Abstract

Background

Current neonatal resuscitation guidelines recommend tracheal suctioning of non-vigorous neonates born through meconium stained amniotic fluid.

Methods

We evaluated the effect of tracheal suctioning at birth in 29 lambs with asphyxia induced by cord occlusion and meconium aspiration during gasping.

Results

Tracheal suctioning at birth (n=15) decreased amount of meconium in distal airways (53±29 particles/mm2 lung area) compared to no-suction (499±109 particles/mm2, n=14, p<0.001). Three lambs in the suction group had cardiac arrest during suctioning requiring chest compressions and epinephrine. Onset of ventilation was delayed in the suction group (146±11 vs. 47±3 sec in no-suction group, p=0.005). There was no difference in pulmonary blood flow, carotid blood flow, pulmonary or systemic blood pressure between the two groups. Left atrial pressure was significantly higher in the suction group. Tracheal suctioning resulted in higher PaO2/FiO2 levels (122±21 vs. 78±10 mmHg) and ventilator efficiency index (0.3±0.05 vs.0.16±0.03). Two lambs in the no-suction group required inhaled NO. Lung 3-nitrotyrosine levels were higher in the suction group (0.65±0.03 ng/μg protein) compared to the no-suction group (0.47 ± 0.06).

Conclusion

Tracheal suctioning improves oxygenation and ventilation. Suctioning does not improve pulmonary/systemic hemodynamics or oxidative stress in an ovine model of acute meconium aspiration with asphyxia.

Introduction

The significance and perinatal management of meconium stained amniotic fluid (MSAF) has evolved over time. Routine amnioinfusion and tracheal suctioning(1-4) were considered to reduce the incidence of meconium aspiration syndrome (MAS) by diluting meconium consistency, decreasing cord compression and removing meconium(5). Large, multicenter, randomized trials concluded that amnioinfusion or tracheal suctioning in vigorous infants did not alter the incidence of MAS(6-8).

The Neonatal Resuscitation Program (NRP) protocol for delivery room management no longer recommends tracheal suctioning for vigorous infants(9). Approximately 20-30% of infants born through MSAF are depressed at birth with an Apgar score of 6 or less at 1 minute of age(10). Babies exposed to MSAF who have respiratory depression at birth have a higher incidence of MAS(11). If a baby is born through MSAF, has depressed respirations, decreased muscle tone, and/or a heart rate below 100/min, intubation and direct suctioning of the trachea soon after delivery is indicated before breaths have occurred. There are no randomized, clinical or translational studies evaluating the effect of tracheal suctioning on hemodynamics and gas exchange with perinatal meconium aspiration and asphyxia induced depression.

We conducted a randomized study in a lamb model of prenatal asphyxia induced depression associated with “spontaneous” meconium aspiration during gasping. We hypothesized that tracheal suctioning in lambs with asphyxia induced depression at birth with MSAF will reduce the severity of hypoxic respiratory failure (HRF), reduce pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR), improve oxygenation and ventilation compared to lambs that receive positive pressure ventilation (PPV) without suctioning. We quantified the amount of meconium suctioned and the distribution of meconium in the lung using fluorescent microspheres. We further hypothesized that tracheal suctioning, secondary to improved oxygenation and reduced FiO2, will decrease markers of oxidative stress (lung 3-nitrotyrosine and superoxide) in the lung.

Results

Twenty nine lambs were randomized, delivered and instrumented. Baseline characteristics, lung liquid drained and volume of meconium aspirated were similar in both groups (table 1). Three lambs with asphyxia induced bradycardia had cardiac arrest when trachea was suctioned for meconium. Two lambs were successfully resuscitated with chest compressions and one dose of intravenous epinephrine and one lamb died. The incidence of cardiac arrest in the suction group (3/15) was not different from no-suction group (0/14, p=0.22 by Fisher's exact test). Two lambs in the no-suction group required inhaled NO to maintain oxygenation. As epinephrine and inhaled NO significantly altered physiological parameters, these 5 lambs were excluded from analysis of hemodynamics and gas exchange data.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics (mean ± SEM or %).

| No suction (n=14) | Suction (n=15) | |

|---|---|---|

| Birth weight (grams) | 2863 ± 174 | 3091 ± 235 |

| Gestational age (days) | 139.2 ± 0.9 | 139.3 ± 1.1 |

| Gender (% male) | 7 (50%) | 7 (46%) |

| Multiplicity Single: Twin | 6:8 | 6:9 |

| Fetal lung liquid drained prior to meconium instillation (ml) | 44 ± 7 | 41 ± 5 |

| Aspirated volume of meconium ml/kg | 5.2 ± 0.3 | 5.1 ± 0.3 |

| Total number of gasps prior to delivery (resulting in meconium aspiration) | 12 ± 2 | 14 ± 2 |

| Arterial pH baseline (prior to cord occlusion) | 7.29 ± 0.02 | 7.29 ± 0.02 |

| Arterial pH after asphyxia prior to delivery | 6.98 ± 0.02 | 6.98 ± 0.05 |

Removal of meconium by suction

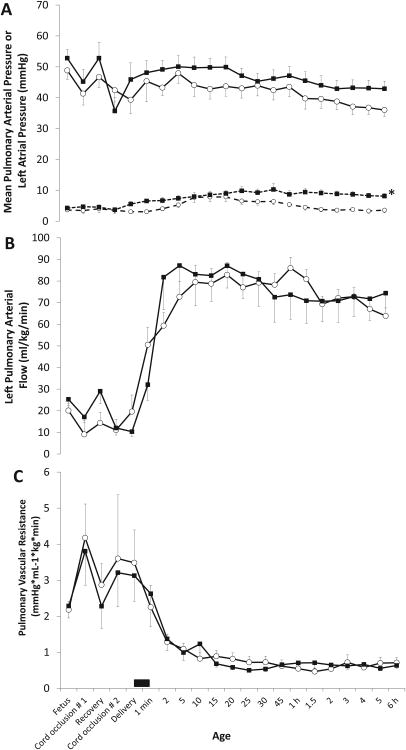

The time from onset of first cord clamp to initiation of resuscitation with PPV was similar (20.2 ± 1 in no-suction and 23.7 ± 3 min in suction group). The time from birth (cutting the umbilical cord) to onset of PPV (including the time to reintubate with a fresh endotracheal tube in both groups) was significantly delayed in the suction group (47 ± 3 sec in no-suction and 146 ± 11 sec in the suction group, p < 0.001). Tracheal suctioning at birth led to removal of 60 ± 6% of instilled meconium as quantified by fluorescence (table 2). Subsequent airway lavage after 6 hours of ventilation recovered more meconium in the no-suction group compared to the suction group. Fluorescent microscopic examination of the right middle lobe (tied off during lavage) showed significantly less fluorescent particles in the lung compared to the no-suction group (figure 1).

Table 2. Effect of suctioning on distribution of fluorescent beads (meconium) in lambs.

| Measurement of Fluorescence | No Suction (n=14) | Suction (n=15) |

|---|---|---|

| Direct suction at birth | n/a | 60±6% instilled meconium |

| Lung (except right “middle” lobe) lavage after 6h of ventilation | 14±5% of instilled fluorescence | 7±1.6% of instilled fluorescence |

| Right middle lobe fluorescent particle density | 499±109 particles/unit area of lung | 53±29* particles/unit area of lung |

p = 0.005 compared to no-suction group

Figure 1.

Distribution of meconium and 3-nitrotyrosine: Fluorescent imaging of a section the right lung (middle lobe) after 6 hours of ventilation from A. Suction group and B. No-suction group. The pink fluorescent beads (arrows) represent meconium and green fluorescence shows 3-nitrotyrosine staining. Magnification scale - 500μM.

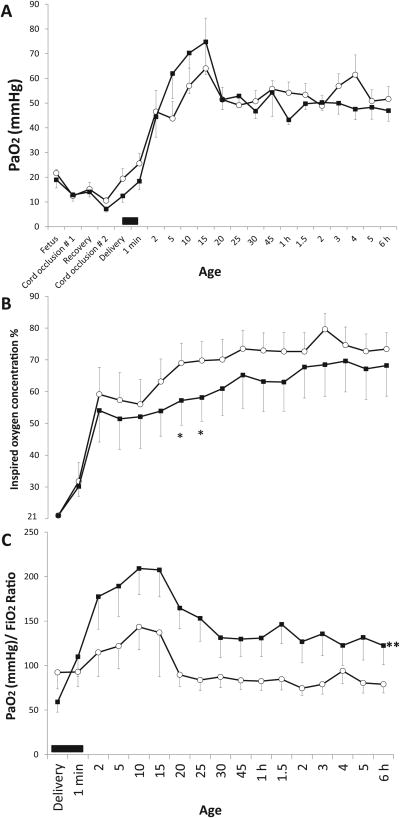

Oxygenation

Baseline fetal oxygenation was similar in both groups of lambs (PaO2 21.6 ± 1.6 vs. 19 ± 3.3 mmHg in no suction and suction groups respectively) and significantly decreased following cord occlusion (10.5 ± 1.3 in the no suction group and 8.6 ± 3.9 mmHg in the suction group, figure 2A). Oxygenation improved in both groups with resuscitation and PPV. Inspired oxygen was set at 21% initially and increased as per current NRP guidelines(12). Inspired oxygen required to maintain preductal SpO2 between 90-95% was lower in the suction group (figure 2B). Oxygenation is depicted as PaO2 / FiO2 ratio after onset of PPV in figure 2C and was significantly higher in the suction group.

Figure 2.

Oxygenation: Mean ± SEM from asphyxiated lambs with meconium aspiration and tracheal suction at birth (n=12, shown in black squares) and no-suction (n=12, open circles). Right carotid arterial PaO2 (panel A), inspired oxygen (panel B) and PaO2/FiO2 ratio (panel C) are shown. The values during fetal and postnatal period are shown in panel A. Postnatal values are shown in panels B and C. The black bar on the X-axis depicts the period of tracheal suctioning. (* p < 0.05 by ANOVA compared to no-suction group at the specified time point; ** p < 0.05 compared to no-suction by ANOVA repeated measures for the postnatal period).

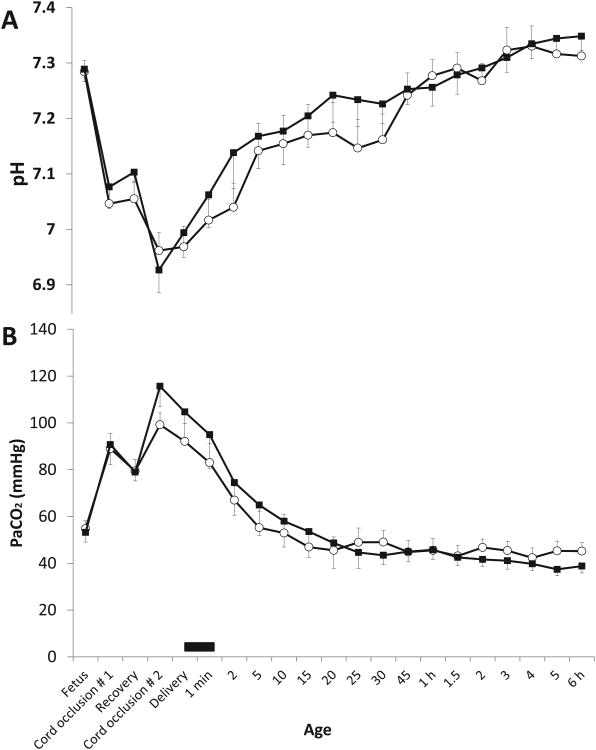

Arterial pH

Baseline arterial pH was similar in both groups (table 1 and figure 3A). Cord occlusion resulted in significant acidosis. Arterial pH improved with ventilation and was similar in both groups.

Figure 3.

Arterial pH (panel A) and PCO2 (Panel B): Mean ± SEM from asphyxiated lambs with meconium aspiration with tracheal suction at birth (n=12, shown in black squares) and no-suction (n=12, open circles). The black bar on the X-axis depicts the period of tracheal suctioning.

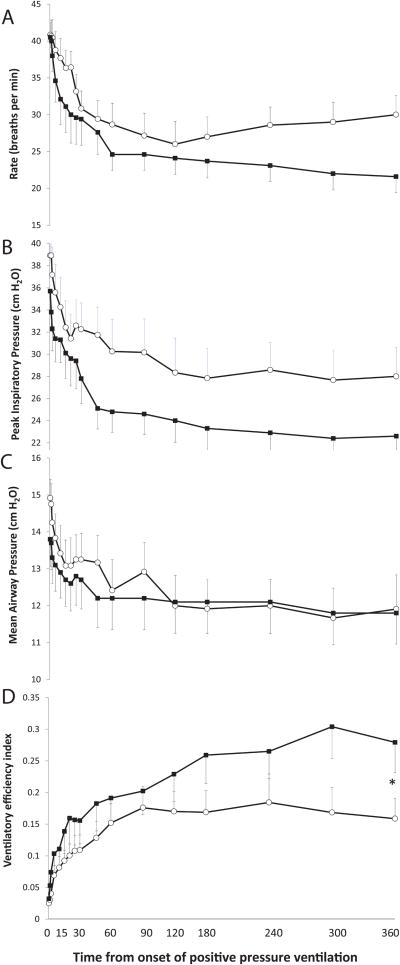

Ventilation

Baseline PaCO2 was similar in both groups of lambs (53.6 ± 3.5 vs. 54.3 ± 4 mmHg in no suction and suction groups respectively). Cord occlusion significantly increased PaCO2 (figure 3B). Following resuscitation, PaCO2 decreased in both groups. There was no significant difference in peak inspiratory pressure (PIP) or ventilator rate between the two groups (figure 4). Ventilator efficiency index (VEI) was calculated as 3800 ÷ [(PIP-PEEP)*rate*PaCO2](13). VEI was significantly higher in the suction group by 6 hours of age (figure 4D).

Figure 4.

Ventilator settings (panel A. intermittent mandatory ventilator rate, B. peak inspiratory pressure – PIP, C. mean airway pressure – MAP) and ventilator efficiency index (VEI). Mean ± SEM from asphyxiated lambs with meconium aspiration with tracheal suction at birth (n=12, shown in black squares) and no-suction (n=12, open circles) are shown. (* p < 0.05 compared to no-suction by ANOVA for the 360 min time point).

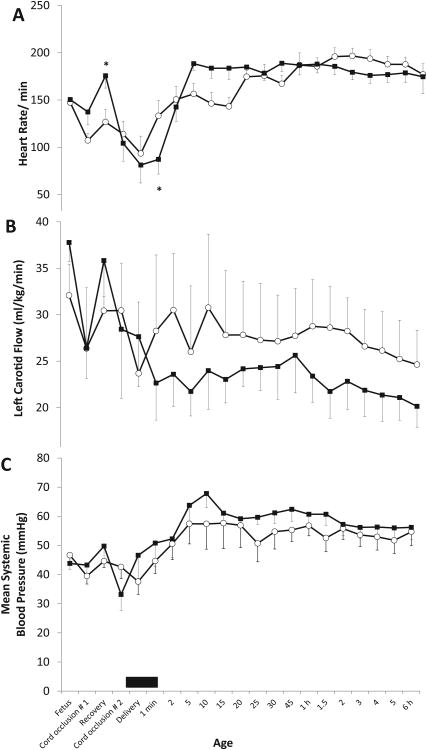

Systemic hemodynamics

Umbilical cord occlusion caused bradycardia in both groups. The heart rate was significantly higher in the suction group during the period of release of cord occlusion (figure 5A). During the period of suctioning, heart rate was significantly lower in the suction group. Positive pressure ventilation significantly improved heart rate in both groups. There was no difference in the left carotid blood flow between the two groups (figure 5B). Systemic blood pressure was similar between the two groups (figure 5C).

Figure 5.

Systemic hemodynamic changes: heart rate (panel A), left carotid blood flow (B) and mean systemic blood pressure (C). Mean ± SEM from asphyxiated lambs with meconium aspiration with tracheal suction at birth (n=12, shown in black squares) and no-suction (n=12, open circles) are shown. The black bar near the X-axis depicts the period of tracheal suctioning. (* p < 0.05 by ANOVA compared to no-suction for that specific time point).

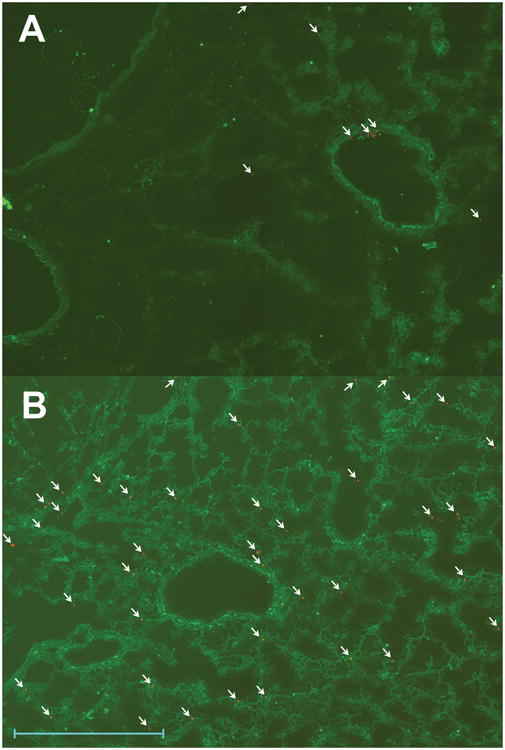

Pulmonary hemodynamics

Pulmonary arterial pressure and pulmonary blood flow decreased with cord occlusion (figure 6A). Resuscitation with PPV increased pulmonary arterial pressure accompanied by a marked increase in pulmonary blood flow. There was a trend towards elevated pulmonary arterial pressure in the suction groups over 6 hours of ventilation but this difference did not reach statistical significance (p=0.13 by ANOVA repeated measures). Left atrial pressure significantly increased following tracheal suctioning and remained elevated throughout the 6 hour period compared to no-suction group (figure 7A). Pulmonary blood flow increased significantly following resuscitation associated with a fall in PVR (figures 6B and C) in both groups.

Figure 6.

Pulmonary hemodynamic changes: mean pulmonary arterial (PA) and left atrial (LA) pressures (panel A) and left pulmonary blood flow (panel B) and pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR, panel C). Mean ± SEM from asphyxiated lambs with meconium aspiration and tracheal suction at birth (n=12, shown in black squares) and no-suction (n=12, open circles) are shown. The black bar near the X-axis depicts the period of tracheal suctioning. (* p < 0.05 compared to no suction by ANOVA repeated measures for the postnatal period compared to no suction group).

Figure 7.

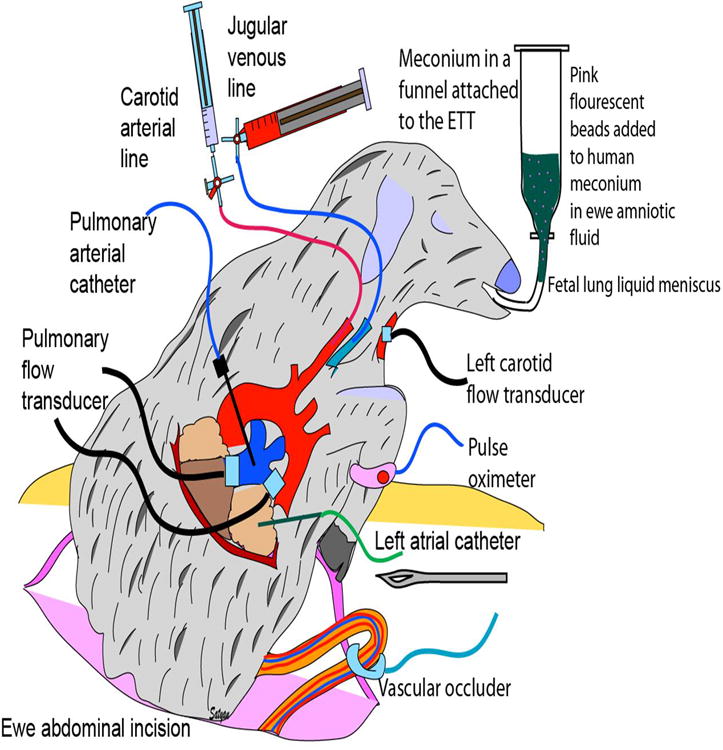

Instrumentation of a near-term fetal lamb for asphyxia and meconium aspiration studies. Catheters were placed in the right carotid artery, jugular vein, main pulmonary artery and left atrium. Flow transducers were placed around the left pulmonary artery and left carotid artery. Meconium (in 20% amniotic fluid) was placed in a funnel attached to the endotracheal tube and maintained at a height such that hydrostatic pressure did not force meconium into the lungs. Meconium solution layered over the fetal lung liquid meniscus in the endotracheal tube. The umbilical cord was occluded with a inflatable vascular occlude for 5 minutes and released for 5 minutes and occluded again for 5 minutes prior to delivery. Preductal pulse oximeter readings were obtained from the right forelimb.

Nitrotyrosine and superoxide assay

Lung 3-nitrotyrosine levels were significantly higher in the suction group (0.65 ± 0.03 ng/μg protein) compared to the no-suction group (0.47 ± 0.06 ng/μg, p < 0.05 by unpaired t-test). The protein concentration in the lungs was similar in both groups (2.6 ± 0.3 in suction vs. 2.1 ± 0.2 μg/μl in no-suction). Nitrotyrosine was uniformly detected in the airways, vasculature and alveoli by immunofluorescence (figure 1 – lower panels). The immunofluorescence was 1.8 ± 0.2 vs. 1.7 ± 0.3 × 109 arbitrary units in no-suction and suction groups respectively. There was no difference in superoxide induced chemiluminescence between suction and no-suction groups (3878 ± 597 vs. 6497 ± 1195 relative light units – RLU/mg protein, p – 0.16).

Discussion

Meconium aspiration syndrome associated with asphyxia and depression at birth continues to be a major cause of mortality and morbidity especially in settings with limited resources(14). Infants born through MSAF who require intubation for continued ventilation have a high incidence of MAS (46% vs. 0.26% in vigorous, non-intubated infants)(11). This is the first study to evaluate the effect of tracheal suctioning on hemodynamics and gas exchange in an in utero model of MAS with respiratory depression induced by asphyxia.

The majority of animal studies for meconium aspiration are conducted in postnatal (1-3 d old) piglets using human meconium instilled by positive pressure into an air-filled lung(15). In the current model, meconium is aspirated by negative pressure before birth into a fluid-filled lung, similar to the human condition and is associated with HRF with an oxygenation index of 21.6 ± 4.7 in the no-suction group and 16.4 ± 3.7 in the suction group at 6 hours of age, similar to other lamb models of MAS(16). A prior attempt to induce PPHN and HRF using a combination of asphyxia and meconium aspiration in preterm 160d gestation baboons (term ∼ 180d) was unsuccessful(17) with concomitant asphyxia reducing the severity of MAS and PPHN. In contrast, epidemiologic data suggest that asphyxia is a risk factor for developing MAS in infants born through MSAF(18).

Tracheal suctioning and removal of meconium at birth in theory should reduce airway obstruction, improve ventilation and oxygenation and prevent PPHN in MAS. Some practitioners are concerned about possible harmful effects of tracheal suctioning(19) such as vagal stimulation resulting in bradycardia, apnea, tissue trauma and risk of transmitting infection from the mother's secretions from the birth canal(20). A recent study reported increased cerebral and pulmonary blood flow following open endotracheal tube suctioning in preterm lambs(21). Three out of 15 asphyxiated lambs (20%) had cardiac arrest requiring chest compressions with suctioning in the current study (compared to no lambs with cardiac arrest in the no-suction group, p-not significant). In addition, tracheal suctioning delayed the onset of resuscitation (PPV) by approximately 100 seconds and may have prolonged hypoxic damage to various tissues. The only evidence that direct tracheal suctioning of meconium may be of value was based on comparison of suctioned babies with historic controls(22-24). The consensus statement for cardiopulmonary resuscitation states that available evidence does not support or refute the routine endotracheal suctioning of depressed infants born through MSAF(12). Because of insufficient evidence to recommend a change in practice, endotracheal suctioning in non-vigorous babies with MSAF is recommended by NRP. However, if attempted intubation is prolonged and unsuccessful, PPV should be considered, particularly if there is persistent bradycardia(25).

In the current study, tracheal suctioning resulted in recovery of approximately 60% of instilled meconium. Using an in vitro model of piglet respiratory system, Bent et al recovered 85-89% of meconium with 80-150 mmHg suction(26). In adult rabbits with meconium aspiration, suctioning with a meconium aspirator after 10 min of ventilation recovered 14.8 ± 5.5% of meconium; suction with a 8-F catheter recovered 19.5 ± 5% of instilled meconium(27). In this study, 3.5ml/kg of 20% meconium was instilled into an air-filled, healthy adult lung on PPV just before suctioning through a tracheotomy in paralyzed rabbits. In the current study, meconium was quantified by determination of fluorescence to account for dilution by lung liquid. We speculate that these differences account for higher recovery of meconium with tracheal suctioning in the current lamb model consistent with in vitro measurements(26).

To our knowledge, this is the first large animal study conducted in a model of perinatal asphyxia with lung disease where resuscitation was initiated with 21% oxygen, and then further adjusted with strict adherence to preductal pulse oximeter guidelines proposed by NRP(12,25). Maintaining preductal SpO2 in the range recommended by NRP during resuscitation and post-resuscitation phase effectively increased pulmonary blood flow (figure 6B) and decreased PVR (figure 6C). These findings validate NRP guidelines for inspired oxygen(12,25) in a model of asphyxia and lung disease.

Tracheal suctioning at birth improved oxygenation and ventilation in lambs with acute meconium aspiration. This could be a direct effect of removal of approximately 60% of meconium during suctioning and reducing large airway obstruction. However, contrary to our hypothesis, there was no improvement in pulmonary hemodynamics. The calculated PVR was similar between the two groups (figure 6C). We speculate that PVR was not significantly different as PaCO2 and PaO2 were maintained in normal physiological limits with continuous end tidal CO2 and preductal SpO2 monitoring. It is also possible that elevated PVR is secondary to chronic vascular remodeling due to in utero passage of meconium and chronic hypoxic stress. In the current model of acute MSAF without pulmonary vascular remodeling, the pulmonary hemodynamics were comparable between the suction and no suction groups. It is also possible that we did not observe changes in PVR secondary to short duration of exposure to meconium prior to resuscitation.

The left atrial pressure was higher in the suction group compared to the no-suction group (figure 6A). Elevation of left atrial pressure could be secondary to increased pulmonary venous return or left ventricular dysfunction. However, we did not observe a significant increase in pulmonary blood flow in the suction group. It is possible that there was an element of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction with elevated left atrial pressure and pulmonary venous hypertension following tracheal suction. A trend towards increased pulmonary arterial pressure (figure 6A) and lower carotid blood flow (figure 5B) in the suction group may also be suggestive of left ventricular dysfunction probably due to prolongation of hypoxic-ischemic cardiac injury.

Reactive oxygen species play an important role in the pathogenesis of neonatal pulmonary vascular disease(28). Reaction of NO with superoxide anions produces peroxynitrite, which is a highly oxidative species capable of nitrating tyrosine residues of numerous proteins leading to nitrotyrosine formation. In rat models, meconium aspiration is associated with increased nitrotyrosine(29). In spite of exposure to high inspired oxygen levels, lung 3-nitrotyrosine is significantly lower in the no-suction compared to the suction group. We could not replicate these findings by immunohistochemistry probably due to poor quantitative assessment by this technique. The mechanism of increased nitrotyrosine in the suction group is not clear as we found no difference in superoxide formation between the two groups. There are several limitations to this study. The current model represents acute perinatal aspiration and not chronic in utero aspiration of meconium associated with vascular remodeling seen in some infants with MAS. Suctioning was performed in a controlled, planned setting within 15-20 min of aspiration of meconium and may have contributed to better outcomes. The distribution of meconium was assumed to be similar to the distribution of fluorescent microspheres. The evaluation of distribution of fluorescent microspheres was limited to the right middle lobe. We did not examine lung sections from other regions of the lung as these lobes were lavaged for residual meconium. Many neonatal units administer surfactant as it is associated with reduced need for ECMO in infants with MAS and PPHN(30) although no improvement in mortality(31) or air-leaks has been observed(32). This therapy was not provided to lambs in this study to simulate resource-limited settings without access to surfactant. The sample size was based on PaO2/FiO2 ratio and may not have been adequate to assess other parameters such as hemodynamics and oxidative stress. We only studied these lambs for a 6 hour period. More prolonged observation may have yielded different results as meconium aspiration induced inflammation in the lungs may not manifest within 6 hours. However, we did not observe any significant hemodynamic or ventilator changes in the last 2 hours of study. Fresh meconium from the hospital nursery was transferred in clean specimen bags to the laboratory on the day of the study. The possibility of contaminating the meconium during transfer and introducing an infection cannot be ruled out. We only measured left carotid arterial blood flow as a surrogate of cerebral blood flow. Regional differences in cerebral blood flow were not measured by this technique. Finally, randomization was performed prior to surgery and not at the time of resuscitation.

We conclude that tracheal suctioning removed substantial amount of meconium in acute MAS and improved gas exchange. In spite of removal of approximately 60% of meconium in an acute aspiration model, suctioning did not significantly improve pulmonary hemodynamics. Suctioning was associated with adverse events such as bradycardia (including cardiac arrest), desaturation, delayed onset of PPV leading to possible left ventricular dysfunction. These findings provide evidence of benefits and risks to tracheal suctioning in a depressed large mammalian model of MSAF and may provide the basis for a randomized clinical trial in infants.

Methods

This study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at State University of New York at Buffalo. Approximately 1 g/kg of human meconium was added to warm amniotic fluid from the ewe's uterus (4 ml/kg lamb weight) to a total volume of 5 ml/kg estimated weight and homogenized to form a viscous “thick” meconium solution. Red polystyrene fluorescent beads (1 μM diameter, 1010 beads/ml, 50μL/kg, FluoSpheres 580/605; Molecular Probes, Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) were added to this solution.

Surgical protocol

The lambs were randomized to “suction” and “no-suction” groups using sealed envelopes prior to induction of maternal anesthesia with 2-3% isoflurane. Near-term gestation fetal lambs (gestational age: 137 to 142 days, term: ∼ 145 days) from time-dated pregnant ewes (Newlife Pastures, Attica NY) were exteriorized, intubated and catheters placed in the jugular vein, right carotid artery, pulmonary artery and left atrium for pressure measurements. Flow probes were placed around the left pulmonary and left carotid artery. Pulmonary vascular resistance was calculated by the following formula: PVR = (mean pulmonary arterial pressure – mean left atrial pressure) ÷ left pulmonary blood flow corrected for body weight. After endotracheal intubation, the lamb's head was tilted to the side and lung liquid was drained passively into a measuring container. After draining lung liquid, the meniscus of the fetal lung liquid was observed in the endotracheal tube 2-3 cm from the adapter. A funnel with meconium in amniotic fluid (5 ml/kg) mixed with fluorescent microspheres was connected to the endotracheal tube (figure 7). The meconium solution layered over the fetal lung liquid in the endotracheal tube and maintained at a height that hydrostatic pressure did not force meconium into the lungs. The umbilical cord was occluded for 5 min using an inflatable vascular occluding device resulting in approximately 10-15 gasps. Umbilical cord occlusion was released for 5 min to allow the lamb to recover and then occlusion was repeated for 5 more minutes. Deep, gasping respirations aspirated meconium into the lung. At the end of this period, the endotracheal tube that was used to deliver meconium was removed. The umbilical cord was cut (delivery time or time ‘0’) and lamb was placed under a radiant warmer.

Initial resuscitation was carried out as per NRP guidelines. Positive pressure ventilation was initiated with 21% oxygen. If heart rate was < 60/min after 30 seconds of effective positive pressure ventilation, chest compressions were provided (3:1 compression to ventilation ratio) and inspired oxygen was increased to 100%. If heart rate remained < 60/min after one minute of effective ventilation with 100% oxygen and chest compressions, intravenous epinephrine at 0.01mg/kg was administered and repeated every 3 minutes until heart rate improved.

Protocol in “no tracheal suction” group

Lambs that were randomized to the “no-suction” arm were reintubated with a new 4.5 cuffed endotracheal tube and ventilated using a Servo ventilator with initial pressures of 35/5 cm H2O, rate 40/min and 21% oxygen. Oxygen saturations were monitored in the right foreleg using Masimo pulse oximeter (Rad 7, Masimo Corporation, Irvine, CA). These initial settings are similar to other studies in lambs with MAS (16). High PIP was required for the first few minutes to achieve adequate tidal volume (8-10ml/kg) and gradually correct PaCO2 levels in asphyxiated lambs. Inspired oxygen concentration was titrated to maintain preductal saturations recommended by NRP (60 to 65% in the 1st min and gradually increasing to 80-85% at 5 min)(25). Frequent blood gases (fetal baseline, with each episode of cord occlusion and at 1 min, 2 min, and every 5 min for 30 min after onset of PPV and subsequently every 15 min for 6h) were evaluated. Ventilator settings were adjusted to target PaCO2 of 40-45 mmHg (end tidal CO2 of 35 to 40 mmHg), target pH of 7.30 to 7.40 and preductal pulse oximetry at 90 to 95%. The time from cutting the cord (“birth”) to initiation of ventilation was recorded.

Protocol – “tracheal suction” group

The mouth and posterior pharynx were suctioned and a new 4.5 endotracheal tube was inserted through the glottis. Using a disposable meconium aspirator (Neotech products, Valencia, CA), direct wall suction (80-100mmHg) was applied to the endotracheal tube and the tube was slowly withdrawn over 3-5 seconds. The aspirated meconium was collected from the meconium aspiratorfor calculating fluorescence. The meconium adhering to the endotracheal tube that was withdrawn during suctioning was washed with approximately 15 ml of saline solution and these washings were preserved. The total amount of fluorescence in the aspirated meconium and the washings from the endotracheal tube was used to quantitate the percent of meconium removed by suctioning. The lamb was reintubated with a fresh endotracheal tube and resuscitation with positive pressure ventilation was initiated. Ventilation protocol was similar to that described in the previous paragraph. Suctioning was not repeated for more meconium because of severe bradycardia.

Ventilation and monitoring for 6 hours

Blood gases, PVR, left carotid blood flow and systemic blood pressure were monitored for 6 hours during mechanical ventilation. Ventilator settings and inspired oxygen concentration were continuously adjusted by a neonatologist based on chest excursion, tidal volume, end tidal CO2 and preductal SpO2. If PaO2 could not be maintained > 40 mmHg in spite of ventilation with 100% oxygen and mean airway pressure of 13 cm H2O (oxygenation index of >30, OI = mean airway pressure × FiO2 × 100 ÷ PaO2), inhaled NO was administered at 20 ppm (required in two lambs in “no-suction” group and data from these animals were excluded from gas exchange, hemodynamics and 3-nitrotyrosine analysis). Lambs were infused with a balanced salt solution (Dextrose 10% with 70 mEq/L of sodium, 70 mEq/L of chloride, 40 mEq/L of potassium and 40 mEq/L of bicarbonate) at 100 ml/kg/day. Preliminary experiments demonstrated that this fluid therapy resulted in maintenance of normal electrolyte values and slow resolution of metabolic acidosis in asphyxiated lambs. Fluid composition and rate were adjusted based on serum electrolyte values. Sedation was maintained with ketamine infusion (5-7 mg/kg/h and titrated based on heart rate, blood pressure and response to toe pinch) and boluses of diazepam (0.5 mg/kg/dose).

Meconium quantification in the lungs

After 6 hours of ventilation, lambs were euthanized with an overdose of pentobarbital (Fatalplus Vortech Pharmaceuticals, Dearborn, MI) and lungs were removed. The right middle lobe was tied off at the bronchus and removed for fluorescent microscopic examination. The fluorescence in the lavage from the remaining lung was measured to estimate meconium in the airway and expressed as a percentage of instilled meconium. Peripheral lung sections from the right middle lobe were examined under the microscope to evaluate quantity and distribution of fluorescence (estimated as fluorescent particles per unit area of the lung).

Nitrotyrosine in lung tissue

Lung tissue protein concentration was determined using DC protein assay (BioRad, Hercules, CA). A competitive ELISA assay (Cell Biolabs, San Diego, CA) was performed following the manufacturer's instructions and using a Spectramax 190 plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Nitrotyrosine content was expressed as ng/μg of lung protein.

Nitrotyrosine and microsphere fluorescence

The middle lobe of the right lung was inflation fixed with O.C.T (Optimum Cutting Temperature compound) Tissue Tek – (Sakura Finetek USA, Torrance, CA) and was stained for 3-nitrotyrosine as previously described(33). Excitation-emission spectra settings of 495-519 nM for the green 3-nitrotyrosine, and 549 to 562 nM for red microsphere signal were used for photographs captured with Zeiss Axio Cam digital camera. Background corrected fluorescent intensity was quantified using Image J software.

Lucigenin-enhanced chemiluminescence assay

Lung sample homogenates were homogenized and spun at 800×g for 15min, the supernatant and pellet fractions were tested using the method described.(34,35) Each sample was run in triplicate. Quenching of the signal in the presence of diphenyleneiodonium (DPI, 10-6 M), blocking NADPH oxidase, and Tiron (10-5 M), a superoxide scavenger (both from Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was checked to confirm the specificity of the test o superoxide. Absolute luminescence (relative light unit, RLU/sec), analyzed on a Bio-Tec Synergy HT luminescence plate reader was evaluated in a kinetic profile read every 4 minutes for 1 hour. The samples were normalized to protein using BioRad kit.

Sample size calculation

In a previous study of asphyxiated lambs, the PaO2/FiO2 ratio within each subject group was normally distributed with a standard deviation 14 mmHg(36). If the true difference in the no-suction and suction group mean was 17mmHg, we needed to study 12 lambs in each group to be able to reject the null hypothesis that the population means of the experimental and control groups were equal with probability (power) 0.8. The Type I error probability associated with this test of this null hypothesis was 0.05(37).

Statistical analysis

Hemodynamic and ventilation parameters were continuously collected using Biopac software (Biopac Systems Inc, Goleta, CA) and compared by ANOVA repeated measures over the 6 hour period of ventilation using Statview 4.0 software (Abacus Corporation, Berkeley, CA). Differences in birth weight, aspirated meconium (fluorescent beads), 3-nitrotyrosine and ventilator settings / hemodynamic parameters at individual time points were analyzed by an unpaired ‘t’ test or ANOVA.

Acknowledgments

Statement of financial support: American Academy of Pediatrics, Neonatal Resuscitation Program (SL) and 1R01HD072929-0 (SL) and Department of Pediatrics, University at Buffalo, Buffalo NY

Footnotes

Category of study: Translational

Conflict of interest: Dr. Lakshminrusimha is a member of the speaker's bureau for Ikaria

References

- 1.Bacsik RD. Meconium aspiration syndrome. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1977;24:463–79. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(16)33457-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dillard RG. Neonatal tracheal aspiration of meconium-stained infants. The J Pediatr. 1977;90:163–4. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(77)80801-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fox WW, Gutsche BB, DeVore JS. A delivery room approach to the meconium aspiration syndrome (MAS). Immediate intubation, endotracheal suction, and oxygen administration can reduce morbidity and mortality. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1977;16:325–8. doi: 10.1177/000992287701600405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goodlin RC. Suppression of fetal breathing to prevent aspiration of meconium. Obstetrics and gynecology. 1970;36:944–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goodlin RC. The prevention of meconium aspiration in labor using amnioinfusion. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;74:430–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fraser WD, Hofmeyr J, Lede R, et al. Amnioinfusion for the prevention of the meconium aspiration syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:909–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vain NE, Szyld EG, Prudent LM, Wiswell TE, Aguilar AM, Vivas NI. Oropharyngeal and nasopharyngeal suctioning of meconium-stained neonates before delivery of their shoulders: multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:597–602. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16852-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wiswell TE, Gannon CM, Jacob J, et al. Delivery room management of the apparently vigorous meconium-stained neonate: results of the multicenter, international collaborative trial. Pediatrics. 2000;105:1–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kattwinkel J. Textbook of Neonatal Resuscitation. 6. Elk Grove Village IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aub-Shaweesh JM. Respiratory disorders in preterm and term infants. In: Martin RJ, Fanaroff AA, Walsh MC, editors. Fanaroff and Martin's Neonatal Perinatal Medicine. 9. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2010. pp. 1157–60. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al Takroni AM, Parvathi CK, Mendis KB, Hassan S, Reddy I, Kudair HA. Selective tracheal suctioning to prevent meconium aspiration syndrome. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1998;63:259–63. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(98)00172-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perlman JM, Wyllie J, Kattwinkel J, et al. Part 11: Neonatal resuscitation: 2010 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science With Treatment Recommendations. Circulation. 2010;122:S516–38. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.971127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeng MJ, Yang SS, Wolfson MR, Shaffer TH. Perfluorochemical (PFC) combinations for acute lung injury: an in vitro and in vivo study in juvenile rabbits. Pediatr Res. 2003;53:81–8. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200301000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Velaphi S, Van Kwawegen A. Meconium aspiration syndrome requiring assisted ventilation: perspective in a setting with limited resources. Journal of perinatology : official journal of the California Perinatal Association. 2008;28(Suppl 3):S36–42. doi: 10.1038/jp.2008.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wiswell TE, Peabody SS, Davis JM, Slayter MV, Bent RC, Merritt TA. Surfactant therapy and high-frequency jet ventilation in the management of a piglet model of the meconium aspiration syndrome. Pediatr Res. 1994;36:494–500. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199410000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simpson CM, Smolich JJ, Shekerdemian LS, Penny DJ. Urotensin-II contributes to pulmonary vasoconstriction in a perinatal model of persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn secondary to meconium aspiration syndrome. Pediatr Res. 2010;67:150–7. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181c345ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cornish JD, Dreyer GL, Snyder GE, et al. Failure of acute perinatal asphyxia or meconium aspiration to produce persistent pulmonary hypertension in a neonatal baboon model. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;171:43–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(94)70075-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsieh TK, Su BH, Chen AC, Lin TW, Tsai CH, Lin HC. Risk factors of meconium aspiration syndrome developing into persistent pulmonary hypertension of newborn. Acta Paediatr Taiwanica. 2004;45:203–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Velaphi S, Vidyasagar D. The pros and cons of suctioning at the perineum (intrapartum) and post-delivery with and without meconium. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2008;13:375–82. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Dyke RB, Spector SA. Transmission of herpes simplex virus type 1 to a newborn infant during endotracheal suctioning for meconium aspiration. Pediatr Infect Dis. 1984;3:153–6. doi: 10.1097/00006454-198403000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galinsky R, Moss TJ, Polglase GR, Hooper SB. Intrauterine inflammation alters cardiopulmonary but not cerebral hemodynamics during open endotracheal tube suction in preterm lambs. Pediatr Res. 2013;74:48–53. doi: 10.1038/pr.2013.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carson BS, Losey RW, Bowes WA, Jr, Simmons MA. Combined obstetric and pediatric approach to prevent meconium aspiration syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1976;126:712–5. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(76)90525-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gregory GA, Gooding CA, Phibbs RH, Tooley WH. Meconium aspiration in infants--a prospective study. J Pediatr. 1974;85:848–52. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(74)80358-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ting P, Brady JP. Tracheal suction in meconium aspiration. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1975;122:767–71. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(75)90585-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kattwinkel J, Perlman JM, Aziz K, et al. Part 15: neonatal resuscitation: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2010;122:S909–19. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.971119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bent RC, Wiswell TE, Chang A. Removing meconium from infant tracheae. What works best? Am J Dis Child. 1992;146:1085–9. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1992.02160210087028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Akazawa Y, Ishida T, Baba A, Hiroma T, Nakamura T. Intratracheal catheter suction removes the same volume of meconium with less impact on desaturation compared with meconium aspirator in meconium aspiration syndrome. Early Hum Dev. 2010;86:499–502. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wedgwood S, Steinhorn RH. Role of Reactive Oxygen Species in Neonatal Pulmonary Vascular Disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013 doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu MP, Du LZ, Chen XX, Gu WZ. Meconium aspiration increases iNOS expression and nitrotyrosine formation in the rat lung. World J Pediatr. 2006:61–6. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lotze A, Mitchell BR, Bulas DI, Zola EM, Shalwitz RA, Gunkel JH. Multicenter study of surfactant (beractant) use in the treatment of term infants with severe respiratory failure. Survanta in Term Infants Study Group. J Pediatr. 1998;132:40–7. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(98)70482-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.El Shahed AI, Dargaville P, Ohlsson A, Soll RF. Surfactant for meconium aspiration syndrome in full term/near term infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007:CD002054. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002054.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Polin RA, Carlo WA Committee On F, Newborn. Surfactant replacement therapy for preterm and term neonates with respiratory distress. Pediatrics. 2014;133:156–63. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lakshminrusimha S, Russell JA, Wedgwood S, et al. Superoxide dismutase improves oxygenation and reduces oxidation in neonatal pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:1370–7. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200605-676OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller AA, Drummond GR, Schmidt HH, Sobey CG. NADPH oxidase activity and function are profoundly greater in cerebral versus systemic arteries. Circ Res. 2005;97:1055–62. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000189301.10217.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Streeter EY, Badoer E, Woodman OL, Hart JL. Effect of type 1 diabetes on the production and vasoactivity of hydrogen sulfide in rat middle cerebral arteries. Physiol Rep. 2013;1:e00111. doi: 10.1002/phy2.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lakshminrusimha S, Steinhorn RH, Wedgwood S, et al. Pulmonary hemodynamics and vascular reactivity in asphyxiated term lambs resuscitated with 21 and 100% oxygen. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2011;111:1441–7. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00711.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dupont WD, Plummer WD., Jr Power and sample size calculations for studies involving linear regression. Control Clin Trials. 1998;19:589–601. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(98)00037-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]