Abstract

Waterpipe smoking is becoming increasingly popular worldwide. Research has shown that cigarette smoke, in addition to hundreds of carcinogenic and otherwise toxic compounds, may also contain compounds of microbiological origin. In the present study we analyzed waterpipe smoke for some microbial compounds. Both of the two markers studied, viz 3-hydroxy fatty acids of bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and ergosterol of fungal biomass, were found in waterpipe tobacco, in amounts similar as previously found in cigarette tobacco, and in smoke. Waterpipe mainstream smoke contained on average 1800 pmol LPS and 84.4 ng ergosterol produced per session. An average concentration of 2.8 pmol/m3 of LPS was found in second hand smoke during a 1-2-h waterpipe smoking session while ergosterol was not detected; corresponding concentrations from smoking five cigarettes were 22.2 pmol/m3 of LPS and 87.5 ng/m3 of ergosterol. This is the first time that waterpipe smoking has been shown to create a bioaerosol. In the present study we also found that waterpipe smoking generated several polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, carbon monoxide, and high fraction of small (<200 nm) particles that may have adverse effects on human health upon inhalation.

Keywords: Lipopolysaccharide, Ergosterol, Total particulate matter (TPM), Tobacco, Waterpipe, Lung deposition

1. Introduction

Cigarette tobacco contains large amounts of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria as well as molds (Larsson et al., 2008). Also cigarette smoke is rich in microbial compounds. The presence of endotoxin, viz the biologically active lipopolysaccharide (LPS) of Gram-negative bacteria, in cigarette smoke was demonstrated already in 1999 (Hasday et al., 1999). This finding was important since endotoxin is a strong pro-inflammatory agent. Later, gas chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (GC-MSMS) was used to identify LPS and fungal biomass marker ergosterol in mainstream (MS) smoke (Larsson et al., 2004; Larsson et al., 2008). A positive relationship was found between the amounts of LPS and ergosterol in the tobacco of a studied cigarette and the amounts of the same substances in MS smoke (Larsson et al., 2008). A positive relationship was also found in second hand (SH) smoke between the number of cigarettes smoked indoors over a certain period of time and air concentrations of ergosterol and LPS (Sebastian et al., 2006). Sidestream (SS) smoke contains much fewer quantities of microbiological compounds than MS smoke probably due to thermal degradation (Larsson et al., 2012). While the microbial compounds in the smoke stem from the microbes in the tobacco, other chemicals in the smoke are largely formed by combustion during the smoking. These chemicals include for example carbon monoxide (CO) and numerous hazardous organic compounds (Shihadeh et al., 2012).

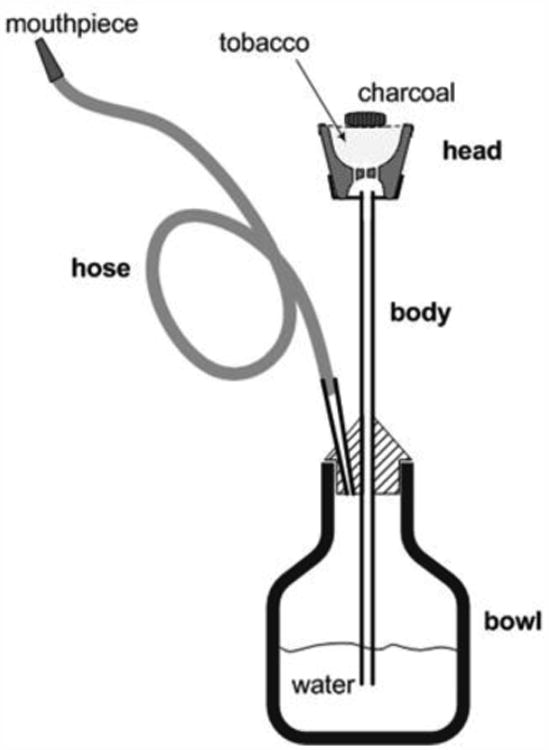

Waterpipe smoking (see Figure 1) is considered by many tobacco users as being less harmful than cigarette smoking and has gained wide popularity in Europe and the US (Akl et al., 2011). However, the available data show that smoking waterpipe results in SH smoke emissions of appreciable amounts e.g. of ultrafine particles, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), and aldehydes (Daher et al., 2010). Several of the PAHs in waterpipe smoke are carcinogenic (Sepetdjian et al., 2008). Research has also shown that waterpipe MS smoke, even after having passed the water in the pipe bowl, contains high levels of CO, toxic metals as well as carcinogenic compounds (Sajid et al., 1993; Sepetdjian et al., 2013; Shihadeh et al., 2012), and that toxicants are effectively delivered to the bloodstream (Blank et al., 2011) inducing measurable acute health effects (e.g. changes in heart rate variability (Cobb et al., 2012)). However, there have been no studies on the possible presence of microbe-derived substances in waterpipe tobacco and smoke. Because of the significantly lower temperature of the tobacco in a waterpipe compared to a cigarette (Shihadeh, 2003), microbial substances may be more efficiently transferred intact to the smoke from the tobacco.

Fig. 1.

A narghile waterpipe. The waterpipe consists of a head, body, water bowl, and hose. A moistened, flavored tobacco mixture is placed in the head and covered with a piece of perforated aluminum foil. Burning charcoal is placed on top of the aluminum foil to provide the heat needed to generate the smoke. When a user takes a puff, air and hot charcoal fumes are drawn through the tobacco mixture, and eventually through the water bubbler, hose and mouthpiece. Between puffs, sidestream toxicants are emitted directly from the head to the surrounding environment. Similar quantities of charcoal and tobacco mixture are consumed in a typical 1 hour café use session (Figure adapted from Monzer et al. (2008)).

The aim of the present study was to measure some selected microbial compounds in waterpipe tobacco and smoke. LPS and ergosterol were determined in tobacco and in machine generated SS and MS smoke. SH smoke was studied following smoking in an aerosol chamber. Waterpipe smoke was also analysed for PAHs, CO, particle size, and particle concentration. Cigarette smoke was used for comparison. Both types of smoke were characterized with regard to particle size distribution and mass concentration in order to estimate and compare the exposure and deposited dose in the respiratory tract.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Waterpipe tobacco

Two 100 g packages of eight brands of waterpipe tobacco were purchased at retail outlets in Beirut during the month of April, 2011. For each brand, the contents of the two packages were homogenized and approximately 100 g were sampled and ground manually using a mortar and a pestle. Two grams from each resulting mixture were then placed in a sterile, sealed plastic tube. The 16 tubes were coded for blinding and sent along with empty tubes to Lund University for analysis.

2.2. Machine generated mainstream and sidestream smoke

MS and SS waterpipe smoke were machine-generated at the American University of Beirut following the 171-puff Beirut Protocol (Katurji et al., 2010; Shihadeh, 2003). In brief, 10 g of “Two-Apples” Nakhla™ waterpipe tobacco mixture were loaded in the waterpipe head and the head was covered by an aluminum sheet which was then perforated using a standard hole-punch pattern. The waterpipe was of the design described in Shihadeh (2003) and the leather waterpipe hose had an infiltration rate of 1.6 liters per min (LPM) when measured as described elsewhere (Saleh and Shihadeh, 2008). A single lit 33 mm cylindrical charcoal briquette (5–6 g typical weight) for waterpipe smoking (Three Kings™, Netherlands) was placed on the top of the head at the start of the smoking session; an additional ½ briquette was added at the 105th puff. MS smoke was drawn by the smoking machine through four parallel 47 mm glass fiber filters (Gelman Type A/E), which were changed periodically (3-5 filter changes per session) during a given smoking session to avoid breakthrough overload. The filters were arranged in a parallel flow configuration using a 4-way aerosol splitter (TSI, Inc.) that was attached to the mouthpiece of the waterpipe (see Shihadeh et al. (2012) for details). To collect SS smoke, the waterpipe head was sealed in a 10 L cubical flow enclosure during smoking. Diluted SS smoke emissions were drawn at 16.7 LPM through a 47 mm glass fiber filter installed at the top of the enclosure, while HEPA-filtered makeup air entered through a flow port located on one side. All filters were conditioned for at least 72 hours at 22°C and 60% humidity prior pre- and post-weighing to determine collected total particulate matter (TPM), and then sent to Lund University for analysis. Field blanks were included and all samples were coded for blinding. Filters from 10 replicate sessions were analyzed. In addition to collecting MS and SS smoke TPM for ergosterol and LPS analyses, CO yields were measured in the MS smoke as in Shihadeh and Saleh (2005).

In separate experiments (n=4) MS smoke was collected as described above. Aliquots (50-ml) of the water in the waterpipe bowl (850-ml) were taken both before and after each smoking session, freeze-dried, and sent to Lund for analysis.

2.3. Second hand smoke

The experiments were conducted in an 21.6 m3 exposure chamber at the Aerosol Laboratory at Lund University. The chamber's interior surfaces are made of stainless steel, and there is a 0.8 m2 glass window in one of the walls. Detailed description is given elsewhere (Pagels et al., 2009). In the present study the air supplied to the chamber first passed through an air conditioning unit which allowed control of the air temperature and relative humidity. Then the supply air, before entering the chamber, passed through an activated carbon filter to remove volatile organic compounds and an ultra-low penetration air (ULPA) filter for particle removal. Air to the chamber was supplied from the roof while the exhaust was positioned in the opposite corner from the supply at a height of 0.5 m from the floor. The air exchange rate was set to 0.5 h-1. A positive pressure difference of about 10 Pa between the chamber and surroundings was established to eliminate penetration of particles from the outside. To ensure complete mixing, a fan was operating in the chamber.

In three experiments comprising waterpipe smoking, a portion of tobacco (“Two-Apples” Nakhla™ approximately 10 g) was placed in the waterpipe head and covered by perforated aluminium foil. One liter of distilled water was added in the waterpipe bowl. Thereafter, the smoker entered the chamber and waited for approximately 10 minutes for removal of background particles and stabilization of air pressure. Then the smoker placed charcoal (quick lighting charcoal briquette, approximately 6-7 g) at the top of the waterpipe head, and began smoking. When the coal was finished, a new briquette was lit and added to the head. The smoking session lasted 120 (1st experiment) and 60 min (2nd and 3rd) with approximately 1-2 puffs/min.

For comparison, three experiments comprised of smoking of five cigarettes (Marlboro Red) during 60 min with approximately 8-14 2-s puffs per cigarette were conducted in the same chamber, with the same types of sampling and analyses. Notably, five cigarettes contain approximately the same amount of tobacco as the amount used in each waterpipe smoking session. Because different individuals inhale different amounts of smoke each waterpipe and cigarette smoking session involved a different smoker.

Smoke particles were collected on 37 mm polycarbonate filters (0.8 μm pore size, Millipore, Ireland) used with open face filter cassettes. Filters used for gravimetric analyses (pre- and post-weighted) were kept in the freezer until analysis. CO was measured by using a CO9912C instrument (Testoon, France; accuracy ± 5%).

2.4. Chemical analysis of tobacco and smoke

Samples were stored in a freezer (-20 °C) until analysis.

The homogenized tobacco samples were weighed (approximately 100-150 mg used for each analysis) and dried in a desiccator. The freeze-dried water samples were dissolved in 2-ml portion of distilled (endotoxin free, Endosafe®, Charles River Laboratories, USA) water and 100-μl portions were used for determination of endotoxin activity by using the Limulus test. Residues were again freeze-dried and analyzed by GC-MSMS for LPS by using 3-hydroxy fatty acids of 10-18 carbon chain lengths as chemical markers. Samples were subjected to alkaline hydrolysis for analysis of ergosterol and to acid methanolysis for analysis of LPS. The limits of detection for the ergosterol and 3-hydroxy fatty acid derivatives are 25 and 2 pg respectively (injected amounts) (Saraf and Larsson, 1996). The entire collected filter and water samples were used for the analyses, but only a 1/20th fraction of the tobacco hydrolysate (ergosterol) and a 1/10th fraction of the tobacco methanolysate (LPS) were used for silylation. GC-MSMS analysis of ergosterol and 3-hydroxy fatty acids were performed as described elsewhere (Larsson et al. 2008). Briefly, the samples (filters, tobacco, and freeze-dried water) were heated in methanolic HCl (to release LPS-bound 3-hydroxy fatty acids) or methanolic NaOH (to release ergosterol) thereafter the analytes were silylated.

Two filters each from the waterpipe and cigarette SH smoke sessions (n=2) were placed in airtight Analyslide Petri Dishes (Pall, USA) and sent to Gothenburg (transportation time < 24 h) for analysis of PAHs (Kliucininkas et al., 2011). The limits of quantification (LOQ) for the different PAHs are provided in Table 3; the recovery varies between 70 and 120% (unpublished results).

Table 3. Average PAHs (ng/m3) concentrations found in waterpipe (n=2) and cigarettes (n=2) second hand smoke; limit of quantification (LOQ, ng/m3).

| PAH | Waterpipe smoke | Cigarette smoke | LOQ |

|---|---|---|---|

| naphthalene | nd | nd | <0.550 |

| acenaphthylene | nd | nd | <0.120 |

| acenaphthene | nd | nd | <0.075 |

| fluorene | nd | nd | <0.450 |

| phenanthrene | nd | nd | <0.055 |

| anthracene | nd | nd | <0.015 |

| fluoranthene | nd | 2.29 | <0.034 |

| pyrene | 0.31 | 3.25 | <0.060 |

| benzo(a)anthracene | 0.26 | 5.74 | <0.013 |

| chrysene | 0.49 | 10.69 | <0.041 |

| benzo(b)fluoranthene | 1.76 | 2.82 | <0.020 |

| benzo(k)fluoranthene | 0.90 | 1.36 | <0.028 |

| benzo(a)pyrene | 1.52 | 2.84 | <0.016 |

| indeno(1.2.3-c.d)pyrene | 2.40 | 1.67 | <0.050 |

| dibenzo(a.h)anthracene | 0.16 | 0.23 | <0.050 |

| benzo(g.h.i)perylene | 3.85 | 1.19 | <0.008 |

| Total PAHs | 11.65 | 28.64 | - |

nd – not detected

2.5. Physical analysis of second hand smoke particles

Particle number size distributions were measured in the range 10-650 nm with a scanning mobility particle sizer (SMPS) consisting of a condensation particle counter (CPC, TSI Inc., model 3010, USA) and a differential mobility analyzer (DMA, Vienna type, 0.28 m effective length). Scan time was set to 90 s. A correction for smearing of the CPC signal was included (Collins et al., 2002).

Online measurement of the mass concentration was made with a tapered element oscillating microbalance mass concentration (TEOM series 1400A, Ruprecht & Patashnik Inc., filter temperature 30 °C). A cyclone was connected to the inlet for measurement of the particle fraction below 1 μm (PM1), which includes essentially all the smoke particles.

The effective density, ρ(dp), of the particles was measured during the active smoking period with an aerosol particle mass analyzer (APM, model 3600, Kanomax, Japan) in the size range 70-420 nm as described by McMurry et al. (2002) and Rissler et al. (2014). The APM system was calibrated by 100 nm polystyrene latex spheres (Duke Scientific Corp., USA). The measured data were well described with a single effective density for each particle size. In addition to the mass concentration directly measured by the TEOM, the mass concentration, Cmass, was also calculated from the particle number size distribution and the effective densities:

| (1) |

Here, Cnumber (dp) is the size dependent number concentration of particles and ρ(dp) the size dependent effective density.

2.6. Calculation of the dose of second hand smoke particles to the lung

The respiratory tract deposition of the smoke was estimated based on the Multiple Path Particle Dosimetry (MPPD) model (version 2.11; Chemical Industry Institute of Toxicology, Research Triangle Park, NC). The calculated deposition fractions were averages for men and women breathing relaxed through the nose (men: 12 breaths/min and 0.75 L tidal volume; women: 14 breaths/min and 0.464 L tidal volume). The predicted deposition pattern was adjusted based on the hygroscopic properties of for low temperature combustion of biomass fuel as described by Löndahl et al. (2008). The measured effective densities were used to derive the deposited dose by mass to the respiratory tract.

3. Results

3.1. Waterpipe tobacco

Two portions of each homogenized tobacco samples were analyzed. The 16 tobacco samples contained a mean of 0.467 (SD 0.203) ng ergosterol/mg and 1.85 (SD 0.33) pmol LPS/mg. There was no correlation between the amounts of ergosterol and LPS in the studied samples.

3.2. Mainstream and sidestream smoke

LPS was detected in all of the MS and SS smoke machine-generated samples (n=10) whereas ergosterol was found in all MS smoke and in 5 of the SS smoke samples (Table 1). A mean of 1800 pmol of LPS and 84.4 ng of ergosterol was found in MS smoke per smoking session. There was approximately 100 times more LPS and ergosterol in MS smoke than in SS smoke. There was a strong correlation between MS TPM and MS LPS (R2=0.6593) but not with MS ergosterol.

Table 1. Amounts (mean) of carbon monoxide, total particulate matter, ergosterol, and LPS in MS and SS smoke per machine waterpipe smoking session (n=10). Numbers within brackets denote standard deviation of the mean.

| Mainstream | Sidestream | |

|---|---|---|

| CO (mg) | 254 (29) | na* |

| TPM (mg) | 1870 (310) | na* |

| Ergosterol (ng) | 84.4 (51.2) | 0.64 (0.82) |

| LPS (pmol) | 1800 (300) | 17.0 (4.7) |

na - not analyzed

In the separate experiments MS smoke trapped on the filters contained 724.4 (58.5 SD) pmol of LPS while 882 (177) pmol were trapped in the water. The concentration of endotoxin in the water as measured by Limulus test decreased from 30 endotoxin units (EU)/ml before smoking to 6 EU/ml after smoking. We note that these separate experiments were executed using a different batch of tobacco than the earlier experiments, and that the LPS contained in the tobacco may have been considerably different than the earlier batch. The primary purpose of these experiments was to determine whether the water bowl trapped a significant fraction of the LPS in the smoke. We note that the apparent trapping efficiency of circa 50% of the LPS includes both LPS that may have been absorbed from the smoke, as well as any LPS that may have directly dripped into the water bowl with the heated glycerol mixture that typically flows down the inner surfaces of the waterpipe body (see Figure 1) during smoking.

3.3. Second hand smoke

SH waterpipe smoke contained 2.8 pmol of LPS/m3 whereas the amount of ergosterol was below the detection limit. SH smoke of the five cigarettes contained 87.5 ng of ergosterol and 22.2 pmol of LPS/m3 (Table 2). After the waterpipe smoking sessions the water contained 3 times more LPS (1.64% of the total amount of LPS in the tobacco used in the experiment) than before smoking.

Table 2.

Amounts of ergosterol and LPS in SH waterpipe and cigarette smoke (per five smoked cigarettes) and trapped in the water in the waterpipe bowl during each smoking session (n=3), respectively. Numbers within brackets denote standard deviation of the mean.

| Sample | Ergosterol ng | LPS pmol |

|---|---|---|

| Waterpipe smoke | nd | 2.8 (0.7)/m3 |

| Cigarette smoke | 87.5 (28.0)/m3 | 22.2 (4.3)/m3 |

| Trapped in water | na | 273.6 (30.2)/l |

nd - not detected

na - not analyzed

Of the 16 targeted PAHs, naphthalene, acenaphthylene, acenaphthene, fluorene, phenanthrene, and anthracene were either absent or present in concentrations under the detection limit. Chrysene dominated in the cigarette smoke followed by benzo(a)anthracene and pyrene whereas benzo(g,h,i)perylene dominated in the waterpipe smoke followed by indeno(1,2,3-c,d)pyrene and benzo(b)fluoranthene (see Figure 2 and Table 3). The average sum of PAHs found in waterpipe SH smoke (11.6 ng/m3) was less than half of the amounts found in cigarette SH smoke (28.4 ng/m3),

Fig. 2. Average ambient air PAHs concentrations in SH smoke for waterpipe (n=2) and cigarette smoking (n=2) per 5 cigarettes.

The mean particle number size distributions for the triple waterpipe and cigarette smoke experiments are shown in Figure 3. As illustrated in Figure 4 the total particle number concentrations varied over time but were similar for the two types of smoke. However, the cigarette smoke particles were generally larger in size and thus had a higher total mass. The count mean diameter (CMD) of the cigarette smoke particles was 130 nm with a geometric standard deviation (σg) of 2.0. The size distribution of the particles emitted from waterpipe smoking was bimodal, with one peak below the measured size range (< 10 nm) and a second peak at 65 nm. The average particle number concentration in the aerosol chamber over the entire measurement period was 1.5 · 105 and 1.9 · 105 cm-3 for the cigarette and waterpipe smoke, respectively. However, during the smoking the number concentrations occasionally peaked to levels 4 to 7 times higher.

Fig. 3. Mean particle number size distributions presented as average of the three conducted experiments for cigarette and waterpipe SH smoke (mean ± SD).

Fig. 4. Variation of total particle number concentration over time in one conducted SH smoke experiment.

The mean mass concentrations (measured by the TEOM) were 1003 and 100 μg/m3 for the cigarette and waterpipe smoke particles, respectively (Table 4). The variation of mass concentration over time, in one conducted experiment, is illustrated in Figure 5.

Table 4. Time-averaged chamber particle number and mass concentrations during waterpipe and cigarette smoking (n=3). Number within brackets denote standard deviation.

| Concentration | Unit | Cigarette smoke | Waterpipe smoke |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean number | #/cm3 | 1.5 · 105 (± 9.2 · 103) | 1.9 · 105 (± 5.2 · 104) |

| Median number | #/cm3 | 7.0 · 104 (± 1.4 · 104) | 8.7 · 104 (± 6.8 · 104) |

| Maximum number | #/cm3 | 6.2 · 105 | 1.3 · 106 |

| Mean mass* | μg/m3 | 1003 (± 99) | 100 (± 57) |

| Median mass* | μg/m3 | 762 (± 58) | 38 (± 37) |

| Maximum mass* | μg/m3 | 3488 | 1639 |

From TEOM measurements

Fig. 5. Instantaneous SH smoke particle mass concentration as measured by a tapered element oscillating microbalance (TEOM) in one of the three conducted experiments.

From the measured data a density of 1.25 g cm-3 was estimated for particles up to 80 nm in diameter (see Figure 6). Above this particle size a power-law function with the exponent -0.15 (corresponding to a mass-mobility exponent of 2.85) was fitted to the measured effective densities. For instance, the density of 100 nm particles was 1.20 g cm-3 and of 400 nm particles 0.98 g cm-3. Mass concentrations calculated from the number size distributions (equation 1) were 549 μg/m3 for the cigarette smoke and 74 μg/m3. This is a lower mass concentration than measured by the TEOM. However, the studied size range for the TEOM was larger (< 1 μm) than for the size distribution measurement (0.01-0.65 μm). This is likely to explain most of the difference, since the large particles contribute substantially to the mass.

Fig. 6. The effective density of the SH smoke particles measured by an aerosol particle mass analyzer.

An estimate of the respiratory tract deposition from exposure to the SH smoke is shown in Figure 7. The deposited mass to the respiratory tract is approximate for exposure during one hour to 5 cigarettes or one waterpipe session of 60-120 min. The deposited dose is higher for the cigarettes due to the higher exposure concentration. In total, 18% of the inhaled mass of waterpipe SH smoke deposited in the respiratory tract and 15% of the cigarette smoke. Thus, at similar exposure concentrations the inhaled dose would be about 20% higher for waterpipe SH smoke particles. For both types of SH smoke particles that deposited in the lungs, 47-49% of the mass deposited in the pulmonary region of the lungs, 28% in the tracheobronchial region and 23-26% in the head airways.

Fig. 7. Total respiratory tract deposition of the SH smoke particles by mass in the range 10-600 nm during one hour exposure at relaxed conditions. Values are calculated as averages for men and women during nasal breathing while sitting.

Discussion

In comparison with the amounts of ergosterol and LPS previously found in cigarette tobacco (Larsson et al., 2012) we expected lower amounts in waterpipe tobacco of which only approximately 1/3 actually is tobacco (with the balance comprising glycerol, water, and other additives). Taken this into consideration the amounts in the waterpipe tobacco samples are in general agreement with those from previous investigations of tobacco of cigarettes manufactured in China, Vietnam, and Korea. For example, the concentrations of ergosterol/mg tobacco was 0.228-0.810 ng as compared with local brands tobacco in China and Vietnam (0.3-2.4 ng) (Larsson et al., 2008). Also concentrations of LPS (1.2-2.2 pmol/mg) are similar to the amounts of tobacco purchased in Korea (5.7-10.0 pmol/mg) (Larsson et al., 2008) as well as international brands e.g. Camel Turkish Royal (6.88 pmol/mg) (Larsson et al., 2012).

Waterpipe MS smoke contained 31-180 ng of ergosterol per smoking session, which is 4-12 times lower than the amounts found in MS of one cigarette of an international brand. However, the amounts of LPS in waterpipe MS smoke (1425-2393 pmol) were similar to those previously found in the smoke of one cigarette (Larsson et al., 2012); notably, the amount of tobacco in one cigarette is only one-tenth of the amount used in one waterpipe smoking session. These results may be partly explained by the fact that there is much more of ergosterol in the tobacco of cigarettes of international brands than in the studied samples of waterpipe tobacco (see above).

Waterpipe MS smoke contained approximately 1.99% (84.4 ng) of the total amount of ergosterol present in the tobacco used for smoking and 9.47% (1800 pmol) of the total amount of LPS. These data may indicate that LPS survives the smoking process to a larger extent than ergosterol, analogously with previous findings by Larsson et al. (2012) reporting 3.65-8.23% of ergosterol and 10.02-20.13% of LPS in MS cigarette smoke in relation to the amounts in the tobacco. In the same study (Larsson et al., 2012) was found that SS smoke of one cigarette held 17-78 ng (0.30-0.82%) of ergosterol and 41-71 pmol (0.42-1.10%) of LPS while we found that SS smoke from one waterpipe smoking session contained 0-2.37 ng (0.02%) of ergosterol and 10.8-24.7 (0.09%) of LPS. Thus SS cigarette smoke contains higher amounts of microbial components than SS waterpipe smoke. Exposure to tobacco-derived microbial components during smoking may depend upon the temperature and humidity of the tobacco as well as the individual smoking habit. It is known that peak tobacco temperatures attained in the waterpipe are several hundred degrees lower than those obtained in the cigarette (Shihadeh, 2003).

Approximately 8.45% of the total amount of LPS present in the tobacco used in the waterpipe smoke experiment was found, of which 3.81% (724.4 pmol/session) was found in MS smoke and 4.64% in the water. In the previous experiment (Table 1) we found twice as much of LPS/session (1800 pmol); the difference may be explained by differences between the tobacco used. The LPS found in the water may stem from the smoke, from unburned tobacco, or both. The reason for the decrease of the endotoxin concentration in the water (as measured by the Limulus test) from 30 EU/ml before the smoking to 6 EU/ml after the smoking may be explained by adsorption of the LPS on the smoke particles. These findings are in agreement with previous results at our laboratory where tobacco smoke ash was found to adsorb endotoxin in a water solution making it undetectable by the Limulus test (unpublished results). With similar amounts of tobacco being smoked, cigarette SH smoke was found to be twice as rich in total PAHs as waterpipe SH smoke. These findings are in agreement with Daher et al. (2010) where it was suggested that smoking waterpipe may emit approximately the same amounts of PAHs as smoking two cigarettes. While the average sum of PAHs found in waterpipe SH smoke was less than half of the amounts found in cigarette SH smoke, considering the more carcinogenic 5- and 6-ring compounds, waterpipe SH resulted in similar or greater ambient concentrations than produced by smoking 5 cigarettes. The CO concentration in waterpipe MS smoke was calculated as 254 mg/session, similar to the findings of Shihadeh and Saleh (2005). It is known that most of the CO in waterpipe smoke is produced by the burning coal. In our aerosol chamber studies on SH smoke we found that smoking waterpipe increased up to 60 ppm the concentration of CO, similar to the findings of Fromme et al. (2009). By contrast, when smoking 5 cigarettes the concentration of CO did not exceeded 3 ppm.

Cigarette SH smoke (calculated for the five cigarettes used per smoking session) gave air concentrations of approximately 87.5 ng/m3 of ergosterol and 22.2 pmol/m3 of LPS; viz. 5 – 13 times larger amounts than those found by Szponar et al. (2012) in the homes of smokers. Waterpipe SH smoke gave a similar amount of LPS as smoking one cigarette (2.8 pmol/m3) whereas ergosterol was not detected. To the best of our knowledge, here for the first time it is shown that waterpipe smoke contains microbiological compounds and that individuals present in a location with ongoing waterpipe smoking are exposed to a bioaerosol containing both bacterial and fungal components in addition e.g. to several carcinogenic PAHs. In forthcoming studies it would be interesting to study air concentrations of these components in a real scenario e.g. waterpipe smoke in cafes.

The results of the waterpipe smoke particle size distribution are broadly consistent with those obtained in an earlier studies by Monn et al. (2007) and Daher et al. (2010) in which waterpipe and cigarette smoke particle size distributions were compared. The higher mass concentration of the cigarette smoke is due to the larger size of the particles since both types of smoke particles had approximately similar density (Figure 6). The somewhat higher mass concentration from the TEOM may be explained by the large cigarette smoke particles that were not covered in the size distribution measurement. The measured effective densities fits well with the determined effective density of particles from low-temperature combustion of biomass material (wood pellets) reported in a previous study (Löndahl et al., 2008). The measured effective densities are higher than for typical combustion soot particles (e.g. see Rissler et al. (2013)). This is likely explained both by a different chemistry of the particles and by the high humidity that the SH smoke is exposed to in the respiratory tract and the waterpipe. Agglomerated particles with hygroscopic material are likely to collapse into a more compact form at high humidity.

The health effects are caused by the smoke that enters the body, primarily through inhalation. Thus, the estimated deposited dose of SH smoke in the respiratory tract provide important complementary information to exposure concentrations and particle chemistry. The calculations of the deposited dose were based on the MPPD model, which is both well-established and freely available. Adjustment of the deposition fractions were made for hygroscopicity of the particles. Also the effective density of the SH smoke particles were taken into account.

The fraction of inhaled SH smoke particles that was calculated to be deposited in the respiratory tract was 18% and 15% for the waterpipe and cigarettes, respectively. This is low compared to many other types of air pollution (Löndahl et al., 2013). The somewhat larger fraction of deposited waterpipe smoke particles is explained by the higher fraction of small (< 200 nm) particles (Figure 3). These particles have an increased deposition because of their higher diffusivity. For both types of smoke almost half the deposited mass would be found in the pulmonary region, which provides a close path for chemical compounds to the systemic circulation. Hence the microbial compounds may very well reach sensitive parts of the body, if assuming that they are homogenously distributed in the SH smoke particles.

The present study shows that waterpipe tobacco and smoke contain compounds of fungal and bacterial origin including LPS. Thus waterpipe smoking indoors will worsen the indoor air quality. These results are important since it is known that exposure to bioaerosols is related to the development of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and other respiratory disorders. The new data may be useful in antismoking campaigns.

Highlights.

Waterpipe tobacco and smoke contain LPS and fungal biomass.

A strong correlation was found between TPM and LPS in MS waterpipe smoke.

Exposure to SH waterpipe smoke leads to deposition of particles in the airways.

Acknowledgments

Grants from Flight Attendant Medical Research Institute (FAMRI project CIA 092049), The Swedish Research Council for Environment, Agricultural Sciences and Spatial Planning (FORMAS project 242-2008-343), The Swedish Research Council (project 621-2011-3560), VINNOVA - Swedish Governmental Agency for Innovation Systems through (project 2010-01004), and the US NIH (R01 DA025659) are gratefully acknowledged. We would like to thank Francisco Márquez Fernández for assistance in SH smoke experiments and Bo Strandberg for analysis of PAHs.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Akl EA, Gunukula SK, Aleem S, Obeid R, Abou Jaoude P, Honeine R, et al. The prevalence of waterpipe tobacco smoking among the general and specific populations: a systematic review. Bmc Public Health. 2011;11 doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blank MD, Cobb CO, Kilgalen B, Austin J, Weaver MF, Shihadeh A, et al. Acute effects of waterpipe tobacco smoking: A double-blind, placebo-control study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;116:102–109. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb CO, Sahmarani K, Eissenberg T, Shihadeh A. Acute toxicant exposure and cardiac autonomic dysfunction from smoking a single narghile waterpipe with tobacco and with a “healthy” tobacco-free alternative. Toxicol Lett. 2012;215:70–5. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2012.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins DR, Flagan RC, Seinfeld JH. Improved inversion of scanning DMA data. Aerosol Science and Technology. 2002;36:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Daher N, Saleh R, Jaroudi E, Sheheitli H, Badr T, Sepetdjian E, et al. Comparison of carcinogen, carbon monoxide, and ultrafine particle emissions from narghile waterpipe and cigarette smoking: Sidestream smoke measurements and assessment of second-hand smoke emission factors. Atmos Environ (1994) 2010;44:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromme H, Dietrich S, Heitmann D, Dressel H, Diemer J, Schulz T, et al. Indoor air contamination during a waterpipe (narghile) smoking session. Food Chem Toxicol. 2009;47:1636–41. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2009.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasday JD, Bascom R, Costa JJ, Fitzgerald T, Dubin W. Bacterial endotoxin is an active component of cigarette smoke. Chest. 1999;115:829–35. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.3.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katurji M, Daher N, Sheheitli H, Saleh R, Shihadeh A. Direct measurement of toxicants inhaled by water pipe users in the natural environment using a real-time in situ sampling technique. Inhal Toxicol. 2010;22:1101–9. doi: 10.3109/08958378.2010.524265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliucininkas L, Martuzevicius D, Krugly E, Prasauskas T, Kauneliene V, Molnar P, et al. Indoor and outdoor concentrations of fine particles, particle-bound PAHs and volatile organic compounds in Kaunas, Lithuania. J Environ Monit. 2011;13:182–91. doi: 10.1039/c0em00260g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson L, Pehrson C, Dechen T, Crane-Godreau M. Microbiological components in mainstream and sidestream cigarette smoke. Tob Induc Dis. 2012;10:13. doi: 10.1186/1617-9625-10-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson L, Szponar B, Pehrson C. Tobacco smoking increases dramatically air concentrations of endotoxin. Indoor Air. 2004;14:421–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2004.00290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson L, Szponar B, Ridha B, Pehrson C, Dutkiewicz J, Krysińska-Traczyk E, et al. Identification of bacterial and fungal components in tobacco and tobacco smoke. Tob Induc Dis. 2008;4:4. doi: 10.1186/1617-9625-4-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löndahl J, Möller W, Pagels JH, Kreyling WG, Swietlicki E, Schmid O. Measurement Techniques for Respiratory Tract Deposition of Airborne Nanoparticles: A Critical Review. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2013 doi: 10.1089/jamp.2013.1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löndahl J, Pagels J, Boman C, Swietlicki E, Massling A, Rissler J, et al. Deposition of biomass combustion aerosol particles in the human respiratory tract. Inhal Toxicol. 2008;20:923–33. doi: 10.1080/08958370802087124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMurry PH, Wang X, Park K, Ehara K. The relationship between mass and mobility for atmospheric particles: A new technique for measuring particle density. Aerosol Science and Technology. 2002;36:227–238. [Google Scholar]

- Monn C, Kindler P, Meile A, Brandli O. Ultrafine particle emissions from waterpipes. Tob Control. 2007;16:390–3. doi: 10.1136/tc.2007.021097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagels J, Wierbicka A, Nilsson E, Isaxon C, Dahl A, Gudmundsson A, et al. Chemical composition and mass emission factors of candle smoke particles. Journal of Aerosol Science. 2009;40:193–208. [Google Scholar]

- Rissler J, Messing ME, Malik AI, Nilsson PT, Nordin EZ, Bohgard M, et al. Effective Density Characterization of Soot Agglomerates from Various Sources and Comparison to Aggregation Theory. Aerosol Science and Technology. 2013;47:792–805. [Google Scholar]

- Rissler J, Nordin EZ, Eriksson AC, Nilsson PT, Frosch M, Sporre MK, et al. Effective Density and Mixing State of Aerosol Particles in a Near-Traffic Urban Environment. Environ Sci Technol. 2014 doi: 10.1021/es5000353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sajid KM, Akhter M, Malik GQ. Carbon monoxide fractions in cigarette and hookah (hubble bubble) smoke. J Pak Med Assoc. 1993;43:179–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleh R, Shihadeh A. Elevated toxicant yields with narghile waterpipes smoked using a plastic hose. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2008;46:1461–1466. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saraf A, Larsson L. Use of gas chromatography ion-trap tandem mass spectrometry for the determination of chemical markers of microorganisms in organic dust. J Mass Spectrom. 1996;31:389–396. [Google Scholar]

- Sebastian A, Pehrson C, Larsson L. Elevated concentrations of endotoxin in indoor air due to cigarette smoking. J Environ Monit. 2006;8:519–22. doi: 10.1039/b600706f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepetdjian E, Abdul Halim R, Salman R, Jaroudi E, Shihadeh A, Saliba NA. Phenolic compounds in particles of mainstream waterpipe smoke. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15:1107–12. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepetdjian E, Shihadeh A, Saliba NA. Measurement of 16 polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in narghile waterpipe tobacco smoke. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2008;46:1582–1590. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2007.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shihadeh A. Investigation of mainstream smoke aerosol of the argileh water pipe. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2003;41:143–152. doi: 10.1016/s0278-6915(02)00220-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shihadeh A, Saleh R. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, carbon monoxide, “tar”, and nicotine in the mainstream smoke aerosol of the narghile water pipe. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2005;43:655–61. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2004.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shihadeh A, Salman R, Jaroudi E, Saliba N, Sepetdjian E, Blank MD, et al. Does switching to a tobacco-free waterpipe product reduce toxicant intake? A crossover study comparing CO, NO, PAH, volatile aldehydes, “tar” and nicotine yields. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2012;50:1494–1498. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.02.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szponar B, Pehrson C, Larsson L. Bacterial and fungal markers in tobacco smoke. Science of the Total Environment. 2012;438:447–451. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.08.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]