Abstract

Introduction

The midline thalamic nuclei are an important component of limbic seizures. Although the anatomic connections and excitatory influences of the midline thalamus are well known, its physiological role in limbic seizures is unclear. We examined the role of the midline thalamus on two circuits that are involved in limbic seizures: (a) the subiculum-prefrontal cortex (SB-PFC), and (b) the piriform cortex-entorhinal cortex (PC-EC).

Methods

Evoked field potentials for both circuits were obtained in anesthetized rats, and the likely direct monosynaptic and polysynaptic contributions to the responses were identified. Seizures were generated in both circuits by 20 Hz stimulus trains. Once stable seizures and evoked potentials were established, the midline thalamus was inactivated through an injection of the sodium channel blocker tetrodotoxin (TTX), and the effects on the evoked responses and seizures were analyzed.

Results

Inactivation of the midline thalamus suppressed seizures in both circuits. Seizure suppression was associated with a significant reduction in the late thalamic component but no significant change in the early direct monosynaptic component. Injections that did not suppress the seizures did not alter the evoked potentials.

Conclusions

Suppression of the late thalamic component of the evoked potential at the time of seizure suppression suggests that the thalamus facilitates seizure induction by extending the duration of excitatory drive through a divergent-convergent excitatory amplification system. This work may have broader implications for understanding signaling in the limbic system.

Keywords: seizure, epilepsy, limbic system, thalamus, mediodorsal nucleus, field potentials

Introduction

The midline thalamic nuclei have been implicated in a number of important functions associated with the limbic system, including learning and memory (Powell and Churchwell 2002, Mitchell et al. 2007, Cheng et al. 2010). They have also been shown to be critical in seizure activity in the limbic system (Cassidy and Gale 1998, Bertram et al. 2001, 2008). These thalamic nuclei, including the mediodorsal nucleus, are well placed to have a major role in many of the limbic system functions as they have extensive, overlapping, reciprocal connections to much of the limbic network (Ray et al. 1992, Van der Werf et al. 2002, Berendse and Groenewegen 1991, Hoover and Vertes 2007). However, the exact role of these connections in either limbic functions or limbic seizures is not known. As limbic functions and limbic seizures must operate within the confines of the same anatomical connections, a clear knowledge of the systemic influence of the midline thalamus on limbic system circuitry is required to understand its importance in either of those processes. Understanding of the influence of the midline thalamus may also add insight into the memory problems observed in temporal lobe epilepsy patients (Glowinski 1973, Viskontas et al. 2000, Voltzenlogel et al. 2006).

Because the thalamus receives afferents from many limbic regions, and sends strong, excitatory efferents to many of the same regions, a framework exists for an accessory excitatory pathway through the thalamus, a “divergent-convergent circuit”, capable of enhancing the direct region-to-region monosynaptic excitatory connections throughout the limbic network. Two such possible pathways are (a) the subiculum (SB) to the medial prefrontal cortex (PFC), and (b) the piriform cortex (PC) to the entorhinal cortex (EC). In both cases, there is a monosynaptic connection that forms the primary direct path as well as a secondary, disynaptic or polysynaptic connection through the thalamus (Jay and Witter 1991, Degenaitus et al. 2003, Kerr et al. 2007, Van de Werf et al. 2002). The pathway through the midline thalamus may provide additional excitatory input that has the potential to amplify the direct monosynaptic signal. In the normal brain, this secondary thalamic influence may assist in signaling related to learning and memory. During a seizure, this influence may help drive seizure activity in both pathways.

In this study, we hypothesized that the role of the medial dorsal thalamic region in limbic seizures is to provide increased excitatory drive through a divergent-convergent pathway from the induction site to the target To pursue that idea, we chose to study kindled limbic seizures as they provide a good means of determining whether a circuit manipulation is having an effect and how that manipulation may affect the circuit components. To evaluate the physiological influence of thalamic inputs on activity in the limbic circuits, we evoked field potentials from both SB-PFC and PC-EC pathways. We identified which components of these field potentials were influenced through polysynaptic pathways and then evaluated how these components changed with pharmacological inactivation of the thalamus. Our results suggest a role for the thalamus in initiating and spreading seizures in limbic circuits through divergent-convergent amplification of excitatory drive.

Materials and Methods

Animal Preparation and Electrode Placement

All animals were used in accordance with protocols approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Virginia. All stereotactic coordinates were derived from the rat brain atlas of Paxinos and Watson (1998). Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (250–300 g) were used for all experiments. The rats were kept on a standard 12 hour light dark cycle. To assure that potential endogenous diurnal fluctuations in system physiology did not influence the responses, experiments were performed at the same time every day, with the rats anesthetized mid morning and the studies completed by the mid afternoon.

Rats were anesthetized with urethane (1.2g/kg, i.p.) and monitored by regular noxious stimulation to the tail to ensure that they were maintained at a deep level of anesthesia. They were placed in a multi-armed stereotactic frame (Kopf Instruments, CA, USA). The skull was exposed and holes were drilled for electrode placement. Electrical stimulation was performed with bipolar, insulated, twisted pair stainless steel electrodes with tip diameter of 0.125mm and tip separation of 0.5–1 mm, and responses were recorded through a pulled glass micropipette with an approximate 1 MΩ tip resistance, filled with 0.9% saline and 1% Fast Green dye. The recording electrode was connected to the system through a silver-silver chloride wire. Following the experiment, the animal was killed while still under anesthesia and the brain was placed in 4.0% paraformaldehyde. Frozen sections confirmed electrode placements. Electrode positions were then correlated to the success of the experiment.

Electrode Placement: for Subiculum to Prefrontal Cortex (SB-PFC)

The subiculum has a monosynaptic connection to the medial prefrontal cortex, and there is a disynaptic pathway through the medial dorsal thalamic nucleus (Degentais et al., 2003: Mulder et al., 1997; Hoover and Vertes, 2007; Namura et al., 1994; Ray et al., 1994). A stimulating electrode was placed in the dorsal SB (from bregma, in mm): AP −6.3 to −7.0, ML 3.8 to 4.0, DV −2.5 to −3.0. The recording electrode was placed in the medial ipsilateral PFC: AP +2.7 to 3.2, ML 0.5, DV 2.0–3.5, 2.0° angle lateral to vertical (Figure 1A). The depth of the electrode, at the given angle, ensured that the electrode tip was well through the dorsal shallow layers of the cortex, where the field potentials reversed (Sloan and Bertram 2009).

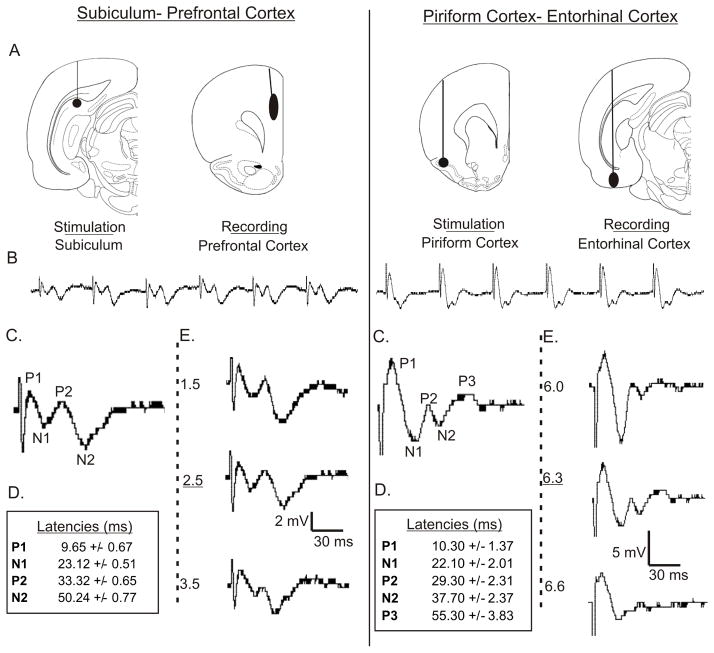

Figure 1. Evoked Potentials From Two Limbic Circuits.

(A) Electrode placement for SB-PFC and PC-EC responses (Brain section illustrations from Paxinos and Watson 1996). (B) Typical 120 ms i.s.i. train from the stimulation-recording pairs that shows the increasing amplitudes of the responses, plateauing by the 4th stimulation. (C) Typical 4th response from each train, with major peaks labeled. (D) Average latencies for each peak of the 4th responses. (E) Responses change with electrode depth. Position used in this study is underlined.

Electrode Placement: for Piriform Cortex to Entorhinal Cortex (PC-EC)

As mentioned in the introduction, the piriform cortex has a major monosynaptic input to the entorhinal cortex (Chapman and Racine, 1997). In addition, there is a multisynaptic pathway through the medial dorsal nucleus. The stimulating electrode was placed in the anterior PC: AP +1.8 to 2.5, ML 4.0 to 4.5, DV −6.5. The EC recording electrode was placed AP −6.8 to −7.3, ML 4.5 to 5.0, DV −6.3 to −7.0 (Figure 1A).

Electrode Placement: Thalamus

Stimulation or recording electrodes were placed in the ipsilateral mediodorsal nucleus: AP −1.8 to 2.3, ML 0.5, DV −4.8 to −5.5, 5.0° lateral to vertical.

Stimulation Protocols

Acquisition

Stimulus trains were delivered using a Winston timer connected to a constant-voltage stimulus isolation unit (SIU). Responses were recorded using an Axon Smartprobe connected to a Cyberamp. Responses were digitized at a rate of 10 kHz through a Digidata 1440 digitizer and analyzed using Axoscope 8.0 software (Molecular Devices, CA, USA). Responses were filtered with a lowpass filter of 1 kHz and highpass filter of 10 Hz.

Evoked responses

Because we are interested in the thalamic component of the evoked responses, it was necessary to ensure that we obtained a maximal response that resulted from activation of the mediodorsal nucleus. Because direct stimulation of the mediodorsal nucleus results in increasing response amplitudes in the target region with repeated stimulation (recruiting response) (Zhang and Bertram, 2002; Sloan and Bertram, 2009) we used a standard recruiting response stimulation protocol (Sloan and Bertram 2009, Dempsey and Morison 1942, Verzeano et al. 1953, Bazhenov et al. 1998). Stimulation consisted of 0.17 ms pulses at an interstimulation interval (i.s.i.) of 120 ms (~8.3 Hz). Responses were evoked by delivering stimulus trains to the SB, PC or thalamus. Five trains of six pulses were delivered and averaged with a ten second interval every ten minutes immediately before the induction of every afterdischarge. Electrode depths were adjusted to obtain maximal responses (Figure 1). Maximal responses (in which the overall amplitudes of all peaks were largest) were obtained by increasing stimulus intensity stepwise until the response amplitudes plateaued or until an intensity of 70V was reached (maximal current: 2.3 to 4.7 mA, at a typical stimulating electrode resistance of 15–30 kΩ). If the responses had not plateaued at 70V, or did not show the standard morphology, we found that one or both electrodes were off target and such data were discarded.

Measurements of evoked response amplitude and latency of the individual peaks were made with reference to the baseline prior to the stimulation pulse for amplitude and from onset of the stimulation pulse for latency. Because the thalamic component of the evoked potential increased with each repeated stimulation pulse before plateauing, all field potential measurements were made using the fourth stimulation. For the graphs in Figure 5, our analysis also included the differences in amplitudes between peaks within the waveform as a means of comparing changes in early and late components. Statistical analyses were performed using SigmaStat 3.0 software. Differences in average amplitudes and latencies before and after TTX injection, as well as LTP-induced changes, were compared using paired t-test, while comparisons of amplitude differences between early and late components used Student’s t-test. Significance was set at the p<.05 level.

Figure 5. Limbic Seizures Affected by TTX in Midline Thalamus.

(A) Limbic seizure afterdischarges before and after injection of TTX into the midline thalamus. Note that seizure activity is greatly reduced with TTX injection in both sets of responses. (B.) Average seizure durations before, during and after TTX with subsequent recovery. (C) Five-second samples from each trace (the boxed area on the full traces).

Seizure Induction

Afterdischarges were elicited by a 20Hz train consisting of monophasic pulses of 0.17 ms duration for five seconds at the same intensity that was used for the evoked potentials (range 50–70V, up to 4.7 mA). Stimuli were given at standard ten minute intervals immediately following each evoked response stimulus session. Afterdischarges were identified as large, continuous spike bursts beginning at the end of the stimulus. Afterdischarge termination was determined by the end of the last regularly occurring spike burst. For each experiment, a minimum of ten stimulus trains were required to induce afterdischarges of a consistent duration. A stable afterdischarge duration was defined as a minimum of three afterdischarges of consistent duration of a minimum of 10 seconds with less than 30% variation between them. This seizure induction method allows for consistent and stable afterdischarge durations that provide a good platform for evaluating the effects of pharmacologic manipulation of the circuit components.

Identification of Components of Evoked Potentials

Because these field potentials are complex evoked responses that are composed of post-synaptic potentials that are driven by mono-, di- and polysynaptic sources, it is necessary to estimate the likely time windows in which different inputs are likely to have their contribution to the overall field potential.

Input/Output Protocol

As monosynaptic components of a field response are more likely to appear at lower stimulation intensities that are those from multisynaptic pathways, we performed an input/output protocol to determine which waveform components appeared at lower stimulation intensities, and which appeared as the stimulation intensities were increased. The stimulations were initiated with a train of 10V pulses with 5 trains averaged per intensity. The intensity was increased stepwise by 10V (0.33 mA) until a plateau was achieved, or to a maximum of 70V (4.3 mA). This protocol ensured that maximal responses were obtained for each animal.

Long-term potentiation (LTP)

Because LTP is generally considered primarily monosynaptic, we induced LTP in both circuits to help determine which components were more likely monosynaptic. Although LTP is possible through a disynaptic system if the intermediate regions are susceptible to LTP, it is usually apparent with high stimulation intensities and at longer latencies. Polysynaptic responses affected by LTP will appear late in the overall response and will not obscure the early responses from monosynaptic connections. We used previously established protocols (Laroche et al 1990, Degenetais et al. 2003, Kawashima et al. 2006) Recordings of two pulses (120 i.s.i.) were made every three minutes at 50% of the maximal stimulus intensity. LTP induction was achieved through 12 bursts of 200 Hz trains at maximum voltage, with each train lasting for 250 ms with a 1 second inter-train interval. Two LTP induction sessions were applied, with ten minutes rest between them. Recordings were continued every three minutes for a half-hour following the second train, after which pulses were recorded every five minutes for another twenty minutes. A minimum of five trains, with a ten second inter interval between trains, was averaged for each recording. We analyzed the significant peaks, early and late, to determine which ones had changed and how. The short trains and sub-maximal stimulations were used in order to isolate the monosynaptic components and reduce polysynaptic components as much as possible.

Polysynaptic Component Construct

To identify a minimum latency for the thalamic polysynaptic component to appear in the field potentials, we recorded from two points in the potential disynaptic pathway in both circuits (e.g., SB-Thalamus and Thalamus-PFC and PC-thalamus and thalamus-EC) and used these data to estimate a potential time window (earliest likely time of occurrence) for a contribution of a disynaptic response from the thalamic pathway. By temporally aligning the responses from the two sequential pathways in and out of the medial dorsal nucleus, we estimated an approximate minimum latency for thalamic involvement in our evoked potentials.

TTX Drug Delivery

Prior to injection of the sodium channel blocker TTX, all animals had to have a baseline seizure duration and evoked potential morphology, as described above, that was consistent for 30 minutes after the placement of the canula into the thalamus, but prior to injection.

To deliver drugs to the thalamus, a 25 ul Hamilton syringe was loaded with either 0.1 mM tetrodotoxin (TTX) or 0.9% saline solution for vehicle control. The tip of the syringe was placed into the ipsilateral mediodorsal nucleus (AP −1.8 to 2.3, ML 0.5, DV −4.8 to 5.5, 2.0° medial to vertical). Confirmation of canula placement was included during confirmation of electrode placement. Previous work has shown that injections of TTX outside of the midline thalamic nuclei have no effect on seizures, so proper placement was judged initially by seizure suppression. A rest period of ten minutes was allowed after the injection prior to resuming stimulations to permit sufficient spread of the drug and to minimize the possibility of mechanical effects from the injection. The standard TTX injection was 0.75 μl (0.1 mM), released slowly over three minutes. An effect seen only after 20 minutes post-injection was interpreted as being an injection outside of the target zone. Seizure suppression persisted for 40 to 80 minutes before recovering. Seizure duration had to be reduced by 75% from baseline for longer than 20 minutes to be considered a successful suppression.

Electrode or cannulas that were found outside the target regions were included in a separate analysis from those inside the region to determine the site specificity of these experimental manipulations.

Results

Evoked Field Potentials

Trains of evoked potentials with consistent morphologies were recorded from both the Subiculum to Prefrontal Cortex (SB-PFC) (n=6) and Piriform Cortex to Entorhinal Cortex (PC-EC) (n=5) circuits (Figure 1). Because the morphology of the waveforms varied by recording depth, electrodes were adjusted to ensure a standard morphology of the responses (Figure 1E). The average depth of recordings used in the PFC was 2.5 +/− 0.5 mm, and the average depth used in the EC was 6.3 +/− 0.3 mm.

Both sets of field potentials were complex, containing multiple positive and negative peaks at maximal stimulus intensity. Amplitudes of all peaks increased between the 1st and 4th stimulation of the train. The 4th stimulation of the train was used for analysis because all peak amplitudes had plateaued by that point, and because the likelihood of a disynaptic pathway through the thalamus being incorporated into the response was increased (see Methods). In the case of the SB-PFC responses, the responses consisted of two positive (P1 and P2) and two negative (N1 and N2) waves. In the case of the PC-EC circuit, the field potential included a 3rd positive wave (P3).

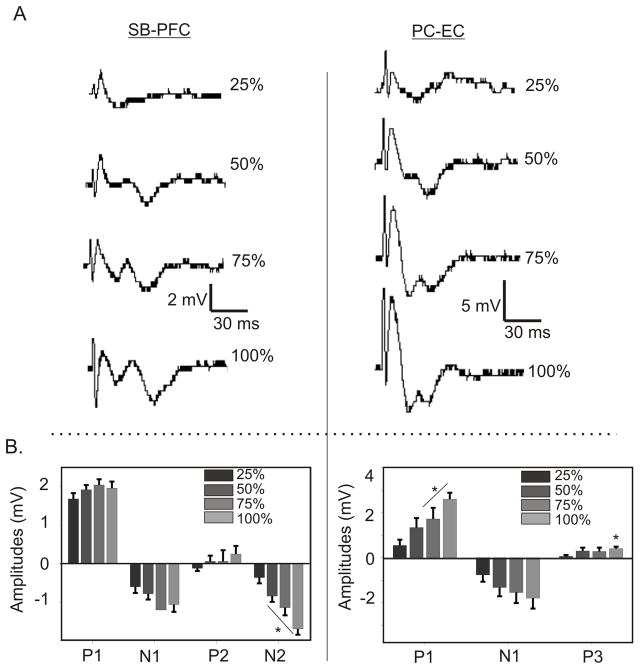

When stimulus intensity was increased stepwise, all peaks in the responses from both circuits increased in amplitude with stronger stimulus intensities (Figure 2). In the SB-PFC responses, P1 did not change significantly, and N1 plateaued by the time it reached 75% stimulation. P2 and N2 did not plateau until the max stimulation. In the PC-EC, the P1, N1 and P3 increased significantly in amplitude until they plateaued at max stimulation. Maximal stimulus intensities were used to ensure that all peaks were present at their maximum amplitudes.

Figure 2. Effect of Increased Stimulation on Evoked Responses.

To define maximal responses, as well as to determine the relative stimulus intensity needed to elicit each wave in the responses of both SB-PFC and PC-EC circuits, stimulus intensity was increased stepwise until maximum response. (A) Change of morphology and peak onset as intensities are increased, by increments of 25% of maximal stimulation. Note that responses at 50% intensity are different than those at 100%, and that all peaks are fully formed at maximum intensity. (B) Average peak amplitudes as intensities are increased. (* P< .05 by student’s t-test compared to 25% intensity).

Confirmation of Early Monosynaptic Component: LTP

Prior to attempting to isolate polysynaptic components through the thalamus, the monosynaptic components had to be identified. The changes that occurred in the responses as stimulus intensities were increased, in which earlier peaks required less intensity then later peaks, suggested that earlier peaks are more likely to represent direct monosynaptic inputs(Figure 2). To obtain further evidence that the early components represented a monosynaptic connection, we used long-term potentiation (LTP), which is generally considered to be a predominantly monosynaptic phenomenon.

In order to minimize the influence of a potential thalamic recruiting response or LTP effects through polysynaptic circuits, we stimulated at half-maximal intensity and reduced the stimulus train to a paired pulse. Because of these changes in stimulation parameters, the responses were less robust compared to the maximal multiple pulse stimulus train responses. The 2nd response of the pair was evaluated for the potential effect of the potentiating stimulation. We emphasize that peak latencies in these responses, due to the low stimulation intensity and the lack of a train, are not precise correlates to peaks from the control responses described (see Figure 2 for differences between maximal and half-maximal stimulations).

The LTP protocol caused an increase in peak amplitudes in both sets of responses (Figure 3). In the SB-PFC circuit (n=5), at half-maximal stimulation, the N1 with a latency of 21 ms increased in amplitude by approximately 100% after potentiation (Figure 3) and didn’t change for the duration of the experiment (35 min). In the PC-EC circuit (n=7), the N2 at a latency of 32 ms increased by approximately 40% (Figure 3B) and held for the duration of the experiment. Both of these peaks occur within the range considered to form the “early” component of the response, and the experiment suggests that these peaks primarily represent the monosynaptic input. The lack of change in P1 in both circuits suggests that the peak may represent an axon volley, rather than a synaptic response. The effect of the LTP protocol and the latencies of the affected peaks correlate with previous findings in these circuits (Laroche et al. 1990, Degenetais et al. 2003, Kawashima et al. 2006, Hamam et al. 2007).

Figure 3. Long-Term Potentiation in Both Circuits Identifies Early Monosynaptic Component.

(A) 2nd responses from paired pulses in both pathways, taken at half-maximal intensity, before and after LTP was induced. Because of the low stimulation intensity, the peaks shown are not directly comparable to those in Figure 1. An overlay of the waveforms shows that the first primary negative wave has increased in amplitude. (B) Amplitudes of the positive and negative peaks. In both cases, the negative peak increases significantly (* P< .05 by student’s t-test). (C) Changes in the amplitude of the negative peak over the course of the experiment. Note the rise in amplitude after the LTP stimuli were given. The latency of these peaks occurs earlier than the probable thalamic component of the response, and fall within the range of the monosynaptic component (see Figure 4).

Composition of Field Potentials

In order to estimate approximate time windows for the appearance of a possible thalamic component to the overall responses, we needed to identify the minimum time required for thalamically-mediated post-synaptic potential to appear.

To determine a minimum latency for a signal passing through the thalamus, we recorded evoked responses in the medial dorsal nucleus after stimulation in either the SB or PC. We also stimulated in the mediodorsal nucleus and recorded in the PFC or EC. We then combined the two sets of data to estimate the transit time of a signal from the primary stimulation site (SB or PC) through the thalamus and from the thalamus to the recording site in a circuit that includes at least two synapses. Responses were generated by single stimulations. The first peak occurring after 6 ms in each of the responses was used for the alignment. The results of this alignment are shown in Figure 3.

For SB-Thal-PFC disynaptic pathway

Subiculum to Thalamus: Responses were of low amplitude, consisting of a sharp early peak, and then a larger negative peak which recovers to baseline. Thalamus to Prefrontal Cortex: Responses have one primary peak, sometimes followed by a secondary peak, followed by a recovery. These responses are large, and, when stimulated in a train, would greatly increase in amplitude over the course of a train (Bertram and Sloan 2009).

For PC-Thal-EC disynaptic circuit

Piriform Cortex to Thalamus: Responses begin with a short negative, followed by a positive peak, followed by a negative wave that recovers. Thalamus to Entorhinal Cortex: This response consists of a sharp early peak, a small negative peak, a large positive peak and a deep negative wave that recovers gradually. The early peak is probably an axonal volley.

By adding the latencies of the first peak in each recording in the disynaptic pathway, we came to an estimated minimum latency for a thalamic component to appear in the primary recording site, as shown in Figure 4. These results, combined with the LTP and stimulus intensity results (in which a greater stimulus intensity was required to generate later peaks), as well as the thalamus-like augmentation of late responses over the course of the train, we considered the “early” component of the responses (before 35 ms) to primarily contain the monosynaptic direct signal and the “late” component (after 35 ms) to be multisynaptic and to contain the contribution of the thalamus.

Figure 4. Estimation of Onset of Thalamic Component.

To determine the approximate minimum time for the appearance for thalamic influence responses in the (A) SB-PFC and (B) PC-EC pathways, responses from the initiating site to the thalamus and the from the thalamus to the target site were obtained. Responses are aligned (1–3) and their latencies added to arrive at a minimum latency for thalamic involvement. The first major peak is treated as the monosynaptic response. The gradient bar (4) beneath the direct responses is placed to suggest that the onset of polysynaptic components occurs gradually within that suggested timeframe. The individual and combined latencies are quantified in the table inset. This figure is to be used and interpreted as a guide, and not an exact demonstration of thalamic influence in the direct response.

Seizures and Effect of Thalamic Inactivation

Seizure afterdischarges were reliably induced from both initiating sites by 20Hz stimulations (Figure 5). Afterdisharges were defined as repetitive bursts of spikes, and termination was determined after the last regular burst discharge followed by suppression of the EEG amplitude compared to the prestimulation baseline and was defined as the interval between the end of stimulation and the end of the last burst discharge. Baseline afterdischarge durations were between 15 and 25 seconds for both circuits, although PC-induced seizures tended to be shorter than those induced in the SB.

Injection of TTX into the midline thalamus caused a reduction or complete suppression of seizure activity in both circuits (Figure 5). A seizure was considered suppressed when the seizure duration was reduced by at least 70% from the baseline duration for at least 30 minutes. The effect of the drug lasted, on average, 40–80 minutes, during which the seizures gradually recovered. This process of seizure reduction and recovery has been demonstrated previously (Cassidy and Gale 1998, Bertram et al. 2008). We considered a successful reduction in seizure activity as a marker indicating that the cannula was correctly placed in the thalamus and that inactivation of the thalamus was successful. Injections of saline in the mediodorsal nucleus showed a brief effect on field potentials, but this effect never lasted longer than ten minutes. Out of target injections caused no change in either seizure duration or evoked potentials (Figure 7B).

Figure 7. Position Specificity of Effect of TTX on Seizures and Evoked Potentials.

To show that the effects shown are specific to TTX injections in the mediodorsal nucleus, injections within and without that region are compared. (A) Both effective (filled circles) and ineffective (open circles) injections of TTX into the area of the midline thalamus are shown for both SB-PFC and PC-EC pathways. (Brain section illustrations from Paxinos and Watson 1996). (B) Sample seizure from an ineffective injection outside of the mediodorsal nucleus, showing a seizure before injection, and 30 minutes post injection. No change is duration is seen. (C) Evoked responses corresponding to the seizures shown, with no change seen. (D) Summary of average seizure durations and evoked potential peak amplitudes in both sets of animals with injections outside the MD (n=5 for SB-PFC, n=6 for PC-EC).

Effects of Thalamic Inactivation on Evoked Potentials

All injections of TTX into the midline thalamus that were sufficient to cause a reduction of seizure activity also altered evoked field potentials in both circuits, particularly in the late components in both sets of responses (Figure 6). In the case of the SB-PFC circuit, all peaks except P1 were affected by the drug, but peaks in the late component were the most significantly reduced (Late component, N2-P2, reduced from 1.94 +/− 0.30 mV to 0.50 +/− 0.10 mV). In the case of the PC-EC circuit, the P3 peak was significantly reduced, while the other peaks remained close to control levels (P3 reduced from 1.44 +/− 0.25 mV to 0.30 +/− 0.13 mV). Latencies remained similar to control measurements. Injection of TTX outside of the borders of the mediodorsal nucleus did not yield any changes to seizure duration or evoked potential amplitudes (Figure 7C). Changes to the evoked responses persisted for the same amount of time as seizure suppression, and recovered as seizures recovered.

Figure 6. Evoked Potentials Affected by TTX in Midline Thalamus.

(A) Sample averaged responses are shown for the SB-PFC (n=6) and PC-EC (n=5) circuits (3rd and 4th stimulations), before injection of TTX into the midline thalamus, after injection and after recovery. In both cases, the late component of the response is reduced in amplitude, and then recovers. (B) Amplitude differences between the peaks in the early (P1-N1) and late (P2-N2 in SB-PFC, P3-Baseline for PC-EC) components of the waveforms from the 4th stimulation in both pathways, and how they change with TTX injection in the thalamus. In both cases, the changes in the late components of the response are significantly reduced. *P<.05 by paired t-test.

Discussion

In this paper, we used a combination of evoked field potentials and kindled seizures in two different limbic pathways to evaluate the role of the thalamus in limbic seizures. Evoked potentials were reliably obtained by stimulating in the subiculum or piriform cortex and recording in the prefrontal or entorhinal corticies, respectively. Both pathways had direct, monosynaptic connections as well as a potential indirect, polysynaptic pathway through the thalamus. Pharmacological blockade of the mediodorsal nucleus of the thalamus suppressed seizures generated in both pathways, and concurrently reduced the late polysynaptic components of the evoked potentials. That the loss of the polysynaptic pathway through the thalamus is associated with attenuated seizure activity and loss of the late component of the field potentials suggests that thalamically-mediated excitation may provide an additional excitatory drive that prolongs the duration of excitation.

The thalamus has pathways that may be critical in facilitating communication between different regions throughout the brain. A divergent-convergent (D-C) circuit is one in which two pathways emerge from a starting point and reconvene at the same target. Although the functional value of the D-C circuits discussed has not yet been established, they have the potential to prolong depolarization at the target by sending two time-staggered excitatory signals, thereby amplifying the signal. For example, in sensory cortex, afferent neurons extending from layer V have been shown to drive a circuit through the thalamus that will reinforce direct cortical-cortical signals to other cortical regions (Reichova and Sherman 2004, Llano and Sherman 2009, Theyel et al. 2010). In a theoretical neural network, a D-C circuit can prolong the initial depolarization from a direct monosynaptic signal, thereby amplifying and prolonging the total period of excitation. Although such means of extending the period of excitation on a neuron may be important for some forms of normal function, the same prolonged excitation from a D-C circuit may induce pathological states such as seizures. Furthermore, focal or regional seizure activity that would not be intense enough to spread out to other limbic structures may be reinforced by the D-C excitatory amplification through the thalamus, thus permitting the recruitment of other structures. A simple model of how these D-C circuits may be constructed in the limbic network and how they may function in seizure activity is presented in Figure 8. That such circuitry may be key to seizure spread is not a new idea; thalamocortical circuits have been shown to be centrally involved in generalized seizures (Avoli and Gloor 1982, Kostopolous 2001, Meeren et al. 2002, Meeren et al. 2009). However, the exact role they may play in limbic seizures has not been clear until now.

Figure 8. Representation of Divergent-Convergent Excitatory Circuits in the Limbic System.

Model of a proposed role for the thalamus in limbic seizure circuits. A seizure is initiated in a region in the network (focus). Excitatory activity affects signaling to all the monosynaptic afferent targets of the region, including the midline thalamus. The thalamus, in turn, sends an additional, excitatory signal to all of the monosynaptic targets of the focus. This additional excitation assists in recruiting and driving the target structures into seizure activity by prolonged excitation.

The anatomic connections that form the basis of the two D-C limbic circuits used in this study, and which give rise to the evoked potentials shown, are well known. Subiculum and CA1 efferents exit from its shallow layers (alveus), through the fimbria, fornix and lateral septum to the medial prefrontal, most strongly innervating the infralimbic and prelimbic regions. (Swanson 1981, Jay and Witter 1991, Degenaitus et al. 2003) Subicular afferents also travel to the midline thalamus (Herkenham 1978, Namura et al. 1994 McKenna and Vertes, 2004, Cavdar et al. 2008). All midline thalamic nuclei, including the mediodorsal nucleus, innervate the medial PFC, with each midline thalamic nucleus overlapping its target fields in the PFC with the others. These thalamic afferents are excitatory (Van der Werf et al. 2002, Berendse and Groenewegen 1991, McFarland and Haber 2002, Hoover and Vertes 2007).

The shallow layers (II and III) of the piriform cortex project to the superficial layers of the medial and lateral entorhinal cortices, as well as to the mediodorsal nucleus (Cornwall and Phillipson 1988, Chapman and Racine 1997, Kerr et al. 2007). Several midline nuclei, including the paraventricular, parataneial and reuniens as well as the mediodorsal send excitatory projections to the both the medial and lateral EC (Van de Werf et al. 2002, Kerr et al. 2007). Stimulation of the mediodorsal has been shown to elicit excitatory potentials in the EC (Zhang and Bertram 2002). Both structures are considered susceptible to and participants in limbic seizure activity (McIntyre and Gilby, 2008).

There are other factors that must be considered in the interpretation of our results. First, while the TTX injections were placed directly into the midline thalamus, and the injection sites were verified visually, the proximity of the midline thalamus to a number of fiber tracts raises the possibility that the drug could have exerted its effect by blocking conduction of other pathways that pass near the injection site. Although this confounding factor cannot be completely excluded, the observation that injections outside of the mediodorsal nucleus had no effect on the seizures or the evoked potentials make this explanation less likely. The specificity of the injection site is further emphasized when noting that even injections into the reuniens nucleus, which also connects to the PFC and hippocampus, did not have an effect in this study.

The complex nature of the waveforms, as well as the tightly interconnected nature of the limbic network, suggests that multiple afferent pathways could contribute to the multiple evoked potential components in both pathways. Because of the potential contribution to the response from other sites that would likely appear around the same time as the thalamic component, we cannot say with any certainty that the late component is exclusively thalamic in origin. These peaks consist of multiple signal sources, including distant and local synaptic activity, as well as afferent fiber volleys and possibly population spikes. However, the observation that the late component changes with inactivation of the thalamus strongly suggests that a significant part of that component is from the thalamus. Although ideally we would like to identify each component with regards to its source and nature (depolarizing or hyperpolarizing), the complexities of such an analysis beyond a single monosynaptic response rapidly become prohibitive without lesioning or inactivating all but the single potential source of interest. Measuring shifts in unit potential frequency has been used to estimate when post-synaptic potentials were excitatory or inhibitory (increase or decrease in frequency, respectively). Although examining unit potentials could tell us when there was increased excitatory activity, it would not tell us the source. We have demonstrated previously that the thalamic input to these two cortical sites (as well as to others) is excitatory (Sloan and Bertram 2009, Zhang and Bertram 2002), but we can’t determine when, precisely, this activity would arrive through a polysynaptic pathway. We are left with creating a likely time window and determining whether the responses in that window change with manipulation of the mediodorsal nucleus.

One structure that must be mentioned in having a potential role in these results is the reticular nucleus of the thalamus (nRT). The nRT is the major inhibitory inputs to this region, and receives reciprocal connections from various cortical sites, including those studied here. In a seizure, or in a stimulus train, it is likely that the nRT becomes involved. In these experiments, the main target of the nRT (the thalamus) is being effectively removed, and therefore, so is the direct action of the nRT. This inevitable contribution of the nRT, among the other inputs and outputs cited, should be a focus in future work to understand how the crucial role of the thalamus in limbic seizures is modulated in the complete system.

This study suggests that limbic seizures initiate and spread through the enhanced excitation of D-C excitatory pathways, specifically those that pass through the midline thalamus. Although the monosynaptic path from the stimulus site to the target site induces a normal excitatory response, it is the additive contribution of the later-arriving multisynaptic thalamic excitatory drive, prolonging the monosynaptic excitation that may be necessary to drive the network into a seizure. This possible role for the thalamus supports the theory that limbic epilepsies, in general, evolve in a hyperexcitable limbic network in which any structure within the network can act as the initiating site of a seizure (Bertram 1997, 2009, Bertram et al. 1998).

Although the focus of this study is the role of the midline thalamus in seizure activity, there are broader implications for this work in understanding the normal function of the thalamus in communication between cortical and subcortical structures. For example, Lopez et al. recently suggested that the role of the thalamus in hippocampal-PFC communication may be important for remote spatial memory processing (Lopez et al. 2009), contributing to one of the many roles that the hippocampal-PFC pathway is thought to play in memory (Laroche et al. 1990, Muldor et al. 1997, Degenetais et al. 2003, Kawashima et al. 2006). Furthermore, Van der Werf and colleagues (2003) suggested that the general role of the midline nuclei in declarative memory is to help focus on important information with regards to the contents and state of memory processes. Morales et al. have submitted evidence that the midline thalamus has a physiological role in the memory functions subserved by the hippocampus/PFC connection (Morales et. al. 2007). The possible role of the thalamus in PC-EC communication has been studied less, although it may be posited that the thalamus assists with the communication of important primary olfactory information for application in memory processes (Kerr et al. 2007, Dickerson and Eichenbaum 2010). Our results suggest that, in studying the role of the thalamus in cortico-cortical or subcortical communication, the strong influence of divergent-convergent excitatory circuitry through the thalamus should not be ignored.

In conclusion, the thalamus may serve to amplify excitatory input between limbic structures, and this ability may be an essential component of an enhanced excitatory drive necessary to drive limbic seizure activity.

Research highlights.

We examine the role of the midline thalamic region in limbic seizures. There are data suggesting that the midline thalamus has a major role in limbic seizures. Inactivation of this region with tetrodotoxin inhibits limbic seizures induced by electrical stimulation of limbic sites. We demonstrate that tetrodotoxin in the medial dorsal nucleus blocks seizures and reduces the thalamic component of the evoked responses. Findings suggest that medial dorsal nucleus’s role is to prolong excitatory drive as part of a divergent-convergent circuit.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by in part by NIH grant: NS25605 and NS064438. We thank John Williamson for his technical support.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Avoli M, Gloor P. Interaction of cortex and thalamus in spike and wave discharges of feline generalized penicillin epilepsy. Exp Neurol. 1982;76:196–217. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(82)90112-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazhenov M, Timofeev I, Steriade M, Sejnowski TJ. Cellular and network models of for intrathalamic augmenting responses during 10 Hz. stimulation. J Neurophysiol. 1998;79:2730–2748. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.5.2730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berendse HW, Groenewegen HJ. Restricted cortical termination fields of the midline and intralaminar thalamic nuclei in the rat. Neuroscience. 1991;42:73–102. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(91)90151-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertram EH. Functional anatomy of spontaneous seizures in a rat model of limbic epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1997;38:95–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1997.tb01083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertram EH, Zhang DX, Mangan P, Fountain N, Rempe D. Functional anatomy of limbic epilepsy: a proposal for central synchronization of a diffusely hyperexcitable network. Epilepsy Res. 1998;32:194–205. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(98)00051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertram EH, Mangan PS, Zhang DX, Scott CA, Williamson JW. The midline thalamus: alterations and a potential role in limbic epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2001;42:967–978. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2001.042008967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertram EH, Zhang D, Williamson JW. Multiple roles of midline dorsal thalamic nuclei in induction and spread of limbic seizures. Epilepsia. 2008;49:256–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy RM, Gale K. Mediodorsal thalamus plays a critical role in the development of limbic motor seizures. J Neurosci. 1998;18:9002–9008. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-21-09002.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavdar S, Onat FY, Cakmak YO, Yananli HR, Gulcebi M, Aker R. The pathways connecting the hippocampal formation, the thalamic reuniens nucleus and the thalamic reticular nucleus in the rat. J Anat. 2008;212:249–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2008.00858.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman CA, Racine R. Converging inputs to the entorhinal cortex from the piriform cortex and medial septum: facilitation and current source density analysis. J Neurophys. 1997;78:2602–2615. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.5.2602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H, Tian Y, Hu P, Wang J, Wang K. Time-based prospective memory impairment in patients with thalamic stroke. Behav Neuro. 2010;124:152–158. doi: 10.1037/a0018306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornwall J, Phillipson OT. Afferent projections to the dorsal thalamus of the rat as shown by retrograde lectic transport: I. The mediodorsal nucleus. Neuroscience. 1988;24:1035–1049. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(88)90085-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenetais E, Thierry AM, Glowinski J, Gioanni Y. Synaptic influence of hippocampus on pyramidal cells of the rat prefrontal cortex: an in vivo intracellular recording study. Cerebral Cortex. 2003;13:782–792. doi: 10.1093/cercor/13.7.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey EW, Morison RS. The electrical activity of the thalamic relay system. Am J Phys. 1942;138:283–291. [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson BC, Eichenbaum H. The episodic memory system: neurocircuitry and disorders. Neuropsychopharm. 2010;35:86–104. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glowinski H. Cognitive deficits in temporal lobe epilepsy. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1973;157:120–137. doi: 10.1097/00005053-197308000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamam BN, Sinai M, Poirier G, Chapman CA. Cholinergic suppression of excitatory synaptic responses in layer II of the medial entorhinal cortex. Hippocampus. 1982;17:103–113. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herkenham M. The connections of the nucleus reuniens thalami: evidence for a direct thalamo-hippocampal pathway in the rat. J Comp Neuro. 1978;177:589–610. doi: 10.1002/cne.901770405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoover WB, Vertes RP. Anatomical analysis of anatomic projections to the medial prefrontal cortex of the rat. Brain Struct Funct. 2007;212:149–179. doi: 10.1007/s00429-007-0150-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laroche S, Jay TM, Thierry AM. Long-term potentiation in the prefrontal cortex following stimulation of the hippocampal CA1/subicular region. Neurosci Letters. 1990;114:184–190. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90069-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llano DA, Sherman SM. Differences in intrinsic properties and local network connectivity of identified layer 5 and 6 adult mouse auditory cotricothalamic neurons support a dual corticothalamic projection hypothesis. Cerebral Cortex. 2009;19:2810–2826. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez J, Wolff M, Lecourtier L, Cosquer B, Bontempi B, Dalrymple-Alford J, Cassel J-C. The intralaminar thalamic nuclei contribute to remote spatial memory. J Neurosci. 2009;29:3302–3306. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5576-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawashima H, Yoshinori I, Grace AA, Takita M. Cooperativity between hippocampal-prefrontal short term plasticity through associative long-term potentiation. Brain Res. 2006;1109:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr KM, Agster KL, Furtak SC, Burwell RD. Functional neuroanatomy of the parahippocampal region: the lateral and medial entorhinal areas. Hippocampus. 2007;17:697–708. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostopolous GK. Involvement of the thalamocortical system in epileptic loss of consciousness. Epilepsia. 2001;42(Suppl 3):13–19. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2001.042suppl.3013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jay TM, Witter MP. Distribution of hippocampal CA1 and subicular efferents in the prefrontal cortex of the rat studied by means of anterograde transport of Phaseolus vulgaris-leucoaglutinnin. J Comp Neuro. 1991;313:574–586. doi: 10.1002/cne.903130404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarland NR, Haber SN. Thalamic relay nuclei of the basal ganglia form both reciprocal and nonreciprocal cortical connections, linking multiple frontal cortical areas. J Neurosci. 2002;22:8117–8132. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-18-08117.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna JT, Vertes RP. Afferent projections to nucleus reuniens of the thalamus. J Comp Neuro. 2004;480:115–142. doi: 10.1002/cne.20342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre DM, Gilby KL. Mapping seizure pathways in the temporal lobe. Epilepsia. 2008;49(Supl 3):23–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeren HKM, Pijn JPM, van Lujtelaar ELJPM, Coenen AML, Lopes de Silva FH. Cortical focus drives widewpread corticothalamic networks during spontaneous absence seizures in rats. J Neurosci. 2002;22:1480–1495. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-04-01480.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeren HKM, Veening JG, Moderscheim TAE, Coenen AML, van Luijtelaar G. Thalamic lesions in a genetic rat model of absence epilepsy: dissociation between spike-wave discharges and sleep spindles. Exp Neurol. 2002;217:25–37. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell As, Baxter MG, Gaffan D. Dissociable performance on scene learning and strategy implementation after lesions to mangocellular mediodorsal thalamic nucleus. J Neurosci. 2007;27:11888–11895. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1835-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales GJ, Ramcharan EJ, Sundararaman N, Morgera SD, Vertes RP. Analysis of the Actions of Nucleus Reuniens and the Entorhinal Cortex on EEG and Evoked Populations Behavior of the Hippocampus. Proc. Of 29th Annual Int. Conf IEEE EMBS; 2007. pp. 2480–2484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muldor AB, Arts MPM, Lopes de Silva FH. Short and long-term plasticity of the hippocampus to nucleus accumbens and prefrontal cortex pathways in the rat, in vivo. Euro J Neuro. 1997;9:1603–1611. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1997.tb01518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namura S, Takada M, Kikuchi H, Mizuno N. Topographical organization of subicular neurons projecting to subcortical regions. Brain Res Bull. 1994;35:221–231. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(94)90126-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. 4. Academic Press; San Diego, CA, USA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Powell DA, Churchwell J. Mediodorsal thalamic lesions impair trace eyeblink conditioning in the rabbit. Learn and Mem. 2002;9:10–17. doi: 10.1101/lm.45302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray JP, Russchen FT, Fuller TA, Price JL. Sources of presemuptive glutamatergic/apartic afferents to the mediodorsal nucleus of the thalamus in the rat. J Comp Neuro. 1992;32:435–456. doi: 10.1002/cne.903200403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichova I, Sherman SM. Somatosensory corticothalmic projections: distinguishing drivers from modulators. J Neurophysiol. 2004;92:2185–2197. doi: 10.1152/jn.00322.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan DM, Bertram EH. Changes in midline thalamic recruiting responses in the prefrontal cortex of the rat during the development of chronic limbic seizures. Epilepsia. 2009;50:556–565. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson LW. A direct projection from ammon’s horn to prefrontal cortex in the rat. Brain Res. 1981;217:150–154. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(81)90192-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theyel BB, Llano DA, Sherman SM. The corticothalamocortical circuit drives higher-order cortex in the mouse. Nature Neuro. 2010;13:84–88. doi: 10.1038/nn.2449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Werf YD, Jolles J, Witter MP, Uylings HBM. Contributiions of thalamic nuclei to declarative memory functioning. Cortex. 2003;39:1047–1062. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(08)70877-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Werf YD, Witter MP, Groenwegen HJ. The intralaminar and midline nuclei of the thalamus. anatomical functional evidence for participation in processes of arousal and awareness. Brain Res Rev. 2002;39:107–140. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(02)00181-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verzeano M, Lindsley DB, Magoun HW. Nature of recruiting response. J Neurophysiol. 1953;16:183–195. doi: 10.1152/jn.1953.16.2.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viskontas IV, McAndrews MP, Moscovitch M. Remote episodic memory deficits in patients with unilateral temporal lobe epilepsy and excisions. J Neurosci. 2000;20:5853–5857. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-15-05853.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voltzenlogel V, Despres O, Vignal J-P, Steinhoff BJ, Kehrli P, Manning L. Remote memory in temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2006;47:1329–1336. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang DX, Bertram EH. Midline thalamic region: widespread excitatory input to the entorhinal cortex and amygdala. J Neurosci 2002. 2002;22:3277–3284. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-08-03277.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]