Abstract

Background

Individuals entering jails have high rates of sexually transmitted infections (STI) but there are few data on STI in the post-incarceration period. This study aimed to describe rates of chlamydia, gonorrhea and syphilis infection among individuals released from Marion County (Indianapolis), Indiana jails.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of individuals incarcerated in Marion County, Indiana jails from 2003–2008 (N=118,670). We linked county jail and public health data to identify individuals with positive STI test results in the one-year following release from jail. Rates per 100,000 individuals and cox proportional hazard analyses were performed for each STI, stratified by demographic, STI and jail characteristics.

Results

We found significantly higher rates of STI in this cohort than in the general population, with rates in the one-year following release being 2 to 7 times higher for chlamydia, 5 to 24 times higher for gonorrhea, and 19 to 32 times higher for syphilis compared to rates in the general population. Characteristics most associated with increased risk of a positive STI test among this cohort were younger age for chlamydia and gonorrhea, older age for syphilis, black race for men, being jailed for prostitution for women, history of STI, and history of prior incarceration.

Conclusions

This study found high rates of STIs among a cohort of individuals recently released from jail and identified a number of risk factors. Further study is needed to improve targeted STI testing and treatment among this high-risk population.

Keywords: Sexually transmitted infections, Jail, Incarceration, Epidemiology

INTRODUCTION

City and county jails in the United States record almost 12 million admissions and releases every year, representing 9 million unique individuals.1 Several studies show that individuals entering jail have a high prevalence of sexually transmitted infections (STI)2–4; however, there are few data on STI positivity among this population following release. Given the current limitations of jail-based STI services,5 it is likely that a portion of STI positivity in the post-incarceration period reflects untreated or undiagnosed STI acquired prior to or during incarceration as well as STI acquired post-release. Furthermore, the period following release from jail is often characterized by high-risk sexual behaviors, including unprotected sex, concurrent sexual partners, sex for money, and drug and alcohol use.6,7 Environmental-level factors, like poverty, unemployment, and even physical neighborhood deterioration, may also impact STI risk following release from jail8–10 but there are few data on this population.

Understanding the burden of and risk for STI following release from jail is essential to inform public health strategies on STI testing and prevention in this vulnerable population.11–13 Untreated STI can lead to increased healthcare costs and serious health problems, particularly for women,14 and a lack of access to STI services likely contribute to furthering a cycle of poor health and disadvantage among justice-involved individuals.15 Using available population-level public health data, we investigated STI test positivity, including chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis, and factors associated with positivity among individuals in the one-year after release from jail in a large metropolitan area.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of jailed men and women in Marion County (Indianapolis), Indiana with individually linked STI positive test result data to estimate the overall prevalence of chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis infection and factors associated with STI positivity in the one-year period after a jail stay. There are two main jail facilities within Marion County and both are included in this analysis. These facilities do house juveniles who are charged with more serious offenses, though the majority of juvenile offenders are sent to the Juvenile Detention Center, which is not included in this analysis. Jail stay data were obtained in collaboration with the Marion County Sheriff’s Office, and STI positivity data were obtained in collaboration with Marion County Health Department. Data on jail stays from July 1, 2003 – April 30, 2008 and STI positivity data from July 1, 2000 – April 30, 2009 were included. STI positivity data were included for a wider date range so that we could obtain a history of STI infection during the 36 months prior to the first possible jail stay date, and infections diagnosed during at least the 12 months after the last possible jail release date. Individuals from jail stay data were linked to STI positivity records with identifiers including first and last name, gender, month, day and year of birth, and social security number, using a probabilistic matching algorithm described elsewhere.16,17 Multiple probabilistic matching algorithms were performed, with different weights given to different identifiers to reduce the likelihood of dependence on a single identifier. We reviewed pair probabilities from all sets of the matching algorithm output to identify threshold probabilities above which the pairs were considered true matches. Pairs above threshold in each algorithm output were merged to identify all likely matches between the incarceration and clinical data sources. All individuals with one or more jail stays between July 1, 2003 and April 30, 2008 were included in the study, and there were no exclusion criteria. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Indiana University School of Medicine in Indianapolis, Indiana with a waiver of informed consent and by the Marion County Sheriff’s Office.

Measures

STI Positivity Data

The primary outcome measure for this study was a positive test result for chlamydia, gonorrhea, or syphilis in the one year after release from jail. The lack of this outcome did not imply a lack of infection, as our data source did not identify those who tested negative or individuals not tested. Positivity for the vast majority of chlamydia and gonorrhea were defined by nucleic acid amplification tests on urine, cervical swab, or urethral swab specimens, though the type of test was not specified. Positivity for syphilis (primary or secondary) was defined by rapid plasma reagin test or venereal disease research laboratory test as an antibody titer >1:8, as commonly reported elsewhere,18 regardless of previous positive tests. In the case of a positive syphilis test, only 1 positive test result in the one-year after release from jail was included to avoid potential double counting of the same infection.

Jail Stay Data

Various demographic, clinical, and crime characteristics were described and analyzed, including gender, age, race, history of STI infection (prior 36 months to jail stay), history of previous jail stay, length of jail stay, and reason for jail stay (“charge”). Charge was categorized based on the Unified Crime Report classifications.19 Neighborhood characteristics were described using geocoded residential address data at time of jail stay.

Analyses

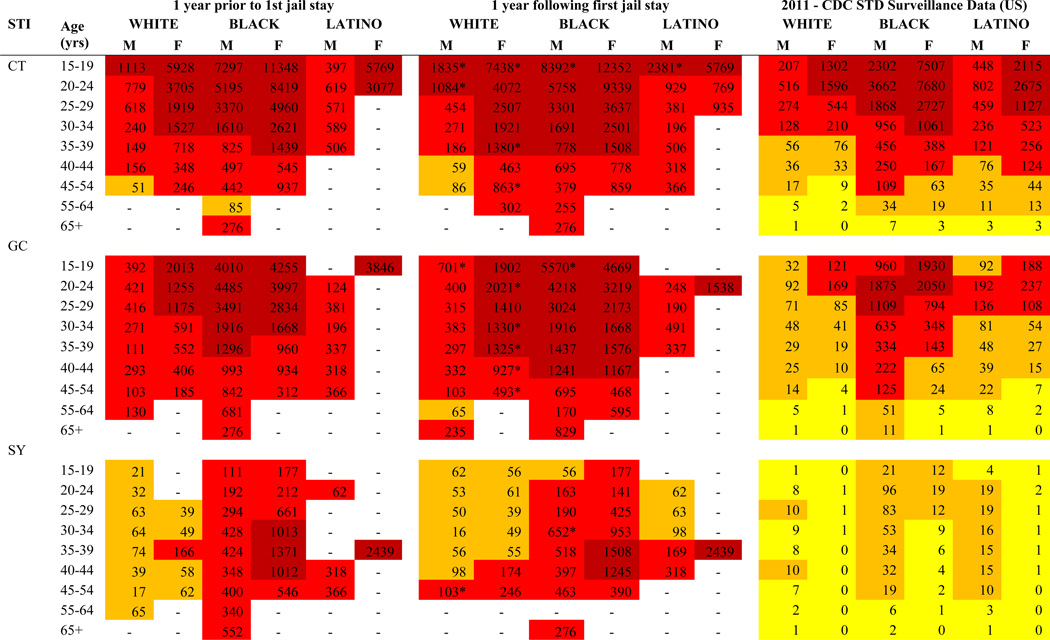

Descriptive statistics were calculated using demographic, STI, jail history, and neighborhood characteristics based on the first jail stay during the study period. Rates of chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis positivity per 100,000 people were calculated in the periods 12 months before and 12 months after the first jail stay and were stratified by gender, age, and race. Pre- and post-incarceration rates of STI positivity were compared as well as compared to rates published by the 2011 CDC STD Surveillance Report.14 The results are color-coded to assist in illustrating overall trends between the three column categories: dark red indicates rates over 1,000 per 100,000; lighter red indicates rates between 100 and 999 per 100,000, orange/yellow indicates rates between 10 and 99 per 100,000, and light yellow indicates rates less than 10 per 100,000. Cells with fewer than 10 individuals are indicated by a dash (−) and were not included. Two-tailed p-values were calculated to test for significant differences in rates between pre- to post-incarceration. Cox proportional hazard analyses were performed for each STI and stratified by gender while controlling for age, race, STI history, charge, length of stay, and jail history to investigate associations between STI positivity in the post-incarceration period and demographic, clinical, and other factors. All jail stays were used for hazard analyses, censoring time after a subsequent jail stay in the same year so that time periods to the same STI were not double counted. Neighborhood characteristics were not significantly associated with STI risk in the regression model and were omitted from Cox proportional hazard analysis. The period prevalence of each STI was calculated for the one-year period after release from first jail stay, as well as second and third jail stay among individuals with multiple incarcerations during study period, to assess how rates of STI positivity change with subsequent interactions with the justice system. For simplicity, these results are only displayed for individuals of black or white race and aged 24 years or less, as these individuals generally had the highest rates of STI. All analyses were performed using STATA/SE version 10 (College Station, TX).20

RESULTS

Demographic characteristics

A total of 118,670 individuals were incarcerated in Marion County jails in Indiana between 2003 and 2008 and were included for analysis. At first jail stay within the study period, median age was 30 years. Over three quarters of individuals jailed during this period were men, and black individuals were disproportionately represented (42%) (Table 1). Seven percent of individuals were diagnosed with an STI in the 36 months prior to their first jail stay in the study period, with chlamydia being the most common (7%). More than half of jail stays were less than 48 hours (64%), and only 9% were greater than 30 days. Intoxication-related charges were most common, and prostitution and other sex-related crimes accounted for a small percentage of overall charges. Individuals lived in Census block groups that were disproportionally poor with high unemployment rates (mean 39%), low male-to-female ratios (73% living in block groups with a male-to-female ratio less than 1), and high proportion of female-headed households (mean 39%).

Table 1.

Cohort characteristics at first jail stay

| N= | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Age (years) | ||

| <18 | 3,776 | 3.2% |

| 18–19 | 10,514 | 8.9% |

| 20–24 | 24,141 | 20.3% |

| 25–29 | 20,111 | 17.0% |

| 30–34 | 16,008 | 13.5% |

| 35–39 | 13,557 | 11.4% |

| 40–44 | 21,528 | 10.6% |

| 45–49 | 8,841 | 7.5% |

| 50+ | 9,116 | 7.7% |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | 62,055 | 52.3% |

| Black | 49,970 | 42.1% |

| Latino | 6,403 | 5.4% |

| Other/Missing | 169 | 0.1% |

| Male | 90,418 | 76.2% |

| STI history | ||

| Years since most recent STI diagnosis | ||

| Never | 110,351 | 93.0% |

| <1 year | 3,766 | 3.2% |

| 1–2 years | 2,560 | 2.2% |

| 2–3 years | 1,993 | 1.7% |

| Any history of STI diagnosis | ||

| Any STI | 11,996 | 10.1% |

| Chlamydia | 8,170 | 6.9% |

| Gonorrhea | 5,926 | 5.0% |

| Syphilis | 973 | 0.8% |

| Jail history | ||

| Length of stay (days) | ||

| 1–2 | 75,963 | 64.0% |

| 3–7 | 20,733 | 17.5% |

| 8–30 | 11,771 | 9.9% |

| >30 | 10,203 | 8.6% |

| Charge (at first jail stay)* | ||

| violent | 22,100 | 18.6% |

| property | 16,265 | 13.7% |

| drug | 16,104 | 13.6% |

| sex | 536 | 0.5% |

| prostitution | 1,176 | 1.0% |

| intoxication | 28,260 | 23.8% |

| conduct | 14,900 | 12.6% |

| status | 1,727 | 1.5% |

| other | 35,467 | 29.9% |

| Mean | SD | |

| Community characteristics (mean values based on Census block of residence) | ||

| % black | 34.3% | 33.1% |

| % Latino | 5.1% | 6.0% |

| % below 200% of Federal Poverty Line | 38.3% | 18.9% |

| % unemployed | 38.5% | 12.0% |

| % female-headed households | 39.0% | 11.0% |

| Male:Female ratio | ||

| <0.75 | 43.8% | |

| 0.75–0.90 | 9.6% | |

| 0.90–1.00 | 19.2% | |

| >1.00 | 27.4% | |

Charge was categorized using Unified Crime Report codes. For clarity, additional explanation of these classifications is included for several charge types. A violent crime charge includes four offenses: murder and non-negligent manslaughter, forcible rape, robbery, or aggravated assault. A property crime charge includes the offenses of burglary, larceny-theft, motor vehicle theft, or arson. A conduct charge corresponds to behaving in a disruptive manner (being drunk in public, for example) but presenting no serious public danger. A status charge is a violation specific to juveniles.

STI Positivity

Our cohort had significantly higher rates of STI compared to the general population; rates of chlamydia were between 2 and 7 times higher, rates of gonorrhea were between 5 and 24 times higher, and rates of syphilis were between 19 and 32 times higher compared to rates in the general population (Table 2). Chlamydia and gonorrhea infections were most common in young adults less than 30 years of age, whereas syphilis affected older adults, and all STI were diagnosed among blacks and women disproportionately. Compared to the general population, however, our cohort exhibited less divergence in STI rates between blacks and whites than individuals in the general population, meaning that rates of STI positivity were more similar among whites and blacks in our cohort. Also noteworthy was that black women in our cohort had higher rates of syphilis than men, whereas in the general population men of any race have higher syphilis rates than women. STI positivity rates were similar in the one-year prior and one-year after release from jail stay with a few exceptions. Notably, adolescent men and women and white women of any age generally had higher rates of chlamydia and gonorrhea, respectively, in the one-year after release.

Table 2.

Rates per 100,000 individuals of chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis infection

|

Abbreviations:

M = Male

F = Female

CT = Chlamydia

GC = Gonorrhea

SY = Syphilis

Adjusted Cox Proportional Hazard Ratios of STI Positivity in the 1-Year Post Release

In general, younger age (below 20 years) was associated with significantly increased likelihood of chlamydia (in men and women) and gonorrhea (in men only) test positivity in the one-year following a jail stay (Table 3). Older men and women were at greater risk for syphilis, with men 35–39 years having 6-fold greater risk and men over 50 years having a 12-fold greater risk compared to men 20–24 years of age. Compared to white men, black men were significantly more likely to have tested positivity for chlamydia (HR 3.3), gonorrhea (HR 4.0), and syphilis (HR 2.5), while black women had an increased risk only of syphilis (HR 6.0). Latino compared to white individuals was associated with a significantly decreased risk for chlamydia (in women only) and gonorrhea (in men and women), while Latino women had significantly higher risk for syphilis positivity (HR 21.3).

Table 3.

Adjusted Cox Proportional Hazard Ratios (HR) of STI Positivity in the 1-Year Post Release

| CHLAMYDIA |

GONORRHEA |

SYPHILIS |

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FEMALE | MALE | FEMALE | MALE | FEMALE | MALE | |||||||||||||

| HR | 95%CI | HR | 95%CI | HR | 95%CI | HR | 95%CI | HR | 95%CI | HR | 95%CI | |||||||

| Age (years) | ||||||||||||||||||

| <18 | 1.63 | 1.36 | 1.95 | 1.80 | 1.59 | 2.04 | 1.19 | 0.88 | 1.62 | 1.40 | 1.20 | 1.63 | 0.49 | 0.06 | 3.89 | 0.73 | 0.31 | 1.76 |

| 18–19 | 1.21 | 1.07 | 1.37 | 1.33 | 1.21 | 1.45 | 1.06 | 0.88 | 1.28 | 1.23 | 1.10 | 1.37 | 0.52 | 0.16 | 1.68 | 1.10 | 0.59 | 2.04 |

| 20–24 | 1.00 | REF | 1.00 | REF | 1.00 | REF | 1.00 | REF | 1.00 | REF | 1.00 | REF | ||||||

| 25–29 | 0.71 | 0.62 | 0.82 | 0.68 | 0.62 | 0.74 | 0.75 | 0.63 | 0.90 | 0.76 | 0.68 | 0.84 | 2.83 | 1.32 | 6.07 | 1.30 | 0.82 | 2.05 |

| 30–34 | 0.55 | 0.46 | 0.65 | 0.37 | 0.32 | 0.43 | 0.77 | 0.63 | 0.95 | 0.60 | 0.52 | 0.68 | 3.99 | 1.81 | 8.77 | 3.24 | 2.00 | 5.27 |

| 35–39 | 0.40 | 0.33 | 0.49 | 0.25 | 0.21 | 0.31 | 0.60 | 0.48 | 0.76 | 0.48 | 0.40 | 0.56 | 6.35 | 2.94 | 13.70 | 4.12 | 2.56 | 6.64 |

| 40–44 | 0.28 | 0.21 | 0.37 | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.21 | 0.37 | 0.28 | 0.49 | 0.42 | 0.33 | 0.53 | 7.90 | 3.66 | 17.05 | 4.00 | 2.37 | 6.74 |

| 45–49 | 0.25 | 0.18 | 0.35 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.15 | 0.26 | 0.17 | 0.40 | 0.33 | 0.26 | 0.42 | 7.27 | 2.92 | 18.08 | 6.13 | 3.40 | 11.06 |

| 50+ | 0.22 | 0.12 | 0.39 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.07 | 0.27 | 0.24 | 0.17 | 0.36 | 12.97 | 5.07 | 33.22 | 5.55 | 2.97 | 10.36 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||||||||||||

| white | 1.00 | REF | 1.00 | REF | 1.00 | REF | 1.00 | REF | 1.00 | REF | 1.00 | REF | ||||||

| black | 0.98 | 0.88 | 1.10 | 3.26 | 2.91 | 3.65 | 0.91 | 0.79 | 1.05 | 4.03 | 3.50 | 4.65 | 6.02 | 3.36 | 10.80 | 2.52 | 1.61 | 3.93 |

| Latino | 0.52 | 0.32 | 0.85 | 1.00 | 0.78 | 1.29 | 0.26 | 0.09 | 0.75 | 0.64 | 0.43 | 0.94 | 21.30 | 4.08 | 111.28 | 1.67 | 0.72 | 3.84 |

| other/missing | 0.42 | 0.11 | 1.60 | 0.00 | . | . | 1.92 | 0.41 | 8.96 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | . | . |

| STI history (most recent diagnosis, years) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Never | 1.00 | REF | 1.00 | REF | 1.00 | REF | 1.00 | REF | 1.00 | REF | 1.00 | REF | ||||||

| <1 year | 3.46 | 3.06 | 3.92 | 3.02 | 2.75 | 3.31 | 2.85 | 2.44 | 3.34 | 4.09 | 3.71 | 4.50 | 16.61 | 10.55 | 26.13 | 8.96 | 6.37 | 12.60 |

| 1–2 years | 2.73 | 2.37 | 3.14 | 2.41 | 2.17 | 2.66 | 2.38 | 1.99 | 2.84 | 3.10 | 2.78 | 3.45 | 14.56 | 9.56 | 22.17 | 9.62 | 6.83 | 13.55 |

| 2–3 years | 2.30 | 1.98 | 2.67 | 2.14 | 1.91 | 2.40 | 1.97 | 1.63 | 2.38 | 2.90 | 2.58 | 3.25 | 10.77 | 7.25 | 15.99 | 6.81 | 4.73 | 9.80 |

| Charge | ||||||||||||||||||

| Violent | 1.05 | 0.96 | 1.16 | 1.04 | 0.98 | 1.11 | 1.03 | 0.91 | 1.16 | 1.10 | 1.03 | 1.18 | 1.22 | 0.86 | 1.73 | 1.09 | 0.89 | 1.34 |

| Property | 1.05 | 0.96 | 1.14 | 1.07 | 1.00 | 1.14 | 1.04 | 0.93 | 1.15 | 1.03 | 0.95 | 1.11 | 1.11 | 0.80 | 1.52 | 1.69 | 1.35 | 2.11 |

| Drug | 1.27 | 1.16 | 1.39 | 1.09 | 1.03 | 1.15 | 1.12 | 0.99 | 1.26 | 1.03 | 0.97 | 1.10 | 1.27 | 0.96 | 1.66 | 0.95 | 0.74 | 1.21 |

| Prostitution | 1.96 | 1.72 | 2.23 | 0.84 | 0.48 | 1.48 | 1.59 | 1.37 | 1.86 | 1.39 | 0.88 | 2.21 | 2.21 | 1.68 | 2.91 | 5.09 | 2.39 | 10.85 |

| Intoxication | 0.82 | 0.72 | 0.92 | 0.93 | 0.85 | 1.01 | 0.79 | 0.69 | 0.92 | 0.94 | 0.84 | 1.04 | 1.09 | 0.75 | 1.60 | 1.13 | 0.87 | 1.48 |

| Conduct | 0.99 | 0.90 | 1.10 | 1.10 | 1.04 | 1.16 | 1.01 | 0.88 | 1.15 | 1.06 | 1.00 | 1.13 | 0.98 | 0.71 | 1.37 | 0.93 | 0.75 | 1.17 |

| Length of stay (days) | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1–2 | 1.00 | REF | 1.00 | REF | 1.00 | REF | 1.00 | REF | 1.00 | REF | 1.00 | REF | ||||||

| 3–7 | 0.83 | 0.77 | 0.89 | 0.94 | 0.89 | 0.99 | 0.94 | 0.86 | 1.03 | 0.94 | 0.89 | 0.99 | 0.77 | 0.61 | 0.97 | 0.87 | 0.72 | 1.06 |

| 8–30 | 0.87 | 0.80 | 0.95 | 0.88 | 0.83 | 0.94 | 1.00 | 0.90 | 1.10 | 0.90 | 0.85 | 0.96 | 0.99 | 0.78 | 1.26 | 1.08 | 0.88 | 1.33 |

| >30 | 0.88 | 0.81 | 0.97 | 0.83 | 0.78 | 0.88 | 0.87 | 0.78 | 0.98 | 0.84 | 0.79 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.72 | 1.14 | 0.99 | 0.80 | 1.22 |

| Jail history (most recent jail stay, days) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Never | 1.00 | REF | 1.00 | REF | 1.00 | REF | 1.00 | REF | 1.00 | REF | 1.00 | REF | ||||||

| <30 | 2.52 | 2.27 | 2.78 | 1.47 | 1.35 | 1.59 | 2.44 | 2.14 | 2.77 | 1.41 | 1.27 | 1.56 | 1.62 | 1.20 | 2.18 | 1.17 | 0.86 | 1.60 |

| 30–365 | 1.83 | 1.71 | 1.96 | 1.35 | 1.29 | 1.42 | 1.92 | 1.76 | 2.10 | 1.28 | 1.21 | 1.34 | 1.30 | 1.06 | 1.60 | 0.97 | 0.82 | 1.15 |

| >365 | 1.27 | 1.17 | 1.38 | 1.08 | 1.02 | 1.15 | 1.34 | 1.21 | 1.49 | 0.95 | 0.89 | 1.01 | 0.86 | 0.66 | 1.14 | 1.05 | 0.88 | 1.24 |

Previous diagnosis of STI in the 36 months prior to incarceration was the only factor that significantly increased the likelihood of all types of STI in both men and women, with more recent STI infection (less than 12 months before incarceration) associated with greater risk. Prostitution was the only charge significantly associated with all infections in women in the post-release period (chlamydia HR 2.0, gonorrhea HR 1.6, syphilis HR 2.2), while for men a prostitution charge was associated only with syphilis (HR 2.4). Drug-related charge was significantly associated with increased risk among men and women for chlamydia, but not gonorrhea or syphilis. A jail stay of longer than 2 days had a significantly decreased risk of chlamydia and gonorrhea positivity. Finally, a history of previous incarceration within the study period was significantly associated with increased risk for all STI among men and women, with the strongest increased risk associated with a more recent incarceration.

Multiple Jail Stays and STI Positivity Risk

Many individuals were incarcerated more than once over the course of the study period, with 44.7% in jail 2 or more times. Individuals with 2 or more jail stays had higher rates of STI during the 12 months before and after first jail stay, compared to the overall cohort (Table 4). For example, among all black women under 18 years of age, the period prevalence of chlamydia and gonorrhea after first jail stay was 12.2% and 4.6%, respectively. Among black women under 18 years with 2 or more jails stays, the period prevalence for chlamydia and gonorrhea after first jail stay was 29.6% and 11.1%, respectively.

Table 4.

Rate of STIs 1-year prior and 1-year post jail stay

| 1st jail stay among all individuals |

1st jail stay among those with 2+ jail stays |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 year PRIOR | 1 year POST | 1 year PRIOR | 1 year POST | |||||||||||

| demographic category | N | CT | GC | SY | CT | GC | SY | N | CT | GC | SY | CT | GC | SY |

| black female <18yo | 304 | 11.2% | 3.9% | 0.0% | 12.2% | 4.6% | 0.0% | 54 | 35.2% | 9.3% | 0.0% | 29.6% | 11.1% | 0.0% |

| white female <18yo | 423 | 8.3% | 2.8% | 0.0% | 9.7% | 2.1% | 0.0% | 69 | 18.8% | 7.2% | 0.0% | 15.9% | 8.7% | 0.0% |

| black female 18–19yo | 1,388 | 11.4% | 4.3% | 0.2% | 12.4% | 4.7% | 0.2% | 542 | 20.7% | 7.6% | 0.4% | 24.0% | 10.1% | 0.6% |

| white female 18–19yo | 1,365 | 5.2% | 1.8% | 0.0% | 6.7% | 1.8% | 0.1% | 436 | 13.1% | 4.8% | 0.0% | 17.0% | 4.8% | 0.2% |

| black female 20–24yo | 2,827 | 8.4% | 4.0% | 0.2% | 9.3% | 3.2% | 0.1% | 1,164 | 15.4% | 6.8% | 0.5% | 17.0% | 6.4% | 0.3% |

| white female 20–24yo | 3,266 | 3.7% | 1.3% | 0.0% | 4.1% | 2.0% | 0.1% | 1,106 | 9.0% | 2.9% | 0.0% | 10.5% | 4.6% | 0.2% |

| black male <18yo | 1,723 | 8.1% | 3.6% | 0.1% | 9.5% | 5.7% | 0.1% | 675 | 11.9% | 5.8% | 0.1% | 13.2% | 9.2% | 0.1% |

| white male <18yo | 1,181 | 2.1% | 0.5% | 0.1% | 2.6% | 1.0% | 0.1% | 304 | 2.6% | 0.7% | 0.0% | 3.9% | 1.6% | 0.0% |

| black male 18–19yo | 3,663 | 6.9% | 4.2% | 0.1% | 7.9% | 5.5% | 0.1% | 2,365 | 9.0% | 5.2% | 0.2% | 10.2% | 7.3% | 0.1% |

| white male 18–19yo | 3,670 | 0.8% | 0.4% | 0.0% | 1.6% | 0.6% | 0.1% | 1,577 | 1.5% | 0.4% | 0.0% | 3.2% | 1.0% | 0.1% |

| black male 20–24yo | 6,756 | 5.2% | 4.5% | 0.2% | 5.8% | 4.2% | 0.2% | 4,377 | 6.9% | 6.0% | 0.3% | 7.5% | 5.9% | 0.2% |

| white male 20–24yo | 9,504 | 0.8% | 0.4% | 0.0% | 1.1% | 0.4% | 0.1% | 3,731 | 1.4% | 0.8% | 0.1% | 2.1% | 0.8% | 0.1% |

| others | 82600 | 0.9% | 0.9% | 0.2% | 1.0% | 0.9% | 0.3% | 36697 | 1.7% | 1.6% | 0.5% | 1.8% | 1.8% | 0.5% |

|

2nd jail stay |

3rd jail stay |

|||||||||||||

| 1 year PRIOR | 1 year POST | 1 year PRIOR | 1 year POST | |||||||||||

| demographic category | N | CT | GC | SY | CT | GC | SY | N | CT | GC | SY | CT | GC | SY |

| black female <18yo | 26 | 50.0% | 19.2% | 0.0% | 34.6% | 19.2% | 0.0% | - | ||||||

| white female <18yo | 30 | 20.0% | 10.0% | 0.0% | 26.7% | 13.3% | 0.0% | - | ||||||

| black female 18–19yo | 319 | 25.1% | 11.6% | 0.3% | 22.9% | 11.3% | 0.0% | 107 | 37.4% | 14.0% | 0.0% | 18.7% | 10.3% | 0.0% |

| white female 18–19yo | 305 | 15.7% | 6.2% | 0.3% | 17.4% | 5.2% | 0.3% | 132 | 20.5% | 7.6% | 0.0% | 25.0% | 7.6% | 0.8% |

| black female 20–24yo | 1,223 | 14.4% | 8.2% | 0.2% | 17.3% | 6.5% | 0.3% | 622 | 17.7% | 10.5% | 0.3% | 15.4% | 7.9% | 0.5% |

| white female 20–24yo | 1,106 | 10.6% | 3.8% | 0.0% | 9.5% | 4.8% | 0.2% | 595 | 10.9% | 5.4% | 0.0% | 14.6% | 7.7% | 0.3% |

| black male <18yo | 330 | 18.5% | 7.0% | 0.6% | 16.4% | 10.3% | 0.0% | 104 | 24.0% | 9.6% | 1.9% | 24.0% | 12.5% | 0.0% |

| white male <18yo | 111 | 0.9% | 2.7% | 0.0% | 5.4% | 3.6% | 0.0% | 24 | 0.0% | 4.2% | 0.0% | 12.5% | 4.2% | 0.0% |

| black male 18–19yo | 1,988 | 10.6% | 6.5% | 0.2% | 11.8% | 8.4% | 0.1% | 1,223 | 11.3% | 9.9% | 0.2% | 12.7% | 10.3% | 0.3% |

| white male 18–19yo | 1,228 | 3.1% | 0.8% | 0.0% | 3.2% | 0.9% | 0.0% | 619 | 4.2% | 1.3% | 0.0% | 4.4% | 0.6% | 0.0% |

| black male 20–24yo | 4,373 | 7.9% | 6.4% | 0.2% | 7.5% | 6.0% | 0.2% | 3,174 | 8.9% | 7.6% | 0.2% | 8.3% | 7.0% | 0.2% |

| white male 20–24yo | 3,592 | 2.1% | 0.8% | 0.1% | 2.2% | 0.7% | 0.1% | 2,061 | 2.7% | 1.2% | 0.0% | 3.1% | 1.2% | 0.1% |

| others | 38466 | 1.7% | 1.8% | 0.4% | 1.9% | 1.8% | 0.4% | 24315 | 2.1% | 2.4% | 0.5% | 2.5% | 2.2% | 0.5% |

Abbreviations:

CT = Chlamydia

GC = Gonorrhea

SY = Syphilis

DISCUSSION

Individuals with a history of a jail stay in our cohort had significantly higher rates of chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis positivity both before and following jail stays compared to the general population. As expected, younger age was consistently associated with an increased risk of chlamydia and gonorrhea while older age was associated with an increased risk of syphilis. Previous STI diagnosis, recent jail stay, and criminal charges like prostitution and drug-related offenses were factors associated with increased STI positivity.

Several findings related to race and STI positivity were inconsistent with trends in the general population. For example, for women in this cohort, black race was not a significant risk factor for chlamydia or gonorrhea. In 2011, the CDC estimated black women had rates of chlamydia 6 times the rate of white women and gonorrhea 15 times that of white women,14 but a differential risk of STI after release from jail was not evident in this study. This finding may reflect the risk profile of incarcerated women who may be more likely to have common risk behaviors, leading to less significant differences in positivity between races. Furthermore, in 2010 black women were incarcerated (including jail and prison) at a rate 3 times that of white women.21 As white women were disproportionately underrepresented by race, white women who were jailed may have had a higher risk of infection. Interestingly, black women had considerably higher rates of syphilis than black men in this cohort, perhaps reflecting increased exposure among women engaged in commercial sex.

Few studies have investigated STI among individuals recently released from jail. In a study of 178 young men released from prison, Sosman et al. reported that at 6 months post-release, 26% tested positive during a screening program for at least one STI.22 In another study, Stein et al. found that among a group of 190 women enrolled in an alcohol intervention study, 10% tested positive for STI at 6-months post-release from a correctional facility.23 These studies had small sample sizes and inclusion based on consent for STI testing post-release.22,23 We did not find STI rates that reached these levels in this cohort, but we relied on public health data sources that did not include negative test results so we could not assess overall prevalence.

We did not assess risk behaviors so it is unclear whether individuals in this cohort had more, less, or similar risk behaviors prior to versus after incarceration. Studies have shown that men and women released from correctional settings often engage in high-risk sexual behaviors like unprotected sex, multiple sexual partners, concurrent sexual relationships, and drug and alcohol use in the period immediately following release, but few have pre-incarceration data.24–26 Our finding that certain charges like prostitution and drug offenses were generally associated with increased risk of STI positivity may serve as proxy risk behaviors, and could be used as indicators to prompt more intensive jail-based STI testing post-release.

Spending time in jail may lead to offenders being cut-off from social and sexual networks maintained prior to incarceration, and to entering new, higher risk sexual networks or adopting higher risk behaviors.27,28 It is unclear how the length of stay in jail affects these networks, given that the time spent in jail is typically only a few days, and we found that a longer jail stay (>2 days) was generally associated with a decreased risk of STI positivity after release. It is possible that individuals jailed longer than a few days were more likely to access opt-in STI testing offered through jails in Marion County, receive the necessary treatment, and thus not test positive in the one-year after release (assuming effective treatment and no reinfection). The low number of positive tests reported from jails, however, suggests that this was a small number of individuals (per 100,000 individuals, positivity rates during jail stays in the study period were 239 for chlamydia, 162 for gonorrhea, and 21 for syphilis). Repeated incarceration was associated with significantly greater risk for STI positivity. While prospectively one does not know who will be jailed more than once, repeated incarceration could serve as an indicator for targeted STI screening at subsequent jail encounters.

Upon release and reentry into society, offenders often face difficulties finding employment and housing, suffer from higher rates of morbidities and substance abuse, and have difficulties accessing healthcare.12,13,29 Neighborhood-level factors like unemployment, poverty, and female-headed households were not significantly associated with STI positivity when individual-level characteristics were included, however, there may not have been enough variability within this cohort to detect significant differences. Several studies among the general population have found neighborhood characteristics are associated with STI and other health outcomes, particularly among adolescents.30,31 A study by Dembo et al. found that community disadvantage, as defined by 4 indicators (income level, proportion minority, female-headed households, and unemployment), was significantly associated with STI independent of individual-level factors among a group of newly arrested juveniles.32 The association between STI and community-level factors among recent offenders should be further investigated.

There are several limitations of this study. First, since not all individuals (including those recently jailed) are screened routinely for STI, our findings are limited to those individuals who sought care within the county and received STI testing at in-county locations, and for whom positivity data were reported to the health department. Marion County has an active surveillance program in which positive STI test results are automatically reported to the health department from laboratories, limiting a reporting bias. Differential care-seeking behavior and/or screening may occur among this population, however, contributing to biased findings. Second, we did not have a number of important variables, including records of negative STI tests, data related to treatment, or individual-level socioeconomic data like health insurance status or behavioral data, although we attempted to use a number of proxy variables to investigate behavioral factors. Third, it is unknown whether all individuals in the disparate data sets were appropriately linked. Missing or incorrect data, the use of aliases by individuals, or legal name changes may affect the sensitivity and specificity of record linkages. It is also possible due to in or out migration that STI diagnoses were missed for certain individuals who were recently jailed. Finally, this analysis is restricted to a single metropolitan area and may not be generalizable to other urban communities. We had significantly smaller numbers of Latinos, especially Latino women, compared to whites and blacks. In addition, local events such as the syphilis outbreak during the study period may have influenced testing patterns, though it is unlikely to differentially affect the testing of jailed individuals as there are no standard testing procedures for this population.

This study found high rates of STIs among a cohort of individuals released from jail, but more data on factors related to STI risk, testing, and points of care among this population are needed. In the meantime, our data suggest that individuals recently released from jail will benefit from more regular STI testing and from increased collaboration and data sharing between public health and criminal justice systems.

Acknowledgments

This work would not have been possible without the collaboration of many partner agencies and individuals. We would like to acknowledge and thank the Marion County Sheriff’s Office, especially Lt. Colonel Louis Dezelan, Ron Meadows and Mark Reynolds (jail data) and Marion County Health Department, especially Dr. Janet Arno and Coya Campbell (STI data), for generously sharing their data and expertise in using these data. We would like to recognize Shawn Hoch’s expert management skills with these large and complex data sets. Data linkage would not be possible without the expert help of Dr. Shaun Grannis and James Egg.

Funding source: This research was supported in part by a grant (R21AI084060) to Dr. Sarah Wiehe from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Footnotes

Financial disclosure: The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the view of the Indiana University School of Medicine. The primary author had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Minton T. Jail Inmates at Midyear 2011-Statistical Tables. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2012. Apr, [Google Scholar]

- 2.Franklin WB, Katyal M, Mahajan R, Parvez FM. Chlamydia and gonorrhea screening using urine-based nucleic acid amplification testing among males entering New York City jails: a pilot study. Journal of correctional health care : the official journal of the National Commission on Correctional Health Care. 2012;18(2):120–130. doi: 10.1177/1078345811435767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mertz KJ, Schwebke JR, Gaydos CA, Beidinger HA, Tulloch SD, Levine WC. Screening women in jails for chlamydial and gonococcal infection using urine tests: feasibility, acceptability, prevalence, and treatment rates. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2002;29(5):271–276. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200205000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pathela P, Hennessy RR, Blank S, Parvez F, Franklin W, Schillinger JA. The contribution of a urine-based jail screening program to citywide male Chlamydia and gonorrhea case rates in New York City. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36(2 Suppl):S58–S61. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31815615bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Evaluation of Large Jail STD Screening Programs, 2008–2009. Atlanta: CDC/NCHHSTP/DSTDP/HSREB; 2011. Jan 26, [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramaswamy M, Freudenberg N. Sex partnerships, health, and social risks of young men leaving jail: analyzing data from a randomized controlled trial. BMC public health. 2010;10:689. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adams LM, Kendall S, Smith A, Quigley E, Stuewig JB, Tangney JP. HIV Risk Behaviors of Male and Female Jail Inmates Prior to Incarceration and One Year Post-Release. AIDS and behavior. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9990-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen D, Spear S, Scribner R, Kissinger P, Mason K, Wildgen J. "Broken windows" and the risk of gonorrhea. American journal of public health. 2000;90(2):230–236. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.2.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen DA, Mason K, Bedimo A, Scribner R, Basolo V, Farley TA. Neighborhood physical conditions and health. American journal of public health. 2003;93(3):467–471. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.3.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomas JC, Torrone EA, Browning CR. Neighborhood factors affecting rates of sexually transmitted diseases in Chicago. Journal of urban health : bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2010;87(1):102–112. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9410-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brinkley-Rubinstein L. Incarceration as a catalyst for worsening health. Health and Justice. 2013;1(3):1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freudenberg N, Daniels J, Crum M, Perkins T, Richie BE. Coming home from jail: the social and health consequences of community reentry for women, male adolescents, and their families and communities. American journal of public health. 2005;95(10):1725–1736. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.056325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lim S, Seligson AL, Parvez FM, et al. Risks of drug-related death, suicide, and homicide during the immediate post-release period among people released from New York City jails, 2001–2005. American journal of epidemiology. 2012;175(6):519–526. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Diseases Surveillance 2011. Atlanta: CDC, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD and TB Prevention; 2012. Dec, [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parrish DD, Kent CK. Access to care issues for African American communities: implications for STD disparities. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2008;35(12 Suppl):S19–S22. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31818f2ae1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu VJ, Overhage MJ, Egg J, Downs SM, Grannis SJ. An empiric modification to the probabilistic record linkage algorithm using frequency-based weight scaling. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association : JAMIA. 2009;16(5):738–745. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M3186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grannis SJ, Overhage JM, Hui S, McDonald CJ. Analysis of a probabilistic record linkage technique without human review. AMIA … Annual Symposium proceedings / AMIA Symposium. AMIA Symposium. 2003:259–263. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gottlieb SL, Pope V, Sternberg MR, et al. Prevalence of syphilis seroreactivity in the United States: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) 2001–2004. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2008;35(5):507–511. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181644bae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Federal Bureau of Investigation. Uniform Crime Reporting Handbook, 2004. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stata Statistical Software: Release 10 [computer program] College Station, Texas: StataCorp LP; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guerino P, Harrison PM, Sabol WJ. Prisoners in 2011. Washington, D.C.: Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sosman J, Macgowan R, Margolis A, et al. Sexually transmitted infections and hepatitis in men with a history of incarceration. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38(7):634–639. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31820bc86c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stein MD, Caviness CM, Anderson BJ. Incidence of sexually transmitted infections among hazardously drinking women after incarceration. Womens Health Issues. 2012;22(1):e1–e7. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2011.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rogers SM, Khan MR, Tan S, Turner CF, Miller WC, Erbelding E. Incarceration, high-risk sexual partnerships and sexually transmitted infections in an urban population. Sexually transmitted infections. 2012;88(1):63–68. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2011-050280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adams J, Nowels C, Corsi K, Long J, Steiner JF, Binswanger IA. HIV risk after release from prison: a qualitative study of former inmates. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes. 2011;57(5):429–434. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31821e9f41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morrow KM Project SSG. HIV, STD, and hepatitis risk behaviors of young men before and after incarceration. AIDS Care. 2009;21(2):235–243. doi: 10.1080/09540120802017586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grinstead OA, Faigeles B, Comfort M, et al. HIV, STD, and hepatitis risk to primary female partners of men being released from prison. Women Health. 2005;41(2):63–80. doi: 10.1300/J013v41n02_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seal DW, Eldrige GD, Kacanek D, Binson D, Macgowan RJ. A longitudinal, qualitative analysis of the context of substance use and sexual behavior among 18- to 29-year-old men after their release from prison. Social science & medicine. 2007;65(11):2394–2406. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khan M, Epperson M. Disconnected. Incarceration cuts you off from your social network--and HIV thrives on that. Positively aware : the monthly journal of the Test Positive Aware Network. 2012;24(3):36–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krieger N, Waterman PD, Chen JT, Soobader MJ, Subramanian SV. Monitoring socioeconomic inequalities in sexually transmitted infections, tuberculosis, and violence: geocoding and choice of area-based socioeconomic measures--the public health disparities geocoding project (US) Public health reports. 2003;118(3):240–260. doi: 10.1093/phr/118.3.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. The neighborhoods they live in: the effects of neighborhood residence on child and adolescent outcomes. Psychol Bull. 2000;126(2):309–337. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dembo R, Belenko S, Childs K, Wareham J, Schmeidler J. Individual and community risk factors and sexually transmitted diseases among arrested youths: a two level analysis. Journal of behavioral medicine. 2009;32(4):303–316. doi: 10.1007/s10865-009-9205-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]