Abstract

Clear cell kidney cancer (CRCC) is initiated typically by loss of the tumor suppressor VHL, driving constitutive activation of HIF-1 and HIF-2. However, whereas HIF-1 has a tumor suppressor role, HIF-2 plays a distinct role in driving CRCC. In this study, we show that the HIF-1α E3 ligase HAF complexes with HIF-2α at DNA to promote HIF-2-dependent transcription through a mechanism relying upon HAF SUMOylation. HAF SUMOylation was induced by hypoxia, whereas HAF-mediated HIF-1α degradation was SUMOylation independent. HAF overexpression in mice increased CRCC growth and metastasis. Clinically, HAF overexpression was associated with poor prognosis. Taken together, our results show that HAF is a specific mediator of HIF-2 activation that is critical for CRCC development and morbidity.

Keywords: HIF, HAF, SUMO, VEGF, OCT-3/4, clear cell renal cell carcinoma, hypoxia, metastasis

Introduction

The hypoxia response promotes the adaptation to low oxygen by shifting cells towards anaerobic metabolism, neovascularization and resistance to apoptosis. Hypoxia occurs in all solid tumors and their metastases, and drives responses that contribute to tumor aggressiveness, such as increased invasion, metastasis and a poorly differentiated phenotype. This occurs largely through activation of the hypoxia inducible factors, HIF-1 and HIF-2, which are central players in the regulation of the physiological and pathophysiological responses to hypoxia (1, 2). HIF-1 and HIF-2 are non-redundant and play unique and complementary roles during bone and vascular development, and also in regulating cellular transcriptional responses to acute and chronic hypoxia (3, 4). In this regard, HIF-1 and HIF-2 can drive distinct downstream target genes and also exhibit antagonism in regulating the hypoxia response (5). The highly divergent outcomes of HIF-1 and HIF-2 signaling on tumor growth and progression occur despite their high degree of similarity in structure and mechanisms of regulation, and appear to be dependent on hypoxic intensity and duration, and other isoform specific HIF regulators that are beginning to be identified (2). We have established that the Hypoxia Associated Factor (HAF) can promote the switch from HIF-1 to HIF-2 dependent signaling, that it achieves by selectively degrading HIF-1α independently of oxygen or pVHL, and promoting HIF-2α transactivation without affecting HIF-2α levels (4, 6).

Clear cell renal cell carcinoma (CRCC) is the most common type of kidney cancer, and is highly refractory to standard chemotherapy and radiation. The etiology of CRCC is uniquely linked to loss of the von Hippel-Lindau (pVHL) tumor suppressor protein, whereby more than 90% of cases of both sporadic and hereditary CRCC show pVHL deficiencies (7–9). pVHL is the substrate recognition component of the E3 ligase complex that targets the oxygen labile HIF-1α and HIF-2α subunits for proteasomal degradation under aerobic conditions. Under hypoxic conditions, or in the presence of pVHL deficiency, HIF-1α and HIF-2α are stabilized, and enter the nucleus where they heterodimerize with HIF-1β, forming the HIF-1 or HIF-2 transcriptional complexes respectively, and activate the transcription of hundreds of genes critical for the adaptation to hypoxia, and for tumor progression (1, 10). pVHL loss-of function is a critical event for CRCC initiation, promoting the constitutive activation of HIF-1 and HIF-2, which play a dominant role in the progression of CRCC (11). Indeed, CRCC is one of the best-perfused of solid tumors due to the overproduction of HIF dependent pro-angiogenic factors, VEGFA and PDGFB. Nevertheless, CRCC tumors still experience relatively low oxygen tensions due to the already low physiological oxygen tensions within the kidney, (CRCC is believed to originate from proximal tubular epithelial cells within the renal cortex), and to the inherent abnormality of the tumor vasculature (12–14).

Converging lines of evidence support a driving role for HIF-2α and not of HIF-1α in CRCC. First, although elevated HIF-1α is apparent in the earliest pre-neoplastic lesions in VHL patients, the appearance of HIF-2α is associated with increased dysplasia and cellular atypia (15, 16). Hence, CRCC cells and tumors can be subdivided into two subtypes: those that express both HIF-1α and HIF-2α (pVHL mutant or pVHL wild-type), or those that express HIF-2α exclusively (pVHL mutant only) (17, 18). Second, overexpression of HIF-2α promotes, whereas overexpression of HIF-1α inhibits, CRCC growth (19–21). Third, inhibition of HIF-2α by shRNA is sufficient to suppress the growth of pVHL null CRCC cells (19, 22). Fourth, Type 2B pVHL mutants, associated with high risk of CRCC, retain some ability to downregulate HIF-1α, but have reduced ability to downregulate HIF-2α, compared to Type 2A pVHL mutants, associated with low risk of CRCC (23, 24). Taken together, the data suggest that there may be a temporal nature to HIF activation in CRCC whereby VHL loss is associated with early elevation of HIF-1α, which then shifts to HIF-2α, which promotes dysplasia and CRCC progression. There is also increasing evidence implicating HIF-1A as a kidney cancer suppressor gene, particularly in advanced CRCC: Loss of heterozygosity in chromosome 14q in the locus spanning HIF1A has been reported in ~40% of human CRCC, where as homozygous deletion of HIF1A was detected in ~50% of CRCC cell lines (25, 26). Although the mechanism of the shift to HIF-2 is unclear, the specific pro-tumorigenic effect of HIF-2α in CRCC may be due its increased potency compared to HIF-1α in driving pro-tumorigenic factors such as Cyclin D1, TGF-α and VEGFA, and in potentiating c-Myc activity, which in contrast is inhibited by HIF-1α (18, 21).

The hypoxia associated factor (HAF, located at 11q13.1) is a mediator of the switch from HIF-1α to HIF-2α, by selectively degrading HIF-1α, and promoting HIF-2α transactivation (4). HAF overexpression enhances the ability of glioblastoma cells (which express both HIF-1α and HIF-2α) to initiate tumors as intracranial xenografts in mice. However, HAF overexpression decreases xenograft tumor growth of HT29 colon carcinoma cells that only express HIF-1α (6). Hence HAF may either inhibit or promote tumor progression, depending on the dominant HIF-α isoform expressed in a given cellular context. However, the mechanism by which HAF elicits its selective effects on HIF-1α and HIF-2α in the context where both HIF-α isoforms are present, remains unknown.

Here, we elucidate the mechanism and regulation of HAF-mediated HIF-2 transactivation. We show that HAF promotes the transcription of a subset of HIF-2 target genes by binding to a DNA consensus site located within close proximity to the HRE, thus forming a transcriptional complex with HIF-2α to drive transcription. Significantly, we demonstrate that the ability of HAF to bind and transactivate HIF-2α is dependent upon HAF SUMOylation, which is induced by exposure to hypoxia. By contrast, the ability of HAF to bind and degrade HIF-1α is independent of HAF SUMOylation. Thus in the context of pVHL loss that results in the constitutive stabilization of HIF-1 and HIF-2, HAF preferentially promotes HIF-2 specific activation, and CRCC patients with high HAF show significantly decreased progression-free survival than those with low HAF. This suggests that HAF may be the determinant of HIF-2 specific activation in CRCC, thus providing a novel avenue for therapy.

Materials and Methods

Tissue culture

A498, 786-0, PANC-1, MIAPaCa-2 and ACHN cells were from ATCC (Manassas, VA) and were maintained in RPMI (A498), and Dulbecco’s MEM (ACHN, 786-0, PANC-1, MIAPaCa-2; Invitrogen Corp, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. The identities of all cell lines were confirmed by the Molecular Cytogenetics Facility at MDACC using STR DNA fingerprinting upon receipt from ATCC. Cells were frozen, thawed and retested after 3 months in culture, after which sells were discarded and a fresh vial thawed. Hypoxic incubations (1% O2) were performed using the In Vivo2 Hypoxia Workstation (Biotrace International Inc, Muncie, IN).

Plasmid construction and transfections

Stable cell lines overexpressing HAF and HAF DM (HAF K94R K141R), or shHIF-2 were generated by retroviral infection of using pMX-IRES-GFP, or pSUPER respectively (27). The pCMVFLAG14 construct was used for transient transfections with HAF or HAF DM (6). The P117 Luc reporter was generated by cloning the P117 sequence (28) upstream of luciferase and a minimal CMV promoter (pGL4.17, Promega Corp, Madison WI). P117 HRE containing the HRE and HIF ancillary sequence (29) was generated by cloning the HRE downstream of P117 (Supplemental methods). HAF-GAL4 fusion protein was generated by ligating full length FLAG-HAF downstream of the GAL4 DNA binding domain using the pBIND plasmid from the Checkmate Mammalian Two-hybrid System (Promega). Transactivation activity was confirmed using the pG5 Luc vector containing five GAL4 binding sites upstream of luciferase, normalized to intronic Renilla luciferase encoded within the pBIND vector. GAL4-VP16 (pBIND-id and pACT-MyoD) was used as positive control according to manufacturer’s protocol. Transient transfections were performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) and cells were assayed 48 hours post-transfection. HIF-2α siRNA duplexes were from Dharmacon (GE Healthcare, Lafayette CO): siGENOME D-004814-02 (DNA oligos were ligated into pSUPER to generate shH2), D-004814-03 (siH2_2). HAF (SART1) siRNA was ON-Target plus SMARTpool (Dharmacon L-017283, siHAF_1), and Silencer #15787 (siHAF_2, Ambion, Life Technologies). Hypoxic exposure was at 1% O2, performed 24 hours post-transfection, and harvested after 16 hours unless otherwise indicated.

Taqman quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated using the RNEasy kit with DNAse I step. TaqMan qRT-PCR was performed using the ABI 7300 system with One-Step RT-PCR Master Mix kit and pre-designed primer/probes, and normalized to B2-microglobulin as previously described (6). Statistical significance was determined using MS Excel (t-test).

Western Blotting, immunoprecipitation (IP) and immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Western blotting was performed using HIF-2α (NB100–122, Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO), actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., CA), HIF-1α (Cell Signaling Technology (CST), Danvers MA), SUMO-1 (CST #4930S), SUMO-2/3 (ab81371, Abcam, Cambridge MA) and HAF antibodies (6, 30). IPs to show SUMOylation of HAF was performed using RIPA buffer (with 20mM NEM) with sonication. Denaturing IP was performed by boiling immunoprecipitated proteins conjugated to protein A beads in 50 µl 1% SDS solution for 5 minutes, resuspending the supernatant in 1 ml of RIPA buffer, and repeating IP with fresh protein A beads overnight. Immunocytochemistry was performed using purified mouse monoclonal anti-HAF antibody raised against GST-HAF432–800 (Biogenes GmbH, Berlin, Germany) and rabbit polyclonal anti-HIF-2α (NB 100–122), with Cy3 goat anti-mouse, and Alexa488 chicken anti-rabbit secondary antibodies respectively (Invitrogen). Images were taken using the Nikon A1Rsi confocal microscrope at a single plane and Z-stack (0.8–1.0 µM). Immunohistochemistry was performed using HIF-2α or HAF mAb antibody, using citrate buffer antigen retrieval (Leica microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL), and the Bond Polymer Intense Detection Kit (Leica Microsystems).

Luciferase assays

These were performed using the Luciferase Dual Glo Assay System (Promega). Activities of reporters were normalized to constitutive Renilla Luciferase (β-actin).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

ChIP assays were performed using 786-0 or PANC-1 cells stably expressing HAF, HAF DM or shHIF-2and the respective empty vector controls pMX-IRES-GFP (Vec) or pSUPER, using the EZ ChIP kit (EMD Milipore, MA). ChIP antibodies were HIF-2α (NB100–122), HAF (6), FLAG (Sigma-Aldrich) and control IgG (Bethyl Biolabs). Semi-quantitative PCR was performed using standard protocols with indicated primer pairs (Supplemental methods). Quantitation was performed using the AlphaView Q Imaging software (Proteinsimple, Santa Clara CA).

In vivo tumor growth studies

Nu/nu nude mice (10 per group) were injected subcutaneously with 107 786-0 cells. Tumor diameters were measured twice weekly at right angles (dshort and dlong) using electronic calipers and tumor volumes calculated by the formula volume = (dshort)2 × (dlong)2 (31). Orthotopic renal models were generated by injection of 5 × 106 786-0 cells (in 50 µl saline) in the right renal sub-capsule of nude mice (6 per group) as described (32). Tumors were harvested after 2 months. Tumor weight was calculated by subtracting the weight of the normal left kidney from the weight of the implanted right kidney.

CRCC Tumor Microarray (TMA) preparation and analysis

The TMA comprised pre-treatment nephrectomy specimens of patients with metastatic Grade III/IV CRCC treated with sorafenib or sorafenib plus interferon (33). All patients showed haploin sufficiency at 3p indicating pVHL deficiency although formal sequencing of VHL was not undertaken. Three cores per patient in replicate arrays were stained for HIF-1α (1:100; 2015-1, Epitomics, Burlingame CA), HIF-2α or HAF. Image capture and analysis for HIF-1α and HIF-2α were performed using the Ariol system (Applied Imaging, San Jose, CA). Cores were scanned using TMA Navigator software (Applied Imaging, Grand Rapids MI). Regions of viable tumor were gated, excluding areas of non-viable tumor and non-tumor tissue. Image capture for nuclear HAF was performed using the Vectra multispectral slide analysis system, and analyzed using the in Form image analysis software (both from Perkin Elmer, Caliper Life Sciences, Waltham, MO). The percentage tumor cell involvement of HIF-1α, HIF-2α or HAF was determined by a pathologist (FAM).

Statistical Analysis

These were performed using IBM SPSS (Vs.19) comparing nuclear HAF staining and progression free survival (PFS) with patients stratified to groups expressing low and high HAF respectively. Log-Rank test and Cox regression was used to compute p-value for Kaplan Meir curves and hazard ratios respectively.

Results

HAF promotes the transcription of HIF-2 target genes

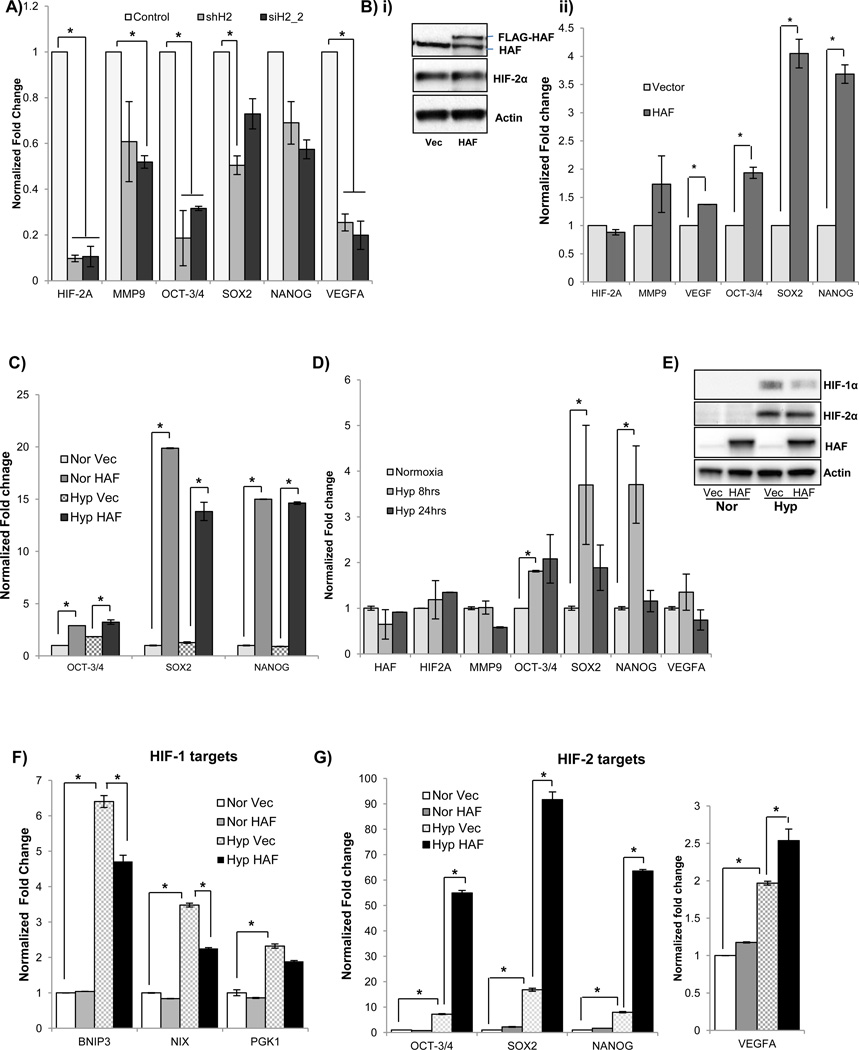

CRCC cells offer a unique opportunity to study the effects of HAF on HIF-2α, independently of HIF-1α, as many CRCC cells do not express HIF-1α (34). CRCC also provides a setting in which HIF-2α has a clear driving role in tumor progression. To identify HIF-2 target genes in 786-0 CRCC cells (pVHL deficient, constitutive HIF-2α, no HIF-1α), we stably expressed HIF-2α shRNA (shHIF2) or empty vector (pSUPER) in these cells. Knockdown of HIF-2α in 786-0 shHIF2 cells decreased the transcription of a panel of HIF-2 genes compared to the empty vector control, confirming that these genes were HIF-2 dependent (Fig 1A). Similar results were obtained by transient transfection of parental 786-0 cells with a different siRNA duplex targeting HIF-2α and normalized to a non-targeting control siRNA (siH2_2; Fig. 1A). To investigate the role of HAF specifically on HIF-2 dependent transcription, we overexpressed HAF in the 786-0 cells and found that it induced the transcription of the aforementioned HIF-2 target genes without affecting HIF-2α levels (Fig. 1B). Among these genes, we observed that the greatest induction due to HAF overexpression was in the levels of the pluripotency genes OCT-3/4, SOX2 and NANOG. The induction of these genes was also observed in 786-0 cells stably overexpressing HAF, and this occurred in both normoxia and hypoxia (Fig. 1C). Similar results were obtained using A498 CRCC cells (pVHL deficient, constitutive HIF-2α; Supplemental data S1A–B). Consistent with constitutive HIF-2α expression due to loss of pVHL, the 786-0 cells did not show any general induction of HIF-2 target genes upon exposure to 16 hours’ hypoxia. However, we did observe significant temporal inductions of OCT-3/4, SOX2 and NANOG after 8 hours’ exposure to hypoxia (Fig. 1D), suggesting an alternate, pVHL independent hypoxia sensing mechanism for these genes. To investigate the impact of HAF overexpression in cells that have functional pVHL, and therefore hypoxia-inducible HIF-1α and HIF-2α, we overexpressed HAF in the ACHN CRCC cells. Here, HAF overexpression decreased the levels of HIF-1α protein without affecting HIF-2α levels, and attenuated the hypoxic induction of HIF-1 specific target genes, BNIP3, BNIP3L (NIX) and PGK1(Fig. 1E–F). HAF overexpression also significantly induced transcription of the HIF-2 target genes OCT-3/4, SOX2, NANOG and VEGFA to a level above that induced by hypoxia (Fig. 1G). Hence, HAF promotes the shift towards HIF-2 dependent transcription in both pVHL wild-type and pVHL deficient CRCC cells.

Figure 1.

The effect of HIF-2α knockdown using stable expression of HIF-2 shRNA or transient transfection with an alternative HIF-2α siRNA duplex on levels of HIF-2α transcript and a panel of HIF-2 target genes as determined by quantitative RT-PCR normalized to stably or transiently expressed non-targeting controls respectively. B) The effect of transient HAF overexpression in 786-0 cells on, i) HIF-2α protein levels determined by western blotting, and ii) transcription of HIF-2α and a panel of HIF-2 target genes as determined by qRT-PCR normalized to vector control. C) The effect of stable HAF overexpression in 786-0 cells on transcription of a subset of HIF-2 target genes in both normoxia and hypoxia as determined by qRT-PCR normalized to vector cells in normoxia. D) qRT-PCR showing effect of duration of hypoxic exposure on the transcription of the panel of HIF-2 target genes. Data shown are the mean of at least 2 independent experiments ± SE, *p < 0.05. E–F) The effect of HAF overexpression in ACHN cells on, E) HIF-1/2α protein levels by Western blotting, and, F) HIF-1, or G) HIF-2 dependent target genes in normoxia and hypoxia. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments ± SE, *p < 0.05.

HAF promotes the binding of HIF-2α to the HRE

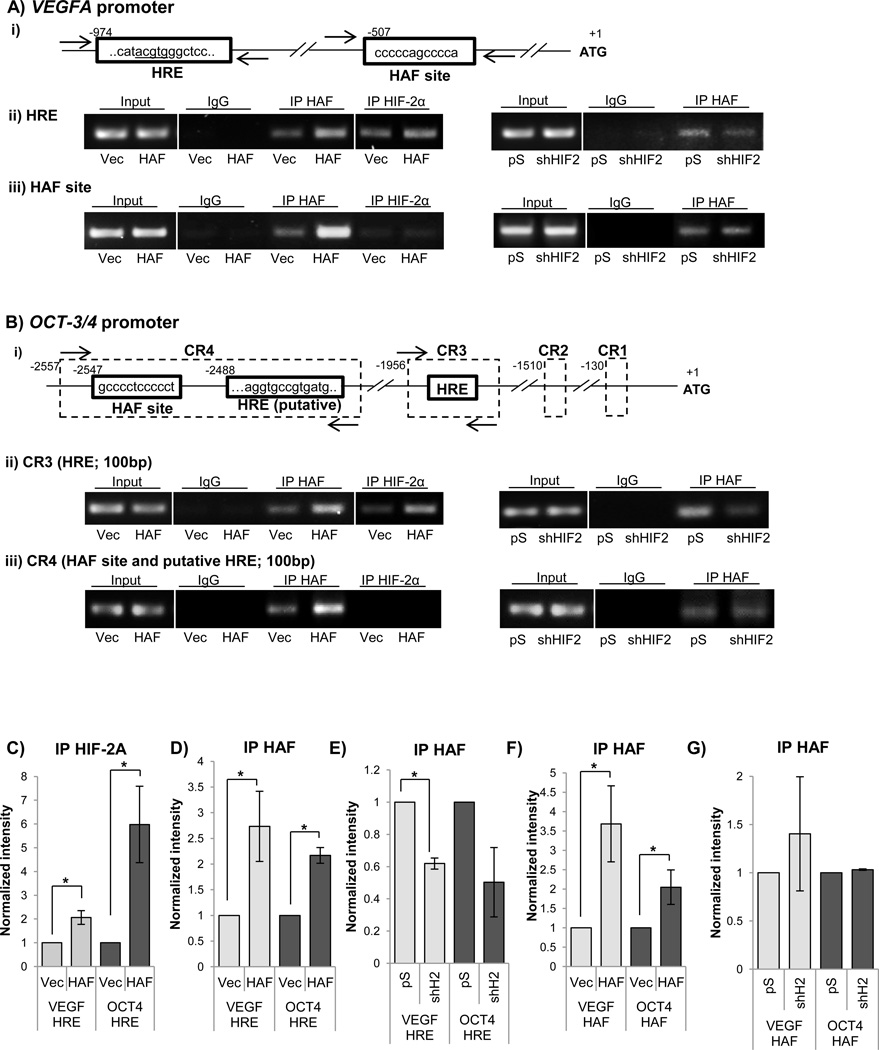

To determine the mechanism by which HAF promotes HIF-2 transcription, we investigated the impact of HAF overexpression on HIF-2α DNA binding activity within the promoter of VEGFA. HAF has been shown to bind the VEGFA promoter at a site located approximately 600bp downstream of the HRE (Fig. 2A i) (35). Using specific primers flanking the VEGFA HRE in 786-0 cells (Fig. 2A), we show that HAF overexpression significantly increased the binding of HIF-2α to the HRE (Fig 2A ii left panel, 2C). Additionally, HAF itself bound the HRE but binding was reduced when HIF-2α was knocked down, suggesting that HAF binding to the HRE is HIF-2α-dependent (Fig. 2A ii, right panel, 2E). Using specific primers flanking the HAF site in the VEGFA promoter, we confirmed that both endogenous and overexpressed HAF bound to the HAF site (Fig. 2A iii, left panel, 2D, F). HAF binding to this site was unchanged when HIF-2α was knocked down suggesting that HAF binding to the HAF site is HIF-2α independent (Fig. 2A iii, right panel, 2G). By contrast, we did not detect any binding of HIF-2α to the HAF site (Fig. 2B iii, left panel).

Figure 2.

(A) i) Schematic of regulatory regions in VEGFA promoter showing the hypoxia responsive element (HRE) and the HAF DNA binding site. Numbers indicate nucleotides with the transcription start site indicated by +1. Arrows indicate binding location of primers used for semi-quantitative PCR. A ii) and iii) are the representative results of ChIP assay followed by semi-quantitative PCR (30 cycles) showing the effects of HAF overexpression (left panel) and stable HIF-2α knockdown (right panel) on binding of HAF or HIF-2α to the, ii) HRE and iii) HAF site in the VEGFA promoter. B) i) Schematic of the OCT-3/4 promoter showing conserved regions (CRs) 1–4, HREs and the putative HAF binding site. ChIP assays were performed as in A to show the effects of HAF overexpression (left panel) and HIF-2α knockdown (right panel) on binding of HAF or HIF-2α to the ii) HRE within CR3 and iii) putative HAF binding site and HRE within in CR4. C–G) Quantitation of ChIP results obtained from 3 independent experiments. Results are the mean ± SE, *p<0.05.

To investigate another HIF-2 dependent target gene, we examined the promoter sequence of the stem cell factor,OCT-3/4. Four conserved regions (CRs) between the promoters of the human, mouse and bovine orthologs of OCT-3/4 have been reported (36). Although six putative HREs have been identified with in these CRs, only two (CR3 and CR4) have been described to bind HIF-2α (Fig. 2B i) (37). We found that endogenous HIF-2α bound the OCT-3/4 promoter within the HRE on CR3, but not within CR4, and the binding of HIF-2α to CR3 was significantly increased when HAF was overexpressed (Fig. 2B ii, iii, 2C). Similar to the VEGFA promoter, HAF overexpression increased its recruitment to the CR3 HRE, but its binding was decreased when HIF-2α was knocked down, suggesting, again, that the binding of HAF to the HRE is HIF-2α dependent (Fig 2Bii right panel, 2E). HIF-2α binding to the HRE in CR4 was undetectable, and hence the impact of HAF overexpression on HIF-2α binding to this site could not be assessed (Fig. 2B iii, left panel). Hereafter, the HRE within CR3 will be referred to as the OCT-3/4 HRE. Since HAF binds to similar sites (CCCCCACCCCC and CCCCCAGCCCC) within the EPO and VEGFA promoters respectively (35, 38), we searched the CRs within the OCT-3/4 promoter for putative HAF binding sites based on the CCCCRRCCCC motif deduced from the two HAF binding sites. We identified a putative HAF site (CCCCTCCCCC) within a highly conserved region of CR4, known as the OCT-3/4 distal enhancer (39). Using ChIP primers flanking this region, we observe binding of HAF to CR4, which was not affected by HIF-2α knockdown, suggesting that HAF binds to CR4 in aHIF-2α independent manner (Fig. 2B iii, right panel, 2G).

To evaluate the robustness of the data, we quantitated and combined ChIP results from three independent experiments. Hence, we confirm that HAF overexpression promotes a significant increase in the binding of HIF-2α to the HREs of both VEGFA and OCT-3/4 (CR3), and that HAF itself is also recruited to the HRE in a HIF-2α dependent manner (Fig. 2C–E). Additionally, we confirm the binding of both endogenous and overexpressed HAF to the HAF site within VEGFA, and to its putative binding site within OCT-3/4 (CR4), both of which occurring independently of HIF-2α (Fig. 2F, G).

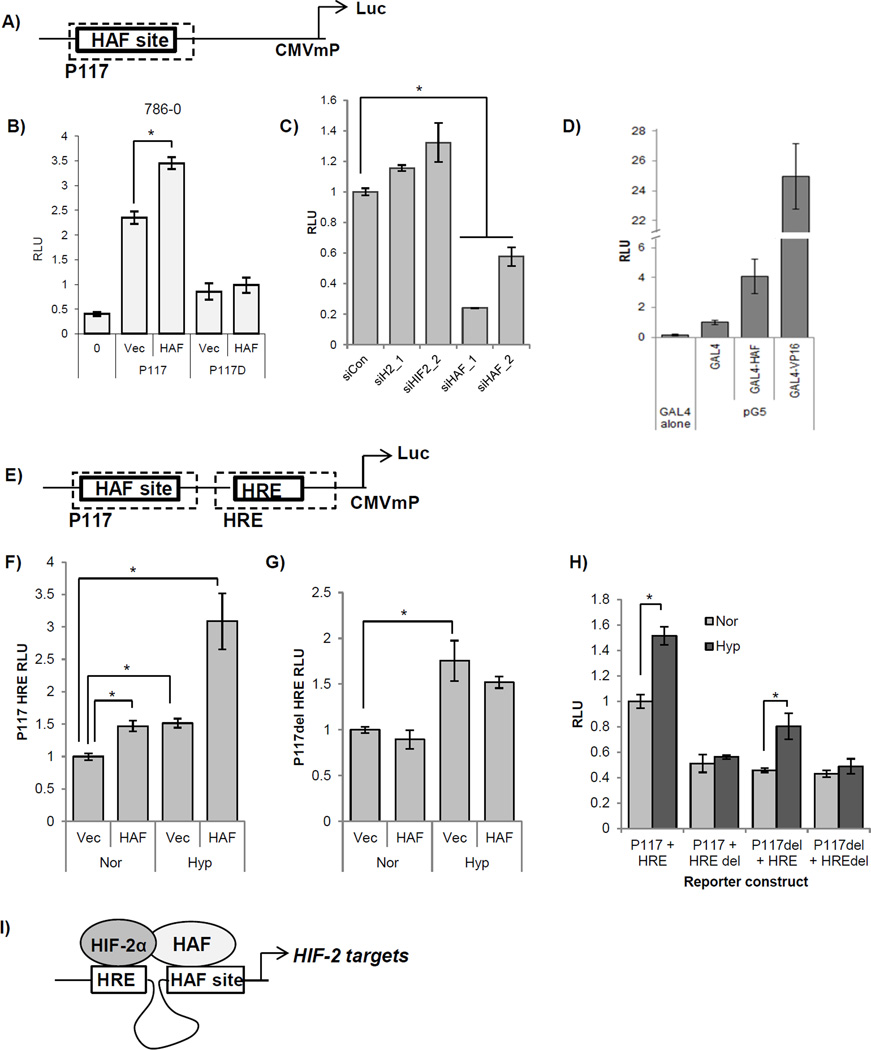

HAF binding to DNA cooperates with the HRE for maximal hypoxic induction

To determine whether HAF binding to its DNA binding site confers transcriptional activation, we used the minimal promoter of EPO, P117 (40), which contained a HAF binding site (Supplemental materials) fused to a CMV minimal promoter upstream of luciferase (P117 Luc). HAF overexpression significantly increased P117 Luc activity in 786-0, but did not affect the activity of P117del, which contained the flanking sequences of P117, and a deletion of the HAF binding sequence (CCCCCACCCCC, Fig. 3B). Similar results were obtained using PANC-1 cells (S2A). Furthermore, P117 Luc activity was significantly decreased in the presence of HAF siRNA, but was not affected by transfection with HIF-2α siRNA, suggesting that HAF binding to its site confers transcriptional activity independently of HIF-2α (Fig. 3C). Efficiency of siRNA knockdown was verified using Western blotting (S2B). To determine whether HAF on its own is sufficient to confer transcriptional activation, we used the yeast GAL4/UAS system. The GAL4 DNA-binding domain (DBD) binds a consensus UAS site on DNA, but is unable to activate transcription unless fused to a transactivator, such as the herpes simplex virus protein, VP16. When we generated a GAL4DBD-HAF fusion, we observed a significant induction of luciferase from a co-transfected 5 × UAS domain containing luciferase reporter construct, compared to transfection with the GAL4DBD alone, suggesting that HAF is sufficient to confer transcriptional activation when tethered to DNA (Fig. 3D). It should be noted that the HAF-induced increase in luciferase was substantially lower than that with GAL4-VP16, which has been described as an unusually potent transcriptional activator, possibly due to its viral origin (41).

Figure 3.

A) Schematic showing the P117 reporter construct containing the HAF site inserted upstream of a CMV minimal promoter and luciferase. B) Effects of HAF overexpression on luciferase activity of co-transfected P117 Luc or P117 containing a deletion of the HAF site (P117D), in 786-0 cells in normoxia. Results are given as relative light units (RLU) of firefly luciferase normalized to a co-transfected constitutive Renilla luciferase construct. *p<0.05. C) Effects of HAF or HIF-2α (siH2) knockdown using two different siRNA duplexes on activity of P117 in 786-0 cells in normoxia. D) Transcriptional activity of the pG5 luciferase reporter when co-transfected with the GAL4 DNA binding domain alone, GAL4 DBD-HAF fusion, or positive control GAL4 DBD-VP16. Results given as RLU of firefly luciferase normalized to Renilla encoded in the GAL4 DBD (pBIND) vector. E) Schematic showing the P117 HRE reporter construct containing the P117 sequence in tandem with the hypoxia responsive element (HRE) fused to luciferase. F–G) The effect of HAF overexpression in ACHN CRCC cells when co-transfected with F) P117 HRE Luc, or G) P117 del HRE, in normoxia and hypoxia. Results are given as relative light units (RLU) of luciferase normalized to a co-transfected constitutive Renilla luciferase construct. *p<0.05. H) Effect of deletion of the consensus HAF site or HRE site (HAF del or HRE del respectively), on the hypoxia inducibility of P117 HRE when transfected into ACHN cells and exposed to normoxia or hypoxia. Data given as RLU as in F and G, and normalized to P117HRE in normoxia. *p<0.05. I) Cartoon depicting the formation of HAF/HIF-2 transcriptional complex that promotes HIF-2 dependent transcription.

To assess the contribution of HAF and HIF binding to hypoxia-induced gene transcription, we inserted the HRE contained within the EPO enhancer in tandem with P117 Luc, to generate P117 HRE Luc (Fig. 3E). Using ACHN CRCC cells expressing wild-type pVHL for hypoxia-inducibility, we found that co-transfection of P117 HRE with HAF in normoxia, or transfection with P117 HRE alone with exposure to hypoxia, resulted in significant inductions of luciferase activity (1.5 fold each), compared to P117 HRE in normoxia (Fig. 3F). When we co-transfected P117 HRE with HAF and also exposed cells to hypoxia, we obtained a 3-fold increase in luciferase when compared to P117 HRE in normoxia, suggesting that the HAF site and the HRE both contribute to hypoxia-induced gene transcription (Fig. 3F). By contrast, co-transfection of HAF with P117del HRE (P117 HRE containing a deletion of the HAF binding sequence), did not significantly affect luciferase activity, suggesting that the binding of HAF to the HAF site is required for its transcriptional activity (Fig. 3G). To address the effects of potential non-specific activity conferred by flanking sequences, we also evaluated the transcriptional activities of constructs containing various combinations of the deletion of the HAF site (P117del), or of the HRE (HREdel). We found that deletion of the HRE but not of the HAF site abrogated the hypoxia-inducibility of P117 HRE, suggesting that the HAF site does not contribute to the hypoxia-inducibility of transcription, the latter of which is entirely dependent on the presence of the HRE (Fig. 3H).

Taken together, the results suggest that HAF, by binding to a conserved HAF DNA binding sequence within close proximity to the HRE, co-operates specifically with HIF-2α to promote HIF-2-dependent transcription (Fig. 3I).

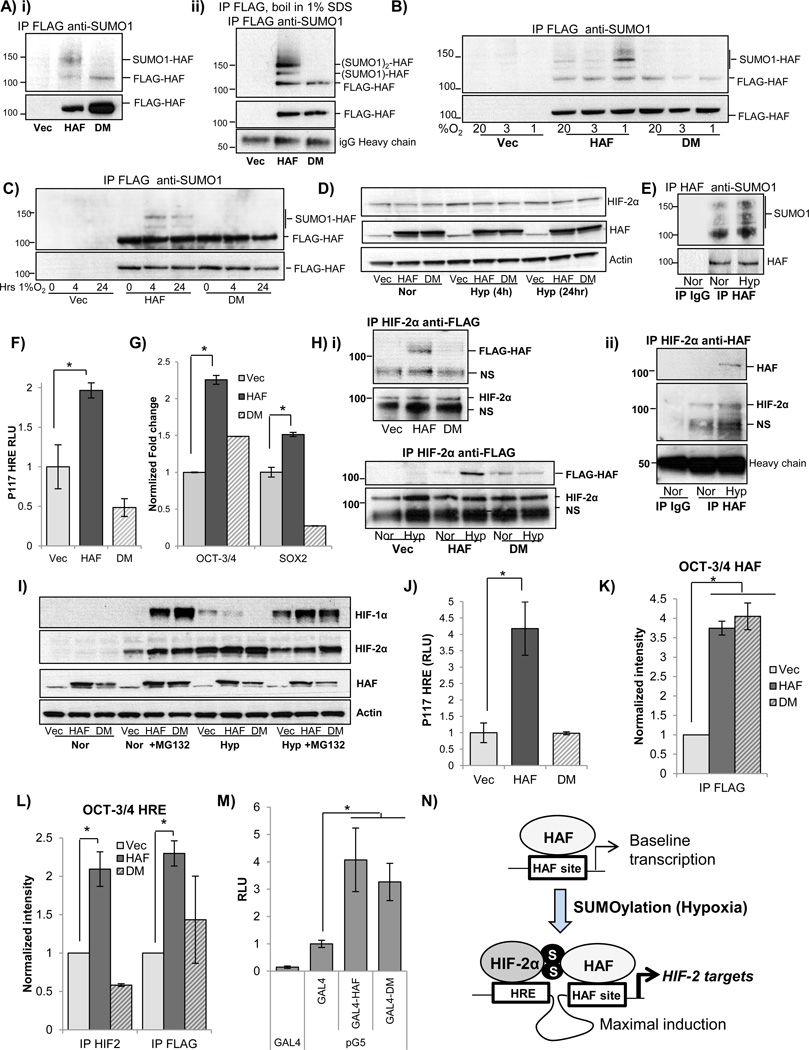

HAF SUMOylation is required for HIF-2 activation

HAF has been reported to be a target of conjugation with small ubiquitin-related modifiers (SUMO), and two SUMOylation sites (K94 and K141) have been confirmed using mass spectrometric approaches (42, 43). Protein SUMOylation and deSUMOylation can regulate a variety of diverse outcomes including changes in protein stability, localization, transcriptional activation, and protein-protein interactions (44). To determine whether the reported sites are indeed the sites of HAF SUMOylation, we overexpressed FLAG-tagged wild-type HAF (referred to as HAF), or FLAG-HAF containing lysine to arginine mutations of the residues known to be SUMOylated (K94R and K141R), referred to as HAF double mutant (DM). We observed constitutive SUMO-1 conjugation of overexpressed wild-type HAF but not of cells overexpressing HAF DM, confirming that K94R and K141R are indeed sites of HAF SUMOylation (Fig 4Ai). To confirm that the SUMOylation observed was specific for HAF, we immunoprecipitated FLAG-HAF, then boiled the samples in 1% SDS to dissociate all associated proteins, and performed a second immunoprecipitation using anti-FLAG. Indeed we found that the SUMOylated bands were retained even after denaturation, confirming that it was indeed HAF which was SUMOylated (Fig. 4A ii). Two bands were observed above the band for unmodified FLAG-HAF (120kD) with molecular weight shifts consistent with conjugation to one or two SUMO-1 molecules (each SUMO ~10kD). To determine whether HAF SUMOylation is dependent on oxygen tension, we immunoprecipitated FLAG-HAF (wt and DM) from 786-0 CRCC cells grown in normoxia (20% O2) or exposed to 3%O2, or 1%O2 for 4 hours. Oxygen tensions of 3–6% O2 and 1–3% (30–50 mm Hg; 8–15 mm Hg) are physiological in the kidney cortex and medulla respectively, whereas tensions of ≤1%O2 are typical of solid tumors (45). Intriguingly, we observed that exposure to 1% O2 resulted in a marked increase in SUMOylation (by SUMO-1) compared to exposure to 3% or 20% O2 (Fig. 4B). The increase in HAF SUMOylation was sustained, although slightly decreased after 24 hours at 1% O2, whereas levels of HAF and HIF-2α were unchanged (Fig. 4C–D). By contrast, modification by SUMO-2/3 was weak and barely detectable (S3A), and further studies hence focused exclusively on SUMO-1 modification. To determine whether SUMOylation of endogenous HAF was also hypoxia dependent, we immunoprecipitated endogenous HAF from cells grown in normoxia, or from cells exposed to 4 hours of hypoxia (1% O2). Indeed, we found that SUMOylation of endogenous HAF was also increased by hypoxia, thus supporting our findings with overexpressed HAF (Fig. 4E). To assess the impact of HAF SUMOylation on its regulation of HIF-2 activity, wild-type HAF or HAF DM was transiently transfected into 786-0 cells, together with the P117 HRE reporter. Indeed, we found that HAF DM, unlike HAF wt, was unable to induce the activity of co-transfected P117 HRE (Fig. 4F). Using quantitative RT-PCR, we confirmed that HAF DM overexpression did not promote the transcription of the HIF-2 target genes OCT-3/4 and SOX2, supporting our observations with P117 HRE (Fig. 4G). Since we have previously shown that HAF mediated HIF-2 transactivation requires HAF binding to HIF-2α (4), we examined the ability of HAF DM to bind HIF-2α. Here, we found a clear reduction in the amount of FLAG-HAF DM that could be immuno-precipitated with HIF-2α compared to that with FLAG-tagged wild type HAF (Fig. 4H i, top panel). Additionally, we observed a marked increase in the co-immunoprecipitation of FLAG-HAF (but not of HAF DM) with HIF-2α after exposure of 786-0 cells to 4 hours of hypoxia, although equal amounts of HIF-2α were immunoprecipitated, suggesting that the binding of HAF to HIF-2α is enhanced by hypoxia-dependent SUMOylation (Fig. 4H i, bottom panel). We also observed increased co-immunoprecipitation of endogenous HAF with HIF-2α in hypoxia, thus supporting our findings with overexpressed HAF (Fig. 4H ii). To investigate the impact of HAF SUMOylation in the context of functional pVHL in cells expressing both HIF-1α and HIF-2α, we also overexpressed HAF and HAF DM in PANC-1 cells. Similar to VHL-deficient cells, we observed that HAF SUMOylation in pVHL competent PANC-1 cells was also increased in hypoxia (S3B). Additionally, similar to wild-type HAF, HAF DM mediated the proteasomal-dependent degradation of HIF-1α in both normoxia and hypoxia, while not affecting levels of HIF-2α (Fig. 4I). Additionally, HAF DM expression did not induce the activity of co-transfected P117 HRE, and showed reduced binding to HIF-2α, thus confirming our findings in the 786-0 cells (Fig. 4J and S3C). Furthermore, using ChIP assays, we found that although HAF DM retained the ability to bind the HAF site within the OCT-3/4 promoter in a similar manner to wild-type HAF (Fig. 4K), HAF DM neither bound the OCT-3/4 HRE, nor promoted the binding of HIF-2α to the OCT-3/4 HRE, as observed with wild-type HAF (Fig. 4L). However, when tethered to DNA using the GAL4/UAS system, we found that GAL4-HAF DM mutant demonstrated comparable transcriptional activity to GAL4-HAF, suggesting that HAF may also possess SUMOylation independent transcriptional activity (Fig. 4M).

Figure 4.

A) i) Western blot showing immunoprecipitation of FLAG from 786-0 cell lysates overexpressing FLAG-HAF or a SUMOylation deficient mutant of HAF (FLAG-HAF DM), then probed for SUMO-1. A ii) Western blot showing effect of denaturing immunoprecipitation on HAF SUMOylation. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG, boiled in 1% SDS, and supernatant was subjected to a second IP with anti-FLAG, then probed for SUMO-1. Molecular weights consistent with unconjugated HAF or with HAF potentially conjugated with one or two SUMO-1 molecules are indicated. B) Western blot showing SUMO-1 modification of immunoprecipitated FLAG-HAF in 786-0 cells after 4 hours’ exposure to indicated oxygen tensions. C) Time course of HAF SUMOylation in response to hypoxia. Stable FLAG-HAF expressing 786-0 cells were exposed to the indicated durations of 1% O2 and analyzed as in B. D) Western blot showing levels of FLAG-HAF, FLAG-HAF DM, and HIF-2α in normoxia, and after exposure to indicated durations of hypoxia in 786-0 cells. E) Western blot showing SUMO-1 modification of endogenous HAF. Endogenous HAF was immunoprecipitated from lysates of ACHN cells after 8 hours’ hypoxia and probed with SUMO-1. F–G) Impact of transient HAF or HAF DM overexpression on, F) P117 HRE luciferase activity, or, G) transcription of HIF-2 target genes OCT-3/4 and SOX2 in 786-0 cells in normoxia determined by qRT-PCR normalized to vector control. H) i) Top panel: Western blot showing immunoprecipitation of HIF-2α from lysates of 786-0 cells (exposed to 4 hours’ hypoxia) stably expressing FLAG-HAF or FLAG-HAF DM, then probed with FLAG. Bottom panel: Western blot showing immunoprecipitation using 786-0 cell lysates as in top panel, of cells grown in normoxia or exposed to 4 hours’ hypoxia. ii) Western blot showing immunoprecipitation of HIF-2α from parental 786-0 cells in normoxia or exposed to 4 hours’ hypoxia, then probed for HAF (to detect endogenous HAF). I) Western blot showing levels of HIF-1α and HIF-2α in normoxia and hypoxia ± proteasome inhibitor, MG132 (5 µM) in PANC-1 cells stably overexpressing FLAG-HAF or FLAG-HAF DM. J) Luciferase activity in FLAG-HAF or FLAG-HAF DM overexpressing in PANC-1 cells transiently transfected with P117 HRE and normalized to Renilla luciferase. K–L) Quantitation of ChIP assays for K) CR4 (HAF site), and L) CR3 (HRE site) on the OCT-3/4 promoter. Antibodies used for ChIP are indicated below axes. *p<0.05. M) Transcriptional activity of the pG5 luciferase reporter when co-transfected with the GAL4 DNA binding domain alone, GAL4 DBD-HAF fusion, or GAL4-DBD-HAF DM mutant. Results given as RLU of firefly luciferase normalized to Renilla encoded in the GAL4 DBD (pBIND) vector. *p<0.05. N) Model for the regulation of HAF-mediated HIF-2 activation. HAF, by binding to its consensus site regulates baseline transcription of target genes. SUMOylation of HAF (which can be induced by hypoxia) promotes the binding of HAF to HIF-2α, hence driving maximal activation of HIF-2 target genes.

Hence, we show that HAF SUMOylation is required for the binding of HAF to HIF-2α, and the formation of a HAF/HIF-2α transcriptional complex that drives maximal induction of HIF-2 downstream target genes (Fig. 4N).

HAF promotes tumor metastasis in CRCC cells in vivo

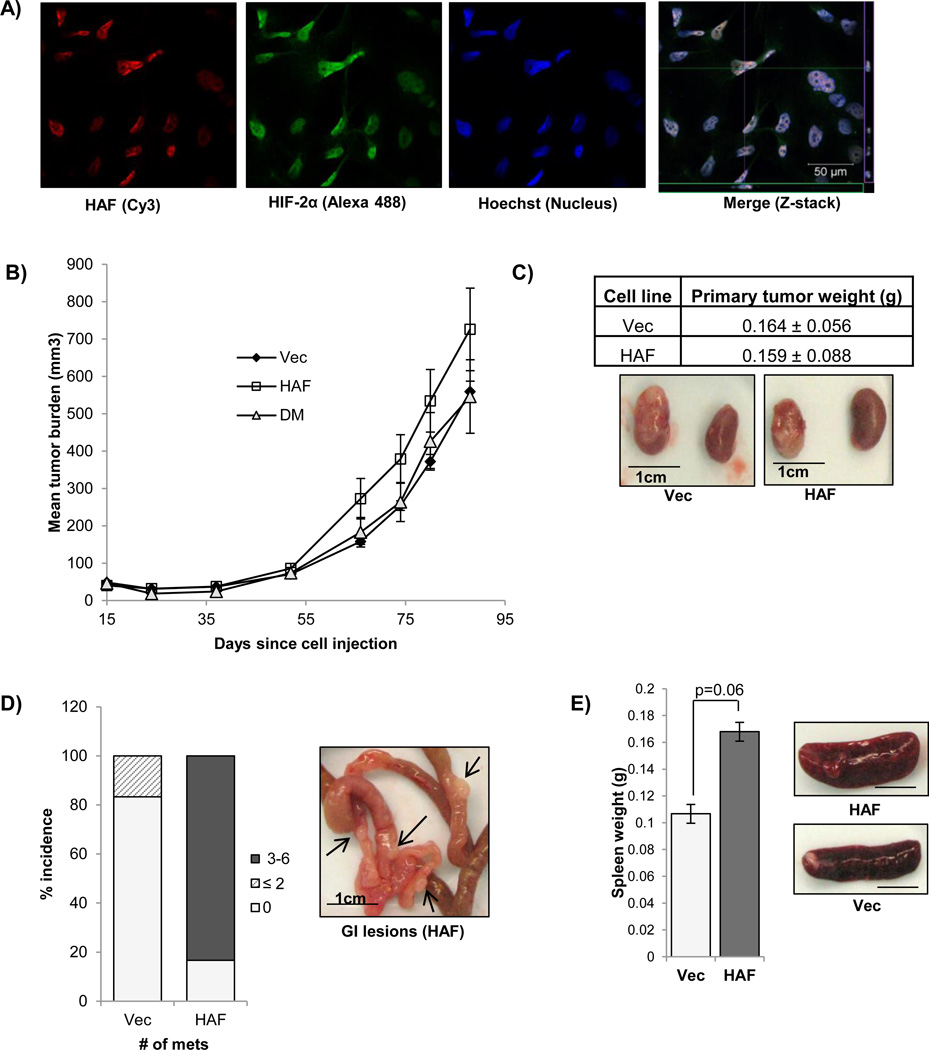

Since HIF-2α has been shown to play a unique role in driving CRCC progression, we investigated the role of HAF on tumor growth using the 786-0 CRCC cells. Using Z-stacking multispectral confocal microscopy, we confirmed that endogenous HAF (red) and HIF-2α (green) were both localized within close proximity in the nucleus of 786-0 cells (Fig. 5A). Confirmation of the specificities of the antibodies used is shown in Supplemental data (S4). When injected subcutaneously into the flanks of nude mice, we found that xenografts from cells overexpressing wild-type HAF showed a trend of increased tumor growth (p<0.1), whereas cells overexpressing HAF DM grew at a slower rate, similar to the vector control cells, consistent with our findings that SUMOylation of HAF is required for HIF-2 transactivation (Fig. 5B). The growth promoting effect mediated by HAF overexpression was only evident in vivo, as we did not observe any effects of HAF overexpression on cell proliferation in vitro (S5A). Since metastasis is frequently observed in advanced CRCC, we also investigated the impact of HAF overexpression in a 786-0 CRCC mouse renal orthotopic tumor model (46). Here we found that HAF overexpression increased the incidence and number of metastatic lesions in the GI tract of the mice (5/6 in HAF injected mice) versus 1/6 in vector injected mice (Fig. 5C–D), although there were no significant differences between the sizes of the HAF versus vector-derived primary tumors. The lesions were confirmed by the presence of GFP, encoded by the pMX vector backbone, which was not detected in the GI tract of non-tumor bearing mice, or in mice bearing vector-derived tumors (S5B). The spleen of mice bearing HAF overexpressing orthotopic tumors were also enlarged although metastatic lesions were not grossly apparent (Fig. 5E). Hence, HAF overexpression in vivo promotes the growth of subcutaneous tumor xenografts, and in a kidney orthotopic model, results in increased metastasis.

Figure 5.

A) Confocal immunocytochemistry showing localization of endogenous HAF and HIF-2α to the nucleus of 786-0 CRCC cells (40× magnification). Merge image shows representative slice of the Z-stack whereas green and purple boxes (on the x and y-axes) indicate axial views of the 0.8–1.0 µM slice. B) In vivo tumor growth of 786-0 HAF and 786-0 HAF DM cells compared to vector control when grown as subcutaneous xenografts in nude mice (10 per group). C) Comparison of primary tumor weights obtained with orthotopic implantation of HAF or vector 786-0 cells into the renal subcapsule of nude mice (± SE). Representative photographs of injected and control kidneys are shown. D) Percentage incidence and number of metastases observed in GI tracts of mice injected with HAF or vector 786-0 cells. Representative photograph of metastases are shown inset. E) Average spleen weights and representative photographs of spleens in the mice injected with the HAF or vector overexpressing cells.

HAF is associated with decreased PFS in CRCC

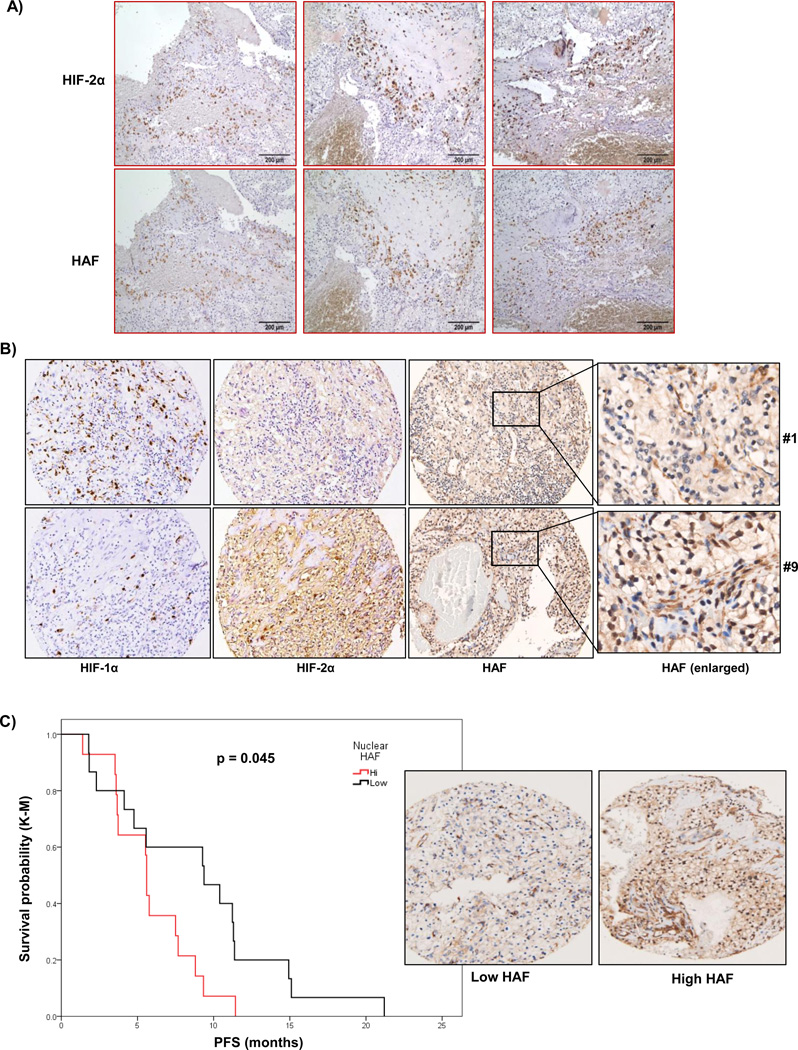

To investigate the clinical application of our findings, we examined HAF and HIF-2α distribution in patient CRCC tissue. When we stained serial sections of tumor tissue obtained from human stage III CRCC, we observed that regions of the tumor that expressed high levels of HIF-2α also expressed high levels of HAF (Fig. 6A). This suggests that the HAF/HIF-2α complex may also be present in vivo to promote HIF-2 dependent transcription. To investigate the relationship between HAF and CRCC patient prognosis, we stained a tumor microarray (TMA) from patients with stage III/IV advanced metastatic CRCC (33). Staining intensities for HAF, HIF-1α and HIF-2α together with other clinical parameters are shown in S6A. Representative sections of high and low HIF-1/2α expressing cores with nuclear and cytoplasmic HAF expression are depicted in Fig. 6B. Overall, we found that HIF-1α staining was almost exclusively nuclear, whereas HIF-2α staining was both nuclear and cytoplasmic. HAF staining was also both nuclear and cytoplasmic, and there was a significant correlation between cytoplasmic and nuclear HAF expression (S6B). When we divided the patients into two groups according to the levels of nuclear HAF, we observed a significant correlation between patients with high HAF and decreased progression-free survival (PFS), a surrogate endpoint for survival (p = 0.045; Fig. 6C). The hazard ratio for high HAF and time to progression was 2.263 (95% CI; 1.001–5.116). The median PFS for patients with high versus low HAF was 5.94 ± 0.62 versus 8.97 ± 3.1 months and approached significance (p=0.08). The only other univariate parameter that also showed significant association with PFS was Motzer criteria (47), with a hazard ratio of 2.34 (95% CI; 0.9985–5.492) for intermediate versus good criteria, and time to progression (S7). Other parameters such as age, sex and number of disease sites were not significantly associated with PFS (not shown). Additionally, we did not detect any significant correlations between levels of HIF-1α or HIF-2α and PFS (S8). Hence nuclear HAF may be a novel predictor of poor patient response in high grade CRCC.

Figure 6.

A) Localization of HAF and HIF-2α in sequential sections of human Grade III CRCC (10× magnification). B) Representative photomicrographs showing expression of HIF-1α, HIF-2α and HAF in CRCC tissue cores from two different patients. Enlarged sections show differences in nuclear localization of HAF. C) Kaplan-Meier plot representing the probability of progression-free survival in CRCC patients, stratified according to high or low nuclear HAF expression levels. Representative images of low and high HAF expressing samples are shown inset.

Discussion

We have previously shown that HAF promotes the switch from HIF-1 to HIF-2 dependent transcription in variety of cancer cell lines (4). HAF is an E3 ubiquitin ligase that promotes the ubiquitination and degradation of HIF-1(6). HAF also binds to HIF-2 but does not promote degradation, but rather increases HIF-2 transactivation. Here we show that HAF-mediated HIF-2 transactivation requires both the binding of HAF to its DNA consensus site, and the hypoxia-dependent SUMOylation of HAF, which promotes its interaction with HIF-2α. Hence SUMOylated HAF contributes to the maximal induction of HIF-2 target genes, and this is particularly clear in the pluripotency genes OCT-3/4, SOX2 and NANOG. The fact that this subset of HIF-2 dependent genes retains hypoxia inducibility despite loss of VHL (Fig. 1D) supports the existence of an alternative oxygen sensing mechanism such as HAF SUMOylation, which may play a role in the progression of VHL-deficient CRCC.

We have observed that the HAF mutant that cannot be SUMOylated appears to be more efficient at degrading HIF-1α than wild-type HAF (Fig. 4I). This suggests that HAF SUMOylation is a determinant of its HIF-α isoform selectivity. In this regard, HAF binds and ubiquitinates HIF-1α through the HAF E3 ligase domain located at the HAF C-terminus, and this occurs independently of HAF SUMOylation. By contrast, HAF SUMOylation, which occurs at the HAF N-terminal region, close to the HIF-2α binding domain (HAF 300–500), facilitates the binding of HAF to HIF-2α, thus promoting HIF-2 dependent transcription. In this regard, decreased HAF SUMOylation may reduce binding to HIF-2α thus increasing the amount of available HAF to bind and degrade HIF-1α, resulting in the increased HIF-1α degradation. Alternatively, it is also possible that HAF SUMOylation may interfere with its E3 ubiquitin ligase activity. Whichever the case may be, modulators of HAF SUMOylation may dictate whether it acts primarily as an activator of HIF-2α, or as an inhibitor of HIF-1α.

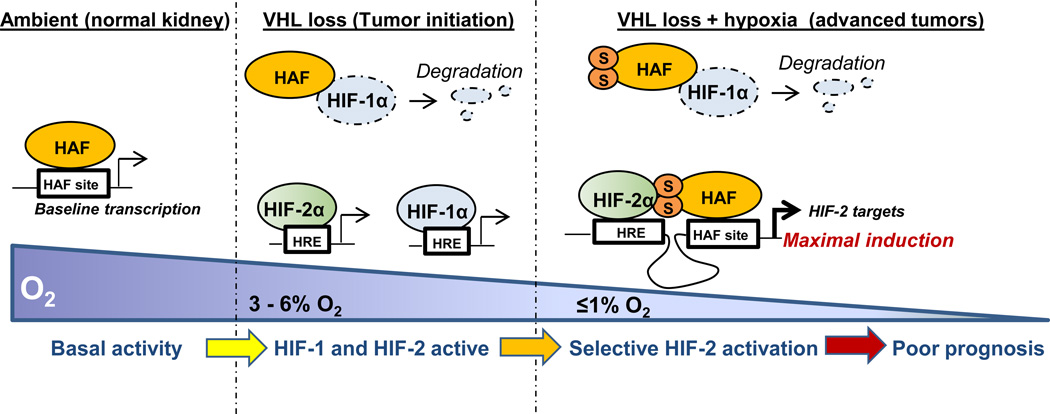

Based on our findings, we propose that under ambient conditions, when HIF-1/2α are largely absent, HAF drives baseline transcription by binding the HAF site within the promoters of target genes. As the HAF site within the OCT-3/4 promoter resides within the distal enhancer, which is required for OCT-3/4 transcription in embryonic stem cells, HAF may also be an important regulator of OCT-3/4 transcription in these cells (39). During VHL loss (CRCC tumor initiation), both HIF-1α and HIF-2α are stabilized and activate downstream transcription. Under these conditions, HAF functions as an E3 ligase for HIF-1α, hence attenuating the increase in HIF-1α caused by pVHL loss. As CRCC tumors develop and begin to experience regions of hypoxia, HAF becomes SUMOylated and is able to bind and transactivate HIF-2, driving maximal induction of HIF-2 target genes (particularly of the HIF-2 dependent pluripotency genes OCT-3/4, SOX2 and NANOG), while continuing to degrade HIF-1α. Thus, the combination of the non-hypoxic constitutive activation of the HIFs (pseudohypoxia) manifest during pVHL loss, and the presence of SUMOylated HAF in hypoxic CRCC tumors, promote preferential activation of HIF-2α, thus mediating the shift to HIF-2 dependent transcription frequently observed in pVHL-deficient CRCC (Fig. 7). By contrast, differences in hypoxia-dependent spatiotemporal stabilization of HIF-1α versus HIF-2α may limit the extent of HAF-mediated HIF-2 specific activation due to fluctuations in HIF-2α availability in other solid tumor types not associated with VHL-loss (2).

Figure 7.

Proposed mechanism for HAF mediated HIF-α isoform specific regulation. Under ambient conditions, HAF is deSUMOylated and drives baseline transcription of target genes, where as both HIF-1α and HIF-2α are absent. During tumor initiation, VHL loss results in the constitutive activation of both HIF-1α and HIF-2α, and HAF functions as an E3 ligase for HIF-1α. Oxygen becomes limiting as tumors become established, resulting in HAF SUMOylation. This promotes HAF binding to HIF-2α, driving maximal activation of HIF-2 target genes. At the same time, HAF still binds and degrades HIF-1α independently of SUMOylation, effectively inhibiting HIF-1α, and promoting that activation of HIF-2 target genes in CRCC.

Hypoxia-dependent SUMOylation has increasingly been shown to regulate the hypoxia response. PIASy, a SUMO E3 ligase upregulated in hypoxia, SUMOylates pVHL, resulting in pVHL oligomerization, abolishing its ability to degrade HIF-1α (48). Hypoxia-dependent SUMOylation of HIF-1/2α has also been reported, and this promotes HIF-1/2α degradation by pVHL, although this is typically reversed by the SUMO specific protease 1 (SENP1) (49, 50). Conversely, SUMOylation of HIF-1α can also promote HIF-1α stabilization and transcriptional activity (51). Hence, SUMOylation and deSUMOylation have clear consequences on the HIF pathway, and their physiological (and pathophysiological) significance remain to be elucidated. We have not yet identified the SUMO E3 ligase responsible for the hypoxia-dependent SUMOylation of HAF. However, to our knowledge, the hypoxia-dependent SUMOylation of HAF is the first report of SUMO-mediated HIF-α isoform-specific regulation.

In human patients, increased HAF levels correlate to decreased PFS in patients with metastatic Grade III/IV CRCC. Indeed, the only other univariate parameter that also showed significant association with PFS was Motzer criteria, a classification system for advanced RCC that has shown excellent predictive value, and which has been used to select and stratify patients for treatment (47, 52). We did not detect any significant correlations between levels of HIF-1α or HIF-2α and PFS (S8). This may be due to the advanced stage of the tumors used in our study, compared to previously reported relationships between the HIFs and patient survival, which were identified in samples comprising multiple tumor stages (15, 26, 53).

In summary, we have identified a novel mechanism determining the HIF-α isoform specificity of HAF. Hypoxia-dependent SUMOylation of HAF enables its binding to HIF-2α to promote the transcription of HIF-2 target genes without affecting HAFs ability to bind and degrade HIF-1α. In the context of the pVHL deficiency frequently observed in CRCC, this may result in preferential HIF-2 specific activation that drives tumor progression resulting in poor patient prognosis. Hence, the targeting of the HAF/HIF-2 axis offersa promising therapeutic strategy for the treatment of CRCC.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grant CA181106 (MYK), ASCO Young Investigator Award-Kidney Cancer Association (THH), NIH grant CA098920 (GP). The work was also supported by the Cancer Center Support Grant NIH CA030199.

Footnotes

Author contributions

MYK generated the hypothesis upon which the paper is based, designed and performed the experiments, interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. BGD and VN generated constructs and made stable cell lines. RL performed animal experiments. GK performed IHC and ICC. JAK, EJ and THH provided patient tissue and data, and assisted with analysis. FAM provided pathology support. GP conceived the project, assisted with experimental design and interpretation, and participated in the writing of the manuscript.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Wilson WR, Hay MP. Targeting hypoxia in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:393–410. doi: 10.1038/nrc3064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koh MY, Powis G. Passing the baton: the HIF switch. Trends Biochem Sci. 2012;37:364–372. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holmquist-Mengelbier L, Fredlund E, Lofstedt T, Noguera R, Navarro S, Nilsson H, et al. Recruitment of HIF-1alpha and HIF-2alpha to common target genes is differentially regulated in neuroblastoma: HIF-2alpha promotes an aggressive phenotype. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:413–423. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koh MY, Lemos R, Jr, Liu X, Powis G. The Hypoxia-Associated Factor Switches Cells from HIF-1{alpha}- to HIF-2{alpha}-Dependent Signaling Promoting Stem Cell Characteristics, Aggressive Tumor Growth and Invasion. Cancer Res. 2011;71:4015–4027. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keith B, Johnson RS, Simon MC. HIF1alpha and HIF2alpha: sibling rivalry in hypoxic tumour growth and progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:9–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc3183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koh MY, Darnay BG, Powis G. Hypoxia-associated factor, a novel E3-ubiquitin ligase, binds and ubiquitinates hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha, leading to its oxygen-independent degradation. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:7081–7095. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00773-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gnarra JR, Tory K, Weng Y, Schmidt L, Wei MH, Li H, et al. Mutations of the VHL tumour suppressor gene in renal carcinoma. Nat Genet. 1994;7:85–90. doi: 10.1038/ng0594-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moore LE, Nickerson ML, Brennan P, Toro JR, Jaeger E, Rinsky J, et al. Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) inactivation in sporadic clear cell renal cancer: associations with germline VHL polymorphisms and etiologic risk factors. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002312. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Banks RE, Tirukonda P, Taylor C, Hornigold N, Astuti D, Cohen D, et al. Genetic and epigenetic analysis of von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) gene alterations and relationship with clinical variables in sporadic renal cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2000–2011. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang GL, Jiang BH, Rue EA, Semenza GL. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 is a basic-helix-loop-helix-PAS heterodimer regulated by cellular O2 tension. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:5510–5514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baldewijns MM, van Vlodrop IJ, Vermeulen PB, Soetekouw PM, van Engeland M, de Bruine AP. VHL and HIF signalling in renal cell carcinogenesis. J Pathol. 2010;221:125–138. doi: 10.1002/path.2689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Welford SM, Dorie MJ, Li X, Haase VH, Giaccia AJ. Renal oxygenation suppresses VHL loss-induced senescence that is caused by increased sensitivity to oxidative stress. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:4595–4603. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01618-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bratslavsky G, Sudarshan S, Neckers L, Linehan WM. Pseudohypoxic Pathways in Renal Cell Carcinoma. Clinical Cancer Research. 2007;13:4667–4671. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen Y, Zhang J, Dai J, Feng X, Lu H, Zhou C. Angiogenesis of renal cell carcinoma: perfusion CT findings. Abdom Imaging. 2010;35:622–628. doi: 10.1007/s00261-009-9565-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mandriota SJ, Turner KJ, Davies DR, Murray PG, Morgan NV, Sowter HM, et al. HIF activation identifies early lesions in VHL kidneys: evidence for site-specific tumor suppressor function in the nephron. Cancer Cell. 2002;1:459–468. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00071-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schietke RE, Hackenbeck T, Tran M, Gunther R, Klanke B, Warnecke CL, et al. Renal tubular HIF-2alpha expression requires VHL inactivation and causes fibrosis and cysts. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31034. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turner KJ, Moore JW, Jones A, Taylor CF, Cuthbert-Heavens D, Han C, et al. Expression of hypoxia-inducible factors in human renal cancer: Relationship to angiogenesis and to the von Hippel-Lindau gene mutation. Cancer Research. 2002;62:2957–2961. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gordan JD, Lal P, Dondeti VR, Letrero R, Parekh KN, Oquendo CE, et al. HIF-alpha effects on c-Myc distinguish two subtypes of sporadic VHL-deficient clear cell renal carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2008;14:435–446. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kondo K, Kim WY, Lechpammer M, Kaelin WG., Jr Inhibition of HIF2alpha is sufficient to suppress pVHL-defective tumor growth. PLoS Biol. 2003;1:E83. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0000083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maranchie JK, Vasselli JR, Riss J, Bonifacino JS, Linehan WM, Klausner RD. The contribution of VHL substrate binding and HIF1-α to the phenotype of VHL loss in renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2002;1:247–255. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raval RR, Lau KW, Tran MG, Sowter HM, Mandriota SJ, Li JL, et al. Contrasting properties of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) and HIF-2 in von Hippel-Lindau-associated renal cell carcinoma. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:5675–5686. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.13.5675-5686.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zimmer M, Doucette D, Siddiqui N, Iliopoulos O. Inhibition of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor Is Sufficient for Growth Suppression of VHL−/− Tumors1 1 NIH grant R29CA78358-06 (O. I.), Bertucci Fund for Urologic Malignancies (O. I.), David P. Foss Fund (O. I.), and VHL Family Alliance 2003 award (M. Z.) Molecular Cancer Research. 2004;2:89–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li L, Zhang L, Zhang X, Yan Q, Minamishima YA, Olumi AF, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor linked to differential kidney cancer risk seen with type 2A and type 2B VHL mutations. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:5381–5392. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00282-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hacker KE, Lee CM, Rathmell WK. VHL type 2B mutations retain VBC complex form and function. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3801. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shen C, Beroukhim R, Schumacher S, Zhou J, Chang M, Signoretti S, et al. Genetic and Functional Studies Implicate HIF1α as a 14q Kidney Cancer Suppressor Gene. Cancer Discovery. 2011 doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Monzon FA, Alvarez K, Peterson L, Truong L, Amato RJ, Hernandez-McClain J, et al. Chromosome 14q loss defines a molecular subtype of clear-cell renal cell carcinoma associated with poor prognosis. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:1470–1479. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2011.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lamothe B, Besse A, Campos AD, Webster WK, Wu H, Darnay BG. Site-specific Lys-63-linked tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated Factor 6 auto-ubiquitination is a critical determinant of IkappaB kinase activation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:4102–4112. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609503200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blanchard KL, Acquaviva AM, Galson DL, Bunn HF. Hypoxic induction of the human erythropoietin gene: cooperation between the promoter and enhancer, each of which contains steroid receptor response elements. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:5373–5385. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.12.5373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kimura H, Weisz A, Ogura T, Hitomi Y, Kurashima Y, Hashimoto K, et al. Identification of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 ancillary sequence and its function in vascular endothelial growth factor gene induction by hypoxia and nitric oxide. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:2292–2298. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008398200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Polek TC, Talpaz M, Darnay BG, Spivak-Kroizman T. TWEAK mediates signal transduction and differentiation of RAW264.7 cells in the absence of Fn14/TweakR. Evidence for a second TWEAK receptor. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:32317–32323. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302518200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paine-Murrieta GD, Taylor CW, Curtis RA, Lopez MH, Dorr RT, Johnson CS, et al. Human tumor models in the severe combined immune deficient (scid) mouse. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1997;40:209–214. doi: 10.1007/s002800050648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang L, Zhang X, Barrisford GW, Olumi AF. Lexatumumab (TRAIL-receptor 2 mAb) induces expression of DR5 and promotes apoptosis in primary and metastatic renal cell carcinoma in a mouse orthotopic model. Cancer Letters. 2007;251:146–157. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jonasch E, Corn P, Pagliaro LC, Warneke CL, Johnson MM, Tamboli P, et al. Upfront, randomized, phase 2 trial of sorafenib versus sorafenib and low-dose interferon alfa in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma: clinical and biomarker analysis. Cancer. 2010;116:57–65. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shen C, Beroukhim R, Schumacher SE, Zhou J, Chang M, Signoretti S, et al. Genetic and functional studies implicate HIF1alpha as a 14q kidney cancer suppressor gene. Cancer Discov. 2011;1:222–235. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gupta M, Mungai PT, Goldwasser E. A new transacting factor that modulates hypoxia-induced expression of the erythropoietin gene. Blood. 2000;96:491–497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nordhoff V, Hubner K, Bauer A, Orlova I, Malapetsa A, Scholer HR. Comparative analysis of human, bovine, and murine Oct-4 upstream promoter sequences. Mamm Genome. 2001;12:309–317. doi: 10.1007/s003350010279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Covello KL, Kehler J, Yu H, Gordan JD, Arsham AM, Hu CJ, et al. HIF-2alpha regulates Oct-4: effects of hypoxia on stem cell function, embryonic development, and tumor growth. Genes Dev. 2006;20:557–570. doi: 10.1101/gad.1399906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Warnecke C, Zaborowska Z, Kurreck J, Erdmann VA, Frei U, Wiesener M, et al. Differentiating the functional role of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1alpha and HIF-2alpha (EPAS-1) by the use of RNA interference: erythropoietin is a HIF-2alpha target gene in Hep3B and Kelly cells. Faseb J. 2004;18:1462–1464. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1640fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yeom YI, Fuhrmann G, Ovitt CE, Brehm A, Ohbo K, Gross M, et al. Germline regulatory element of Oct-4 specific for the totipotent cycle of embryonal cells. Development. 1996;122:881–894. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.3.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blanchard KL, Acquaviva AM, Galson DL, Bunn HF. Hypoxic induction of the human erythropoietin gene: cooperation between the promoter and enhancer, each of which contains steroid receptor response elements. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:5373–5385. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.12.5373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sadowski I, Ma J, Triezenberg S, Ptashne M. GAL4-VP16 is an unusually potent transcriptional activator. Nature. 1988;335:563–564. doi: 10.1038/335563a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schimmel J, Balog CI, Deelder AM, Drijfhout JW, Hensbergen PJ, Vertegaal AC. Positively charged amino acids flanking a sumoylation consensus tetramer on the 110kDa tri-snRNP component SART1 enhance sumoylation efficiency. J Proteomics. 2010;73:1523–1534. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vertegaal AC, Ogg SC, Jaffray E, Rodriguez MS, Hay RT, Andersen JS, et al. A proteomic study of SUMO-2 target proteins. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:33791–33798. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404201200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Geiss-Friedlander R, Melchior F. Concepts in sumoylation: a decade on. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:947–956. doi: 10.1038/nrm2293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nangaku M, Eckardt KU. Hypoxia and the HIF system in kidney disease. Journal of molecular medicine. 2007;85:1325–1330. doi: 10.1007/s00109-007-0278-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Naito S, von Eschenbach AC, Fidler IJ. Different growth pattern and biologic behavior of human renal cell carcinoma implanted into different organs of nude mice. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1987;78:377–385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Motzer RJ, Bacik J, Schwartz LH, Reuter V, Russo P, Marion S, et al. Prognostic factors for survival in previously treated patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:454–463. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cai Q, Verma SC, Kumar P, Ma M, Robertson ES. Hypoxia inactivates the VHL tumor suppressor through PIASy-mediated SUMO modification. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9720. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cheng J, Kang X, Zhang S, Yeh ET. SUMO-specific protease 1 is essential for stabilization of HIF1alpha during hypoxia. Cell. 2007;131:584–595. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.van Hagen M, Overmeer RM, Abolvardi SS, Vertegaal AC. RNF4 and VHL regulate the proteasomal degradation of SUMO-conjugated Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-2alpha. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:1922–1931. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carbia-Nagashima A, Gerez J, Perez-Castro C, Paez-Pereda M, Silberstein S, Stalla GK, et al. RSUME, a Small RWD-Containing Protein, Enhances SUMO Conjugation and Stabilizes HIF-1α during Hypoxia. Cell. 2007;131:309–323. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dorff TB, Goldkorn A, Quinn DI. Review: Targeted therapy in renal cancer. Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology. 2009;1:183–205. doi: 10.1177/1758834009349119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sandlund J, Ljungberg B, Wikstrom P, Grankvist K, Lindh G, Rasmuson T. Hypoxia-inducible factor-2alpha mRNA expression in human renal cell carcinoma. Acta Oncol. 2009;48:909–914. doi: 10.1080/02841860902824891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.