Abstract

Whole-cell voltage clamp of mammalian spermatozoa was first achieved in 2006. This technical advance, combined with genetic deletion strategies, makes unambiguous identification of sperm ion channel currents possible. This review summarizes the ion channel currents that have been directly measured in mammalian sperm, and their physiological roles in fertilization. The predominant currents are 1) a Ca2+-selective current requiring expression of the 4 mCatSper genes, and 2) a delayed rectifier K+ current with properties most similar to mSlo3. Intracellular alkalinization activates both channels and induces hyperactivated motility.

Keywords: CatSper, KSper, Ca2+, hyperactivated sperm motility, patch clamp, sperm, Ca2+ channel

Introduction

Mature mammalian spermatozoa are quiescent in the male reproductive tract. Upon ejaculation, they become motile. As they move through the female reproductive tract, they become competent to fertilize the egg. During this period, called capacitation, spermatozoa begin to move progressively, develop hyperactive motility, and their acrosomes can react (Yanagimachi, 1994). Capacitation requires changes in intracellular pH ([pH]i), and concentrations of Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i), and cAMP. The molecular mechanisms responsible for these changes are an active area of research.

[Ca2+]i is increased either as Ca2+ enters the cytoplasm through plasma membrane ion channels, or as Ca2+ is released from intracellular stores. Many Ca2+-permeable channels have been proposed to participate in sperm cell processes (Darszon et al., 2006), including classical voltage-gated Ca2+- (CaV), transient receptor potential- (TRP), and cyclic nucleotide-gated- (CNG) channels. This review summarizes two particular ion currents in sperm cells, CatSper current (ICatSper) and K+ current in spermatozoa (IKSper) that have been directly measured with the recently developed whole-sperm cell patch clamp (Kirichok et al., 2006).

CatSpers1-4

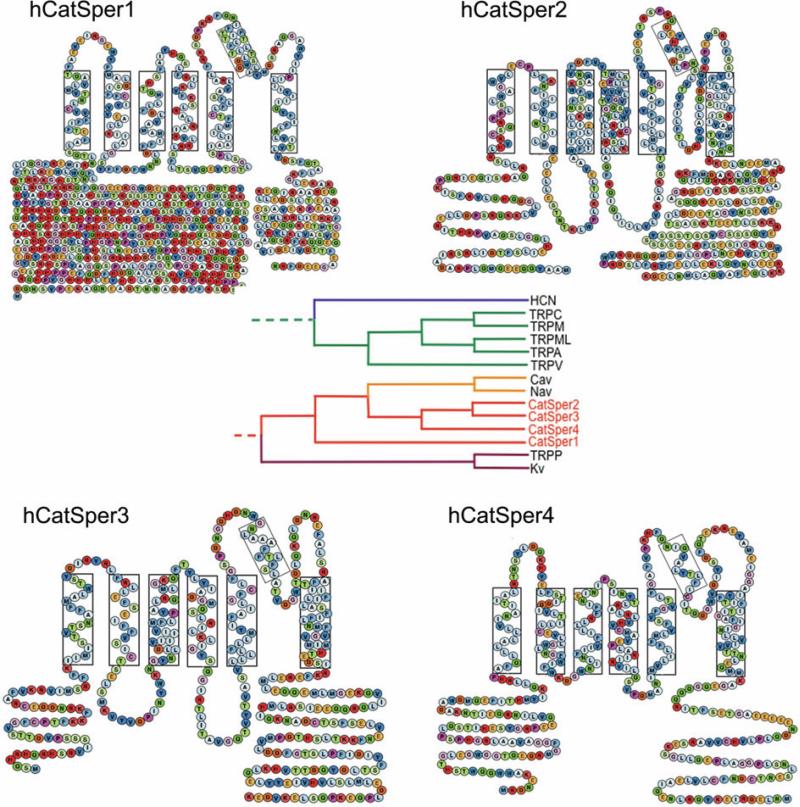

The first member of the CatSper (Cation channel of sperm) family, CatSper1 was detected during searches for sequence homology to the voltage-gated Ca2+-selective channels (CaV1-3) (Ren et al., 2001). The mouse CatSper1 gene is located on mouse chromosome 19 and consists of 12 exons with an open reading frame (ORF) encoding a 686 amino acid protein. CatSper2 was discovered as a sperm cell-specific transcript using a signal peptide trapping method. Mouse chromosome 2 contains the CatSper2 gene, encoding a protein of 588 amino acids in length (Quill et al., 2001). CatSper2 has at least 3 splice variants. The last two members of the family, CatSper3 and CatSper4, were found in database searches (Jin et al., 2005, Lobley et al., 2003, Qi et al., 2007). CatSper3, on mouse chromosomes 13, encodes a 395 amino acid polypeptide, while CatSper 4, on mouse chromosome 4, encodes a 442 amino acid protein. Both CatSper3 and CatSper4 have several potential splice variants. The four CatSper proteins have relatively low sequence identity in the transmembrane regions, ranging from 16 to 22%. Mouse CatSper orthologs have been found in all mammals examined (human (Figure 1), chimpanzee, dog, and rat), in sea squirt (Ciona intestinalis), and sea urchin (Strongylocentrotus purpuratus). CatSpers have not yet been identified in fish (Fugu rubripes and Danio rerio), flies (Drosophila melanogaster), worms (Caenorhaditis elegans), or plants (Arabidopsis thaliana).

Figure 1. Human CatSper1-4 predicted secondary topology.

CatSper1-4 have 6TM with a putative voltage sensor (S1-S4) and a pore (S5-S6) domain. Phylogenetic tree (anchored to NaChBac) is shown in the center. Boxes indicate putative transmembrane segments.

Structural domains of CatSper proteins

The functional channel polypeptides with the closest similarity to CatSpers are the voltage-gated sodium channels (NaVBP) in bacteria and the mammalian CaV family. The predicted topology of all 4 members of the CatSper family consists of cytoplasmic amino- and carboxyl-termini flanking 6 transmembrane (6TM)-spanning segments (S1-S6; Figure 1). Like other voltage-gated channels, these segments are arranged into 2 functionally distinct modules: the voltage sensor (S1-S4) and the pore-forming (S5-P loop-S6) domain. All known CaVs have 4 repeats of the 6TM domain (arising from gene duplication of a single 6TM gene). Ca2+-selectivity is suggested by negatively charged amino acids in the pore consensus sequence ([T/S]x[D/E]xW). CatSpers1-4 each contains a similar conserved motif, TxDxW.

The S1-S4 segments of voltage-gated channels are called the voltage sensor domains (VSDs). The VSD contains 4 to 6 positively charged amino acids (arginine (R)/lysine (K)) spaced at helical turns (3 amino acid intervals) in the S4 segment. Voltage changes move the S4 segment, resulting in conformational changes that open and close (gate) the pore. CatSper1 and CatSper2 contain 4, while CatSper3 and CatSper4 have only 2, R/K residues in the S4 segment. This may be responsible for the reduced voltage dependence of the CatSper heterotetrameric channel.

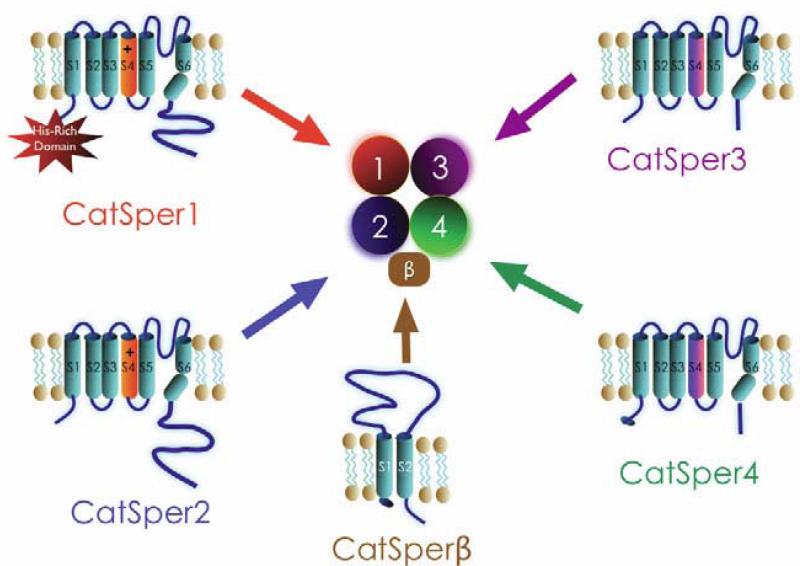

The amino-termini of CatSper2, 3 and 4 are fairly well conserved, but CatSper1's amino terminus is remarkable for its abundance of histidine residues (49/250 amino acids) (Renet al., 2001). The histidine rich amino terminus suggests that CatSper1's amino terminus might be involved in pH regulation of CatSper currents, although other functions are equally plausible. All four of the CatSper proteins contain a coiled-coil domain within their carboxyl-termini, suggesting that heteromultimerization involves these domains. Immunoprecipitation studies performed in CatSper2-null mice provide evidence that stable expression of CatSper1 protein in sperm requires CatSper2 (Carlson et al., 2005). Similarly, studies with CatSper1, 3, and 4 null mice demonstrated that stable CatSper3 and 4 required CatSper1 expression, supporting the heteromultimerization (Figure 2) of these subunits (Qi et al., 2007).

Figure 2. Heterotetramerization of the CatSper channel.

The CatSper complex is formed from CatSpers1-4 protein subunits and an auxiliary subunit. The CatSper auxiliary subunit, CatSperβ, has 2 predicted transmembrane segments, separated by a large extracellular loop (~1000 amino acids).

Tissue distribution and localization of CatSpers

Several laboratories have profiled gene expression of each member of the CatSper family by multi-tissue northern blot analysis. CatSper1, 2, 3 and 4 mRNA was detected exclusively in mouse and human testis (Jin et al., 2005, Qi et al., 2007, Quill et al., 2001, Ren et al., 2001). In situ hybridization studies of CatSper subtypes suggest that CatSpers are differentially transcribed during spermatogenesis. CatSper1 (Ren et al., 2001), CatSper3 and 4 (Jin et al., 2005, Qi et al., 2007, Schultz et al., 2003) transcripts are restricted to the late-stage germ-line cells (spermatids) in testes, while CatSper2 (Quill et al., 2001, Schultz et al., 2003) transcription begins in the early-stage of spermatogenesis (pachytene spermatocytes). Consistent with in situ hybridization studies, real time PCR demonstrated that the CatSper2 transcript was detected in the testis from P8 (postnatal day) mice, whereas transcription of CatSper1 started at P18. CatSper 3 and 4 mRNAs appeared in mouse testis at P15 (Li et al., 2007).

CatSpers1-4 protein localization by antibody staining has proven to be difficult due to lack of specific CatSpers2-4 antibodies. When CatSper subtype null mice are used as controls, CatSpers1-4 proteins are recognized only in testis. Within spermatozoa, CatSpers localize to the principal piece of the flagella (Jin et al., 2005, Qi et al., 2007, Quill et al., 2003, Ren et al., 2001). Genetically deleted mouse controls would be useful in testing the validity of the large number of other ion channel localization studies.

CatSperβ, an auxiliary subunit of the CatSper1 complex

Transgenic mice were made in which CatSper-HA-GFP was inserted on a CatSper1-null mice background (Li et al., 2007). This gene restored fertility in CatSper1 null mice, and the HA and GFP tags allowed for reliable protein purification. Using this strategy, two testis-specific proteins were identified: a heat-shock protein, HSP70-2, and a novel protein subsequently named CatSperβ. The mouse CatSper gene on chromosome 12, encodes an 1109 amino acid protein with its 2 transmembrane segments connected via a large extracellular (~1000 amino acid) domain. CatSperβ homologs are present in mammals and sea squirt (C. intestinalis), and like CatSper1, are absent in C. elegans and D. melanogaster. Immunoprecipitation studies with a native sample (or testicular membrane lysate) demonstrated that CatSper interacts with CatSper1, and like CatSper2-4, is missing in CatSper1-null spermatozoa (Liu et al., 2007). CatSperβ is localized to the principal piece of the sperm flagella. Taken together, these findings suggest that CatSperβ is an auxiliary subunit of the CatSper1 complex. Functional interactions and potential regulation of the CatSper complex by CatSper in spermatozoa are currently being studied.

CatSpers form a Ca2+-selective channel

To examine the basic functional properties of ion channels, they must be tested in voltage clamp under varying ionic conditions. Until recently, transmembrane voltage-clamp recordings in sperm were not possible. Thus, attempts were made to express CatSper proteins in heterologous systems. Despite much effort, heterologous expression of CatSper family members (in various mammalian cell lines and Xenopus oocytes), alone or in combination, failed to yield measurable current. However, initial measurements of Ca2+ influx in sperm cells were carried out using Ca2+-sensitive fluorescent probes. cGMP (Ren et al., 2001) application or depolarization with alkaline K+ solution increased [Ca2+]i, (Carlson et al., 2003, Xia et al., 2007). This inducible Ca2+ increase was abolished in sperm cells from CatSper1- and CatSper2-null mice, indicating that spermatozoa Ca2+ entry required CatSper proteins.

The recent development of patch clamp, by accessing the whole-spermatozoa via the cytoplasmic droplet, finally permitted characterization of CatSper currents. ICatSper is a weakly outwardly rectifying, pH-sensitive, Ca2+-selective current (Kirichok et al., 2006). As for many Ca2+-selective channels, barium (Ba2+) was more permeant than Ca2+ while magnesium (Mg2+) was impermeant. And, as for classical CaV channels, Ca2+ itself participates in Ca2+ selectivity by binding the pore: CatSper conductance was much larger in divalent free (monovalent) solutions.

ICatSper is weakly voltage dependent (Boltzmann slope ~4 compared to ~12 for highly voltage-dependent channels). ICatSper is, however, a very pH-sensitive current. CatSper's g-V curve is significantly shifted to more hyperpolarized potentials by alkaline pH, consistent with increased CatSper current after capacitating conditions that alkalinize the intracellular environment (pH 6.8 to the 7-8 range). An important advantage of employing spermatozoa over other cells is that, in addition to voltage clamp of intact sperm, sperm cell fragments (either the head and midpiece, or midpiece and principal piece), can be patch clamped separately (Kirichok et al., 2006, Qi et al., 2007). Using these methods, ICatSper was specifically localized to the sperm principal piece. ICatSper is absent in spermatozoa from CatSper1-4-null mice (Jin et al., 2007, Kirichok et al., 2006, Qi et al., 2007), while it remains unaltered in sperm cells from wild-type (wt) mice. In other experiments, CatSper current is unaltered in Na+/H+ exchanger-null mice (Qi et al., 2007) when intracellular pH is controlled.

Other Ca2+ permeant channels

A T type CaV current is small (<80 pA), but detectable in spermatocytes (Escoffier et al., 2007, Ren et al., 2001, Santi et al., 1996). The T-type CaV current is also present in CatSper1-null spermatocytes. This current is not detected in spermatocytes from CaV3.2-null mice, and had no effect on spermatogenesis or male fertility (Escoffier et al., 2007). Within the current resolution of patch clamp (~10 pA) and Ca2+ imaging (~100 nM), no purely voltage-gated Ca2+ influx typical of CaV channels was detected in spermatozoa from CatSpers1-4-null mice. Thus, it seems likely that classical CaV currents (CaV1-3, T, P/Q, N, L) are not significant in mature spermatozoa.

Male mice lacking CatSpers1-4 are infertile

All four CatSper genes have now been deleted separately in mice. Homologous recombination was used to delete the first putative transmembrane segment (S1) of CatSper1 (Ren et al., 2001), S1-S3 of CatSper2 (Quill et al., 2003), and the putative pore region of CatSper3 and CatSper4 (Jin et al., 2007, Qi et al., 2007). Testicular histology, epididymal sperm count, and sperm morphology was unaffected in CatSpers1-4-null mice, indicating normal progression of spermatogenesis. Furthermore, there was no difference in the weight, life span, litter size, gross behavior, or mating behavior when wt and homozygous male mutant mice were compared. The striking phenotype of all CatSpers1-4-null mice is complete male infertility; female CatSpers-null mice have normal fertility. To date, some form of (nonsyndromic) male human infertility has been linked to a mutation in the CatSper2 gene (Avidan et al., 2003), but other human CatSper mutations are likely to be found.

Several CaV proteins, as well as TRPC2 and CNGA3, have been detected by antibodies in mouse spermatozoa (Carlson et al., 2003, Darszon et al., 2006). Unfortunately, none of these currents were detected in whole-sperm voltage clamp of mouse epididymal sperm cells. In addition, mice carrying null mutations for CaV1.3 (Platzer et al., 2000), CaV2.2 (Ino et al., 2001), CaV2.3 (Saegusa et al., 2000), CaV3.1 (Kim et al., 2001) and CaV3.2 (Chen et al., 2003), TRPC2 (Stowers et al., 2002) and CNGA3 (Biel et al., 1999) have normal fertility. The CaV1.2 null mutant (Seisenberger et al., 2000) is embryonic lethal and CaV2.1 null pups die ~3-4 weeks after birth (Jun et al., 1999) before fertility can be examined. Thus, CatSper channels are the only known ion channels that specifically affect mammalian male fertility.

The acrosome reaction in CatSper1-null mice

Spermatozoa must release the acrosomal vesicle (remnant of the Golgi apparatus) contained in the head of the sperm upon contact with egg's zona pellucida. The acrosome reaction (AR) releases proteolytic enzymes from the head of the sperm cell that enable penetration of the oocyte extracellular matrix (cumulus cells and zona pellucida) (Yanagimachi, 1994). Although an increase in [Ca2+]i is required for the AR, the source of this Ca2+ is not clear (Publicover et al., 2007). Interestingly, alkaline K+ depolarization and cell-permeable cGMP application induced the AR in CatSper1-null spermatozoa. Alkaline K+ depolarization did not measurably increase [Ca2+]i in these CatSper1-null sperm cells (Xia et al., 2007). These data suggest that the AR does not require Ca2+ entry via plasma membrane ion channels.

Hyperactivated motility requires CatSpers1-4

Upon deposition in the vagina, immotile sperm acquire motility by contact with bicarbonate (HCO3 –). Flagellar motion is symmetrical, low amplitude, and higher frequency when sperm cells are at the entrance of female reproductive tract. In the egg's vicinity, where pH is 7-8, sperm cells develop hyperactivated motility that is characterized by asymmetrical (whip-like), high amplitude, and lower frequency flagellar beating (Ho and Suarez, 2001). Hyperactivated motility, essential for penetration through egg's zona pellucida, requires elevation of Ca2+ in the sperm flagellum (Lindemann and Goltz, 1988).

In vitro fertilization (IVF) studies showed that CatSper1- and CatSper2-null spermatozoa were incapable of fertilizing intact eggs (Quill et al., 2003, Ren et al., 2001). Mutant spermatozoa were able to initiate the fertilization process only after removal of the egg's zona pellucida. Since the acrosome reaction is normal in CatSper1- and CatSper2-null sperm cells, the most likely defect was in motility or hyperactivated motility. Ca2+-independent motility was initially normal in CatSpers1-4-null spermatozoa, but mutant sperm cells failed to develop Ca2+-dependent, hyperactivated motility (Carlson et al., 2005, Carlson et al., 2003, Jin et al., 2007, Qi et al., 2007). Ca2+ entry through CatSper channels is required for sperm hyperactivated motility and enhanced Ca2+ influx induced by alkalinization leads to increased flagellar bending. This result confirms the essential role of Ca2+ ions in sperm cell motility and fertility. Interestingly, CatSpers mutant spermatozoa display a gradual decrease in motility (Jin et al., 2007, Qi et al., 2007) and lower ATP levels compared to wt sperm cells (Xia et al., 2007), suggesting that Ca2+ influx through CatSper channels may regulate other signaling pathways such as Glyceraldehyde 3 phosphate dehydrogenase-S (GAPDS)-dependent glycolysis (Miki et al., 2004).

Thus far, we have discussed the major mammalian inward current in spermatozoa, ICatSper. If ICatSper were the only active ion channel, the membrane potential would be the reversal potential for Ca2+ (Eca; normally ~+150 mV). To balance ICatSper, hyperpolarizing currents must also be present.

K+ current in spermatozoa (IKSper)

Noncapacitated murine spermatozoon resting membrane potential is ~−30 mV. After capacitation, sperm cell hyperpolarize to ~−60 mV (Arnoult et al., 1999, Zeng et al., 1995). Using voltage-sensitive fluorophores, the capacitation-associated hyperpolarization was ascribed to an increase in K+ permeability (Zeng et al., 1995) and block of epithelial sodium channel (Hernandez-Gonzalez et al., 2006).

In whole-sperm patch clamp, a constitutively active, weakly outwardly rectifying K+ current was measured. This current (IKSper) was specifically localized to the principal piece of the sperm flagellum (Navarro et al., 2007). IKSper was reversibly blocked by quinine, EIPA, mibefradil, but clofilium block was irreversible in the time scale of the recordings. Surprisingly, 4-aminopyridine (4-AP), a nonselective KV channel blocker, enhanced IKSper and ICatSper. This effect is a consequence of 4-AP's known alkalinization of the intracellular environment. Spermatozoon intracellular alkalinization, induced by NH4Cl, strongly potentiated IKSper. Average IKSper increased ~8 fold when pHi was elevated from 6 to 8. Thus, IKSper is a pH-sensitive K+ current activated in vivo by intracellular alkalinization.

Murine Slo3 (Schreiber et al., 1998) gene is the most likely candidate responsible for IKSper. mSlo3 is testis-specific and its ion channel properties resemble those of IKsper. mSlo3 is not functionally expressed in mammalian cell lines, but in Xenopus oocytes produces measurable currents potentiated by intracellular alkalinization. Currently, lack of specific antibodies available prevents immunocytochemical identification and localization of mSlo3. Deletion of the Slo3 gene from the murine genome will be required to determine if IKSper is encoded by mSlo3.

IKSper controls the sperm membrane potential

Current clamp experiments reveal the strong pHi dependence of the sperm membrane potential. NH4Cl-induced intracellular alkalinization (pHi increased from 6 to ~8) hyperpolarized the resting membrane potential from ~0 mV to ~−54 mV (Navarro et al., 2007). This hyperpolarization was K+ -dependent and blocked reversibly by quinine, EIPA and BaCl2, and for prolonged durations by clofilium. Together with the lack of other observed currents, these data identify IKSper as the dominant hyperpolarizing conductance within the physiological range. Thus IKSper sets the spermatozoa resting membrane potential.

Integrated Model and Conclusion

The oviduct, where most capacitation occurs, is high in bicarbonate (~40 to 90 mM; (Maas et al., 1977, Tienthai et al., 2004)). Capacitation is defined phenomenologically as the acquisition of the sperm's ability to fertilize an egg, but includes changes in sperm membrane reorganization, an array of tyrosine phosporylation events, increases in [Ca2+]i and membrane hyperpolarization (Yanagimachi, 1994). As a result, sperm cells change from progressive to hyperactivate motility and acquire the ability to acrosome react.

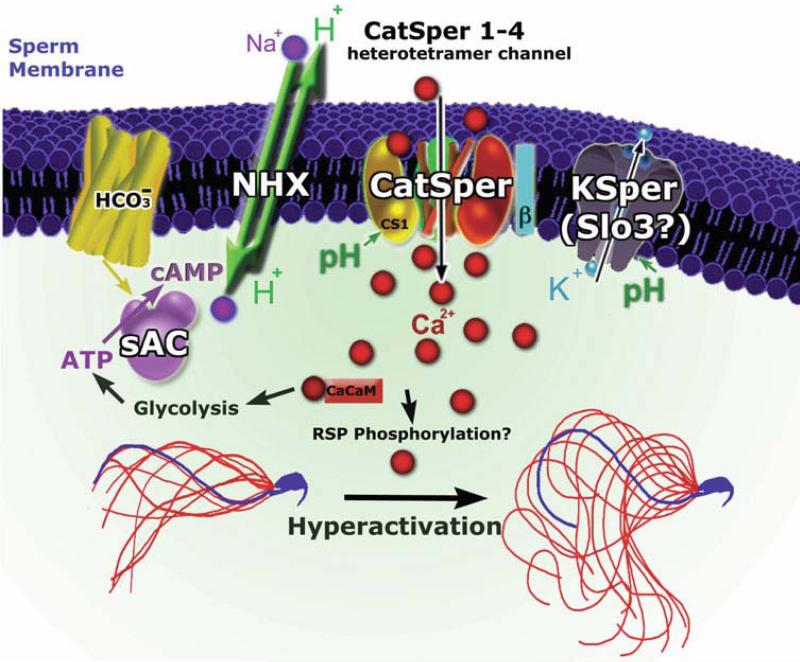

In vitro fertilization (IVF) procedures are possible in part because sperm capacitation can be reproduced in vitro. The essential condition for sperm cell in vitro capacitation is incubation at 37°C in a medium containing Ca2+, 0.4% serum albumin and 20 mM HCO3− (Visconti et al., 1999b, Yanagimachi, 1994). Serum albumin allows cholesterol efflux from the sperm plasma membrane and perhaps induces sperm membrane reorganization (Visconti et al., 1999a). Bicarbonate (Gadella and Van Gestel, 2004) has a profound effect on mammalian sperm function, but the HCO3− entry pathway is not known. HCO3− directly activates the sperm-specific soluble adenylyl cyclase (sAC; Figure 3) (Chen et al., 2000). Activation of sAC increases cAMP levels, which in turn activates protein kinase A (PKA)-dependent phosphorylation cascades, and tyrosine phosphorylation (Visconti et al., 1995a, Visconti et al., 1995b). sAC-null mice are infertile, spermatozoa motility is severely impaired (Esposito et al., 2004), and they lack the pattern typical of tyrosine phosphorylation.

Figure 3. Spermatozoa ion channel activation and regulation integrated model.

HCO3− ions bind and activate soluble adenylyl cyclase (sAC) that in turn increases cAMP synthesis. cAMP activates (direct or indirectly) the sperm specific Na+/H+ exchange (sNHE), thereby increasing intracellular pH. This intracellular alkalinization potently increases ICatSper and IKSper. Alkalinization-mediated potentiation of IKSper hyperpolarizes the membrane potential from ~0 to ~ −50 mV. Ca2+ entry through ICatSper induces a rise in [Ca2+]I, in turn activating Calmodulin and Calmodulin Kinase (CamK). These changes increase flagellar bending and enhance ATP production, thus increasing sperm endurance and hyperactivating sperm motility. Images of normal and hyperactivated motile sperm modified after Carlson, et al., 2005.

Activation of the sperm-specific Na+/H+ exchanger (sNHE), has been postulated to account for sperm intracellular alkalinization. Mice lacking this gene are sterile with severely decreased sperm motility (Wang et al., 2003). sNHE protein contains a voltage sensor domain and a cyclic-nucleotide binding site, suggesting that this protein may be regulated by cAMP and/ or membrane potential. Surprisingly, sNHE-null spermatozoa are deficient in sAC, which together with co-immunoprecipitation experiments indicates that sAC forms a complex with sNHE (Wang et al., 2007). It is still unknown whether cAMP directly or indirectly actives sNHE. It has not yet been technically possible to measure pH in the principal piece where sNHE is localized.

In summary, direct recordings of epididymal sperm cells under whole-cell voltage clamp reveals two primary currents, ICatSper and IKSper. Intracellular alkalinization activates these two specific sperm-ion currents. ICatSper is responsible for the increase in [Ca2+]i during capacitation that enables hyperactivated motility. CatSpers1-4-null mice are infertile and the spermatozoa fail to develop hyperactivated motility. Ca2+ influx through CatSper channels increases flagellar bending in a Ca2+-dependent manner; perhaps (based on work in other cells, e.g. Chlamydamonas) by binding to calmodulin, activation of camodulin kinase, and phosphorylation of radial spoke protein(s) of the axoneme. Also, CatSper1-null spermatozoa have diminished intracellular ATP (Xia et al., 2007), suggesting that CatSper-specific Ca2+ entry may initiate flagellar glycolysis. However, Ca2+ also stimulates enzymes of the Kreb's cycle in mitochondria (see (Kirichok et al., 2004, Rizzuto et al., 2000)). Thus Ca2+ via ICatSper, or combined with Ca2+ from intracellular stores, is likely to be required for the sustained ATP production needed for extended motility and hyperactivation. In contrast, IKSper sets the sperm cell membrane potential and is responsible for the hyperpolarization associated with sperm capacitation. Currently there is no evidence for CaV, Cl−, or cyclic nucleotide-gated currents from direct voltage clamp of mammalian epididymal sperm cells. To play a role in fertilization, these currents would have to be rapidly upregulated after exit from the epididymis. We have not extensively tested for transmitter-gated channels (known or unknown, e.g. chemoattractants), or receptor tyrosine kinase and G protein coupled receptor modulation of ICatSper or IKSper. These studies will be interesting avenues for the future.

Acknowledgement

This article is dedicated to our collaborator, David Garbers, who generously shared his friendship, time, and knowledge.

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health under award number: T32HL007572. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- ARNOULT C, KAZAM IG, VISCONTI PE, KOPF GS, VILLAZ M, FLORMAN HM. Control of the low voltage-activated calcium channel of mouse sperm by egg ZP3 and by membrane hyperpolarization during capacitation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:6757–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AVIDAN N, TAMARY H, DGANY O, CATTAN D, PARIENTE A, THULLIEZ M, BOROT N, MOATI L, BARTHELME A, SHALMON L, et al. CATSPER2, a human autosomal nonsyndromic male infertility gene. Eur J Hum Genet. 2003;11:497–502. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BIEL M, SEELIGER M, PFEIFER A, KOHLER K, GERSTNER A, LUDWIG A, JAISSLE G, FAUSER S, ZRENNER E, HOFMANN F. Selective loss of cone function in mice lacking the cyclic nucleotide-gated channel CNG3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:7553–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CARLSON AE, QUILL TA, WESTENBROEK RE, SCHUH SM, HILLE B, BABCOCK DF. Identical phenotypes of CatSper1 and CatSper2 null sperm. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:32238–44. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501430200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CARLSON AE, WESTENBROEK RE, QUILL T, REN D, CLAPHAM DE, HILLE B, GARBERS DL, BABCOCK DF. CatSper1 required for evoked Ca2+ entry and control of flagellar function in sperm. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:14864–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2536658100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHEN CC, LAMPING KG, NUNO DW, BARRESI R, PROUTY SJ, LAVOIE JL, CRIBBS LL, ENGLAND SK, SIGMUND CD, WEISS RM, et al. Abnormal coronary function in mice deficient in alpha1H T-type Ca2+ channels. Science. 2003;302:1416–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1089268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHEN Y, CANN MJ, LITVIN TN, IOURGENKO V, SINCLAIR ML, LEVIN LR, BUCK J. Soluble adenylyl cyclase as an evolutionarily conserved bicarbonate sensor. Science. 2000;289:625–8. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5479.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DARSZON A, ACEVEDO JJ, GALINDO BE, HERNANDEZ-GONZALEZ EO, NISHIGAKI T, TREVINO CL, WOOD C, BELTRAN C. Sperm channel diversity and functional multiplicity. Reproduction. 2006;131:977–88. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ESCOFFIER J, BOISSEAU S, SERRES C, CHEN CC, KIM D, STAMBOULIAN S, SHIN HS, CAMPBELL KP, DE WAARD M, ARNOULT C. Expression, localization and functions in acrosome reaction and sperm motility of Ca(V)3.1 and Ca(V)3.2 channels in sperm cells: an evaluation from Ca(V)3.1 and Ca(V)3.2 deficient mice. J Cell Physiol. 2007;212:753–63. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ESPOSITO G, JAISWAL BS, XIE F, KRAJNC-FRANKEN MA, ROBBEN TJ, STRIK AM, KUIL C, PHILIPSEN RL, VAN DUIN M, CONTI M, et al. Mice deficient for soluble adenylyl cyclase are infertile because of a severe sperm-motility defect. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:2993–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400050101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GADELLA BM, VAN GESTEL RA. Bicarbonate and its role in mammalian sperm function. Anim Reprod Sci. 2004;82-83:307–19. doi: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2004.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HERNANDEZ-GONZALEZ EO, SOSNIK J, EDWARDS J, ACEVEDO JJ, MENDOZA-LUJAMBIO I, LOPEZ-GONZALEZ I, DEMARCO I, WERTHEIMER E, DARSZON A, VISCONTI PE. Sodium and epithelial sodium channels participate in the regulation of the capacitation-associated hyperpolarization in mouse sperm. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:5623–33. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508172200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HO HC, SUAREZ SS. Hyperactivation of mammalian spermatozoa: function and regulation. Reproduction. 2001;122:519–26. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1220519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- INO M, YOSHINAGA T, WAKAMORI M, MIYAMOTO N, TAKAHASHI E, SONODA J, KAGAYA T, OKI T, NAGASU T, NISHIZAWA Y, et al. Functional disorders of the sympathetic nervous system in mice lacking the alpha 1B subunit (Cav 2.2) of N-type calcium channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:5323–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081089398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JIN J, JIN N, ZHENG H, RO S, TAFOLLA D, SANDERS KM, YAN W. Catsper3 and Catsper4 are essential for sperm hyperactivated motility and male fertility in the mouse. Biol Reprod. 2007;77:37–44. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.107.060186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JIN JL, O'DOHERTY AM, WANG S, ZHENG H, SANDERS KM, YAN W. Catsper3 and catsper4 encode two cation channel-like proteins exclusively expressed in the testis. Biol Reprod. 2005;73:1235–42. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.105.045468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JUN K, PIEDRAS-RENTERIA ES, SMITH SM, WHEELER DB, LEE SB, LEE TG, CHIN H, ADAMS ME, SCHELLER RH, TSIEN RW, et al. Ablation of P/Q-type Ca(2+) channel currents, altered synaptic transmission, and progressive ataxia in mice lacking the alpha(1A)-subunit. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:15245–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.15245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIM D, SONG I, KEUM S, LEE T, JEONG MJ, KIM SS, MCENERY MW, SHIN HS. Lack of the burst firing of thalamocortical relay neurons and resistance to absence seizures in mice lacking alpha(1G) T-type Ca(2+) channels. Neuron. 2001;31:35–45. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00343-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIRICHOK Y, KRAPIVINSKY G, CLAPHAM DE. The mitochondrial calcium uniporter is a highly selective ion channel. Nature. 2004;427:360–4. doi: 10.1038/nature02246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIRICHOK Y, NAVARRO B, CLAPHAM DE. Whole-cell patch-clamp measurements of spermatozoa reveal an alkaline-activated Ca2+ channel. Nature. 2006;439:737–40. doi: 10.1038/nature04417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LI HG, DING XF, LIAO AH, KONG XB, XIONG CL. Expression of CatSper family transcripts in the mouse testis during post-natal development and human ejaculated spermatozoa: relationship to sperm motility. Mol Hum Reprod. 2007;13:299–306. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gam009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LINDEMANN CB, GOLTZ JS. Calcium regulation of flagellar curvature and swimming pattern in triton X-100--extracted rat sperm. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1988;10:420–31. doi: 10.1002/cm.970100309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIU J, XIA J, CHO KH, CLAPHAM DE, REN D. CatSperbeta, a novel transmembrane protein in the CatSper channel complex. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:18945–52. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701083200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOBLEY A, PIERRON V, REYNOLDS L, ALLEN L, MICHALOVICH D. Identification of human and mouse CatSper3 and CatSper4 genes: characterisation of a common interaction domain and evidence for expression in testis. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2003;1:53. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-1-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAAS DH, STOREY BT, MASTROIANNI L., JR. Hydrogen ion and carbon dioxide content of the oviductal fluid of the rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta). Fertil Steril. 1977;28:981–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MIKI K, QU W, GOULDING EH, WILLIS WD, BUNCH DO, STRADER LF, PERREAULT SD, EDDY EM, O'BRIEN DA. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase-S, a sperm-specific glycolytic enzyme, is required for sperm motility and male fertility. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:16501–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407708101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAVARRO B, KIRICHOK Y, CLAPHAM DE. KSper, a pH-sensitive K+ current that controls sperm membrane potential. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:7688–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702018104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PLATZER J, ENGEL J, SCHROTT-FISCHER A, STEPHAN K, BOVA S, CHEN H, ZHENG H, STRIESSNIG J. Congenital deafness and sinoatrial node dysfunction in mice lacking class D L-type Ca2+ channels. Cell. 2000;102:89–97. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PUBLICOVER S, HARPER CV, BARRATT C. [Ca2+]i signalling in sperm--making the most of what you've got. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:235–42. doi: 10.1038/ncb0307-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QI H, MORAN MM, NAVARRO B, CHONG JA, KRAPIVINSKY G, KRAPIVINSKY L, KIRICHOK Y, RAMSEY IS, QUILL TA, CLAPHAM DE. All four CatSper ion channel proteins are required for male fertility and sperm cell hyperactivated motility. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610286104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QUILL TA, REN D, CLAPHAM DE, GARBERS DL. A voltage-gated ion channel expressed specifically in spermatozoa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:12527–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221454998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QUILL TA, SUGDEN SA, ROSSI KL, DOOLITTLE LK, HAMMER RE, GARBERS DL. Hyperactivated sperm motility driven by CatSper2 is required for fertilization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:14869–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2136654100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REN D, NAVARRO B, PEREZ G, JACKSON AC, HSU S, SHI Q, TILLY JL, CLAPHAM DE. A sperm ion channel required for sperm motility and male fertility. Nature. 2001;413:603–9. doi: 10.1038/35098027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RIZZUTO R, BERNARDI P, POZZAN T. Mitochondria as all-round players of the calcium game. J Physiol. 2000;529(Pt 1):37–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00037.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAEGUSA H, KURIHARA T, ZONG S, MINOWA O, KAZUNO A, HAN W, MATSUDA Y, YAMANAKA H, OSANAI M, NODA T, et al. Altered pain responses in mice lacking alpha 1E subunit of the voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:6132–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.100124197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SANTI CM, DARSZON A, HERNANDEZ-CRUZ A. A dihydropyridine-sensitive T-type Ca2+ current is the main Ca2+ current carrier in mouse primary spermatocytes. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:C1583–93. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.271.5.C1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHREIBER M, WEI A, YUAN A, GAUT J, SAITO M, SALKOFF L. Slo3, a novel pH-sensitive K+ channel from mammalian spermatocytes. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:3509–16. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.6.3509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHULTZ N, HAMRA FK, GARBERS DL. A multitude of genes expressed solely in meiotic or postmeiotic spermatogenic cells offers a myriad of contraceptive targets. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:12201–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1635054100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEISENBERGER C, SPECHT V, WELLING A, PLATZER J, PFEIFER A, KUHBANDNER S, STRIESSNIG J, KLUGBAUER N, FEIL R, HOFMANN F. Functional embryonic cardiomyocytes after disruption of the L-type alpha1C (Cav1.2) calcium channel gene in the mouse. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:39193–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006467200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STOWERS L, HOLY TE, MEISTER M, DULAC C, KOENTGES G. Loss of sex discrimination and male-male aggression in mice deficient for TRP2. Science. 2002;295:1493–500. doi: 10.1126/science.1069259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TIENTHAI P, JOHANNISSON A, RODRIGUEZ-MARTINEZ H. Sperm capacitation in the porcine oviduct. Anim Reprod Sci. 2004;80:131–46. doi: 10.1016/S0378-4320(03)00134-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VISCONTI PE, BAILEY JL, MOORE GD, PAN D, OLDS-CLARKE P, KOPF GS. Capacitation of mouse spermatozoa. I. Correlation between the capacitation state and protein tyrosine phosphorylation. Development. 1995a;121:1129–37. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.4.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VISCONTI PE, MOORE GD, BAILEY JL, LECLERC P, CONNORS SA, PAN D, OLDS-CLARKE P, KOPF GS. Capacitation of mouse spermatozoa. II. Protein tyrosine phosphorylation and capacitation are regulated by a cAMP-dependent pathway. Development. 1995b;121:1139–50. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.4.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VISCONTI PE, NING X, FORNES MW, ALVAREZ JG, STEIN P, CONNORS SA, KOPF GS. Cholesterol efflux-mediated signal transduction in mammalian sperm: cholesterol release signals an increase in protein tyrosine phosphorylation during mouse sperm capacitation. Dev Biol. 1999a;214:429–43. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VISCONTI PE, STEWART-SAVAGE J, BLASCO A, BATTAGLIA L, MIRANDA P, KOPF GS, TEZON JG. Roles of bicarbonate, cAMP, and protein tyrosine phosphorylation on capacitation and the spontaneous acrosome reaction of hamster sperm. Biol Reprod. 1999b;61:76–84. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod61.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANG D, HU J, BOBULESCU IA, QUILL TA, MCLEROY P, MOE OW, GARBERS DL. A sperm-specific Na+/H+ exchanger (sNHE) is critical for expression and in vivo bicarbonate regulation of the soluble adenylyl cyclase (sAC). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:9325–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611296104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANG D, KING SM, QUILL TA, DOOLITTLE LK, GARBERS DL. A new sperm-specific Na+/H+ exchanger required for sperm motility and fertility. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:1117–22. doi: 10.1038/ncb1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- XIA J, REIGADA D, MITCHELL CH, REN D. CATSPER channel-mediated Ca2+ entry into mouse sperm triggers a tail-to-head propagation. Biol Reprod. 2007;77:551–9. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.107.061358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YANAGIMACHI R. The Physiology of Reproduction. New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- ZENG Y, CLARK EN, FLORMAN HM. Sperm membrane potential: hyperpolarization during capacitation regulates zona pellucida-dependent acrosomal secretion. Dev Biol. 1995;171:554–63. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]