Abstract

Introduction Branchio-oto-renal (BOR) syndrome is an autosomal-dominant genetic condition with high penetrance and variable expressivity, with an estimated prevalence of 1 in 40,000. Approximately 40% of the patients with the syndrome have mutations in the gene EYA1, located at chromosomal region 8q13.3, and 5% have mutations in the gene SIX5 in chromosome region 19q13. The phenotype of this syndrome is characterized by preauricular fistulas; structural malformations of the external, middle, and inner ears; branchial fistulas; renal disorders; cleft palate; and variable type and degree of hearing loss.

Aim Hearing loss is part of BOR syndrome phenotype. The aim of this study was to present a literature review on the anatomical aspects and audiological profile of BOR syndrome.

Data Synthesis Thirty-four studies were selected for analysis. Some aspects when specifying the phenotype of BOR syndrome are controversial, especially those issues related to the audiological profile in which there was variability on auditory standard, hearing loss progression, and type and degree of the hearing loss. Mixed loss was the most common type of hearing loss among the studies; however, there was no consensus among studies regarding the degree of the hearing loss.

Keywords: branchio-oto-renal syndrome, BOR syndrome, hearing, review

Introduction

The etiology of hearing loss has been investigated in molecular and genetics medical centers.1 Anatomical and physiological changes in the auditory system have been described as part of the phenotype of numerous genetic syndromes, including the previously studied branchio-oto-renal (BOR) syndrome.2

The features of this clinical condition were first described in 1864 when Heusinger presented the initial reports on the association between branchial fistulas, preauricular fistulas, and hearing loss.3 However, these features combined with auricular malformations and renal anomalies, thus comprising the phenotype of a specific condition, were described almost 110 years after the first clinical reports, and it was called BOR syndrome.4 5 6

Different classifications have been applied to this condition over the years, including Melnick-Fraser syndrome. This nomenclature originates from the first phenotype descriptions by these authors, “ear pits deafness syndrome”7 and “branchio-oto-ureteral syndrome.”8 However, contemporary studies have adopted the term “BOR syndrome” in a systematic way.

The clinical characteristics that compose the BOR syndrome phenotype can be classified according to the occurrence of larger and smaller anomalies. The larger or more frequent anomalies are: (1) hearing loss (sensorineural, conductive, or mixed), (2) preauricular pits, (3) renal anomalies ranging from mild hypoplasia to agenesis, (4) brachial fistulae, and (5) stenosis of the external auditory canal. The smaller or less frequent anomalies are: (1) lacrimal duct aplasia, (2) short or cleft palate, (3) retrognathia, (4) congenital hip dysplasia, (5) facial nerve paralysis, (6) gustatory lacrimation, and (7) pancreatic cyst.9

Such anomalies are used as criteria to diagnose BOR syndrome. In other words, the presence of three major deficiencies, or the combination of two major and two smaller anomalies, or the presence of a major anomaly associated with presence of another first degree family member diagnosed with the syndrome.10

One of the most mentioned characteristics as part of the BOR syndrome phenotype is progressive hearing loss, which can be mixed, conductive, or sensorineural and can range from mild to profound.9 11 In some patients, the hearing loss has a fluctuating pattern.12 13 14 15 Studies have reported the occurrence of congenital cholesteatoma among the less common characteristics.16 17 18

Genetic/Etiologic Bases of Branchio-Oto-Renal Syndrome

The estimated rate of BOR syndrome is 1:40,000.4 5 6 9 19 BOR syndrome presents a pattern of autosomal-dominant inheritance and is considered the most common syndromic hearing loss form of genetic etiology with high penetrance and variable expressivity.4 8 19 20 21 In addition to the autosomal-dominant, mitochondrial inheritance,22 some patients present with “new” mutations.7 23 Deletions of various sizes have been found in individuals with BOR syndrome.24 25 26

The first chromosomal region associated with the syndrome was 8q12–22, identified from linkage studies in families that had multiple members affected.27 Subsequently, the detailed genetic study of this region allowed researchers to determine the chromosomal region 8q13.3 was associated with the syndrome.24 The EYA1 gene, which is responsible for the development of the branchial arches, auditory system, and kidneys, is located in this region.25 28

EYA1 gene mutations have been reported in most cases of BOR syndrome.2 29 However, studies described that in many cases of clinically diagnosed BOR syndrome, the screening for alterations in the EYA1 gene was negative, which also showed that other genes are involved in the BOR syndrome etiology, indicating a condition with genetic heterogeneity.10 30 31

Missense mutations and small deletions in the SIX1 gene, located on chromosome region 14q23.1, were also reported by several studies that described families affected by BOR syndrome.28 32 33 34 35 36 However, intrafamilial phenotypic variability can be observed in all families studied that showed mutations in SIX1.22

General Clinical Features of Branchio-Oto-Renal Syndrome

Based on the reviewed studies, the most common triad of BOR syndrome findings is: (1) hearing loss and preauricular fistulas located near the helix, (2) branchial fistulas typically found on the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, and (3) a variability of renal anomalies, which often present no symptoms. Branchial fistulas are usually located next to the first branchial arch. However, a rare case was described where the subject had four branchial fistulas located at the first and second branchial arches.37 38

A retrospective analysis of seven individuals diagnosed with BOR syndrome has shown that besides the applicant phenotype, other clinical features were found in these individuals, such as gustatory lacrimation, imperforate anus, otosclerosis, and congenital vocal cord paresis.39

The manifestations of BOR syndrome can also be composed of craniofacial abnormalities such as microcephaly,39 hemifacial microsomy,40 long face syndrome associated with lacrimal duct stenosis,5 7 14 17 41 42 overbite palate,17 and retrognathia.39 The presence of micrognathia,43 hypodontia,39 and microdontia associated with malformations of permanent molars44 were also reported. Lacrimal duct stenosis, although rare, has been described in some studies,6 7 and its occurrence is associated with gustatory lacrimation.39 41

One study described the presence of cardiac manifestation—mitral valve prolapse—in a family diagnosed with BOR syndrome (one family member had tachycardia). These symptoms were not reported in previous studies. This manifestation was identified in five of seven patients with BOR syndrome in this family, whereas hearing loss was present in all of them. Other previously described features such as branchial fistula, preauricular appendices, external ear malformation, renal anomalies, and anomalies of the lacrimal duct were found in this family.45

Limited kidney functions, bifid renal pelvis, hypoplasia, and renal cysts associated with urinary tract infections appeared in one study.20 Another study reported that such infections and glomerulonephritis episodes may be associated with normal renal anatomy and physiology.16 However, a case with a bifid kidney, double ureter, and vesicoureteric reflux46 as well as two patients who reported congenital hydronephrosis were described.40 Only one case has been described with severe reduction in kidney volume without family history of this condition,47 and there was another case with renal agenesis.48

From 1975 to 2013, several authors have described specific phenotypes in individuals diagnosed with BOR syndrome: these articles are summarized in Table 1. Most of these studies describe isolated patients or a familial nucleus and show varied expressiveness.

Table 1. Description of general findings from BOR syndrome.

|

Abbreviation: BOR, branchio-oto-renal.

Hearing loss is part of the BOR syndrome phenotype. The aim of this study was to present a literature review on the anatomical aspects and audiological profile in this condition.

Methods

This study review published studies describing BOR syndrome from 1975 to 2013. Research was performed on the following national and international databases: BIREME (Virtual Health Library—LILACS and IBECS) PubMed/MEDLINE (MEDlars onLINE), ProQuest, Web of Science (integrated into ISI Web of Knowledge), and OMIM (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man).

The following research descriptors were used according to the criteria of the MeSH:

“Branchio-Otorrenal Syndrome” and “Hearing Loss” or “Hearing Disorders”

“Branchio-Oto-Renal Syndrome” and (“Hearing” or “Hearing Disorders” or “Hearing Loss”)

“Branchio-Oto-Renal Syndrome”

Exclusion Criteria

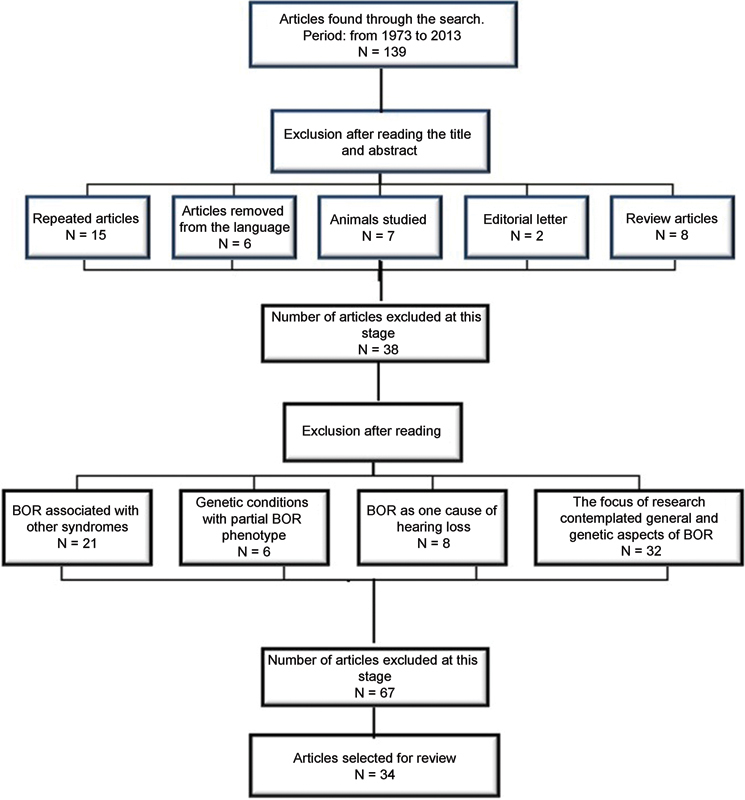

This review refers to the auditory aspects of BOR syndrome and used the following criteria for the exclusion of articles: the title and summary were not related to the purpose of the review; repeated articles and articles written in languages other than English, Portuguese, or Spanish; animal studies; editorial letters, review articles, and articles in which BOR syndrome was associated with other syndromes or genetic conditions with partial phenotype of BOR syndrome; articles that cited BOR syndrome as a cause of loss of hearing; and those that were focused only on general and genetic aspects of BOR syndrome.

From the BIREME database (LILACS and IBECS) and ProQuest, six articles were found using research descriptor 1, and five articles were excluded based on the exclusion criteria. When searching the MEDLINE database, via PubMed, using research descriptor 2, 37 articles were found, 27 of which were excluded by the criteria mentioned above, and thus 10 articles remained. The last search was performed on the Web of Science database using research descriptor 3. It resulted in 96 articles, 73 of which were excluded considering the exclusion criteria, leaving 23 remaining articles.

The results concerning literature review and discussion followed the chronological order of publication, and the issues were grouped by the descriptors used in the literature.

Fig. 1 shows the flow diagram that demonstrates the articles' selection criteria.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart demonstrating the process of deleting articles. Abbreviation: BOR, branchio-oto-renal syndrome.

Literature Review

After the application of the exclusion criteria, 34 studies were selected and compiled on Table 2, which contains the year of publication, article title, author, and number of the study participants.

Table 2. Summary of the reviewed articles' information.

| Article | Title | Author | Year | Sample |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Familial branchio-oto-renal dysplasia: a new addition to the branchial arch syndromes. | Melnick et al5 | 1976 | n = 4 (two generations) |

| 2 | Genetic aspects of the BOR syndrome—branchial fistulas, ear pits, hearing loss, and renal anomalies | Fraser et al6 | 1978 | n = 8 (three generations) |

| 3a | The earpits-deafness syndrome. Clinical and genetic aspects | Cremers, Fikkers-Van Noord7 | 1980 | n = 19 (four families) |

| 4 | Temporal bone findings in a family with branchio-oto-renal syndrome (BOR) | Ostri et al12 | 1991 | n = 19 (four generations) |

| 5 | Branchio-oto-renal (BOR) syndrome: variable expressivity in a five-generation pedigree | König et al20 | 1994 | n = 6 (four generations) |

| 6 | Phenotypic manifestations of branchio-oto-renal syndrome | Chen et al19 | 1995 | n = 32 |

| 7 | Branchio-oto-renal syndrome | Millman et al38 | 1995 | n = 1 |

| 8 | Renal failure and deafness: branchio-oto-renal syndrome | Misra, Nolph43 | 1998 | n = 1 |

| 9 | Congenital cholesteatoma and malformations of the facial nerve: rare manifestations of the BOR syndrome | Graham et al16 | 1999 | n = 2 |

| 10 | New' manifestations of BOR syndrome | Weber, Kousseff39 | 1999 | n = 7 |

| 11 | Bilateral congenital cholesteatoma in branchio-oto-renal syndrome | Worley et al17 | 1999 | n = 1 |

| 12 | Branchio-oto-renal syndrome with generalized microdontia | Prabhu et al44 | 1999 | n = 1 |

| 13 | EYA1 nonsense mutation in a Japanese branchio-oto-renal syndrome family | Usami et al54 | 1999 | n = 3 (two generations) |

| 14 | Temporal bone computed tomography findings in bilateral sensorineural hearing loss | Bamiou et al55 | 2000 | n = 3 |

| 15 | Branchio-oto-renal syndrome: a report on nine family groups | Bellini et al42 | 2001 | n = 10 (nine families) |

| 16 | The presence of a widened vestibular aqueduct and progressive sensorineural hearing loss in the branchio-oto-renal syndrome. A family study | Stinckens et al14 | 2001 | n = 12 |

| 17 | Progressive fluctuant hearing loss, enlarged vestibular aqueduct, and cochlear hypoplasia in branchio-oto-renal syndrome | Kemperman et al13 | 2001 | n = 2 (two generations) |

| 18 | Visualization of inner ear dysplasias in patients with sensorineural hearing loss | Klingebiel et al57 | 2001 | n = 2 |

| 19 | Inner ear anomalies are frequent but nonobligatory features of the branchio-oto-renal syndrome | Kemperman et al58 | 2002 | n = 35 (six families) |

| 20 | A family with the branchio-oto-renal syndrome: clinical and genetic correlations | Pierides et al46 | 2002 | n = 10 (two generations) |

| 21 | Temporal bone anomalies in the branchio-oto-renal syndrome: detailed computed tomographic and magnetic resonance imaging findings | Ceruti et al15 | 2002 | n = 8 (four generations) |

| 22 | Síndrome branquio-oto-renal y colesteatoma congénito | Adiego et al18 | 2003 | n = 1 |

| 23 | Evidence of progression and fluctuation of hearing impairment in branchio-oto-renal syndrome | Kemperman et al53 | 2004 | n = 32 (six families) |

| 24 | Temporal bone findings on computed tomography imaging in branchio-oto-renal syndrome | Propst et al59 | 2005 | n = 21 |

| 25a | Non-inherited manifestation of bilateral branchial fistulae, bilateral pre-auricular sinuses and bilateral hearing loss: a variant of branchio-oto-renal syndrome | Rana et al23 | 2005 | n = 1 |

| 26 | Identification of a novel mutation in the EYA1 gene in a Korean family with branchio-oto-renal (BOR) syndrome | Kim et al49 | 2005 | n = 2 (two generations) |

| 27 | Cochlear implantation in branchio-oto-renal syndrome—a surgical challenge | Kameswaran et al56 | 2007 | n = 1 |

| 28 | Branchio-oto-renal syndrome | Garg et al47 | 2008 | n = 1 |

| 29 | Achados genéticos, audiológicos e da linguagem oral de um núcleo familial com diagnóstico da síndrome Branquio-oto-renal (SBOR) | Furlan et al51 | 2008 | n = 7 (two generations) |

| 30 | From a branchial fistula to a branchiootorenal syndrome: a case report and review of the literature | Senel et al50 | 2009 | n = 1 |

| 31 | Mitral valve prolapse as a new finding in branchio-oto-renal syndrome | Ayçiçek et al45 | 2010 | n = 1 |

| 32 | Diagnostic and surgical challenge: middle ear dermoid cyst in 12 month old with branchio-oto-renal syndrome and multiple middle-ear congenital anomalies | Johnston et al40 | 2011 | n = 1 |

| 33 | Young woman with branchio-oto-renal syndrome and a novel mutation in the EYA-1 gene | Nardi et al48 | 2011 | n = 1 |

| 34 | Congenital unilateral facial nerve palsy as an unusual presentation of BOR syndrome | Jankauskienè, Azukaitis52 | 2013 | n = 1 |

Syndrome manifestation as a noninherited characteristic.

Results

Anatomical Changes and Audiological Profile

In the studies reviewed, a prevalence of mixed hearing loss was observed, followed by conductive and sensorineural hearing loss. Some studies reported that the presence of chronic or recurrent otitis media is an aggravating factor for hearing loss, which may be associated with ossicular chain malformations or alterations, or presence of cleft palate, increasing the number with conductive/mixed hearing loss.6 16 20 49 50 51 There was a higher recurrence of moderate and severe hearing loss among the studies' participants, probably due to the number of abnormalities found in the inner ear, which encompasses cochlear alterations to malformation of the vestibular system.

Some research verified that in addition to the auditory standards mentioned above, hearing loss could maintain a progressive and/or fluctuating pattern,6 13 14 15 19 46 52 which contradicts other studies that related their standard as stable.12 16 19 53 A retrospective study identified significant hearing loss progression in 10 patients. The results demonstrated that in seven patients, the hearing loss was fluctuating; however, this fluctuation was only significant in young patients.52 A study reported that patients with an enlarged endolymphatic sac or duct had hearing thresholds significantly higher than in those patients without such abnormalities,52 which corroborates the study of Kemperman et al, 2001.13

In the literature, a description was found of three patients with BOR syndrome who also had cholesteatoma. In one of them, the cholesteatoma was in the temporal bone cavity, bilaterally, and showed no association with the facial nerve alterations. However, the other patients showed facial nerve alterations. One subject had facial nerve paralysis on the left side and in the other subject had right-side paralysis.16 17 18 54

Cochlear implant in BOR syndrome was first used in a 3-year-old with congenital profound hearing loss and impaired language and speech development. Radiologic evaluation of the temporal bone and the inner ear showed severe dysplasia of the vestibule, ossicles, and bilaterally malformed semicircular canals and facial nerve posteriorly positioned. Three weeks after implantation, initial mapping showed positive responses. After hearing habilitation, the patient was able to recognize speech stimuli in a closed set.55

Radiologic studies and magnetic resonance imaging of the mastoid and middle ear showed several types of middle and inner ear pathology, among them: (1) hypoplasia, malformation and displacement of the ossicular chain, such as the junction of the hammer and anvil fixing the malleus in the tympanic membrane, and calcified oval window; (2) malformations—enlargement—and asymmetry of the semicircular canals/ducts and endolymphatic sac; and (3) cochlear hypoplasia or dysplasia.6 7 14 49 50 53 56 57 58

A study retrospectively assessed tomographic findings of 21 subjects (42 ears) with a clinical diagnosis of BOR syndrome, based on criteria derived from genotype and phenotype, and described the most common and easily identifiable features of BOR syndrome by visual inspection. The results of this assessment were: (1) apical cochlear hypoplasia was present in all individuals with BOR syndrome and no subject had normal hearing, (2) the facial nerve was diverted to the medial side of the cochlea in 38 of 42 ears, and (3) the inner ear channel was funnel-shaped in 36 of the 42 ears.59

Discussion

The phenotypic features related to the most-mentioned anatomical ear alterations in BOR syndrome were: malformation; hyperplasia and low implantation of the ear; narrowing of the external acoustic meatus; ossicular chain abnormalities; reduced size of the middle ear cavity; otosclerosis; semicircular canal anomalies involving hypoplasia, dysplasia, and enlargement of the endolymphatic duct and sac; and cochlear hypoplasia.

The audiological profile, considering the type and degree of hearing loss and the association of the auditory system characteristics, is presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Auditory system characteristics and description of hearing loss in BOR syndrome.

| Article | Type | Degree | Pattern | Anatomic changes: external, middle, and inner ear |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melnick et al5 | Mixed | – | – | Mondini-type cochlear malformation and stapes fixation |

| Fraser et al6 | Conductive/mixed | Mild to severe | Progressive | OC changes, ME fluid, otosclerosis |

| Cremers, Fikkers-Van Noord7 | Conductive/mixed/sensorineural | – | – | Cochlear hypoplasia/dysplasia, narrow or wide internal auditory canal, OC anomalies, horizontal SC with reduced size |

| Ostri et al12 | Mixed | Moderate to severe | Stable | Cochlear hypoplasia, SC hypoplasia and abnormal duct endolymphatic, massive OC and reduced size of ME |

| König et al20 | Mixed | Severe | – | Malformation of OC |

| Chen et al19 | Conductive/mixed/sensorineural | Mild to profound | Progressive/stable | Stenosis of the EEC, malformation of OC, cochlear hypoplasia/dysplasia and enlargement of the endolymphatic duct |

| Millman et al38 | – | Severe | – | – |

| Misra, Nolph43 | Mixed | Moderate to severe | – | Changes in OC |

| Graham et al16 | Conductive | Moderate | Stable | Cholesteatoma, absence or abnormality of the ossicles and oval window, TM retraction |

| Weber, Kousseff39 | Conductive/sensorineural | Mild to moderate | – | Otosclerosis |

| Worley et al17 | Mixed | Moderate | – | Cholesteatoma, OC anomalies, otitis media—ventilation tubes |

| Prabhu et al44 | Mixed | – | – | Malformed and hyperplastic right pinna and a preauricular pit on the left ear |

| Usami et al54 | Conductive/mixed | Mild to moderate | Stable | Cochlear hypoplasia of the lateral and posterior semicircular canal, abnormal OC, soft mass density in the epitympanic and mastoid cavity |

| Bamiou et al55 | – | – | – | Mondini-type cochlear malformation |

| Bellini et al42 | Conductive/mixed/sensorineural | – | – | – |

| Stinckens et al14 | Sensorineural | – | Progressive | Enlarged vestibular aqueduct, cochlear hypoplasia |

| Kemperman et al13 | Sensorineural | Profound | Progressive/fluctuant | Cochlear hypoplasia, enlarged vestibular aqueduct |

| Klingebiel et al57 | – | – | – | Dysplasia of the SC superior, cochlear hypoplasia (1.5 turn) |

| Kemperman et al58 | – | – | – | Enlarged vestibular aqueduct, hypoplastic cochleae and labyrinths, malformed auricles |

| Pierides et al46 | – | – | Progressive | – |

| Ceruti et al15 | Sensorineural | – | Progressive | Cochlear hypoplasia/dysplasia, SC malformations, OC malformations |

| Adiego et al18 | Mixed | Moderate | – | EEC stenosis, cholesteatoma, OC malformation, cochlear hypoplasia, abnormal morphology of the SC |

| Kemperman et al53 | – | – | Progressive/fluctuant | Enlarged vestibular aqueduct, medial deviation of facial nerve, cochlear hypoplasia |

| Propst et al59 | – | – | – | Cochlear hypoplasia, narrowed internal auditory canal |

| Rana et al23 | – | – | – | Pneumatic temporal bone, partial agenesis of the EEC |

| Kim et al49 | Mixed | Moderate to profound | – | EEC stenosis, dense mass in the mastoid and tympanic cavity, cochlear hypoplasia, enlarged vestibular aqueduct, OC malformation, otitis media |

| Kameswaran et al56 | Sensorineural | Profound | – | Vestibular dysplasia, SC and ossicles malformation |

| Garg et al47 | – | Moderate to profound | – | – |

| Furlan et al51 | Conductive/mixed | Mild to moderate to severe | – | – |

| Senel et al50 | Conductive/mixed | Mild to moderate | – | EEC stenosis, auricular malformation, cochlear and SC hypoplasia, OC malformation |

| Ayçiçek et al45 | – | – | – | EE and IE malformation |

| Johnston et al40 | Mixed | Moderate to severe | – | Cochlear hypoplasia, OC malformation, enlarged vestibular aqueduct |

| Nardi et al48 | – | – | – | Enlarged vestibular aqueduct |

| Jankauskienè, Azukaitis52 | – | – | – | Uncertain results of otoacoustic emission and facial nerve paralysis at the RE |

Abbreviations: EE, external ear; EEC, external ear canal; IE, inner ear; ME, middle ear; OC, ossicular chain; RE, right ear; SC, semicircular canals; TM, tympanic membrane.

The analysis of these studies showed that there was a high frequency of mixed hearing loss (33.72%) followed by sensorineural (10.98%) and conductive hearing loss (7.84%); however, in 47.45% of the articles, this information was not present. The degree of hearing loss was classified as moderate in 12.94% of the articles, mild in 6.66%, severe in 6.27%, and profound in 4.73%. This information was not present in 67.84% of the articles. Only 29.4% of the studies described the hearing loss pattern, which was classified as stable, progressive, or fluctuating.

Conclusion

Because hearing loss is mentioned in a great number of BOR syndrome studies. Deafness linked to preauricular fistula, branchial fistulae, and renal anomalies should be investigated and monitored by a multidisciplinary team, mainly otorhino-laryngologic professionals.

Due to the variable phenotypic expression described, many cases of BOR syndrome may have been underdiagnosed, and sometimes the diagnosis is delayed, even in cases where the hearing impairment is severe and interferes with the development of language and speech.

This review shows that some aspects remain controversial due to syndrome variability and the difficulty of early diagnosis, especially in issues related to the audiological profile where there is a great variability in the auditory pattern and the hearing loss progression, type, and degree. Most studies described that mixed hearing loss is the most common type; however, there is no consensus about the degree.

In the 40 years of research on BOR syndrome, studies were aimed at characterization of the phenotype of this syndrome, and the hearing loss was mentioned as part of the phenotype; however, few specific studies characterize the hearing loss standard, type, and degree.

References

- 1.Ramos P Z, de Moraes V CS, Svidnicki M CCM, Soki M N, Castilho A M, Sartorato E L. Etiologic and diagnostic evaluation: algorithm for severe to profound sensorineural hearing loss in Brazil. Int J Audiol. 2013:1–7. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2013.817689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kniffin C L Branchiootorenal syndrome 1; BOR1. OMIM 2012 Available at: http://omim.org/entry/113650. Access date: 10/07/2013.

- 3.Heusinger C F. Hals-Kiemen-Fisteln von noch nicht beobachteter form. Virchows. Arch Path Anat. 1864;29:338–380. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Melnick M, Bixler D, Silk K, Yune H, Nance W E. Autosomal dominant branchiootorenal dysplasia. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser. 1975;11:121–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Melnick M, Bixler D, Nance W E, Silk K, Yune H. Familial branchio-oto-renal dysplasia: a new addition to the branchial arch syndromes. Clin Genet. 1976;9:25–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1976.tb01546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fraser F C, Ling D, Clogg D, Nogrady B. Genetic aspects of the BOR syndrome—branchial fistulas, ear pits, hearing loss, and renal anomalies. Am J Med Genet. 1978;2:241–252. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320020305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cremers C W, Fikkers-Van Noord M. The earpits-deafness syndrome. Clinical and genetic aspects. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1980;2:309–322. doi: 10.1016/0165-5876(80)90036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fraser F C, Aymé S, Halal F, Sproule J. Autosomal dominant duplication of the renal collecting system, hearing loss, and external ear anomalies: a new syndrome? Am J Med Genet. 1983;14:473–478. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320140311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith R JH Schwartz C Branchio-oto-renal syndrome J Commun Disord 199831411–420., quiz 421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang E H, Menezes M, Meyer N C. et al. Branchio-oto-renal syndrome: the mutation spectrum in EYA1 and its phenotypic consequences. Hum Mutat. 2004;23:582–589. doi: 10.1002/humu.20048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fraser F C, Sproule J R, Halal F. Frequency of the branchio-oto-renal (BOR) syndrome in children with profound hearing loss. Am J Med Genet. 1980;7:341–349. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320070316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ostri B, Johnsen T, Bergmann I. Temporal bone findings in a family with branchio-oto-renal syndrome (BOR) Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1991;16:163–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.1991.tb01969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kemperman M H, Stinckens C, Kumar S, Huygen P L, Joosten F B, Cremers C W. Progressive fluctuant hearing loss, enlarged vestibular aqueduct, and cochlear hypoplasia in branchio-oto-renal syndrome. Otol Neurotol. 2001;22:637–643. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200109000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stinckens C, Standaert L, Casselman J W. et al. The presence of a widened vestibular aqueduct and progressive sensorineural hearing loss in the branchio-oto-renal syndrome. A family study. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2001;59:163–172. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5876(01)00473-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ceruti S, Stinckens C, Cremers C W, Casselman J W. Temporal bone anomalies in the branchio-oto-renal syndrome: detailed computed tomographic and magnetic resonance imaging findings. Otol Neurotol. 2002;23:200–207. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200203000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Graham G E, Allanson J E. Congenital cholesteatoma and malformations of the facial nerve: rare manifestations of the BOR syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1999;86:20–26. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19990903)86:1<20::aid-ajmg5>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Worley G A, Vats A, Harcourt J, Albert D M. Bilateral congenital cholesteatoma in branchio-oto-renal syndrome. J Laryngol Otol. 1999;113:841–843. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100145359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hernández Montero E, Adiego I, Clau F, Fraile J, Llorente E, Ortiz García A. Síndrome branquio-oto-renal y colesteatoma congénito. O.R.L.-DIPS. 2003;30:222–225. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen A, Francis M, Ni L. et al. Phenotypic manifestations of branchio-oto-renal syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1995;58:365–370. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320580413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.König R, Fuchs S, Dukiet C. Branchio-oto-renal (BOR) syndrome: variable expressivity in a five-generation pedigree. Eur J Pediatr. 1994;153:446–450. doi: 10.1007/BF01983410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stratakis C A, Lin J-P, Rennert O M. Description of a large kindred with autosomal dominant inheritance of branchial arch anomalies, hearing loss, and ear pits, and exclusion of the branchio-oto-renal (BOR) syndrome gene locus (chromosome 8q13.3) Am J Med Genet. 1998;79:209–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mosrati M A, Hammami B, Rebeh I B. et al. A novel dominant mutation in SIX1, affecting a highly conserved residue, result in only auditory defects in humans. Eur J Med Genet. 2011;54:e484–e488. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rana I, Dhawan R, Gudwani S, Bothra R, Mathur N N. Non-inherited manifestation of bilateral branchial fistulae, bilateral pre-auricular sinuses and bilateral hearing loss: a variant of branchio-oto-renal syndrome. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;57:52–54. doi: 10.1007/BF02907630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ni L, Wagner M J, Kimberling W J. et al. Refined localization of the branchiootorenal syndrome gene by linkage and haplotype analysis. Am J Med Genet. 1994;51:176–184. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320510222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abdelhak S, Kalatzis V, Heilig R. et al. A human homologue of the Drosophila eyes absent gene underlies branchio-oto-renal (BOR) syndrome and identifies a novel gene family. Nat Genet. 1997;15:157–164. doi: 10.1038/ng0297-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vincent C, Kalatzis V, Abdelhak S. et al. BOR and BO syndromes are allelic defects of EYA1. Eur J Hum Genet. 1997;5:242–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumar S, Kimberling W J, Kenyon J B, Smith R JH, Marres H A, Cremers C WRJ. Autosomal dominant branchio-oto-renal syndrome—localization of a disease gene to chromosome 8q by linkage in a Dutch family. Hum Mol Genet. 1992;1:491–495. doi: 10.1093/hmg/1.7.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruf R G, Xu P X, Silvius D. et al. SIX1 mutations cause branchio-oto-renal syndrome by disruption of EYA1-SIX1-DNA complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:8090–8095. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308475101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stockley T L, Mendoza-Londono R, Propst E J, Sodhi S, Dupuis L, Papsin B C. A recurrent EYA1 mutation causing alternative RNA splicing in branchio-oto-renal syndrome: implications for molecular diagnostics and disease mechanism. Am J Med Genet A. 2009;149A:322–327. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rodríguez-Soriano J, Vallo A, Bilbao J R, Castaño L. Branchio-oto-renal syndrome: identification of a novel mutation in the EYA1 gene. Pediatr Nephrol. 2001;16:550–553. doi: 10.1007/s004670100603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vervoort V S, Smith R JH, O'Brien J. et al. Genomic rearrangements of EYA1 account for a large fraction of families with BOR syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet. 2002;10:757–766. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ito T, Noguchi Y, Yashima T, Kitamura K. SIX1 mutation associated with enlargement of the vestibular aqueduct in a patient with branchio-oto syndrome. Laryngoscope. 2006;116:796–799. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000209096.40400.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sanggaard K M, Rendtorff N D, Kjaer K W. et al. Branchio-oto-renal syndrome: detection of EYA1 and SIX1 mutations in five out of six Danish families by combining linkage, MLPA and sequencing analyses. Eur J Hum Genet. 2007;15:1121–1131. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kochhar A, Orten D J, Sorensen J L. et al. SIX1 mutation screening in 247 branchio-oto-renal syndrome families: a recurrent missense mutation associated with BOR. Hum Mutat. 2008;29:565. doi: 10.1002/humu.20714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krug P, Moriniere V, Marlin S. et al. Mutation screening of the EYA1, SIX1 and SIX5 genes in a large cohort of patients harboring branchio-oto-renal syndrome calls into question the pathogenic role of SIX5 mutations. Hum Mutat. 2011;32:183–190. doi: 10.1002/humu.21402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nie X, Sun J, Gordon R E, Cai C L, Xu P X. SIX1 acts synergistically with TBX18 in mediating ureteral smooth muscle formation. Development. 2010;137:755–765. doi: 10.1242/dev.045757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gutierrez C B, Bardají C, Bento L, Martinez M A, Conde J. Branchio-oto-renal syndrome: incidence in three generations of a family. J Pediatr Surg. 1993;28:1527–1529. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(93)90086-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Millman B, Gibson W S, Foster W P. Branchio-oto-renal syndrome. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;121:922–925. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1995.01890080088017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weber K M, Kousseff B G. New' manifestations of BOR syndrome. Clin Genet. 1999;56:306–312. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.1999.560408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johnston D R, Whittemore K, Poe D, Robson C D, Perez-Atayde A R. Diagnostic and surgical challenge: middle ear dermoid cyst in 12 month old with branchio-oto-renal syndrome and multiple middle-ear congenital anomalies. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;75:1341–1345. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2011.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Preisch J W, Bixler D, Ellis F D. Gustatory lacrimation in association with the branchio-oto-renal syndrome. Clin Genet. 1985;27:506–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1985.tb00240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bellini C, Piaggio G, Massocco D. et al. Branchio-oto-renal syndrome: a report on nine family groups. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;37:505–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Misra M, Nolph K D. Renal failure and deafness: branchio-oto-renal syndrome. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998;32:334–337. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.1998.v32.pm9708623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Prabhu N T, Alexander S, John R. Branchio-oto-renal syndrome with generalized microdontia: case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1999;87:180–183. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(99)70270-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ayçiçek A, Sağlam H, Koçoğullari C U, Haktanir N T, Dereköy F S, Solak M. Mitral valve prolapse as a new finding in branchio-oto-renal syndrome. Clin Dysmorphol. 2010;19:181–184. doi: 10.1097/MCD.0b013e32832cfdc9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pierides A M, Athanasiou Y, Demetriou K, Koptides M, Deltas C C. A family with the branchio-oto-renal syndrome: clinical and genetic correlations. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17:1014–1018. doi: 10.1093/ndt/17.6.1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Garg A, Wadhera R, Gulati S P, Kumar A. Branchio-oto-renal syndrome. J Assoc Physicians India. 2008;56:904–905. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nardi E, Palermo A, Cusimano P, Mulè G, Cerasola G. Young woman with branchio-oto-renal syndrome and a novel mutation in the EYA-1 gene. Clin Nephrol. 2011;76:330–333. doi: 10.5414/cn106676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim S H, Shin J H, Yeo C K. et al. Identification of a novel mutation in the EYA1 gene in a Korean family with branchio-oto-renal (BOR) syndrome. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;69:1123–1128. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Senel E, Kocak H, Akbiyik F, Saylam G, Gulleroglu B N, Senel S. From a branchial fistula to a branchiootorenal syndrome: a case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44:623–625. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2008.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Furlan R H Rossi N F Cardoso A CV Richieri-Costa A Motonaga S M Giacheti C M Achados genéticos, audiológicos e da linguagem oral de um núcleo familial com diagnóstico da síndrome Branquio-oto-renal (SBOR) Paper presented at: XVI Congresso Brasileiro de Fonoaudiologia; September 24–27, 2008; Campos do Jordão, São Paulo, Brasil

- 52.Jankauskienè A, Azukaitis K. Congenital unilateral facial nerve palsy as an unusual presentation of BOR syndrome. Eur J Pediatr. 2013;172:273–275. doi: 10.1007/s00431-012-1795-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kemperman M H, Koch S M, Kumar S, Huygen P L, Joosten F B, Cremers C W. Evidence of progression and fluctuation of hearing impairment in branchio-oto-renal syndrome. Int J Audiol. 2004;43:523–532. doi: 10.1080/14992020400050067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Usami S, Abe S, Shinkawa H, Deffenbacher K, Kumar S, Kimberling W J. EYA1 nonsense mutation in a Japanese branchio-oto-renal syndrome family. J Hum Genet. 1999;44:261–265. doi: 10.1007/s100380050156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bamiou D E, Phelps P, Sirimanna T. Temporal bone computed tomography findings in bilateral sensorineural hearing loss. Arch Dis Child. 2000;82:257–260. doi: 10.1136/adc.82.3.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kameswaran M, Kumar R SA, Murali S, Raghunandhan S, Karthikeyan K. Cochlear implantation in branchio-oto-renal syndrome—a surgical challenge. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;59:280–283. doi: 10.1007/s12070-007-0081-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Klingebiel R, Bockmühl U, Werbs M. et al. Visualization of inner ear dysplasias in patients with sensorineural hearing loss. Acta Radiol. 2001;42:574–581. doi: 10.1080/028418501127347403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kemperman M H, Koch S M, Joosten F B, Kumar S, Huygen P L, Cremers C W. Inner ear anomalies are frequent but nonobligatory features of the branchio-oto-renal syndrome. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;128:1033–1038. doi: 10.1001/archotol.128.9.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Propst E J, Blaser S, Gordon K A, Harrison R V, Papsin B C. Temporal bone findings on computed tomography imaging in branchio-oto-renal syndrome. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:1855–1862. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000177032.98386.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]