Abstract

Background

Transcutaneous nerve stimulation (TENS) has been proposed as a means of reducing pain in labour. The TENS unit emits low-voltage electrical impulses which vary in frequency and intensity. During labour, TENS electrodes are generally placed on the lower back, although TENS may be used to stimulate acupuncture points or other parts of the body. The physiological mechanisms whereby TENS relieves pain are uncertain. TENS machines are frequently operated by women, which may increase a sense of control in labour.

Objectives

To assess the effects of TENS on pain in labour.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register (30 April 2011) and reference lists of retrieved papers.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials comparing women receiving TENS for pain management in labour versus routine care, alternative non-pharmacological methods of pain relief, or placebo devices. We included all types of TENS machines.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors assessed for inclusion all trials identified by the search strategy, carried out data extraction and assessed risk of bias. We have recorded reasons for excluding studies.

Main results

Seventeen trials with 1466 women contribute data to the review. Thirteen examined TENS applied to the back, two to acupuncture points, and two to the cranium. Overall, there was little difference in pain ratings between TENS and control groups, although women receiving TENS to acupuncture points were less likely to report severe pain (average risk ratio 0.41, 95% confidence interval 0.31 to 0.54; measured in two studies). The majority of women using TENS said they would be willing to use it again in a future labour. Where TENS was used as an adjunct to epidural analgesia there was no evidence that it reduced pain. There was no consistent evidence that TENS had any impact on interventions and outcomes in labour. There was little information on outcomes for mothers and babies. No adverse events were reported.

Authors’ conclusions

There is only limited evidence that TENS reduces pain in labour and it does not seem to have any impact (either positive or negative) on other outcomes for mothers or babies. The use of TENS at home in early labour has not been evaluated. TENS is widely available in hospital settings and women should have the choice of using it in labour.

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH): *Labor, Obstetric; Labor Pain [*therapy]; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Transcutaneous Electric Nerve Stimulation [*methods]

MeSH check words: Female, Humans, Pregnancy

BACKGROUND

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) is a non-pharmacological method for relieving pain. It has been used to relieve both acute and chronic pain in a variety of settings, and for a range of conditions including dysmenorrhoea (period pain) and back pain (Kaplan 1998; Samanta 1999). TENS has been used in childbirth since the 1970s (Augustinsson 1977).

This review is one in a series of Cochrane reviews examining pain management in labour. These reviews contribute to an overview of systematic reviews of pain management for women in labour (Jones 2011b) and share a generic protocol (Jones 2011a).

Description of the intervention

Pain in labour is a complex phenomenon, and it is known that women’s experiences of pain and labour vary enormously (Lowe 2002; Simkin 1989). Physiological, cognitive and psychological factors all seem to be involved in determining individual experience. The precise mechanisms whereby TENS relieves pain are not known. A number of theories have been proposed.

First is the ‘gate control theory’ of pain (Melzack 1965). According to this theory, the transmission of pain is inhibited by the stimulation of large, afferent nerve fibres which carry impulses towards the central nervous system. When afferent nerves are stimulated, the pathway for other (painful) stimuli is closed by the operation of a ‘gate’ in the spinal cord that controls transmissions to the brain. When applied to the lower back, the TENS unit emits electrical impulses which excite afferent nerves, and thus inhibits the transmission of painful stimuli arising from the uterus, vagina and perineum during labour (Augustinsson 1977). (According to this theory, the application of heat, cold or massage would be likely to have a similar effect.)

Second, it is suggested that painful stimuli result in chemical changes in the brain, most notably, the release of endorphins which mediate the experience of pain. TENS is thought to complement this chemical process (Lechner 1991). Again, the precise mechanisms are not understood. However, by reducing anxiety, increasing a sense of control, and by providing distraction, TENS is thought to increase women’s sense of well-being and thereby reduce pain in labour (Brucker 1984; Findley 1999; Gentz 2001; Simkin 2004). It has also been proposed that by decreasing maternal anxiety, TENS may reduce the length of labour by suppressing the release of catecholamines which can inhibit the action of the uterus and thereby delay progress (Lowe 2002).

More recent theories suggest that the varied factors influencing the experience of pain are likely to be interactive (Holdcroft 2003; Lowe 2002).

Various models of TENS equipment are available (Kaplan 1997). The TENS unit consists of a hand-held device connected to electrodes which are attached to the skin. During labour the electrodes are usually positioned on the lower back on both sides of the spine at vertebral positions T10 and S2 (Kaplan 1998; Simkin 2004), corresponding to the nerve pathways through which painful impulses from the contracting uterus are thought to enter the spinal cord (Lowe 2002). The TENS unit emits low-voltage impulses, the frequency and intensity of which can be controlled by the woman in labour. When using TENS, women experience a tingling or buzzing feeling at the site of the electrodes. At low voltages these sensations are not painful. TENS has also been used to stimulate acupuncture points, and can also be applied to the cranium by trained therapists.

The availability of TENS has increased over the past two decades. The extent of its use by women in different countries and settings, and at different stages in labour, has not been well documented. A UK study suggested that in 1994 approximately 16% of low-risk primiparous women used TENS in labour; invariably TENS was used alongside other methods of pain relief (Williams 1998). This figure is higher than has been reported in other studies (Carroll 1997; Rajan 1994). A more recent study of maternity units in the UK suggests that the use of TENS was supported by midwives in all units surveyed, although only approximately a fifth had TENS available. The use of TENS by women admitted to these units was reported to be between 1% and 25% although this information was not always routinely recorded; the extent of its use by women at home in early labour remains uncertain (McMunn 2009).

The use of TENS to relieve pain in labour remains controversial. While there is evidence that the technology is well received by women, it is not clear that this is because it is effective in reducing pain. There is evidence that women’s satisfaction with the experience of childbirth is affected by their sense of control during labour, and in particular, their sense of control during painful contractions (Green 2003). The fact that women themselves operate the TENS unit may partly explain its popularity. In addition, the units may be used in a variety of settings, and it has been suggested that using the device at home in early labour may delay admission to hospital.

The intervention does not seem to have serious adverse effects on women or their babies, although there has been only limited research in this area (Simkin 1989; Simkin 2004). Serious side effects are rare, but the electrodes may cause some local skin irritation. The use of TENS has cost implications, not only in terms of the purchase or hire of the TENS units but also in terms of staff time setting up the equipment and demonstrating its use to women. There is some, limited, evidence that TENS can interfere with the operation of other electrical equipment (Bundsen 1981).

Why it is important to do this review

TENS aims to reduce pain in labour. TENS can be used alone or in combination with other non-pharmacological and pharmacological methods of pain relief (Kaplan 1998). Proponents of the therapy argue that it reduces maternal distress and potentially reduces the duration of labour and the need for more invasive co-intervention. On the other hand, if TENS is not effective, it may increase maternal distress by delaying the use of more effective interventions (Gentz 2001).

The review assesses the available evidence from randomised trials examining the effects of TENS in labour on outcomes for women and babies.

OBJECTIVES

To assess the effect of TENS on pain in labour.

METHODS

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs). We have not included quasi-randomised trials.

Types of participants

Women in labour.

Types of interventions

There are various models and types of TENS equipment available; we have not restricted the inclusion criteria to any particular device specification. We have included studies where women were randomised to receive TENS versus routine care, a placebo TENS device, or non-pharmacological interventions. We are aware that the use of sham TENS devices may not be an adequate means of blinding women to group allocation, and the use of such devices may influence caregiver behaviour. We have taken this into account in the interpretation of results.

This review is one in a series of Cochrane reviews examining pain management in labour. These reviews contribute to an overview of systematic reviews of interventions for pain management in labour (Jones 2011b), and share a generic protocol (Jones 2011a). To avoid duplication, the different methods of pain management have been listed in a specific order, from one to 15. Individual reviews focusing on particular interventions include comparisons with only the interventions above it on the list. Methods of pain management identified in the future will be added to the end of the list. The current list is as follows.

Placebo/no treatment

Hypnosis

Biofeedback (Barragán 2011)

Intracutaneous or subcutaneous sterile water injection (Derry 2011)

Immersion in water (Cluett 2009)

Aromatherapy (Smith 2011b)

Relaxation techniques (yoga, music, audio)

Acupuncture or acupressure (Smith 2011a)

Manual methods (massage, reflexology)

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) (this review)

Inhaled analgesia

Opioids (Ullman 2010)

Non-opioid drugs (Othman 2011)

Local anaesthetic nerve blocks

Epidural (including combined spinal epidural) (Anim-Somuah 2005; Simmons 2007)

Accordingly, where data are available, this review will only include comparisons of TENS with: 1. Placebo/no treatment; 2. Hypnosis; 3. Biofeedback; 4. Intracutaneous or subcutaneous sterile water injection; 5. Immersion in water; 6. Aromatherapy; 7. Relaxation techniques; 8. Acupuncture or acupressure; or 9. Manual methods.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Pain intensity in labour (measured as a continuous variable using visual analogue scales or by validated questionnaires or as a dichotomous variable has/has not severe pain)

Satisfaction with pain relief during labour (as defined by trialists)

Secondary outcomes

Maternal

Duration of labour

Sense of control in labour (as defined by trialists)

Augmentation of labour

Induction of labour

Use of other methods of pain relief during labour

Assisted vaginal birth (instrumental vaginal delivery; forceps or vacuum extraction)

Caesarean section

Side effects (e.g. local skin irritation)

Satisfaction with childbirth experience (as defined by trialists)

Cervical dilatation on admission to hospital

Breastfeeding

Effect (negative) on mother/baby interaction

Fetal/neonate

Apgar score less than seven at five minutes

Cord blood pH less than 7.1

Adverse events (as defined by trialists)

Admission to neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) or special care baby unit (SCBU)

Infant outcomes at long term follow-up (as defined by trialists)

Other outcomes

Cost (as defined by trialists)

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register by contacting the Trials Search Co-ordinator (30 April 2011).

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co-ordinator and contains trials identified from:

quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE;

weekly searches of EMBASE;

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE and EMBASE, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co-ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of relevant papers.

We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (TD and CB) independently examined abstracts of all potential studies identified by the search to ascertain which met the inclusion criteria. Where we did not have enough information to determine eligibility we sought further information from the study authors. We resolved any disagreement through discussion between all review authors.

The reasons for excluding studies have been set out in the Characteristics of excluded studies tables.

Data extraction and management

All review authors were involved in designing, piloting and revising the data extraction form. Two review authors (TD, CB) independently extracted data using the agreed form. We resolved any disagreement through discussion. After checking (by TD), we entered data into Review Manager (RevMan) software (RevMan 2011) and CB then re-checked the data.

When information regarding study methods and findings were unclear, we attempted to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Assessment of methodological quality of included studies

Two review authors (TD, CB) independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We resolved any disagreement by discussion or by involving a third assessor.

(1) Sequence generation

We have described the methods used for generation of the randomisation sequence for each trial and assessed them as low risk of bias (any truly random process), unclear, or high risk of bias. We assessed the method as:

low risk of bias (e.g. random number table; computer random number generator),

high risk of bias (any non-random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number) or,

unclear.

(2) Allocation concealment

We assessed the quality of each trial, using the following criteria:

low risk of bias for concealment of allocation: such as telephone randomisation, consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes;

unclear risk of bias for concealment of allocation: e.g. the study does not report any concealment approach;

high risk of bias for allocation concealment: such as open list of random number tables, use of case record numbers, dates of birth or days of the week.

(3) Attrition (loss of participants, e.g. withdrawals, dropouts, protocol deviations)

We described for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported, the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. We assessed methods as:

low risk of bias (low levels of sample attrition, reasons for loss explained and balanced across groups);

high risk of bias (levels of attrition above 20% or loss not balanced across groups);

unclear.

(4) Blinding of participants, researchers and outcome assessors (checking for performance and detection bias)

We assessed blinding using the following criteria:

low, high or unclear risk of bias for participants;

low, high or unclear risk of bias for personnel;

low, high or unclear risk of bias for outcome assessors

We are aware that blinding women and caregivers where TENS has been compared with sham TENS may not be convincing, but we have recorded where an attempt at blinding has been made.

(5) Selective reporting bias

We described for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found. We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (where it is clear that all of the study’s pre-specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

high risk of bias (where not all the study’s pre-specified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre-specified; outcomes of interest are reported incompletely and so cannot be used; study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear.

(6) Other sources of bias

We described for each included study any concerns we had about other possible sources of bias.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about whether studies were at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Handbook (Higgins 2011). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we assessed the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered it likely to impact on the findings.

Measures of treatment effect

We carried out statistical analysis using RevMan software (RevMan 2011). We had anticipated that studies evaluating TENS were likely to include a range of comparison groups and that data on different outcomes (measured in different ways and at different time points) would have been recorded. Where trials were not sufficiently similar, we analysed and presented results separately. However, where possible, and at least for the primary outcome (pain in labour) we have used meta-analysis for combining data to produce a summary statistic.

Dichotomous data

Where, for example, outcome data such as maternal perceptions of pain have been measured as a dichotomous variable (e.g. severe pain versus no severe pain), we have presented results as summary risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Continuous data

For continuous data (e.g. pain measured on visual analogue scales), we have used the mean difference (MD) where outcomes have been measured in the same way between trials. We have used the standardised mean difference (SMD) to combine trials that measure the same outcome, but used different methods.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster-randomised trials

We had intended to include cluster-randomised trials in the analyses along with individually randomised trials. Their sample sizes would have been adjusted using the methods described in Gates 2005 and Higgins 2008 using an estimate of the intracluster correlation co-efficient (ICC) derived from the trial (if possible), or from another source.

If we had used ICCs from other sources, we would have reported this and conducted sensitivity analyses to investigate the effect of variation in the ICC. If we had identified both cluster-randomised trials and individually-randomised trials, we planned to synthesise the relevant information. We would have considered it reasonable to combine the results from both if there was little heterogeneity between the study designs and the interaction between the effect of intervention and the choice of randomisation unit was considered to be unlikely.

We would also have acknowledged heterogeneity in the randomisation unit and performed a subgroup analysis to investigate the effects of the randomisation unit.

We did not identify any cluster-randomised trials for this review, but will include them in updates if such trials are identified in the future.

Cross-over trials

We did not anticipate that there would be any cross-over trials for an intervention carried out during labour, however, one such trial was identified (Chia 1990) but we excluded it for other reasons. In updates of the review, if further cross-over trials are identified which are otherwise eligible for inclusion, we will only include data from the first stage of such studies to avoid the risk of bias associated with treatment order effect.

Dealing with missing data

We have analysed data on all participants with available data in the group to which they were allocated, regardless of whether or not they received the allocated intervention, and irrespective of whether they used additional interventions. If, in the original reports, participants were not analysed in the group to which they were randomised, and there was sufficient information in the trial report, we have attempted to restore them to the correct group. We noted levels of attrition in included studies.

Where data were not reported for some outcomes or groups, we attempted to contact the study authors to obtain the missing data.

Assessment of heterogeneity

As part of the meta-analyses we examined heterogeneity between trials using the I2 statistic. We regarded heterogeneity as substantial if I2 was greater than 30%. Where we identified unexplained heterogeneity among the trials we have made this explicit, so that this can be taken into account in the interpretation of results.

Assessment of reporting biases

If 10 or more studies had contributed data to meta-analysis for any particular outcome, we planned to investigate reporting biases (such as publication bias) using funnel plots. We would have assessed possible asymmetry visually, and used formal tests for funnel plot asymmetry. For continuous outcomes, we would have used the test proposed by Egger 1997, and for dichotomous outcomes, we would have used the test proposed by Harbord 2006. If asymmetry was detected in any of these tests or was suggested by a visual assessment, we planned to perform exploratory analyses to investigate it. In this version of the review insufficient data were available to allow us to carry out this planned analysis.

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using the RevMan software (RevMan 2011). We used fixed-effect meta-analysis for combining data where it was reasonable to assume that studies were estimating the same underlying treatment effect: i.e. where trials examined the same intervention, and where we judged the trials’ populations and methods to be sufficiently similar. If we suspected clinical heterogeneity sufficient to expect the underlying treatment effects to differ between trials, or if substantial statistical heterogeneity was detected, we used random-effects meta-analysis to produce an overall summary provided that we considered an average treatment effect across trials was clinically meaningful.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned subgroup analyses classifying whole trials by interaction tests as described by Deeks 2001.

For the primary outcomes, where data were available, we planned the following subgroup analyses.

Parity (nulliparous versus multiparous women)

Stage of labour (first stage latent versus active phase)

Spontaneous labour versus induced labour

Term versus preterm birth

Continuous support in labour versus no continuous support

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to carry out sensitivity analyses to explore the effect of trial quality assessed by concealment of allocation, high attrition rates, or both, with poor quality studies being excluded from the analyses in order to assess whether this made any difference to the overall result.

RESULTS

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of studies awaiting classification.

Results of the search

We identified a total of 28 studies from the search strategy. This review includes 18 studies, with data from 17 studies. One study which was otherwise eligible for inclusion was reported in a brief abstract and did not report any outcome data by randomisation group (Vasegh 2010); we have provided information about this trial in a Characteristics of included studies table but this study does not contribute any outcome data, and is not otherwise discussed in the remaining sections of the review. We excluded nine studies and one study was reported in Portuguese and is awaiting translation and eligibility assessment (Knobel 2005).

Included studies

We have included data from 17 studies with data for a total of 1466 women. Thirteen studies examined TENS applied to the lower back, two the application of TENS to acupuncture points to relieve pain in labour and two the application of Limoge currents to the cranium.

The studies were carried out in a variety of settings and countries. Of the studies examining TENS applied to the back, three were carried out in the USA (Hughes 1988; Tsen 2000; Tsen 2001) and one each in Sweden (Bundsen 1982), Brazil (de Orange 2003), Ireland (Hughes 1988), Canada (Labrecque 1999), Australia (Thomas 1988), Denmark (Steptoe 1984), India (Thakur 2004), Germany (Neumark 1978), Norway (Nesheim 1981), and the Netherlands (van der Ploeg 1996). Two studies focusing on TENS applied to acupuncture points were carried out in Taiwan (Chao 2007) and China (Wang 2007). Both studies examining TENS (Limoge current) to the cranium were carried out in France (Champagne 1984; Wattrisse 1993).

In ten studies TENS was compared with the use of a placebo machine (Champagne 1984; Chao 2007; Harrison 1986; Hughes 1988; Nesheim 1981; Steptoe 1984; Thomas 1988; Tsen 2000; Tsen 2001; van der Ploeg 1996). In the remaining studies, the use of TENS was compared with no intervention (routine care) (Bundsen 1982; de Orange 2003; Labrecque 1999; Neumark 1978; Thakur 2004; Wang 2007; Wattrisse 1993). Three of these studies included three arms: the study by Thakur 2004 compared TENS versus usual care or versus tramadol; a small study by Neumark 1978 examined TENS versus control groups or versus pethidine; and the study by Labrecque 1999 compared TENS versus usual care or versus sterile water injection. For two of these studies we have only included data for those arms comparing TENS with no treatment/placebo (Thakur 2004; Neumark 1978). The data comparing TENs with opioids has been included in another pain management review (Ullman 2010). In the study by Labrecque 1999 we have included the data for TENs versus control and TENS versus sterile water injection in two separate comparisons. The co-interventions in the various studies varied, and are described more fully in the Characteristics of included studies tables. In two studies by the same author (Tsen 2000; Tsen 2001), women used TENS to the back at the same time as epidural or combined spinal epidural analgesia, and in the trial by Wattrisse 1993, TENS to the cranium was also examined as an adjuvant therapy to epidural analgesia. In the study by de Orange 2003, women used TENS for a short period prior to the insertion of a spinal epidural. In most of the remaining trials, women in both study groups were free to use other analgesia on request. However, in the studies by Neumark 1978 and Wang 2007, women received no analgesics other than the study interventions. In addition, there was considerable variation amongst the studies in terms of the care women received, and in inclusion and exclusion criteria. In some trials women undergoing induction of labour were excluded, whereas in others, such women were included as part of the sample, and the use of oxytocin was routine in some settings. In some cases women were excluded if they had any analgesia before entry to the trial, whereas for example, in the study by van der Ploeg 1996 all women, in both the intervention and control arms, received patient-controlled pethidine (75 mg) and promethazine (25 mg). These variations in the care received by women in different studies mean that the interpretation of results from the review is not simple.

Information on the characteristics of women included in studies and descriptions of inclusion and exclusion criteria were sometimes limited. It appeared that four studies included only women in spontaneous labour (Harrison 1986; Thakur 2004; Tsen 2000; Tsen 2001), one study included only women with induced labours (Bundsen 1982), one study included a mix of women in both spontaneous and induced labours, while inclusion criteria relating to labour onset were not specified in the remaining studies. Few of the studies provided a breakdown of findings by parity. Four of the studies included primiparous women only (Champagne 1984; Steptoe 1984; Wang 2007; Wattrisse 1993); the rest included both primiparous and multiparous women. Ten studies included only women at term (Chao 2007; de Orange 2003; Hughes 1988; Labrecque 1999; Nesheim 1981; Thakur 2004; Thomas 1988; Tsen 2000; Tsen 2001; Wattrisse 1993) and in the remaining studies gestational age was not specified. No study reported on whether or not women had continuous support during labour.

Excluded studies

We excluded nine studies from the review. In two cases this was because they did not focus on the use of TENS during labour to relieve pain. Canino 1987 examined the use of TENS for pain relief following caesarean section and Dunn 1989 looked at the effects of TENS on the strength of uterine contractions during labour induction. We excluded the studies by Erkkola 1980, Hulkko 1979, Merry 1983 and Tajali-Awal 1995 for methodological reasons; in the former three studies, group allocation was not random, and in the latter post-randomisation attrition was very high. One study was reported in a brief conference abstract; we made several attempts to contact the study author without success (Anonymous 1995). Finally, two studies which were included in earlier versions of this review (Chia 1990; Tawfik 1982) have been excluded from this update. The reason for these additional exclusions is because this review is one in a series of Cochrane reviews which contribute to an overview of systematic reviews of pain relief for women in labour (Jones 2011b) and share a generic protocol (Jones 2011a). In order to comply with the generic protocol, which has specific inclusion criteria relating to comparison interventions so as to avoid overlap between different reviews, the Tawfik 1982 trial (TENS versus pethidine) has been moved to the parenteral opioids review (Ullman 2010), and the Chia 1990 trial (TENS versus Entonox®) to the inhaled analgesia review (Klomp 2011 in preparation) as neither trial now meets the inclusion criteria for this updated TENS review.

Risk of bias in included studies

Overall, there was little information on methods provided by study authors.

Allocation

Most of the included studies provided very little information on sequence generation or on allocation concealment. In three studies, sequence generation was by computer or by using random number tables (de Orange 2003; Labrecque 1999; Thomas 1988); for the rest, the method of generating the allocation sequence was not clear. In one study exactly the same numbers of primiparous and multiparous women were included in both arms of the trial, as stratification was not mentioned, this balance between groups seems unlikely to have occurred as a result of any truly random method of sequence generation (Thakur 2004).

Little information was provided on steps taken by the investigators to conceal group allocation. One study described using “sealed envelopes” (de Orange 2003); another three, sealed, opaque, sequentially numbered envelopes (Labrecque 1999; Tsen 2000; Tsen 2001). All but one of the remaining studies either did not describe methods to conceal allocation or the method was not clear. In one study allocation was by tossing a coin after recruitment; although it was not clear who was involved in recruiting women to the study; this method is likely to introduce a high risk of bias (Nesheim 1981).

Blinding

As we have described above, in several studies investigators attempted to blind study participants and care providers to group allocation by providing a placebo device (Champagne 1984; Chao 2007; Harrison 1986; Hughes 1988; Nesheim 1981; Neumark 1978; Steptoe 1984; Thomas 1988; Tsen 2000; Tsen 2001; van der Ploeg 1996). Assessing the success of blinding and risk of bias where sham TENS devices were provided was extremely difficult. Authors described identical machines, with lights and noises, or machines hidden in pouches, but it was not clear whether or not women, or those providing care, really had no idea of whether or not they were using an active device. None of the authors provided qualitative data regarding the success of blinding. The issue of blinding is likely to be important, as lack of blinding or inadequate blinding may affect both outcome assessment and the behaviour of care providers (for example, a midwife who was aware, or suspected, that a woman had received an inoperative machine may have encouraged a woman to accept other analgesia, and this may have affected the results of a trial).

In studies comparing TENS with no intervention, blinding was not attempted.

The lack of blinding, and the lack of information on whether successful blinding was achieved by the use of sham devices, are potential sources of bias in these studies and should be kept in mind when interpreting results.

Incomplete outcome data

In most of the studies, levels of attrition were relatively low, although even where there was modest attrition, women may have been excluded for reasons associated with outcomes. For example, in the study described by Bundsen 1982, four of the original sample of 28 were excluded from the analyses as they went on to request an epidural (two women) or to have a caesarean section (two women). In the studies by Harrison 1986 and Thomas 1988 there were high levels of missing data for some outcomes.

Other potential sources of bias

Several of the studies had unbalanced study groups. The trial by Bundsen 1982 included nine women in the control group compared with fifteen in the intervention group. This difference may have occurred by chance, but nevertheless it means that results are difficult to interpret. In some studies there were unequal numbers of primiparous and multiparous women in the two study groups (Nesheim 1981; Thomas 1988; Tsen 2000). In the Tsen 2000 trial, 30% of the women in the intervention group were nulliparous compared with 80% in the control group. Again, these differences may have occurred by chance, but the way that primi- and multiparous women experience pain in labour may be different, so this imbalance in groups affects the interpretation of results. Several of the studies included only small samples, and while this may not be a source of bias, it does have an impact on whether or not the results can be generalised. Most study authors did not report the numbers of women approached compared with those women actually recruited to studies and randomised.

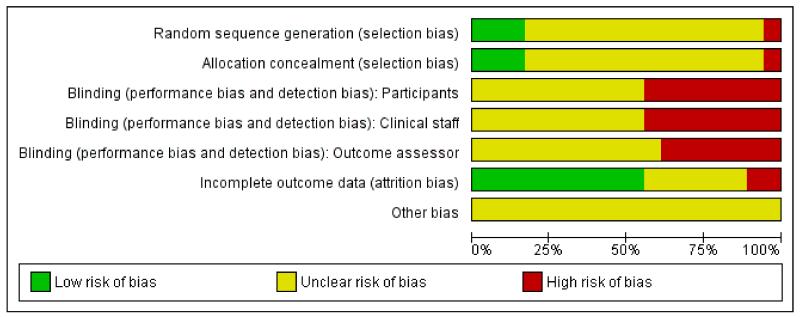

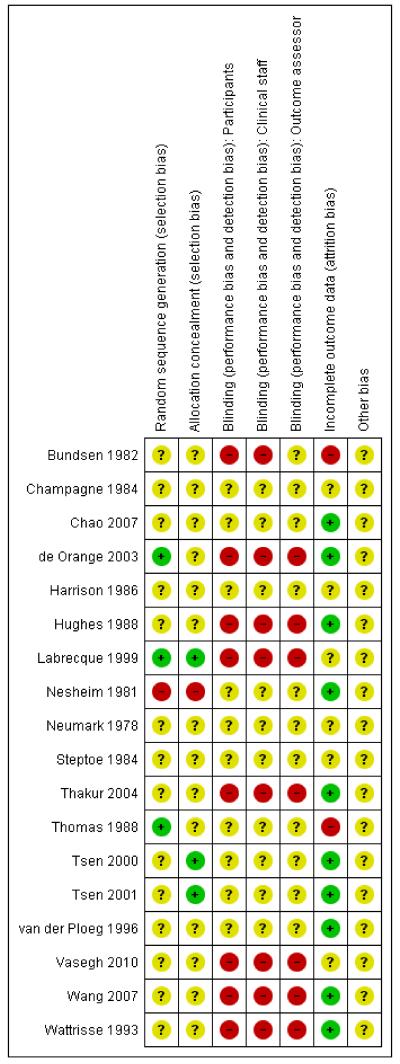

We have summarised overall results for risk of bias in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

Figure 1. Risk of bias graph: review authors’ judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Figure 2. Risk of bias summary: review authors’ judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Effects of interventions

Presentation of results

The review includes three different types of TENS devices: TENS applied to the back (operated by women); TENS applied to acupuncture points (applied by trained staff); and TENS applied to the cranium (applied by trained staff). In addition, the control conditions also varied; TENS was compared with usual care or placebo devices; in three studies TENS was an adjunct to epidural analgesia; and in one study TENS was compared to sterile water injection.

To simplify the way we have reported results we have presented together, in one comparison, those studies where TENS was compared with routine care or placebo devices. For each outcome, studies examining each type of TENS machines (TENS to the back, acupuncture points or cranium) have been grouped together and combined in meta-analyses (with sub-totals for each group). We have not pooled the results for different types of devices, and similarly, results in the text are reported separately for different types of TENS.

The results from studies where TENS was an adjunct to epidural or where compared to sterile water injections, have been examined in a separate comparisons.

For some outcomes there were high levels of heterogeneity and these results should therefore be examined with caution. For analyses where there are high levels of unexplained heterogeneity, we have used a random-effects model.

TENS versus placebo or usual care (14 studies, 1256 women)

Primary outcomes

Pain in labour

There was considerable variation in the way that pain was measured in the included studies. We have combined studies where pain was measured either as a dichotomous variable or as a continuous variable in separate analyses, but in view of the fact that definitions and measurement scales varied between studies, results should be viewed with some caution.

Severe pain in labour

Two studies including 147 women compared the numbers of women reporting severe pain during labour for women receiving TENS (to the back) versus placebo or routine care; women in the TENS group were less likely to report severe pain, but the evidence of a difference between groups did not reach statistical significance (average risk ratio (RR) 0.67, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.32 to 1.40, P = 0.28 (as there was substantial heterogeneity for this outcome we used a random-effects model)), Analysis 1.1.

Two studies (including 190 women) examining TENS applied to acupuncture points also found that women in the TENS group were less likely to report having severe pain compared with controls (RR 0.41, 95% CI 0.31 to 0.54), Analysis 1.1.

Pain scores

Two studies examining TENS to the back (including 299 women) used visual analogue scales to measure women’s pain in labour, the evidence of a difference between groups was not statistically significant (average standardised mean difference (SMD) −1.01, 95% CI −3.00 to 0.97, (as there was substantial heterogeneity for this outcome we used a random-effects model)), Analysis 1.2. (Both studies measured pain on scales with scores recorded in millimetres, it was not clear how the 10 cm scale was labelled in the Labrecque 1999 study, and the length of the scale (maximum score) was not clear in the Thomas 1988 study. The standard deviations reported for the Labrecque 1999 study are much smaller than would be expected with this type of scale, therefore results should be interpreted with caution.)

Satisfaction with pain relief in labour

There was variability in the way satisfaction with pain relief was defined in different studies and again, we would advise caution in the interpretation of results.

Five studies (including 452 women) examining TENS to the back compared with placebo TENS or routine care collected information on women’s satisfaction with pain relief in labour. While women in the TENS group were more likely to express satisfaction the difference between groups did not reach statistical significance (RR 1.25, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.60), Analysis 1.3. The single study (including 90 women) examining TENS to acupuncture points and measuring satisfaction with pain relief reported that women in the TENS group were more satisfied with their pain relief compared with women in the control group (who received no pain relief whatsoever) (RR 4.10, 95% CI 1.81 to 9.29), Analysis 1.3. Several studies examining TENS to the back versus placebo/sham TENS included an outcome relating to women’s willingness to use TENS again in a future labour. In four studies, including 583 women, those in the active TENS group were more likely to be willing to use TENS again in a future labour compared with women with inactive machines (average RR 1.50 95% CI 1.23 to 1.83, (as there was substantial heterogeneity for this outcome we used a random-effects model)), Analysis 1.4. While 63% of women in the active TENS group would use TENS again, 41% using inactive devices reported that they too would be willing to use TENS in a future labour (unweighted percentages). A single study, including 100 women, comparing TENS versus placebo TENS to acupuncture points similarly reported that women in the active TENS group would be more likely to express a willingness to use TENS again (RR 1.45 95% CI 1.18 to 1.79), Analysis 1.4. (Although again, relatively large numbers in the placebo group expressed positive views about the intervention).

Secondary outcomes

Duration of labour

There was no significant evidence of a difference in the duration of either the first and second stages of labour (various definitions) for women receiving TENS to the back or to acupuncture points compared with women in control groups (Analysis 1.10; Analysis 1.11).

Sense of control in labour

One study reported that here was no significant evidence of a difference in reported sense of control during labour for women receiving TENS to the back compared with women receiving standard care (Labrecque 1999). Standard deviations reported in the paper appeared inconsistent and we have therefore not included data in an analysis.

Use of other analgesia and augmentation of labour

There was no significant evidence of any differences in the numbers of women receiving epidural analgesia for women in control groups compared with women receiving TENS to back (average RR 0.99 95% CI 0.59 to 1.67) (as there was substantial heterogeneity for this outcome we used a random-effects model), Analysis 1.12, or acupuncture TENS (average RR 0.40, 95% CI 0.08 to 1.97) Analysis 1.12. There was a considerable difference in the use of epidural analgesia in the trial examining the use of Limoge current to the cranium, with nine of ten women in the control group going on to have an epidural, compared with only one women of ten in the experimental group Analysis 1.12.

There was no evidence of significant differences between groups in terms of the numbers receiving other analgesia, or in the mean amounts of other analgesia used (Analysis 1.7; Analysis 1.8).

Few studies collected information on the augmentation of labour and there was no evidence of differences between groups (Analysis 1.9)

Mode of delivery

In eight studies (including 868 women) comparing TENS to the back versus placebo TENS or routine care, there was no significant evidence of a difference between TENS and control groups in the numbers of women undergoing caesarean section (RR 1.35, 95% CI 0.84 to 2.17), Analysis 1.5. In the single study (100 women) including this outcome where acupuncture TENS was compared with a placebo, again there was no strong evidence of a difference between groups (RR 1.50 95% CI 0.26 to 8.60), Analysis 1.5. In the study examining the use of Limoge current to the cranium, one woman in both the experimental and control groups had a caesarean section.

Seven studies examining TENS to the back (840 women) reported the numbers of women having assisted vaginal deliveries. There was no evidence of a difference between groups (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.56 to 1.19), Analysis 1.6. In the single study (100 women) looking at TENS to acupuncture points versus placebo, women in the TENS group were more likely to have an assisted delivery although the confidence intervals were very wide for this outcome (RR 4.50, 95% CI 1.02 to 19.79), Analysis 1.6. In the study examining the use of TENS to the cranium, there was no evidence of a difference between groups for this outcome.

Satisfaction with childbirth experience

There was no significant evidence of a difference in satisfaction with labour and delivery for women in the control group compared with women receiving TENS to the back in a single study with a small sample (Labrecque 1999). Standard deviations reported in the paper appeared inconsistent and we have therefore not included data in an analysis.

Outcomes for babies

There was little information in the included studies on outcomes for babies. No study reported information on admission to NICU/SCBU or infant outcomes at long-term follow-up. None of the studies reported information on the number of babies with Apgar scores less than seven at five minutes (pre-specified outcome). While there was information provided on mean Apgar scores in some studies, these data are very difficult to interpret. Similarly, the number of babies with cord pH less than 7.1 was not reported, but again mean values were sometimes reported but were difficult to interpret. Two studies included information on fetal distress; small numbers of babies were reported as experiencing distress and no statistically significant differences between groups were reported (Analysis 1.13). Electrical interference with fetal heart rate monitoring equipment was reported in one case in one study (Hughes 1988).

Other pre-specified outcomes

No studies reported information on cervical dilatation on admission to hospital; breastfeeding; effect on mother/baby interaction; or cost. All of the studies included women randomised in early labour in hospital settings. No studies examined the use of TENS at home in early labour and so there was no information on whether the use of TENS delayed admission to hospital. No studies reported side effects of TENS.

TENS as an adjunct to epidural analgesia (three studies, 200 women)

Three studies examined TENS as an adjunct to epidural. In two studies TENS was applied to the back (Tsen 2000; Tsen 2001) and in one, TENs was applied to the cranium (Wattrisse 1993).

Primary outcomes

Two studies (including 80 women) examined TENS to the back as an adjunct to epidural analgesia, and pain scores measured at 60 minutes after insertion of the epidural were very similar in the active TENS and placebo groups (mean difference (MD) 0.23, 95% CI −8.71 to 9.16), Analysis 2.1. The study examining cranial TENS with epidural compared with epidural alone also revealed no significant differences in pain scores between groups (Analysis 3.1).

Secondary outcomes

In the studies where TENS was used as an adjunct to epidural there was no evidence of a difference between groups in terms of the number of women undergoing caesarean section or having assisted deliveries (Analysis 2.2; Analysis 2.3; Analysis 3.2; Analysis 3.3). In the single study (120 women) examining the use of cranial TENS as an adjunct to epidural analgesia, the length of the first stage of labour was similar in both groups (Analysis 3.6). In this study, the analgesic effect of the first dose of epidural lasted longer when cranial TENs was applied as an adjuvant therapy (Analysis 3.4), but this did not result in any overall reduction in the total dose of epidural used by women in the two groups (Analysis 3.5). The following outcomes were not reported in studies: cervical dilatation on admission to hospital; breastfeeding; effect on mother/baby interaction; or cost. All of the studies included women randomised in early labour in hospital settings. No studies examined the use of TENS at home in early labour and so there was no information on whether the use of TENS delayed admission to hospital. No studies reported side effects of TENS.

TENS versus sterile water injection (one study, 23 women)

Primary outcomes

Pain intensity

One small study examining TENS to the back compared with sterile water injection used visual analogue scales to measure women’s pain in labour (millimetres) Labrecque 1999. Women in the TENS group were more likely to have a higher mean pain score in labour than women in the sterile water injection group (SMD, 5.45, 95% CI 3.49 to 7.42), Analysis 4.1. (The study measured pain on a scale with scores recorded in millimetres, it was not clear how the 10 cm scale was labelled and the reported standard deviations are much smaller than would be expected with this type of scale, therefore results should be interpreted with caution).

Secondary outcomes

Sense of control in labour

There was no significant evidence of a difference in sense of control during labour for women receiving TENS to the back compared with women receiving sterile water injections (Labrecque 1999). Standard deviations reported in the paper appeared inconsistent and we have therefore not included data an analysis.

Use of other methods for pain relief in labour

There was no significant evidence of any differences in the numbers of women receiving epidural analgesia for women in the TENS group compared with women receiving sterile water injections (RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.64 to 1.80), Analysis 4.2.

Caesarean section

There was no significant evidence of any difference in the numbers of women undergoing caesarean section for women in the TENS group compared with women receiving sterile water injections (RR 7.62, 95% CI 0.46 to 126.40), Analysis 4.3.

Satisfaction with childbirth experience

There was no significant evidence of a difference in satisfaction with labour and delivery for women receiving TENS to the back compared with women receiving sterile water injections (Labrecque 1999). Standard deviations reported in the paper appeared inconsistent and we have therefore not included data in an analysis.

The following outcomes were not reported in studies: satisfaction with pain relief during labour; duration of labour; augmentation of labour; induction of labour; assisted vaginal birth; side effects; cervical dilatation on admission to hospital; breastfeeding; effect on mother/baby interaction; Apgar score less than seven at five minutes; cord blood pH less than 7.1; adverse events; admission to NICU/SCBU; infant outcomes at long-term follow-up; or cost.

Sub-group analysis

We had intended to carry out sub-group analysis examining the effect of TENS in early versus active labour, however, the studies did not provide consistent definitions of stage of labour and there was variability in inclusion and exclusion criteria. One study (Thomas 1988) provided information on pain scores in early and late labour; while scores were higher in later labour there was no evidence of any difference between women in the TENS and control groups at either stage (Analysis 5.1). One small study (Bundsen 1982) examined whether women reported severe pain in early and later labour and suggested that TENS was associated with fewer reports of severe pain in the later stages of labour (Analysis 5.2).

Few of the studies provided a breakdown of findings by parity. Four of the studies included primiparous women only (Champagne 1984; Steptoe 1984; Wang 2007; Wattrisse 1993); the rest included both primiparous and multiparous women. For pain outcomes, only one study reported separate breakdowns for primiparous and multiparous women and no differences were apparent between subgroups (Analysis 6.1: Analysis 6.2.)

In this updated version of this review we planned subgroup analysis examining possible differences between women who had spontaneous versus induced labours, term versus preterm births and continuous support in labour versus no continuous support in labour. Insufficient information was reported in the included studies to carry out this planned analysis.

Sensitivity analysis

We had intended to carry out sensitivity analysis excluding studies with high risk of bias from analyses to see if this affected results. However, few of the included studies provided sufficient information on study methods to allow us to separate out those studies with low and high risk of bias. If we assume that those studies failing to provide information (or providing only limited information) on, for example, allocation concealment were at high risk of bias, then all but three of the included studies would be excluded in the sensitivity analyses (and two of the studies with adequate information and methods examined TENS as an adjunct to epidural analgesia).

DISCUSSION

Summary of main results

There is some evidence from the studies included in this review that women receiving TENS were less likely to report experiencing severe pain in labour compared with women in control groups. However, the evidence was not strong and was not consistent. In studies where women rated their pain on visual analogue scales, there was no significant evidence of differences between groups. There was no evidence of differences between groups in their requirements for other types of pain relief, including epidural analgesia (except for one study examining the use of cranial TENS). Three studies examining the use of TENS with epidural suggest that TENS is not an effective adjuvant therapy when used along-side epidural or combined spinal epidural analgesia.

We did not find consistent evidence that women receiving TENS were more satisfied with their pain relief in labour compared with controls. At the same time, approximately two-thirds of women receiving TENS reported that they would be willing to use TENS again in a future labour, although this also applied to approximately 40% of those women who had been provided with inactive placebo devices.

TENS seems to have little impact on other labour outcomes. There was no strong evidence that the use of TENS made any difference (in either direction) to the mode of delivery, to the length of labour or to obstetric interventions such as augmentation. Few studies collected information on outcomes for babies, and although these studies did not suggest that TENS is associated with harm, much larger randomised and observational studies would be needed to establish the safety of TENS. There was very limited information on several important outcomes including: breastfeeding, effect on mother/baby interaction, side effects, admission to NICU/SCBU, infant outcomes at long-term follow-up, number of babies with Apgar scores less than seven at five minutes and number of babies with cord pH less than 7.1

We had hoped to examine whether the use of TENS at home in early labour would delay admission to hospital; none of the included studies provided information on this outcome.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The studies included in this review were carried out in a variety of countries and settings and this may increase their applicability; however they included relatively small samples and altogether have included only 1456 women. The studies had varied inclusion and exclusion criteria, but tended to include women at term, in spontaneous labour and at low obstetric risk. Women requesting epidural analgesia at the outset were generally excluded although one study examined the effects of TENS before epidural, and two looked at TENS as an adjunct to epidural. Women who had other preferences regarding analgesia may also have been excluded. Most studies did not provide information on the numbers of women approached compared with those actually recruited and randomised. Without such information it is difficult to judge the generalisability of findings.

Two studies examined the use of acupuncture TENS; it was not clear whether in these study hospitals acupuncture was a standard and accepted part of care, nor was it clear whether staff applying the technology were highly skilled and trained, so as to reduce the likelihood of the technology being adopted elsewhere.

It was very difficult to assess the applicability of findings from the included trials because of the wide variety in care received by women in both the TENS and control groups. In some studies TENS was offered alone, in other studies it was an adjuvant therapy. Hence, some women (in one or both groups) had free access to other forms of pain relief, while others may have been denied any other analgesia. So when women expressed satisfaction with their pain relief, it was not clear what exactly women were satisfied with; in one study, for example, all women received pethidine irrespective of group allocation or whether or not they requested it. In some trials, routine management included amniotomy and early oxytocin to augment labour; such interventions are known to have an impact on women’s experience of pain. While most of these studies included women randomised in early labour, there were some inconsistencies; sometimes this was defined as cervical dilatation less than, for example, 5 cm. In another study, inclusion criteria was for women with cervical dilation greater than 4 cm; such variability limits our ability to say whether TENS is helpful in early as opposed to later labour, as there was no clarity about what this means, or when TENS was applied either within or between studies. It is important that in interpreting results, readers examine the characteristics of included studies to appreciate these differences in care.

We have already mentioned the variable ways in which some outcomes were measured in the studies included in the review; for example, the wording of questions relating to satisfaction with pain relief in labour varied between studies. Outcomes such as the length of the first stage of labour are particularly difficult to interpret, as there are no hard and fast rules for determining the starting point of labour. In some studies the start was marked by a given degree of cervical dilation, in others it coincided with hospital admission (and of course, the point at which a woman decides to go to hospital will depend on many factors including her level of anxiety, time of day, distance from the hospital, cultural attitudes, local hospital policy as well as her obstetric history and physiological state). While we have pooled results from such studies, we recognise that differences in the way outcomes have been measured may affect results.

Quality of the evidence

The risk of bias in these studies was generally high. Few studies provided clear information about sequence generation or methods used to conceal group allocation; in the absence of a clear description of methods, the assumption must be that a study is at high risk of bias. While several of the studies claimed that women and care providers were blind to group assignment, these claims must be viewed with some skepticism. Women who have used TENS are aware that the pulses can be felt as a tingling or buzzing on the skin. While some studies specifically excluded women with previous experience of TENS, it is likely that women would have discussed the technology with others, and may well have been aware that they were using an inactive device. It is also likely that women using inactive devices will have reported the fact that they could feel nothing to those ‘blinded’ midwives providing care and recording outcomes. Although high levels of attrition were not a problem in most of these studies, even relatively low levels of post-randomisation exclusions are likely to have an impact on results if women are excluded for reasons that are likely to relate to outcomes (e.g. women who went on to have a caesarean section, or an epidural were excluded from the analysis in one study). Again, readers are advised to examine the tables of risk of bias to assist in interpreting the results of the review.

Potential biases in the review process

The possibility of introducing bias was present at every stage of the reviewing process. We attempted to minimise bias in a number of ways; two review authors assessed eligibility for inclusion, carried out data extraction and assessed risk of bias. Each worked independently. Nevertheless, the process of assessing risk of bias, for example, is not an exact science and includes many personal judgements. Further, the process of reviewing research studies is known to be affected by prior beliefs and attitudes. Work examining bias in the peer reviewing process has suggested that the content of reviews may make them more or less susceptible to observer bias, and studies examining “alternative” therapies, such as TENS, may be particularly prone to this sort of bias. In a study where peer reviewers who had written editorial or opinion pieces for or against TENS were asked to assess the methodological quality of a study about TENS, reviewers’ assessments tended to reflect their prior beliefs (Ernst 1994). It is difficult to control for this type of bias in the reviewing process.

While we attempted to be as inclusive as possible in the search strategy, the literature identified was predominantly written in English and published in North American and European journals. We are also aware that publication bias is a possibility, as the review includes several small studies reporting a number of statistically significant results. Although we did attempt to assess reporting bias, constraints of time meant that this assessment relied on information available in the published trial report and thus, reporting bias was not usually apparent.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

A number of other reviews have examined the use of TENS in labour (Carroll 1997; Gentz 2001; Simkin 1989) and a Cochrane review has examined the use of TENS for other types of pain (Nnoaham 2008). There are some points on which all agree; the evidence relating to TENS is frequently methodologically weak, inconsistent and not easy to interpret. The review by Carroll 1997 et al was used to underpin recent intrapartum care practice guidelines in the UK (NICE 2007). These guidelines concluded that TENS was NOT effective in established labour and there was no evidence that it was effective in early labour, and that TENS should not, therefore, be offered to women in established labour. Our conclusions are not the same. We accept that the results we have described are inconsistent. The studies included in the review do not, in general, demonstrate that compared with controls, women receiving TENS had significantly lower pain scores, or required less pharmacological analgesia. Nevertheless, the majority of women were willing to use TENS again. The experience of pain is complex. There is no simple relationship, for example, between objectively measured physiological changes, women’s experience of pain, and their satisfaction with pain relief. For whatever reasons, some women find using TENS in labour helpful. Whether or not the usefulness of TENS is confined to the very earliest stages of labour, or is only helpful as an adjuvant therapy, is not known. The data available to us allowed only very limited subgroup analysis of differences in early and late labour. The variability in inclusion criteria, and the stage of labour at which TENS was applied, did not allow us to draw any conclusions about these matters, except perhaps that TENS is not useful as an adjunct to epidural analgesia. All of the studies included in this review recruited women after admission to hospital; we do not know whether TENS would be helpful to women at home so as to delay hospital admission. None of the studies included a cost analysis, so it is not clear whether TENS is a cost-effective technology.

AUTHORS’ CONCLUSIONS

Implications for practice

There is some evidence that women using TENS in labour are less likely to rate their pain as severe, but the evidence is neither strong nor consistent. Women using TENS applied to the back (and many using placebo devices) were willing to use TENS in future labours. The relative acceptability of placebo devices may suggest that the device offers a useful distraction, and the fact that women themselves operate the device may enhance a woman’s sense of control. The findings regarding the use of TENS to acupuncture points are positive, but only two studies have evaluated this intervention and the fact that the technology is applied by staff trained in acupuncture techniques may limit its implementation. Many obstetric units have self-operated TENS units for application to the back available. TENS does not seem to increase the use of other interventions or cause harm to mothers or babies. Women should be offered the choice of using TENS (with or without other analgesia) at whatever stage of labour they think it might help.

Implications for research

The interpretation of findings in this review was difficult because of the limited information study authors provided on methods, the variability in outcomes measured, and in the instruments used to measure outcomes. There was no information on the costs associated with using TENS or on the use of TENS in very early labour. The side effects of TENS were not generally reported. Overall, there is relatively little background information on the use of TENS. A small number of surveys of obstetric units shed some light on where TENS is available, but this information is limited (McMunn 2009). We do not know how many (or which) women are offered TENS as part of their care in labour, or at what stage in labour it is offered. We do not know whether TENS is routinely discussed as part of childbirth preparation classes or about women’s knowledge about TENS in labour. There are various specifications for devices; we do not know whether some devices are more effective than others. TENS units are commercially available and it would be useful for women to have information to evaluate the claims made by manufacturers. There are a number of implications for research. Survey information is needed from obstetric units so that there is a clearer picture of the current use of TENS. Information is needed on costs and the types of units available. Most of the studies included in the review were small and all were carried out in hospitals. A large-scale trial focusing on the early stages of labour would address some of the unanswered questions.

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY.

TENS (transcutaneous nerve stimulation) for pain relief in labour

TENS is a device that emits low-voltage currents and which has been used for pain relief in labour. The way that TENS works is not well understood. The electrical pulses are thought to stimulate nerve pathways in the spinal cord which block the transmission of pain. In labour the electrodes from the TENS machine are usually attached to the lower back (and women themselves control the electrical currents using a hand-held device) but TENS can also be applied to acupuncture points or directly to the head. The purpose of the review was to see whether TENS is effective in relieving pain in labour. The review includes results from 17 studies with a total of 1466 women. Thirteen studies examined TENS applied to the back, two to acupuncture points and two to the cranium (head). Results show that pain scores were similar in women using TENS and in control groups. There was some evidence that women using TENS were less likely to rate their pain as severe but results were not consistent. Many women said they would be willing to use TENS again in a future labour. TENS did not seem have an effect on the length of labour, interventions in labour, or the well-being of mothers and babies. It is not known whether TENS would help women to manage pain at home in early labour. Although it is not clear that it reduces pain, women should have the choice of using TENS in labour if they think it will be helpful.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Dr Lawrence Tsen who provided helpful unpublished information on two studies included in the review.

Several papers considered for inclusion in the review were not reported in English. Thanks to Jill Hampson for organising translations; to Lotta Jansson for translating Hulkko 1979, Alice Dowswell for translating de Orange 2003, Neumark 1978 and Tajali-Awal 1995, Angela Cooke for translating Steptoe 1984 and Sara Roden-Scott for translating Champagne 1984 and Wattrisse 1993.

This updated review forms part of a series of reviews focusing on pain management in labour that will be included in a Cochrane overview of reviews (Jones 2011b); contributing reviews share a generic protocol (Jones 2011a). We would like to thank Leanne Jones for her valuable help in updating this review so as to improve consistency between this and other pain management reviews.

Thanks to staff in the editorial office of the Cochrane Collaboration Pregnancy and Childbirth Group for their help in preparing the review, and to the editor and referees for their helpful comments on earlier drafts. Three peers (an editor and two referees who are external to the editorial team), a member of the Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s international panel of consumers and the Group’s Statistical Adviser commented on the first version of this review.

SOURCES OF SUPPORT

Internal sources

The University of Liverpool, UK.

University of Central Lancashire, UK.

External sources

National Institute for Health Research, UK.

NIHR NHS Cochrane Collaboration Programme Grant Scheme award for NHS-prioritised centrally-managed, pregnancy and childbirth systematic reviews: CPGS02

CHARACTERISTICS OF STUDIES

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | RCT. Little information on study design. | |

| Participants | 28 women attending hospital for induction of labour (main indication - postdates). Inclusion criteria: Swedish speaking women with fetus in vertex position. Women were excluded if they “were primarily biased for or against a certain method of pain relief” | |

| Interventions | Intervention group: TENS (2 frequencies) positioned over lower back and/or over the supra-pubic region Comparison group: routine care. Both groups had amniotomy, an oxytocin infusion and access to other pain relief. Most women in both groups had a pudendal block in the second stage |

|

| Outcomes | Lower back and abdominal pain measured hourly in labour. Pain relief assessed by questionnaire, fetal condition at birth assessed by blinded paediatrician | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Described as “randomly assigned”. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Participants |

High risk | Not feasible. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Clinical staff |

High risk | Not feasible. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Outcome assessor |

Unclear risk | Partial blinding: assessment of fetal condition at birth by paediatrician not aware of group assignment. Other outcomes assessed by staff aware of allocation |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

High risk | Two women (of 28) were excluded from analysis as they had a caesarean section. Two further excluded as they had an epidural |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Unbalanced groups for most analyses (9 versus 15). |

| Methods | RCT (described as double blind study). | |

| Participants | Study in France. 20 primiparous women in labour requiring analgesia. |

|

| Interventions | Intervention group: Limoge current to the cranium (applied by trained staff) Control group: Sham device with no Limoge current. |

|

| Outcomes | Use of other analgesia, mode of delivery. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not stated. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not stated. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Participants |

Unclear risk | Described as a double blind study. It is not clear whether women would have been aware that a sham device was being used |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Clinical staff |

Unclear risk | It was stated that the staff applying the TENS were not otherwise providing care for the women |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Outcome assessor |

Unclear risk | Not stated. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Not clear. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Not clear. |

| Methods | Randomised trial with placebo device. | |

| Participants | Hospital obstetrics department in Taiwan. 105 women. Inclusion criteria: women were recruited in the first stage of labour (less than or equal to 5 cm cervical dilatation). Women aged 20 to 40 with term pregnancy, vertex presentation, who had not requested an epidural, planned to give birth vaginally and had no medical or obstetric complications Exclusion criteria: women were excluded if they had previous experience of TENS, acupuncture, epidural analgesia or poor pregnancy outcome |

|

| Interventions | Intervention Group: TENS to 4 acupuncture points on hands and lower legs for 30 minutes and then on request Comparison group: placebo TENS to same positions on hands and legs (the placebo emitted very low level electrical stimulation) |

|

| Outcomes | Pain relief (measured on VAS) at 30 and 60 minutes, mode of delivery, epidural and other analgesic use, progress in labour, willingness to use TENS again, Apgar score at 5 minutes and adverse events | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | “randomly, by permuted blocks with stratification for parity” |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | “neither medical personnel nor participants knew which group was assigned” |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Participants |

Unclear risk | Described as double blind. Placebo device with low current, however, it was not clear whether the attempt to blind women was successful |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Clinical staff |

Unclear risk | Not clear. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Outcome assessor |

Unclear risk | Not clear. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Five of the 105 women randomised delivered before the intervention could take place and were excluded from some of the analysis (included in ITT for main outcome) |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Results relating to pain were difficult to interpret. |

| Methods | Randomised trial. | |

| Participants | Study in Recife, Brazil. 22 women. Inclusion criteria: women with singleton, term pregnancy with cephalic presentation, fetus alive and in good condition Exclusion criteria: women with severe pre-eclampsia, conditions associated with haemorrhage, women planning caesarean or not suitable for epidural analgesia |

|

| Interventions | Intervention group: TENS to back prior to combined spinal epidural Comparison group: combined spinal epidural only (no TENS intervention) |

|

| Outcomes | Mode of delivery, length of time before epidural was requested | |

| Notes | Original paper in Portuguese. Translation used for data extraction | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer-generated table of random numbers. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Sealed envelopes. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Participants |

High risk | Not reported. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Clinical staff |

High risk | Not reported. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Outcome assessor |

High risk | Not reported. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | No apparent loss to follow up apparent. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Only 22 of 73 eligible women were recruited. |

| Methods | RCT. | |

| Participants | 150 women (100 primiparous and 50 parous) recruited in the study hospital in Dublin, Ireland Inclusion criteria: women in their first or third labour admitted to the labour ward with no particular preferences re analgesia Exclusion criteria: women at high risk or requiring monitoring. Women admitted for induction of labour |

|

| Interventions | Intervention: TENS to back. Comparison Group: placebo TENS device. Other analgesia were available on request to women in both groups and other management was as usual |

|

| Outcomes | Pain, requests for other analgesia, cord pH and Apgar score, midwife assessment of pain relief | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Allocated “randomly” to one of the 6 numbered machines. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No information. Machines of similar appearance. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Participants |

Unclear risk | Authors state that women and midwives were not aware which were the active and placebo TENS machines. The numbers on the machines were changed regularly by a 3rd party |