Abstract

Insulin like growth factor-I (IGF-1) isoforms differ structurally in their E-domain regions and their temporal expression profile in response to injury. We and others have reported that Mechano-growth factor (MGF), which is equivalent to human IGF-1c and rodent IGF-1Eb isoforms, is expressed acutely following myocardial infarction (MI) in the mouse heart. To examine the function of the E-domain region, we have used a stabilized synthetic peptide analog corresponding to the unique 24 amino acid region E-domain of MGF. Here we deliver the human MGF E-domain peptide to mice during the acute phase (within 12 hours) and the chronic phase (8 weeks) post-MI. We assessed the impact of peptide delivery on cardiac function and cardiovascular hemodynamics by pressure-volume (P-V) loop analysis and gene expression by quantitative RT-PCR. A significant decline in both systolic and diastolic hemodynamics accompanied by pathologic hypertrophy occurred by 10 weeks post-MI in the untreated group. Delivery of the E-domain peptide during the acute phase post-MI ameliorated the decline in hemodynamics, delayed decompensation but did not prevent pathologic hypertrophy. Delivery during the chronic phase post-MI significantly improved systolic function, predominantly due to the effects on vascular resistance and prevented decompensation. While pathologic hypertrophy persisted there was a significant decline in atrial natriuretic factor (ANF) expression in the E-domain peptide treated hearts. Taken together our data suggest that administration of the MGF E-domain peptide derived from the propeptide form of IGF-1Ec may be used to facilitate the actions of IGF-I produced by the tissue during the progression of heart failure to improve cardiovascular function.

Keywords: IGF-1 isoforms, E-domain, Myocardial Infarction, Cardiovascular function

Introduction

A major consequence of myocardial infarction (MI), are the structural and functional alterations of the entire cardiovascular system that contribute to the progression of heart failure. Assessment of cardiovascular changes following MI have highlighted the pathophysiologically changes associated with adaptive compensatory responses such as LV hypertrophy and activation of the sympathetic nervous system to maintain cardiac output and mean arterial pressure. Eventually, these adaptive responses decompensate which is heralded by contractile dysfunction occurring with maladaptive chamber dilation, increased end diastolic pressures and increased peripheral vascular resistance. Treatment objectives for decompensated heart failure are directed at hemodynamic unloading, prevention of further myocardial damage, modulation of neurohormonal and inflammatory activation. During these events, local growth factors such as IGF-1 are produced by the myocardium and vasculature to mitigate the damage associated with ischemia, reactive oxygen species, inflammation and circulating levels of angiotensin II.

The insulin-like growth factors (IGFs) comprise a family of peptides which circulate in the blood and play major roles in mammalian development and growth [1]. In addition, both IGFs (IGF-I and IGF-II) function as paracrine and autocrine growth factors expressed in various tissues mediating regenerative and repair processes [2, 3]. The IGF-I gene yields a simple mature peptide (70 amino acids), but contains several alternatively spliced exons both at the 5′ and 3′-ends [4]. At the 3′-end, alternate splicing of exons 5 and 6 give rise to different E-domains, which form part of the propeptide. Cleavage of the propeptide by cellular proprotein convertases yields the mature IGF-1 peptide composed of the B, C, A, D domains encoded by exons 3 and 4 and the E-domain [5].

The first indication that IGF-1 E-domains may have biological properties were noted in bronchial epithelium due to the mitogenic activity of a synthetic peptide analog corresponding to the 23-amino acid E-domain sequence of the human pro-IGF-1Eb isoform expressed in the lungs [6]. Similarly, application of a 24-amino acid peptide analog corresponding to the unique E-domain region of MGF has been shown to have neuroprotective activity by preventing apoptosis in a model of global transient cerebral ischemia [7]. In a previously reported proof-of-concept experiment, systemic delivery of a stabilized MGF E-domain peptide analog administered at the time of myocardial infarction (MI), preserved cardiac function and prevented pathologic hypertrophy in mice [8]. Similar data were also obtained with intracoronary delivery of the MGF E-domain peptide, which provided a cardio protective effect and functional benefits independently and synergistically with IGF-1 in an ovine model of myocardial infarction [9]. Both these prior studies examined peptide analog delivery during MI and analyzed the beneficial effects within the first 2 weeks post-MI, during the onset of hypertrophic remodeling. In the present study, we examined the long term beneficial effects of the MGF E-domain peptide analog delivered during the acute phase post-MI and during the chronic phase post-MI. We analyzed cardiac function in mice at 10 weeks post-MI, a time point we have previously shown to correspond to the decompensation of compensatory hypertrophy in mice subjected to permanent coronary ligation [10].

Materials and Methods

The experiments were approved by the institutional Animal Care and Use Committee in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines.

Myocardial infarction

Male B6/SJL 3-month old mice were anesthetized with 3% isoflurane inhaled in a closed chamber and Etomidate (10 mg/kg, i.p.). Mice were intubated and connected to a rodent ventilator and additional anesthesia was regulated by delivery of 1.5% isoflurane through a vaporizer with 100% oxygen. The left anterior descending coronary artery was ligated with 8-0 silk suture 1–2 mm below the left atrium which consistently induces 45–50% infarcts as previously published [8,10].

E-domain peptide and treatments

A 24 amino acid peptide (YQPPSTNKNTKSQRRKGSTFEEHK), corresponding to the unique C-terminal E-domain of the human MGF isoform, was synthesized and purified to >90% via HPLC (Genescript Corp, NJ). The peptide was stabilized by amidating the C-terminus and switching the arginines at positions 14 and 15 to the D-stereoisomer. Micro-osmotic pumps (Alzet, Model 1007D, Durect Corp, CA) were loaded with vehicle (saline) or peptide dissolved in vehicle to allow an infusion rate of 4.5 mg/Kg/day for 2 weeks. Pumps were implanted subcutaneously in anesthetized mice through a small incision between the scapulae [8]. Mice were randomized following MI into three groups. In one group, pumps containing peptide were implanted immediately following MI (acute phase) and removed after 2 weeks. In the second group, pumps containing peptide were implanted at 8 weeks post-MI (chronic phase). The third group pumps containing saline were implanted immediately following MI (acute phase) and removed after 2 weeks. Cardiac function was analyzed in all groups of mice at 10 weeks post-MI.

Pressure-volume loops

Under the same anesthetic regiment, a 1.4 French pressure-conductance catheter (SPR-839, Millar Instruments, Houston TX) was inserted into the right carotid artery to measure baseline arterial pressure, then advanced retrograde into the LV to record baseline hemodynamics in the closed chest configuration with the ARIA Pressure Volume Conductance System (Millar Instruments, Houston, TX). After, a small incision in the diaphragm was made and baseline hemodynamics were obtained followed by transient occlusions of the thoracic vena cava (TVC) to vary venous return. Subsequently, parallel conductance (Vp) was determined by a 10 μl injection of 15% saline into the right femoral vein to establish the offset due to the conductivity of structures external to the blood pool. Data were corrected by Vp based on the volume calibration by submerging the pressure-conductance catheter into heparin treated murine blood in a series of 6 cylindrical holes with known diameters (1.5–4 mm) and 1 cm deep, with a volume of each loop calculated as (slope of 3.213*RVU + intercept of −8.867). All data were analyzed with the PVAN 3.4 software package from Millar Instruments (Houston, TX). Following, mice were euthanized with an overdose of 5% isoflurane, their hearts removed and weighed as previously described [10].

In addition to recording the load-dependent parameters, total peripheral resistance (TPR), was derived by dividing mean arterial pressure by cardiac output. Cardiac index (CI), derived by the ratio of cardiac output divided by body weight. Left ventricle contractility was obtained during transient inferior vena cava occlusions and used to derive the vascular-to-ventricular coupling ratio (A-V relationship). The effective Ea, a term that incorporates arterial load, TPR, and arterial compliance was derived from the ratio of the end systolic pressure over stroke volume. The A-V relationship was the ratio of Ea divided by ESPVR. Cardiac contractile efficiency (CCE), was the ratio of external work over the pressure volume loop area [8,10,11].

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from the apex of the heart with TRIzol (Invitrogen), and used in a one-step RT-PCR reaction with the SYBR Green RNA Amplification kit (Roche Molecular Biochemical, IN) in the LightCycler thermocycler (Roche Diagnostics). The reaction conditions for the reverse transcriptase were 55°C for 15 min, a denaturing step at 95°C for 30 sec, which was followed by four-step PCR amplification for 40-cycles. The second derivative maximum (log linear phase) for each amplification curve was plotted against a standard curve to calculate the amount of product. Samples were normalized against the ribosomal protein, large, P0 (Rplp0), expression to ensure equal loading, as previously described [8]. Primers were designed using GenBank reference sequences and the primer design tool Primer 3. Primer sequences were run against the BLAST database and used for melting curve analysis prior to PCR amplification to ensure single gene specific product amplification.

Statistics

Data are expressed as means ± standard error (SE). Differences in the means were tested using ANOVA followed by Newman-Keuls post-hoc analysis, where appropriate. Cardiac function data were analyzed using 2-way ANOVA to test the influence of two independent variables: infarct and treatment. An all pair wise multiple comparisons using the Holm-Sidak method was used to test for statistical significance (P<0.05).

Results

Since E-domain peptide treatment during MI preserved contractility and prevented hypertrophy, we tested whether treatment initiated during the acute phase post-MI (within 12 hours) would exert similar effects and prevent decompensation into heart failure. In addition, we also tested whether treatment initiated during the chronic phase post-MI (at 8 weeks) could improve cardiac function during decompensation.

The load dependent hemodynamic parameters derived in the closed chest configuration from various groups of MI mice are shown Table 1. Statistical analysis was performed relative to both control untreated mice and untreated 10 wk MI mice. Analysis of the interaction between MGF E-domain peptide treatment and MI showed a statistically significant interaction in some of the measured parameters.

Table 1.

Cardiac function in mice at 10 wks with E-domain peptide treatment initiated during the acute phase or chronic phase post-MI. Pressure-volume loop measurements in the closed chest configuration. HR-heart rate (beats per minute), MAP-mean arterial pressure (mmHg), ESP-end-systolic pressure (mmHg), EDP-end-diastolic pressure (mmHg), ESV-end systolic volume (μl), EDV-end diastolic volume (μl), SV-stroke volume (μl), CO-cardiac output (μl/min), CI-cardiac index (μl/min/g), SW-stroke work (mmHg/μl), dP/dtmax-maximum first derivative of change in systolic pressure with respect to time (mmHg/sec), dP/dtmin-maximum first derivative of change in diastolic pressure with respect to time (mmHg/sec), Tau-Glantz-time constant of fall in ventricular pressure by Glantz method (msec), MaxPower-maximum power (mWatts), PAMP-preload adjusted maximal power (mWatts/μl^2), TPR-total peripheral resistance (mmHg* ml-1* min), Vint-Volume intercept (μl).

| Parameter | Control | 10 wk MI | Acute phase | Chronic phase |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 608 ± 21 | 543 ± 19 | 590 ± 19 | 564 ± 24 |

| MAP | 78.7 ± 2.0 | 56.6 ± 5* | 65.8 ± 4.3 | 72.4 ± 4.5 |

| ESP | 95.4 ± 4.9 | 86 ± 5.3* | 85.4 ± 4.0* | 91 ± 6.0 |

| EDP | 5.5 ± 0.6 | 7 ± 1.3 | 4.7 ± 0.7 | 8.6 ± 1.2 |

| ESV | 26 ± 0.8 | 65.3 ± 4.1* | 51.4 ± 5.0*† | 53.3 ± 3.3*† |

| EDV | 43.9 ± 1.5 | 70.8 ± 4.2* | 60.4 ± 4.0* | 67 ± 3.7* |

| SV | 21.7 ± 0.8 | 10.3 ± 1.0* | 13.1 ± 1.4* | 18.2 ± 1.5†# |

| CO | 13206 ± 600 | 5622 ± 583* | 7725 ± 880* | 10248 ± 938*† |

| CI | 468 ± 25 | 207 ± 17.5* | 268 ± 31.5* | 407 ± 40†# |

| SW | 1708 ± 66 | 679 ± 125* | 805 ± 118* | 1278 ± 165*†# |

| dP/dtmax | 11414 ± 937 | 6752 ± 373* | 7567 ± 599* | 8058 ± 787* |

| dP/dtmin | −10474 ± 757 | −6549 ± 365* | −6576 ± 580* | −7789 ± 610* |

| Tau-G | 7.2 ± 0.4 | 10.6 ± 0.7 | 9.9 ± 1.5 | 8.9 ± 0.6 |

| MaxPower | 12.4 ± 1.4 | 4.5 ± 0.8* | 7.2 ± 1.0* | 8.9 ± 0.8† |

| PAMP | 64.6 ± 6.8 | 10.4 ± 2.6* | 21.6 ± 3.7* | 21.6 ± 3.5* |

| TPR | 6 ± 0.24 | 10.5 ± 1* | 9.7 ± 1.5 | 7.4 ± 0.7 |

| Ea | 4.4 ± 0.25 | 8.7 ± 0.6* | 7.3 ± 0.9* | 5.3 ± 0.57† |

| Vint | 22.4 ± 1.4 | 42.4 ± 4.3* | 38.8 ± 4* | 39.5 ± 2* |

P<0.05 vs. control,

P<0.05 vs. 10 wk MI,

P<0.05 vs. acute phase (n=9 per group).

Overall there was a statistically significant decline in cardiac function in the 10 wk MI group in comparison to control mice. This was reflected in a decline of systolic function, evidence of diastolic dysfunction, dilated ventricles operating with elevated volumes, a decline in stroke volume and cardiac output. This was also accompanied by a decline in mean arterial pressure despite an increase in total peripheral resistance, together showing evidence of decompensation and progression of heart failure (Table 1).

In the MI+E-domain peptide treatment groups, a number of hemodynamic parameters were either attenuated or improved, despite a similar degree of MI, based on dilation at EDV and the volume intercept (Vint). Mice treated with the E-domain peptide during the acute phase post-MI showed attenuation, but overall function was significantly depressed compared to controls. Mean arterial pressure was improved and no longer significantly different than control. Surprisingly, EDP was not elevated despite an increase EDV. There was a tendency for load dependent measurements of cardiac contractility and work (SW, dP/dtmax, MaxPower, PAMP) to be improved relative to 10 wk MI, which may be reflected in a significant lowering of the ESV, plus a tendency to improve SV and CO. Analysis of total peripheral resistance (TPR) and vascular elastance (Ea) derived from the PV loops, were attenuated compared to untreated 10 wk MI mice, indicating an improved ability of arterioles to relieve pressure in the arteries during diastole post-MI in E-domain treated mice.

Mice treated during the chronic phase post-MI showed the greatest signs of improvement in numerous hemodynamic parameters. Most noticeable were measurements of systolic function (ESP, SV, CO), load dependent measurements of cardiac contractility and work (SW, dP/dtmax, MaxPower). Compared to 10-wk MI group these parameters were significantly improved. In addition MAP, TRP and Ea were no different than controls, showing signs of a decreased vascular resistance with E-domain peptide treatment. Interestingly, in both treatment groups there was not a marked improvement in diastolic parameters (dP/dtmin and Tau), with the exception of EDP in the acute treatment group (Table 1).

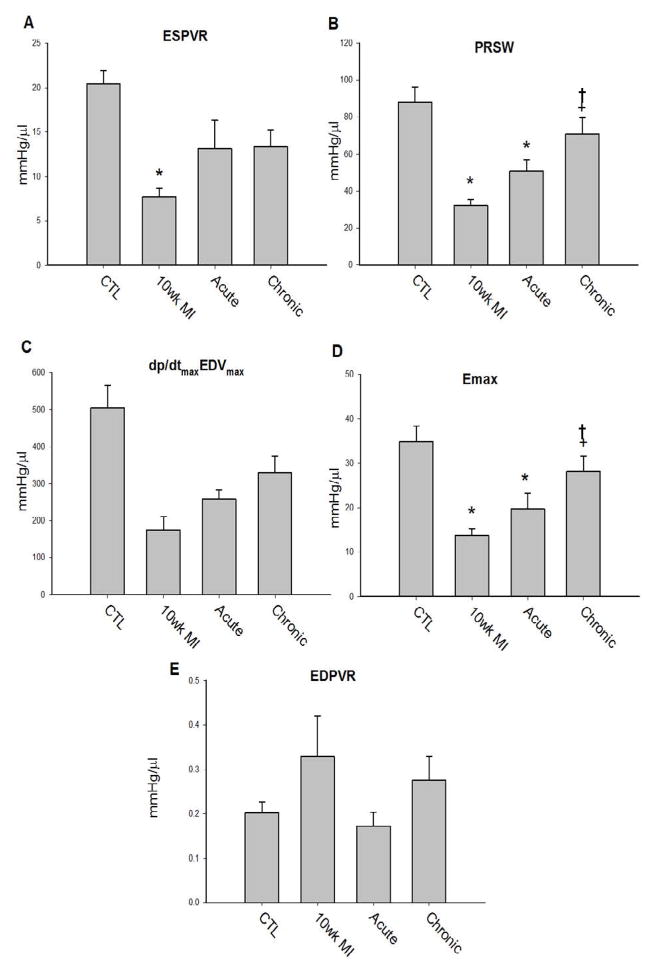

To examine cardiac contractility, load independent hemodynamic parameters were obtained during thoracic vena cava occlusion, and used to derive indexes of cardiac contractility (Figure 1A–1D). Cardiac contractility measured in E-domain peptide treated mice showed signs of improvement compared to untreated 10 wk MI mice. The acute treatment group showed modest improvements, whereas the greatest improvements were noted in the chronic treated groups. Interestingly, delivery of the E-domain peptide at the different times post-MI elicited a different effect on the end diastolic pressure volume relationship (EDPVR), which is a measure of the stiffness or compliance of the ventricle (Figure 1E). Delivery during the acute phase did not result in an increase in stiffness as noted in the untreated 10 wk MI mice, which may explain the decrease EDP despite increased EDV. Delivery during the chronic phase did not decrease the stiffness and in combination with an increase EDV, resulted in elevated EDP noted in these mice.

Figure 1. Cardiac contractility based on pressure-volume loop measurements collected during transient occlusion of thoracic vena cava in 10 wk post-MI mice.

A. ESPVR-end systolic pressure volume relationship

B. EDPVR-end diastolic pressure volume relationship

C. PRSW-preload recruitable stroke work

D. dP/dtMaxEDVMax-maximal dP/dt vs. end diastolic volume

E. Emax-time-varying maximal elastance

Data are means ± S.E.M, n=9, *P<0.05 vs. control and †P<0.05 vs. 10 wk MI

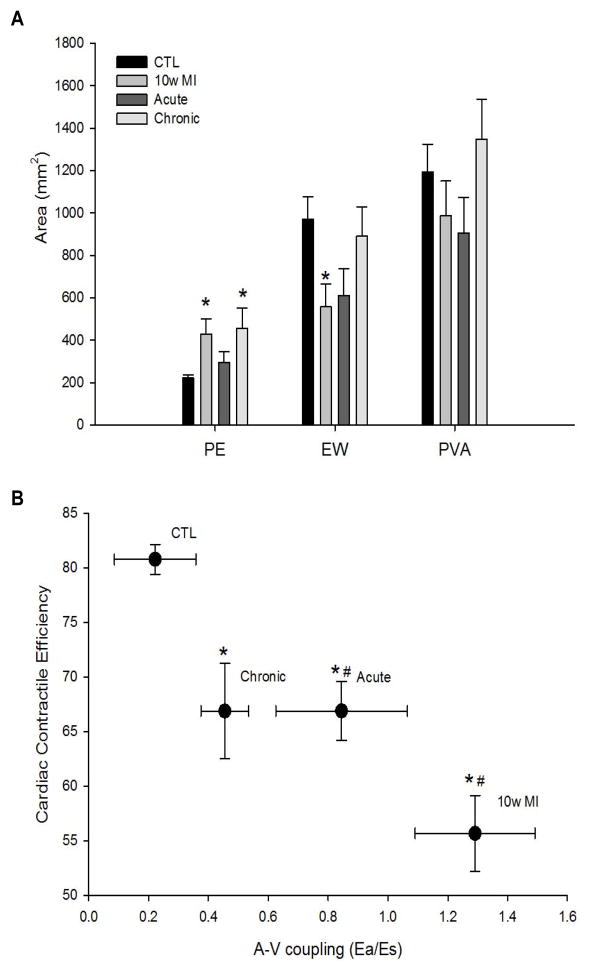

The pressure volume area (PVA), represents the total mechanical energy generated per beat and has been found to correlate linearly with oxygen consumption, which represents the amount of energy metabolized during external work [12–14]. Total mechanical energy is equal to the external stroke work (EW) plus the potential energy (PE) at the end of systole. The external work done by the ventricle is the mechanical energy of contraction transferred to the blood inside the chamber, but only the volume of blood ejected transfers that energy to the arterial system. The rest of the energy is mechanical potential energy, which is dissipated as heat. However, this potential energy can be converted to external work if the ventricle is allowed to eject against a reduced after load [13,15]. Consequently, we examined ventricular mechanoenergics of the untreated and treated groups post-MI (Figure 2A). As a percent of the PVA, the EW was significantly decreased and there was significant increase in PE in the untreated 10 wk MI group compared to controls, (CTL, EW=81%, PE=19%, vs. 10 wk MI, EW=56%, PE=44%), indicating a decrease in cardiac contractile efficiency (Fig 2A). Acute E-domain peptide treatment showed an attenuated response, with the decline in EW and increase in PE being smaller (EW=67%, PE=33%), than 10 wk MI mice. As a percent of the PVA, EW and PE in the chronic peptide treated group was similar to the acute treatment group (EW=66%, PE=34%), but relative to control PE was still significantly higher.

Figure 2.

A. Ventricular mechanoenergetics based on PV loop area in 10 wk post-MI with and without systemic delivery of MGF E-domain peptide.

B. Improvements in cardiovascular function represented by plotting Cardiac Contractile efficiency vs. A-V coupling relationship. Data are means ± S.E.M, n=9, *P<0.05 vs. CTL CCE and #P<0.05 vs. CTL A-V coupling.

The impact of E-domain peptide treatment is further highlighted when cardiovascular function is assessed by the vascular-to-ventricular coupling ratio (Ea/Es), plotted against the contractile efficiency of the ventricle (Figure 2B). A significant decline in CCE and an increase in the Ea/Es ratio in untreated 10 wk MI mice showed these hearts are contracting with low efficiency against an increasing vascular resistance, during decompensation. While both groups of treated mice showed a similar degree of contractile efficiency, the greatest improvements existed in mice treated during the chronic phase post-MI, were a greater degree of vascular unloading occurred. Thus, E-domain peptide treatment during the acute phase delayed the decompensated state, whereas treatment during the chronic phase averted decompensation following MI.

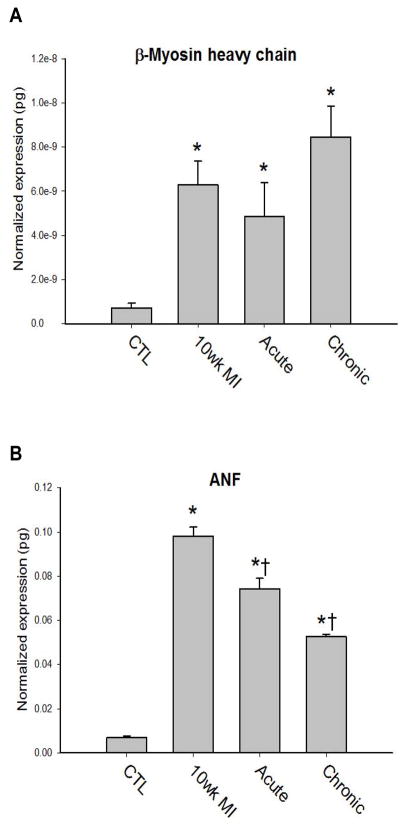

To examine the impact of the improved cardiovascular function with E-domain peptide treatments on cardiac remodeling, cardiac mass was examined. The heart weight to body weight ratio was significantly greater in all three MI groups compared to control and did not differ with E-domain treatment (CTL=5.7±0.2, 10 wk MI=8.7±0.6*, Acute=9.0±0.6*, Chronic=8.1±0.4*, P<0.05). This was not surprising in the chronic treatment group in which treatment was started at 8 weeks post-MI, after the establishment of cardiac hypertrophy. Even though functional improvements occurred in the acute treatment group, the cessation of treatment after 2 weeks was not sufficient to prevent cardiac hypertrophy. Gene expression analysis showed a tendency for α-MHC isoform mRNA expression to increase in all MI groups, but was not statistically different compared to control (data not shown). Expression of the β-MHC isoform which is associated with pathologic remodeling in the rodent heart was significantly increased in all 10 wk MI hearts (Figure 3A). Interestingly, while atrial natriuretic factor (ANF) expression in the ventricle was increased in all the MI groups, there was a significant decrease in the E-domain peptide treated groups compared to the 10 wk MI group (Figure 3B). The greatest decrease in ANF expression occurred in the chronic treatment group, which was significantly lower than the untreated 10 wk MI group.

Figure 3. Quantification of gene expression analysis in the ventricles of in 10 wk post-MI hearts.

A. β-myosin heavy chain isoform expression

B. ANF expression. Data are means ± S.E., n=9, *P<0.05 Vs. Control and †P<0.05 vs. 10 wk MI.

Discussion

The immediate decline in systolic function due to death of the functional myocardial post-MI reduces mean arterial pressure and pulse pressure which reinforces the barorecptor reflex. This initiates the compensatory neurohumoral mechanisms that change autonomic regulation of the cardiovascular system. These bring about an increase in systemic vascular resistance, heart rate and cardiac contractility in order to restore cardiac output and mean arterial pressure through sympathetic stimulation and circulating catecholamine’s. Activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system increases plasma levels of Ang II and aldosterone to regulate blood volume and systemic resistance. However, if prolonged these compensatory mechanisms contribute to the decompensation and progression of heart failure. Consequently these mechanisms are the primary targets for therapeutic management aimed at decreasing arterial pressure, ventricular after load, preload, and limiting cardiac hypertrophy in order to slow the progression of heart failure.

Interest has grown in the growth hormone (GH)/IGF pathway as a potential therapeutic target for ischemic heart disease, due to clinical studies correlating low levels of IGF-1 with increased cardiovascular risk and beneficial effects reported in animal studies with delivery of IGF-1. There is markedly reduced plasma levels of IGF-1 recorded within 24 hours in patients following myocardial infarction and in patients with a higher risk for ischemic heart disease [16,17]. In addition, the lowering of IGF-1 levels is associated with the progression from NYHA Class I-II to Class III-IV in heart failure patients [18]. Significant improvement in cardiac function has been reported following GH administration as a means of increasing systemic IGF-1 levels in animal models of Cardiomyopathy [19–21]. Studies in isolated muscle preparations have shown acute administration of IGF-1 increases contractility and infusion of both IGF-1 and GH produce a positive inotropic effect [22]. However, these favorable results have not translated well in randomized control clinical trials, which have not demonstrated any significant prolonged effects of either IGF-1 or growth hormone administration [23–25]. This may not be too surprising since there is limited bioavailability of IGF-1 once bound to its binding proteins in the circulation and prolonged therapy leads to GH resistance, which represent major therapeutic hurdles. Moreover, these studies speak to the difficulty of defining the actions of IGF-1 produced as a growth factor in tissues, from those associated with systemic levels of IGF-1.

Consequently, awareness has grown with respect to IGF-1 isoform and the action of their unique E-domains has become the focus of understanding IGF-1 isoform function. Previous studies corroborate there are different temporal dynamics in IGF-1 isoform expression in tissues following injury [8,26,27]. Supporting this are a number of studies involving neurologic and cardiac injury models in which delivery of the MGF E-domain peptide has been shown to be beneficial [7–9,28]. However, whether the E-domain of MGF is cleaved and its fate in tissues still needs further clarification. In vitro the IGF-1 prepropeptide is cleaved at a pentabasic-processing motif between the D and E-domains that exists in all isoforms by proprotein convertases [29]. Mutation of this site to prevent cleavage and over-expression of IGF-1Ea and MGF isoforms in skeletal muscle, produced different gene expression profiles compared to mature IGF 1 (with no E-domain attached), suggesting isoform regulation of gene expression occurs via the E-domain regions [30]. In addition, we had previously detected a cleaved fragment of MGF with an E-domain specific antibody in the heart following MI, suggesting the E-domain may have distinct or synergistic actions to IGF-1 [8].

The precise mechanism by which the E-domain regions exert their biological effects are unknown. Synergistic activation of the IGF-1R and downstream signaling has been shown to occur with the E-domains and IGF-1 in vitro [31,32]. It has also been suggested the E-domain may regulate the IGF-1/ECM interaction and modulate IGF-1 availability within the local environment [33]. Together, these studies coalesce around the concept that the E-domains may modulate IGF-1 activity and signaling through its cognate receptor.

There is evidence supporting IGF-1 as a vascular protective factor that may be beneficial in the treatment of chronic heart failure. Vascular relaxation in response to IGF-1 appears to be mediated in part via phosphorylation and activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), to produce more nitric oxide in both endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells [34,35]. Short-term injection of IGF-1 decreases mean arterial pressure in rats, which is inhibited by L-NAME (an NO inhibitor) [36]. Moreover, significant elevation of arterial pressure and peripheral resistance have been recorded in transgenic mouse models of IGF-1 deficiency, suggesting IGF-1 levels play a role in maintaining vascular tone [37,38].

Angiotensin II impairs vascular relaxation and exerts inflammatory, apoptotic, fibrotic, remodeling effects on the vasculature. Acting through the AT1R, Ang II increases the generation of ROS, through activation of the membrane-bound NADPH oxidase complex, which inhibits insulin/IGF-1 signaling through the PI3K/ Akt signaling pathway to activate eNOS [39,40]. These antagonist actions likely contribute to the precipitous decline in cardiovascular function post-MI, which could be limited or prevented with IGF-1 therapies. Our data show the E-domain exerts significant effects on the state of vascular resistance, which was most evident when delivered during the chronic phase post-MI. The reduction in after load on the infarcted heart were reflected in improvements in mean arterial pressure, end systolic volume and stroke volume particularly in the chronically treated MI group. This also contributed to an improvement in the vascular-to-ventricular coupling ratio, indicating an improved mechanoenergetic state of the ventricle during each beat of cardiac cycle. In addition to improvements in functional parameters, improvements were noted in molecular expression profile of ANF within the ventricles of E-domain peptide treated mice. This may have resulted from direct actions of the E-domain peptide on the cardiac myocytes, or could also be in response to the state of after load. Atrial natriuretic factor (ANF) is produced in the atria to an increase blood volume and is involved in the control of blood volume by opposing the function of aldosterone. In the ventricles, ANF has been shown to be expressed in response to stress induced by increase after load and MI [41,42]. While we did not see any effects on maladaptive hypertrophy at these time points, the decline in ANF expression in the ventricle may be a sensitive marker for vascular unloading that occurred with E-domain peptide treatments.

Our data support the notion that the E-domain region of MGF propeptide has biological action and add credence to the use of the E-domain peptide as a means of preventing the decompensation into failure or unloading the already decompensated heart. We propose that by reducing vascular resistance improvements in systolic performance of the dilated heart could serve to mechanically unload the heart, making it a clinically feasible therapeutic strategy. We appreciate the limitations of the present study extend to the use of the permanent coronary ligation model, route of delivery and a single dose of peptide treatment. In addition, the duration of treatment in these experiments was insufficient to prevent/reverse cardiac hypertrophic remodeling, but the improvement in vascular function may have therapeutic implications for slowing the progression of chronic heart failure and acute decompensated heart failure.

Table 2.

Primers sequences used for gene expression analysis.

| Gene | Forward primer | Reverse primer | Genebank Accession Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| α-Myosin | |||

| AAGGTGAAGGCCTACAAGCG | TTTCTGCTGGACAGGTTATTCC | M76601 | |

| heavy chain | |||

| β-Myosin | |||

| AAGGTGAAGGCCTACAAGCG | TTCTGCTTCCACCTAAAGGGC | M74752 | |

| heavy chain | |||

| Atrial | |||

| natriuretic | TGGAGGAGAAGATGCCGGTA | CGAAGCAGCTGGATCTTCGTAG | K02781 |

| factor | |||

| Rplp0 | GGCCCTGCACTCTCGCTTTC | TGCCAGGACGCGCTTGT | NM_007475 |

Acknowledgments

This work was supported National Institutes Health, Heart Lung and Blood Institutes R01 HL090523 (PHG).

References

- 1.Froesch ER, Schmid C, Schwander J, Zapf J. Actions of insulin-like growth factors. Annu Rev Physiol. 1985;47:443–467. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.47.030185.002303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Russell SM, Spencer EM. Local injections of human or rat growth hormone or of purified human somatomedin-C stimulates unilateral tibial epiphyseal growth in hypophysectomized rats. Endocrinology. 1985;116:2563–2567. doi: 10.1210/endo-116-6-2563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vetter U, Zapf J, Heit W, Helbing G, Heinze E, et al. Human fetal and adult chondrocytes. Effect of insulin like growth factors I and II, insulin, and growth hormone on clonal growth. J Clin Invest. 1986;77:1903–1908. doi: 10.1172/JCI112518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shimatsu A, Rotwein P. Mosaic evolution of the insulin-like growth factors. Organization, sequence, and expression of the rat insulin-like growth factor I gene. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:7894–7900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foyt HT, LeRoith D, Roberts CT. Differential association of insulin-like growth factor I mRNA variants with polysomes in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:7300–7305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siegfried JM, Kasprzyk PG, Treston AM, Mulshine JL, Quinn KA, et al. A mitogenic peptide amide encoded within the E peptide domain of the insulin-like growth factorIB prohormone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:8107–8111. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.17.8107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dluzniewska J, Sarnowska A, Beresewicz M, Johnsomn I, Srai SK, et al. A strong neuroprotective effect of the autonomous C-terminal peptide of IGF-1 Ec (MGF) in brain ischemia. FASEB J. 2005;19:1896–1898. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-3786fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mavrommatis E, Shioura KM, Los T, Goldspink PH. The E-domain Region of Mechano-Growth Factor Inhibits Cellular Apoptosis and Preserves Cardiac Function during Myocardial Infarction. Mol Cell Biochem. 2013;381:69–83. doi: 10.1007/s11010-013-1689-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carpenter VA, Matthews KG, Devlin GP, Stuart SP, Jensen JA, et al. Mechano-Growth Factor Ameliorates Loss of Cardiac Function in Acute Myocardial Infarction. Heart Lung Circ. 2008;17:33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2007.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shioura KM, Geenen DL, Goldspink PH. Assessment of Cardiac Function with the Pressure-volume Conductance System Following Myocardial Infarction in Mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H2870–H2877. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00585.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shioura KM, Geenen DL, Goldspink PH. Sex related differences in cardiac function during the progression to heart failure following myocardial infarction in mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;5:R528–34. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90342.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suga H. Total Mechanical Energy of a Ventricle Model and Cardiac Oxygen Consumption. Am J Physiol. 1979;236:H498–H505. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1979.236.3.H498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suga H, Hisano R, Hirata S, Hayashi T, Yamada O, et al. Heart Rate-Independent Energetic and Systolic Pressure-Volume Area in Dog Heart. Am J Physiol. 1983;244:H206–H214. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1983.244.2.H206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takaoka H, Takeuchi M, Odake M, Yokoyama M. Assessment of myocardial oxygen consumption (Vo2) and systolic pressure-volume area (PVA) in human hearts. Eur Heart J. 1992;13:85–90. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/13.suppl_e.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suga H. External Mechanical Work from Relaxing Ventricle. Am J Physiol. 1979;236:H494–H497. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1979.236.3.H494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conti E, Andreotti F, Sciahbasi A, Riccardi P, Marra G, et al. Markedly reduced insulin-like growth factor-1 in the acute phase of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:26–32. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01367-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Juul A, Scheike T, Davidsen M, Gyllenborg J, Jorgensen T. Low serum insulin-like growth factor I is associated with increased risk of ischemic heart disease: a population-based case-control study. Circulation. 2002;106:939–944. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000027563.44593.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watanabe S, Tamura T, Ono K, Horiuchi H, Kimura T, et al. Insulin-like growth factor axis (insulin-like growth factor-I/insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-3) as a prognostic predictor of heart failure: association with adiponectin. Eur J Heart Fail. 2010;12:1214–1222. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfq166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duerr RL, Huang S, Miraliakbar HR, Clark R, Chien KR, et al. Insulin-like growth factor-1 enhances ventricular hypertrophy and function during the onset of experimental cardiac failure. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:619–627. doi: 10.1172/JCI117706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duerr RL, McKirnan MD, Gim RD, Clark RG, Chien KR, et al. Cardiovascular effects of insulin-like growth factor-1 and growth hormone in chronic left ventricular failure in the rat. Circulation. 1996;93:2188–2196. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.12.2188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matthews KG, Devlin GP, Stuart SP, Jensen JA, Doughty RN, et al. Intrapericardial IGF-I improves cardiac function in an ovine model of chronic heart failure. Heart Lung Circ. 2005;14:98–103. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cittadini A, Ishiguro Y, Stromer H, Spindler M, Moses AC, et al. Insulin-like growth factor-1 but not growth hormone augments mammalian myocardial contractility by sensitizing the myofilament to Ca2+ through a wortmannin-sensitive pathway: studies in rat and ferret isolated muscles. Circ Res. 1998;83:50–59. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Isgaard J, Bergh CH, Caidahl K, Lomsky M, Hjalmarson A, et al. A placebo-controlled study of growth hormone in patients with congestive heart failure. Eur Heart J. 1998;19:1704–1711. doi: 10.1053/euhj.1998.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Osterziel JK, Strohm O, Schuler J, Friedrich M, Hanlein D, et al. Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of human recombinant growth hormone in patients with chronic heart failure due to dilated cardiomyopathy. Lancet. 1998;351:1233–1237. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)11329-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Acevedo M, Corbalan R, Chamorro G, Jalil J, Nazzal C, et al. Administration of growth hormone to patients with advanced cardiac heart failure: effects upon left ventricular function, exercise capacity, and neurohormonal status. Int J Cardiol. 2003;87:185–191. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(02)00249-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Philippou A, Papageorgiou E, Bogdanis G, Halapas A, Sourla A, et al. Expression of IGF-1 isoforms after exercise-induced muscle damage in humans: characterization of the MGF E peptide actions in vitro. In Vivo. 2002;23:567–575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hill MA, Goldspink G. Expression and splicing of the insulin-like growth factor gene in rodent muscle is associated with muscle satellite (stem) cell activation following local tissue damage. J Physiol. 2003;549:409–418. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.035832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quesada A, Ogi J, Schultz J, Handforth A. C-terminal mechano-growth factor induces heme oxygenase-1-mediated neuroprotection of SH-SY5Y cells via the protein kinase Cε/Nrf2 pathway. J Neurosci Res. 2011;89:394–405. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Duguay SJ, Milewski WM, Young BD, Nakayama K, Steiner DF. Processing of wild-type and mutant proinsulin-like growth factor-IA by subtilisin-related proprotein convertases. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:6663–6670. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.10.6663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barton ER, DeMeo J, Lei H. The insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I E-peptides are required for isoform-specific gene expression and muscle hypertrophy after local IGF-I production. J Appl Physiol. 2010;108:1069–1076. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01308.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Durzyńska J, Philippou A, Brisson BK, Nguyen-McCarty M, Barton ER. The pro-forms of insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) are predominant in skeletal muscle and alter IGF-I receptor activation. Endocrinology. 2013;154:1215–1224. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brisson BK, Barton ER. Insulin-like growth factor-I E-peptide activity is dependent on the IGF-I receptor. PLoS One. 2012;7:e45588. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hede MS, Salimova E, Piszczek A, Perlas E, Winn N, et al. E-peptides control bioavailability of IGF-1. PLoS One. 2012;7:e51152. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Michell BJ, Griffiths JE, Mitchelhill KI, Rodrigeuz-Crespo I, Tiganis T, et al. The Akt kinase signals directly to endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Curr Biol. 1999;9:845–848. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80371-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Isenovic ER, Meng Y, Divald A, Milivojevic N, Sowers JR. Role of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway in angiotensin and insulin-like growth factor-1 modulation of nitric oxide synthesis in vascular smooth muscle cells. Endocrine. 2002;19:287–292. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:19:3:287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pete G, Hu Y, Walsh M, Sowers J, Dunbar JC. Insulin-like growth factor-I decreases mean blood pressure and selectively increases regional blood flow in normal rats. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1996;213:187–192. doi: 10.3181/00379727-213-44049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lembo G, Rockman HA, Hunter JJ, Steinmetz H, Koch WJ, Ma, et al. Elevated blood pressure and enhanced myocardial contractility in mice with severe IGF-1 deficiency. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:2648–2655. doi: 10.1172/JCI119086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tivesten A, Bollano E, Andersson I, Fitzgerald S, Caidahl K, et al. Liver-derived insulin-like growth factor-I is involved in the regulation of blood pressure in mice. Endocrinology. 2002;143:4235–4242. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Touyz RM, Chen X, Tabet F, Yao G, He G, et al. Expression of a functionally active gp91phox-containing neutrophil-type NAD(P)H oxidase in smooth muscle cells from human resistance arteries: regulation by angiotensin II. Circ Res. 2002;90:1205–1213. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000020404.01971.2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zeng G, Nystrom FH, Ravichandran LV, Cong LN, Kirby M, et al. Roles for insulin receptor, PI-3 kinase and Akt in insulin-signaling pathways related to production of nitric oxide in human vascular endothelial cells. Circulation. 2000;101:1539–1545. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.13.1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rockman HA, Wachhorst SP, Mao L, Ross J., Jr ANG II receptor blockade prevents ventricular hypertrophy and ANF gene expression with pressure overload in mice. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:H2468–H2475. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.266.6.H2468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Loennechen JP, Støylen A, Beisvag V, Wisløff U, Ellingsen O. Regional expression of endothelin-1, ANP, IGF-1, and LV wall stress in the infarcted rat heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;280:H2902–H2910. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.6.H2902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]