Abstract

Heart rate is a major factor influencing diagnostic image quality in computed tomographic coronary artery angiography (MDCT-CA) with an ideal heart rate of 60–65 beats/minute in humans. Using standardized contrast bolus volume, two different clinically applicable anesthetic protocols were compared for effect on cardiovascular parameters and 64-MDCT-CA quality in ten healthy dogs. The protocol using midazolam/fentanyl (A) was hypothesized to result in adequate reduction of heart rate achieving adequate image quality for MDCT-CA studies and having low impact on blood pressure, where as the protocol utilizing dexmedetomidine (B) was expected to result in reduction of heart rate to the target heart range resulting in excellent image quality while possibly showing undesirable effect on the blood pressure values measured.

Heart rate was 80.6 ± 7.5bpm with protocol A and 79.2 ± 14.2bpm with protocol B during image acquisition (P=1). R-R intervals allowing for the best depiction of the individual coronary artery segments were found in the end diastolic period and varied between the 70–95% interval. Diagnostic quality was rated excellent, good and moderate in the majority of the segments evaluated, with higher scores given for more proximal segments and lower for more distal segments respectively. Blur was the most commonly observed artifact and most affected the distal segments. There was no significant difference for the optimal reconstruction interval, diagnostic quality and measured length individual segments or proximal diameter of the coronary arteries between both protocols (P=1). Both anesthetic protocols and the standardized bolus volume allow for diagnostic quality coronary 64-MDCT-CA exams.

Keywords: Heart, computed tomography, dexmedetomidine, midazolam, fentanyl

Introduction

Individual variations of the anatomy of the coronary arteries, such as aberrant coronary arteries, can significantly alter treatment decisions for related congenital abnormalities in dogs1–3. Multidetector computed tomography coronary artery angiography (MDCT-CA) has recently been introduced as a non-invasive method to depict the coronary arteries in normal dogs4. 64-MDCT-CA exam was able to show the left main coronary artery and its three main branches (paraconal interventricular, septal and circumflex branch) as well as the right coronary artery. The anesthetic protocol used in that canine study did not result in the desired target heart rate of 60–65 beats/minute, which has been shown to result in optimal image quality in humans undergoing coronary MDCT-CA5. Furthermore, the use of nitroprusside as a vasodilator showed no significant effect on the visualized length or diameter of the coronary arteries in the canine study4, but caused significant hypotension so that the clinical applicability of this protocol is questionable. The use of nitroprusside improves the diagnostic accuracy of MDCT-CA in human due to improved vessel visibility and therefore optimized detection of anatomic variations or obstructive disease6. Canine coronary artery angiography with a clinically applicable anesthetic protocol that allows for adequate reduction of heart rate and therefore adequate diagnostic image quality for depiction of the coronary arteries has not been established.

In veterinary medicine, pre-anesthetic medications including fentanyl, midazolam and dexmedetomidine are commonly administered for many reasons including patient sedation, facilitation of intravenous catheter placement, and as induction agent and for their inhalant sparing effects. Since bradycardia is associated with the use of opioids (i.e. fentanyl) and alpha-2 adrenergic agonists (i.e. dexmedetomidine), these drugs should reduce heart rate following their administration, an effect necessary for high-quality images during MDCT-CA exams. In addition, the sedative (and cardiovascular) effects of these agents are reversible with pharmacologic antagonists readily available to the practitioner, a technique commonly employed following short diagnostic procedures7–12.

Thus, the aim of this study was to test two different, clinically applicable, anesthetic protocols for their effect on lowering heart rate and achieving diagnostic imaging quality for depicting coronary artery anatomy, diameter and length. We hypothesized protocols using midazolam and fentanyl would decrease the canine heart rate to target values necessary to achieve adequate image quality for canine coronary artery angiographic studies using MDCT while having low impact on blood pressure. In contrast, dexmedetomidine would decrease heart rate to the target range (resulting in excellent image quality) while possibly producing undesirable effects on the blood pressure.

Material and methods

Animal preparation

The University of Wisconsin’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all procedures of this prospective trial. Ten beagle dogs (mean ± 1 SD age 12.4 ± 3.3 months, body weight 10.7 ± 1.2 kg) underwent 64-MDCT-CA (Discovery CT750 HD, General Electrics Medical Systems, Waukesha, WI, USA) on two different days using one of two anesthetic protocols for each occasion in a randomized fashion. Randomizing was performed by withdrawing one of 10 slips of paper from a jar. Five papers were labeled with number 1 (midazolam/fentanyl = 1) and five were labeled with number 2 (dexmedetomidine = 2). The first chosen number was used on study day 1 and the other on study day 2. One 20G intravenous catheter was placed in the right and left cephalic vein each in all dogs; the left was used for anesthesia purposes and the right for contrast administration, connected to a dual barrel power injector line. EKG leads were placed on the food pads and EKG signal was recorded through the imaging software and used for determination of heart rate during image acquisition and number of cardiac cycles needed for image acquisition. Pulse-oximetry was used to monitor heart rate, rhythm and hemoglobin saturation. Non-invasive systolic, diastolic and mean arterial pressure was monitored using a Cardell® Veterinary Monitor (Model 9401, CAS Medical Systems, Branford, CT, 06405). Baseline heart rate was manually recorded just prior to anesthetic induction by auscultating the thorax. Heart rate, blood pressure and end-tidal CO2 were recorded once every 5-minutes immediately following anesthetic induction and instrumentation and for the duration of the anesthetic episode. Additionally the CT software recorded the heart rate during the short period of angiographic image acquisition.

Anesthesia protocols

Anesthetic protocol A consisted of premedication with intravenous fentanyl (5µg/kg; Fentanyl citrate, West-Ward, Eatontown, NJ 07724, USA) and midazolam (0.2mg/kg; Midazolam, Hospira, Inc., Lake Forest, IL 60045, USA) bolus followed by continuous rate infusion (0.2mg/kg/hr midazolam and fentanyl 10µg/kg/hr. Anesthetic protocol B consisted of intravenous premedication with dexmedetomidine (1µg/kg; Dexdomitor, Pfizer Animal Health, New York, New York, 10017) and followed by continuous rate infusion (dexmedetomidine 1µg/kg/hr). For both protocols, dogs were induced using a propofol bolus to effect (2–6 mg/kg IV) and maintained with isoflurane (1–2% vaporizer setting) in 100% oxygen administered via orotracheal tube in addition to the respective continuous rate infusion. Intravenous crystalloid Lactated Ringer’s Solution Solution (5–10 ml/kg/hr; Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL 60064) was also administered though the left cephalic catheter. End-tidal carbon dioxide levels were maintained at 35–45mmHg using a mechanical ventilator (SAV 2550 Small Animal Ventilator, Smiths Medical, Dublin, OH, 43017, USA). Short-term apnea was induced for the exams using mechanical hyperventilation and stopping ventilator activity immediately before initiation of the scan.

Coronary CTA

The CT exam was initiated 15min after reaching a stable anesthetic plane with the dog positioned on the patient couch of the 64-MDCT unit in a custom made V-trough in dorsal recumbency. First, a non-contrast exam of the whole thorax was performed to aid localizer placement for the following semi-automated bolus tracking (SmartPrep®). CTA was performed following the intravenous administration of 15ml iodinated contrast medium (Omnipaque 300, NovaPlus GE Healthcare, Princeton, NJ, USA; 420mgI/kg) and 5ml physiologic saline flush injected at 2ml/s and 325PSI. Using semi-automated bolus tracking, the angiographic CT scan was triggered when the contrast bolus reached the right ventricular outflow tract, as a 5 second scan delay was inherent to the machine software before initiating the retrospectively gated scan. Helical scan parameters were as follows: 80kVp, 200mA, 0.35s gantry rotation time, 40mm detector collimation (0.625mm × 64 detectors), 1.25mm slice thickness and spiral pitch factor 0.24. Images were reconstructed at 0.625mm isotropic resolution using a standard convolution kernel and 16cm display field of view.

After the imaging procedure, the dogs were humanely euthanized according to institutional protocol requirements and underwent gross necropsy for evaluation of the hearts and macroscopic coronary artery anatomy.

Image analysis

The images were post-processed to generate multiple data sets in 5% intervals within the cardiac cycle (4–94% R-R interval) as described previously4. Image evaluation was performed by a board certified veterinary radiologist (RD) in a randomized fashion, blinded to the individual anesthetic protocol used for the scans. Images were reviewed using dedicated viewing software13, window width and level were adjusted individually and three-plane as well as curved multiplanar reconstructions were applied as needed to optimize depiction of the coronary arteries.

For each scan contrast medium arrival time and the intensity of contrast enhancement at the base of the ascending aorta was recorded.

The diagnostic quality of the retrospectively gated exams was evaluated; the left and right coronary artery branches were subdivided into segments analogous to branching in humans, similar to our previous study4, 14. The R-R reconstruction interval allowing for optimal visualization of each segment was recorded; using this interval the diagnostic quality was evaluated for depiction of each individual segment (3 = excellent, 2 = good, 1 = moderate, 0 = poor or not visible; Figure 1) as well as for the presence of artifacts (yes/no; if yes: blur or stair step/motion was classified). The different artifacts could be simultaneously present per segment. The maximally-seen length of the right (RCA) and left (LCA) coronary arteries as well as the main branches of the right coronary artery (right marginal (RM), right circumflex (RCX)) and left coronary artery (left interventricular paraconal (LIVP), left circumflex (LCX), left septal (LS) branch) was recorded using a semi-automated vessel tracking function; additionally the diameter of the RCA, LCA, LIVP, LCX and LS was measured 2mm distal to their origin.

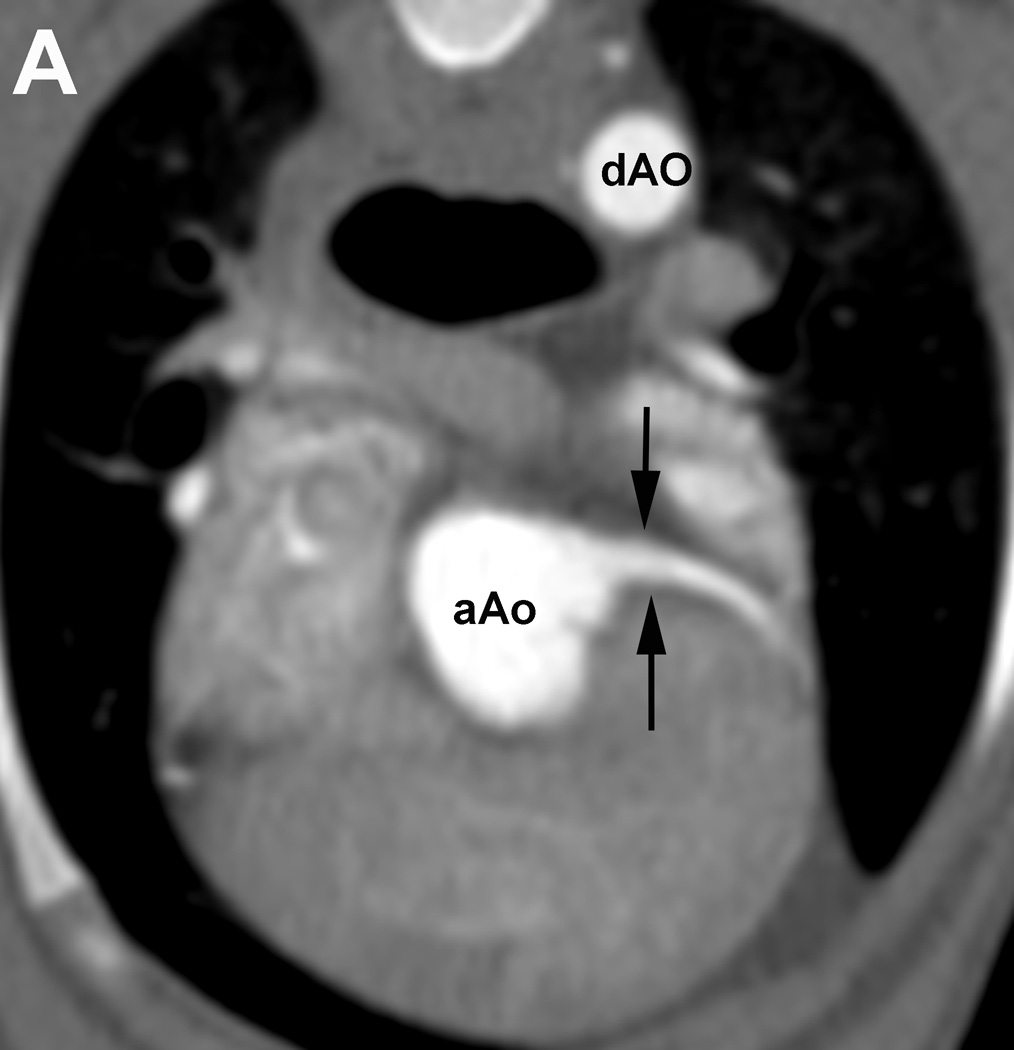

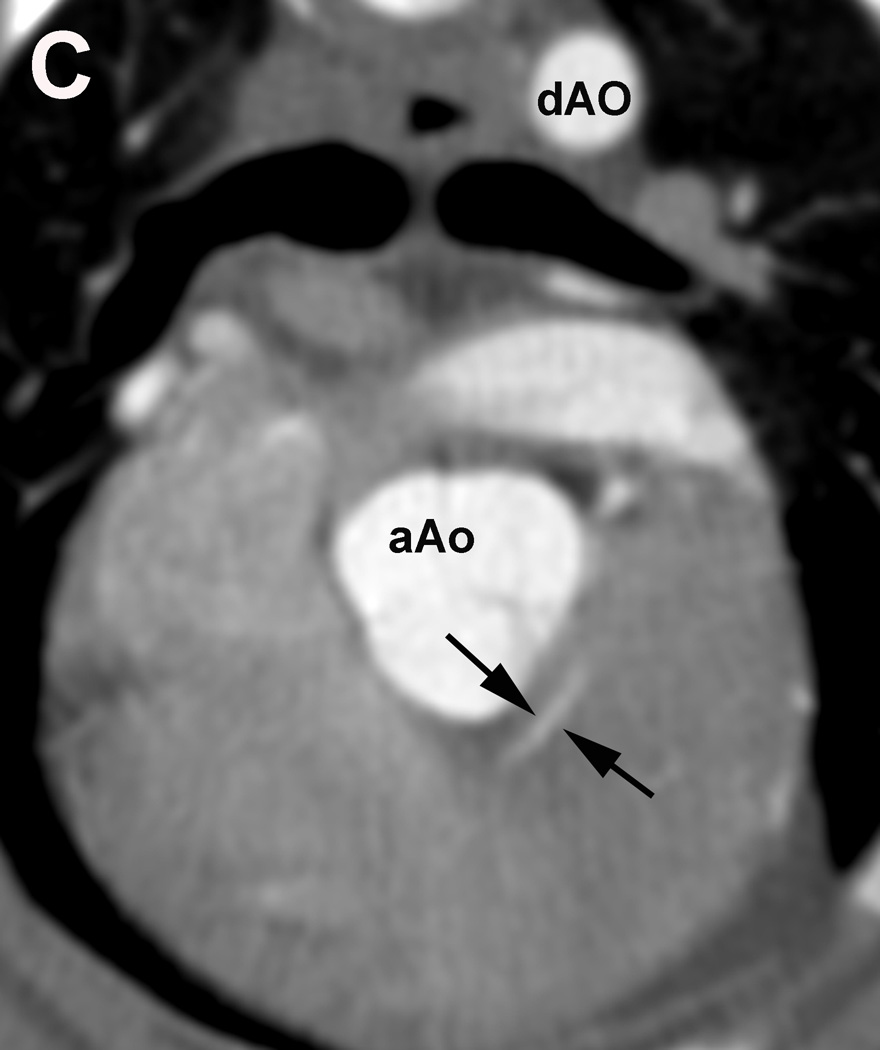

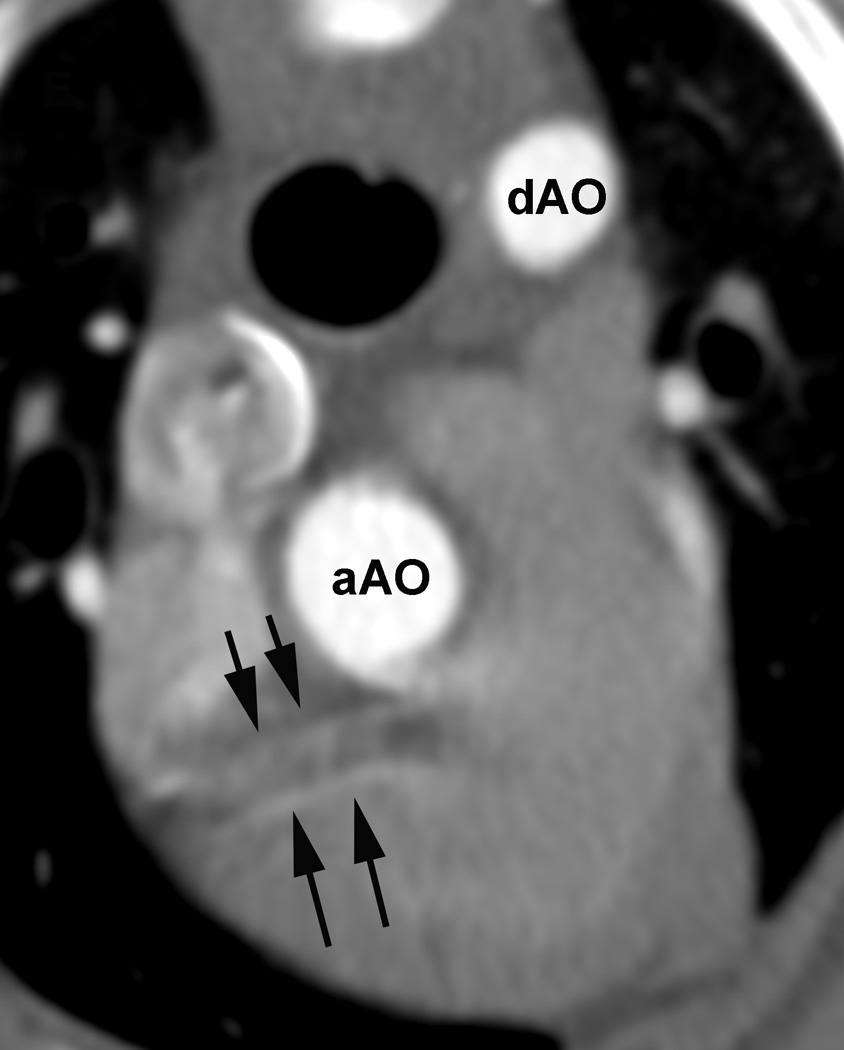

Figure 1.

Evaluation of the individual coronary artery segments: Excellent depiction of the left coronary artery (LCA) and the proximal portion of the left interventricular paraconal branch (LIVP 1, arrows; A). Good depiction of the right coronary artery (RCA 2, arrows; B). Moderate depiction of the right coronary artery, blur of the vessel margins is also present (RCA 2, arrows; C). Poor depiction of the distal segment of the left circumflex coronary artery, blur of the vessel margins is also present (LCX 4, arrows; D). Due to cardiac motion the right coronary artery (RCA 2) is depicted as two vessels (arrows, E). aAO = ascending aorta, dAO = descending aorta.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using R open source software15. Summary statistics were generated for all parameters evaluated. Continuous measures are summarized as mean ± 1 SD (standard deviation). For comparison of the vital parameters the Friedman rank sum test was used; then a pairwise comparison using the Wilcoxon signed rank test was performed and P-values were adjusted using the Holm-Bonferroni step down procedure16. Significance was set as P ≤ 0.05. A Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to compare the measured length and proximal diameter of the coronary artery segments for protocols A and B. Significance was set at P ≤ 0.05 and a Holm-Bonferroni step down procedure was performed16.

Results

No anesthetic complications were encountered in any of the dogs using either anesthetic protocol. The entire CT procedure including patient setup, acquisition of localizer images, pre-contrast thorax exam, the retrospectively gated cardiac exam until the patient was moved off the patient table lasted for 9.31 ± 0.17min; while the duration of the retrospectively gated coronary angiography itself was an average of 5.0s ± 0.68s and included an average of 6.4 ± 0.95 cardiac cycles.

The heart rate immediately prior to induction was 105 ± 16bpm for all studies. For the duration of the anesthetic procedure the mean heart rate was 81.1 ± 11.6bpm using protocol A and 84.1 ± 19.2bpm using protocol B, no significant difference was determined (P=1). During image acquisition for the CTA the mean heart rate was 80.6 ± 7.5 bpm using protocol A and 79.2 ± 14.2 bpm using protocol B, also no significant difference was present (P=1) and heart rate was considered stable during image acquisition in 16/20 dogs. One dog showed a rapid increase of heart rate immediately after the contrast medium injection in both anesthetic episodes. The heart rate of this dog returned to near-normal values within 10–15 minutes of contrast injection. Mean blood pressure was significantly higher (P > 0.05) using protocol B (Protocol A 62.9 ± 9.1 vs protocol B 72.4 ± 15.9mmHg).

Differences in scan delay (18.1 ± 3.4s Protocol A, 19.4 ± 5.0 Protocol B) and aorta enhancement (441.2 ± 231.6 HU Protocol A, 519.7 ± 203.1 Protocol B) with the two anesthesia protocols were not significant (P=1).

In this study, 14 coronary artery segments were investigated (LCA 0, LIVP 1–3, LS 1–2, LCX 1–4, RCA 1–2, RM, RCX). A total of 139 and 127 coronary artery segments using protocol A and B respectively were evaluated. One dog from protocol B had inadequate coronary artery enhancement for evaluation and was excluded from this analysis.

All optimal R-to-R reconstruction intervals were situated in the late diastolic phase, distributed between the 70–95% intervals. The optimal R-to-R reconstruction interval did not vary markedly within one dog between the two anesthetic episodes for the left or right coronary artery branches, respectively (P=1). An overview for the optimal reconstruction interval for the individual segments is given as a percentage of the R-to-R interval in Table 1.

Table 1.

Optimal R-R Reconstruction interval of the individual coronary artery segments in the cardiac cycle determined using protocol A (midazolam/fentanyl) and B (dexmedetomedine). In one dog the LIVP 3 segment was not seen using protocol A; a total of 139 segments were evaluated using protocol A. Using Protocol B one dog had poor intravascular contrast enhancement and only the LCA was seen; a total of 127 segments were evaluated using protocol B. There was no statistical difference for the optimal reconstruction interval for each segment between both protocols (P=1).

| Protocol A/B |

Reconstruction interval | # dogs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 70% | 75% | 80% | 85% | 90% | 95% | ||

| LCA | 1/1 | 3/2 | 1/2 | 2/1 | 2/1 | 1/2 | 10/9 |

| LVIP 1 | 1/2 | 3/1 | 1/3 | 2/1 | 2/1 | 1/1 | 10/9 |

| LVIP 2 | 1/2 | 3/1 | 1/3 | 2/1 | 2/1 | 1/1 | 10/9 |

| LVIP 3 | 1/2 | 2/1 | 1/3 | 2/1 | 2/1 | 1/1 | 9/9 |

| LS 1 | 1/2 | 3/1 | 1/4 | 2/− | 2/1 | 1/1 | 10/9 |

| LS 2 | 1/2 | 3/1 | 1/4 | 2/− | 2/1 | 1/1 | 10/9 |

| LCX 1 | 1/2 | 4/1 | 1/3 | 2/1 | 2/1 | −/1 | 10/9 |

| LCX 2 | 1/2 | 4/1 | 1/3 | 2/1 | 2/1 | −/1 | 10/9 |

| LCX 3 | 1/2 | 4/1 | 1/3 | 2/1 | 2/1 | −/1 | 10/9 |

| LCX 4 | 1/2 | 4/1 | 1/3 | 2/1 | 2/1 | −/1 | 10/9 |

| RCA 1 | 1/2 | 3/2 | 4/3 | 1/− | 1/2 | −/1 | 10/9 |

| RCA 2 | 1/2 | 3/2 | 3/3 | 1/− | 2/2 | −/− | 10/9 |

| RM | 1/2 | 3/2 | 3/3 | 1/− | 2/2 | −/1 | 10/9 |

| RCX | 1/2 | 3/2 | 4/3 | 1/− | 1/2 | −/− | 10/9 |

| # segments | 14/27 | 45/19 | 25/44 | 24/8 | 25/18 | 6/11 | |

| % segments | 10.07/21.26 | 32.37/14.96 | 17.99/34.65 | 17.27/6.3 | 17.99/14.17 | 4.32/8.66 | |

LCA, left main coronary artery; LIVP, left interventricular paraconalis branch of the left coronary artery; LS, left septal branch of the left coronary artery; LCX, circumflex branch of the left coronary artery; RCA, right coronary artery; RM, marginal branch of the right coronary artery; RCX, circumflex branch of the right coronary artery; #, number of.

The overall diagnostic quality was evaluated per segment and was rated as excellent in 23.5 and 24.4%, good in 27.1 and 28.4%, moderate in 32.1 and 40.9% and poor/not seen in 17.1 and 6.3% using protocol A and B, respectively (P=1). The lower scores were predominantly given for the more distal segments whereas the higher scores were predominantly given for the more proximal segments.

No artifact was observed in 22.9 and 24.4% of the evaluated segments using protocol A and B, respectively (P=1). In the segments where artifact was observed, blur dominated with 77.1 and 74.8% over 0.7 and 3.2% stairstep/motion observed with protocol A and B, respectively (P=1). Blur was most often encountered as a non-sharp depiction of the vessel margins and was mostly seen in the more distal segments, also influencing the overall diagnostic quality as described above.

There were no significant differences in visualized length or diameter between the two anesthetic protocols (P=1; except for maximal length of RCA length P=0.52 and maximal diameter of RCA P=0.84). The individual results for the semi-automated measurement of length of the coronary artery segments and the manual measurement of the diameter of the proximal portion of the segments are given in Table 3 and 4.

Table 3.

Averages of Maximally Visualized Length of the Left and Right Coronary Artery and Their Respective Branches Using Protocol A (Midazolam/Fentanyl) and B (Dexmedetomidine). No significant differences were determined between the protocols (P=1).

| Protocol A (mean ± SD) |

Protocol B (mean ± SD) |

P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LCA (cm) | 0.48 ± 0.7 | 0.55 ± 0.9 | 1 |

| LIVP (cm) | 4.89 ± 1.9 | 5.87 ± 1.3 | 1 |

| LS (cm) | 2.89 ± 1.2 | 2.98 ± 0.9 | 1 |

| LCX (cm) | 7.45 ± 2.3 | 8.28 ± 2.6 | 1 |

| RCA (cm) | 2.47 ± 0.3 | 2.62 ± 0.4 | 0.52 |

| RM (cm) | 2.98 ± 1.9 | 2.37 ± 0.7 | 1 |

| RCX (cm) | 2.87 ± 0.6 | 2.64 ± 0.8 | 1 |

LCA, left main coronary artery; LIVP, left interventricular paraconalis branch of the left coronary artery; LS, left septal branch of the left coronary artery; LCX: circumflex branch of the left coronary artery; RCA, right coronary artery; RM, marginal branch of the right coronary artery; RCX, circumflex branch of the right coronary artery.

Table 4.

Averages of maximally Visualized Diameter of the Left and Right Coronary Artery and Their Respective Branches Using Protocol A (Midazolam/Fentanyl) and B (Dexmedetomidine). No significant differences were determined between the protocols (P>0.05).

| Protocol A (mean ± SD) |

Protocol B (mean ± SD) |

P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LCA (cm) | 0.39 ± 0.4 | 0.39 ± 0.1 | 1 |

| LIVP (cm) | 0.22 ± 0.1 | 0.21 ± 0.1 | 1 |

| LS (cm) | 0.13 ± 0.0 | 0.13 ± 0.0 | 1 |

| LCX (cm) | 0.22 ± 0.0 | 0.22 ± 0.0 | 1 |

| RCA (cm) | 0.17 ± 0.04 | 0.49 ± 0.6 | 0.84 |

LCA, left main coronary artery; LIVP, left interventricular paraconalis branch of the left coronary artery; LS, left septal branch of the left coronary artery; LCX: circumflex branch of the left coronary artery; RCA, right coronary artery.

The left coronary artery anatomy was observed and evaluated as previously described4, however in this cohort the circumflex branch of the right coronary artery (RCX) was consistently seen and therefore also evaluated separate from the right marginal branch. This branch originates at the bifurcation of the RCA2 segment on the right lateral aspect of the heart. The right marginal branch (RM) runs caudoventrally along the lateral wall of the right ventricle towards the apex of the heart and the right circumflex branch continues in right caudodorsal direction in the coronary grove laterally along the right atrioseptal junction (RCX).

The gross anatomic evaluation of the hearts showed no abnormalities and the anatomy of the coronary arteries seen in the individual dogs corresponded to the description based on the CTA exams.

Discussion

Both anesthetic protocols allowed for excellent delineation of the left and right coronary arteries and their respective branches in the dog and there was no difference found for measured length and proximal diameter measured using either protocol.

The protocols used were directed at stabilizing the physiological heart rate of dogs (awake, normal rate is ~80–120bpm) as optimal diagnostic quality for coronary CTA studies is achieved in humans at a heart rate of 60–65bpm17, 18. A previous study in isoflurane-anesthetized dogs used esmolol and nitroprusside to attempt heart rate regulation and dilation of the coronary arteries and allowed for excellent depiction of the vessels, although with marked systemic hypotension; heart rate was also not consistently lowered4. Hypotension, if prolonged and/or severe, can threaten organ perfusion, causing injury and a state of “shock”. When organs such as the heart, brain, kidneys, liver and lungs are affected by hypotension, significantly patient morbidity and even mortality may result. Both anesthetic protocols applied in the current study consistently lowered the heart rate to a mean of approximately 80bpm. Even though this heart rate was higher than the desired heart rate of 60–65bpm, the generated image quality was overall very good and the coronary arteries and their branches were easily evaluated. It may be speculated that for evaluating the anatomy the canine heart rate may not be needed as low as in humans, where evaluation of small plaques is the prime focus of these exams. Additionally, differences in heart rate may be encountered based on age or possibly body weight of the patient19. Therefore, it may be hypothesized that heart rate control may play a lesser role for image quality in MDCT-CA in large breed dogs or dogs over one year of age; however, further studies to evaluate these protocols in a more varied population of dogs would be needed to validate this. Newer technologies such as dual source CT units allow further reduction in the acquisition time. Also, recently developed advanced applications such as and adaptive prospective triggering may further reduce the need of heart rate control20.

For both anesthetic protocols an injectable drug was used for premedication and as continuous rate infusion during maintenance, reducing the minimal alveolar concentration (MAC) of inhalant needed. For Protocol A, a combination of midazolam and fentanyl was used. Midazolam acts as a GABAA receptor agonist7 and at clinical doses, midazolam has little effect on the cardiopulmonary system but exhibits cardiovascular depression used at very high doses8, 21. Only clinically relevant doses of midazolam were used to here for anesthetic-sparing effects and to facilitate multimodal anesthesia. Fentanyl acts as an µ-opioid receptor agonist and is commonly used in dogs for analgesia9, 10. Administration is routinely performed as a bolus followed by a constant rate infusion due to its rapid onset of action and short duration22. In awake animals, fentanyl produces minimal cardiac depression11, whereas it is associated with bradycardia in isoflurane-anesthetized dogs23. Together, these agents were efficacious in reducing the inhalant level required, minimizing direct cardiovascular depression, and achieving acceptable target heart rate for MDCT-CA in this study.

For Protocol B, dexmedetomidine, a α-2 adrenergic receptor agonist, was used. Administration results in sedation and analgesia; constant rate infusions are also associated with bradycardia and profound cardiovascular depression, even at low doses12, 24–27. Thus, although it reduced the canine heart rate in our study to an acceptable level, its use may not be recommended in dogs with cardiovascular disease.

These investigations did not result in the same degree of hypotension as reported in our previous study using esmolol4. This is most likely due to the absence of beta-adrenergic receptor blockade from esmolol and vascular smooth muscle relaxation and vasodilation from nitroprusside administration. Especially protocol A, which combines midazolam and fentanyl, may be clinically applicable.

In the previous feasibility study4, the contrast bolus volume was considerably larger than the current, weight-based bolus volume recommendation of 2ml/kg in companion animals28, 29. Here, we aimed to minimize the bolus volume to minimize fluid overloading while still preserving optimal visualization of the small cardiac vessels. A standard bolus volume of 15ml contrast medium and 5ml saline chaser was used; this equaled approximately 2ml/kg bolus volume in the study population and would be applicable in clinical patients. The saline chaser is used to advance contrast medium that would otherwise be wasted in the tubing or trailing in venous the circulation from the injection site and mainly serves to produce an optimized tight bolus profile30, 31 The scan delay applied here was longer than reported previously4. This study was performed on a different MDCT unit compared to the previous study; the current unit had a longer delay than expected from triggering the diagnostic scans to starting the diagnostic scan. This was addressed by triggering the scan with contrast arrival in the right heart to account for the circulation time of the contrast medium through the lung but could otherwise have been addressed with changing to a test bolus injection technique instead; the latter was not pursued to aim for consistency in experimental design. As a result, a larger standard deviation of the enhancement at the base of the aorta resulted, but diagnostic scan quality was achieved in all dogs except one dog using protocol B. This specific dog did show a rapid increase of heart rate to the contrast medium injection in both anesthetic episodes that might have contributed to faster advancement of the bolus through the heart and lungs, leaving insufficient contrast for defining the coronary artery branches. The heart rate of this dog returned to near-normal values within 10–15 minutes of contrast injection. The intravenous injection of non-ionic contrast media is generally well tolerated by dogs. In a study evaluating the effect of non-ionic contrast media injection in dogs undergoing cross-sectional imaging exams there was no change in heart rate, but a 2% incidence of hypertension32. Hypertension per se was not observed following contrast administration in our study but a slightly higher mean blood pressure was recorded when using protocol B.

The anatomic depiction of the left and right coronary artery branches was easily performed when evaluating the coronary CTA exams and agreed with the gross anatomical description of the proximal left and right coronary branches as inspected on gross necropsy. The gross anatomical description was focused on the proximal portion of the left and right coronary artery branches to detect anatomical variations and did not follow the small distal branches. We consider the depiction and correlation of the proximal portion of the coronary artery anatomy the main interest in canine patients at this time since aberrant coronary arteries may be of clinical significance. Even though coronary artherosclerosis has been reported in dogs3, the current understanding of the canine cardiac anatomy and physiology attributes lower importance to obstructive coronary disease compared to people, as anastomoses are formed commonly in canines1–3.

The systematic reporting of coronary segments was done in accordance with that proposed by the American Heart Association in 1975 and adapted in a previous publication describing the coronary CTA anatomy in dogs4, 14. In this study population, the description of the distal segments of the right coronary artery was amended from the previous description4, as the right coronary artery split into a similarly developed circumflex and marginal branch all study subjects. This branch was not well observed in the previous study population and therefore not included in the evaluation at the time. As the dogs for the current and previous studies originated from a purpose breeding institution, one could speculate if the different breeding lines between the current and previous study contributed this discrepancy.

The R-R intervals for optimal depiction of the left and right coronary artery and their respective branches were found in the late diastolic phase, as expected from the previous canine study, yet differed from humans, where the 60–65% interval is recommended for heart rates around 65bpm using 64-MDCT4, 33, 34. There was little within-subject variation during a study and in the left or right coronary artery and their branches, but there was moderate inter-subject variation. Reconstructions were performed in 5% intervals and the distribution of the results throughout the 70–95% interval confirms the need for segmenting the data in 5% and not larger increments to optimize the visualization.

In this and the previous study, blur was the most commonly observed artifact4. The indistinct vessel margins relate to the limits of spatial resolution for these small structures. Motion or stair step artifact was found in only a few study subjects. Motion artifact commonly relates to the heart rate during the scan. Neither anesthetic protocol produced the optimal 60–65bpm heart rate35 and therefore motion artifact was expected. Neither of the artifacts affected the detection of the respective vessel.

There were no differences in the length of the canine coronary arteries between anesthetic protocols. The LCA and the LIVP were shorter compared to the previous reported length using coronary CTA, whereas the LS and LCX were comparable4. Additionally, the RCA was measured differently in the present study as the distal RM and RCX were measured separately; adding the RM to the RCA measurement would give comparable or slightly longer measurements as previously reported4. Anatomical measurements published describe 0.5cm for the left main coronary artery, 8cm for the left circumflex branch, 7cm for the left paraconal interventricular branch and 5cm for the RCA; a length has not been described in an anatomical study for the left septal branch36–38. As there was low inter-subject variation and our coronary CTA measurements are similar to the anatomical reports, we speculate that these are variations in the anatomy of these dogs originating from a different breeding line as the dogs used in the previous study4. Alternatively, the lower contrast bolus volume used in the current study may have affected measurements, however, we would expect a more systematic drift in the results and not an effect on two segments only.

The diameter of the coronary artery branches reported in this study is similar, yet somewhat smaller for multiple comparable measures reported in the previous study4. This might relate to the lower volume contrast bolus used or the difference in anesthetic protocols applied. As obstructive disease is not the primary focus for evaluation of the coronary arteries in dogs3 we accept this finding as a possible limitation that is outweighed by the clinically applicable anesthetic protocols and contrast bolus volume used which allow for very good depiction of the anatomy.

The main limitation of our study was the small sample size, which limits statistical power; consequently, caution should be applied in concluding that these protocols are equivalent when no significant differences are reported. Offsetting this is that each animal received both anesthetic protocols, which increase precision and limits intersubject variation. Still, ideally a larger cohort of dogs of different weights and breeds would be investigated, in addition to clinical patients. Also the variation in contrast enhancement achieved at the base of the aorta could possibly be remedied with applying the test bolus technique in future studies.

We conclude that both anesthetic protocols allowed similar and adequate reduction of the canine heart rate to achieve diagnostic quality canine coronary artery angiographic studies using 64-MDCT. Even though the target heart rate of <65bpm was not reached with either protocol, good image quality was achieved, allowing for depiction of the left and right coronary artery and their respective branches as well as measurement of their diameter and length. No significant difference was found for these parameters comparing both anesthetic protocols. Both protocols were well tolerated by the study subjects, but protocol B resulted in higher systemic blood pressures. Therefore, clinically used anesthetic protocols need to be chosen on an individual patient basis, taking into consideration patient signalment and disease processes as the tested protocols may not be suitable for all patients. Evaluating this technique in clinical patients with suspected aberrant coronary arteries or obstructive disease is desirable.

Table 2.

Overall Diagnostic Quality of the Coronary Artery Segment Depiction using Protocol A and B as well as Scoring for Artifacts is given. The LVIP 3 segment was not seen in one dog using Protocol A; one dog was excluded of the evaluation (except from LCA) of Protocol B as poor contrast enhancement was present. There was no statistical difference for the given parameters for each segment between both protocols (P=1).

| Protocol A/B |

Overall Diagnostic Quality of Segment | Artifact | # Dogs |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Excellent | Good | Moderate | Poor/not seen |

No | Yes | |||

| Blur | Stair step/Motion |

|||||||

| LCA | 8/8 | 2/− | −/1 | −/− | 8/9 | 2/1 | −/− | 10/9 |

| LVIP 1 | 7/8 | 3/1 | −/− | −/− | 7/8 | 3/1 | −/− | 10/9 |

| LVIP 2 | −/1 | 5/6 | 4/2 | 1/− | −/− | 10/8 | −/1 | 10/9 |

| LVIP 3 | −/− | 1/1 | 4/5 | 4/3 | −/− | 10/9 | −/1 | 10/9 |

| LS 1 | 1/1 | 4/5 | 5/3 | −/− | 1/1 | 9/8 | −/− | 10/9 |

| LS 2 | 3/− | 1/2 | 1/4 | 5/3 | 1/− | 9/9 | −/− | 10/9 |

| LCX 1 | 7/9 | 3/− | −/− | −/− | 7/1 | 3/− | −/− | 10/9 |

| LCX 2 | 4/1 | 3/6 | 3/2 | 2/− | 4/− | 6/9 | −/1 | 10/9 |

| LCX 3 | −/− | 3/3 | 4/6 | 5/− | −/− | 10/9 | −/− | 10/9 |

| LCX 4 | −/− | 1/− | 3/7 | −/2 | 1/− | 9/9 | −/− | 10/9 |

| RCA 1 | 3/2 | 7/7 | −/− | −/− | 3/1 | 7/5 | 1/1 | 10/9 |

| RCA 2 | −/− | 5/5 | 5/4 | −/− | −/− | 10/9 | 10/9 | |

| RM | −/− | −/− | 7/9 | 3/− | −/− | 10/9 | 10/9 | |

| RCX | −/− | −/− | 9/9 | 1/− | −/− | 10/9 | 10/9 | |

| # segments | 33/31 | 38/36 | 45/52 | 24/8 | 32/31 | 108/95 | 1/4 | |

LCA, left main coronary artery; LIVP, left interventricular paraconalis branch of the left coronary artery; LS, left septal branch of the left coronary artery; LCX: circumflex branch of the left coronary artery; RCA, right coronary artery; RM, marginal branch of the right coronary artery; RCX, circumflex branch of the right coronary artery; # dogs, number of dogs.

Acknowledgments

Funding sources:

The project was supported by the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program, previously through the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) grant 1UL1RR025011, and now by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), grant 9U54TR000021. Additionally the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program, through the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), supported Dr. Johnson grant UL1TR000427

References

- 1.Buchanan JW. Pulmonic stenosis caused by single coronary artery in dogs: four cases (1965–1984) Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 1990;196:115–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buchanan JW. Pathogenesis of single right coronary artery and pulmonic stenosis in English Bulldogs. J Vet Int Med. 2001;15:101–104. doi: 10.1892/0891-6640(2001)015<0101:posrca>2.3.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu S, Tappe JP, Fox PR. Clical and pathological findings in dogs with atheroclerosis: 21 cases. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1986:227–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drees R, Frydrychowicz A, Reeder SB, Pinkerton ME, Johnson R. 64-multidetector computed tomographic angiography of the canine coronary arteries. J Vet Radiol & Ultrasound. 2011;52:507–515. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8261.2011.01826.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Menke J, Unterberg-Buchwald C, Staab W, Sohns JM, Seif Amir Hosseini A, Schwarz A. Head-to-head comparison of prospectively triggered vs retrospectively gated coronary computed tomography angiography: Meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy, image quality, and radiation dose. Am Heart J. 2013;165:154–163. e153. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2012.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chun EJ, Lee W, Choi YH, Koo BK, Choi SI, Jae HJ, et al. Effects of nitroglycerin on the diagnostic accuracy of electrocardiogram-gated coronary computed tomography angiography. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2008;32:86–92. doi: 10.1097/rct.0b013e318059befa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seddighi R, Egger CM, Rohrbach BW, Cox SK, Doherty TJ. The effect of midazolam on the end-tidal concentration of isoflurane necessary to prevent movement in dogs. Vet Anaesth Analg. 2011;38:195–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2995.2011.00615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones DJ, Stehling LC, Zauder HL. Cardiovascular responses to diazepam and midazolam maleate in the dog. Anesthesiology. 1979;51:430–434. doi: 10.1097/00000542-197911000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steagall PV, Teixeira Neto FJ, Minto BW, Campagnol D, Correa MA. Evaluation of the isoflurane-sparing effects of lidocaine and fentanyl during surgery in dogs. J Am Vet Medical Assoc. 2006;229:522–527. doi: 10.2460/javma.229.4.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aguado D, Benito J, Gomez de Segura IA. Reduction of the minimum alveolar concentration of isoflurane in dogs using a constant rate of infusion of lidocaine-ketamine in combination with either morphine or fentanyl. Vet J. 2011;189:63–66. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2010.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grimm KA, Tranquilli WJ, Gross DR, Sisson DD, Bulmer BJ, Benson GJ, et al. Cardiopulmonary effects of fentanyl in conscious dogs and dogs sedated with a continuous rate infusion of medetomidine. Am J Vet Res. 2005;66:1222–1226. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.2005.66.1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uilenreef JJ, Murrell JC, McKusick BC, Hellebrekers LJ. Dexmedetomidine continuous rate infusion during isoflurane anaesthesia in canine surgical patients. Vet Anaesth Analg. 2008;35:1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2995.2007.00344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosset A, Spadola L, Ratib O. OsiriX: an open-source software for navigating in multidimensional DICOM images. J Digit Imaging. 2004;17:205–216. doi: 10.1007/s10278-004-1014-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Austen WG, Edwards JE, Frye RL, Gensini GG, Gott VL, Griffith LS, et al. A reporting system on patients evaluated for coronary artery disease. Report of the Ad Hoc Committee for Grading of Coronary Artery Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery, American Heart Association. Circulation. 1975;51:5–40. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.51.4.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holm S. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics. 1979;17:571–582. [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Graaf FR, Schuijf JD, van Velzen JE, Kroft LJ, de Roos A, Sieders A, et al. Evaluation of contraindications and efficacy of oral Beta blockade before computed tomographic coronary angiography. Am J Cardiol. 2010;105:767–772. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.10.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Graaf FR, Schuijf JD, Delgado V, van Velzen JE, Kroft LJ, de Roos A, et al. Clinical application of CT coronary angiography: state of the art. Heart Lung Circ. 2010;19:107–116. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferasin L, Ferasin H, Little CJ. Lack of correlation between canine heart rate and body size in veterinary clinical practice. J Small An Pract. 2010;51:412–418. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-5827.2010.00954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pan CJ, Qian N, Wang T, Tang XQ, Xue YJ. Adaptive prospective ECG-triggered sequence coronary angiography in dual-source CT without heart rate control: Image quality and diagnostic performance. Exp Ther Med. 2013;5:636–642. doi: 10.3892/etm.2012.828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heniff MS, Moore GP, Trout A, Cordell WH, Nelson DR. Comparison of routes of flumazenil administration to reverse midazolam-induced respiratory depression in a canine model. Acad Emerg Med. 1997;4:1115–1118. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1997.tb03692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sano T, Nishimura R, Kanazawa H, Igarashi E, Nagata Y, Mochizuki M, et al. Pharmacokinetics of fentanyl after single intravenous injection and constant rate infusion in dogs. Vet Anaesth Analg. 2006;33:266–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2995.2005.00266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keating SC, Kerr CL, Valverde A, Johnson RJ, McDonell WN. Cardiopulmonary effects of intravenous fentanyl infusion in dogs during isoflurane anesthesia and with concurrent acepromazine or dexmedetomidine administration during anesthetic recovery. Am J Vet Res. 2013;74:672–682. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.74.5.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pascoe PJ, Raekallio M, Kuusela E, McKusick B, Granholm M. Changes in the minimum alveolar concentration of isoflurane and some cardiopulmonary measurements during three continuous infusion rates of dexmedetomidine in dogs. Vet Anaesth Analg. 2006;33:97–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2995.2005.00236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Braz LG, Braz JR, Castiglia YM, Vianna PT, Vane LA, Modolo NS, et al. Dexmedetomidine alters the cardiovascular response during infra-renal aortic cross-clamping in sevoflurane-anesthetized dogs. J Invest Surg. 2008;21:360–368. doi: 10.1080/08941930802440803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin GY, Robben JH, Murrell JC, Aspegren J, McKusick BC, Hellebrekers LJ. Dexmedetomidine constant rate infusion for 24 hours during and after propofol or isoflurane anaesthesia in dogs. Vet Anaesth Analg. 2008;35:141–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2995.2007.00365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ebner LS, Lerche P, Bednarski RM, Hubbell JA. Effect of dexmedetomidine, morphine-lidocaine-ketamine, and dexmedetomidine-morphine-lidocaine-ketamine constant rate infusions on the minimum alveolar concentration of isoflurane and bispectral index in dogs. Am J Vet Res. 2013;74:963–970. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.74.7.963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sieslack AK, Dziallas P, Nolte I, Wefstaedt P. Comparative assessment of left ventricular function variables determined via cardiac computed tomography and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in dogs. Am J Vet Res. 2013;74:990–998. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.74.7.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pollard RPS. CT Contrast media and applications. In: SChwarz TSJ, editor. Veterinary Computed Tomography. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011. pp. 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Utsunomiya D, Awai K, Sakamoto T, Nishiharu T, Urata J, Taniguchi A, et al. Cardiac 16-MDCT for anatomic and functional analysis: assessment of a biphasic contrast injection protocol. AmJ Roent. 2006;187:638–644. doi: 10.2214/AJR.05.0612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kerl JM, Ravenel JG, Nguyen SA, Suranyi P, Thilo C, Costello P, et al. Right heart: split-bolus injection of diluted contrast medium for visualization at coronary CT angiography. Radiology. 2008;247:356–364. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2472070856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pollard RE, Puchalski SM, Pascoe PJ. Hemodynamic and serum biochemical alterations associated with intravenous administration of three types of contrast media in anesthetized dogs. Am J Vet Res. 2008;69:1268–1273. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.69.10.1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leschka S, Husmann L, Desbiolles LM, Gaemperli O, Schepis T, Koepfli P, et al. Optimal image reconstruction intervals for non-invasive coronary angiography with 64-slice CT. Eur Radiol. 2006;16:1964–1972. doi: 10.1007/s00330-006-0262-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rahmani N, Jeudy J, White CS. Triple rule-out and dedicated coronary artery CTA: comparison of coronary artery image quality. Acad Radiol. 2009;16:604–609. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2008.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kimura F, Umezawa T, Asano T, Chihara R, Nishi N, Nishimura S, et al. Coronary computed tomography angiography using prospective electrocardiography-gated axial scans with 64-detector computed tomography: evaluation of stair-step artifacts and padding time. Jpn J Radiol. 2010;28:437–445. doi: 10.1007/s11604-010-0448-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Evans H. The heart and the arteries. In: HE E, editor. Miller's anatomy of the dog. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1993. pp. 598–601. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koch T, Berg R. Blutgefäß- und Lymphsystem, Angiologia. In: Koch TBR, editor. Lehrbuch der Veterinär-Anatomie: Die grossen Versorgungs- und Steuerungssyteme. Stuttgart: Gustav Fischer Verlag Jena; 1993. pp. 45–62. [Google Scholar]

- 38.König H, Liebich HG. Organe des Herz-Kreislauf-Systems. In: König HLH, editor. Anatomie der Haussäugetiere. Stuttgart: Schattauer GmbH; 2005. pp. 445–448. [Google Scholar]