | SA | |||||

|

| ||||||

| GSTM1 | *0 | Null | Isoniazid | Increased hepatotoxicity with GSTM1 null genotype | 2b | [60,62,72] |

|

| ||||||

| GCLC | rs761142T>G | Sulfamethoxazole | Increased hypersensitivity in HIV-infected patients with rs761142T>G allele | 3 | [73] | |

|

| ||||||

| UGT1A1 | *28, rs887829 | – | Atazanavir | Increased unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia with UGT1A1 SM genotypes | 1b | [74,75] |

| Increased drug discontinuation UGT1A1 SM genotypes | 2b | [76,77] | ||||

| Indinavir | Increased unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia with UGT1A1 SM genotypes | 1b | [78] | |||

|

| ||||||

| G6PD | Deficiency | Dapsone | Increased hemolytic anemia | 1b | [79] | |

| Primaquine | Increased hemolytic anemia | 1b | [79] | |||

|

| ||||||

| ABCB1 | 3435C>T and others | Many | Associations reported but none consistently replicated | 2b | [52,80,81] | |

|

| ||||||

| OAT1, 0AT3, ABCC2, ABCC4 | Tenofovir | Increased renal tubulopathy | 2b | [82–91] | ||

|

| ||||||

| IL28B | rs12979860C>T | Pegylated interferon | Increased hepatitis C virologic response with rs12979860 CC genotype, rs8099917 TT genotype | 1a | [92–95] | |

| rs8099917T>G | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| ITPA | rs1127354A | Ribavirin | Decreased anemia with hepatitis C treatment with rs1127354 A and rs7270101 C genotypes | 1b | [96–101] | |

| rs7270101 C | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| PDE6 | Voriconazole | Increased visual side effects | 4 | [52] | ||

Levels of evidence (PharmGKB [102]): Level 1a = Annotation for a variant-drug combination in a Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) or medical society-endorsed pharmacogenomics guideline, or implemented at a Pharmacogenomics Research Network (PGRN) site, or in another major health system; Level 1b = Annotation for a variant-drug combination in which the preponderance of evidence shows an association. This association must be replicated in more than one cohort with significant p-values and preferably with a strong effect size; Level 2a = Annotation for a variant-drug combination that qualifies for level 2b, in which the variant is within a Very Important Pharmacogene (VIP) as defined by PharmGKB where their functional significance is more likely known; Level 2b = Annotation for a variant-drug combination with moderate evidence of an association. This association must be replicated, but there may be some studies that do not show statistical significance, and/or the effect size may be small; Level 3 = Annotation for a variant-drug combination based on a single significant (not yet replicated) study or annotation for a variant–drug combination evaluated in multiple studies but lacking clear evidence of an association; Level 4 = Annotation based on a case report, nonsignificant study, in vitro, molecular or functional assay evidence only EM: Extensive metabolizer; FA: Fast acetylator; NA: Not applicable; SA: Slow acetylator; SM: Slow metabolizer; UM: Ultrarapid metabolizer.

Table 5.

Mitochondrial DNA polymorphism associations with antimicrobial toxicities.

| Mitochondrial gene mutations | Population studied | Associated phenotypes† | Level of Evidence‡ | Selected references |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12sRNA mutations: 1555A>G, 1494C>T, 1095T>C, ET961Cn, 961T> G, 961T> C | Various (note: prevalence of 1555A>G mutation in the white population is 1 in 500) | Aminoglycoside ototoxicity | 1b | [124–127] |

|

| ||||

| 16s rRNA mutation: A2706G | Case report | Lactic acidosis with linezolid | 3 | [128] |

|

| ||||

| Haplogroups | ||||

| L1 c | Non-Hispanic black North American | Peripheral neuropathy | 3 | [129,130] |

| L3e1 | Black South African | Hypertriglyceridemia | 3 | [131] |

| L0a2, L2a | African (Malawian) | Peripheral neuropathy | 3 | [132] |

| W, I, T, H, K | European (Italians) and/or non-Hispanic white North American | Lipoatrophy/ lipodystrophy | 3 | [133–135] |

| H, clade HV, U | European (Spanish) and/or non-Hispanic white North American | Insulin resistance | 3 | [136,137] |

| I | European and/or non-Hispanic white North American | Dyslipidemia | 3 | [134] |

| Clade JT, T, H, clade HV | European (Spanish) | Atherogenic risk | 3 | [136] |

| T | Non-Hispanic white North American | Peripheral neuropathy | 3 | [138,139] |

| J, H3, U5a | Non-Hispanic white North American | Neuroretinal disorders | 3 | [140] |

Associated phenotypes with antiretroviral therapy for haplogroups.

Levels of evidence (PharmGKB [102]): Level 1a = Annotation for a variant-drug combination in a Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) or medical society-endorsed pharmacogenomics guideline, or implemented at a Pharmacogenomics Research Network (PGRN) site, or in another major health system; Level 1b = Annotation for a variant-drug combination in which the preponderance of evidence shows an association. This association must be replicated in more than one cohort with significant p-values and preferably with a strong effect size; Level 2a = Annotation for a variant-drug combination that qualifies for level 2b, in which the variant is within a Very Important Pharmacogene (VIP) as defined by PharmGKB where their functional significance is more likely known; Level 2b = Annotation for a variant–drug combination with moderate evidence of an association. This association must be replicated, but there may be some studies that do not show statistical significance, and/or the effect size may be small; Level 3 = Annotation for a variant–drug combination based on a single significant (not yet replicated) study or annotation for a variant–drug combination evaluated in multiple studies but lacking clear evidence of an association; Level 4 = Annotation based on a case report, nonsignificant study, in vitro, molecular or functional assay evidence only.

Antibacterial agents

Amoxicillin-clavulanate hepatotoxicity

Amoxicillin-clavulanate (AC) drug-induced liver injury (DILI) represents approximately 14% of all DILI cases [141] and is thought to be mainly due to the clavulanate component [142]. This affects approximately 1 in 1000 to 1 in 10,000 patients treated with AC [103]. Manifestations are heterogeneous, with a predominantly cholestatic pattern in up to 47% of cases but hepatocellular and mixed patterns are also common [104,143]. Fulminant hepatic failure requiring transplantation is rare, and biochemical abnormalities usually resolve without long-term consequences. The mean age of onset for AC-DILI is between 55 and 65 years [104,105,143], with mean time to onset 2 weeks after initiation of treatment [104–106,143].

Mechanisms underlying AC-DILI are unclear although immunologic reactions due to drug hapten presentation via MHC molecules have been proposed [103]. Early studies in Europeans showed associations between HLA-DRB1*15:01–DQB1*06:02 haplotype and increased risk of AC-DILI [103,105,106]. This finding was further supported by a recent genome-wide analysis study in individuals of Europeans descent that showed a strong association between AC-DILI and MHC class II SNP rs9274407, which correlated with rs3135388, a tag SNP of HLA-DRB1*15:01–DQB1*06:02 (p = 4.8 × 10-14) [104]. Individuals with homozygous alleles for this haplotype may be at even higher risk (odds ratio [OR]: 35.54; relative risk [RR]: 8.68; p < 1 × 10-8) [106]. Independent associations were also observed for the MHC class I region, rs2523822, which correlated to HLA-A*02:01 (p = 1.8 × 10-10) [104]. However, considering the population frequency of the HLA-DRB1*15:01–DQB1*06:02 haplotype in northern Europeans and the relatively infrequent occurrence of AC-DILI, MHC associations are likely not the only factors responsible for this condition [106]. Interestingly, as opposed to cholestatic AC-DILI in northern Europeans, a recent Spanish study found that a hepatocellular pattern of AC-DILI predominated in southern Europeans, with statistically significant associations with MHC class I alleles HLA-A*30:02 and HLA-B*18:01 (OR: 6.7 and 2.9, respectively) [107]. These patients with hepatocellular injury were younger (mean age 54 years) and more likely to be males. Other data suggest that HLA-DRB1*07 may be protective [105].

Flucloxacillin hepatotoxicity

The anti-staphylococcal β-lactam flucloxacillin is primarily associated with cholestatic hepatitis. Flucloxacillin DILI is rare (approximately 8.5 per 100,000) with onset between 1 to 45 days after initiation of therapy [144]. The DILIGEN study examined genome-wide associations in 51 cases of flucloxacillin DILI and 282 matched controls, and found the strongest association in the MHC region for rs2395029, corresponding to HLA-B*57:01 (p = 8.7 × 10-33) [110]. Further analysis of flucloxacillin DILI cases and flucloxacillin-tolerant controls showed that HLA-B*57:01 (rs2395029) was associated with an 80-fold increased risk for DILI (OR: 80.6; 95% CI: 22.8–284.9) [110].

The immunologic basis for HLA-B*57:01 restricted activation of flucloxacillin-specific cytotoxic CD8+ T-cell clones has also been demonstrated ex vivo, with activation occurring in a labile pharmacological interaction (p-i) manner [145,146]. Similar to amoxicillin-clavulanate, very few patients who carry the implicated allele or allele pairing develop hepatitis. Therefore, routine HLA-B*57:01 genotyping before prescribing flucloxacillin is currently not feasible as screening of almost 14,000 individuals would be required to prevent one case [268]. However, HLA-B*57:01 genotyping may be used to implicate flucloxacillin as the cause of severe cholestasis when other causes are possible [147].

Proton pump inhibitors & Helicobacter pylori eradication

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are combined with anti-bacterials to treat H. pylori-induced gastritis and peptic ulcer disease. They inhibit gastric acid secretion and raise intragastric pH, which makes H. pylori more susceptible to antimicrobial effects [148]. However, >20% of patients fail eradication therapy [149], likely owing to a combination of antimicrobial resistance and host factors.

All PPIs are extensively metabolized by CYP2C19 and CYP3A4, except for rabeprazole, which primarily undergoes nonenzymatic metabolism [150]. Plasma exposure differs between PPIs owing to different rates of CYP2C19 autoinhibition by metabolites. For example, omeprazole and esomeprazole metabolism by CYP2C19 produces sulfones, which in turn strongly inhibit CYP2C19, leading to nonlinear increases in area under the curve (AUC) with repeated administration [151]. CYP2C19 polymorphisms that define genotypes/phenotypes are provided in Table 3 [152–154]. Intermediate metabolizer phenotypes are heterozygous for rapid and poor metabolizer alleles.

Recent meta-analyses suggest an effect of CYP2C19 genotype on H. pylori eradication rates, particularly with omeprazole, but inconsistently with lansoprazole. Genotype status likely has no significant influence on eradication rates with rabeprazole and esomeprazole [49–51]. However, the choice of PPI and dosing strategy (twice daily versus once daily) may be important in overcoming the effect of CYP2C19 genotype [51].

Aminoglycoside otoxicity

All aminoglycosides can cause ototoxicity with bilateral high frequency sensorineural hearing loss, especially with prolonged treatment [124,125,155–157]. Several mitochondrial 12sRNA mutations (Table 5) have been associated with aminoglycoside-induced sensorineural deafness, especially a nucleotide A-to-G transition at position 1555 (1555A>G), although other factors such as cumulative dose and duration of therapy contribute [125,126,157]. In clinical practice, predisposing mitochondrial mutations are not routinely screened for before prolonged prescribing of aminoglycosides (e.g., for treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis). However, a family history of hearing loss should be elicited and aminoglycosides used with caution in those with a positive history.

Linezolid toxicity

Linezolid, an oxazolidinone antimicrobial used to treat multiresistant Gram-positive infections, binds to the 23S ribosome and prevents 30S–50S fusion in bacteria. There is evidence that major toxicities with linezolid, including optic and peripheral neuropathies, myelosuppression and hyperlactatemia, are mediated through inhibition of mitochondrial protein synthesis and hence mitochondrial mutations may play a role in genetic predisposition to these toxicities [158–162].

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole hypersensitivity in HIV patients

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) has been associated with hypersensitivity reactions of varying severity including generalized exanthem, drug reaction with eosinophilia, and systemic symptoms (DRESS)/drug-induced hypersensitivity reaction (DIHS) and Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS)/toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). Mild to moderate rash has been reported to affect up to 34% of HIV-infected patients with active HIV viremia [163]. Patients with HIV infection who develop TMP-SMX hypersensitivity in the setting of acute Pneumocystis jiroveci treatment and uncontrolled HIV-1 viremia will commonly tolerate TMP-SMX at lower prophylactic doses, and with subsequently suppressed HIV-1 replication on antiretroviral treatment, suggesting a role of immune activation. Although nearly 60% of HIV-infected patients who experienced mild to moderate reactions to TMP-SMX will tolerate the drug upon reintroduction [164], a Cochrane review showed that desensitization may result in fewer TMP-SMX discontinuations and side effects [165].

SMX is metabolized by both NAT1 and NAT2, and hypersensitivity reactions are thought to result from the formation of reactive hydroxylamine and nitroso metabolites [166]. NAT2 slow acetylator genotype status (Table 3) was found at a higher frequency in HIV-positive patients with hypersensitivity to SMX than HIV-positive controls without such reaction (74 vs 56%; adjusted p = 0.0003; OR: 2.3) [71]. Interestingly, HIV-infected patients with NAT2 slow acetylator genotypes may be protected from SMX hypersensitivity reactions by having concurrent gain of function mutations in NAT1 (carrying *10 and *11 alleles; OR: 0.28; 95% CI: 0.081–0.978; p = 0.046) [64].

A study of 14 candidate genes in HIV-infected patients with SMX hypersensitivity (102 cases vs 318 controls) also found significant association with SNP rs76114 2T>G in GCLC (adjusted p = 0.045) [73]. Heterozygous (TG) and homozygous (GG) are at increased risk compared with TT genotype (OR: 2.2 and 3.3, respectively). GCLC is part of GCL, a rate-limiting enzyme for formation of glutathione, a key enzyme in phase II conjugation of toxic metabolites. However, no associations have been found for HLA-DR, TNF, LTA and HSP1AL gene polymorphisms with TMP/SMX hypersensitivity [167]. A more recent study proposes that SMX elucidates select immune responses through its binding and alteration of critical residues in the CDR2β loop of a T-cell receptor that contains the domain Vβ20-1, which was sequenced from SMX responsive T-cells from patients with hypersensitivity reactions [168].

Dapsone hypersensitivity syndrome

Dapsone has proven efficacy in the treatment of leprosy, and is used in prophylaxis for malaria and P. jiroveci infection among HIV-infected patients. Although combined formulation with chlorproguanil (Lapdap) was effective for treating uncomplicated falciparum malaria [169], it was withdrawn from the market in 2008 owing to risk of severe hemolysis in patients with G6PD deficiency, particularly with dapsone [170–172].

Dapsone hypersensitivity syndrome (DHS) is commonly reported among Asians. Patients with DHS often present with fever, lymphadenopathy, generalized rash and hepatitis [173]. It occurs at a mean duration of 28 days after administration and mortality can be up to 10% [173]. HLA-B*13:01 was confirmed as a risk factor for DHS in a recent genome-wide study involving 872 Han Chinese patients treated for leprosy (39 DHS vs 833 controls; OR: 20.53; p = 6.84 × 10-25; localizing to SNP rs2844573) [108].

Antituberculous drugs

Isoniazid (INH), rifampicin, pyrazinamide and ethambutol remain the mainstay of treatment for drug-sensitive tuberculosis. However, of all the antituberculous drugs, only isoniazid pharmacogenomics have been extensively studied [60–63,65 – 67,72,174–182].

INH hepatotoxicity

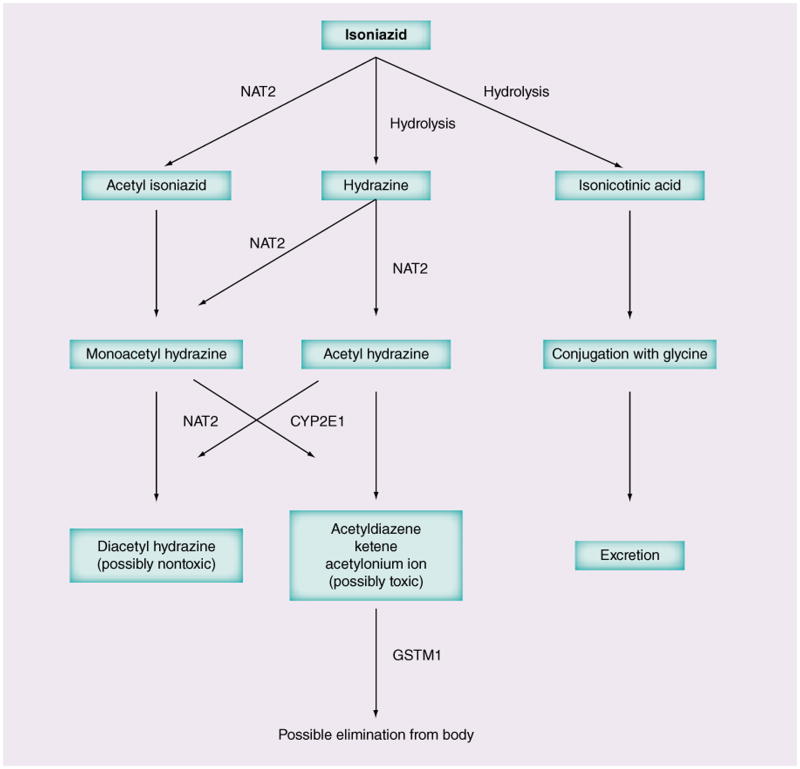

INH can cause hepatotoxicity in 1–30% of patients and this risk increases with coadministration of rifampin [62,183]. INH DILI manifests within 3 months of drug administration and can present with gastrointestinal symptoms, transaminitis, cholestasis or even isolated jaundice in some cases. Mortality may reach 10% [62]. NAT2, CYP2E1, GSTM1 and GSTT1 are the extensively studied enzymes in INH DILI (see Figure 2 for INH metabolism).

Figure 2. Isoniazid metabolic pathways.

GST: Gluthathione-S-transferase; NAT: N-acetyl transferase.

NAT2

Several studies have examined the associations between genetic polymorphisms in NAT2 and the risk of hepatotoxicity across different ethnicities [60,62,65–67,174,176]. NAT2 polymorphisms that define its phenotypic acetylator status are shown in Table 3 [62,174]. Intermediate acetylators carry one fast and one slow acetylator allele. Three recent meta-analyses, which included different ethnic populations showed that slow acetylator genotypes were significantly associated with hepatotoxicity (range of OR: 1.93–4.69) [60,66,67], although the meta-analysis by Wang et al. showed no difference in DILI rates between intermediate and rapid acetylators [67]. Subgroup analyses further demonstrated that this risk extended to all ethnic groups except Caucasians, who were under-represented [60]. A study of efavirenz and rifampin-based regimens in an Ethiopian population coinfected with HIV and TB (41 cases vs 160 controls) also showed increased risk of DILI with slow acetylator genotypes (p = 0.039), possibly resulting from three-way interactions between INH, rifampin and efavirenz [183].

A randomized, controlled trial involving 172 Japanese patients with tuberculosis compared the outcomes of pharmacogenomics-guided INH dosing regimens (2.5 mg/kg for slow acetylators, 5 mg/kg for intermediate acetylators and 7.5 mg/kg for fast acetylators) to a standard treatment regimen (5 mg/kg). This study found that pharmacogenomics-guided INH dosing was associated with lower treatment failure rates in rapid acetylators receiving higher doses (15 vs 38%; RR: 0.379; 0.097–0.776; p = 0.015) and lower risk of hepatotoxicity in slow acetylators receiving lower doses (0 vs 78%; RR: 4.5; 95% CI: 1.3–1.53) [65].

Others

Table 3 summarizes other important genetic associations with INH DILI. The evidence for CYP2E1 polymorphisms has been conflicting [60, 62,174,177,184]. While some studies, including a meta-analysis, showed that *1A/*1A genotype was associated with increased risk of INH DILI, particularly in combination with NAT2 slow acetylator status [61,66,177], other studies have not replicated the same findings [176,178], or significant association was found only in east Asians [60]. Variant CYP2E1*6 allele and *1A–*6 –*1D haplotype were also shown to be associated with increased risk of INH DILI [63] but CYP2E1*1C polymorphisms were not [179].

Associations between GSTM1 null genotype and INH DILI were also shown in a recent meta-analysis [60] but such associations may be ethnicity specific [60,63,72]. GSTT1 null genotype, on the other hand, was not associated with hepatotoxicity in different ethnic populations [60,62,175]. Other interesting associations with INH DILI include polymorphisms in minor variant allele A (AG or AA genotypes) of TNF-α gene in Korean patients [182], mitochondrial MnSOD 47T>C mutation in Taiwanese patients [72], absence of HLA-DQA1*01:02 and presence of HLA-DQB1*02:01 in Indian patients [181], and lack of association with genetic polymorphisms in CES1, 2 and 4 genes in Asians and Caucasians from Canada [180]. The relevance and practical applications of these findings remain uncertain.

INH peripheral neuropathy

Few studies have examined the risk of developing peripheral neuropathy with polymorphisms in enzymes involved in INH metabolism. Previous small studies showed that NAT2 slow acetylators seemed to be at higher risk [62,68,69]. Genotyping of sural nerve biopsy samples in five Japanese patients with INH neuropathy found NAT2 slow acetylator genotype status in all five, although no controls were included [70].

Antifungal agents

Voriconazole

Voriconazole undergoes elimination primarily by CYP2C19 (Table 3) and plasma voriconazole levels were found to be three-times higher in CYP2C19 poor metabolizers and two-times higher in intermediate metabolizers compared with rapid metabolizers [52,185,186]. More recently younger age and gain-of-function alleles (CYP2C19*17) have been associated with subtherapeutic voriconazole concentrations suggesting higher dose requirements in some populations [187]. In those who lack CYP2C19 activity, secondary metabolism by CYP3A4 may become more important. Although CYP3A4 polymorphisms do not influence voriconazole metabolism, coadministration with medications that inhibit CYP3A4 may lead to increased risk of toxicity [185,186]. Efflux pumps (MDR1/P-gp polymorphisms such as 3435C>T) may also play important roles in voriconazole elimination [52,186].

Hepatotoxicity is a complication of voriconazole treatment, possibly related to high trough plasma concentrations [188]. However, very little clinical pharmacogenomics data exist for correlations between CYP2C19 genotypes and phenotypic manifestations of hepatotoxicity. A study by Levin et al. and also another small Japanese study of 29 patients found that hepatotoxicity (predominantly cholestasis followed by hepatitis patterns) was associated with high trough voriconazole concentrations but no discernible CYP2C19 genotype association was noted [53,54]. Nevertheless, the latter study proposed pharmacogenomics guided initial dosing of voriconazole to attain favorable PK parameters [54]. A more recent study by Zonio et al. also found that genotypes did not influence voriconazole or metabolite levels, and hence toxicity significantly [57].

In addition, CYP2C19 genotypes and polymorphisms in the PDE6 enzyme have been implicated in the development of visual side effects with voriconazole, although further studies are needed in this area [55,189].

Antimalarial agents

Malaria remains a major cause of mortality in many regions of the world. The WHO recommends four different artemisinin combination therapies for treatment of uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum infection in adults (Table 6) [190], while primaquine remains the primary agent for eradicating intrahepatic hypnozoites of Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium ovale. Major metabolic pathways for antimalarial agents include CYP2A6 for artesunate, CYP2B6 and CYP3A4 for other artemisinins, CYP2C8, CYP1A1 and CYP1B1 for amodiaquine, and CYP2C19 for biguanides [16]. However, pharmacogenomic associations with many antimalarial agents remain theoretical owing to lack of clinical studies in resource-limited settings.

Table 6.

WHO recommended options for artemisinin combination therapy for treatment of Plasmodium falciparum malaria.

| Regimen | Artemisinin | Partner long-acting drug |

|---|---|---|

| AL | Artemether | Lumefantrine |

| AS+AQ | Artesunate | Amodiaquine |

| AS+MQ | Artesunate | Mefloquine |

| AS+SP | Artesunate | Sulfadoxine and pyrimethamine |

AL: Artemether and lumefantrine; AS: Artemisinins; AQ: Amodiaquine; MQ: Mefloquine; SP: Sulfadoxine and pyrimethamine Data taken from [190].

Artemisinins

CYP2A6 plays a major role in metabolizing artesunate to its active anabolite, dihydroartemisinin [16,17], while CYP2B6, CYP1A1 and CYP1A2 play minor roles [19]. Compared to the reference CYP2A6*1A allele, approximately 40 gene variants exist, of which at least 13 demonstrate decreased metabolism and three no activity in vivo (selected genotypes are listed in Table 3) [191,192]. Variants with little or no enzyme activity may result in artesunate treatment failure and may contribute to emerging artemisinin resistance in Thailand. Clinical studies that correlate CYP2A6 genotype with artemisinin combination therapy outcomes are needed [18–20]. An impact of CYP2B6 polymorphisms on artemisinins metabolism remains theoretical, and was not shown in a study involving Cambodians and Tanzanians [44].

Amodiaquine

CYP2C8 converts amodiaquine (AQ) to the non-toxic moiety N-desethylamodiaquine. Quinoneimines (QNMs) are toxic metabolites more likely to be formed from AQ in the setting of CYP2C8 slow metabolizer genotypes [17]. QNMs cause agranulocytosis and severe liver damage at an incidence of 1:2000 [14]. In vivo studies have shown that extrahepatic metabolism by CYP1A1 and CYP1B1 may also generate QNMs, further contributing to agranulocytosis [14,17]. The impact of CYP2C8 polymorphisms on AQ efficacy and safety warrants further study [15,47,48].

Mefloquine

Mefloquine has a long elimination half-life (15–25 days) and is metabolized to inactive compounds by CYP3A4 [193]. Limited data suggest that P-gp/ABCB1 polymorphisms (1236, 2777, 3435 CC, CG or GG > TT genotypes; OR: 6.3, 10.5 and 5.4, respectively) and 1236–2777–3435TTT haplotype (p = 0.004) are associated with neuropsychiatric side effects, particularly in white females [80,81]. Reduced efflux of mefloquine in neural tissues as a result of transporter polymorphisms may explain this association [16].

Biguanides

The biguanides, proguanil and chlorproguanil, are converted into active antimalarial metabolites, cycloguanil and procycloguanil, by CYP2C19 and less so by CYP3A4 [17]. A study in Gambian adults with uncomplicated malaria showed that ultrarapid metabolizers (CYP2C19*17 homozygotes) had higher AUC and Cmax values for these active metabolites [59]. However, other studies showed no association between CYP2C19 polymorphisms and breakthrough parasitemia, treatment failure, ex vivo antimalarial activity or mild adverse events, possible reflecting compensatory metabolism by CYP3A4 (reviewed in [17]).

Other antimalarial agents

Primaquine-induced hemolysis has long been associated with G6PD deficiency, which is common in sub-Saharan Africans (∼10–25%) [79]. Other potential associations include P-gp/ABCB1 polymorphisms with quinine neurotoxicity, OCT-2-related pancreatic insulin secretion in quinine-induced hypoglycemia, CYP3A5*3/*3 genotype with quinine hydroxylation, and ABC transporter polymorphisms with chloroquine neurotoxicity [16,17]. Pharmacogenomics of lumefantrine and newer agents such as tafenoquine, pyronaridine and piperaquine warrant further study.

Antiviral agents

Hepatitis C antivirals

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) affects more than 150 million people worldwide and causes more than 350,000 deaths annually from HCV-related liver disease. The established standard of HCV treatment had been peg-IFN and ribavirin (RBV) combination therapy although contemporary treatment is now moving towards combination therapy with direct acting agents (DAA) and it is likely that in the near future combination DAA regimens that spare both peg-IFN and RBV will be the standard of care. Peg-IFN/RBV regimens are lengthy (24–72 weeks), poorly tolerated and have low response rates in HIV coinfected patients, particularly with HCV genotype 1 disease. Newer direct acting antiviral agents such as the NS3/4A protease inhibitors boceprevir and telaprevir have been added to peg-IFN/RBV as triple therapy for the chronic HCV monoinfection with markedly improved efficacy, and data from HIV/HCV coinfected patients are extremely encouraging.

In large gemome-wide association studies, genetic polymorphisms in the IL28B gene (rs12979860 and rs8099917), which encodes IL28B, a IFN-λ3, have been strongly associated with response to IFN-based HCV genotype 1 therapy, and spontaneous clearance of HCV [92–94] (Table 3). Neither SNP is in a coding region and it is thought that IL28B rs12979860CC and rs8099917TT genotypes are associated with low expression of IFN-stimulated genes, which leads to greater induction of these genes with IFN exposure and better treatment response. A functional variant TT/-G polymorphism in the CpG island upstream of IL28B has been shown to induce IL28B and IP-10 and may better predict HCV clearance than rs12979860 [95]. African–Americans are less likely to have favorable IL28 genotypes, which may contribute to their lower response rates to treatment. IL28B genotyping may be less predictive in HCV genotype 2 and 3 infections where treatment response rates are much higher than with HCV genotype 1.

For liver transplant patients reinfected with HCV genotype 1, studies have also associated sustained virologic response (SVR) and IL28B genotype of both the donor and recipient [194–196]. Emerging data in patients co-infected with HCV (genotype 1 and 4) and HIV-1 have also associated SVR with peg-IFN/ RBV with IL28B genotype, including previous non-responders to peg-IFN/RBV [197]. An additional study in Europeans with HCV genotype 1, and reproduced by a Japanese group, found that an unfavorable C2/C2 HLA-C genotype in combination with the two IL28B SNPs rs8099917 and rs12979860 increased the positive predictive value of nonresponse from 66 to 80% [198,199]. A dinucleotide frameshift variant in rs368234815 (TT or ΔG) has been described, which generated IFNL4, and is in high linkage disquilibrium with rs12979860. The IFN-γ gene is largely inactive in human populations due to a frameshift mutation. It represents a paradox by which it exerts antiviral activity yet rs368234815 (ΔG) allele carriers have impaired clearance of HCV and decreased response to HCV treatment [200–203]. Currently DAAs are extremely expensive and drug interactions with HCV/HIV coinfected patients are complex. Triple therapy of IFN/ RBV with DAAs has been shown to significantly improve the response in nonresponder genotypes. In addition, however, there is evidence that patients with favorable IL-28B genotypes continue to have better efficacy and HCV virologic control even in IFN/RBV regimens in combination with DAAs and possibly IFN-free regimens, suggesting that IL28B genotype itself may impact viral kinetics [204].

Anemia has been reported in 30–50% of treatmentnaive patients receiving IFN/RBV treatment, with higher rates reported in combination with telaprevir and boceprevir. RBV-associated hemolysis is a major cause of anemia, which is more common in females, older patients, with higher RBV dose and lower baseline hemoglobin. Two variants in the ITPA gene (rs1127354 and rs7270101) have been associated with protection against anemia in patients receiving IFN/RBV [96–101]. These minor variant alleles were protective against anemia in patients with HCV genotype 2 and 3 and HIV/HCV coinfection treated with IFN/RBV. Similar protective effects were seen in HCV mono-infected patients treated with telaprevir/pegIFN/RBV. Prospective ITPA genotyping is not currently recommended, but could in the future be used with other PK and pharmacogenomic information to guide therapy.

Currently there are no definitive recommendations for IL28B genotyping prior to HCV treatment. IL28B genotype is currently the strongest available baseline predictor of HCV treatment response for IFN/RBV-containing regimens; however, it is not the only factor for consideration in treating the individual patient [205]. The greatest utility in an era when IFN-based regimens are still used would be to predict likelihood of SVR, which could lead to shortened treatment duration in patients predicted to have a favorable treatment response, or conversely to define which patients should initiate triple therapy, in HCV genotype 1 patients and HIV/HCV coinfected patients with genotype 1 or 4. Given the high efficacy of new direct acting anti-HCV agents, with rapid movement toward IFN-sparing and RBV-sparing HCV treatment, the above issues may become less relevant over time.

Antiretroviral drugs

Over 25 antiretrovirals have been US FDA approved for combination antiretroviral therapy (ART). In addition, there are four fixed-dose combinations that provide single-tablet once-daily regimens. Recent HIV clinical trials and guidelines have endorsed test and treat strategies, treatment as prevention, and early ART initiation in attempts to reduce transmission and long-term morbidity. With patients remaining on the same ART regimen for >15 years, it is increasingly important to individualize ART to maximize efficacy, effectiveness and safety.

Nucleoside/tide reverse transcriptase inhibitors

The major treatment limiting toxicity of the guanosine analog, abacavir, is drug hypersensitivity syndrome (ABC HSR) that affected 5–8% of participants in clinical trials, and was well characterized during premarketing drug development [111,206]. In 2002, two groups independently discovered an association between ABC HSR and the HLA class I allele HLA-B*57:01 [112,207,208]. Over the subsequent 6 years and through numerous translational hurdles, a randomized clinical trial confirmed the utility of HLA-B*57:01 testing to prevent immunologically mediated (defined by ABC patch testing) ABC HSR [209,210]. Keys to translating HLA-B*57:01 from discovery to guideline-supported implementation included the 100% negative-predictive value of HLA-B*57:01 for ABC HSR, generalizability of this high predictive value across ethnic groups, the low number of tests needed to test to prevent each ABC HSR case, and the development of cost effective and quality assured laboratory technologies [13,113,211].

Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate is the prodrug of the nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitor, tenofovir. As many as 2% of those on long-term tenofovir develop significant declines in creatinine clearance, which is more likely with lower bodyweight, advanced age, pre-existing renal dysfunction, medical comorbidities, advanced HIV disease and concurrent nephrotoxic medications. Tenofovir nephrotoxicity can also manifest as proximal tubular dysfunction without evidence of impaired creatinine clearance. The mechanism of tenofovir renal toxicity has been postulated to reflect direct effects on tubular function or mitochondrial toxicity similar to the related nucleotide analogs, adefovir and cidofovir. Tenofovir is transported into renal proximal tubular cells by organic anion transporters hOAT1 and OAT3, and secreted into the tubular lumen by MRP4. Therefore pharmacogenomic studies of tenofovir toxicity have focused on these influx and efflux drug transporter genes, with inconsistent results (Table 3). Larger studies with more standardized definitions of renal toxicity may clarify the pharmacogenomic basis of tenofovir nephrotoxicity, as well as drug–drug interactions with tenofovir [82–91,212,213]. Drug transporters are also relevant to pre-exposure prophylaxis, as tenofovir may preferentially concentrate in rectal tissue following oral dosing based on mucosal transporter expression [214]. The newer prodrug of tenofovir, tenofovir alafenamide, concentrates in peripheral blood mononuclear cells resulting in lower plasma exposures at one tenth of the dose and potentially less renal toxicity [215].

Thymidine analogs (zidovudine/stavudine) & ‘D drugs’

Many thymidine analog-associated toxicities reflect mitochondrial toxicity mediated through inhibition of host DNA polymerase-γ. This includes lipoatrophy [133–135,216–218], a largely irreversible mitochondrial toxicity associated with stavudine (d4T) more so than with zidovudine, peripheral and other neuropathies (associated with the ‘D drugs’ d4T, didanosine [ddI] and zalcitabine [ddC]) [129,132,138–140,219,220], lactic acidosis [221–228] and metabolic disease [131,134,136,137,229]. Pharmacogenomic associations with these phenotypes are summarized (Tabl e 5). Risk of lipoatrophy is associated with duration of treatment, female gender and lower body mass. Contemporary practice discourages the use of these agents, which has markedly reduced new cases, and WHO guidelines that currently recommend earlier initiation of ART exclude d4T from first-line therapy and suggest use of zidovudine only when tenofovir cannot be used. A recent study in d4T-treated patients from Malawi suggested that certain mtDNA haplogroups may protect against lipoatrophy [230].

Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors

The non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors efavirenz and nevirapine have been extensively prescribed for HIV-1 infection worldwide. Efavirenz is metabolized primarily by hepatic CYP2B6, with minor contributions by CYP2A6 and CYP3A4/5 [231,232], and direct N-glucuronidation by UGT2B7 [231,233]. At least three CYP2B6 loss-of-function polymorphisms have been consistently associated with increased plasma efavirenz exposure, 516G>T (rs3745274, CYP2B6*6, *7, *9 and *13) [24–29], 983T>C (rs28399499, CYP2B6*16 and *18) [29–32] and 15582C>T (rs4803419, CYP2B6*1C, *13B and * 15A) [29] (Table 3). Greater mean plasma efavirenz trough concentrations with African ancestry than with European ancestry are largely explained by differing frequencies of CYP2B6 516G>T. The effect of CYP2B6 983T>C on efavirenz concentrations (per C allele) is somewhat greater than that of 516G>T [29], but its frequency is far less and appears to be found only with African ancestry. The effect of CYP2B6 15582C>T (per allele) is less than that of 516G>T [29], but its frequency is high with European and Asian ancestry. These three polymorphisms stratify patients into ten plasma trough concentration subgroups across an approximately tenfold range of medians [29]. These polymorphisms explain approximately 35% of inter-individual variability in efavirenz trough concentrations [29]. The top three strata (CYP2B6 slow metabolizer genotypes) are defined by 516T/T homozygosity, dual 516G/T-983C/T heterozygosity and 983C/C homozygosity. With CYP2B6 slow metabolizer genotypes, even greater plasma efavirenz concentrations are associated with polymorphisms in minor pathway genes CYP2A6 (-48T>G, rs28399433) [21,22,234] and possibly UGT2B7 (homozygosity for 735A>G, rs28365062) [22,23].

While genetic predictors of increased plasma efavirenz exposure are well established, associations between plasma efavirenz concentrations and CNS side effects have been less consistent, reported in some studies [26,235–239] but not others [240–242]. Such inconsistency may relate to inconsistent definitions of CNS toxicity and attenuation of efavirenz CNS symptoms with repeated dosing [237]. In the only double-blinded, placebo-controlled study to specifically assess efavirenz CNS symptoms, efavirenz was significantly associated with increased CNS symptoms within the first week of treatment, but at week 4 and beyond CNS symptoms did not differ between efavirenz and placebo recipients [237].

Precision efavirenz dosing guided by genetic testing might decrease side effects and drug cost. With CYP2B6 intermediate or slow extensive metabolizer genotypes, efavirenz could likely decrease from the usual 600 mg daily dose to 400 mg in intermediate metabolizers, and 200 mg in slow metabolizers, without reducing virologic responses [243]. It is reassuring that the lowest CYP2B6 extensive metabolizer genotype stratum is not at increased risk for virologic failure with 600 mg once-daily efavirenz dosing [244]. By contrast, universal efavirenz dose reduction without genetic screening, as studied in ENCORE1 [245], might increase risk for virologic failure in the lowest CYP2B6 extensive metabolizer genotype stratum.

ADRs with nevirapine are primarily immune mediated, occur within the first 2 months of therapy, and affect the liver and/or skin. These include mild to moderate skin rash or, less commonly, severe cutaneous adverse reactions such as SJS/TEN or DRESS/DIHS. In a clinical trial from South Africa, in which participants with lower plasma HIV-1 RNA concentrations (i.e., higher CD4+ T-cell counts) were stratified to receive nevirapine-containing regimens, 17% of nevirapine recipients experienced grade 3 or 4 liver toxicity, and two died of hepatic failure [246]. Inactivation of nevirapine occurs primarily through hepatic CYP2B6, less so through CYP3A and other isoforms; nevirapine induces its own metabolism (i.e., autoinduction). As with efavirenz, increased plasma nevirapine exposure has been associated with CYP2B6 loss-of-function variants including 516G>T [26,38,39,247–249], 983T>C [40] and 15582C>T [39]. An association has been reported between nevirapine pharmacokinetics and rash, with 50% increased likelihood of rash for every 20% decrease in plasma nevirapine clearance [250].

Genetic variants that confer increased risk for nevirapine hepatic events differ for those associated with cutaneous events without liver involvement. A seminal study from western Australia implicated HLA-DRB1*01:01 (HLA class II) and CD4% ≥25 with rash-associated hepatic events in a largely Caucasian cohort [251]. A relationship was later reported between HLA-DRB1* 01:02 and nevirapine-associated hepatic events (rash status unknown) in a largely black African cohort [120]. By contrast, studies in Sardinia and Japan implicated HLA-Cw* 08 in hepatotoxicity [116,252]. Regarding nevirapine-associated cutaneous events, studies in Thailand implicated HLA-Cw*04:01 and HLA-B*35:05 (HLA class I) [115,121,253]. In a large, retrospective, case-controlled pharmacogenomic study that separately considered severe cutaneous and hepatic adverse events, and separately considered cohorts of Asian, European and African descent [122], cutaneous events were associated with HLA-Cw* 04, especially among black subjects and Asians, and with HLA-B*35 among Asians. The CYP2B6 loss-of-function variant 516G>T was also associated with cutaneous but not hepatic adverse events. Hepatic adverse events were associated with HLA-DRB1*01 among white subjects, but this allele was infrequent among black subjects and rare among Asians. More recently, SJS/TEN has been associated with HLA-C*04:01 in a Malawian cohort [123]. Although immune-mediated nevirapine ADRs cannot be reliably predicted by class I or class II HLA associations, implicated HLA alleles may share peptide binding characteristics [254]. The impact of CD4+ T-cell count is expected to be greater with HLA class II mediated hepatic events than HLA class I mediated cutaneous events. This is supported by in vitro studies showing that nevirapine-specific CD8+ T-cell responses and depletion of CD8+ T cells more markedly abrogate nevirapine-specific IFN-γ output than CD4+ T-cell depletion [117]. In addition, recent data suggest that high CD4%/count may not significantly increase risk of toxicity when virologically suppressed HIV-positive patients on combination antiretroviral therapy switch to nevirapine-based regimens [255–257]. Data are limited regarding pharmacogenetics of the newer non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, etravirine and rilpivirine. Loss-of-function CYP2C19 variants are associated with greater plasma etravirine exposure [58], but implications for etravirine prescribing are not known.

Protease inhibitors

Pharmacogenomics relationships have been proposed for many HIV-1 protease inhibitors, but results have been inconsistent and clear efficacy relationships have not been established (Table 3) [41,258–260]. CYP3A4 primarily metabolizes many HIV-1 protease inhibitors, and most also inhibit CYP3A. The potent CYP3A inhibitor ritonavir is frequently used as a PK enhancer to increase exposure of other CYP3A substrate protease inhibitors. Ritonavir and other protease inhibitors are also substrates for the efflux transporter P-gp, and for other drug transporters such as OATP1A2, OATP1B1 and OATP1B3, and somewhat higher lopinavir plasma exposure has been consistently associated with SCLCO1B1 521T>C [261,262]. Synthetic PK enhancers lacking antiretroviral activity such as cobicistat have been developed to boost elvitegravir (integrase inhibitor) and HIV protease inhibitors.

Protease inhibitors have been associated with metabolic disturbances, including ritonavir with hypertriglyceridemia. Genetic variants associated with hyperlipidemia in HIV-negative populations appear to be over-represented in patients with hyperlipidemia on protease inhibitor therapy (Table 5) [263,264].

Both atazanavir and indinavir inhibit plasma bilirubin clearance by competing for binding to UGT1A1, resulting in unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia. The magnitude of hyperbilirubinemia is associated with a promoter polymorphism in UGT1A1 (UGT1A1*28), that is significantly associated with reduced bilirubin-conjugating activity and unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia [74]. Approximately 6% of patients develop clinically apparent jaundice and studies have suggested a correlation between UGT1A1 polymorphisms and atazanavir treatment discontinuation [76]. Bilirubin uptake into hepatocytes is also facilitated by OATP1B1 and OATP1B3, and SLCO1B1 polymorphisms may contribute to unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia with atazanavir [265,266]. A recent genome-wide association study showed that atazanavir-associated hyperbilirubinemia was most strongly associated with UGT1A1 rs887829 (which is in almost complete linkage with UGT1A1*28), but with no polymorphisms beyond UGT1A1 [75].

Future perspective

Pharmacogenomic discoveries have contributed to understanding of pathogenesis of infections, host–pathogen interactions, and efficacy and toxicities of antimicrobial agents [3]. Translational successes such as HLA-B*57:01 screening to prevent ABC HSR, and IL28 genotyping prior to HCV treatment, provide encouragement that pharmacogenomics can improve safety, efficacy and effectiveness of antimicrobials. Other associations, such as HLA-B*13:01 screening in Han Chinese for dapsone hypersensitivity syndrome, may become standard of care as more data become available [65,108]. However, major challenges remain on many fronts, including for HIV, tuberculosis and malaria, where continued pharmacogenomic studies are warranted given the huge epidemiological burdens worldwide [17].

In the future, pharmacogenomic studies of well-phenotyped populations, coupled with newer quality-assured technologies such as high-throughput deep sequencing, will facilitate understanding of interactions between host, drug, and pathogen genetic signatures that are important in determining the pathogenesis, efficacy and toxicity of antimicrobial treatment. Research advances in type A and type B reactions will improve prediction of interactions between drugs and their targets, as well as predisposing MHC genotypes leading to more efficient drug design and development [47,203,204]. Pharmacogenomic-guided stratification and dosing has the potential to increase power and improve outcomes of clinical studies [267]. The field of pharmaco genomics will likely continue to evolve. For antimicrobial agents, this will have downstream benefits not only for improved understanding of immunopathogenesis of antimicrobial efficacy and toxicity and host–pathogen interactions, but also translation into safer, more efficacious and cost-effective applications.

Table 4.

MHC class I and II polymorphism associations with hypersensitivity reactions to antimicrobials.

| HLA associations | Population studied | Antimicrobial hypersensitivity | Level of Evidence† | Selected references |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HLA-DRB1*15:01– DQB1* 06:02 and HLA-A*02:01 | White Europeans and Americans | AC-DILI, predominant cholestatic/mixed pattern | 1b | [103–106] |

|

| ||||

| HLA-DRB1*07 and HLA-A1 | Northern Europeans | Protective from AC-DILI | 3 | [105] |

|

| ||||

| HLA-A*30:02 and HLA-B*18:01 | Spanish | AC-DILI, predominant hepatocellular injury | 3 | [107] |

|

| ||||

| HLA-B*13:01 | Han Chinese | Dapsone hypersensitivity syndrome | 1b | [108,109] |

|

| ||||

| HLA-B*57:01 | European | Flucloxacillin DILI | 1b | [110] |

| All races | Abacavir hypersensitivity syndrome | 1a | [111–113] | |

|

| ||||

| HLA-DRB1*01, HLA-DRB1*01:01 | Australian, European, white | Nevirapine hepatotoxicity phenotype (abrogated by low CD4 count for HLA-DRB1*01:01) | 1b | [43,114] |

|

| ||||

| HLA-DRB1*01: 02 | White, European South African | Nevirapine hepatotoxicity phenotype | 2b | [40,115] |

|

| ||||

| HLA-Cw*8 or HLA-Cw*8-B*14 haplotype | Italian, Japanese | Nevirapine DIHS/DRESS (cutaneous phenotype) | 2b | [43,116–119] |

|

| ||||

| HLA-Cw*4 | Han Chinese, white, black, southeast Asians | 1b | [77,115,120–122] | |

|

| ||||

| HLA-C*04:01 | White, southeast Asians | 2b | ||

|

| ||||

| HLA-B*35 | Southeast Asian, whites | 1b | ||

|

| ||||

| HLA-B*35:05 | Asian, southeast Asians | 1b | ||

|

| ||||

| HLA-B*35/Cw*4 | 2b | |||

|

| ||||

| HLA-B*35:01 | Australian | 2b | ||

|

| ||||

| HLA-C*04:01 | Malawians | Nevirapine SJS/TEN | 3 | [123] |

Levels of evidence (PharmGKB [102]): Level 1a = Annotation for a variant-drug combination in a Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) or medical society-endorsed pharmacogenomics guideline, or implemented at a Pharmacogenomics Research Network (PGRN) site, or in another major health system; Level 1b = Annotation for a variant-drug combination in which the preponderance of evidence shows an association. This association must be replicated in more than one cohort with significant p-values and preferably with a strong effect size; Level 2a = Annotation for a variant-drug combination that qualifies for level 2b, in which the variant is within a Very Important Pharmacogene (VIP) as defined by PharmGKB where their functional significance is more likely known; Level 2b = Annotation for a variant–drug combination with moderate evidence of an association. This association must be replicated, but there may be some studies that do not show statistical significance, and/or the effect size may be small; Level 3 = Annotation for a variant-drug combination based on a single significant (not yet replicated) study or annotation for a variant-drug combination evaluated in multiple studies but lacking clear evidence of an association; Level 4 = Annotation based on a case report, nonsignificant study, in vitro, molecular or functional assay evidence only.

AC: Amoxicillin-clavulanate; DIHS: Drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome; DILI: Drug-induced liver injury; DRESS: Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms; SJS: Stevens–Johnson syndrome; TEN: Toxic epidermal necrolysis.

Executive summary.

Pathogenesis of antimicrobial efficacy & toxicity, & pharmacogenomics associations

Efficacy of antimicrobial agents and their toxicities, both type A and/or type B reactions, are affected by pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) profiles of individual agents, which are in turn influenced by absorption, distribution, metabolism and elimination (ADME) enzymes, and by immunologic interactions between MHC peptides, drug molecules and T cells. Some toxicities result from mitochrondrial dysfunction.

Polymorphisms in ADME genes such as CYPs, N-acetyl transferases (NATs), gluthathione-S-transferase (GSTs), UDP-glucuronosyltransferases (UGTs), P-gp/multidrug resistance protein (MDRs) and organic anion transporters (OATs)/organic cation transporters (OCTs) may influence gene expression, further influencing the antimicrobial effectiveness or risk of toxicities (mainly type A reactions). Examples of implicated antimicrobials include antimalarial drugs, isoniazid, sulfamethoxazole, voriconazole, HIV agents (tenofovir, efavirenz and protease inhibitors), and proton pump inhibitors for Helicobacter pylori treatment.

Polymorphisms in HLA genes influence risk of type B hypersensitivity reactions. Multiple MHC class I genes have been implicated in high-risk associations. Associations include HLA-DRB1*15:01-DQB1*06:02, HLA-A*30:02 and HLA-B*18:01 with amoxicillin-clavulanic acid; HLA-B*57:01 with abacavir and flucloxacillin; HLA-B*13:01 with dapsone; and multiple class I and II HLA alleles with nevirapine hypersensitivity phenotypes.

Mitochondrial gene mutations may increase risk for toxicity with antimicrobial agents. Examples include 12sRNA mutations with aminoglycoside ototoxicity; linezolid-induced neurotoxicities and myelotoxicities; and peripheral neuropathy and lipoatropy with thymidine analogs.

Other key pharmacogenomics associations also exist (e.g., IL28B polymorphisms and hepatitis C treatment response), which have been relevant to treatment outcome.

Clinical practice & future role of antimicrobial pharmacogenomics

Although many antimicrobial pharmacogenomic discoveries have been made, few have translated into clinical practice. Major hurdles still exist, and clinical studies are needed in many settings.

Technological advances may improve our understanding of interactions between host, drug and pathogen genetic signatures and may better explain pathogenesis, individualize medical therapy, and result in safer and more efficacious antimicrobial therapy.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by: AI103348 to E Phillips (NIH), APP1064524 to E Phillips (NHMRC – Australia), Australian Centre for HIV and Hepatitis Virology Research (E Phillips), MH95621 to T Hulgan (NIH) and AI077505 to D Haas (NIH).

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure: The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

• of interest;

•• of considerable interest

- 1.Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2013;380(9859):2224–2260. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61766-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang G, Wang Y, Zeng Y, et al. Rapid health transition in China, 1990–2010: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2013;381(9882):1987–2015. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61097-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davison DB, Barrett JF. Antibiotics and pharmacogenomics. Pharmacogenomics. 2003;4(5):657–665. doi: 10.1517/phgs.4.5.657.23790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McNicholl JM, Downer MV, Udhayakumar V, Alper CA, Swerdlow DL. Host-pathogen interactions in emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases: a genomic perspective of tuberculosis, malaria, human immunodeficiency virus infection, hepatitis B, and cholera. Annu Rev Public Health. 2000;21(1):15–46. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.21.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tan SL, Ganji G, Paeper B, Proll S, Katze MG. Systems biology and the host response to viral infection. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25(12):1383–1389. doi: 10.1038/nbt1207-1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ho RH, Kim RB. Transporters and drug therapy: Implications for drug disposition and disease. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2005;78(3):260–277. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2005.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Minuesa G, Huber-Ruano I, Pastor-Anglada M, Koepsell H, Clotet B, Martinez-Picado J. Drug uptake transporters in antiretroviral therapy. Pharmacol Ther. 2011;132(3):268–279. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Attar M, Lee VH. Pharmacogenomic considerations in drug delivery. Pharmacogenomics. 2003;4(4):443–461. doi: 10.1517/phgs.4.4.443.22749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pavlos R, Phillips EJ. Individualization of antiretroviral therapy. Pharmacogenomics Personal Med. 2012;5:1. doi: 10.2147/PGPM.S15303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wedi B. Definitions and mechanisms of drug hypersensitivity. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2010;3(4):539–551. doi: 10.1586/ecp.10.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johansson S, Hourihane JB, Bousquet J, et al. A revised nomenclature for allergy: an EAACI position statement from the EAACI nomenclature task force. Allergy. 2001;56(9):813–824. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2001.t01-1-00001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Posadas S, Pichler W. Delayed drug hypersensitivity reactions – new concepts. Clin Exp Allergy. 2007;37(7):989–999. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2007.02742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pavlos R, Mallal S, Phillips E. HLA and pharmacogenetics of drug hypersensitivity. Pharmacogenomics. 2012;13(11):1285–1306. doi: 10.2217/pgs.12.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gil JP. Amodiaquine pharmacogenetics. Pharmacogenomics. 2008;9(10):1385–1390. doi: 10.2217/14622416.9.10.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cavaco I, Piedade R, Msellem M, Bjorkman A, Gil J. Cytochrome 1A1 and 1B1 gene diversity in the Zanzibar islands. Trop Med Int Health. 2012;17(7):854–857. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2012.03011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piedade R, Gil JP. The pharmacogenetics of antimalaria artemisinin combination therapy. Expert Opin Drug Metabol Toxicol. 2011;7(10):1185–1200. doi: 10.1517/17425255.2011.608660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kerb R, Fux R, Mörike K, et al. Pharmacogenetics of antimalarial drugs: effect on metabolism and transport. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9(12):760–774. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70320-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Phompradit P, Muhamad P, Cheoymang A, Na-Bangchang K. Preliminaryinvestigation of the contribution of CYP2A6, CYP2B6, and UGT1A9 polymorphisms on artesunate-mefloquine treatment response in Burmese patients with Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014;91(2):361–366. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.13-0531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roederer MW, McLeod H, Juliano JJ. Can pharmacogenomics improve malaria drug policy? Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89(11):838–845. doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.087320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Noedl H, Socheat D, Satimai W. Artemisinin-resistant malaria in Asia. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(5):540–541. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0900231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.di Iulio J, Fayet A, Arab-Alameddine M, et al. In vivo analysis of efavirenz metabolism in individuals with impaired CYP2A6 function. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2009;19(4):300–309. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e328328d577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haas DW, Kwara A, Richardson DM, et al. Secondary metabolism pathway polymorphisms and plasma efavirenz concentrations in HIV-infected adults with CYP2B6 slow metabolizer genotypes. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69(8):2175–2182. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kwara A, Lartey M, Sagoe KW, Kenu E, Court MH. CYP2B6, CYP2A6 and UGT2B7 genetic polymorphisms are predictors of efavirenz mid-dose concentration in HIV-infected patients. AIDS. 2009;23(16):2101–2106. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283319908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haas DW, Ribaudo HJ, Kim RB, et al. Pharmacogenetics of efavirenz and central nervous system side effects: an Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group study. AIDS. 2004;18(18):2391–2400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsuchiya K, Gatanaga H, Tachikawa N, et al. Homozygous CYP2B6*6 (Q172H and K262R) correlates with high plasma efavirenz concentrations in HIV-1 patients treated with standard efavirenz-containing regimens. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;319(4):1322–1326. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.05.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rotger M, Colombo S, Furrer H, et al. Influence of CYP2B6 polymorphism on plasma and intracellular concentrations and toxicity of efavirenz and nevirapine in HIV-infected patients. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2005;15(1):1–5. doi: 10.1097/01213011-200501000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haas DW, Smeaton LM, Shafer RW, et al. Pharmacogenetics of long-term responses to antiretroviral regimens containing efavirenz and/or nelfinavir: an Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group Study. J Infect Dis. 2005;192(11):1931–1942. doi: 10.1086/497610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rodriguez-Novoa S, Barreiro P, Rendon A, Jimenez-Nacher I, Gonzalez-Lahoz J, Soriano V. Influence of 516G>T polymorphisms at the gene encoding the CYP450-2B6 isoenzyme on efavirenz plasma concentrations in HIV-infected subjects. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40(9):1358–1361. doi: 10.1086/429327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holzinger ER, Grady B, Ritchie MD, et al. Genome-wide association study of plasma efavirenz pharmacokinetics in AIDS Clinical Trials Group protocols implicates several CYP2B6 variants. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2012;22(12):858–867. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e32835a450b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wyen C, Hendra H, Vogel M, et al. Impact of CYP2B6 983T>C polymorphism on non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor plasma concentrations in HIV-infected patients. J Antimicrob Chemo. 2008;61(4):914–918. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang J, Sonnerborg A, Rane A, et al. Identification of a novel specific CYP2B6 allele in Africans causing impaired metabolism of the HIV drug efavirenz. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2006;16(3):191–198. doi: 10.1097/01.fpc.0000189797.03845.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ribaudo HJ, Liu H, Schwab M, et al. Effect of CYP2B6, ABCB1, and CYP3A5 polymorphisms on efavirenz pharmacokinetics and treatment response: an AIDS Clinical Trials Group study. J Infect Dis. 2010;202(5):717–722. doi: 10.1086/655470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gounden V, Van Niekerk C, Snyman T, George JA. Presence of the CYP2B6 516 G> T polymorphism, increased plasma efavirenz concentrations and early neuropsychiatric side effects in South African HIV-infected patients. AIDS Res Ther. 2010;7:32. doi: 10.1186/1742-6405-7-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sánchez Martín A, Cabrera Figueroa S, Cruz Guerrero R, Hurtado LP, Hurlé ADG, Carracedo Álvarez Á. Impact of pharmacogenetics on CNS side effects related to efavirenz. Pharmacogenomics. 2013;14(10):1167–1178. doi: 10.2217/pgs.13.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gatanaga H, Hayashida T, Tsuchiya K, et al. Successful efavirenz dose reduction in HIV type 1-infected individuals with cytochrome P450 2B6* 6 and* 26. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(9):1230–1237. doi: 10.1086/522175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gatanaga H, Oka S. Successful genotype-tailored treatment with small-dose efavirenz. AIDS. 2009;23(3):433–434. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32831940e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsuchiya K, Gatanaga H, Tachikawa N, et al. Homozygous CYP2B6*6 (Q172H and K262R) correlates with high plasma efavirenz concentrations in HIV-1 patients treated with standard efavirenz-containing regimens. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;319(4):1322–1326. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.05.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Penzak SR, Kabuye G, Mugyenyi P, et al. Cytochrome P450 2B6 (CYP2B6) G516T influences nevirapine plasma concentrations in HIV-infected patients in Uganda. HIV Med. 2007;8(2):86–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2007.00432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bertrand J, Chou M, Richardson DM, et al. Multiple genetic variants predict steady-state nevirapine clearance in HIV-infected Cambodians. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2012;22(12):868–876. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e32835a5af2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vardhanabhuti S, Acosta EP, Ribaudo HJ, et al. Clinical and genetic determinants of plasma nevirapine exposure following an intrapartum dose to prevent mother-to-child HIV transmission. J Infect Dis. 2013;208(4):662–671. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Colombo S, Soranzo N, Rotger M, et al. Influence of ABCB1, ABCC1, ABCC2, and ABCG2 haplotypes on the cellular exposure of nelfinavir in vivo. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2005;15(9):599–608. doi: 10.1097/01.fpc.0000172241.42546.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saitoh A, Fletcher CV, Brundage R, et al. Efavirenz pharmacokinetics in HIV-1-infected children are associated with CYP2B6-G516T polymorphism. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;45(3):280–285. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318040b29e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yuan J, Guo S, Hall D, et al. Toxicogenomics of nevirapine-associated cutaneous and hepatic adverse events among populations of African, Asian, and European descent. AIDS. 2011;25(10):1271–1280. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834779df. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hodel EMS, Csajka C, Ariey F, et al. Effect of single nucleotide polymorphisms in cytochrome p450 isoenzyme and N-acetyltransferase 2 genes on the metabolism of artemisinin-based combination therapies in malaria patients from Cambodia and Tanzania. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57(2):950–958. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01700-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bains RK. African variation at cytochrome P450 genes: evolutionary aspects and the implications for the treatment of infectious diseases. Evol Med Public Health. 2013;2013(1):118–134. doi: 10.1093/emph/eot010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Paganotti GM, Gallo BC, Verra F, et al. Human genetic variation is associated with Plasmodium falciparum drug resistance. J Infect Dis. 2011;204(11):1772–1778. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Parikh S, Ouedraogo J, Goldstein J, Rosenthal P, Kroetz D. Amodiaquine metabolism is impaired by common polymorphisms in CYP2C8: implications for malaria treatment in Africa. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2007;82(2):197–203. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]