Abstract

Introduction The family has ultimate responsibility for decisions about the use and care during the daily routine and problem solving in the manipulation of hearing aids (HA) in infants and children.

Objective The purpose of the study was to assess technical and content quality of Babies' Portal website Hearing Aid section by audiologists.

Methods Letters and e-mails were sent inviting professionals to surf the website and anonymously fill out an online form with 58 questions covering demographic data as well as the website's technical (Emory questionnaire with the subscales of accuracy, authorship, updates, public, navigation, links, and structure) and content quality.

Results A total of 109 professionals (tree men and 106 women) with mean age of 31.6 years participated in the study. Emory percentage scores ranged from 90.1 to 96.7%. The Hearing Aid section contents were considered good or very good.

Conclusion The website was deemed to have good technical and content quality, being suitable to supplement informational counseling to parents of hearing-impaired children fitted with hearing aids.

Keywords: hearing loss, hearing aids, audiology, counseling, telehealth, internet

Introduction

Parents of hearing-impaired children need to understand the information regarding hearing loss and treatment options to make the best decisions.1 Thus, it is necessary that such information is clear and easy to access and provided in a systematic form.2 Educational materials elaborated in a simple and accessible language should be provided to parents to access after appointments, thus respecting the time to assimilate the content.3

The Internet can be a useful source of information and support for a wide range of chronic conditions, providing decentralization and democratization of access, avoiding various obstacles like time, geographical location, and physical and personal barriers.4 Patients' education through the Internet can also help solve the challenge of reconciling the needs and expectations of patients with the health system characteristics and limitations.5

In an international health survey, 12,000 people in 12 countries were interviewed, and it was verified that 81% of the Internet users use the network to search for health information. Brazilians are in fourth place among those who use the Internet to search for health information: of 1,005 individuals interviewed, 86% with the Internet access used it to seek information on health orientation, medicine, and their medical conditions. However, only 25% also checked the source of the data.6

An Australian study showed that 67% of parents with hearing-impaired children feel comfortable in seeking information about hearing on the Internet. These surveys are conducted via generic search engine (87%). Parents also visits websites that appear to be specialized in hearing loss (44%) or those recommended by other parents (31%).7

However, the popularity and the increase of health information available online presents new challenges regarding the quality of information, which is often incomplete and inaccurate due to the economic or other interests of the information producers.8 9

The evaluation of the information available on the Internet, in English, for hearing-impaired adults and their families found that most existing websites were of commercial origin and their quality and readability were highly variable. Only 14% of the websites had quality certification.10

Several assessment tools have been developed with the purpose of directing consumers to good information sources. The tools include different items that are considered essential for a good-quality website. These tools are generally generic and can be applied to websites focused on different health conditions. Measuring the clinical impact and the consumer ability to learn the content found online should also be considered when evaluating a website.11 Given that the importance of evaluating the information available online is a relatively recent concern, there are still no standardized instruments that are sufficiently validated.

The Hearing Aid section on the Babies' Portal website (http://portaldosbebes.fob.usp.br) was created to provide parents and caregivers of hearing-impaired children convenient access and daily guidelines regarding the use and care of hearing aids (HA) and earmold, as well as the resolution of the main problems encountered during the use of HAs. This website can be used as a tool to assist with parental counseling. For this reason, the aim of this study was to evaluate the technical and content quality of the Babies' Portal Hearing Aid section.

Methods

This cross-exploratory study was conducted at the Speech-Language Pathology and Audiology Department of Bauru School of Dentistry, Universidade de São Paulo, after the institution's Research Ethics Committee reviewed and approved the study (process number 009/2009).

Audiologists working in 144 audiology services (79 high-complexity services and 65 medium-complexity services) accredited by the Health Ministry at the time of the study and in private practices were invited to participate in the study. The invitation to professionals from public services was conducted by mail, in which the correspondences were sent to the service. The Babies' Portal website was advertised on the Brazilian Audiology Academy website, thus sending the invitation to participate in the study to all members through e-mail.

The invitation contained an explanation of the study's purpose and the address to access and browse the website, as well as the link to rate the website. In this link, the consent form and the online evaluation form were included. Participants were asked to access and navigate the Babies' Portal website Hearing Aid section and afterward anonymously fill out an online evaluation form, composed of four parts, detailed below.

Part 1 (Question 1)

Information regarding the questionnaire and the consent form was solicited, with two response options: “I do not want to participate” (the user was directed to a page thank them, without access to the evaluation form) and “I want to participate” (the individual was directed to the evaluation questionnaire).

Part 2 (Questions 2 to 21)

Questions were asked relating to data such as demographics (age, sex, region of residence), degree, work area, Internet usage, and issues related to the participant's judgment of its performance on counseling infant and children with HA fitting, providing materials, and time spent on counseling.

Part 3 (Questions 22 to 57)

Part 3 consisted of an adaptation of the Emory Health-Related website's evaluation form.11

The Emory tool is composed of 36 questions divided into eight subscales/categories:

Content (six items): assesses the website content, if the purpose is clear, discusses all aspects of the theme

Accuracy (three items): assesses the content reliability

Authorship (three items): assesses whether the authors provide information about their schooling and their contact

Updates (two items): assesses whether the website provides current information that follows newly published scientific material in the studied area and if this update is clearly available to the audience

Public (four items): evaluates if the website identifies to whom the information is intended, and the detail and reading levels

Navigation (six items): assesses the navigability, that is, whether there are errors when opening certain pages, if the website takes time to load information, if it has a search tool

External Links (six items): assesses if the website provides external links to other websites to complement its information, and assesses whether the external links provided are appropriate

Structure (six items): assesses how the information is displayed, if it allows disabled people to access (for example, the option to increase the font for the visually impaired), if there are illustrations, videos, and audios

For each item, the response options were agree (2 points), disagree (1 point) and, for some items, not applicable was also an option (0 points). The subscale score was the sum of the items' points. The website total score was the sum of all subscales scores.

We also calculated the number of possible points in each category and for the entire questionnaire—that is, the number of items answered either agree or disagree, multiplied by 2. Thus, the possible points were particular to a given questionnaire completion. To obtain the results expressed as a percentage (subitem or total), the score was divided by the highest possible (subitem or total) score. This result was then multiplied by 100. The final percentage obtained indicates the website quality:

At least 90%: Excellent. The website is an excellent source of health information. Consumers can easily access and understand the information in this website. Do not hesitate in referring this website to your customers.

At least 75%: Suitable. The website provides relevant information and can be navigated without a lot of problems; however, it may not be the best website available. If another source of information cannot be located, this website will provide good information for your customer. Caution should be taken when you talk to your client about the information found on the website and the information that is actually required.

Less than 75%: Poor. This website should not be recommended to clients. The validity and reliability of the information cannot be confirmed. Not all information on the website may be accessible. Look for another website to prevent reading false or partial information.

Part 4 (Question 58)

Question 58 assessed the content quality. The Babies' Portal Hearing Aid section main topics were presented, which included: general knowledge regarding the HA, the HA function, what an HA is, different types and technologies, questions regarding the earmold and HA care and use, troubleshooting, and how to create an HA daily use routine. Participants were asked to choose the answer that was close to their judgment. The response options were provided on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from very bad (1 point) to very good (5 points). The higher the score, the better the content quality assessment. If the participant had not accessed a particular content in the portal, the option “not accessed” should be selected, thus not assigned any score.

At the end of the questionnaire, space was available for suggestions and comments.

The total score and the number of possible points were calculated. The number of possible points is equal to the number of items answered multiplied by 5. Thus the total possible score was particular to a given questionnaire completion. To express the result as a percentage, the total score of the content was given by the total points earned divided by the total possible score. This result was then multiplied by 100.

The existence of different scores on Emory questionnaire subscales and between the items evaluated on the content has been verified by the nonparametric Friedman. The nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test was used to assess whether there were differences between the Emory questionnaire overall score and subscales, as well as between the overall score and rating according to the region the professional worked in Brazil. Correlations (Spearman) were obtained between professional experience and Emory subscales. In all cases, the significance level was 5%.

Results

During the data collection period, 173 professionals accessed the link to rate the site from Babies' Portal and 172 agreed to participate. Of these, 63 subjects were excluded due to not fulfilling the information in the evaluation questionnaire. In total, the study included 109 participants who completed at least one of the website questionnaires evaluation, 3 men (2.8%) and 106 women (97.2%), age from 19 to 59 years old (mean = 31.6 years; standard deviation [SD] = 7.4). Of these, 102 participants completed the website technical and content quality evaluation and 7 only completed the technical evaluation.

Regarding the region of practice, participants were divided into southeast (n = 64; 58.7%), south (n = 23; 21.1%), north (n = 6; 5.5%), northeast (n = 9; 8.3%), and midwest (n = 7; 6.4%). For data analysis purposes, the participants in the north, northeast, and midwest were grouped (n = 22, 20.2%).

The time for completing the evaluation form varied from 10 minutes to 2 hours and 50 minutes (mean = 55.6 minutes; SD = 45.1). Data regarding the frequency of Internet use by health professionals were obtained (Table 1).

Table 1. Frequent Internet access referred by the professional (n = 109).

| Regions | Frequency of Internet use | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequently (several times a day), n (%) | Usually (several times a week), n (%) | Occasionally (once or twice a week), n (%) | |

| Southeast (n = 64) | 54 (84.4) | 9 (16.7) | 1 (1.6) |

| South (n = 23) | 16 (69.6) | 6 (26.1) | 1 (4.3) |

| NNM (n = 22) | 18 (81.8) | 4 (18.2) | 0 |

| Total (n = 109) | 88 (80.7) | 19 (17.4) | 2 (1.8) |

Abbreviation: NNW, north, northeast and midwest.

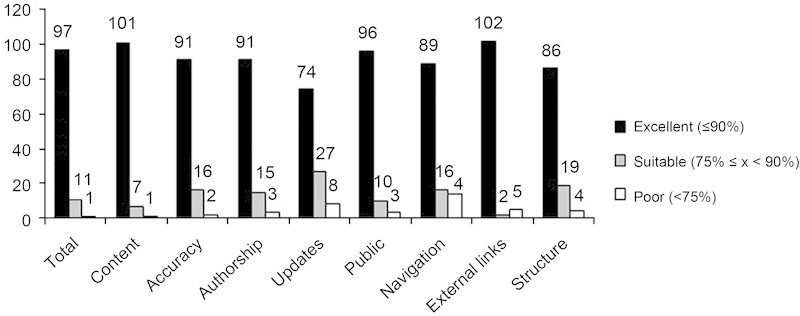

The website technical quality measured by the Emory questionnaire in the different subscales was considered excellent for the vast majority of participants (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Website quality classification distribution from Emory questionnaire subscales scores and total score (n = 109).

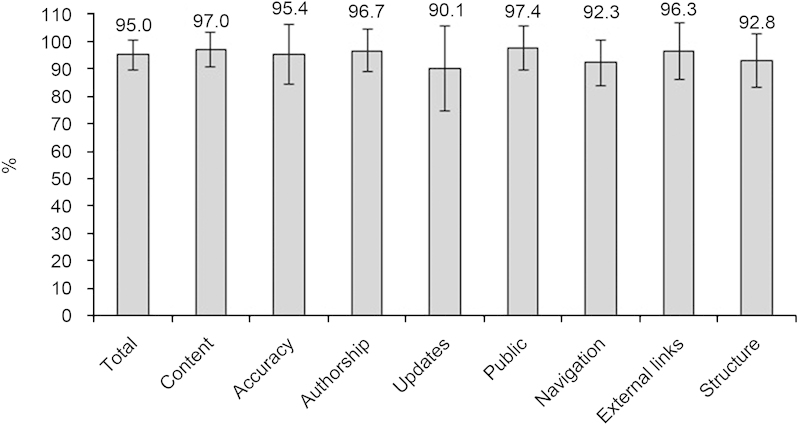

The score analysis by the Friedman test for each of these aspects in the Emory questionnaire (Fig. 2) showed significant differences between the subscales (chi-square = 86.96, less than 0.00). The post hoc analysis indicated that the navigation subscale score was significantly lower than the content, accuracy, authors, audience, and external links subscale scores. The structure subscale obtained significantly lower score than the authors, audience, and external links subscales. Finally, the updates subscale was significantly lower than the audience subscale.

Fig. 2.

Medium and standard deviation scores of each Emory questionnaire subscales and the total score (n = 109).

One of the study's purposes was to determine whether the analysis of technical content quality was similar among professionals working in different regions of Brazil. Regarding the technical quality, the Kruskal-Wallis test displayed no significant difference in the total score and Emory subscales between groups (Table 2).

Table 2. Medium and SD of the Emory questionnaire scores per region of practice and the Kruskal-Wallis test results (n = 109).

| Emory questionnaire | Region | Kruskal-Wallis test | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Southeast (n = 64) | South (n = 23) | NNM (n = 22) | ||||||

|

SD |

|

SD |

|

SD | k | p value | |

| Content | 97.9 | 4.45 | 96.0 | 7.05 | 95.4 | 8.85 | 2.08 | 0.35 |

| Precision | 96.5 | 9.83 | 93.5 | 11.22 | 94.3 | 13.21 | 2.15 | 0.33 |

| Authorship | 97.9 | 5.56 | 93.5 | 12.04 | 97.0 | 6.58 | 2.88 | 0.23 |

| Updates | 89.1 | 15.98 | 91.3 | 14.32 | 92.0 | 16.16 | 1.09 | 0.57 |

| Public | 98.2 | 5.84 | 95.7 | 10.40 | 97.2 | 10.86 | 1.01 | 0.60 |

| Navigation | 91.9 | 8.52 | 91.0 | 9.00 | 94.9 | 7.23 | 3.22 | 0.19 |

| Links | 96.9 | 9.21 | 96.4 | 10.61 | 94.7 | 13.74 | 0.25 | 0.98 |

| Structure | 94.5 | 7.41 | 90.1 | 9.05 | 90.9 | 14.44 | 4.71 | 0.09 |

| Total | 95.7 | 4.09 | 93.7 | 5.23 | 94.7 | 8.22 | 3.53 | 0.17 |

Abbreviation: NNM, North, Northeast, Midwest; SD, standard deviation.

There was a weak positive correlation between the time of professional experience and the accuracy subscale of the Emory questionnaire (Table 3).

Table 3. Correlation between time of experience and results from the Emory subscales and total score (n = 109).

| Emory questionnaire | Spearman correlation | |

|---|---|---|

| rho | p value | |

| Content | −0.07 | 0.41 |

| Precision | 0.22 | 0.02a |

| Authorship | 0.07 | 0.41 |

| Updates | 0.09 | 0.33 |

| Public | 0.10 | 0.26 |

| Navigation | −0.02 | 0.81 |

| Links | 0.07 | 0.41 |

| Structure | 0.05 | 0.57 |

| Total | 0.12 | 0.18 |

p < 0.05, statistically significant.

Regarding the website content evaluation (Table 4), the maximum score was equal to 5. It is noteworthy that 102 participants completed the content evaluation; however, some participants did not navigate through certain items in the Hearing Aid section, which was indicated by selection of the response option “did not access this part.” Thus, the number of participants varied according to the items.

Table 4. Descriptive analyses of the different items on the Babies' Portal website Hearing Aid section.

| Content | All participants | Group for statistical analysis (n = 71) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

SD |

|

SD | |

| What's a hearing aid? (n = 99) | 4.7 | 0.59 | 4.6 | 0.66 |

| Ear impression (n = 97) | 4.6 | 0.62 | 4.7 | 0.64 |

| Hearing aid types (n = 100) | 4.5 | 0.68 | 4.6 | 0.71 |

| Hearing aid technologies (n = 96) | 4.6 | 0.74 | 4.6 | 0.72 |

| The best HA for your child (n = 93) | 4.5 | 0.76 | 4.6 | 0.80 |

| Using one or two HAs (n = 94) | 4.7 | 0.57 | 4.7 | 0.61 |

| Hearing aid use and care (n = 96) | 4.7 | 0.59 | 4.7 | 0.65 |

| Hearing aid parts (n = 91) | 4.6 | 0.65 | 4.6 | 0.66 |

| Care with batteries (n = 90) | 4.6 | 0.59 | 4.7 | 0.61 |

| Hearing aid cleaning (n = 90) | 4.7 | 0.55 | 4.8 | 0.57 |

| Prevention of moisture (n = 90) | 4.7 | 0.56 | 4.8 | 0.60 |

| Earmold care (n = 91) | 4.6 | 0.60 | 4.7 | 0.62 |

| Turning the HA on and off (n = 87) | 4.7 | 0.55 | 4.8 | 0.59 |

| Earmold cleaning (n = 92) | 4.7 | 0.57 | 4.7 | 0.61 |

| Use of volume control (n = 91) | 4.7 | 0.60 | 4.7 | 0.60 |

| HA insertion and removal (n = 88) | 4.7 | 0.60 | 4.8 | 0.60 |

| Telephone use (n = 89) | 4.6 | 0.63 | 4.7 | 0.65 |

| Hearing aid troubleshooting (n = 90) | 4.6 | 0.61 | 4.7 | 0.63 |

| Creating a HA use routine (n = 89) | 4.7 | 0.59 | 4.8 | 0.59 |

| Tips for parents (n = 84) | 4.7 | 0.50 | 4.8 | 0.44 |

Abbreviations: HA, hearing aid, SD, standard deviation.

Statistical analysis with the Friedman test considered 71 participants who accessed and evaluated all the contents listed in the evaluation form (Table 4). There were significant differences between the contents mean scores (chi-square = 55.58 less than 0.00). Post hoc analysis indicated that this difference was found between the content on HA types and HA use and care.

The comparison of content assessment among participants working in different regions, performed by Kruskal-Wallis test, indicated significant differences in scores between the south and southeast regions in the best HA for a particular child, HA use and care, and HA insertion and removal items (Table 5).

Table 5. Medium and standard deviation scores of the website content per group of region and Kruskal-Wallis test results.

| Content | Region | Kruskal-Wallis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Southeast | South | NNM | ||||||

|

SD |

|

SD |

|

SD | k | p value | |

| What's a hearing aid? (n = 99) | 4.8 | 0.47 | 4.7 | 0.91 | 4.6 | 0.51 | 3.17 | 0.20 |

| Ear impression (n = 97) | 4.8 | 0.43 | 4.4 | 0.99 | 4.7 | 0.56 | 2.73 | 0.25 |

| Hearing aid types (n = 100) | 4.7 | 0.54 | 4.3 | 1.01 | 4.7 | 0.59 | 3.22 | 0.19 |

| Hearing aid technologies (n = 96) | 4.7 | 0.60 | 4.3 | 1.12 | 4.7 | 0.58 | 3.70 | 0.15 |

| The best HA for your child (n = 93) | 4.7 | 0.71 | 4.2 | 0.94 | 4.5 | 0.60 | 6.87 | 0.03a |

| Using one or two HAs (n = 94) | 4.8 | 0.36 | 4.6 | 0.94 | 4.6 | 0.50 | 5.06 | 0.07 |

| Hearing aid use and care (n = 96) | 4.8 | 0.40 | 4.6 | 0.97 | 4.5 | 0.51 | 5.70 | 0.05 |

| Hearing aid parts (n = 91) | 4.7 | 0.48 | 4.5 | 1.02 | 4.6 | 0.62 | 1.52 | 0.46 |

| Care with batteries (n = 90) | 4.8 | 0.41 | 4.4 | 0.96 | 4.6 | 0.49 | 4.15 | 0.12 |

| Hearing aid cleaning (n = 90) | 4.9 | 0.29 | 4.5 | 0.96 | 4.7 | 0.47 | 6.83 | 0.03a |

| Prevention of moisture (n = 90) | 4.9 | 0.34 | 4.6 | 0.98 | 4.6 | 0.50 | 4.84 | 0.08 |

| Earmold care (n = 91) | 4.8 | 0.46 | 4.6 | 0.96 | 4.6 | 0.51 | 3.64 | 0.16 |

| Turning the HA on and off (n = 87) | 4.9 | 0.34 | 4.5 | 1.01 | 4.8 | 0.45 | 3.06 | 0.21 |

| Earmold cleaning (n = 92) | 4.8 | 0.37 | 4.6 | 0.96 | 4.6 | 0.50 | 4.02 | 0.13 |

| Use of volume control (n = 91) | 4.8 | 0.46 | 4.5 | 1.01 | 4.6 | 0.49 | 1.51 | 0.46 |

| HA insertion and removal (n = 88) | 4.9 | 0.36 | 4.3 | 1.03 | 4.7 | 0.49 | 8.18 | 0.01a |

| Telephone use (n = 89) | 4.8 | 0.47 | 4.4 | 1.04 | 4.6 | 0.50 | 3.04 | 0.21 |

| Hearing aid troubleshooting (n = 90) | 4.8 | 0.43 | 4.6 | 0.96 | 4.5 | 0.61 | 4.25 | 0.11 |

| Creating a HA use routine (n = 89) | 4.8 | 0.41 | 4.6 | 0.96 | 4.6 | 0.61 | 0.69 | 0.70 |

| Tips for parents (n = 84) | 4.9 | 0.35 | 4.6 | 0.70 | 4.7 | 0.60 | 3.82 | 0.14 |

| Total (n = 102) | 95.7 | 6.59 | 90.7 | 16.52 | 92.6 | 8.28 | 5.75 | 0.05 |

Abbreviations: HA, hearing aid; SD, standard deviation.

p < 0.05, statistically significant.

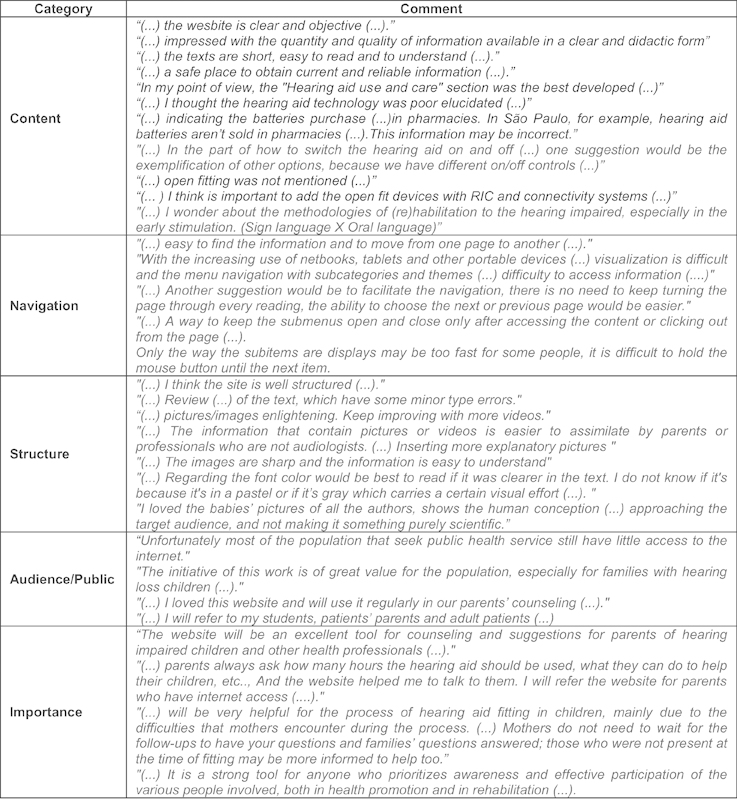

Thirty-eight professionals (34.9%) commented at the end of the questionnaires, and comments were grouped into different categories (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Professionals' comments.

Discussion

In this study, 80.7% (n = 88) of the participants accessed the Internet more than once a day. It corroborates with other studies that evaluated health professionals and demonstrated high levels of daily access from 54 to 77%.12 13

The vast majority of participants considered the subscales to be excellent (Fig. 1). More favorable ratings were obtained on the external links and content subscales. The external links subscale regards the relevance, timeliness, and operability and reliability of the links that are suggested by the website. Currently, the Babies' Portal website provides 20 external links that direct the user to governmental organizations, associations, and foundations that address aspects of accessibility and rights of people with disabilities. It was difficult to select other links regarding HA use and care in the Portuguese language that were detached from products and services' marketing. Regarding the content subscale, the participants agreed that the purpose of the Hearing Aid section of the Babies' Portal website was clear and discusses all aspects of the theme.

Fig. 1 shows that the most unfavorable score was assigned to the updates subscale. This subscale is composed of two items: clarity of the website publication date and frequent updates to cover the advances on this field. A detailed data analysis showed that 33 participants disagreed with the clarity of the website publication date; this was the strongest influence on the low score. The Babies' Portal website identifies the publication date and content updates on the homepage or sends it by e-mail to people registered in RSS. However, the result demonstrates the need to clearly identify the website's publication date updates because the lack of this data makes the user unsure about the information provided.14

Fig. 2 displays the mean scores for all the Emory subscales, which were all above 90%. The public subscale received better scores, demonstrating that the website was able to clearly identify to whom this tool was developed, which is essential for an electronic address.15 16 In this subscale, participants attributed high score on reading level appropriateness, information clarity, and usage of appropriate technical terms for the website target audience (i.e., parents of hearing-impaired children wearing HAs). The literature shows that information retention is linked to, among other aspects, the way the information is presented and the language used.17 18 Thus, the Babies' Portal website has the potential to increase information retention regarding HA.

The participants' comments (Table 1) also reflect the Hearing Aids section's adequacy for the target audience. Some participants suggested the application of this section to other audiences such as speech pathology and audiology graduate students and adult patients. It is noteworthy, however, that a participant expressed concern regarding difficulty accessing information linked to the Internet by public health system users.

Although the mean score difference between Emory subscales was small, it was significant in some cases. The navigation subscale obtained significantly lower score compared with the content (a difference of 4.7%), precision (a difference of 3.1%), authorship (4.4% difference), and public (5.1% difference) and external links (4% difference) scales.

The navigation subscale score was affected because the professionals indicated that the website needed a search engine. In fact, the Babies' Portal website provides a word search engine, which is located on the homepage and at the end of the menu information in other pages. The fact that professionals note the need of a search engine indicates that this mechanism may not be visible to users and this should be revaluated.

Participants also commented (Fig. 3) on repeatedly difficulty with the Babies' Portal website navigation, particularly regarding the menu functionality and internal links (hyperlinks) optimization. The Babies' Portal website is organized in primary, secondary, and tertiary menus, which all open or close when the mouse is hovered. Due to the volume of content available, the existence of a set menu (which remains opened when an item from the primary menu is accessed) could facilitate navigation; therefore, this is another revaluation required on the website.

Participants suggested the inclusion of previous and next page indicators to improve navigation. However, there is no hierarchy in content presentation in the Hearing Aids section, so the user can access the content in the order it best fits him or her.

The structure subscale obtained significantly lower score than the authorship (a difference of 3.9%) and public (a difference of 4.6%) and external links (3.5% difference) subscales. When the answer patterns of the questions that compose this subscale were analyzed, it was verified the low score was due to the items “The website usefulness does not decrease when using 'text only'—in this mode the pictures and videos are not displayed” (n = 19, 17.4%); “There are options for people with disabilities—to increase font size, audio files, etc.” (n = 22, 20.2%); and “If it isn't possible to access the audio and video from the website, the information provided would still be complete” (n = 22, 20.2%).

In the comments (Fig. 3), the participants also suggested changing the font color to enhance visualization and insert more animations.

The Babies' Portal website features the option to increase the font size to ensure readability.19 However, it does not alter the characters linked to images, videos, or animations, which may have influenced the assessment of this resource. The videos and animations do not have sound because they serve to complement the text. Also, there are no exclusive audio files on the website. Thus, it is necessary to restructure the Babies' Portal website to allow greater accessibility. This term, in the Internet context, is characterized by information flexibility and interaction relative to the presentation support. The flexibility should allow people with special needs to use the Internet, as well as in different environments and situations, through a variety of devices or browsers. The “Accessibility Recommendations for Web Content (WCAG) 2.0” was published by a working group that is part of the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) Web Accessibility Initiative,20 and it defines how to make Internet content more accessible to people with visual, auditory, physical, speech, cognitive, language, learning, and neurological disabilities. These recommendations also facilitate Internet use for the elderly, whose abilities are constantly changing due to the aging process, and facilitate the use for users in general. There was a tendency for the southern region to assign lower scores on most Emory subscales (Table 2); however, no significant differences were observed between the total and subscales scores by region. The data suggest that the technical quality aspects of the website were adequate to meet the characteristics and needs of different regions. However, it should be emphasized that there was a low adherence of the north, northeast and midwest, the reason these regions were grouped for results analysis. This is a limitation of this study, and therefore it is important to obtain data from a larger number of subjects in these regions.

One of the study's purposes was also to verify if the professional experience influences the website evaluation results. Correlations were very weak and nonsignificant between the time of practice and the Emory subscales (Table 3), except for the accuracy subscale, in which statistical significance was observed. However, this significance was due to an extreme value (outlier) in the data, while removing these outlier the “p” value was changed to no significant result (p > 0.05).

Table 4 shows the content average evaluation of all participants ranging from 4.5 to 4.7. This result is extremely favorable considering the maximum score (corresponding to very good) was equal to 5. On Table 5, it was verified that although the scores between items were quite similar, there was a statistically significant difference between the type of HA (4.6 points) and HA use and care (4.8 points) items.

Participants on their comments (Fig. 3) suggested that other content should be included in types of HAs items, such as open fit and receiver in the canal devices.

The American Academy of Audiology 2003 guideline for pediatric HA fitting indicates that HA physical characteristic selection is determined by the degree of hearing loss, external ear potential growth, and individual needs.21 In children up to 3 years old, target population in which the website was developed, the focus is on behind-the-ear HA fitting with custom earmold. This is because this HA type has a longer life (the circuit is not in direct contact with earwax) compared with custom HAs (in-the-ear ‐ ITE, in-the-canal ‐ ITC and completely-in-the-canal ‐ CIC), presents less risk of feedback (if it is provided with a proper earmold), and has alternative inputs (direct audio input, telecoil) that may be essential for assistive device coupling. For this reason the HA types content emphasizes mostly behind-the-ear devices and the earmold types that can be used in conjunction. Thus, custom device characteristics (used in older children) were addressed synthetically. Although it is not widely used in infants and small children, there is a need to discuss open-fit devices under the HA types because some manufactures have been inserting a specific segment of these devices on the market aimed at pediatric HA fitting.

One of the parents' greatest needs with hearing-impaired children in the initial HA fitting periods is information regarding the use and care of the HA and earmold.22 This finding led to the construction of the Hearing Aids section in the Babies' Portal website. For this reason, the largest and most detailed content of the section concentrates on use and care, which may have led to the highest score.

Table 5 displays the average content evaluation given by the regions ranging from 4.2 to 4.9. The southern professionals assigned lower scores for 11 of the 20 content evaluated. There were score differences between the southeast and south regarding the best HA for your child (0.5 difference), HA use and care (0.4 difference), and HA insertion and removal (0.6 difference) topics. There data should be analyzed cautiously due to the different number of participants between regions. In addition, there is intragroup variability verified in the SD, with the southern region scoring higher compared with the southeast region.

Also in Table 5, there was no difference in the total score between groups, suggesting that, in general, the Babies' Portal website contents are suitable for different regions. These data are important because the Babies' Portal website contents were developed based on perceptions and information needed of families living in the State of São Paulo. Given the differences in geographical, social, and economic development of the country, such contents could not meet the demands of other regions. Again, there is the need to have a larger number of participants in the north, northeast, and midwest for this to be evaluated separately.

Conclusion

The Babies' Portal website's Hearing Aid section was assessed as having an excellent technical quality according to Emory questionnaire scores. However, aspects such as website updates and navigability should be reviewed. The evaluations displayed that the website's technical aspects are appropriate for different regions and local practices.

The professionals considered the website content as being good or very good. There were differences in the best HA for your child, HA use and care, and HA insertion and removal topics between the south and southeast regions. Thus it is necessary to adequate these items to improve the Babies' Portal website.

The website was considered to have technical quality and content appropriate to complement the informative counseling to parents of hearing-impaired children using HAs.

References

- 1.Kurtzer-White E, Luterman D. Families and children with hearing loss: grief and coping. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2003;9(4):232–235. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.10085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fitzpatrick E, Angus D, Durieux-Smith A, Graham I D, Coyle D. Parents' needs following identification of childhood hearing loss. Am J Audiol. 2008;17(1):38–49. doi: 10.1044/1059-0889(2008/005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strömberg A. The crucial role of patient education in heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2005;7(3):363–369. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reed K Therapeutic Patient Education Available At: http://www.nz.reed-biomedical.com/library/pe_therapeutic.pdf5. Accessed January 29, 2010

- 5.Bastos B G, Ferrari D V. Internet e Educação ao Paciente. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;15(4):515–522. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mcdaid D Park A. Bupa health pulse 2010—online health: untangling the web. Available at: http://www.bupa.com.au/staticfiles/Bupa/HealthAndWellness/MediaFiles/PDF/LSE_Report_Online_Health.pdf5. Accessed October 22, 2012

- 7.Porter A, Edirippulige S. Parents of deaf children seeking hearing loss-related information on the internet: the Australian experience. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ. 2007;12(4):518–529. doi: 10.1093/deafed/enm009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guardiola-Wanden-Berghe R, Sanz-Valero J, Wanden-Berghe C. Quality assessment of the website for eating disorders: a systematic review of a pending challenge. Cien Saude Colet. 2012;17(9):2489–2497. doi: 10.1590/s1413-81232012000900029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Visser A, Deccache A, Bensing J. Patient education in Europe: united differences. Patient Educ Couns. 2001;44(1):1–5. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(01)00111-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laplante-Lévesque A, Pichora-Fuller M K, Gagné J P. Providing an internet-based audiological counselling programme to new hearing aid users: a qualitative study. Int J Audiol. 2006;45(12):697–706. doi: 10.1080/14992020600944408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Emory—University Rollins School of Public Health Health-Related Web Site Evaluation Form. 1998 Available at: http://www.sph.emory.edu/WELLNESS/instrument.html5. Accessed April 10, 2009

- 12.Kuosmanen L, Jakobsson T, Hyttinen J, Koivunen M, Välimäki M. Usability evaluation of a web-based patient information system for individuals with severe mental health problems. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66(12):2701–2710. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sommerhalder K, Abraham A, Zufferey M C, Barth J, Abel T. Internet information and medical consultations: experiences from patients' and physicians' perspectives. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;77(2):266–271. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silva L VER, Mello J F Jr, Mion O. Evaluation of Brazilian web site information on allergic rhinitis. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;71(5):590–597. doi: 10.1016/S1808-8694(15)31262-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eysenbach G, Köhler C. How do consumers search for and appraise health information on the World Wide Web? Qualitative study using focus groups, usability tests, and in-depth interviews. BMJ. 2002;324(7337):573–577. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7337.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sen P, Papesch M. Ménière disease patient information and support: which website? J Laryngol Otol. 2003;117(10):780–783. doi: 10.1258/002221503770716197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kessels R PC. Patients' memory for medical information. J R Soc Med. 2003;96(5):219–222. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.96.5.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nair E L, Cienkowski K M. The impact of health literacy on patient understanding of counseling and education materials. Int J Audiol. 2010;49(2):71–75. doi: 10.3109/14992020903280161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barboza E MF, Nunes E MA. A inteligibilidade dos websites governamentais brasileiros e o acesso para usuários com baixo nível de escolaridade. Incl Soc. 2007;2(2):19–33. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI) Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) Overview. 2011 Available at: http://www.w3.org/WAI/intro/wcag.php. Accessed January 28, 2011

- 21.American Academy of Audiology Pediatric Amplification Protocol. 2003. Available at: http://www.audiology.org/resources/documentlibrary/Documents/pedamp.pdf. Accessed January 28, 2011

- 22.Robbins A M. Empowering parents to help their newly diagnosed child gain communication skills. Hear J. 2002;55(11):55–59. [Google Scholar]