Abstract

Anxiolytic effects of perceived control have been observed across species. In humans, neuroimaging studies have suggested that perceived control and cognitive reappraisal reduce negative affect through similar mechanisms. An important limitation of extant neuroimaging studies of perceived control in terms of directly testing this hypothesis, however, is the use of within subjects-designs, which confound participants' affective response to controllable and uncontrollable stress. To compare neural and affective responses when participants were exposed to either uncontrollable or controllable stress, two groups of participants received an identical series of stressors (thermal pain stimuli). One group (“controllable”) was led to believe they had behavioral control over the pain stimuli while another (“uncontrollable”) believed they had no control. Controllable pain was associated with decreased state anxiety, decreased activation in amygdala and increased activation in nucleus accumbens (NAcc). In participants who perceived control over the pain, reduced state anxiety was associated with increased functional connectivity between each of these regions and ventral lateral/ventral medial prefrontal cortex (PFC). The location of PFC findings is consistent with regions found to be critical for the anxiolytic effects of perceived control in rodents. Furthermore, interactions observed between PFC and both amygdala and NAcc are remarkably similar to neural mechanisms of emotion regulation through reappraisal in humans. These results suggest that perceived control reduces negative affect through a general mechanism involved in the cognitive regulation of emotion.

Introduction

Perceived control has been defined as “the belief that one has at one's disposal a response that can influence the aversiveness of an event” (Thompson, 1981). A broad scientific literature has demonstrated the link between perceived control and mental and physical health. Animals exposed to uncontrollable stress experience deficits in learning and motivation as well as increased stress responses compared to animals exposed to similar amounts of controllable stress (Maier & Seligman, 1976; Weiss, Stout, Aaron, Quan, & et al, 1994). In humans, perception of control over life stressors is associated with reduced levels of depression and disease (Mineka, 1985). Maier and Watkins (Maier & Watkins, 1998) have argued that behavioral and neurochemical responses to uncontrollable stress are particularly relevant for understanding anxiety.

The neural mechanisms by which perceived control reduces negative emotional responses have been well delineated at the brainstem level in rodents (Maier & Watkins, 2005). Recent evidence suggests that while brainstem regions are critical, their involvement is dependent on the prefrontal cortex (PFC) and, in particular, the ventromedial PFC (vmPFC)(Amat et al., 2005). Functional neuroimaging has led to advances in our understanding of the role of the PFC in perceived behavioral control (Salomons, 2004; Wiech et al., 2006; Salomons, Johnstone, Backonja, Shackman, & Davidson, 2007). Of particular note, the ventrolateral (vlPFC) and vmPFC appear to be critically involved in modulating pain responses based on the perception of control (Wiech et al., 2006; Salomons et al., 2007). While these studies have provided a preliminary understanding of how perceived control alters the neural response to pain, they were not optimized for contrasting how a sustained level of perceived control alters neural and affective responses to repeated exposure to pain. These studies employed within-participants designs where participants received an equal amount of controllable and uncontrollable painful stress, such that the affective responses to controllable and uncontrollable stress were intermixed. Thus, participants' affective state reflected mixed success at controlling the painful stressor. In contrast, previous studies in which participants were exposed to either only controllable or only uncontrollable stressors, allowed for examination of how a sustained sense of control might alter the affective state. These studies evoked a range of behavioral responses in both humans and animals including deficits in learning and motivation and, of particular interest to the study at hand, affective responses resembling anxiety (Maier & Watkins, 1998; Maier & Seligman, 1976; Weiss et al., 1994). While the neural mechanisms of these effects have been examined in rodents, they have not been investigated in humans using in vivo neuroimaging techniques. The goal of the present study was to examine the neural mechanisms through which sustained levels of perceived control over a stressor (in this case pain) alters the affective response. Accordingly, we exposed two groups of healthy participants to a matched set of painful stressors and provided differential visual feedback such that one group believed they had behavioral control over the pain stimulus while the other group had the perception of a sustained lack of control over the pain stimulus.

Based on conceptual and anatomical overlap, it has been suggested (Wiech et al., 2006) that perceived control may alter the response to stressors through a mechanism similar to reappraisal (where the meaning of a stressful event is reinterpreted in order to alter the emotional response (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984; Lazarus, 1999). Neuroimaging studies of reappraisal and other forms of voluntary regulation of negative affect have primarily focused on the interplay between top down cortical processing and bottom up responses in subcortical regions such as the amygdala (Kim et al., 2011; Ochsner & Gross, 2005). The amygdala is differentially activated when individuals have perceived control over stress (Salomons, 2004). The amygdala has also been implicated in the generation of negative affective responses (Bishop, 2007; Shin & Liberzon, 2010), making it a region of interest for examining how perceived control alters anxiety. The interaction between amygdala and vmPFC has been implicated in the regulation of negative emotion (Kim et al., 2011). Additionally, extensive evidence points to a role for the vlPFC in regulating activation in the amygdala when reappraisal is used to down-regulate negative affect (Ochsner, Bunge, Gross, & Gabrieli, 2002; Schaefer et al., 2002; Ochsner et al., 2004; T. Johnstone, van Reekum, Urry, Kalin, & Davidson, 2007; Goldin, McRae, Ramel, & Gross, 2008; Kalisch, 2009). A recent reappraisal study (Wager, Davidson, Hughes, Lindquist, & Ochsner, 2008) found that downregulation of negative affect was associated with interactions not only between vlPFC and amygdala but also between vlPFC and the nucleus accumbens (NAcc) suggesting an additional subcortical region of interest. The potential involvement of the NAcc is not only consistent with its role in reappraisal, but a proposed role of the striatum in processing the affectively beneficial effects of choice and perceived control (Leotti, Iyengar, & Ochsner, 2010). This proposed role is based on the demonstrated role of NAcc in reward (Haber & Knutson, 2010) as well as findings that perceived control is inherently rewarding (Leotti & Delgado, 2011).

Based on the link between uncontrollable stress, anxiety, and the neural mechanisms of perceived control and reappraisal, the primary goals of the present study were 1) to examine how perceived control alters state anxiety in response to sustained exposure to painful stimuli and 2) to understand the interaction between subcortical regions involved in generating affect (amygdala, NAcc) and cortical regions involved in reappraisal and detection of control (vlPFC, vmPFC). We predicted that increased functional connectivity between these cortical and subcortical regions would be associated with anxiety reduction by perceived control.

An additional objective of the present study was to further investigate the effect of perceived control on the neural and perceptual response to pain. Previous neuroimaging studies (Salomons et al., 2007; Salomons, 2004; Wiech et al., 2006) have converged on common regions involved in this response (e.g. vlPFC, ACC), but have diverged in the conditions which elicit these responses. Similarly controversial are the effects of perceived control on pain perception, with some studies finding clear effects of perceived control on pain perception and others demonstrating null findings (Arntz & Schmidt, 1989; Thompson, 1981). Thus, while the primary focus of this report is the examination of the neural mechanisms underlying modulation of affective responses by perceived control, we also sought to clarify these controversies.

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited using campus advertisements. Individuals were excluded if they were left-handed, pregnant, claustrophobic, on analgesics (e.g., opioids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories), or had a current psychiatric or chronic pain disorder or a history of such disorders. They were screened for medical conditions that could affect pain sensitivity or regular use of drugs such as opioids or NSAIDS that could alter pain perception. As the experimental manipulation involved deception and was dependent on participants believing the instructions, psychology majors were excluded on the grounds that they might have familiarity with previous manipulations (e.g. learned helplessness experiments) in which participants were deceived about the amount of control they were able to exert. Participants signed informed consent and were randomized to the controllable and uncontrollable groups. Three participants were excluded because the post experimental questionnaire indicated that they had determined the intent of the experiment. Seven participants were excluded from the controllable group because they failed to reliably identify the response pattern to elicit positive visual feedback (see Experimental Session section). This yielded a final sample of 52 participants with 23 in the controllable group (12 female; M[SD]= 20.8 [2.6] years) and 29 in the uncontrollable group (14 female; M[SD]= 20.2 [2.1]). The Health Sciences Institutional Review Board of the University of Wisconsin-Madison approved the protocol.

Familiarization Session

A separate familiarization session was used to determine the level of thermal stimulation to be used in the subsequent fMRI imaging session. Thermal stimulation was delivered using a stimulator (TSA-II; http://www.medoc-web.com) connected to a 30×30 mm, MRI-compatible Peltier device affixed to the dorsal surface of the left forearm. Stimulation began at 32°C and increased by 0.7°C/second. Participants were instructed to terminate stimulation when their pain reached an 8 on an 11-point numeric rating scale (NRS) anchored by 0 (no-pain) and 10 (worst pain imaginable). This was repeated 10 times, with 30-second breaks between presentations. The mean temperature from the final 5 trials defined the painfully hot stimulus. This strategy for determining a level of thermal stimulation mirrors the one used in previous studies of perceived control (Salomons et al., 2004). The maximum temperature used in the experiment was not allowed to exceed 49°C. After titrating the thermal stimulation, participants were familiarized with the MR environment using a mock scanner, and were given one 10-second (“long”), five 5-second (“medium”) and four 2-second (“short”) heat stimuli to ensure that the experimental stimuli were painful but tolerable.

Thermal stimuli delivered during the experimental session (see below) were delivered to the dorsal surface of the left forearm with a ramp speed of 10°C/second for all participants.

Experimental Session

On the day of the experimental session, participants were given a four button keypad and were instructed that they would receive a series of short (2s), medium (5s), and long (10s) pain stimuli in a random, pre-set order. Each trial began with a 6-second visual cue 12 (±3) seconds prior to the onset of pain (see Figure 1a). Following offset of the pain stimulus, there was a 20-second gap, resulting in a total inter-stimulus interval of 32 (±3) seconds). During the inter-trial interval, subjects rated pain intensity and unpleasantness on a 0 – 10 numeric rating scale (NRS; for intensity: 0 = “No Pain”, 10 = “Most Intense Pain Imaginable”; for unpleasantness: 0 = “Not Unpleasant”, 10 = “Extremely Unpleasant”).

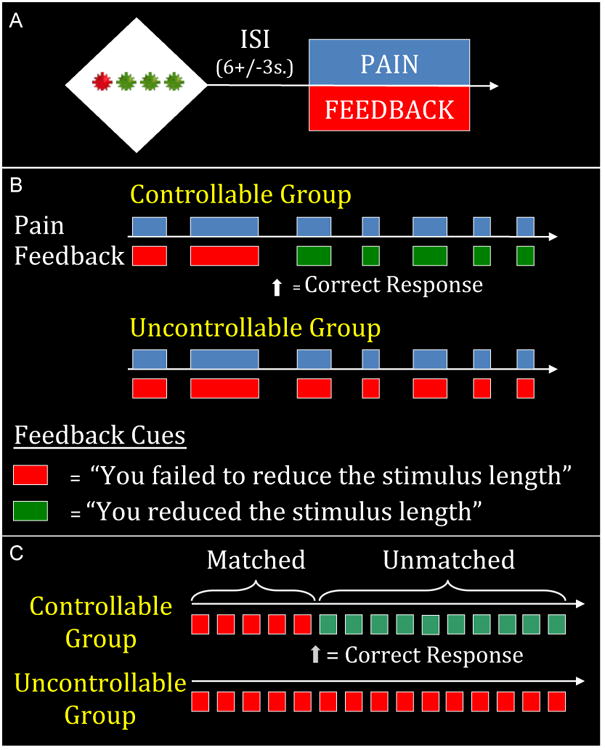

Figure 1. Study Design.

A) One single trial. Participants were given a button box and told that they could shorten the painful stimulation if they found the correct pattern of presses on the buttons corresponding to the green stars.

B) 2, 5 and 10 second stimuli were presented in the same proportion and order in both groups. The groups differed only in the visual feedback received. Participants in the uncontrollable group received consistent feedback indicating they had failed to exert control over the length of the heat (indicated in red). After figuring out the pattern, participants in the controllable group received feedback indicating that they had successfully controlled the length of the heat (indicated in green).

C) The analytic focus was the medium (5s) stimuli. On the first five (“matched”) trials, participants received identical painful stimuli and identical feedback. On the subsequent twenty (“unmatched”) trials participants received identical painful stimuli but differed in feedback and therefore perception of control.

The cue consisted of four stars (3 green, 1 red) and participants were told that they could shorten the length of the subsequent painful stimuli by finding the correct sequence of button presses on the keys corresponding to the green stars. They were told that if they pressed the correct sequence on a trial in which they were supposed to receive a ten second pain stimulus they would receive a five second stimulus and if they were supposed to receive a five second stimulus and made the correct response they would receive a two-second stimulus. They were told that 2-second stimuli could not be shortened. Participants were instructed that once the correct sequence had been discovered (as indicated by visual feedback), they would be able to shorten the heat on every subsequent trial by repeating that sequence. In order to ensure that all participants in the controllable group received identical feedback (and thus a similar affective experience), participants who did not identify the correct pattern or who did not persist with the correct pattern following initial success feedback were excluded (n=7).

To prevent the responses from becoming stereotyped and to maintain a level of interest, the red star appeared in a different position on each trial. The sequence of button presses, however, remained the same so that once participants identified the correct response sequence they could use it on all subsequent trials. For example, in Figure 1a, if the correct sequence was “Left, Middle, Right”, they would press buttons 2, 3 and 4. If the red star moved to position 2 on a subsequent trial they would press buttons 1, 3 and 4 to maintain the “Left, Middle, Right” pattern.

All participants irrespective of their perceived control group status received an identical sequence of fifty thermal stimuli (1 long, 25 medium, 24 short). Controllability was manipulated as follows: Following their discovery of the correct button sequence, the Controllable (C) group received visual feedback concurrent with the presentation of the thermal stimuli indicating that they had successfully reduced the duration of the thermal stimuli when they pressed the correct response sequence (or, in the case of 2-second trials which could not be shortened, feedback simply indicated that they had made the correct response). By contrast, the Uncontrollable (UC) group always received feedback indicating that they had failed to make the correct response sequence and thus failed to control the duration of the heat (see Figure 1b). Thus, the Controllable and Uncontrollable groups received an identical set of thermal stimuli but differed in the feedback they received indicating whether or not they had controlled the duration of the thermal stimuli.

In order to control for potential group differences in pain response and response to failure feedback, we ensured that all participants in the controllable group had the same number of initial failure trials. This was done as follows: unbeknownst to participants in the Controllable group, the “correct” response button sequence was determined by the first novel response following the 12th trial. This allowed an initial set of trials (which included five 5-second stimuli – see Figure 1c) on which participants in both groups received identical thermal stimuli and identical feedback indicating that they had failed to control the length of the heat. These initial trials in which both groups received failure feedback are hereafter referred to as “matched trials”. Subsequent trials in which thermal stimuli were identical but the feedback provided was different (contingent participants in the Controllable group making the correct response) are referred to as “unmatched trials” (this set of trials included 20 five-second trials – see Figure 1c). Thus, the 50 total trials included both an initial set of matched trials and a subsequent set of unmatched trials. In order to maintain the illusion that repeating the correct sequence would always shorten the heat, no 10-second heat bursts were given following the 12th trial. There was minimal variation in the number of trials needed to achieve a first novel and successful button response: all participants in the controllable group made a novel response between the 5th and 6th five second stimuli (corresponding to the last five-second trial of the matched set and the first five-second trial of the unmatched set).

The analytic focus of the experiment for both region-of-interest and whole brain analyses was the medium (5s) trials, as participants in the Controllable group were led to believe that they had successfully reduced a long stimulus, while participants in the Uncontrollable group believed they had failed to reduce the medium stimuli to short ones. There were five medium-length stimuli during the matched period and twenty medium-length stimuli during the unmatched period (see Figure 1c). All subsequent analyses and references to painful stimuli will refer to these 5s medium trials. We use the label “Time” for this variable to reflect the fact that all matched trials occurred prior to the controllable group receiving feedback that they had discovered the correct response pattern.

The state anxiety portion of the State-Trait State Anxiety Inventory (STAI - (Spielberger, Gorsuch, & Lushene, 1970) was administered immediately before and immediately after the scanning session. The variable created by residualizing scores on the “after” questionnaire with respect to the “before” questionnaire will hereafter be referred to as “state anxiety change”. Residualized scores were used for all difference scores (including reaction time and pain intensity) instead of simple difference scores as previous research (Williams & Zimmerman, 1982) suggests that residualized scores are more reliable when the ratio of standard deviations of early to late trials is greater than the correlation between early and late trials, which was found to be the case in the present study for state anxiety. Results did not change substantively if simple difference scores were used. One subject in the controllable group did not provide state anxiety data, thus analyses of state-related changes in anxiety are conducted on the 51 remaining participants.

Following testing, participants completed a questionnaire which assessed their understanding of the task, motivation, degree of engagement, perceived control and attributions for success/failure using a series of structured and unstructured questions. Each item was administered on a five-point likert scale.

Analyses of all behavioural data and correlations with extracted neural data (see below) was conducted in SPSS (Chicago, IL). Group * time interactions in dependent measures (state anxiety, neural activation in regions of interest) were analyzed with group (UC vs C) as a between-subjects factor and time as a repeated measures factor (pre vs. post experiment for state anxiety and matched 5-sec trials vs. Unmatched 5-sec trials for all variables). Between group comparisons (e.g. group differences in post-testing questionnaire data) were conducted using a one-way ANOVA with group as a factor. Within-group analyses (e.g. comparing state-related changes in self reported anxiety) were run as repeated measures ANOVAs. P<0.05 (two-tailed) was used as the a priori significance level for all analyses.

fMRI Image Acquisition

Images were acquired on a General Electric Signa 3.0 Tesla high speed imaging device with a quadrature head coil. Functional images consisted of 30 × 4 mm sagittal EPI slices covering the whole brain (1 mm interslice gap; 64×64 in-plane resolution, 240 mm FOV; TR/TE/Flip = 2000 ms/30 ms/90; 225 image volumes per run). Immediately preceding acquisition of functional images, a whole brain high-resolution T1-weighted anatomical scan (3D T1-weighted inversion recovery fast gradient echo; 256×256 in-plane resolution, 240 mm FOV; 124 × 1.2 mm axial slices) was acquired. Functional images were collected in 5 scan runs, 7 minutes and 30 seconds per run.

fMRI Image Analysis

Data preprocessing consisted of slice time correction and motion correction using AFNI (Cox, 1996). All other analyses were carried out using FEAT (Beckmann, Jenkinson, & Smith, 2003) (FMRI Expert Analysis Tool), part of FSL (FMRIB's Software Library, www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl). Data were smoothed with a 5 mm FWHM Gaussian blur and high pass filtered with a 100 second cut-off. Five volumes were dropped at the beginning of the experiment for signal stabilization.

Data were analyzed in two steps. In the first general linear model (at the individual subject level), a separate regressor for each experimental condition (the cue, the 3s anticipatory period, the rating screen and the short, medium and long pain stimuli, with matched and unmatched 5s medium pain stimuli modelled separately) was derived by convolving a stimulus-based binary boxcar function (from onset to offset of the experimental condition) with an ideal hemodynamic response. Main effect analyses of controllability were assessed from the results of this individual subject level GLM.

To examine psychophysical interactions (PPI - Friston et al., 1997) with our regions of interest, the fMRI time series was extracted from the seed region for each subject and this time series was entered as a regressor along with all events modelled in the experiment. A regressor representing the interaction of the seed time series with the unmatched pain regressor was also run to examine which regions of the brain differed in their connectivity with the seed region as a function of pain. Additionally, scan runs and 6 motion covariates (I-S, L-R, A-P, pitch, yaw and roll) were included as nuisance variables. The time series data for each voxel were then modelled as the linear sum of all regressors. Data were registered to MNI space using FLIRT.

Region of Interest (ROI) Analysis

The primary goal of ROI analysis was to examine the role of two a priori regions of interest (amygdala and NAcc) in processing the effects of perceived control on state anxiety change. In line with this goal we extracted values from anatomically-defined amygdala and NAcc seeds. Regions of interest were generated by creating a mask of these regions from the Harvard Oxford Subcortical Structural Atlas. Probability maps were thresholded such that every voxel within the mask had at least an 80% chance of being within the structure. This mask was then used to extract values from the appropriate contrast maps (see below). We first examined the main effects of perceived control on activation in these regions, analyzing extracted values by group (UC vs. C) and at single time points (Matched vs Unmatched trials), as well as group * time interactions in SPSS. We were also interested in patterns of connectivity that underlie state anxiety change when participants perceived control. We therefore conducted a voxel wise GLM within the Controllable group to search for regions where altered connectivity with the seed regions during pain (the output of the interaction term in the first GLM) was significantly associated with state anxiety change.

Contrasts at group and individual level are provided as z-scores. For all neuroimaging analyses, a cluster-wise correction for multiple comparisons (z=2.3, p<0.05, Gaussian Random Field Theory) was used, unless otherwise noted.

Whole brain main effect analyses of pain and controllability

The neural response to painful stimulation has been well delineated and has been the subject of both quantitative (Farrell, Laird, & Egan, 2005) and qualitative (Peyron, Laurent, & Garcia-Larrea, 2000) meta-analyses. Several regions, including the anterior cingulate, insula, secondary somatosensory cortex, and thalamus are consistently activated when participants are exposed to painful experimental stimuli (Johnstone, Salomons, Backonja, & Davidson, 2012). As a measure of data quality we conducted an analysis to ensure that our findings were concordant with this literature. The pain related activations presented in Table 1b and Figure 5 are regions that were significantly activated in both the Controllable and Uncontrollable group on the twenty “Unmatched” 5-second stimuli (see Table 1b and Figure 5).

Table 1B. Activation in pain-related regions.

To examine consistent responses to painful stimuli, we broke the 25 five-second stimuli into five sets. The following regions were significant in all five sets, and also during presentation of ten-second stimuli following the experiment (which was presented without visual stimuli, to mask out regions associated with viewing feedback stimuli). Mean Z-statistics represent the mean of activation in all those conditions.

| REGION | XYZ | Mean Z-statistic |

|---|---|---|

| Anterior Cingulate Gyrus (BA32)/SMA (BA6) | 2, 14, 38 | 7.08 |

| Insular Cortex (BA13) | 36, 8, 6 | 10.13 |

| 40, -14, 14 | 9.77 | |

| -36, 4, 6 | 8.31 | |

| Thalamus | 8, -12, 0 | 6.85 |

| -10, -12, 2 | 4.3 | |

| Inferior Parietal Lobe (BA40) | 62, -20, 20 | 8.66 |

| Middle Frontal Gyrus (BA 9/6) | 44, 8, 36 | 5.76 |

| Middle Frontal Gyrus (BA 46) | 42, 40, 16 | 6.24 |

| Inferior Frontal Gyrus (BA10) | 42, 44, 4 | 6.33 |

| Fusiform Gyrus | 26, -78, -12 | 8.46 |

| -18, -82, -16 | 8.90 | |

| Putamen | 22, 10, -4 | 4.87 |

| Lingual Gyrus | 4, -88, 0 | 8.5 |

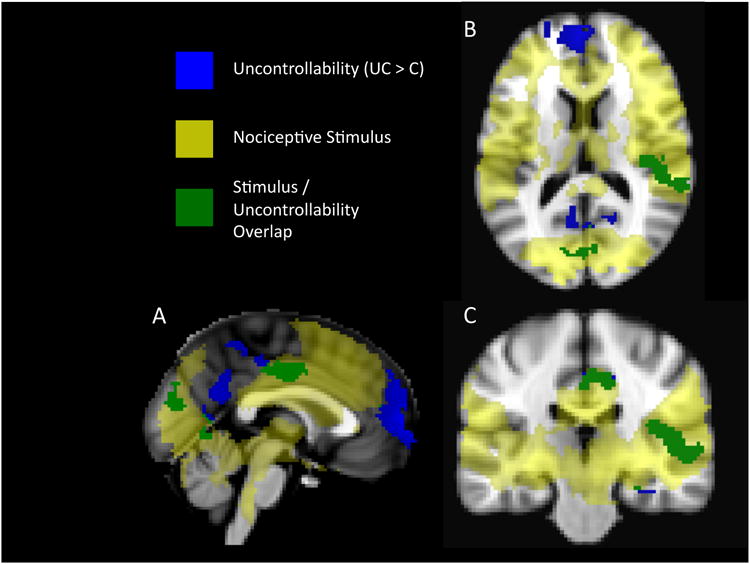

Figure 5. Activation associated with nociceptive stimulation, controllability and their overlap.

Activations in yellow are regions that were activated by the 5-second nociceptive stimuli in both Uncontrollable and Controllable groups. Activations in blue are regions where uncontrollable pain elicited significantly more activation in the Uncontrollable group. Regions in green were significantly activated in both conditions, but significantly more active in the Uncontrollable condition.

For the purpose of comparison with previous studies of the effects of perceived control on pain (Salomons, 2004; Wiech, 2006), the results of whole brain analyses comparing “Unmatched” pain trials between the Uncontrollable group to the Controllable group are also reported (UC>C). Paralleling the analysis method used in our previous published work (Salomons et al, 2004), we report the main effects of perceived control (UC>C) as well as the stimulus/controllability overlap (regions activated in both conditions, but more significantly activated in the uncontrollable condition).

Results

Consistent with expectation, the Controllable group reported greater perceived control than the Uncontrollable group (M/SD=3.3/1.3 for C, 1.7/1.2 for UC; F(1, 50) = 20.7, p<0.05) on the post-testing questionnaire. The groups did not differ in the degree to which they found the task boring (M/SD=2.5/0.8 for C; 2.2/1.0 for UC) or their self reported level of motivation following the experiment (M/SD=4.7/0.6 for C, 4.3/0.9 for UC).

A repeated measures ANOVA indicated a significant group × time interaction in state anxiety, F(1, 49)=14.2, p<0.05. Consistent with our hypothesis that exposure to uncontrollable stress would elicit anxiety, the uncontrollable group reported more anxiety following the experiment (pre M/SD 31.48/5.02, post 34.62/7.15; paired t1, 28 = 2.76, p<0.05), while the controllable group reported less anxiety (pre M/SD 33.14/6.35, post 29.09; paired t1, 21=-2.53, p<0.05). There was no significant group difference on pre-experiment state anxiety, (F1, 49=1.08, p=0.30) but the post-experiment difference was significant (F1, 49=10.26, p<0.05).

There was a significant group by time interaction in self-reported pain intensity ratings (F1, 50=5.02, p=0.03) such that the Controllable group experienced a more pronounced increase in pain (mean/sd matched trials = 4.93/1.15, unmatched trials 6.23/1.54, t=6.28, p<0.01) than the Uncontrollable group (mean/sd matched trials = 4.79/1.39, unmatched trials 5.49/1.41, t=4.09, p<0.01) – See Figure 4). There was also a trend towards a significant difference between groups in pain intensity ratings on unmatched trials (F=3.19, p=0.08). There was no relationship between pain intensity and state anxiety (r=-0.09, p=0.54). There was no Group by Time interaction in pain unpleasantness ratings, F(1, 50)=0.67, p=0.42).

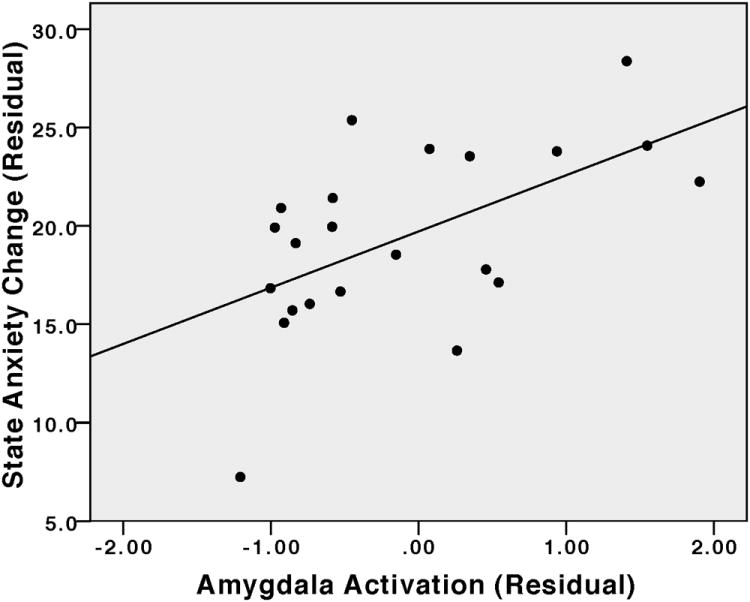

Figure 4. Amygdala activation vs state anxiety change in the controllable group.

Post scan state anxiety is residualized with respect to pre scan anxiety. Amygdala activation on unmatched trials is residualized with respect to activation on matched trials.

There was a significant Group by Time interaction in reaction time (RT), F(1, 50)=64.6, p<0.01. Compared to the matched trials, the Uncontrollable group's reaction time on the unmatched trials increased and the Controllable group's reaction time decreased (Controllable group mean/sd in milliseconds pre-experiment = 2808.57/480.79, post-experiment 2023.54/314.33; Uncontrollable group mean/sd in milliseconds pre-experiment 2603.94/728.53, post-experiment 2757.29/660.77). There was no significant group difference in reaction time on the matched trials (F1, 50=1.35, p=0.25). Reaction times may be understood as an indirect proxy for task engagement, as longer reaction times in the Uncontrollable group likely reflect ongoing uncertainty about the response required to shorten the nociceptive stimulus in the wake of negative feedback. Reaction time change negatively correlated with pain intensity ratings (r=-0.34, p=0.02) and self reported perceived control (r=-0.42, p<0.01). These findings indicate that engagement in the task appeared to result in reduction of perceived pain intensity.

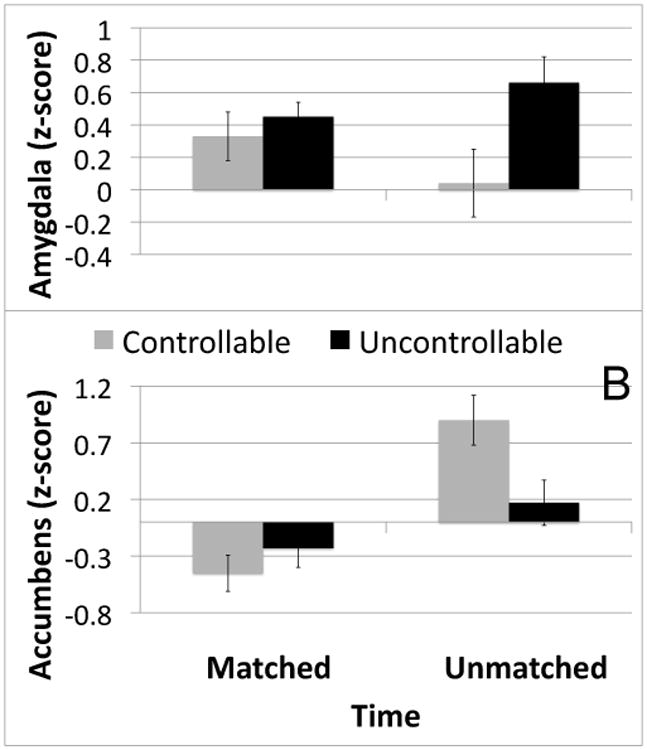

Region of Interest Analyses: Neural circuits underlying anxiolytic effects of controllability

A repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant group by time interaction for bilateral amygdala (F1, 50=4.02, p=0.05). Follow-up tests demonstrated significantly more activation in the uncontrollable group in the amygdala on unmatched trials (F1, 50=5.88, p<0.05; see Figure 2a). There was no difference in amygdala activation between the groups on matched trials (F1, 50=0.59, p=0.45). Within the Controllable group, amygdala activation was significantly correlated with state anxiety such that reduction in amygdala activation (unmatched trials residualized with respect to matched trials) was associated with reduced state anxiety (post-testing STAI residualized with respect to pre-testing STAI; r=0.56, p<0.05).

Figure 2. Group × Time Interaction for Amygdala (A) and Nucleus Accumbens (B) activation.

The group × time interaction was significant for anatomically defined clusters in both amygdala (F1, 50=4.02, p=0.05) and nucleus accumbens (F1, 50=5.95, p<0.05). Groups did not differ on matched trials for either region.

A repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant group × time interaction for the bilateral nucleus accumbens (F1, 50=5.95, p<0.05; see Figure 2b). There was significantly more NAcc activation in the controllable group on unmatched trials (F1, 50=5.95, p<0.05). There was no difference between the groups on matched trials (F1, 50=-0.85, p=0.36). NAcc activation was correlated with state anxiety change within the Controllable group (r=0.6, p<0.05) such that higher NAcc activation was associated with higher state anxiety. This correlation was not significant after accounting for a single outlier >2SD from the mean in state anxiety change and will therefore not be discussed further. Accounting for this outlier (as well as one similar outlier in the UC group) did not affect the significance or direction of any of the other results in this report.

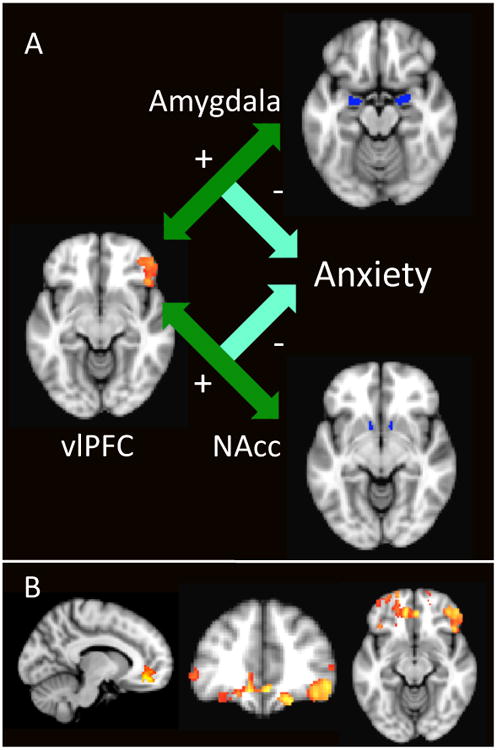

A PPI analysis was conducted to look for regions where altered connectivity with amygdala and NAcc during pain predicted state anxiety change in the Controllable group. Increased functional connectivity between bilateral NAcc and several prefrontal regions was significantly associated with reduced state anxiety. These regions included the ventral medial prefrontal cortex (BA10/32) and bilateral ventral lateral/orbitofrontal cortex (BA 11/44/45/47).

Increased functional connectivity between bilateral amygdala and right ventral lateral/orbitofrontal PFC (BA11/44/45/47; peak 48, 34,-10; see Figure 3a) was significantly associated with reduced state anxiety This ventral lateral/orbitofrontal PFC region (hereby “vlPFC”) largely overlapped with the corresponding PFC cluster in the NAcc map. The correlation between state anxiety reduction and connectivity between this overlapping vlPFC cluster and the amygdala (r=-0.69) was significantly stronger than the corresponding correlation in the Uncontrollable group (UC r=-0.33, p=ns; z for difference between correlations =-1.67, p<0.05). Similarly, the association between state anxiety change and NAcc-vlPFC connectivity (r=-0.74) was significantly stronger than in the Uncontrollable group (UC r=0.03, p=ns; z for difference between correlations =-3.25, p<0.05). While these findings suggest that the relationship between anxiety and PFC to amygdala, and anxiety and PFC to NAcc connectivity might be unique to controllable stress, they should be interpreted with caution. Specifically, the connected regions were derived from a voxel-wise search within the controllable group and thus may result in a bias towards that group. There was no group difference in the mean level of connectivity between the amygdala and vlPFC (F1, 50=0.03, p=0.87) or between NAcc and vlPFC (F1, 50=0.01, p=0.94).

Figure 3. A) Functional Connectivity of vlPFC with Amygdala and Nucleus Accumbens Predicts State Anxiety Change.

Anatomically-defined Amygdala and Nucleus Accumbens clusters were used as seeds in PPI analysis. Maps of regions whose connectivity with the ROI was associated with reduced anxiety were generated. The region of vlPFC pictured represents the overlap of the Amygdala and Nucleus Accumbens map, such that increased functional connectivity of vlPFC with both regions (indicated by the green arrow) significantly predicted reduced anxiety (r=-0.67 for Amygdala, r=-0.74 for NAcc). Z=2.3 (p<0.05, corrected)

B) Extended Map of Amygdala and Nucleus Accumbens Connectivity Overlap

To investigate an a priori hypothesis about involvement of vmPFC, we examined regions where increased connectivity of both Amygdala and Nucleus Accumbens predicted reduced state anxiety change at a lower threshold of z=1.96 (p<0.05, corrected). Images are shown at the peak voxel (z=4.0) for vmPFC.

While connectivity between amygdala and vmPFC did not meet our a priori threshold for significance (z=2.3, p<0.05 corrected), given the demonstrated involvement of vmPFC in mediating the beneficial effects of perceived control and, more generally, in interacting with amygdala to regulate negative affect (Urry et al., 2006), we were interested in investigating the role of this region. We re-ran the analysis at a reduced voxel wise threshold while still applying correction for multiple comparisons (z=1.96, p<0.05, corrected). At this level, connectivity between amygdala and both vmPFC and left vlPFC was significantly associated with state anxiety change. This map largely overlapped the NAcc connectivity mask (see Figure 3b for overlap). Increased connectivity between vmPFC and amygdala was correlated with state anxiety reduction in the Controllable group (r=-0.7). This relationship was non-significant in the Uncontrollable group (r=-0.14, p=0.49) and significantly weaker than the Controllable group (z=-2.41, p<0.05). Similarly, increased vmPFC-NAcc connectivity was associated with state anxiety reduction in the Controllable (r=-0.7) but not Uncontrollable group (r=0.17, p=0.37). This difference was significant (z=-3.44, p<0.05). While the focus of this report is the right vlPFC region that met our a priori threshold in both maps, these results nevertheless indicate that functional connectivity between the two seed regions and ventral lateral PFC is bilateral. Furthermore, they confirm the role of vmPFC in the anxiolytic effects of perceived control.

Whole Brain Analyses: Effects of Perceived Control

The Uncontrollable group displayed significantly more activation during the pain stimuli on the unmatched trials, compared to the Controllable group, in a number of regions (Table 1a). These included regions such as the thalamus, insula and anterior cingulate that are commonly activated in pain, reinforcing our previous finding (Salomons et al, 2004) that perceived control reduces activation within regions commonly associated with pain when control is perceived. We also observed activation differences (UC>C) in posterior cingulate cortex as well as a region of parietal cortex (BA7) that has been linked with the integration of visual and somatosensory input in threat assessment (Dong, Chudler, Sugiyama, Roberts, & Hayashi, 1994; Robinson & Burton, 1980). There were no activation differences (C>UC) that survived correction for multiple comparisons at the whole brain level.

Table 1A. Significant Activations in Group Contrast (UC-C).

Regions surviving the cluster-based correction for multiple comparisons in the group contrast (uncontrollable>controllable). Coordinates are in MNI space.

| REGION | XYZ | Z-Score Max Voxel |

|---|---|---|

| Medial Frontal Gyrus (BA 9/10) “mPFC” | 0, 60, 8 | 5.15 |

| Posterior Cingulate Gyrus (BA 23) | 0, -54, 24 | 3.98 |

| Superior/Middle Frontal Gyrus (BA 8) “dlPFC” | -22, 32, 32 | 3.66 |

| Anterior Cingulate Gyrus (BA24) “ACC” | 0, -12, 36 | 4.37 |

| Cuneus (BA 19) | 20, -82, 38 | 3.27 |

| Lingual Gyrus | 22, -62, -4 | 3.59 |

| -12, -56, -2 | 3.87 | |

| Lingual/Parahippocampal Gyrus | 28, -40-8 | 3.02 |

| Fusiform Gyrus (BA37) | 42, -48, -16 | 3.71 |

| Superior Temporal Gyrus | 56, -22, 0 | 2.86 |

| Thalamus | -20, -32, 0 | 2.65 |

| Hippocampus | 28, -20, -18 | 5.15 |

Correlations Between Activation and Behavioral Measures

Increased activation in mPFC was also associated with longer reaction time (r=0.34, p=0.01). Within the uncontrollable group, higher activation in mPFC was associated with increased anxiety (r=0.4, p=0.04).

Discussion

These data provide evidence for the anxiolytic effects of perceived control over a stressor. Participants who perceived control over pain experienced a significant reduction in state anxiety compared to participants who did not. Participants who perceived control also had reduced activation in the amygdala and increased activation in nucleus accumbens. In participants who perceived control, these anxiolytic effects were associated with increased functional connectivity of amygdala and NAcc with both vlPFC and vmPFC

The amygdala's involvement in the encoding of affective significance and in emotional learning and expression is well documented (Davis & Whalen, 2001; Phelps & LeDoux, 2005; Morrison & Salzman, 2010). Of particular relevance to the present findings are data linking dysregulated amygdalar activation with anxiety disorders (Bishop, 2007; Shin & Liberzon, 2010) and behavioral inhibition (Oler et al., 2010). Animal and human work has focused on the role of prefrontal regions in regulating amygdala responses and the lack of a regulatory relationship between the PFC and amygdala has been observed in major depressive disorder (T. Johnstone et al., 2007). Consistent with this literature, studies in which participants are asked to reappraise aversive stimuli consistently observe a regulatory relationship between prefrontal regions and the amygdala (Ochsner & Gross, 2005), with the vlPFC most frequently implicated (Ochsner et al., 2002; Schaefer et al., 2002; T. Johnstone et al., 2007; Goldin et al., 2008). Consistent with the role of amygdala in negative affect, we observed reduced activation in amygdala when individuals perceived control and a positive relationship between amygdala activation and state anxiety change. The amygdala has also been demonstrated to underlie reappraisal of both pain and other elicitors of negative affect within individuals (Lapate et al., 2012). Our finding that increased connectivity of amygdala and vlPFC was associated with reduced anxiety when participants perceived control is consistent with previous observations linking interactions between these regions in regulating negative affect.

In addition to the previously observed role of vlPFC-amygdala interactions, it has been hypothesized that striatal regions play a role in processing affective responses to choice and perceived control (Leotti et al., 2010). Furthermore, Wager and colleagues (Wager et al., 2008) suggested a role for one particular region of the striatum, the nucleus accumbens, in cognitive regulation of negative affect, with vlPFC up-regulating the nucleus accumbens during reappraisal of negative affect. This region is frequently associated with reward processing and reward-related affect (Haber & Knutson, 2010), leading to the hypothesis that its role in volitional control of negative emotion is increasing positive affect in parallel with amygdala-related reduction of negative affect (Wager et al., 2008). Our finding that perceived control was associated with increased activation of NAcc and that connectivity between NAcc and right vlPFC was associated with decreased state anxiety in participants who perceived control is consistent with evidence that perceived control is inherently rewarding and motivational (Leotti & Delgado, 2011). These rewarding properties may therefore contribute to the anxiolytic effects of control. While perceiving a sense of control over one's environment might be inherently rewarding, it should be noted that the current study design does not allow the effects of perceived control and reward to be disentangled, as perceived control was delivered in the form of success feedback which was likely perceived as rewarding.

There was a high degree of overlap in regions of the prefrontal cortex showing anxiety-related functional connectivity changes with the amygdala and NAcc. In particular, increased connectivity between the amygdala and the NAcc and both the vlPFC and vmPFC was associated with reduced anxiety. This is consistent with a large body of literature documenting the role of these prefrontal regions in processing the effects of perceived control and in emotion regulation more generally. The vmPFC has been demonstrated to play a role in distinguishing between uncontrollable and controllable stress, and mediating the anxiolytic effects of the latter. Furthermore, covariation between vmPFC and amygdala has been associated with extinction of fear (Quirk & Beer, 2006; Urry et al., 2006; Delgado, Nearing, Ledoux, & Phelps, 2008), although rodent studies strongly suggest that the role of vmPFC in the anxiolytic effects of perceived control is an expression of fear rather than altered learning (Baratta, Lucero, Amat, Watkins, & Maier, 2008). Furthermore, similar effects are observed if vmPFC is activated during the expression of fear even in the absence of perceived control. Collectively, these findings suggest that the anxiolytic effects of perceived control are not mediated by a dedicated neural circuit but utilize a more general regulatory mechanism.

Consistent with this assertion, a striking finding of this study is how similar the neural mechanisms of the anxiolytic effects of perceived control are to those observed in previously published reports of reappraisal of negative emotion. More specifically, we found that functional connectivity of both amygdala and NAcc with vlPFC, a circuit implicated in the reduction of negative affect by reappraisal (Wager et al., 2008) and compassion training (Weng et al., 2013), was associated with reductions in state anxiety when participants had perceived behavioral control over the duration of the pain stimuli, but no such relationship existed for participants who did not perceive control. Averill (Averill, 1973) has distinguished between behavioral control (where individuals perceive the availability of a behavioral response which will remove or modify a stressor) and cognitive control (where individuals alter their evaluation of a stressor to reduce their stress response). Optimal coping with stress is thought to involve both forms of control, with cognitive control hypothesized to be an adaptive response when no behavioral options for controlling stress are available (Carver, Scheier, & Weintraub, 1989). These data put this assertion in new light by suggesting that optimal regulation of negative affect depends on the ability to find a situationally appropriate means of activating a common regulatory circuit.

Pain perception and the Effect of Controllability

Anxiety has commonly been found to exacerbate the experience of pain (Keefe et al., 2004). The finding that the Uncontrollable group reported a significantly smaller increase in pain, despite increased anxiety is therefore somewhat counterintuitive. In instances of extreme anxiety, stress induced analgesia has been observed (Amit & Galina, 1986), but given the relatively low levels of anxiety elicited and the fact that anxiety and pain intensity were uncorrelated, it would seem unlikely that the observed result is due to stress-induced analgesia.

A more likely explanation for this finding is that on the unmatched trials (following the Controllable group finding the correct pattern), the Uncontrollable group was more engaged in the cognitive task of identifying the correct pattern of button presses and therefore more distracted from the pain stimulus than the Controllable group. Higher engagement throughout the task in the Uncontrollable group is supported by significantly longer reaction times on the unmatched trials in that group. Longer reaction times indicate a combination of continued effort and uncertainty, as participants who had either figured out the correct pattern or given up serious efforts to figure out the pattern would be expected to respond more quickly. Given that feedback about the correctness of the response was coincident with the pain stimuli, it is likely that participants who remained engaged in the task would be actively evaluating their previous responses and perhaps formulating future responses during the pain stimuli, a process that likely distracted from the coincident sensory input. The possibility that this process might have distracted participants from the sensory aspects of the pain stimuli is consistent with the observed correlation between reaction time and pain intensity ratings, such that slower reaction times (indicative of greater task engagement) were associated with decreased pain ratings.

An attentional interpretation of this finding is also consistent with the fact that differences were observed between the groups in intensity, rather than unpleasantness. Two studies examining the differential impact of emotion and attention on pain (Villemure & Bushnell, 2002; Villemure & Bushnell, 2009) report that emotional modulation of pain differentially affects pain unpleasantness, while attentional modulation affects pain intensity.

This interpretation casts new light on previous findings regarding the effects of perceived control on pain perception and neural activation. A previous within-participants study found widespread increases throughout the so-called “pain matrix” when pain was perceived as uncontrollable, although these activation increases were not associated with increased pain perception (Salomons et al, 2004). This 2004 study diverged from a subsequent study by Wiech et al (2006) which found increased activation in regions such as the ACC in the controllable (rather than uncontrollable) condition, as well as reduced pain perception in the controllable condition. These divergent findings can be reconciled using more recent work suggesting that activation within the “pain matrix” is largely unspecific for pain and rather has to do with the salience of the stimulus – the degree to which the stimulus captures attention and/or compels action

In the experiment by Wiech and colleagues, participants were asked to stop the stimuli in the controllable condition when they could no longer tolerate the pain, likely drawing their attention towards the pain in that condition and increasing pain perception. In this case, behavioural demands of the task likely drew attention to the pain stimulus in the controllable condition. In the 2004 study by Salomons et al, behavioural demands of the task were matched, but a cue preceding the pain drew subject attention towards the fact that the subsequent stimulus would be uncontrollable, likely increasing the salience of the stimulus in that condition. The current study partially replicates this latter finding, showing increased activation in “pain matrix” regions (anterior cingulate and insula), but these activations are notably less widespread than in the 2004 study. Within the context of the work on salience discussed above, a likely explanation is that while overall the uncontrollable condition might have been more behaviorally demanding (as evidenced by longer reaction times) and therefore more salient overall, these behavioural demands competed with sensory input for attention, reducing activation in this “salience” network and resulting in the relatively small net increase in salience regions. This draws fresh attention to an often-overlooked aspect of the perceived controllability literature, namely the demands that are placed on an individual seeking to re-gain control. These data suggest that it is not only the cognitive state of having control that is relevant to pain perception and corresponding brain activation, but that the behavioral demands of regaining control that may be of relevance. Future work should focus on examining how the interaction or perceived control and task difficulty (or the degree to which the task draws attention away from sensory input) affects pain perception and associated neural activation.

Conclusion

In summary, we found that when participants perceived that they had successfully exerted control over a series of painful stimuli, they experienced reductions in state anxiety and amygdala activation and increased activation in the nucleus accumbens. In participants who perceived control over the painful stimuli, increased functional connectivity between each of these subcortical regions and both ventral lateral and ventral medial prefrontal cortex was associated with decreased state anxiety. Based on the observed similarity between this anxiolytic circuitry and findings of previous studies of negative affect reduction through reappraisal, it is suggested that perceived control reduces anxiety by recruiting a general emotion regulation circuit.

Additionally, our finding partially replicate previous findings of increased activation in salience regions (e.g. ACC, insula) when pain is uncontrollable. While both groups experienced an increase in pain intensity as the experiment continued, this increase was significantly smaller in the Uncontrollable group. As pain intensity was unrelated to anxiety, it is likely that this difference was the result of distraction due to higher task engagement in the Uncontrollable group, calling attention to the importance of examining task demands in perceived control experiments prior to attributing activation solely to agency beliefs.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank JJ Curtin, JB Nitschke, JP Newman, MM Backonja and LY Abramson for helpful comments. This study was supported by National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) grants R01-MH43454 and P50-MH069315 to R.J.D, a gift from William Heckrodt and a Clinician-Scientist Award from the University of Toronto Centre for the Study of Pain to T.V.S.

References

- Amat J, Baratta MV, Paul E, Bland ST, Watkins LR, Maier SF. Medial prefrontal cortex determines how stressor controllability affects behavior and dorsal raphe nucleus. Nature Neuroscience. 2005;8(3):365–371. doi: 10.1038/nn1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arntz A, Schmidt AJM. Stress, personal control and health. Oxford: Stress, personal control and health; 1989. Perceived control and the experience of pain; p. 131. [Google Scholar]

- Averill JR. Personal control over aversive stimuli and its relationship to stress. Psychological Bulletin. 1973;80(4):286–303. [Google Scholar]

- Baratta MV, Lucero TR, Amat J, Watkins LR, Maier SF. Role of the ventral medial prefrontal cortex in mediating behavioral control-induced reduction of later conditioned fear. Learning & Memory (Cold Spring Harbor, NY) 2008;15(2):84–87. doi: 10.1101/lm.800308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckmann CF, Jenkinson M, Smith SM. General multilevel linear modeling for group analysis in FMRI. NeuroImage. 2003;20(2):1052–1063. doi: 10.1016/S1053-8119(03)00435-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop SJ. Neurocognitive mechanisms of anxiety: an integrative account. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2007;11(7):307–316. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Scheier MF, Weintraub JK. Assessing coping strategies: a theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;56(2):267–283. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.56.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox RW. AFNI: software for analysis and visualization of functional magnetic resonance neuroimages. Computers and Biomedical Research, an International Journal. 1996;29(3):162–173. doi: 10.1006/cbmr.1996.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M, Whalen PJ. The amygdala: vigilance and emotion. Molecular Psychiatry. 2001;6(1):13–34. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado MR, Nearing KI, Ledoux JE, Phelps EA. Neural circuitry underlying the regulation of conditioned fear and its relation to extinction. Neuron. 2008;59(5):829–838. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong WK, Chudler EH, Sugiyama K, Roberts VJ, Hayashi T. Somatosensory, multisensory, and task-related neurons in cortical area 7b (PF) of unanesthetized monkeys. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1994;72(2):542–564. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.2.542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell MJ, Laird AR, Egan GF. Brain activity associated with painfully hot stimuli applied to the upper limb: a meta-analysis. Human Brain Mapping. 2005;25(1):129–139. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friston KJ, Buechel C, Fink GR, Morris J, Rolls E, Dolan RJ. Psychophysiological and modulatory interactions in neuroimaging. NeuroImage. 1997;6(3):218–229. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1997.0291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin PR, McRae K, Ramel W, Gross JJ. The neural bases of emotion regulation: reappraisal and suppression of negative emotion. Biological Psychiatry. 2008;63(6):577–586. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haber SN, Knutson B. The reward circuit: linking primate anatomy and human imaging. Neuropsychopharmacology: Official Publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35(1):4–26. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone T, van Reekum CM, Urry HL, Kalin NH, Davidson RJ. Failure to regulate: counterproductive recruitment of top-down prefrontal-subcortical circuitry in major depression. The Journal of Neuroscience : the Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2007;27(33):8877–8884. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2063-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone Tom, Salomons TV, Backonja MM, Davidson RJ. Turning on the alarm: the neural mechanisms of the transition from innocuous to painful sensation. NeuroImage. 2012;59(2):1594–1601. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.08.083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalisch R. The functional neuroanatomy of reappraisal: time matters. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2009;33(8):1215–1226. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapate RC, Lee H, Salomons TV, van Reekum CM, Greischar LL, Davidson RJ. Amygdalar function reflects common individual differences in emotion and pain regulation success. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2012;24(1):148–158. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_00125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS. Stress and Emotion: A New Synthesis. New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, Appraisal and Coping. New York: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Leotti LA, Delgado MR. The Inherent Reward of Choice. Psychological Science. 2011 doi: 10.1177/0956797611417005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leotti LA, Iyengar SS, Ochsner KN. Born to choose: the origins and value of the need for control. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2010;14(10):457–463. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier SF, Watkins LR. Stressor controllability and learned helplessness: the roles of the dorsal raphe nucleus, serotonin, and corticotropin-releasing factor. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2005;29(4-5):829–841. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier SF, Watkins LR. Stressor controllability, anxiety, and serotonin. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1998;22(6):595–613. [Google Scholar]

- Maier Steven F, Seligman ME. Learned helplessness: Theory and evidence. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1976;105(1):3–46. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.105.1.3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mineka S. Controllability and Predictability in Acquired Motivation. Annual Review of Psychology. 1985;36:495–529. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.36.020185.002431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison SE, Salzman CD. Re-valuing the amygdala. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2010;20(2):221–230. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochsner KN, Bunge SA, Gross JJ, Gabrieli JD. Rethinking feelings: an FMRI study of the cognitive regulation of emotion. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2002;14(8):1215–1229. doi: 10.1162/089892902760807212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochsner KN, Gross JJ. The cognitive control of emotion. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2005;9(5):242–249. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochsner KN, Ray RD, Cooper JC, Robertson ER, Chopra S, Gabrieli JD, Gross JJ. For better or for worse: neural systems supporting the cognitive down- and up-regulation of negative emotion. NeuroImage. 2004;23(2):483–499. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oler JA, Fox AS, Shelton SE, Rogers J, Dyer TD, Davidson RJ, et al. Kalin NH. Amygdalar and hippocampal substrates of anxious temperament differ in their heritability. Nature. 2010;466(7308):864–868. doi: 10.1038/nature09282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyron R, Laurent B, Garcia-Larrea L. Functional imaging of brain responses to pain. A review and meta-analysis (2000) Neurophysiologie Clinique = Clinical Neurophysiology. 2000;30(5):263–288. doi: 10.1016/s0987-7053(00)00227-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelps EA, LeDoux JE. Contributions of the amygdala to emotion processing: from animal models to human behavior. Neuron. 2005;48(2):175–187. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quirk GJ, Beer JS. Prefrontal involvement in the regulation of emotion: convergence of rat and human studies. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2006;16(6):723–727. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson CJ, Burton H. Somatic submodality distribution within the second somatosensory (SII), 7b, retroinsular, postauditory, and granular insular cortical areas of M. fascicularis. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1980;192(1):93–108. doi: 10.1002/cne.901920106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomons TV. Perceived controllability modulates the neural response to pain. Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;24:7199–7203. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1315-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomons TV, Johnstone T, Backonja MM, Shackman AJ, Davidson RJ. Individual differences in the effects of perceived controllability on pain perception: critical role of the prefrontal cortex. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2007;19(6):993–1003. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2007.19.6.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer SM, Jackson DC, Davidson RJ, Aguirre GK, Kimberg DY, Thompson-Schill SL. Modulation of amygdalar activity by the conscious regulation of negative emotion. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2002;14(6):913–921. doi: 10.1162/089892902760191135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin LM, Liberzon I. The neurocircuitry of fear, stress, and anxiety disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology: Official Publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35(1):169–191. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene RE. The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory: Test Manual. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologist Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson SC. Will it hurt less if i can control it? A complex answer to a simple question. Psychological Bulletin. 1981;90(1):89–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urry HL, van Reekum CM, Johnstone T, Kalin NH, Thurow ME, Schaefer HS, et al. Davidson RJ. Amygdala and ventromedial prefrontal cortex are inversely coupled during regulation of negative affect and predict the diurnal pattern of cortisol secretion among older adults. The Journal of Neuroscience : the Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2006;26(16):4415–4425. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3215-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wager TD, Davidson ML, Hughes BL, Lindquist MA, Ochsner KN. Prefrontal-subcortical pathways mediating successful emotion regulation. Neuron. 2008;59(6):1037–1050. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss JM, Stout JC, Aaron MF, Quan N, et al. Depression and anxiety: Role of the locus coeruleus and corticotropin-releasing factor. Brain Research Bulletin. 1994;35(5-6):561–572. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(94)90170-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiech K, Kalisch R, Weiskopf N, Pleger B, Stephan KE, Dolan RJ. Anterolateral prefrontal cortex mediates the analgesic effect of expected and perceived control over pain. The Journal of Neuroscience : the Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2006;26(44):11501–11509. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2568-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams RH, Zimmerman DW. The comparative reliability of simple and residualized difference scores. Journal of Experimental Education. 1982;5151(2)(1982):94–97. [Google Scholar]