Abstract

Cognate T/B cell interactions and CD40/CD154 costimulation are essential for productive humoral immunity against T-dependent antigens. We reported that memory CD4 T cells can deliver help to B cells and induce pathogenic IgG alloantibodies (alloAb) in the absence of CD40/CD154 interactions. To determine cytokine requirements for CD40-independent help, CD40−/− mice containing differentiated subsets of donor-reactive memory helper T cells were used as heart allograft recipients. Th1 and Th17, but not Th2, memory CD4 T cells elicited high titers of anti-donor Ab. Ab induced by Th17 memory CD4 T cells had decreased reactivity against donor MHC class I molecules and inferior ability to cause complement deposition in heart allografts compared to Ab induced by Th1 cells suggesting a requirement for IFNγ during CD40-independent help. IFNγ neutralization inhibited helper functions of memory CD4 T cells in both CD40−/− recipients and in wild type recipients treated with anti-CD154 mAb. Our results suggest that IFNγ secreted by pre-existing memory helper cells determines both isotype and specificity of donor-reactive alloAb and can thus affect allograft pathology. This information may be valuable for identifying transplant patients at risk for de novo development of pathogenic alloAb and for preventing alloAb production in T cell sensitized recipients.

Introduction

Productive humoral immune responses against thymus-dependent antigens require cognate interactions between B cells and T helper cells (1, 2). Along with specific TCR/peptide/MHC class II interactions, the engagement of CD40 on B cells and CD154 expressed by activated CD4 T cells is critical for cognate T cell help (3). Genetic defects in CD40 or its ligand or therapeutic interference with CD40/CD154 pathway result in impairment in germinal center formation, isotype switching and high-affinity antibody (Ab) production in response to thymus-dependent antigens in mice and humans (4–9).

Analogous to immune responses against infections and model antigens, the generation of high affinity donor-reactive alloantibodies (alloAb) after transplantation is dependent on T cell help and CD40/CD154 costimulation (10–12). Blocking the CD40/CD154 pathway inhibited donor-specific T cell responses, prevented generation of anti-donor alloAb and facilitated prolonged graft survival and often tolerance in multiple rodent transplant models (13–17). However, the same therapies were much less efficacious when applied to non-human primates (18–20). Compared to inbred rodents housed in pathogen-free facilities, large animals and humans contain many more alloreactive memory T cells arising from previous exposure to alloantigens and infectious agents with cross-reactivity to alloantigens (defined as heterologous immunity) or from homeostatic expansion following lymphopenia (21, 22). During the past decade, several groups including ours established that donor-reactive memory T cells present in transplant recipients can confer resistance to the effects of conventional costimulatory blockade (23–27).

B cell activation and class switch recombination are regulated by cytokines secreted by differentiated CD4 T cell subsets. While the roles of IL-4 and IFNγ in Ab responses are well established (28–30), IL-17 has also been reported to promote germinal center development and humoral responses in autoimmune-prone mice (31). Using a mouse model of heart transplantation, we recently reported that donor-reactive memory CD4 T cells can deliver help to B cells and induce high titers of IgG alloAb in the absence of CD40/CD154 interactions and that the induced alloAb contribute to heart allograft injury (32). Notably, donor-specific memory CD4 T cells induced via in vitro or in vivo priming in our studies were heterogeneous in their phenotype and cytokine profile. Thus, the identity of memory helper cells capable of inducing alloAb in CD40-independent manner as well as the molecular requirements for such help remained unclear. These issues have direct relevance to clinical transplantation as several reagents targeting CD40/CD154 costimulatory pathway are being developed and tested in pre-clinical transplantation models (33–35).

The T cell repertoire of many humans contains memory CD4 T cells polarized to the Th1, Th2 and Th17 functional phenotypes that are likely to be alloreactive (36, 37). The abilities of differentiated CD4 helper T cell subsets to initiate alloAb production and thus inflict allograft pathology in the presence or absence of CD40-CD154 costimulation have not been previously investigated. Here we demonstrate that similar to unpolarized memory CD4 T cells, memory Th1 and Th17 cells induce high titers of anti-donor IgG in response to heart allografts placed in CD40−/− recipients. AlloAb induced by Th17 cells, however, had marked decreases in reactivity to donor MHC class I molecules and inferior potency to induce C4d deposition in the heart allograft vasculature compared to alloAb induced by Th1 cells. Unexpectedly, Th2 cells with the same specificity failed to provide CD40-independent help for IgG alloAb generation. Furthermore, recipient treatment with anti-IFNγ mAb inhibited IgG alloAb responses initiated by memory CD4 T cells in both CD40−/− and wild type recipients treated with anti-CD154 mAb. These studies indicate that the ability of memory CD4 T helper T cells to produce IFNg determines both the isotype and the specificity of donor reactive alloAb and can thus affect allograft pathology. The results should be valuable in identifying transplant patients at risk for de novo development of pathogenic alloAb and for preventing alloAb production in T cell sensitized recipients.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Female C57Bl/6J (B6, H-2b), B6.129P2-Tnfrsf5tm1Kik/J (CD40−/−, H-2b), B6.129S7-Rag1tm1Mom/J (RAG1−/−, H-2b) and male BALB/cJ (BALB/c, H-2d), SJL/J (SJL, H-2s) and C3H/HeJ MMTV- (C3H, H-2k) mice, aged 6–8 weeks, were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Male and female C57Bl/10NA;-(Tg)TCR Marilyn-(KO) Rag2 N11, N2 mice (Mar, H-2b) were obtained from Dr. Polly Matzinger (NIH) and crossed onto the CD45.1 expressing background. C57Bl/6 mice expressing Kd transgene (38) were kindly provided by Dr. R. Pat Bucy (University of Alabama, Birmingham AL). All animals were maintained and bred in the pathogen-free facility at Cleveland Clinic. All procedures involving animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Cleveland Clinic.

Generation of alloreactive memory CD4 T cells

Memory Mar CD4 T cells were generated as previously published (39). Briefly, spleen cells from young (4–6 weeks) Mar female mice were stimulated in vitro with 3 µM HYDby peptide (NAGFNSNRANSSRSS, Research Genetics, Huntsville, AL). After 4 days, cells were washed, counted and intravenously injected into naïve B6 or CD40−/− female mice (5×106 cells/mouse or fewer in selected experiments). In each experiment, recipients received cells derived from a common pool of activated Mar T cells. Animals were rested for 3 weeks prior to use as heart allograft recipients. To generate polarized subsets of Mar cells, naïve CD45.1 Mar spleen cells were cultured for 4 days with 3µM HYDbyp and one of the following: 1) 10 ng/ml rIL-12 (PeproTech Inc., Rocky Hill, NJ) and 10µg/ml anti-IL-4 mAb (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) for Th1 polarization; 2) 200 ng/ml rIL-4 (PeproTech Inc.), 10 µg/ml anti-IL-12 and 10 µg/ml anti-IFNγ mAb (both from BD Pharmingen) for Th2 polarization; and 3) 5 ng/ml rTGFβ (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), 10 ng/ml rIL-6 (PeproTech Inc.), 10 µg/ml anti-IFNγ and 10 µg/ml anti-IL-4 mAb for Th17 polarization. An aliquot of polarized harvested cells was washed, counted and tested for their ability to secrete IFNγ, IL-4, IL-2 and IL-17 in response to HYDby peptide in a recall ELISPOT assay as previously published (39–42). The remaining polarized CD4 T cells were injected intravenously into groups of CD40−/− female mice (5×106 cells/mouse) followed by 3 weeks of rest and the placement of an allogeneic BALB/c cardiac allograft. The frequencies of transferred CD45.1+ cells were evaluated in peripheral blood by flow cytometry at various time points after transfer, and the cytokine profile of transferred cells was assessed by a recall ELISPOT assay performed on spleen cells 21 d. after transplantation.

To generate polyclonal alloreactive memory CD4 T cells, C3H skin allografts were placed onto B6 recipients. Six weeks after rejection, recipient spleen cells were enriched for CD4+CD44hiCD62lo T cells using EasySep magnetic bead particles from STEMCELL Technologies (Vancouver, BC). More than 90% of the resulting cells were CD4+CD44hiCD62lo by flow cytometry (data not shown).

Heart transplantation and recipient treatment

Vascularized heterotopic cardiac allografts were placed and monitored as previously described (39, 42). Rejection was defined as a loss of palpable heartbeat and confirmed by laparotomy. When indicated, wild type B6 recipients were treated with anti-CD154 Ab MR1 1 day prior to the surgery (1 mg via intravenous injection; Bio X Cell, West Lebanon, NH). Anti-mouse IFNγ mAb (rat IgG2b, clone 7E.17G9; Bio X Cell) or control rat IgG (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was injected intraperitoneally on days 0, 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10 post transplant (0.5 mg/mouse/injection).

Histologic examination of recipient spleen tissues

For immunohistochemistry, tissues were fixed with acid methanol (60% methanol, 10% acetic acid). Paraffin-embedded sections (5 µm) were steamed in two changes of Trilogy-EDTA, pH 8 (Cell Marque, Hot Springs, AR) for 1 hr. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by incubation with 0.3% H2O2 in 80% Methanol and nonspecific protein interactions were blocked by incubation with a serum-free protein block (DAKO Corp, Carpinteria, CA). Slides were incubated with a 1:3,000 dilution of biotin-SP-conjugated Affinity purified F(ab’)2 fragments of goat antibodies specific for Fc-gamma of mouse IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) for 60 min at room temperature. Slides were subsequently incubated for 30 minutes with Avidin-Biotin-Enzyme Complex (ABC elite PK6100; Vector, Burlingame, CA), followed by diaminobenzidine and counterstained with Hematoxylin.

Flow cytometry

Fluorochrome-labeled antibodies for T cell phenotype analysis were purchased from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, CA) or from eBioscience (San Diego, CA). Cells were isolated from peripheral blood or spleen, bone marrow, lung and liver and stained with indicated reagents as previously described (39, 42, 43). At least 200,000 events/sample were acquired on a BD Bioscience FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) followed by data analysis using FlowJo software (Tree Star Inc., Ashland, OR). To isolate spleen cell populations, splenocytes were stained with fluorochrome-labeled antibodies (BD Pharmingen and eBioscience), and populations of live CD4+ (helper T cells), B220+ (mostly B cells with some plasmacytoid dendritic cells), CD11c+ cells (mostly dendritic cells), Gr1+ cells (predominantly neutrophils), and F4/80+ cells (monocytes/macrophages) were separated using high speed flow sorter (FACSAria, BD Biosciences). The purity of all isolated subsets was > 97%.

Cytokine ELISPOT assay

Assays were performed as previously described using capture and detecting anti-mouse IFNγ, anti-mouse IL-2, anti-mouse IL-4 and anti-mouse IL-17 mAb from BD Pharmingen (44, 45). Recipient spleen cells were stimulated with mitomycin C-treated donor BALB/c, third party SJL or self B6 spleen cells or with HYDby peptide for 24 h. Responder cells were titrated from 400,000 to 20,000 per well with the addition of 400,000 stimulator cells per well. The resulting spots were analyzed using an ImmunoSpot Series 4 analyzer (Cellular Technology, Cleveland, OH).

Measurement of serum alloAb titers

Donor BALB/c, third party SJL and congenic B6.Kd thymocytes were isolated and 1x106 cell aliquots were incubated with 100µl of serially diluted recipient serum or with non-diluted cell culture supernatant. Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG, phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-mouse IgG1, FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgG2a, FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgG3 and biotinylated anti-mouse IgG2b followed by PE-Streptavidin conjugate were used as detecting antibodies at a 1:50 – 1:100 dilution (all from BD Pharmingen). Rat anti-mouse IgG2a monoclonal Ab R19-15 used in our studies was raised against pooled BALB/c and C57BL/6 Ig and thus has reactivity to both IgG2a and IgG2c. The staining was performed as previously published by our group (46, 47). Cells were washed, fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde, and analyzed by flow cytometry. For every sample and every IgG isotype, the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of each dilution was determined. The dilution that returned the MCF to the level observed when thymocytes were stained with an 1:90 dilution of naïve B6 serum was divided by two and reported as the titer. Binding to B6.Kd target cells was presented as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) at different serum dilutions.

IgG ELISPOT Assay

The frequencies of IgG and IgM secreting antibody secreting cells (ASC) were determined using ELISpot PLUS for mouse IgG and IgM kits (MABTECH AB, Nacka Strand, Sweden) as previously published (32, 46). Briefly, recipient cells isolated from spleen, graft-draining mediastinal lymph nodes and BM were cultured for 20 h in RPMI media supplemented with 5% of Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) in 96-well plates coated with anti-mouse IgG Ab. Then, either biotinylated-anti-IgG, biotinylated-anti-IgM or biotinylated Dd or Db molecules (5µg/ml, provided by the NIH Tetramer Core Facility at Emory University, Atlanta, GA) was added as detection reagent for two hours at room temperature. After extensive washes, the plates were incubated with Streptavidin-Alkaline Phosphatase for one hour at room temperature followed by BCIP/NBT substrate. The numbers of spots per well and the cumulative spot size distribution were analyzed using an ImmunoSpot Series 2 Analyzer (Cellular Technology Ltd., Shaker Heights, OH).

RNA isolation and quantitative real-time PCR analysis

Harvested spleens were immediately frozen by immersion into liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was isolated from individual samples using TriZol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Reverse transcription was performed using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit, quantitative real-time PCR was done on a 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System instrument using Taqman Fast Universal PCR Master Mix (2X), No AmpEraseUNG (all from Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Probes and primers were from Taqman gene expression assay reagents (Applied Biosystems): BAFF (Mm00446347_m1), APRIL (Mm03809849_s1), BAFFR (Mm00840578-g1), and TACI (Mm00840182_m1). Data were normalized to Mrpl 32 RNA amplification level in each sample and calculated relative to the expression of the target gene in total spleen cells isolated from CD40−/− recipients of BALB/c heart allografts or in CD45- spleen cells isolated from wild type B6 recipients of BALB/c heart allografts.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses to determine differences between groups for flow cytometry assays and recall immune responses were performed using a non-parametric equivalent of one-way ANOVA, the Kruskal-Wallis test. When the overall p value was <0.05, pairwise comparisons were carried out using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney test. A value of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Heart allograft survival was compared between groups by Kaplan-Meier analysis.

Results

Differentiation pathway of memory CD4 T cells determines their ability to provide CD40-independent help

We recently reported that donor-reactive memory CD4 T cells can provide help for the induction of donor-reactive IgG alloAb in the absence of CD40/CD154 interactions (32). To extend these studies by comparing helper functions of naïve and memory CD4 T cells with the same specificity, we used TCR transgenic mice (Mar) on B6.RAG2−/− background. Mar T cells are specific for the HYDby peptide presented by I-Ab. After placement of male allogeneic heart transplants into C57BL/6 (B6, H-2b) female recipients, transferred Mar T cells recognize donor male antigen presented by female antigen presenting cells through the indirect pathway (Figure S1). Similarly to polyclonal memory CD4 T cells, Mar memory T cells provide help for the production of Ab against donor MHC molecules (39, 42).

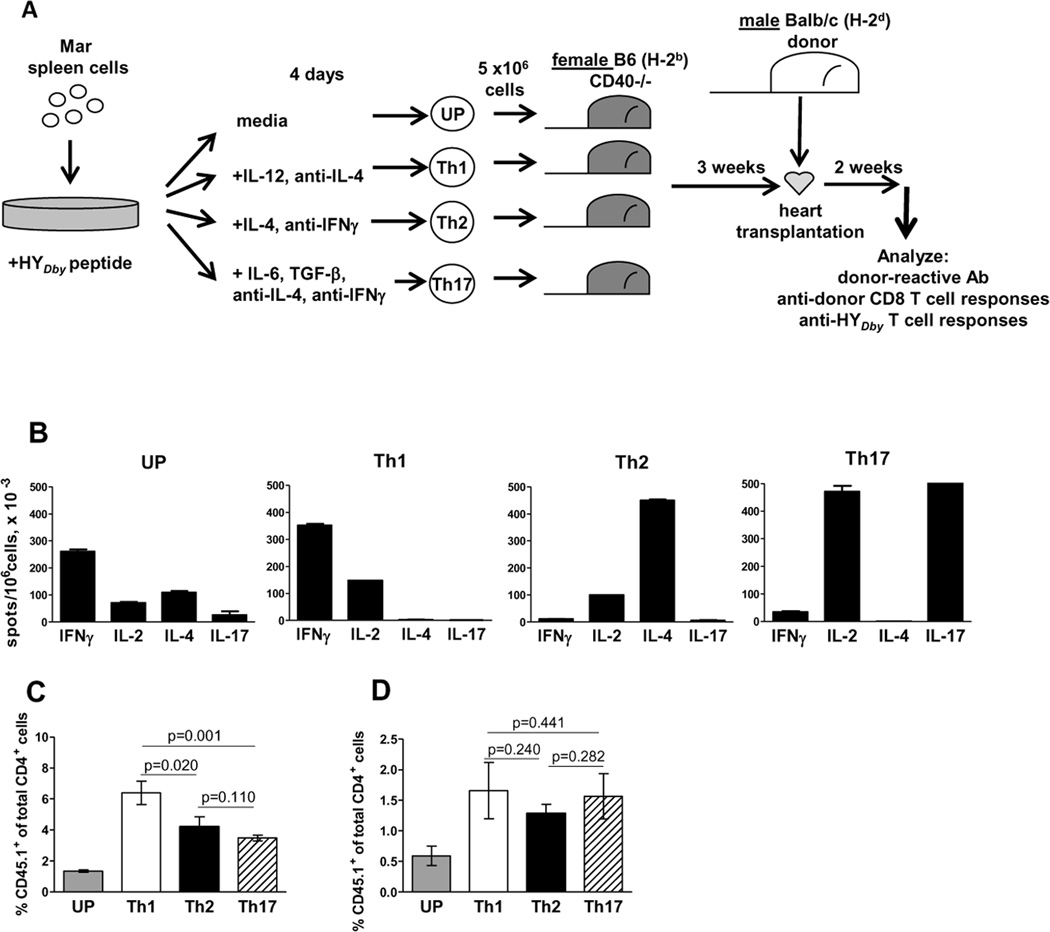

In our previous studies, in vitro primed memory Mar T cells were heterogeneous in their cytokine profile: 26±8% cells secreted IFNγ; 11±4% - IL-4; 7±4% - IL-2; and, 2.5±1.4% - IL-17. To begin to address the cytokine requirements for CD40-independent help by memory CD4 T cells, we tested the ability of differentiated memory CD4 helper subsets to induce alloAb in a CD40-independent fashion. Naïve Mar cells were activated in vitro with HYDby peptide and polarized toward Th1, Th2, and Th17 phenotypes by the addition of cytokines plus cytokine neutralizing Ab (Figure 1A). The extent of polarization was assessed by ELISPOT assay (Figure 1B) and the resulting cells were injected into CD40−/− B6 (H-2b) female mice. After 21 d. of in vivo rest, the numbers of the transferred Th2 and Th17 cell subsets were comparable, whereas Th1 polarized cells demonstrated even better survival (Figure 1C). All mice then received BALB/c (H-2d) male heart allografts. Two weeks after transplantation, transferred Mar CD4 T cells were detectable in recipients’ spleens at comparable frequencies (Figure 1D) and maintained their pre-transfer cytokine profiles as determined by a recall ELISPOT assay (not shown).

Figure 1.

Cytokine profiles and in vivo survival of TCR transgenic CD4 T cell subsets. A. Experimental design. Naïve CD45.1+ Mar T cells stimulated with HYDby peptide were left unpolarized (UP) or polarized towards Th1, Th2 and Th17 phenotypes with cytokines and cytokine neutralizing Ab. B. After 4 d. culture, cells were re-stimulated with HyDby peptide in recall ELISPOT assays for IFNγ, Il-2, IL-4 or IL-17. C, D. The differentiated subsets of in vitro activated Mar cells were injected into B6.CD40−/− female mice followed by a male BALB/c heart transplantation three weeks later. The percentages of CD4+CD45.1+ cells were evaluated by flow cytometry in the peripheral blood three weeks after adoptive transfer (C) and in the spleen two weeks after heart allograft placement (D). N = 5–7 mice/group.

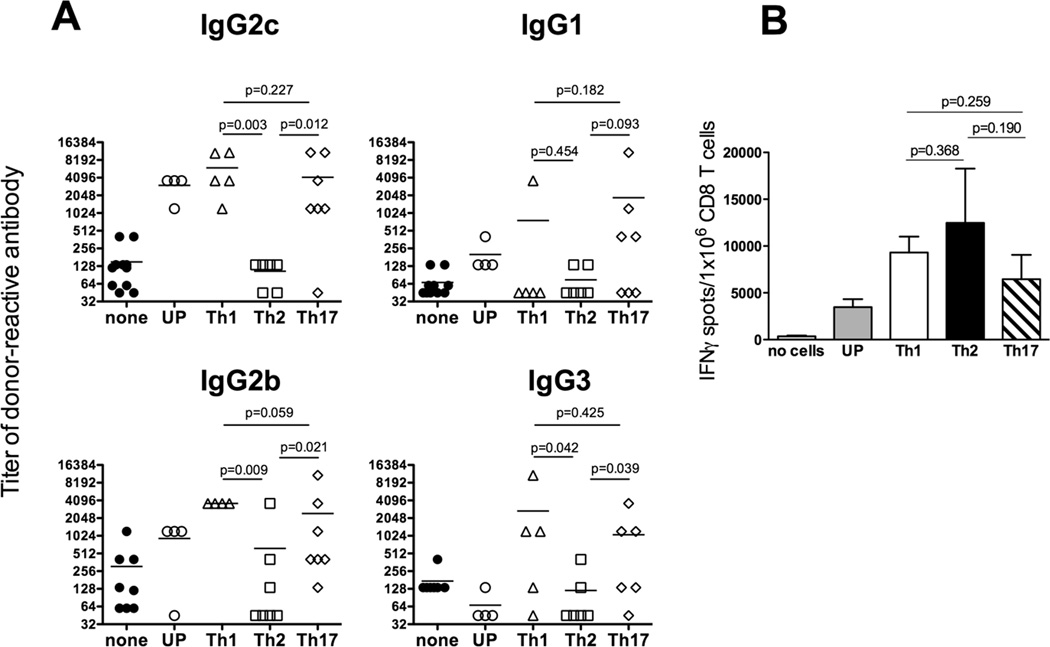

Anti-donor Ab elicited by Th1 and Th17 memory Mar cells in CD40−/− allograft recipients were dominated by the IgG2c, IgG2b and IgG3 isotypes (Figure 2A). Th1 and Th17 memory Mar cells differed in their ability to initiate a switch to the IgG1 isotype as intermediate or high IgG1 titers were detected in 4 out of 7 recipients injected with Th17 cells and only in 1 out of 5 recipients containing Th1 memory cells. In contrast, Th2 memory Mar cells failed to initiate efficient IgG alloAb responses in CD40−/− recipients (Figure 2). Despite the absence of help for alloAb production, Th2 memory T cells efficiently induced endogenous CD8 T cell alloresponses in the absence of CD40 (Figure 2B). We also performed parallel adoptive transfer of the memory T cell subsets into CD40-sufficient CD4−/− mice. In this setting, Th2 polarized Mar memory T cells induced high titers of anti-donor IgG1 and IgG2b Ab with intermediate titers of IgG2c (Figure 3). Thus, the functions of memory Th2 cells delivering help for B cell versus CD8 T cell responses are differentially affected by the lack of CD40/CD154 costimulation.

Figure 2.

Helper functions of Th1, Th2, and Th17 memory cells are differentially affected by the absence of CD40. A. Donor-reactive Th2 memory T cells fail to induce IgG alloAb in the absence of CD40 signaling. Mar cells were activated in vitro with HYDby peptide and polarized towards Th1, Th2 and Th17 phenotypes or left unpolarized (UP). The resulting Mar T cell subsets were injected into CD40−/− female mice followed by BALB/c male heart transplantation three weeks later. Serum titers of donor- or third party-reactive IgG alloAb were determined on d. 14 post transplant. The titers of third party C3H-reactive Ab were ≤ 135 for all IgG isotypes. B. Th1, Th2 and Th17 memory cells provide efficient help for donor-reactive CD8 T cell activation in the absence of CD40. CD40−/− heart allograft recipients containing differentiated subsets of memory Mar cells were sacrificed at 14 days after transplantation. Spleen CD8 T cells were isolated and tested in a recall IFNγ ELISPOT assay against donor BALB/c or third party C3H stimulator cells. The frequency of cells secreting IFNγ in response to third party stimulator cells was < 200 per 1x 106 CD8 T cells in all groups. N = 4–5 mice/group. Experiment was performed three times with similar results.

Figure 3.

Th2 memory T cells induce high titers of donor-reactive alloAb in CD40-sufficient heart allograft recipients. Mar cells were activated in vitro with HYDby peptide and polarized towards Th1, Th2 and Th17 phenotypes or left unpolarized (UP). Resulting Mar T cell subsets were injected into CD4−/− female mice followed by BALB/c male heart transplantation three weeks later. Serum titers of donor- or third party-reactive IgG alloAb were determined on d. 14 post transplant. The titers of third party C3H-reactive Ab were 45 for all IgG isotypes.

Th1, but not Th17 memory helper cells induce humoral responses against donor MHC class I molecules

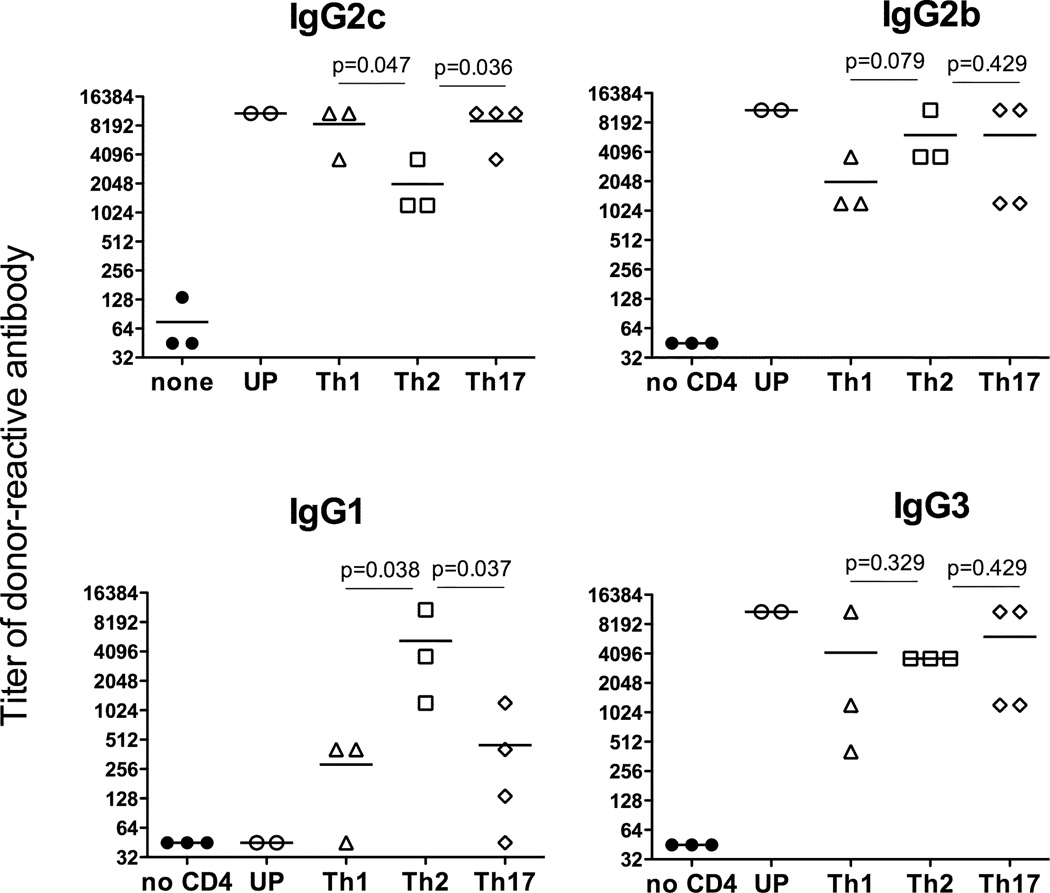

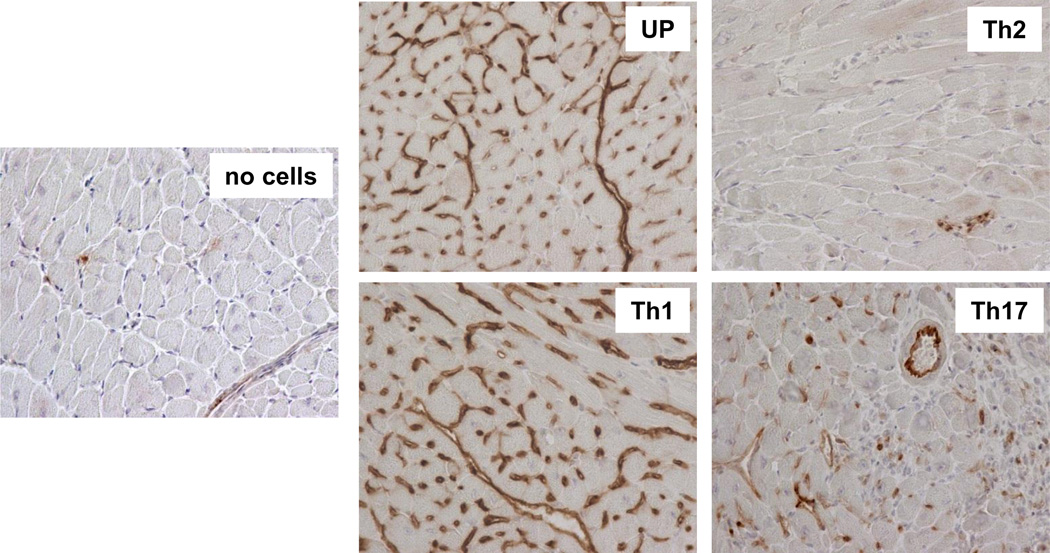

Our previous studies indicate that spleen rather than bone marrow is the primary source of donor-reactive alloAb following heart transplantation in mice (46). Immunohistochemical staining of spleen sections revealed IgG producing Ab secreting cells (ASCs) in CD40−/− recipients injected with unpolarized, Th1 and Th17 cells, but not Th2 cells (Figure 4A). Quantitative ELISPOT assay confirmed that the numbers of total IgG spots were significantly increased in recipients containing unpolarazed, Th1 and Th17 memory T cells when compared to CD40−/− recipients without memory T cell transfer or to recipients injected with Th2 Mar cells (Figure 4B). Thus, the numbers of IgG producing cells in the spleen correlated with the observed serum titers of anti-donor IgG alloAb.

Figure 4.

Th1 and Th17 cells, but not Th2 memory T cells induce IgG secreting plasma cells in CD40−/− heart transplant recipients. CD40−/− recipients containing subsets of differentiated memory Mar T cells were sacrificed two weeks after placement of male BALB/c cardiac allografts. Naïve CD40−/− mice and CD40−/− heart allograft recipients without injected memory Mar T cells were used as controls. A. Immunohistochemical staining of recipient spleen sections for IgG secreting cells. Spleen tissues were excised, fixed and embedded in paraffin. 3µm sections were prepared and stained with anti-mouse IgG Abs. The staining shown is representative of 4–5 individual grafts analyzed per group. Magnification 400x. B. The frequencies of total IgG-secreting cells in the spleen determined by ELISPOT assay. N = 5–7 mice/group.

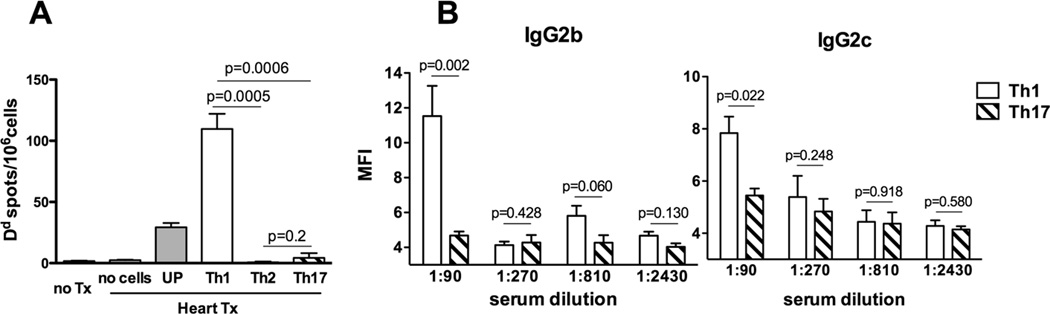

We next assessed the ability of differentiated memory helper T cell subsets to induce IgG alloAb against representative donor MHC class I molecules. We used ELISPOT assay to measure the frequencies of spleen ASCs secreting IgG reactive to donor H-2Dd as we previously published (46) and flow cytometry assay to evaluate the binding of recipient sera to congenic B6.Kd cells that express another donor MHC class I molecule, H-2Kd. Notably, in both assays Th17 memory CD4 T cells induced inferior Ab responses against donor MHC class I molecules compared to Th1 and unpolarized memory CD4 T cell subsets (Figure 5). These data indicate that the functional differentiation of memory helper T cells impacts the specificity of Ab elicited by an allograft.

Figure 5.

Th1, but not Th17 memory helper cells induce humoral responses against donor MHC class I. CD40−/− recipients containing subsets of differentiated memory Mar T cells were sacrificed two weeks after placement of male BALB/c cardiac allografts. Naïve CD40−/− mice and CD40−/− heart allograft recipients without injected memory Mar cells were used as controls. A. The frequencies of spleen cells secreting Dd-binding IgG determined by ELISPOT assay. N = 5–7 mice /group. B. Recipient sera binding to B6.Kd target cells. N = 3–4 mice/group.

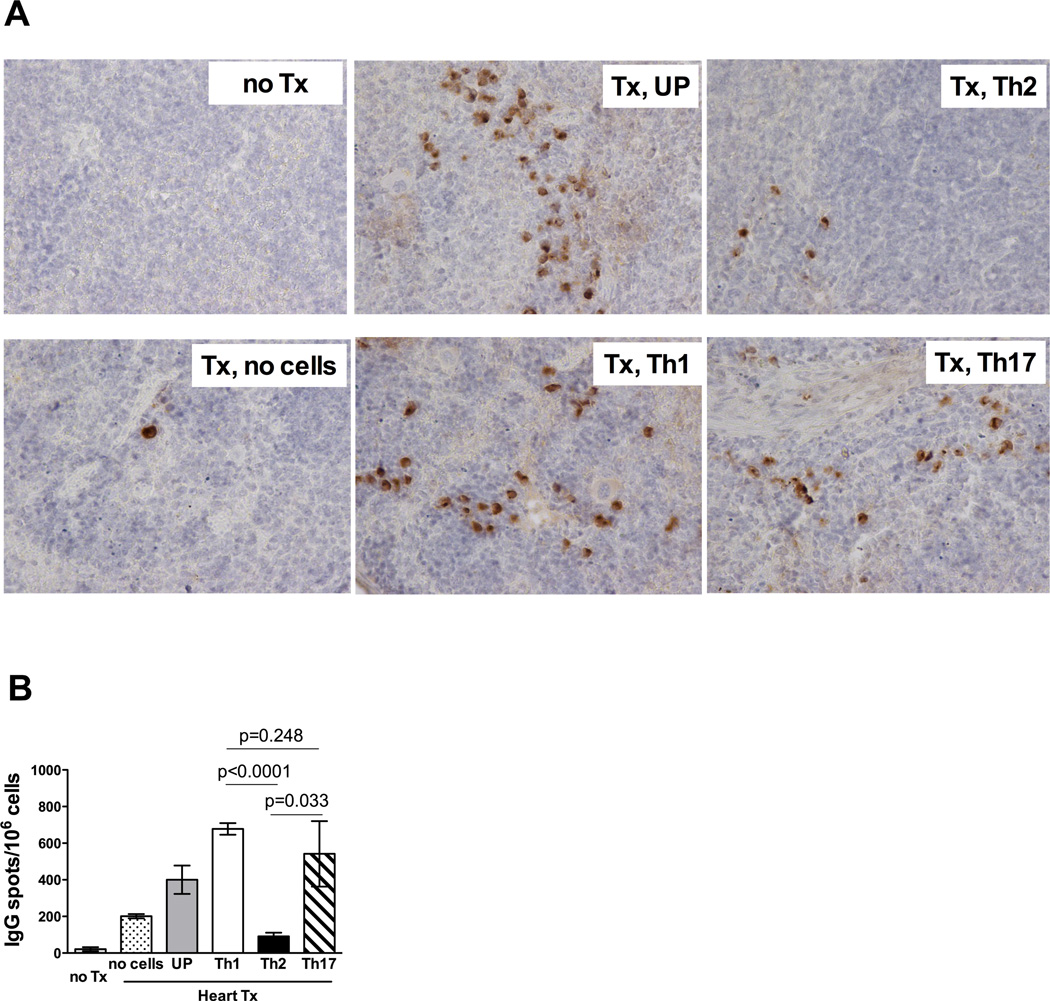

Anti-donor alloAb induced by Th1 and Th17 memory CD4 T cells differ in their ability to induce complement deposition in the graft

Despite the absence of the CD40/CD154 costimulatory pathway and the inability to generate anti-donor IgG alloAb, CD40−/− mice reject allogeneic heart transplants, even without transferred memory T cells (MST of 17.8 ± 2.3 days, (32)). Recipients injected with differentiated Mar T cell subsets demonstrated comparable survival of BALB/c heart allografts (MST of 6.9 ± 1.1 days, 7.7 ± 1.0 days, 7.0 ± 0.8 days and 8.1 ± 1.9 days for recipients containing UP, Th1, Th2 and Th17 cells, respectively) and the rejecting grafts were heavily infiltrated with CD8+ T lymphocytes (data not shown). Thus while donor-reactive alloAb induced by transferred memory Mar cells certainly contribute to graft tissue injury, the rapid rejection of heart allografts in this model is predominantly mediated by CD8 effector T cells. To test the potential pathogenicity of alloAb induced by CD4 helper cell subsets, we collected serum samples from CD40−/− heart allograft recipients containing unpolarized, Th1, Th2 or Th17 memory cells. Serum aliquots were injected into RAG1−/− recipients of BALB/c male heart allografts on days 2 and 4 after transplantation, followed by histological analysis of graft tissue on day 7 post transplant. The passive transfer of anti-donor sera induced by either unpolarized or Th1 memory Mar cells resulted in intense diffuse C4d deposition in the graft capillaries (Figure 6). The sera from CD40−/− allograft recipients containing memory Th2 cells did not induce significant complement deposition, consistent with the low titers of donor-reactive IgG alloAb. Unexpectedly, despite high titers of donor-reactive Abs induced by Th17 memory Mar cells, transfer of these sera did not lead to C4d deposition in the graft (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Anti-donor alloAb induced by Th1 and Th17 memory CD4 T cells differ in their ability to induce complement deposition in the graft. Sera from CD40−/− heart allograft recipients containing memory Mar cell subsets or from control CD40−/− recipients were collected on d. 14 and 21 post transplant. Pooled serum aliquots were intravenously injected into RAG1−/− recipients of BALB/c heart allografts on d. 2 and 4 after transplantation (200 µl per injection). Following adoptive serum transfer, heart allografts from the RAG1−/− recipients were harvested on d. 7 post transplant and immunohistochemical staining for C4d was performed on paraffin-embedded tissue sections. The images are representative of 4–5 heart allografts analyzed in each group. Magnification 200x.

Taken together, these results suggested that only memory helper T cells that secrete IFNγ (unpolarized and Th1, but not Th2 and Th17 cells) are capable of inducing pathogenic anti-donor alloAb in CD40−/− heart allograft recipients.

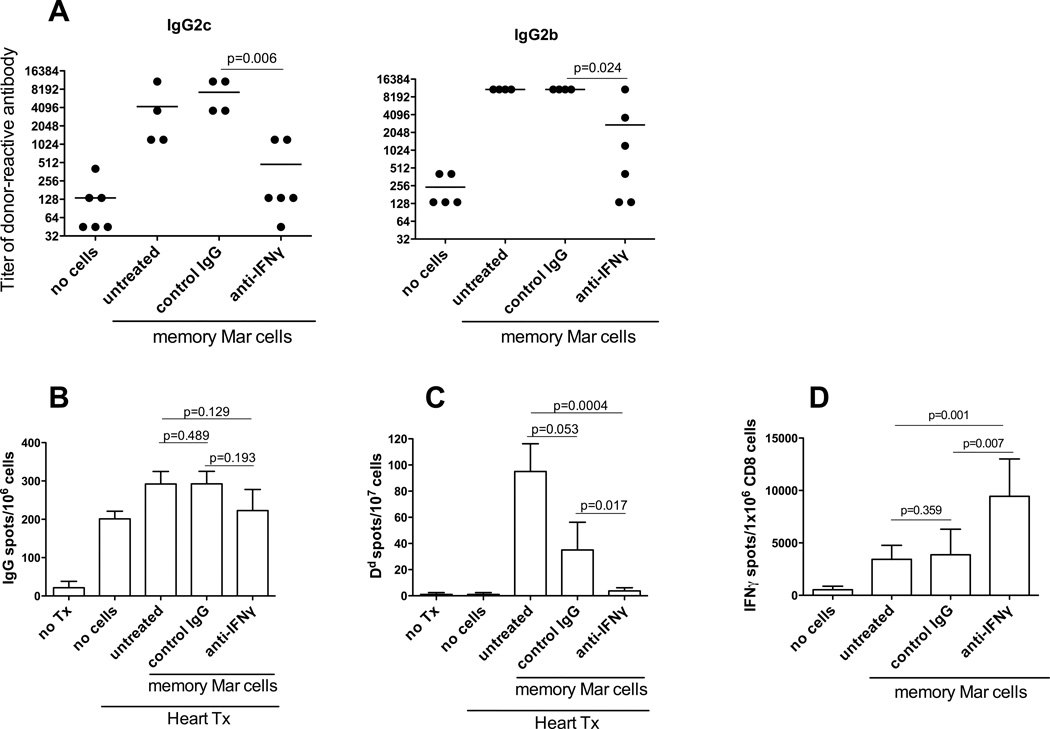

IFNγ neutralization prevents memory CD4 T cells from providing CD40-independent help to B cells

We directly tested whether IFNγ is required for CD40-independent helper functions of memory CD4 T cells. Administration of blocking anti-IFNγ Ab to CD40−/− heart allograft recipients containing unpolarized memory Mar T cells significantly decreased serum titers of IgG2b and IgG2c alloAb compared to control rat IgG treatment (Figure 7A). While recipients treated with control IgG Ab had reduced numbers of Dd-specific ASCs compared to untreated control group, possibly due to the IVIG-like effects of administered Ab, IFNγ neutralization completely prevented generation of donor MHC class I-specific Ab secreting cells (Figure 7C). In contrast, donor-reactive CD8 T cells were efficiently activated under these conditions indicating that, in the absence of CD40/CD154 interactions, memory CD4 T cells require IFNγ in order to provide help to B cells but that the help for CD8 T cells is IFNγ-independent (Figure 7D).

Figure 7.

IFNγ neutralization prevents memory CD4 T cells from providing CD40-independent help to B cells but not to donor-reactive CD8 T cells. CD40−/− female mice containing unpolarized memory Mar T cells were transplanted with BALB/c heart allografts and treated with blocking anti-IFNγ or control rat IgG Ab throughout the duration of the experiments. Recipients were sacrificed two weeks after transplantation. N = 4–6 animals/group. The experiment was performed twice with similar results. A. Serum titers of donor-reactive IgG alloAb. The titers of third party-reactive alloAb were < 135 for both IgG2c and IgG2b. B. The frequencies of total IgG-secreting spleen cells. C. The frequencies of spleen cells secreting donor Dd-binding IgG. D. IFNγ ELISPOT assays were performed on CD8 T cells isolated from recipient spleen and re-stimulated with BALB/c or third party splenocytes. The frequency of cells secreting IFNγ in response to third party stimulator cells was < 200 per 1x 106 CD8 T cells in all groups.

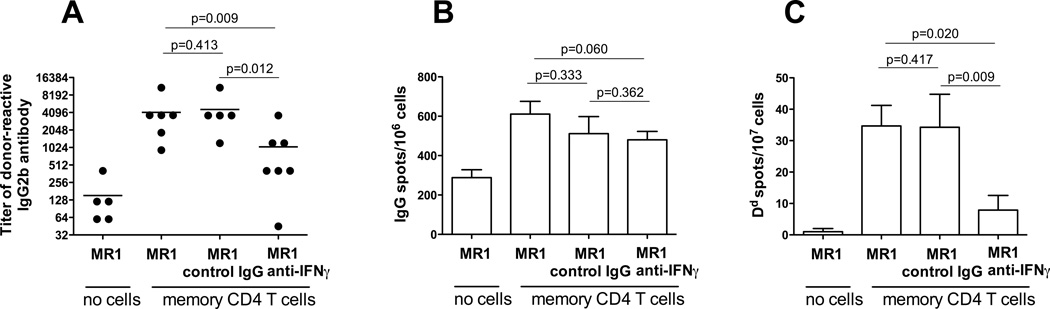

To extend our findings into a more physiological and clinically relevant transplantation model, we performed adoptive transfer of polyclonal donor-reactive memory CD4 T cells into wild type recipients followed by treatment with anti-CD154 mAb MR1 and heart allograft placement. Consistent with our previously published data (24, 32), anti-CD154 mAb decreased the numbers of donor-reactive ASCs and the serum levels of anti-donor IgG Ab in naïve B6 recipients of BALB/c heart allografts (Figure 8 and data not shown). In contrast, donor-reactive CD4 T cells induced strong anti-donor humoral immune responses despite anti-CD154 mAb treatment. Similar to the results observed in CD40−/− recipients, IFNγ neutralization significantly inhibited formation of anti-donor IgG secreting cells and donor-reactive IgG alloAb production (Figure 8). Thus, the effects of IFNγ neutralization on the ability of memory helper T cells to induce CD40-independent humoral immune responses are not limited to TCR transgenic helper T cells and CD40−/− recipients.

Figure 8.

IFNγ neutralization inhibits alloAb production in wild type recipients containing memory CD4 T cells and treated with anti-CD154 Ab. BALB/c-reactive polyclonal memory CD4 T cells were isolated from B6 recipients of BALB/c skin allografts 6 weeks after transplantation and adoptively transferred into naïve wild type B6 mice (5×106/mouse) followed by treatment with anti-CD154 mAb MR, 1 mg i.v. one day prior to BALB/c heart allograft placement. B6 recipients in the control group did not receive memory CD4 T cells and were treated with anti-CD154 Ab. Recipients were sacrificed two weeks after transplantation. N = 5–7 mice/group. A. Serum titers of donor-reactive IgG2b alloAb. The titers of third party-reactive IgG alloAb were ≤ 135. B. The frequencies of total IgG-secreting spleen cells. C. The frequencies of spleen cells secreting donor Dd-binding IgG.

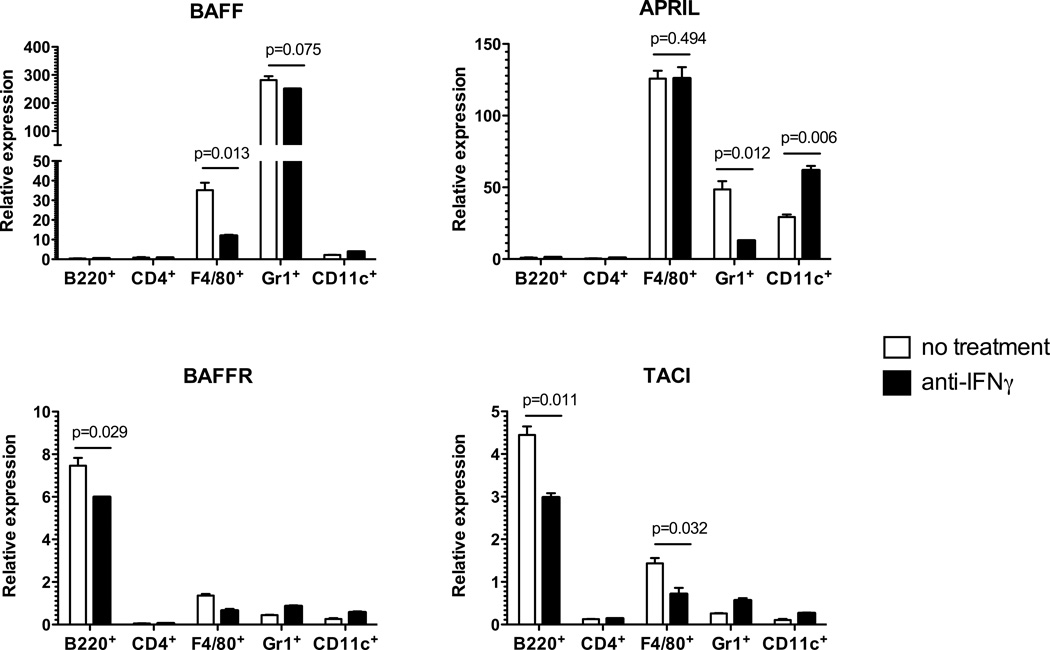

IFNγ neutralization inhibits expression of BAFF, APRIL and their receptors

We have recently reported that neutralizing B cell activating factor (BAFF) and a proliferation-inducing ligand (APRIL) synergized with anti-CD154 mAb to reduce anti-donor alloantibody responses and to prolong heart allograft survival in recipients containing donor-reactive memory CD4 T cells (48). We next tested whether IFNγ secreted by memory CD4 T cells facilitates BAFF/APRIL network signaling in our model. Spleen cell populations were isolated by flow sorting from spleens of CD40−/− heart allograft recipients containing unpolarized memory Mar cells. The analyses of mRNA expression revealed that BAFF was expressed exclusively by Gr1+ and F4/80+ cells (neutrophils and monocyte/macrophages, respectively), while APRIL was expressed by both of these subsets and additionally by CD11c+ dendritic cells (Figure 9, top). Administration of anti-IFNγ mAb selectively inhibited BAFF expression in macrophages and APRIL expression in neutrophils. Unexpectedly, CD11c+ dendritic cells expressed higher levels of APRIL mRNA following IFNγ blockade. As anticipated, BAFFR was predominantly expressed by B220+ cells whereas TACI was expressed by both B220+ cells and F4/80+ cells (Figure 9, bottom). Notably, CD4+ T cells expressed negligible levels of both receptors suggesting that there is no direct effect of BAFF and APRIL on T cell reactivation and helper functions. Treatment with anti-IFNγ mAb significantly inhibited the expression of BAFFR and TACI in B220+ cells and TACI in F4/80+ cells. These findings suggest that the effects of IFNγ on alloAb responses in the absence of CD40 may at least in part be due to the support of BAFF/APRIL signaling.

Figure 9.

The effects of IFNγ neutralization on the expression of BAFF, APRIL, and their receptors. CD40−/− mice were injected with unpolarized memory Mar cells, transplanted with BALB/c cardiac allografts and either treated with anti-IFNγ mAb or left untreated. Spleen cells were harvested on d. 14 after transplantation, and indicated cell subsets were isolated by flow sorting and analyzed by real-time PCR for the expression of BAFF, APRIL, BAFFR, and TACI is outlined in the Methods section. The experiment was performed twice with similar results.

Discussion

The development of donor reactive memory CD4 and CD8 T cells in the course of heterologous immunity undermines the survival of transplanted allografts. Previous studies of heterologous immunity in transplantation exclusively focused on functions of helper and cytotoxic memory T cells characterized by expression of type 1 cytokines, IFNγ and TNFα. However, the human memory T cell repertoire often contains cells programmed to secrete other effector cytokines such as IL-4 and IL-17. The impact of these populations on the course of alloimmune response and transplant rejection has not been previously addressed. Using helper cells with defined specificity for donor antigen, we found that the ability to mount CD40-independent humoral immunity as well as the isotypes, specificity and pathogenicity of the resulting alloAb depend on the differentiation profile of memory CD4 T cells.

Despite recent interest in antibody-mediated allograft tissue injury, the phenotype and functions of helper T cells driving pathogenic alloAb responses remain poorly defined. A specialized follicular helper T cell subset (TFH) responsible for B cell help was described in multiple models of T-dependent humoral immune responses. The initial findings proposed the existence of a separate TFH cell lineage characterized by high expression levels of CXCR5, CD154 and ICOS and by the enhanced ability to produce IL-21 (49). Furthermore, TFH cells form functional memory cells in both mice and humans (50–52). More recent studies indicate that T cells of distinct functional subsets can enter follicular regions and regulate B cell responses, with the Th1 versus Th2 cytokine profile of helper T cells promoting switching to specific Ig isotypes (53, 54). In addition, IL-17 was reported to facilitate antibody production in autoimmune-prone mice (31). In our model, all polarized helper T cell subsets express comparable levels of CXCR5 upon re-activation (data not shown), but we have previously reported that CD40-independent help by memory T cells occurs the absence of follicular germinal centers and therefore may not require helper T cell migration into the follicles (32).

Whether effector and helper functions of Th2 cells are more dependent on CD40/CD154 signaling than those of Th1 or Th17 cells is controversial. On one hand, CD154-deficient Th2 cells induced via direct CD28-costimulation have been shown to initiate productive humoral responses to adenovirus (55). Alternatively, CD154/CD40 blockade ameliorates Th2-mediated diseases such as Graves disease, collagen induced arthritis and hapten induced dermatitis and efficiently prolongs heart allograft survival in Th2-prone STAT4−/− recipients (56). Even more relevant to our study, the ability of Th2 cells to provide help for extrafollicular plasma cell responses is compromised in CD154-deficient mice (57). Our findings suggest that the Th2 help delivered for B cell versus CD8 T cell responses may have distinct requirements for CD40/CD154 interactions.

In contrast to Th1 and Th17 polarized memory T cells, Th2 cells were incapable of inducing high titers of donor-reactive IgG alloantibodies in CD40−/− recipients. This is consistent with the observation that unpolarized memory CD4 T cells in wild type recipients treated with anti-CD154 antibody do not induce high titers of anti-donor IgG1, an isotype typically associated with Th2 immunity (Figure 1). In a recent study, human Th2 and Th17, but not Th1 cells induced antibody isotype switch when co-cultured with naive B cells in vitro (58). The differences between this report and our data are likely due to the additional factors contributing to in vivo versus in vitro T cell-mediated help.

Our data suggest that the measurement of serum anti-donor alloAb by standard techniques may not correspond to the pathologic findings in the graft. Despite comparable titers of donor-reactive alloAb in CD40−/− recipients containing memory Th1 and Th17 cells, the induced Ab differ in their ability to mediate allograft tissue injury (Figure 4). While the adoptive transfer of donor-reactive sera or monoclonal antibodies into immunodeficient recipients usually fails to cause heart allograft failure, C4d deposition is commonly used to assess the pathogenicity of induced alloAb (59). We are currently investigating whether the distinction between Th1- and Th17- induced alloAb in our model may be attributed to differences in alloAb specificity (MHC class I and II and potentially autoantigens), affinity, and isotype distribution (shift from IgG2b and IgG2c to IgG1). While memory CD4 T cells increased anti-donor IgM responses in CD40−/− recipients, the numbers of donor-reactive IgM secreting cells under CD40-deficient conditions were consistently 6–8 fold lower than those in WT recipients regardless of IFNγ neutralization (data not shown). In addition, the pathogenic role of anti-donor IgM alloAb in allograft rejection remains controversial (60–65). Therefore, our future studies will initially focus on donor-reactive IgG alloAb. Instead of complement activation, alloAb induced by Th17 helper cells may bind to endothelial cells and stimulate release of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines, exocytosis of Von Willebrand factor and P-selectin and cell proliferation (35). However, this is unlikely as such functions are mostly described for Ab that cross-link MHC class I molecules; and alloAb of this specificity are not efficiently induced by Th17 memory cells (Figure 5).

Consistent with the finding that the alloAb induced by memory CD4 T cells in a CD40-independent manner are dominated by IgG2b and IgG2c isotypes, these responses were inhibited by anti-IFNγ Ab administration. Importantly, IFNγ neutralization had similar effects in wild type recipients containing polyclonal memory CD4 T cells and treated with anti-CD154 mAb, demonstrating that our findings are not limited to TCR transgenic helper T cells and CD40−/− recipients. Litinskiy et al. (66) have demonstrated that BAFF and APRIL produced by human dendritic cells can induce CD40-independent immunoglobulin class switching in vitro. We recently reported that neutralizing BAFF and APRIL inhibits CD40-independent helper functions of memory CD4 T cells in heart allograft recipients (48). Previous studies in tumor and autoimmunity models demonstrated that IFNγ, among other proinflammatory cytokines, enhances BAFF and APRIL production by various cell types and up-regulates BAFFR expression on B cells (33, 34, 50, 51, 67). In accordance with these findings, our results suggest mechanistic link between IFNγ secreted by memory CD4 T cells and the effects of BAFF/APRIL cytokine signaling in the absence of CD40 (Figure 9). Whereas IFNγ neutralization inhibits expression of BAFF, APRIL and their receptors, we previously showed that blocking BAFF and APRIL decreases the ability of memory CD4 T cells to secrete IFNγ and differentiate into follicular helper T cells (TFH) (48). Therefore, it is possible that B cells stimulated through BCR and BAFFR may further enhance IFNγ secretion by helper T cell thus establishing positive feedback loop resulting in alloAb isotype switching to IgG2b and IgG2c in the absence of CD40/CD154 interactions. In addition, IFNγ may enhance the antigen processing and presentation of donor antigens by B cells, thus stabilizing cognate T/B cell interactions necessary for alloAb production. Studies distinguishing between these possibilities and determining cellular targets of IFNγ in this model are ongoing in our laboratory.

Taken together, our data show that donor-reactive helper memory T cells secreting IFNγ drive generation of pathogenic alloAb under conditions of limited CD40 costimulation. These insights may be used to identify individuals with high risk of de novo alloAb production based on analysis of their memory T cell repertoire prior to transplantation and to design therapies targeting humoral immune responses in T cell sensitized recipients. As several reagents targeting CD40/CD154 costimulatory pathway are being developed and tested in pre-clinical models, our findings may have significant implications for the future use of CD40-directed costimulatory blockade in human transplant patients

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ms. Nina Dvorina for expert technical assistance in this study.

Grant support: This work was supported by 1P01 AI087586 and by R01 AI058088 from the NIAID (AV).

Abbreviations

- ASC

antibody secreting cell

- CSR

class switch recombination

- MFI

mean fluorescence intensity

- MST

mean survival time

- PBST

PBS with 0.025% Tween

- PBS-1%BSA

PBS with 1% bovine serum albumin

- SHM

somatic hypermutation

References

- 1.Claman HN, Chaperon EA, Triplett RF. Thymus-marrow cell combinations. Synergism in antibody production. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1966;122:1167–1171. doi: 10.3181/00379727-122-31353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller JF, Mitchell GF. Cell to cell interaction in the immune response. I. Hemolysin-forming cells in neonatally thymectomized mice reconstituted with thymus or thoracic duct lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1968;128:801–820. doi: 10.1084/jem.128.4.801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bishop GA, Hostager BS. B lymphocyte activation by contact-mediated interactions with T lymphocytes. Curr Opin Immunol. 2001;13:278–285. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(00)00216-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Armitage RJ, Fanslow WC, Strockbine L, Sato TA, Clifford KN, Macduff BM, Anderson DM, Gimpel SD, Davis-Smith T, Maliszewski CR, Clark EA, Smith GA, Grabstein KH, Cosman D, Spriggs MK. Molecular and biological characterization of a murine ligand for CD40. Nature. 1992;357:80–82. doi: 10.1038/357080a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banchereau J, Bazan F, Blanchard D, Briere F, Galizzi JP, van Kooten C, Liu YJ, Rousset F, Saeland S. The CD40 antigen and its ligand. Annual review of immunology. 1994;12:881–922. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.004313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foy TM, Laman JD, Ledbetter JA, Aruffo A, Claassen E, Noelle RJ. gp39-CD40 interactions are essential for germinal center formation and the development of B cell memory. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1994;180:157–163. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.1.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quezada SA, Jarvinen LZ, Lind EF, Noelle RJ. CD40/CD154 interactions at the interface of tolerance and immunity. Annual review of immunology. 2004;22:307–328. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Renshaw BR, Fanslow WC, 3rd, Armitage RJ, Campbell KA, Liggitt D, Wright B, Davison BL, Maliszewski CR. Humoral immune responses in CD40 ligand-deficient mice. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1994;180:1889–1900. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.5.1889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Essen D, Kikutani H, Gray D. CD40 ligand-transduced co-stimulation of T cells in the development of helper function. Nature. 1995;378:620–623. doi: 10.1038/378620a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clatworthy MR. Targeting B cells and antibody in transplantation. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2011;11:1359–1367. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03554.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colvin RB, Smith RN. Antibody-mediated organ-allograft rejection. Nature reviews. Immunology. 2005;5:807–817. doi: 10.1038/nri1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quezada SA, Jarvinen LZ, Lind EF, Noelle RJ. CD40/CD154 interactions at the interface of tolerance and immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:307–328. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wekerle T, Kurtz J, Bigenzahn S, Takeuchi Y, Sykes M. Mechanisms of transplant tolerance induction using costimulatory blockade. Curr Opin Immunol. 2002;14:592–600. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(02)00378-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fishbein TM, Wang L, Benjamin C, Liu J, Tarcsafalvi A, Leytin A, Miller CM, Boros P. Successful tolerance induction under CD40 ligation in a rodent small bowel transplant model: first report of a study with the novel antibody AH.F5. Transplantation. 2002;73:1943–1948. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200206270-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Honey K, Cobbold SP, Waldmann H. CD40 ligand blockade induces CD4+ T cell tolerance and linked suppression. Journal of immunology. 1999;163:4805–4810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Larsen CP, Alexander DZ, Hollenbaugh D, Elwood ET, Ritchie SC, Aruffo A, Hendrix R, Pearson TC. CD40-gp39 interactions play a critical role during allograft rejection. Suppression of allograft rejection by blockade of the CD40-gp39 pathway. Transplantation. 1996;61:4–9. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199601150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Markees TG, Phillips NE, Gordon EJ, Noelle RJ, Shultz LD, Mordes JP, Greiner DL, Rossini AA. Long-term survival of skin allografts induced by donor splenocytes and anti-CD154 antibody in thymectomized mice requires CD4(+) T cells, interferon-gamma, and CTLA4. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1998;101:2446–2455. doi: 10.1172/JCI2703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Larsen CP, Knechtle SJ, Adams A, Pearson T, Kirk AD. A new look at blockade of T-cell costimulation: a therapeutic strategy for long-term maintenance immunosuppression. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:876–883. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirk AD. Crossing the bridge: large animal models in translational transplantation research. Immunol Rev. 2003;196:176–196. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-065x.2003.00081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kean LS, Gangappa S, Pearson TC, Larsen CP. Transplant tolerance in non-human primates: progress, current challenges and unmet needs. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:884–893. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Valujskikh, A Targeting T-cell memory: where do we stand? Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2008;13:344–349. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0b013e3283061126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Valujskikh A, Li XC. Frontiers in nephrology: T cell memory as a barrier to transplant tolerance. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:2252–2261. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007020151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adams AB, Williams MA, Jones TR, Shirasugi N, Durham MM, Kaech SM, Wherry EJ, Onami T, Lanier JG, Kokko KE, Pearson TC, Ahmed R, Larsen CP. Heterologous immunity provides a potent barrier to transplantation tolerance. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2003;111:1887–1895. doi: 10.1172/JCI17477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen Y, Heeger PS, Valujskikh A. In vivo helper functions of alloreactive memory CD4+ T cells remain intact despite donor-specific transfusion and anti-CD40 ligand therapy. J Immunol. 2004;172:5456–5466. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.9.5456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pantenburg B, Heinzel F, Das L, Heeger PS, Valujskikh A. T cells primed by Leishmania major infection cross-react with alloantigens and alter the course of allograft rejection. Journal of immunology. 2002;169:3686–3693. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.7.3686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Welsh RM, Markees TG, Woda BA, Daniels KA, Brehm MA, Mordes JP, Greiner DL, Rossini AA. Virus-induced abrogation of transplantation tolerance induced by donor-specific transfusion and anti-CD154 antibody. J Virol. 2000;74:2210–2218. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.5.2210-2218.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhai Y, Meng L, Gao F, Busuttil RW, Kupiec-Weglinski JW. Allograft rejection by primed/memory CD8+ T cells is CD154 blockade resistant: therapeutic implications for sensitized transplant recipients. Journal of immunology. 2002;169:4667–4673. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.8.4667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McHeyzer-Williams MG. Combinations of interleukins 2, 4 and 5 regulate the secretion of murine immunoglobulin isotypes. Eur J Immunol. 1989;19:2025–2030. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830191109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Snapper CM, Finkelman FD, Paul WE. Regulation of IgG1 and IgE production by interleukin 4. Immunol Rev. 1988;102:51–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1988.tb00741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Snapper CM, Paul WE. Interferon-gamma and B cell stimulatory factor-1 reciprocally regulate Ig isotype production. Science. 1987;236:944–947. doi: 10.1126/science.3107127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hsu HC, Yang P, Wang J, Wu Q, Myers R, Chen J, Yi J, Guentert T, Tousson A, Stanus AL, Le TV, Lorenz RG, Xu H, Kolls JK, Carter RH, Chaplin DD, Williams RW, Mountz JD. Interleukin 17-producing T helper cells and interleukin 17 orchestrate autoreactive germinal center development in autoimmune BXD2 mice. Nature immunology. 2008;9:166–175. doi: 10.1038/ni1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rabant M, Gorbacheva V, Fan R, Yu H, Valujskikh A. CD40-Independent Help by Memory CD4 T Cells Induces Pathogenic Alloantibody But Does Not Lead to Long-Lasting Humoral Immunity. Am J Transplant. 2013;13:2831–2841. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scapini P, Hu Y, Chu CL, Migone TS, Defranco AL, Cassatella MA, Lowell CA. Myeloid cells, BAFF, and IFN-gamma establish an inflammatory loop that exacerbates autoimmunity in Lyn-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 2010;207:1757–1773. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scapini P, Nardelli B, Nadali G, Calzetti F, Pizzolo G, Montecucco C, Cassatella MA. G-CSF-stimulated neutrophils are a prominent source of functional BLyS. J Exp Med. 2003;197:297–302. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li F, Atz ME, Reed EF. Human leukocyte antigen antibodies in chronic transplant vasculopathy-mechanisms and pathways. Curr Opin Immunol. 2009;21:557–562. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fazilleau N, Eisenbraun MD, Malherbe L, Ebright JN, Pogue-Caley RR, McHeyzer-Williams LJ, McHeyzer-Williams MG. Lymphoid reservoirs of antigen-specific memory T helper cells. Nature immunology. 2007;8:753–761. doi: 10.1038/ni1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sallusto F, Geginat J, Lanzavecchia A. Central memory and effector memory T cell subsets: function, generation, and maintenance. Annual review of immunology. 2004;22:745–763. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Honjo K, Yan Xu X, Kapp JA, Bucy RP. Evidence for cooperativity in the rejection of cardiac grafts mediated by CD4 TCR Tg T cells specific for a defined allopeptide. Am J Transplant. 2004;4:1762–1768. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-6143.2004.00596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen Y, Heeger PS, Valujskikh A. In vivo helper functions of alloreactive memory CD4+ T cells remain intact despite donor-specific transfusion and anti-CD40 ligand therapy. J Immunol. 2004;172:5456–5466. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.9.5456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen Y, Demir Y, Valujskikh A, Heeger PS. The male minor transplantation antigen preferentially activates recipient CD4+ T cells through the indirect presentation pathway in vivo. J Immunol. 2003;171:6510–6518. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.12.6510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gorbacheva V, Fan R, Li X, Valujskikh A. Interleukin-17 promotes early allograft inflammation. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:1265–1273. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.091106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang Q, Chen Y, Fairchild RL, Heeger PS, Valujskikh A. Lymphoid sequestration of alloreactive memory CD4 T cells promotes cardiac allograft survival. J Immunol. 2006;176:770–777. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.2.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Valujskikh A, Pantenburg B, Heeger PS. Primed allospecific T cells prevent the effects of costimulatory blockade on prolonged cardiac allograft survival in mice. Am J Transplant. 2002;2:501–509. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2002.20603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Valujskikh A, Heeger P. Enzyme linked immunosorbent spot (ELISPOT) assay for detection of alloreactive cytokine-secreting cells - detailed methods. Graft. 2000;3:250–258. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gorbacheva V, Fan R, Li X, Valujskikh A. Interleukin-17 promotes early allograft inflammation. The American journal of pathology. 2010;177:1265–1273. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.091106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sicard A, Phares TW, Yu H, Fan R, Baldwin WM, 3rd, Fairchild RL, Valujskikh A. The spleen is the major source of antidonor antibody-secreting cells in murine heart allograft recipients. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:1708–1719. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04009.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang QW, Rabant M, Schenk A, Valujskikh A. ICOS-Dependent and -independent functions of memory CD4 T cells in allograft rejection. Am J Transplant. 2008;8:497–506. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.02096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gorbacheva V, Ayasoufi K, Fan R, Baldwin I, WM, Valujskikh A. B cell activating factor (BAFF) and a proliferation inducing ligand (APRIL) mediate CD40-independent help by memory CD4 T cells. The American Journal of Transplantation. 2014 doi: 10.1111/ajt.12984. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.King C, Tangye SG, Mackay CR. T follicular helper (TFH) cells in normal and dysregulated immune responses. Annual review of immunology. 2008;26:741–766. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shen X, Zhang X, Xu G, Ju S. BAFF-R gene induced by IFN-gamma in multiple myeloma cells is related to NF-kappaB signals. Cell Biochem Funct. 2011;29:513–520. doi: 10.1002/cbf.1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nardelli B, Belvedere O, Roschke V, Moore PA, Olsen HS, Migone TS, Sosnovtseva S, Carrell JA, Feng P, Giri JG, Hilbert DM. Synthesis and release of B-lymphocyte stimulator from myeloid cells. Blood. 2001;97:198–204. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.1.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schroder K, Hertzog PJ, Ravasi T, Hume DA. Interferon-gamma: an overview of signals, mechanisms and functions. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;75:163–189. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0603252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pape KA, Kouskoff V, Nemazee D, Tang HL, Cyster JG, Tze LE, Hippen KL, Behrens TW, Jenkins MK. Visualization of the genesis and fate of isotype-switched B cells during a primary immune response. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2003;197:1677–1687. doi: 10.1084/jem.20012065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Toellner KM, Luther SA, Sze DM, Choy RK, Taylor DR, MacLennan IC, Acha-Orbea H. T helper 1 (Th1) and Th2 characteristics start to develop during T cell priming and are associated with an immediate ability to induce immunoglobulin class switching. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1998;187:1193–1204. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.8.1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chirmule N, Tazelaar J, Wilson JM. Th2-dependent B cell responses in the absence of CD40-CD40 ligand interactions. J Immunol. 2000;164:248–255. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.1.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kishimoto K, Dong VM, Issazadeh S, Fedoseyeva EV, Waaga AM, Yamada A, Sho M, Benichou G, Auchincloss H, Jr, Grusby MJ, Khoury SJ, Sayegh MH. The role of CD154-CD40 versus CD28-B7 costimulatory pathways in regulating allogeneic Th1 and Th2 responses in vivo. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:63–72. doi: 10.1172/JCI9586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cunningham AF, Serre K, Mohr E, Khan M, Toellner KM. Loss of CD154 impairs the Th2 extrafollicular plasma cell response but not early T cell proliferation and interleukin-4 induction. Immunology. 2004;113:187–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2004.01951.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Morita R, Schmitt N, Bentebibel SE, Ranganathan R, Bourdery L, Zurawski G, Foucat E, Dullaers M, Oh S, Sabzghabaei N, Lavecchio EM, Punaro M, Pascual V, Banchereau J, Ueno H. Human blood CXCR5(+)CD4(+) T cells are counterparts of T follicular cells and contain specific subsets that differentially support antibody secretion. Immunity. 2011;34:108–121. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Baldwin WM, 3rd, Valujskikh A, Fairchild RL. Antibody-mediated rejection: emergence of animal models to answer clinical questions. Am J Transplant. 2010;10:1135–1142. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03065.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bentall A, Tyan DB, Sequeira F, Everly MJ, Gandhi MJ, Cornell LD, Li H, Henderson NA, Raghavaiah S, Winters JL, Dean PG, Stegall MD. Antibody-mediated rejection despite inhibition of terminal complement. Transplant international : official journal of the European Society for Organ Transplantation. 2014 doi: 10.1111/tri.12396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lietz K, John R, Burke E, Schuster M, Rogers TB, Suciu-Foca N, Mancini D, Itescu S. Immunoglobulin M-to-immunoglobulin G anti-human leukocyte antigen class II antibody switching in cardiac transplant recipients is associated with an increased risk of cellular rejection and coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2005;112:2468–2476. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.485003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Marcen R, Ting A, Taylor CJ, Miach PJ, Chapman JR, Morris PJ. Immunoglobulin class and specificity of lymphocytotoxic antibodies after kidney transplantation. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 1988;3:809–813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.McAlister CC, Gao ZH, McAlister VC, Gupta R, Wright JR, Jr, MacDonald AS, Peltekian K. Protective anti-donor IgM production after crossmatch positive liver-kidney transplantation. Liver transplantation : official publication of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the International Liver Transplantation Society. 2004;10:315–319. doi: 10.1002/lt.20062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McCalmon RT, Jr, Tardif GN, Sheehan MA, Fitting K, Kortz W, Kam I. IgM antibodies in renal transplantation. Clinical transplantation. 1997;11:558–564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stastny P, Ring S, Lu C, Arenas J, Han M, Lavingia B. Role of immunoglobulin (Ig)-G and IgM antibodies against donor human leukocyte antigens in organ transplant recipients. Human immunology. 2009;70:600–604. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2009.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Litinskiy MB, Nardelli B, Hilbert DM, He B, Schaffer A, Casali P, Cerutti A. DCs induce CD40-independent immunoglobulin class switching through BLyS and APRIL. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:822–829. doi: 10.1038/ni829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fu L, Lin-Lee YC, Pham LV, Tamayo A, Yoshimura L, Ford RJ. Constitutive NF-kappaB and NFAT activation leads to stimulation of the BLyS survival pathway in aggressive B-cell lymphomas. Blood. 2006;107:4540–4548. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.