Abstract

Septic cardiomyopathy is a severe complication among some patients who develop group A streptococcal toxic shock syndrome (StrepTSS). Despite the importance of cardiac dysfunction in determining prognosis, very little is known about mechanisms that reduce cardiac output in association with streptococcal infection. Here, we investigated the effects of streptococcal extracellular toxins on mechanical contractility of electrically paced primary murine cardiomyocytes. Our data demonstrate that Streptolysin O (SLO) is the major streptococcal toxin responsible for cardiomyocyte contractile dysfunction. SLO dose-dependently affected cardiac myocyte function in discrete stages. Exposure to SLO caused a failure of cardiac cells to respond to electrical pacing, followed by spontaneous dysregulated contractions and augmented strength of contraction. Central to these SLO-mediated effects is a marked influx of calcium into the cytosol through SLO-mediated pores in the cytoplasmic membrane. Such calcium mobilization in response to SLO correlated temporally with hypercontractility and unpaced contractions. During continued exposure to SLO, cardiomyocytes exhibited periods of reversion to normal electrical pacing suggestive of membrane lesion repair and restoration of calcium handling. Together, these observations are consistent with the clinical observation that septic cardiomyopathy is a reversible condition in patients that survive StrepTSS. These data provide strong evidence that streptococcal exotoxins, specifically SLO, can directly impact cardiac mechanical function.

Keywords: Cardiomyopathy, Streptococcal Toxic Shock Syndrome, group A streptococcus, dilated cardiomyopathy, cholesterol-dependent cytolysins, septic shock, Streptococcus pyogenes

INTRODUCTION

The gram-positive human pathogen Streptococcus pyogenes (group A streptococcus; GAS) causes a variety of illnesses, ranging in severity from asymptomatic carriage to toxic shock syndrome. Life-threatening GAS infections remain a significant cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. In the United States, these infections occur with an annual frequency of ~3.5 cases per 100,000 and a mortality of 30–85% (1;2). Of these, approximately one-third of patients develop Streptococcal Toxic Shock Syndrome (StrepTSS) (2). Survivors require prolonged hospitalization and oftentimes undergo amputations or other aggressive surgical debridement.

In our original series of 20 patients with StrepTSS (2), one patient developed myocardial depression. Since then, Forni et al reported 6 patients with StrepTSS-associated cardiomyopathy (3) and one case was described by the Massachusetts General Hospital (4). More recently, we evaluated 20 patients with StrepTSS who developed decreased cardiac function as measured by either echocardiography, calculated cardiac index (CI) or both (5). All patients experienced dramatic reductions in cardiac index, global hypokinesia and severely reduced ejection fractions. Mortality was 55% overall and 70% in those with CI <2.5. Survivors suffered severe morbidities including symmetrical gangrene of digits and limbs, blindness and cognitive impairments, especially in patients who received aggressive vasopressor therapy. In three surviving patients, echocardiograms done >6 months after recovery demonstrated complete resolution of both the ejection fraction deficits and the hypokinetic left ventricular contractility (5). These clinical data demonstrate that severe, reversible cardiomyopathy develops in a subset of patients with StrepTSS.

Mechanisms underlying the suppression of cardiac function in response to GAS remain largely undefined. We have recently shown that: a) cardiomyocytes mount a unique, and potentially detrimental, immune response to direct GAS stimulation with expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and MIP-2 and b) macrophages produce soluble mediators that upregulate cardiomyocyte-derived IL-6, TNF-α and MIP-2 expression (6). These and other cardiomyocyte-derived immune factors which we term “cardiokines” may contribute to the early cardiac response to GAS bacteremia during the acute phase of infection.

Potent GAS virulence factors might also directly impact cardiac function. GAS produces several extracellular toxins, including the pore-forming toxin streptolysin O (SLO). SLO belongs to a family of the cholesterol-dependent cytolysins (CDCs) and forms extraordinarily large pores (250–300 Angstroms) in host cell membranes (reviewed in (7)). Produced as a soluble monomer, SLO transforms to a membrane-bound oligomeric pre-pore complex that aggregates and inserts into the cyotosolic membrane forming a transmembrane β-barrel pore (8;9). While the importance of SLO in the rapid destruction of infected tissue has been demonstrated (10), little is known regarding its role in cardiac dysfunction.

In the present study, we investigated whether SLO, or other GAS exotoxins, could directly suppress cardiomyocyte function in vitro. We demonstrate that exotoxins from wild-type, but not SLO-deficient, GAS abruptly and markedly disrupted contraction of primary cardiomyocytes. This aberrant mechanical response to electrical pacing, characterized by irregular contractions interspersed with exceedingly strong contractions, was reproduced using recombinant SLO alone at sub-cytotoxic levels. Such transient contractile dysfunction resulted from marked increases in intracellular calcium that occurred independently of membrane ion-sensitive calcium channel activity. Studies using pore-incompetent structural mutants of SLO showed that mature pore formation and membrane disruption were required for this activity. These data suggest that neutralization of circulating SLO may have therapeutic benefit in patients with StrepTSS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial Strains and Exotoxin Preparation

Three clinical isolates of S. pyogenes were used, including: 1) strain 02/021, an M-type 1 GAS isolated from the blood of a fatal case of StrepTSS with cardiomyopathy; 2) strain 96/004, an M-type 1 GAS associated with invasive infection, and 3) strain 00/069, an M-type 5 GAS associated with invasive infection. Bacteria were cultured in Todd Hewitt Broth (THB) at 37°C in 5% CO2 with shaking (125 rpm) to mid-log phase for exotoxin preparations. Bacteria were removed by centrifugation and culture supernatants were filter-sterilized (0.22 μm) and stored at −70°C. Exotoxin activity (SLO, SpeB, and NADase) for each strain was quantified from log phase culture supernatants by sheep erythrocyte lysis assay (11), azocasein hydrolysis assay (12), and NADase spectrophotometric assay (13), respectively (Table I). GAS strain 96/004 produced SpeB, SLO and NADase activity, whereas strain 02/021 lacked detectable SpeB activity and strain 00/069 lacked NADase activity. Strain 00/070, an isogenic SLO knockout of strain 00/069 was previously constructed by Fontaine, et al (14).

Table I.

| GAS1 | SLO (HU/mL)2 | SpeB (μg/ml)3 | NADase (U/ml)4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 96/004 | 2 | 12.8 ± 4.8 | 0.26 ± 0.05 |

| 02/021 | 12 | ND5 | 2.88 ± 0.22 |

| 00/069 | 2 | ND | ND |

| 00/070 | 0 | 3.8 ± 1.5 | ND |

Log phase culture supernatants were collected from the indicated group A streptococcus (GAS) strains to assay SLO, SpeB and NADase activity.

Specific activity of SLO was determined by hemolysis of sheep red blood cells (11).

SpeB activity was measured by azocasein hydrolysis assay (12).

NADase activity was determined by spectrophotometric assay (13).

ND, not detected.

Recombinant Protein Expression and Purification

Plasmid constructs for expression of 6x histidine-tagged oxygen-stable SLOC533A, monomer-locked SLOC533A/T393C/V418C, and prepore-locked SLOC533A/G130C/S264C were developed using methods previously described for other pore-forming toxins (8;15;16) with some modifications. BL21 Escherichia coli harboring individual SLO plasmids were grown in Terrific Broth containing ampicillin (75 μg/mL). At an OD600 of 0.5, gene expression was induced with 1 mM IPTG for 4 hours. Bacteria were harvested by centrifugation and pellets were resuspended in BugBuster® protein extraction reagent (EMD Millipore, Gibbstown, NJ) supplemented with lysozyme (1 kU/mL; Sigma), benzonase nuclease (25 U/mL; EMD Millipore), and a broad-spectrum protease inhibitor cocktail (cOmplete ULTRA, Roche). Lysates were cleared by centrifugation and the resulting supernatant was purified on a 5 mL HisTrap HP column (GE Healthcare) using an imidazole gradient (20 to 500 mM) in binding buffer (20 mM sodium phosphate, 0.5 M sodium chloride, 20 mM imidazole, pH 7.4). Buffer exchange into DPBS was performed on a Sephadex G-25 column and glycerol was added to 20%. Specific hemolytic activity of oxygen-stable rSLO was ~2800 HU/mg of protein. As expected, neither the monomer-locked rSLO nor prepore-locked rSLO had measurable hemolytic activity due to their inability to form mature pores.

Primary Cardiomyocyte Isolation

All studies involving animals were approved by the Boise VA Medical Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Ventricular cardiomyocytes were isolated from 8- to 12-week-old female C57BL/6 mice (Charles River Laboratories) using methods described by Liao and Jain (17). In brief, 200 U heparin was administered to deeply anesthetized mice (65 mg/kg pentobarbital) prior to heart removal. Excised hearts were placed in ice-cold perfusion buffer, pH 7.46 (Alliance for Cellular Signaling (AfCS) Solution PS00000451, UCSD Signaling Gateway). After cannulation of the aorta using a 22-gauge blunted needle, hearts were perfused with 9 mL perfusion buffer (37°C) at a constant flow rate of 3 mL/min. Hearts were then digested with 30 mL of perfusion buffer containing 7.2 mg collagenase D (Roche, Indianapolis, IN), 9.6 mg collagenase B (Roche), 1.2 mg protease type XIV (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and 12.5 μM CaCl2. Ventricles were subsequently minced in myocyte stopping buffer 2 (AfCS Solution PS00000450). Cardiac ventricular myocytes were disassociated using a sterile transfer pipette, the cell suspension passed through a 250 μm nylon mesh and myocytes were allowed to settle for 15 min. Calcium was gradually reintroduced by mixing myocyte stop buffer 2 with Tyrode’s buffer (137 mM NaCl, 5.4 mM KCl, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES, 5.5 mM glucose, pH 7.4, 37°C) at ratios of 29:1, 13:2, 2:1, and 1:2, respectively, allowing cells to settle in each solution for 15 min. The final cell pellet was transferred to Tyrode’s buffer containing 1.8 mM CaCl2 and cell concentration was adjusted to 2.5 × 104 cells per mL.

Measurement of Cardiomyocyte Contractile Function

Mechanical properties of cardiomyocytes were assessed using an IonOptix™ video-based edge-detection system (IonOptix LLC, Milton, MA). In brief, isolated cardiomyocytes were placed in a thermostated (35°C) chamber mounted on the stage of an inverted microscope (Olympus, IX-70) and perfused with Tyrode’s buffer. Only rod-shaped, clearly striated myocytes were selected for analysis. To begin, cells were electrically paced at 2 Hz (0.5 ms, 5 V) for 2 min in Tyrode’s buffer to establish a stable baseline. Filter-sterilized streptococcal exotoxins (1:20 to 1:400 dilution), recombinant SLO (rSLO; 0.14 HU/mL), or Tyrode’s buffer (negative control treatment) were perfused over paced cardiomyocytes at a constant flow rate (0.5 mL/min). Myocyte contractility was recorded using the IonOptix system and SarcLen Sarcomere Length Acquisition Module. This system permitted determination of the magnitude and velocity of sarcomere shortening, and the relaxation/re-lengthening time. Measurements for each treatment group were collected from a minimum of 5 sarcomeres from 2–7 independent cardiac myocyte isolations; pacing measurements were recorded for a minimum of 4 min under control paced (2 Hz) conditions. Cells treated with the L-type calcium channel blocker, verapamil (Sigma), were electrically paced and treated with culture supernatants for 2 min prior to addition of verapamil (10 μM). Both verapamil and culture supernatant treatments were continued for the duration of the pacing protocol.

Measurement of Intracellular Calcium Transients

Intracellular calcium (iCa2+) levels were measured simultaneously with contractile function on the IonOptix system. Isolated cardiomyocytes were loaded with the cell-permeable ratiometric calcium indicator dye, Fura-2/AM (1 μM; Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) for 5 min prior to analysis. Following a 10 min washout, cardiac myocytes were paced at 2 Hz for 2 min in Tyrode’s buffer followed by treatment with recombinant SLO as described above. iCa2+ transients were recorded using 340/380 nm excitation wavelengths for ratiometric measurement of Fura-2 fluorescence at 510 nm (Fluorescence System Interface, IonOptix). Results are expressed as the 340/380 nm excitation ratio, indicating free iCa2+ levels.

RESULTS

Streptococcal Culture Supernatants Severely Alter Cardiomyocyte Contractility

The effects of streptococcal exotoxins on cardiomyocyte ultrastructure and mechanical function were studied on cardiac cells isolated from the hearts of healthy C57BL/6 mice. Greater than 60% of isolated primary cardiomyocytes were viable rod-shaped cells with clear sarcomere striations. The remainder of isolated cardiac cells were either hyper-contracted, appearing shorter and with rounded ends, or were rounded dead/dying cells. This isolation efficiency is comparable to previously published reports of primary cardiomyocyte isolation (17). Viable, rod-shaped cardiomyocytes were treated with streptococcal culture supernatants (CSN) to observe direct toxin-induced changes to the cellular ultrastructure. No gross differences in cellular morphology or relative abundance of viable myocytes were observed in resting, non-paced cardiomyocytes following a 10 min treatment with up to 1:20 dilution of sterile-filtered streptococcal CSN (strains 00/069, 02/021, and 96/004; data not shown) demonstrating that these conditions are sub-cytopathic. Next, cardiomyocytes were electrically paced to assess the role of streptococcal exotoxins on cellular contractility. Initial pacing experiments (2 Hz) established that isolated cardiomyocytes maintained a rod-shaped morphology with uniform and reproducible contractions throughout a ≥ 8 min pacing protocol in Tyrode’s buffer (Fig 1A, 1B). In contrast, treatment of paced cardiomyocytes with streptococcal CSN (strain 00/069) resulted in severe contractile dysfunction. Within 4 min, CSN-treated cardiomyocytes exhibited marked sarcomere shortening, reduced response to electrical stimulation, and spontaneous (non-paced) contractions that varied greatly in magnitude (Fig 1C, 1D). This aberrant response progressed to cellular fibrillation (at 5 to 8 min) and cells became tetanic and assumed a hyper-contracted morphology.

Figure 1. A streptococcal exotoxin severely disrupts mechanical contraction of murine cardiomyocytes.

Electrically paced primary murine cardiomyocytes were treated with A, B) Tyrode’s buffer alone or C, D) filter-sterilized log-phase culture supernatants from S. pyogenes strain 00/069 (1:20; 0.1 HU/mL). Sarcomere lengths from individual cardiomyocytes were recorded for 4 min during perfusion with the indicated treatments using the IonOptix™ video-based edge-detection system (Materials and Methods). Panels A and C represent an expanded view of cardiomyocyte contractility over 4 min. Shaded intervals (~14 s) in A and C are enlarged in B and D, respectively, to highlight cellular responsiveness to electrical pacing (2 Hz) and contraction amplitude (shortening of sarcomere length). Data shown are representative of 5 independent experiments using primary cells from different animals.

Streptolysin O Rapidly Alters Cardiomyocyte Contractility

The response of cardiomyocytes to sterile streptococcal supernatants indicated that a potent extracellular toxin(s) mediated the observed contractile dysfunction. Thus, culture supernatants from several GAS clinical isolates (strains 00/069, 02/021, and 96/004), all of which express SLO pore-forming toxin (Table I) were tested. Each supernatant induced similar dysfunction in cardiomyocytes irrespective of the amount or type of other exotoxins produced. These data suggested that an extracellular toxin common to all GAS isolates was responsible. One such candidate was streptolysin O (SLO). Indeed, the pronounced cardiomyocyte arrhythmia did not develop in cells treated with CSN from an isogenic SLO-deficient GAS (strain 00/070) (Fig 2A, 2B). Furthermore, treatment of isolated cardiomyoctes with a recombinant oxygen-stable form of SLO (rSLO; 0.14 HU/mL) reproduced the aberrant contractions observed in response to sterile streptococcal supernatants (Fig 2C, 2D) while cells treated with other recombinant streptococcal exotoxins (i.e., NADase or SpeB) exhibited normally paced contractions, similar to control treatment (data not shown). Together, these data demonstrate that SLO solely mediates the profound cardiomyocyte contractile dysfunction.

Figure 2. Streptolysin O disrupts mechanical contraction of murine cardiomyocytes.

Electrically paced primary murine cardiomyocytes were treated with A, B) filter-sterilized log-phase culture supernatants from the SLO-deficient S. pyogenes strain 00/070 (1:20) or C, D) recombinant SLO (0.14 HU/ml; 48 ng/ml) in Tyrode’s buffer. Sarcomere lengths from individual cardiomyocytes were recorded for 4 min during perfusion with the indicated treatments, as above (Fig. 1). Panels A and C represent an expanded view of cardiomyocyte contractility over 4 min. Shaded intervals (~14 s) in A and C are enlarged in B and D, respectively, to highlight cellular responsiveness to electrical pacing (2 Hz) and contraction amplitude (shortening of sarcomere length). Data shown are representative of 7 independent experiments using primary cells from different animals.

SLO Mediates Contractile Dysfunction through Altered Calcium Mobility

Contraction of cardiac myocytes is controlled principally by intracellular calcium (iCa2+) transients. To determine whether SLO perturbs calcium levels within cardiac cells, contractility and intracellular calcium were simultaneously measured in primary cardiomyocytes loaded with the fluorescent calcium indicator dye, Fura-2. Throughout an electrical pacing protocol, contraction frequency and amplitude directly corresponded with peak levels of iCa2+ (Fig 3). Exposure to recombinant SLO affected both cardiomyocyte contractility and induced Ca2+ transients in defined stages. During stage I, normal contraction frequency and Ca2+ transients were observed in response to electrical pacing, although a reduced magnitude of cellular contractions in Fura-2 loaded cells was evident (Fig 3A) in comparison to non-labeled cells (Fig 1). Stage II was characterized by an increased iCa2+ level that failed to return to baseline (Fig 3B), a lack of myocyte contraction in response to electrical pacing and a slight decline in overall sarcomere length. Stage III followed with an abrupt onset of stronger contractions, persistent failure to respond to electrical pacing and markedly increased iCa2+. Together, a sustained increase in iCa2+ observed after treatment with SLO (stages II–III) suggested that the inability of cardiomyocytes to appropriately regulate SLO-induced changes in iCa2+ contributed to the disruption of paced contractions. In stages IV–V, myocyte contractions demonstrated a trend toward normal electrical pacing although the amplitude of contractions remained markedly elevated, potentially due to iCa2+ buffering by Fura-2. By stage V, iCa2+ homeostasis was largely restored (Fig 3B), as evidenced by a return of iCa2+ levels to baseline following contraction in SLO-treated cells.

Figure 3. Streptolysin O-induced arrhythmia is mediated by changes in intracellular calcium.

Fura-2-loaded cardiomyocytes were perfused with recombinant SLO (0.034 HU/ml). A) Sarcomere length and B) intracellular calcium (Fura-2 340/380nm fluorescence excitation ratio) were simultaneously measured from individual electrically paced cardiomyocytes (Materials and Methods). Stages (I–V) highlight different phases of the cardiomyocyte response to rSLO in the presence of Fura-2. Data shown are representative of 3 independent experiments using primary cells from different animals.

SLO-mediated Cardiomyocyte Dysfunction is Independent of Voltage-gated Calcium Channels

To determine whether SLO-mediated cardiomyocyte dysfunction was dependent upon activation of L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, isolated cardiomyocytes were treated with the calcium channel blocker, verapamil (Fig 4). Cardiomyocytes perfused with log-phase CSN from GAS strain 02/021 (diluted 1:200 in Tyrode’s buffer) showed normal paced contractions during initial exotoxin exposure followed by the expected arrhythmic and spontaneous contractions described above. Addition of 10 μM verapamil substantially reduced the strength of cardiomyocyte paced contractions following treatment with Tyrode’s buffer (Fig 4A). Similarly, addition of verapamil after 2 min of exposure to exotoxins from GAS strain 02/021(Fig 4B–E) reduced the initial strength of contractions. However, despite continued perfusion of verapamil, strong and asynchronous contractions were observed in GAS exotoxin-treated cardiomyocytes (Fig 4B, E), comparable to those seen in response to other streptococcal supernatants (Fig 1C) or recombinant SLO (Fig 2C) without calcium channel blockade. Failure of verapamil to attenuate the aberrant response to streptococcal exotoxins supports the notion that SLO-induced contractile dysfunction occurs independently of voltage-gated L-type Ca2+ channel activity.

Figure 4. Streptolysin O-induced contractile dysfunction is independent of L-type voltage gated calcium channels.

Cardiomyocytes were isolated as described (Materials and Methods). Individual, electrically paced cardiomyocytes were continuously perfused with A) Tyrode’s buffer or B–E) filter-sterilized log-phase culture supernatants from S. pyogenes strain 02/021 (1:200; 0.06 HU/mL). At 2 min, 10 μM verapamil was added to the perfusate in both treatment groups. Sarcomere length from cardiomyocytes was recorded using the IonOptix™ video-based edge-detection system, as described. Representative charts in A and B show > 6 min of cardiomyocyte contractions following treatment. Three shaded intervals (~14 s each) in B are enlarged in C–E to highlight cellular responsiveness to electrical pacing (2 Hz) and contraction amplitude (shortening of sarcomere length) during treatment: C) cardiomyocyte contraction prior to addition of verapamil, D) reduced amplitude of contractions following addition of verapamil, E) dysregulated, amplified contractions resulting from S. pyogenes supernatant despite the continued presence of verapamil. Data shown are representative of 4 independent experiments using primary cells from different animals.

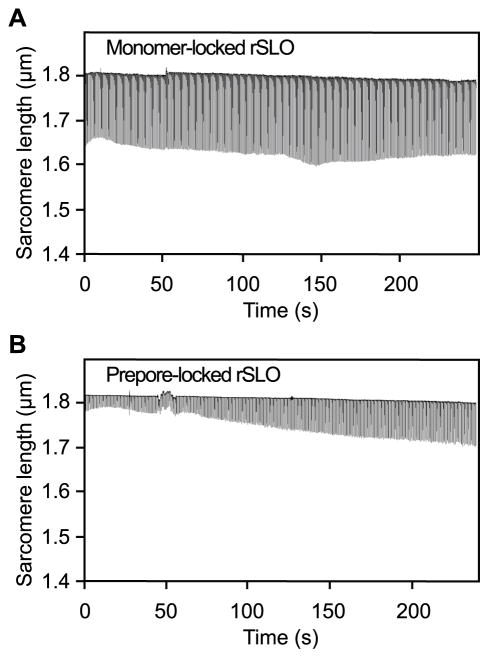

Mature Pore Formation Leads to SLO-mediated Cardiomyocyte Dysfunction

Streptolysin O pore formation provides a plausible mechanism for altered calcium mobility in cardiomyocytes, contributing to aberrant cellular contractions. To determine whether mature pore formation is required for SLO-mediated cardiomyocyte dysfunction, cellular contractions were analyzed in response to recombinant SLO constructs that were “locked” as either a membrane-bound monomer or as a prepore complex that fails to insert into the cellular membrane (8;15;16). Neither monomeric (Fig 5A) nor prepore-locked (Fig 5B) rSLO was capable of disrupting myocyte contractility, even at 10 times the concentration of pore-competent SLO used to elicit contractile dysfunction described above. These findings establish that neither membrane binding nor multimeric assembly of SLO on the cellular surface is sufficient for disruption of myocyte contractility, suggesting that mature pore formation is required for SLO-mediated cardiomyocyte dysfunction.

Figure 5. Streptolysin O pore formation in the cytoplasmic membrane is required for myocyte contractile dysfunction.

Isolated cardiomyocytes were perfused with A) recombinant monomer-locked Streptolysin O (480 ng/ml) or B) Recombinant prepore-locked Streptolysin O (480 ng/ml) in Tyrode’s buffer. Sarcomere lengths from individual cardiomyocytes were recorded over 4 min following perfusion with the indicated treatments using the IonOptix™ video-based edge-detection system (Materials and Methods). Plots highlight cellular responsiveness to electrical pacing (2 Hz) and contraction amplitude (shortening of sarcomere length) following each treatment. Data shown are representative of 2 independent experiments using primary cells from different animals.

DISCUSSION

The mortality of StrepTSS remains between 30–60% despite modern medical interventions. The sudden onset of tachycardia, hypotension and organ failure often precedes a specific diagnosis of group A streptococcus as the etiologic agent. Since > 80% of deaths due to StrepTSS (2) and GAS bacteremia (18) occur during this early stage, cardiovascular dysfunction is suspect in contributing to the high mortality and rapid, fulminant course of this infection. In fact we recently demonstrated reduced cardiac outputs and or global hypokinesia in a subset of 20 patients with StrepTSS (5), a finding corroborated by others (3). Among StrepTSS patients, both survivors and non-survivors show low cardiac output during the initial 48–96 h (5). In follow-up studies of survivors, cardiac function returned to normal after weeks to months (5).

Interestingly, histopathology of cardiac tissue from autopsies of StrepTSS patients has revealed little evidence of tissue necrosis, coronary vessel thrombosis or inflammation (3;5), suggesting that intrinsic cardiac myocyte dysfunction contributes to hemodynamic collapse. This could be the consequence of a dysregulated host immune response or could result from the direct effects of GAS exotoxins on cardiac function, or both. While cytokines such as TNFα have been clearly implicated as mediators of septic shock in general (reviewed in (19)), and in StrepTSS specifically (20), the direct roles of the various GAS extracellular virulence factors on acute and sustained cardiac dysfunction have not been fully elucidated.

Data reported here convincingly demonstrate that the pore-forming GAS cholesterol-dependent cytolysin, SLO, is the sole bacterial exotoxin responsible for direct, acute StrepTSS-associated ventricular contractile dysfunction. Streptolysin O was first described as a bacterial cardiotoxin by Bernheimer and Cantoni in the mid-1940’s (21). Electrocardiograms from rabbits given small, sublethal doses of highly purified SLO showed a rapid onset of reversible ventricular arrhythmia and ventricular fibrillation (22). As was detected in our study, Goullet et al demonstrated a transient, positive inotropic effect of SLO on isolated rat ventricular strips (23). Subsequent studies into the mechanisms responsible alternately suggested that SLO caused: a) elevated plasma potassium concentrations following intravascular red cell hemolysis, b) release of vasoactive substances, or c) direct effects on the conduction apparatus. Using sophisticated genetic constructs of SLO lacking either the ability to oligomerize or to insert into the membrane, we herein demonstrate that mature pore formation and the subsequent massive calcium influx are responsible for the acute cardiotoxic effects of SLO to ventricular myocytes. The processes of monomer oligomerization and insertion are time- and concentration-dependent and thus account for the dose-dependent lag time between SLO administration and the onset of the response seen in the present study. Further, this mechanism also accounts for the relatively rapid onset of contractile dysfunction once a critical number of pores have formed.

Thus, in the early stages of infection, small amounts of circulating SLO would be sufficient to initiate cardiac dysfunction. Later, as more SLO is elaborated into circulation, increased numbers of mature pores on heart cell membranes would allow maximal influx of calcium into the cell. This influx would overwhelm the normal calcium handling mechanisms, resulting in ventricular cardiomyocyte dysfunction that is manifested clinically as global hypokinesia in these patients. In contrast, Takeda et al demonstrated that infusion of sub-lethal amounts of SLO, or a related toxin listeriolysin (LLO) in rats resulted in inhibition of atrio-ventricular conduction and bradycardia (24). These latter findings are not typical of patients with StrepTSS who have marked sinsus tachycardia (3;5).

As infection progresses, other strain-specific GAS virulence factors, such as the streptococcal superantigens, could further exacerbate StrepTSS cardiomyopathy. Superantigens elicit large-scale mononuclear cell production of the cytokines TNF-α and IL-1β and the lymphokines IL-2 and TNF-β (reviewed in (25)) – all of which are well known cardiac depressant factors (reviewed in (19)). Streptococcal superantigens could also directly suppress myocardial contractility as we have demonstrated for S. aureus superantigen TSST-1 (26). However, data from the current study argues against this notion since no functional abnormalities were induced by supernatant from the SLO-deficient strain which also produced SpeA and SpeB.

Local production of inflammatory mediators by the myocardium itself has also been implicated in myocyte dysfunction (reviewed in (27)). Indeed, we have shown that a) cardiomyocytes mount a unique, and potentially detrimental, immune response to direct GAS stimulation with expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and MIP-2, and that b) macrophages produce soluble mediators that upregulate cardiomyocyte-derived IL-6, TNF-α and MIP-2 expression (6), Further, our laboratory has demonstrated that unstimulated cardiomyocytes actively maintain macrophage functional quiescence (28) and that GAS challenge over-rides this quiescence mechanism and boosts macrophages production of MMP-9 and expression of cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6) and cardiodepressant factors (iNOS) (28). These cardiomyocyte-derived effectors of macrophage function (which we called “cardiokines”) illustrate the integral role of cardiomyocytes themselves in the host response to GAS infection. Paracrine communication among these cell types and the resultant local increase in cytokines and proteinases could exacerbate the cardiac dysfunction in StrepTSS, resulting in profound hypotension, systemic perfusion deficits and subsequent organ failure.

The mechanism of SLO-induced cardiac dysfunction elucidated here contrasts markedly with that responsible for other types of sepsis-associated cardiac failure. For example, in a model of Gram negative sepsis induced by cecal ligation and puncture, L-type calcium channel activation contributed to the observed cardiac myocyte dysfunction (29). In staphylococcal toxic shock syndrome, alpha-hemolysin has been implicated as a mediator of cardiac dysfunction. However alpha-hemolysin’s well-known ability to form pores was not directly implicated in this process. Instead several presumably non-pore dependent mechanisms, including induction of apoptosis/necrosis (30) and thromboxane-mediated vasoconstriction (31;32), have been purported to mediate this pathology. The ability of alpha-hemolysin to activate the zinc metalloproteinase known as ADAM-10 and the subsequent dissolution of focal adhesion complexes (33), could also contribute.

Both SLO-mediated disruption of calcium transients and contractility deficits were reversible in the present study. These findings agree with early experimental studies in animals which showed that small, sublethal doses of SLO induced a transient sinus bradycardia followed by recovery (22) and are substantiated in humans with StrepTSS-associated cardiomyopathy in which normal cardiac function is restored in survivors (5). Indeed, repair of SLO-mediated pores has been demonstrated in non-cardiac cell lines where membrane sealing occurs through calcium and ATP-dependent endocytosis (34). Together these findings suggest that neutralization of SLO activity in vivo with specific neutralizing antibody may be of immediate benefit in patients with StrepTSS and evidence of cardiac dysfunction. Such a strategy may also prove efficacious in septic shock associated with other cholesterol-dependent cytolysin-producing organisms, such as Streptococcus pneumoniae.

Acknowledgments

Source of support: Funding for the current work was provided by the VA Merit Review Program (to DLS), U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research and Development, Biomedical Laboratory Research Program and a grant from the National Institutes of Health, NIAID 5R01AI037657 (to RKT).

This material is based upon work supported by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research and Development, Biomedical Laboratory Research Program.

Abbreviations

- GAS

group A streptococcus

- StrepTSS

streptococcal toxic shock syndrome

- SLO

Streptolysin O

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.O’Loughlin RE, Roberson A, Cieslak PR, et al. The epidemiology of invasive group A streptococcal infection and potential vaccine implications: United States, 2000–2004. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(7):853–862. doi: 10.1086/521264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stevens DL, Tanner MH, Winship J, et al. Severe group A streptococcal infections associated with a toxic shock-like syndrome and scarlet fever toxin A. N Engl J Med. 1989;321(1):1–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198907063210101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forni AL, Kaplan EL, Schlievert PM, Roberts RB. Clinical and microbiological characteristics of severe group A streptococcus infections and streptococcal toxic shock syndrome. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21(2):333–340. doi: 10.1093/clinids/21.2.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoadley DJ, Mark EJ. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Weekly Clinicopathological exercises. Case 28-2002. A 35-year-old long-term traveler with a rapidly progressive soft-tissue infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(11):831–837. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcpc020112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stevens DL, Shelly M, Stiller R, Villasenor-Sierra A, Bryant AE. Acute reversible cardiomyopathy in patients with streptococcal toxic shock syndrome. Proceedings & Abstracts of the XVIIth Lancefield International Symposium on Streptococci and Streptococcal Diseases; Porto Heli, Greece. 2008. Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li Z, Bryant AE, Hamilton SM, Bayer CR, Ma Y, Stevens DL. Do cardiomyocytes mount an immune response to Group A Streptococcus? Cytokine. 2011;54(3):258–265. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tweten RK. Pore-forming toxins in gram-positive bacteria. In: Roth JA, Bolin CA, Brogden KA, Minion C, Wannemuehler MJ, editors. Virulence Mechanisms of Bacterial Pathogens. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1995. pp. 207–229. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hotze EM, Wilson-Kubalek EM, Rossjohn J, Parker MW, Johnson AE, Tweten RK. Arresting pore formation of a cholesterol-dependent cytolysin by disulfide trapping synchronizes the insertion of the transmembrane beta-sheet from a prepore intermediate. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(11):8261–8268. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009865200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tweten RK, Parker MW, Johnson AE. The cholesterol-dependent cytolysins. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2001:25715–33. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-56508-3_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bryant AE, Bayer CR, Chen RY, Guth PH, Wallace RJ, Stevens DL. Vascular dysfunction and ischemic destruction of tissue in Streptococcus pyogenes infection: the role of streptolysin O-induced platelet/neutrophil complexes. J Infect Dis. 2005;192(6):1014–1022. doi: 10.1086/432729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bryant AE, Kehoe MA, Stevens DL. Streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxin A and streptolysin O enhance PMNL binding to protein matrixes. J Infect Dis. 1992:166165–169. doi: 10.1093/infdis/166.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eriksson A, Norgren M. The superantigenic activity of streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxin B is independent of the protease activity. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1999:25355–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1999.tb01360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stevens DL, Salmi DB, McIndoo ER, Bryant AE. Molecular epidemiology of nga and NAD glycohydrolase/ADP-ribosyltransferase activity among Streptococcus pyogenes causing streptococcal toxic shock syndrome. J Infect Dis. 2000;182(4):1117–1128. doi: 10.1086/315850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fontaine MC, Lee JJ, Kehoe MA. Combined contributions of streptolysin O and streptolysin S to virulence of serotype M5 Streptococcus pyogenes strain Manfredo. Infect Immun. 2003;71(7):3857–3865. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.7.3857-3865.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vadia S, Arnett E, Haghighat AC, Wilson-Kubalek EM, Tweten RK, Seveau S. The pore-forming toxin listeriolysin O mediates a novel entry pathway of L. monocytogenes into human hepatocytes. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7(11):e1002356. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramachandran R, Tweten RK, Johnson AE. Membrane-dependent conformational changes initiate cholesterol-dependent cytolysin oligomerization and intersubunit beta-strand alignment. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11(8):697–705. doi: 10.1038/nsmb793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liao R, Jain M. Isolation, culture, and functional analysis of adult mouse cardiomyocytes. Methods Mol Med. 2007:139251–262. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-571-8_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bucher A, Martin PR, Hoiby EA, et al. Spectrum of disease in bacteraemic patients during a Streptococcus pyogenes serotype M-1 epidemic in Norway in 1988. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1992;11(5):416–426. doi: 10.1007/BF01961856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dinarello CA. Proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines as mediators in the pathogenesis of septic shock. Chest. 1997;112(6 Suppl):321S–329S. doi: 10.1378/chest.112.6_supplement.321s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stevens DL, Bryant AE, Hackett SP, et al. Group A streptococcal bacteremia: The role of tumor necrosis factor in shock and organ failure. J Infect Dis. 1996;173(3):619–626. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.3.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bernheimer AW, Cantoni GL. The carditoxic action of preparations containing the oxygen-labile hemolysin of Streptococcus pyogenes : I. Increased sensitivity of the isolated frog’s heart to repeated application of the toxin. J Exp Med. 1945;81(3):295–306. doi: 10.1084/jem.81.3.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Halbert SP, Bircher R, Dahle E. The analysis of streptococcal infections. V. Cardiotoxicity of streptolysin O for rabbits in vivo. J Exp Med. 1961:113759–784. doi: 10.1084/jem.113.4.759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goullet P, Coraboeuf E, Breton D. Action of a purified Streptolysin O preparation on ventricular myocardial tissue. C R Hebd Seances Acad Sci. 1963:2571735–1738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takeda Y, Takeda T, Honda T, Miwatani T. Comparison of bacterial cardiotoxins: thermostable direct hemolysin from Vibrio parahaemolyticus, streptolysin O and hemolysin from Listeria monocytogenes. Biken J. 1978;21(1):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stevens DL, Kaplan EL. Streptococcal Infections: Clinical Aspects, Microbiology, and Molecular Pathogenesis. 1. New York: Oxford Univesity Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olson RD, Stevens DL, Melish ME. Direct effects of purified staphylococcal toxic shock toxin 1 on myocardial function of isolated rabbit atria. Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11(Suppl 1):S313–S315. doi: 10.1093/clinids/11.supplement_1.s313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mann DL. Stress activated cytokines and the heart. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 1996;7(4):341–354. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(96)00043-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Z, Bryant AE, Parimon T, Stevens DL. Cardiac dysfunction in StrepTSS: Group A streptococcus disrupts the directional cardiomyocyte-to-macrophage crosstalk that maintains macrophage quiescence. Cytokine. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2012.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Celes MR, Malvestio LM, Suadicani SO, et al. Disruption of calcium homeostasis in cardiomyocytes underlies cardiac structural and functional changes in severe sepsis. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e68809. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buerke U, Carter JM, Schlitt A, et al. Apoptosis contributes to septic cardiomyopathy and is improved by simvastatin therapy. Shock. 2008;29(4):497–503. doi: 10.1097/shk.0b013e318142c434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sibelius U, Grandel U, Buerke M, et al. Staphylococcal alpha-toxin provokes coronary vasoconstriction and loss in myocardial contractility in perfused rat hearts: role of thromboxane generation. Circulation. 2000;101(1):78–85. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grandel U, Bennemann U, Buerke M, et al. Staphylococcus aureus alpha-toxin and Escherichia coli hemolysin impair cardiac regional perfusion and contractile function by activating myocardial eicosanoid metabolism in isolated rat hearts. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(6):2025–2032. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819fff00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilke GA, Bubeck WJ. Role of a disintegrin and metalloprotease 10 in Staphylococcus aureus alpha-hemolysin-mediated cellular injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(30):13473–13478. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001815107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Idone V, Tam C, Goss JW, Toomre D, Pypaert M, Andrews NW. Repair of injured plasma membrane by rapid Ca2+-dependent endocytosis. J Cell Biol. 2008;180(5):905–914. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200708010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]