Abstract

Background

Rickettsia felis is a recently described flea-borne spotted fever group Rickettsia that is an emerging human pathogen. Although there is information on the organism from around the world, there is no information on the organism in China.

Methods

We used a commercial ELISA to detect antibodies reactive against R. felis in blood samples and developed a PCR to detect the gltA of the organism in blood samples and external parasites.

Results

We found reactive antibodies in people (16%; 28/180), dogs (47%; 128/271) and cats (21%; 19/90) and positive PCRs with DNA from people (0.1%; 1/822), dogs (0.8%; 8/1,059), mice (10%; 1/10), ticks (Rhipicephalus sanguineus; 10%; 15/146), lice (Linognathus setosus; 16%; 6/37), fleas (Ctenocephalides felis felis; 95%; 57/60) and mosquitoes (Anopheles sinensis, Culex pipiens pallens; 6%; 25/428), but not from cats (0/135) or canine fecal swabs (0/43).

Conclusions

This is the first report of R. felis in China where there is serological and/ or PCR evidence of the organism in previously reported [people, dogs, cats, ticks (Rhipicephalus sanguineus), fleas (Ctenocephalides felis felis) and mosquitoes (Anopheles sinensis, Culex pipiens pallens)] and novel species [mice and lice (Linognathus setosus)].

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12879-014-0682-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Rickettsia felis, China, Serology, PCR

Background

Although tick-borne spotted fever group rickettsiae have been described in China [1], there is no information on the flea-borne emerging human pathogen Rickettsia felis. Described in 2001, R. felis appears to have the cat flea, Ctenocephalides felis felis, as its main vector and reservoir and can infect other arthropods (mosquitoes, ticks and mites) and mammals (rats, opossums, dogs, and cats). It is found worldwide and, in Asia, it has been definitively identified by molecular methods in fleas (Indonesia, Thailand, Afghanistan, South Korea, Laos, Malaysia, Taiwan), ticks (Japan), raccoons (Japan) and people (Taiwan, South Korea) [2],[3]. To expand our knowledge on R. felis in Asia, we studied people, animals and arthropods from around China using serology and molecular techniques.

Methods

Samples collection

This study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Yangzhou University and the Institutional Review Board of Subei People’s Hospital, China. Written permission was obtained from participants and owners of animals that participated in the study. People sampled in Jiangsu province (Figure 1) were apparently healthy individuals attending the Subei People’s Hospital for routine health checks. Dogs sampled in Taixing of Jiangsu were apparently healthy animals in a breeding kennel while those from Gansu province were from a shelter. All other dog samples were obtained from patients with a variety of conditions attending local veterinary clinics. The cats sampled in Jiangsu were apparently healthy animals in a shelter while those from Beijing, Shanghai and Guangdong were from animals presenting to veterinary clinics with a variety of conditions. In Jiangsu, ticks and lice were obtained from breeding kennel dogs and fleas were obtained from feral cats. Mice and shrews were captured in traps in Guangdong and the mosquitoes were captured with hand-nets in the environs of the Yangzhou University of Jiangsu.

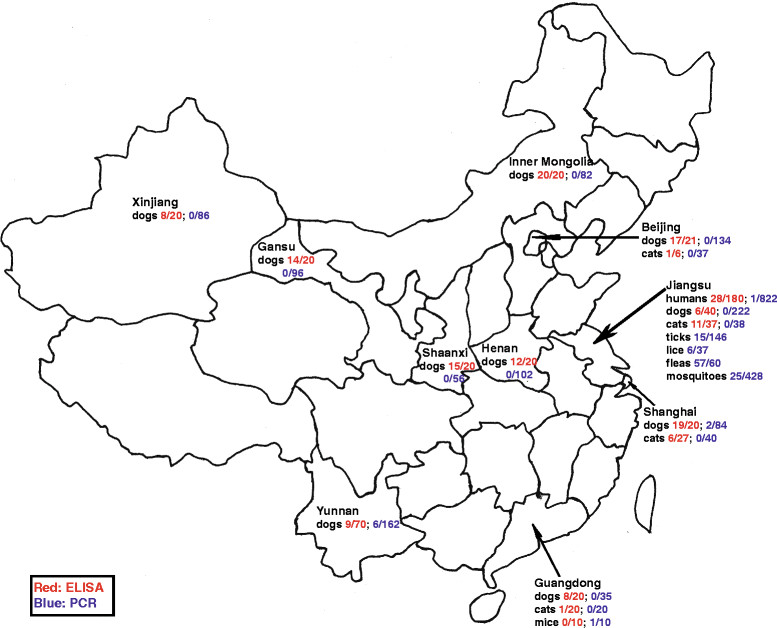

Figure 1.

Sites in China where samples were obtained for R. felis testing by ELISA and PCR. People sampled in Jiangsu province were apparently healthy individuals attending the Subei People’s Hospital for routine health checks. Dogs sampled in Taixing of Jiangsu were apparently healthy animals in a breeding kennel and parts of those from Gansu province were from a shelter while all other dog samples were obtained from patients with a variety of conditions attending the veterinary clinic. The cats sampled from Jiangsu were apparently healthy animals in a shelter while those from Beijing, Shanghai and Guangdong were from the veterinary clinic with variety conditions. In Jiangsu, ticks and lice were obtained from breeding kennel dogs and fleas were obtained from feral cats. The mice were captured in traps in Guangdong and the mosquitoes were captured with hand-nets in the environs of the Yangzhou University of Jiangsu.

Plasma and buffy coats from people, dogs, cats and wild mice (Figure 1) were stored at −80°C until DNA extraction. Rectal swabs from dogs and organs (spleen, liver and kidney) from the humanely euthanized wild mice were stored at −80°C in 800 μL of RNA/DNA Stabilization Reagent for Blood/Bone Marrow (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis) until DNA extraction. The external parasites collected from dogs and cats, and mosquitoes (Figure 1) were identified using standard morphological criteria and stored as above.

Serology assay

The R. felis EIA IgG Antibody Kit (Fuller Laboratory, USA) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions with peroxidase-conjugated AffiniPure Goat Anti-Cat, Rabbit Anti-Dog, and Goat Anti-Mouse IgG (H + L) (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, USA) substituted as secondary antibodies for cat, dog and mouse/shrew assays, respectively. For human plasma, the cut-off level was determined following the manufacturer’s instructions that an index (OD value of test serum divided by the average OD values of the Cutoff Calibrator) above 1.2 should be considered positive. Plasma from cats, mice, shrews and dogs was regarded as positive if they gave an OD value above the mean plus three standard deviations of the respective negative control samples [4],[5].

DNA extraction

Samples were thawed at room temperature and DNA was extracted from buffy coats, homogenized organs and arthropods [6], and canine rectal swabs with the QIAamp® DNA Blood Mini Kit (QIAgen, Valencia, USA), QIAamp® DNA Mini Kit, and QIAamp® DNA Stool Mini Kit, respectively, following the manufacturer’s protocol.

PCR assays

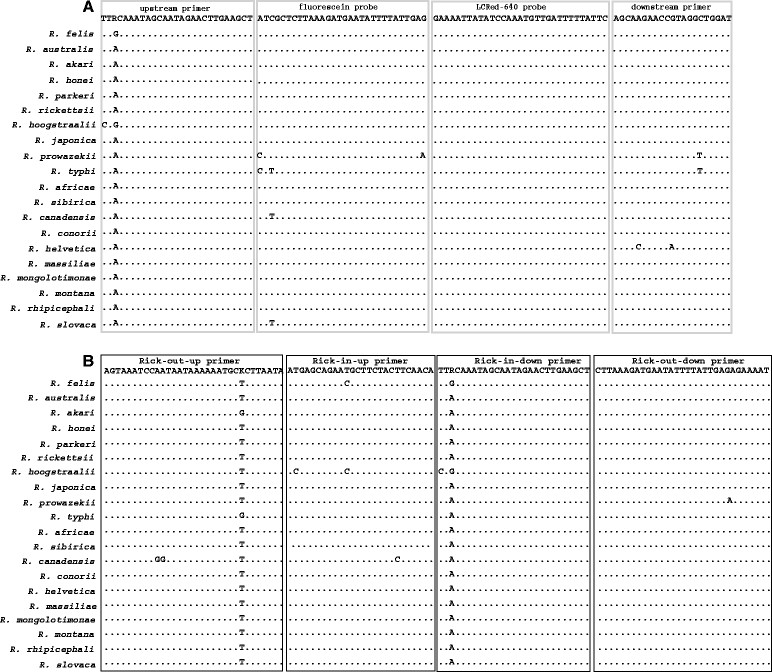

Using the Clustal Multiple Alignment Algorithm we identified a conserved region of the gltA in 20 representative Rickettsia species. Primers and probes were designed to amplify a 170-bp target using a FRET-PCR, and 446-bp and 353-bp targets using a nested-PCR (Figure 2). The PCRs were performed in a LightCycler® 480II PCR platform with hydroxymethylbilane synthase as an endogenous internal control [6]. Ten microliters of extracted DNA was tested in a 20 μL final volume of reaction mixture. Thermal cycling consisted of a denaturation step (2 min @ 95°C) and 18 high-stringency step-down cycles followed by 40 relaxed-stringency fluorescence acquisition cycles. The 18 high-stringency step-down thermal cycles were 6 × 1 sec @ 95°C, 12 sec @ 70°C, 8 sec @ 72°C; 9 × 1 sec @ 95°C, 12 sec @ 68°C, 8 sec @ 72°C; 3 × 1 sec @ 95°C, 12 sec @ 66°C, 8 sec @ 72°C. The relaxed-stringency fluorescence acquisition cycling consisted of 40 × 1 sec @ 95°C, followed by fluorescence acquisition of 8 sec @ 57°C, and 30 sec @ 72°C. Melting curve analysis for probes annealing to the PCR products was performed by monitoring the fluorescence from 38°C to 85°C with the first derivatives of F4/F1 being evaluated to determine the probe melting temperature (Tm). For nested-PCR, the PCR steps were the same as those in the FRET-PCR with the exclusion of the melting step. Positivity of samples was confirmed using gel electrophoresis with the SYBR® safe DNA Gel Stain (Invitrogen™, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and genomic sequencing conducted by a commercial company (GenScript, Nanjing, China). Two ultramer oligos (Integrated DNA Technologies, USA) containing portions of the gltA of R. felis and R. typhi were used to prepare quantitative standards (104 to 100gltA copies/10 μL) and establish the sensitivity. All the PCR assays were performed with plasmid standards and sterile H2O as positive and negative controls, respectively.

Figure 2.

Alignment of the primers and probes for the gltA -based FRET-qPCR and nested PCR with 20 Rickettsia species. Panel A shows the nucleotide sequences of the primers and probes used in the FRET-qPCR and the corresponding sequences of 20 Rickettsia species. Panel B shows the nucleotide sequences of the primers used for the nested PCR. In both Panels, dots indicate that nucleotides are identical to the primers. The nucleotides between oligonucleotides are not shown. The upstream primer and probes were used as shown while the downstream primer was used as an antisense oligonucleotide.

Results and discussion

The ELISAs showed high prevalences of antibodies to R. felis in people (16%; 28/180), dogs (47%; 128/271) and cats (21%; 19/90) (Figure 1, Table 1). Previous serosurveys have shown similar numbers of apparently healthy people in Colombia (18%), Spain (7%), Senegal (4%), and Kenya (3%) [7],[8] are seropositive. There were no differences in age or complete blood count (CBC) parameters between sero-positive and sero-negative people. People that were ELISA positive had an average age of 45.03 years ±14.57 and their complete blood count parameters were RBC: 4.76 × 1012/L ± 0.42, HCT: 43.52% ±3.57, WBC: 6.20 × 109/L ±1.73, NE%: 58.61 ± 8.35, and PLT: 211.00 × 109/L ±48.20. The average age of the sero-negative people was 45.15 years ±14.61 and their blood parameters were RBC: 4.76 × 1012/L ±0.42, HCT: 43.55% ±3.59, WBC: 6.20 × 109/L ±1.74, NE%: 58.54 ± 8.41, and PLT: 211.03 × 109/L ±47.66.

Table 1.

Details of samples collected in China and the results of ELISA and PCR testing

| Sample type | Source of samples | Sample number | Sero-positivity (%), pos/total samples | PCR-positivity (%), pos/total samples | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Province/ unicipality | City | Coordinates | ||||

| Human blood | Jiangsu | Yangzhou | 32°N, 119°E | 822 | 15.6%, 28/180 | 0.1%, 1/822 |

| Dog blood | Beijing | Beijing | 39°N, 116°E | 134 | 81.0%, 17/21 | 0.0%, 0/134 |

| Gansu | Lanzhou | 36°N, 103°E | 96 | 70.0%, 14/20 | 0.0%, 0/96 | |

| Guangdong | Guangzhou | 23°N, 113°E | 35 | 40.0%, 8/20 | 0.0%, 0/35 | |

| Henan | Zhengzhou | 34°N, 113°E | 102 | 60.0%, 12/20 | 0.0%, 0/102 | |

| Inner Mongolia | Huhhot | 40°N, 111°E | 82 | 100.0%, 20/20 | 0.0%, 0/82 | |

| Jiangsu | Yangzhou | 32°N, 119°E | 50 | 25.0%, 5/20 | 0.0%, 0/50 | |

| Taizhou | 32°N, 120°E | 111 | 0.0%, 0/10 | 0.0%, 0/111 | ||

| Nanjing | 32°N, 118°E | 61 | 10.0%, 1/10 | 0.0%, 0/61 | ||

| Shanghai | Shanghai | 31°N, 121°E | 84 | 95.0%, 19/20 | 2.4%, 2/84 | |

| Shaanxi | Yangling | 34°N, 108°E | 56 | 75.0%, 15/20 | 0.0%, 0/56 | |

| Xinjiang | Urumchi | 43°N, 87°E | 86 | 40.0%, 8/20 | 0.0%, 0/86 | |

| Yunnan | Kunming | 25°N, 102°E | 162 | 12.9%, 9/70 | 5.8%, 6/162 | |

| Cat blood | Beijing | Beijing | 39°N, 116°E | 37 | 16.7%, 1/6 | 0.0%, 0/37 |

| Guangdong | Guangzhou | 23°N, 113°E | 20 | 5.0%, 1/20 | 0.0%, 0/20 | |

| Jiangsu | Yangzhou | 32°N, 119°E | 38 | 29.7%, 11/37 | 0.0%, 0/38 | |

| Shanghai | Shanghai | 31°N, 121°E | 50 | 22.2%, 6/27 | 0.0%, 0/50 | |

| Lice | Jiangsu | Taizhou | 32°N, 120°E | 37 | NA* | 16.2%, 6/37 |

| Tick | Jiangsu | Taizhou | 32°N, 120°E | 146 | NA | 10.3%, 15/146 |

| Cat flea | Jiangsu | Yangzhou | 32°N, 119°E | 60 | NA | 95.0%, 57/60 |

| Mosquito | Jiangsu | Yangzhou | 32°N, 119°E | 664 | NA | 6.3%, 42/664 |

| Dog Rectal swab | Yunnan | Kunming | 25°N, 102°E | 43 | NA | 0.0%, 0/43 |

| Mouse blood | Guangdong | Zhanjiang | 21°N, 110°E | 10 | NA | 0.0%, 0/10 |

| Liver | 10 | NA | 0.0%, 0/10 | |||

| Kidney | 10 | NA | 0.0%, 0/10 | |||

| Spleen | 10 | NA | 10.0%, 1/10 | |||

Seropositive dogs were found in each area studied with prevalences from 13-100%, similar to the 51% reported in Spain and Australia, and ≤13% in Brazil [9],[10]. There were significantly fewer seropositive cats (5-30%; two-tailed chi square analysis, P < 10−4), similar to the low level reported in the US (< 11%) [11]. All mice (6 Mus musculus) and shrews (4 Suncus murinus) that were trapped were seronegative.

Although it has been suggested there might be high specificity of R. felis in serological tests [9] there is at least some serological cross reactivity between R. felis and other Rickettsia spp. present in China [1]. We therefore used PCR to definitively identify R. felis in our study populations and provide further prevalence data. The GenBank BLAST program showed primers and probes of our FRET-PCR and nested PCR recognized all Rickettsia spp., but none in the other genera of the Rickettsiaceae. The detection limit of our combination PCR system was one gene copy per 20 μl reaction system.

Our PCRs showed one person had DNA of R. felis (0.1%; 1/822), a twenty-seven year old man with a normal CBC who was seronegative. This might have been an acute infection or an asymptomatic infection with no serological response as reported previously [8]. Dogs from 2 of the 10 areas studied were also PCR positive (0.8%; 8/1,059), similar to Australia where up to 9% of dogs are PCR positive [9]. Previously, R. felis was found in feces from great apes in Africa [12] but all our canine rectal swabs were negative by PCR. These dogs, however, had negative serology and blood PCRs and were probably then not infected.

As found previously [13], all the cats we studied were negative by PCR, despite many being seropositive and many harboring PCR positive Ctenocephalides felis, cat fleas. Fleas were the only ectoparasites found on cats and almost all were PCR positive (95%; 57/60), consistent with the very high levels of infection found worldwide and the generally accepted hypothesis that cat fleas are the primary arthropod vectors and reservoirs [3]. Our finding that dogs have a higher seroprevalence and are positive by PCRs supports the hypothesis that they, rather than cats, might be the main mammalian reservoir of R. felis [14].

The spleen of one M. musculus was PCR positive for R. felis which is the first definitive report of the organism in mice. A PCR positive Rattus norvegicus has also been reported [15] and investigation into the role of rodents in the epidemiology of R. felis appears warranted.

All the amplicons we obtained in the above PCRs had identical sequences to those of the R. felis type strain URRWXCal2 (CP000053). In addition the amplicons had identical sequences with other strains of R. felis including those with GenBank sequences JQ674484 (from Aedes albopictus mosquitoes, Libreville, Gabon) and JN375498 (from Canis familiaris in Southeastern Brazil). We submitted sequences obtained from two dogs to GenBank along with some of the sequences described below (Table 2).

Table 2.

Details of the sequences we obtained in our study and submitted to GenBank

| GenBank No. | Submission No. | Species |

|---|---|---|

| KJ440515 | 1698905 | Dog - Canis lupus familiaris |

| KJ440516 | 1698976 | Dog - Canis lupus familiaris |

| KJ440517 | 1698981 | Louse - Linognathus setosus |

| KJ440518 | 1698985 | Louse - Linognathus setosus |

| KJ440519 | 1698989 | Mosquito - Anopheles sinensis |

| KJ440520 | 1699024 | Mosquito - Culex pipiens pallens |

| KJ440521 | 1699027 | Tick - Rhipicephalus sanguineus |

| KJ440522 | 1699029 | Louse - Linognathus setosus |

| KJ440523 | 1699030 | Mosquito - Anopheles sinensis |

Ten percent of the ticks (146 Rhipicephalus sanguineus) we collected from dogs were PCR positive. The sequences were all identical to R. felis (CP000053) except one (KJ440521) which was 99% identical to R. felis (CP000053) and R. typhi (U59714). Sixteen percent (6/37) of the dog lice (all Linognathus setosus) were positive; four had amplicons identical to R. felis (CP000053) while two amplicons from dog lice (KJ440522) were similar to R. endosymbiont (EU760765) (97%), R. bellii (U59716) (96%) and R. felis (CP000053) (86%). While R. felis has been reported in R. sanguineus in South America [16], ours is the first report of the organism in lice. All the dogs with PCR positive lice or ticks were sero- and PCR negative for R. felis suggesting these arthropods might not be competent vectors.

Six percent (25/428) of the mosquitoes (32 Anopheles sinensis, 396 Culex pipiens pallens) were PCR positive with 23 (2 An. sinensis, 21 C. p. pallens) having sequences identical to R. felis (CP000053) and 2 (C. p. pallens) having 99% and 96% similarity. The latter was 99% identical to a novel Rickettsia sp. (JN620082) found in An. gambiae in Africa which may be a new human pathogen [17]. Ours is the first report of R. felis and the new Rickettsia sp. in mosquitoes outside of Africa and the first of the organisms in An. sinensis and C. p. pallens. Further studies are indicated to determine the role of mosquitoes in the epidemiology of these rickettsias and the influence of the Rickettsia spp. might have on the biology of mosquitoes.

Conclusions

Our study indicates that R. felis occurs widely in China and infects a variety of previously reported (people, dogs, cats, ticks, fleas and mosquitoes) and novel species (mice and lice). Further studies are indicated to investigate the epidemiology and transmission mechanisms of R. felis, particularly in mosquitoes, lice and mice.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NO: 31472225) and the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions, Yangzhou, Jiangsu, P. R. China.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

CW, JZ, and PK designed the experiment. JZ, GL, ZZ, DY, LW and SGL performed the experiment. CW and PK wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of manuscript.

Contributor Information

Jilei Zhang, Email: zhangjilei0103@163.com.

Guangwu Lu, Email: guangwulu@163.com.

Patrick Kelly, Email: pkelly@rossvet.edu.kn.

Zhenwen Zhang, Email: yzdxzzw@163.com.

Lanjing Wei, Email: weilanjing4123@163.com.

Duonan Yu, Email: duonan@yahoo.com.

Shayilan Kayizha, Email: 511366016@qq.com.

Chengming Wang, Email: wangcm@yzu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Lu L, Chesters D, Zhang W, Li G, Ma Y, Ma H, Song X, Wu H, Meng F, Zhu C, Liu Q. Small mammal investigation in spotted fever focus with DNA-barcoding and taxonomic implications on rodents species from Hainan of China. PLoS One. 2012;7:e43479. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parola P. Rickettsia felis: from a rare disease in the USA to a common cause of fever in sub-Saharan Africa. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17:996–1000. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sashika M, Abe G, Matsumoto K, Inokuma H. Molecular survey of rickettsial agents in feral raccoons (Procyon lotor) in Hokkaido, Japan. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2010;63:353–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lewis SM, Osei-Bimpong A. Haemoglobinometry in general practice. Clin Lab Haematol. 2003;25:343–346. doi: 10.1046/j.0141-9854.2003.00553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sun A, Wang Y, Du P, Wu S, Yan J. A sensitive and specific IgM-ELISA for the serological diagnosis of human leptospirosis using a rLipL32/1-LipL21-OmpL1/2 fusion protein. Biomed Environ Sci. 2011;24:291–299. doi: 10.3967/0895-3988.2011.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wei L, Kelly P, Zhang J, Yang Y, Zheng X, Tao J, Zhang Z, Wang C: Use of a universal hydroxymethylbilane synthase (HMBS)-based PCR as an endogenous internal control and to enable typing of mammalian DNAs. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2014, Mar 20 (Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Hidalgo M, Montoya V, Martínez A, Mercado M, De la Ossa A, Vélez C, Estrada G, Perez JE, Faccini-Martinez AA, Labruna MB, Valbuena G. Flea-borne rickettsioses in the north of Caldas province, Colombia. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2013;13:289–294. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2012.1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mediannikov O, Socolovschi C, Edouard S, Fenollar F, Mouffok N, Bassene H, Diatta G, Tall A, Niangaly H, Doumbo O, Lekana-Douki JB, Znazen A, Sarih M, Ratmanov P, Richet H, Ndiath MO, Sokhna C, Parola P, Raoult D. Common epidemiology of Rickettsia felisinfection and Malaria, Africa. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:1775–1783. doi: 10.3201/eid1911.130361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hii SF, Kopp SR, Thompson MF, O’Leary CA, Rees RL, Traub RJ. Molecular evidence of Rickettsia felisinfection in dogs from northern territory. Australia Parasit Vectors. 2011;4:198. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-4-198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Melo AL, Martins TF, Horta MC, Moraes-Filho J, Pacheco RC, Labruna MB, Aguiar DM. Seroprevalence and risk factors to Ehrlichia spp. and Rickettsiaspp. in dogs from the Pantanal Region of Mato Grosso State, Brazil. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2011;2:213–218. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bayliss DB, Morris AK, Horta MC, Labruna MB, Radecki SV, Hawley JR, Brewer MM, Lappin MR. Prevalence of Rickettsia species antibodies and Rickettsiaspecies DNA in the blood of cats with and without fever. J Feline Med Surg. 2009;11:266–270. doi: 10.1016/j.jfms.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keita AK, Socolovschi C, Ahuka-Mundeke S, Ratmanov P, Butel C, Ayouba A, Inogwabini BI, Muyembe-Tamfum JJ, Mpoudi-Ngole E, Delaporte E, Peeters M, Fenollar F, Raoult D. Molecular evidence for the presence of Rickettsia felisin the feces of wild-living African apes. PLoS One. 2013;8:e54679. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Assarasakorn S, Veir JK, Hawley JR, Brewer MM, Morris AK, Hill AE, Lappin MR. Prevalence of Bartonella species, hemoplasmas, and Rickettsia felisDNA in blood and fleas of cats in Bangkok, Thailand. Res Vet Sci. 2012;93:1213–1216. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2012.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hii SF, Kopp SR, Abdad MY, Thompson MF, O’Leary CA, Rees RL, Traub RJ. Molecular evidence supports the role of dogs as potential reservoirs for Rickettsia felis. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2011;11:1007–1012. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2010.0270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abramowicz KF, Rood MP, Krueger L, Eremeeva ME. Urban focus of Rickettsia typhi and Rickettsia felisin Los Angeles, California. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2011;11:979–984. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2010.0117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abarca K, López J, Acosta-Jamett G, Martínez-Valdebenito C. Rickettsia felis in Rhipicephalus sanguineusfrom Two Distant Chilean Cities. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Diseases. 2013;8:607–609. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2012.1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Socolovschi C, Pages F, Ndiath MO, Ratmanov P, Raoult D. Rickettsiaspecies in African Anopheles mosquitoes. PLoS One. 2012;7:e48254. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]