Abstract

Background

Providing needles to people who inject drugs is a well-proven public health response to the transmission of HIV and other blood borne viruses. Despite over a quarter of a century of research, new concerns about potential unintended negative consequences of needle distribution continue to emerge. Specifically, a claim was recently made that the introduction of pharmacy sales of needles was followed by an increase in overdoses in pharmacy parking lots. If true, this would have serious implications for the design of needle access programs, particularly those involving pharmacy sales of needles.

Methods

We examine spatial relationships between drug-related deaths and pharmacies in Los Angeles County (population 9·8 million) before and after the 2007 enactment of a California law allowing pharmacy sales of needles without a prescription. 7,049 drug related deaths occurred in Los Angeles county from 2000-2009 inclusive. 4,275 of these deaths could be geocoded, and were found to be clustered at the census tract level.

Results

We used three methods to examine spatial relationships between overdose death locations and pharmacy locations for two years on either side of the enactment of the pharmacy sales law, and found no statistically significant changes. Among the 711 geocodable deaths occurring in the two years following the change in law, no death was found to occur within 50 meters of a pharmacy which sold needles.

Conclusion

These results are consistent with prior studies which suggest pharmacy sales of needles improve access to needles without causing increased harms to the surrounding community.

Keywords: Overdose, pharmacy, needle distribution, people who inject drugs, HIV

1. INTRODUCTION

On May 18, 2012, WNEP-TV in Williamsport Pennsylvania (an ABC affiliate) reported that local police and the District Attorney's office had claimed that following Pennsylvania's legalization of the sale of needles without a prescription in 2009, the number of overdoses occurring in the vicinity of pharmacies in Williamsport had dramatically increased (Hamill, 2012).

Pharmacy sales of needles are an important component of efforts to reduce HIV and viral hepatitis transmission among people who inject drugs (Cooper et al., 2010; Fuller et al., 2007; Garfein et al., 2010; MacDonald et al., 2003; Pouget et al., 2005; Riley et al., 2010; Rudolph et al., 2010; Wodak and Cooney, 2006), particularly in jurisdictions where gaining legal and social approval for dedicated needle exchanges is difficult or impossible (Broadhead et al., 1999; Davidson and Howe, 2014; Lurie et al., 1998; Tempalski et al., 2007). Further, pharmacies provide some potential advantages over needle exchanges, including broader operating hours and less concern on the part of drug users about being ‘outed’ as a drug user by using the service (Gostin, 1998; Rich et al., 1999).

Over the past quarter of a century, researchers have systematically tested and refuted community concerns about unintended negative consequences of needle provision to drug users, ranging from increases in crime (Galea et al., 2001; Stopka et al., 2014) through to street-disposed needles (Kral et al., 2004) and needle stick injuries (Stopka et al., 2010). However, to our knowledge, there have been no previous claims that pharmacy sales of needles were associated with spatially-proximate overdoses, and there are no research studies of which we are aware that have examined relationships between pharmacy sales of needles and spatially-proximate overdose.

Overdose, by far the largest cause of drug-related deaths (Bargagli et al., 2001; Degenhardt et al., 2009; Evans et al., 2012; Stoové et al., 2008), is also the second largest cause of accidental death from any cause in the United States, having eclipsed motor vehicle accident deaths in 2011 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014). If, as suggested, pharmacy sales of needles are associated with increases in the frequency, or changes in the geographic distribution of overdoses, this would have serious implications for the future of this otherwise well-established and effective HIV prevention intervention.

To examine the spatial relationships between drug-related deaths and pharmacies selling needles without a prescription, we use data from a large US county (Los Angeles County, California, population 9·8 million in 2010) pre- and post-implementation of a California law, which legalized the sale of needles without a prescription in pharmacies. We hypothesized: 1) that drug-related deaths would be geographically clustered at the census tract level in Los Angeles County, and 2) that locations of pharmacies would not become spatially associated with locations of drug-related deaths after the enactment of the law allowing pharmacy sales of needles without prescription. To examine these hypotheses, we use ten years of Los Angeles County Coroner data on drug-related fatalities in Los Angeles County from 2000 to 2009, covering the period before and after the legalization of pharmacy sales of needles in 2007, and data from a survey of pharmacy sales of needles conducted in Los Angeles County in late 2007.

2. METHODS

As used in this paper, ‘drug-related deaths’ are defined as accidental deaths caused by intake of drugs excluding alcohol. Deaths proximate to drug intake, such as an injury death from a motor vehicle accident following drug intoxication, or a death from a disease such as HIV acquired through drug use, are not included as drug related deaths for the purposes of this paper. Using this definition, almost all ‘drug-related deaths’ are overdose deaths, with the remainder being adverse effects of medically prescribed and over-the-counter drugs. We also limited our analysis to unintentional deaths, defined as deaths determined by the Coroner to be accidental or undetermined in nature (i.e., excluding deaths determined to be homicide, suicide, or due to natural causes), as we deemed non-accidental deaths to be unrelated to the questions posed by this paper.

2.1 Coroner data methods

Los Angeles Coroner data for the period January 2000 to December 2009 inclusive was provided by the Injury and Violence Prevention Program (IVPP) of the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health. Data included address of event (i.e. the address at which the decedent was found), cause and mode of death (e.g., ‘drug related’; ‘accidental’), a short description of the scene provided by a scene investigator, and post-mortem toxicology. Using a validated algorithm developed by IVPP, we sorted the 50,401 non-natural deaths which occurred in Los Angeles County during this period into ‘drug related deaths’ and ‘other.’ The algorithm, described in detail elsewhere (Sternfeld et al., 2010), searches for matches in toxicology and case files to a validated list of 171 keywords. 8,102 drug-related deaths were found during the period 2000-2009 inclusive. We then removed deaths determined by the Los Angeles Coroner to be homicide (n=37) or suicide (n=1,016), leaving 7,049 deaths.

Los Angeles County Coroner files include three fields connected to the location of the death: a residential address field containing the home address of the decedent; an “event address” field containing the address at which death had occurred; and a “death place” field containing a one-word description of the nature of the location of death (e.g., “hotel” or “hospital”). In 12 of the 7,049 accidental drug related death files, none of these fields was present; the remainder had at least one of these three fields. In order to perform geospatial analysis, we extracted all files where the “event address” field was not empty, in addition to all files where the residential address was not empty and the “death place” field contained the value “residence” or “home.” 4,321 accidental drug-related deaths met these criteria (61% of 7,049). These deaths were geocoded against US Census Tiger Line data (U.S. Census Bureau, 2014) using the PostGIS Tiger Geocoder, which provides a latitude and longitude for any provided address in the United States along with a score indicating the quality of the match (Refractions Research, 2013a). Addresses with a score indicating low certainty or no match at all were manually reviewed and geocoded by a research assistant. The main reason for lack of match was the use of ‘descriptive’ death locations, such as “under I-5 freeway on-ramp between 5th and 6th streets”, rather than a standardized street address. 419 cases required manual geocoding. In 46 of these 419 cases the available data were insufficient to allow determination of the location of death. This process left us with 4,275 geocoded accidental drug-related deaths occurring in Los Angeles County occurring during the years 2000-2009 inclusive. Finally, to check deaths occurring at geocoded locations were not demographically dissimilar from those that could not be geocoded, we compared ages and ethnicities of decedents (gender was not available in our dataset), and found no differences.

2.2 Pharmacy data methods

California law was changed to allow individual counties to authorize the sale of needles through pharmacies without a prescription on January 1, 2005 (Stopka et al., 2010). Los Angeles County authorized such sales in early 2007 (Cooper et al., 2010). In late 2007, we conducted a survey of 171 pharmacies in the three Los Angeles county ‘service planning areas’ (SPAs) with the highest prevalence of injection-related HIV/AIDS to determine if they sold needles without a prescription. SPAs are administrative boundaries used primarily by the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health to plan and manage health service delivery across the County (Los Angeles County, 2014).

Pharmacy data was collected as part of a study that examined the impact of SB1159 on HIV prevention among people who inject drugs. Methods are described in more detail elsewhere (Cooper et al., 2010). Briefly, a list of licensed retail pharmacies as of February 1, 2007 was obtained from the California Board of Pharmacy. As Los Angeles County has over 1,700 retail pharmacies, surveying was limited to areas determined to have the highest numbers of people who inject drugs. This was determined by selecting the three (of eight total) SPAs with the highest prevalence of injection-related HIV (total population ~3·9 million), then selecting the 33 ZIP codes within the three SPAs with the highest number of individuals in treatment for drug use. A list of all 211 retail pharmacies present in these ZIP codes was generated. These pharmacies were sent an informational letter and received a follow-up call one week later. Pharmacists at 171 (81%) pharmacies were successfully interviewed, 47 (27%) of whom reported selling needles without a prescription). Interviews included questions on knowledge of and participation in the program allowing non-prescription sales of needles to drug users.

2.3 Spatial Analysis

To test Hypothesis 1, we utilized all 4,275 geocoded deaths. To test Hypothesis 2, we limited our analysis to the 853 geocoded deaths occurring in the two years prior to the enactment of SB1159 in Los Angeles County (2005-2006), and the 711 geocoded deaths occurring in the two years following its enactment (2008-2009).

The first step in the analysis was to identify whether or not overdose deaths in Los Angeles County were clustered at the level of the census tract. Second, we sought to identify if any pattering of observed clustering could be explained by proximity to location of pharmacies. We use three methods to examine whether or not pharmacy locations explain patterns of overdose deaths. To guide our analyses, we created thematic maps that show the spatial distribution of drug-related deaths aggregated to the Census tract. We then used three spatial approaches to analyze the pharmacy and death data.

To test hypothesis 1, we used indicators of spatial association to evaluate the existence of clusters in the spatial patterning of overdose deaths (Anselin et al., 1996, 2006). Global spatial autocorrelation is a measure of the overall clustering of the data. For the univariate tests, we conducted a global test (Moran's I) followed by a set of local tests (Local Indicator of Spatial Association, or LISA) (Anselin, 1995). A +1 value of a global Moran I indicates strong positive spatial autocorrelation (i.e., clustering of similar values), 0 indicates random spatial ordering, and -1 indicates strong negative spatial autocorrelation (i.e., a checkerboard pattern). The global test hypothesizes that there is a spatially random pattern of drug-related deaths among census tracts, which is rejected in the presence of any local spatial clustering. To see exactly where this local clustering occurs, LISA tests are used (Anselin, 1995). In a univariate LISA test, a finding of significant clustering for a group of neighboring census tracts suggests that values for observed drug-related deaths are too similar across these tracts to have occurred by chance, providing significant evidence for rejecting the null hypothesis of spatial randomness.

The association among locations for either the local (LISA) or global (Moran's I) tests is defined using a spatial weights matrix. The weights matrix describes for each location all of the closest neighboring locations and is derived either from a distance matrix that contains distances between all possible pairs of locations, or a contiguity matrix that assesses common boundaries. We used a queen weights contiguity matrix that defines a location's neighbors as those with either a shared border or vertex/corner. We identify significant clusters by noting the individual tracts that make up the “core” of these clusters and the neighbors of these cores. A randomization approach was used to generate a spatially random reference distribution to assess the likelihood of observing clusters due to chance. Whether or not this value is statistically significant is assessed by comparing the actual value to the value calculated for the same location by randomly reassigning the data among all the areal units and recalculating the values each time. Spatial analyses were conducted using GeoDa software (GeoDa Center for geospatial analysis and computation, Arizona State University, 2014) and results were mapped using ArcGIS (ESRI, 2011).

To test Hypothesis 2, we used three methods to explore the spatial relationship between locations of pharmacies and locations of drug-related deaths. The first method was a proximity analysis conducted using data from 2005-2006 and 2008-2009. We restricted the data to the 853 geocodeable drug-related deaths that occurred in Los Angeles County during the two year period 2005-2006, and the 711 geocodeable deaths that occurred during the two year period 2008-2009. We calculated the mean number of drug-related deaths in a census tract for the two time periods: 2005-2006 (prior to SB1159 enactment) and 2008-2009 (post SB1159 enactment), leaving out 2007 as exact dates of enactment for each pharmacy were not available. We then tested to see if the mean number of drug-related deaths at the tract level varied in the two time periods, controlling for tract level population. We assessed the significance by using a t-test to compare means of drug-related deaths in a tract. We then used ArcGIS software to map locations of deaths and pharmacies.

In the second approach, we calculated the distance from every surveyed pharmacy to the nearest drug-related death for two time periods: 2005-2006 (prior to SB1159 enactment) and 2008-2009 (post SB1159 enactment), leaving out 2007 as exact dates of enactment for each pharmacy were not available. Pharmacies were then grouped into two groups: those who reported selling needles after SB1159 was enacted and those that did not. For each time period, we calculated the distance from each pharmacy to the closest death that occurred during the time period. As death distances were not normally distributed (determined using the Shapiro-Wilk test for normality (Shapiro and Wilk, 1965)), we used a Mann-Whitney U test to compare distances-to-death for pharmacies that did sell needles with those who did not during the post-SB1159 period. We then repeated the test for the pre-SB1159 period. Distance calculations were made using PostGIS (Refractions Research, 2013b); Shapiro-Wilk and Mann-Whitney U tests were conducted using R (R Development Core Team, 2011).

In the final approach, we sought to determine if any drug-related deaths occurred ‘in a parking lot’ by looking at whether any deaths occurred within a 50 meter buffer of pharmacy locations, before and after the enactment of SB1159 in Los Angeles, using the distances calculated from every pharmacy to the nearest death described above.

2.4 Ethical approval

Study procedures relating to collection of pharmacy sales data were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at California State University Dominguez Hills and the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects, Health and Human Services Agency, State of California. Use of Los Angeles Coroner data was determined to be exempt from review by the IRB of the University of California, San Diego.

3. RESULTS

There were 7,049 drug-related deaths determined to be accidental or undetermined in Los Angeles County from 2000-2009 inclusive. The overall rate of drug-related deaths in Los Angeles County ranged from 9·62 per 100,000 residents in 2000 to 7·92 in 2009 (the most recent year in our dataset).

3.1 Geographic distribution of drug-related deaths

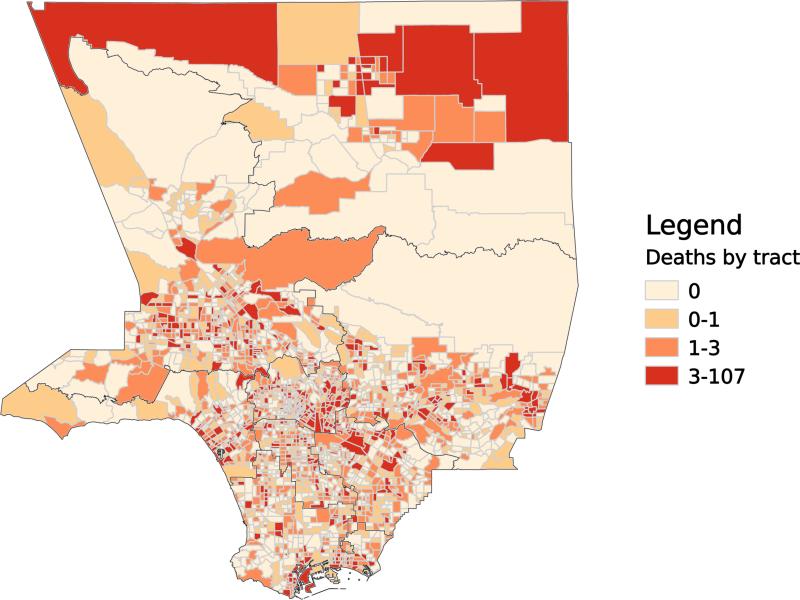

Drug-related deaths occurred in 1,524 (65%) of Los Angeles’ 2,343 census tracts (range 0 to 107 deaths) from 2000 to 2009 (Figure 1). Overall, the mean number of deaths per tract was 1·8 with a standard deviation of 3·6. The median number of deaths per census tract was 1·0, with an interquartile range of 0 and 3. Figure 1 displays the quartile distribution of all geocodeable drug-related deaths by census tract in LA County, with the darkest shade corresponding to the highest quartile. SPA outlines are overlaid in black. A visual inspection of this map suggests a spatial clustering of drug-related deaths throughout Los Angeles County, particularly in SPA 4, which contains the downtown/skid-row area. This observation is confirmed by a strong positive and significant Moran's I of 0·43, with an associated standard normal z-value of 4·35 (p =0·002). Next, we sought to identify local spatial clusters of drug-related deaths.

Figure 1.

Quartile distribution of counts of geocodable drug-related deaths in Los Angeles County, California USA. Faint lines are census tract boundaries. Black lines are Service Planning Area (SPA) boundaries.

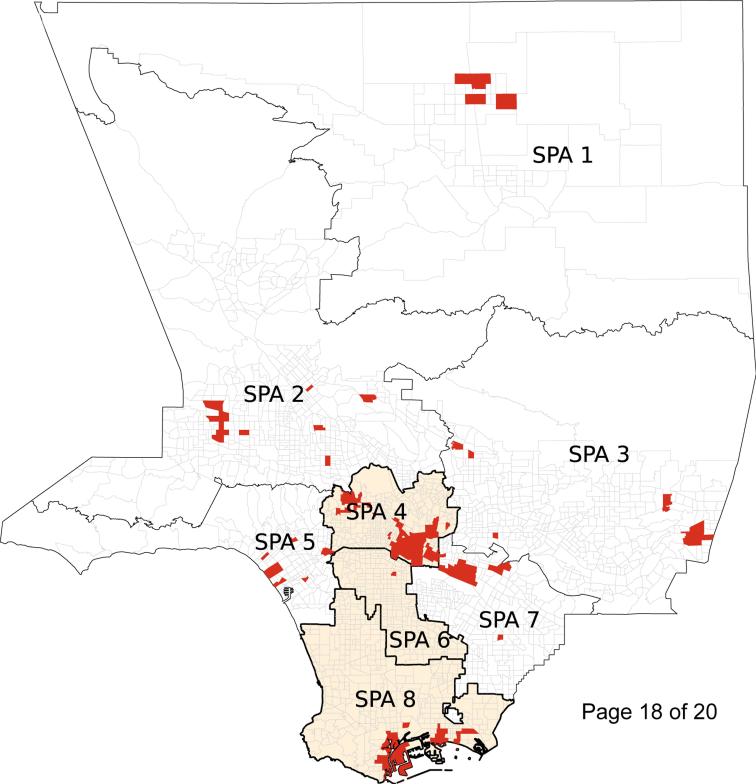

In Los Angeles County we found 133 cluster cores (Figure 2), meaning that there are 133 census tracts (out of 2,343 total) with higher than average numbers of drug-related deaths that are neighbored by tracts that also have higher than average numbers of such deaths. The actual extent of a clustering includes the core and the surrounding neighbors as defined by the weights matrix. The weights matrix was created with neighbors defined as census tracts that border each other on any side. The largest local spatial cluster includes 37 positively correlated cluster cores that share a boundary. There were 437 drug-related deaths in these cluster cores and 115 deaths in neighboring tracts, which together represent 13% of all deaths (552/4,275) in the study period (2000-2009). The largest cluster is in SPA 4.

Figure 2.

Drug related death cluster cores, Los Angeles County, California USA. Faint lines are census tract boundaries. Black lines are Service Planning Area (SPA) boundaries. Light shaded area shows the three Service Planning Areas (SPAs) in which pharmacy surveys took place.

3.2 Distance to nearest death

A Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare distances for pharmacies who did and did not sell needles after 2007 for both pre-2007 and post-2007 time periods. In both cases the p value was > 0·05 (pre-2007: W = 2,803·5, p-value = 0·7631; post-2007: W = 2,970·5, p-value = 0·7818) meaning there were no statistically significant differences in the medians of the two groups and hence no statistically significant association between selling needles and distance to accidental drug-related deaths.

3.3 Deaths in ‘parking lots’

Using the distance calculations described above, we then looked for any instances where a death had occurred within 50 meters of a pharmacy (i.e., where there was any possibility the death might have occurred in a pharmacy parking lot or on pharmacy property. Three deaths occurred within 50 meters of a pharmacy, two prior to the enactment of SB1159, and one after SB1159 but in the vicinity of a pharmacy that did not sell needles. That is, no accidental drug-related deaths are known to have occurred within 50 meters of any pharmacy which sold needles in the two years following enactment of SB1159.

4. DISCUSSION

This spatial analysis of drug-related deaths and pharmacy data at the census tract level showed that the geographic distribution of deaths was not spatially random during the study period. In a large, diverse urban area, with locations of 1,564 accidental drug-related deaths available for two years on either side of the enactment of a law allowing pharmacy sales of needles without prescription, none of our analytic approaches showed a statistically significant association between death locations and the locations of pharmacies where needles were sold. In the case of Los Angeles, allowing the sale of needles through pharmacies does not appear to have resulted in either an increase in deaths or a measurable change in the geographic distribution of deaths. Further, among the 711 geocodeable accidental drug-related deaths which occurred in the county in the two years since pharmacy sales became legal, we could not find a single instance of a death occurring within 50 meters of a pharmacy known to sell needles.

This study has a number of potential limitations. First, nearly 39% of the accidental drug related deaths which occurred in Los Angeles County in 2000-2009 could not be included in our analysis due to lack of usable location data. However, there is no reason to believe that there is differential bias with respect to this missing data, and we found no difference between the demographic characteristics of decedents with and without usable location data. We cannot think of any reason why there would be more or less missing data in geographic relation to pharmacies.

Second, we were only able to examine drug-related fatalities rather than the far more common non-fatal overdoses (Warner-Smith et al., 2001). One key factor increasing the likelihood of an overdose event ending in death is being out of sight of others (Davidson, 1999; Davidson et al., 2003). As such, an individual who experiences overdose or another drug-related emergency in a public space such as a pharmacy parking lot may be more likely to be noticed by a passer-by than (for example) someone overdosing alone behind closed doors, and hence the event may be less likely to result in death. Our analysis may therefore be missing an increase in non-fatal overdose events in the vicinity of pharmacies. We suggest, however, that changes in public policy (in this case the sale of needles through pharmacies) which leads people who use drugs to do so in locations where life-saving intervention is more likely in the event of an overdose is a positive rather than negative outcome from a public health and humanitarian perspective.

Third, our analysis was conducted using data from a county where pharmacies are not the sole source of needles. During the analysis period, Los Angeles had eight agencies that conduct needle exchange from approximately thirty locations, distributing an average of 1·3 million needles per year (Simon et al., 2009). While this volume of needles is completely insufficient for the blood-borne virus prevention needs of a county with a population the size of Los Angeles’ (Lurie et al., 1998; Remis et al., 1998), the existence of needle exchange programs providing free needles may considerably reduce the demand for needles from pharmacies. By contrast, Williamsport Pennsylvania, the town mentioned in the introduction to this article, has no needle exchange (there are only two needle exchanges in Pennsylvania, one in Pittsburgh and one in Philadelphia, both over three hours drive from Williamsport). Prior to pharmacy sales of needles therefore, people who use drugs in Williamsport would have acquired needles through a combination of diversion (e.g., acquiring needles intended for people with diabetes or other medical uses) and delivery (i.e., individuals making the trip to other cities with needle exchanges and bringing back a regular supply) – in short, needles can enter the community in geographically and temporally diverse ways. The existence of needle exchange programs in Los Angeles may have led to less demand for needles through pharmacies, attenuating any hypothesized local impact when compared to locations such as Williamsport, where pharmacies currently represent the only legal source of needles. If true, this suggests increasing the number of sources of needles is an appropriate response to any undesired spatial clustering of drug-related activity.

In conclusion, we show that in a large urban location with a high rate of accidental drug-related deaths, the introduction of a new method of needle distribution (pharmacy sales) was not associated with either an increase in deaths or a change in the geographical distribution of deaths. This result is in line with other studies that have documented that fears associated with expanded syringe access, such as increased crime, drug use, and even needle stick injuries are unwarranted (Des Jarlais et al., 1995; Guydish et al., 1993; Marx et al., 2000; Stopka et al., 2010). Life-saving interventions such as needle exchange programs, over-the-counter pharmacy sales of needles, and overdose prevention programs for people who inject drugs are often political controversial and unpopular, yet are desperately needed to prevent overdose deaths, HIV and HCV transmissions. More studies that document the absence of unintended negative consequences of these programs are needed to speed the dissemination of these programs.

Highlights.

* California law now allows pharmacies to sell needles without prescription.

* We examined spatial relationships between drug-related deaths and pharmacies in Los Angeles before and after the change in law.

* No statistically significant changes to the distribution or number of overdose deaths occurred.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Michèle Thorsen for her assistance in geocoding death locations, Erin Cooper and Chaka Dodson for their efforts surveying pharmacies, and Isabelle Sternfeld from the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health, Injury and Violence Prevention Program, for assistance accessing and interpreting coroner data.

Role of funding source

This study was funded by the California Department of Public Health Office of AIDS, Grant 06-55589, NIH/NIDA K01-DA032443, NIH L60-MD005619, NIH/NIDA R01-DA023377 and NIH/NIDA R01-DA027689. No funding source had any role in any aspect of this paper.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors

AK came up with the original study question. PJD, AM, AK, AL, and RB designed an analytic approach to answer the question. PJD and AM carried out the analysis. PJD and AM wrote the first draft of the paper. All authors contributed to the refinement and completion of the paper.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Peter J. Davidson, Division of Global Public Health Department of Medicine University of California, San Diego San Diego CA USA

Alexis Martinez, Department of Sociology San Francisco State University San Francisco CA USA.

Alexandra Lutnick, Urban Health Program RTI International San Francisco, CA USA.

Alex H. Kral, Urban Health Program RTI International San Francisco, CA USA

Ricky N. Bluthenthal, Department of Preventive Medicine Institute for Prevention Research Keck School of Medicine University of Southern California Los Angeles, CA USA

REFERENCES

- Anselin L. Local Indicators of Spatial Association—LISA. Geogr. Anal. 1995;27:93–115. [Google Scholar]

- Anselin L, Bera AK, Florax R, Yoon MJ. Simple diagnostic tests for spatial dependence. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 1996;26:77–104. [Google Scholar]

- Anselin L, Syabri I, Kho Y. GeoDa: an introduction to spatial data analysis. Geogr. Anal. 2006;38:5–22. [Google Scholar]

- Bargagli AM, Sperati A, Davoli M, Forastiere F, Perucci CA. Mortality among problem drug users in Rome: an 18-year follow-up study, 1980–97. Addiction. 2001;96:1455–1463. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.961014559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadhead RS, Van Hulst Y, Heckathorn DD. The impact of a needle exchange‘s closure. Public Health Rep. 1999;114:439–447. doi: 10.1093/phr/114.5.439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Injury Prevention and Control: Data and Statistics (WISQARS) [WWW Document] 2014 URL http://www.cdc.gov/ncipc/wisqars.

- Cooper EN, Dodson C, Stopka TJ, Riley ED, Garfein RS, PhD RNB. Pharmacy participation in non-prescription syringe sales in Los Angeles and San Francisco Counties, 2007. J. Urban Health. 2010;87:543–552. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9483-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson P. Circumstances Of Death: An Assessment Of The Viability Of Using Non-Toxicological Coronial Data To Investigate Opiate Overdose Risk Factors. National Center For Research Into The Prevention Of Drug Abuse; Perth, Western Australia: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson PJ, Howe M. Beyond NIMBYism: Understanding community antipathy toward needle distribution services. Int. J. Drug Policy. 2014;25:624–632. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson PJ, McLean RL, Kral AH, Gleghorn AA, Edlin BR, Moss AR. Fatal heroin-related overdose in San Francisco, 1997–2000: a case for targeted intervention. J. Urban Health. 2003;80:261–273. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jtg029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L, Randall D, Hall W, Law M, Butler T, Burns L. Mortality among clients of a state-wide opioid pharmacotherapy program over 20 years: risk factors and lives saved. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;105:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Des Jarlais DC, Paone D, Friedman SR, Peyser N, Newman RG. Regulating controversial programs for unpopular people: methadone maintenance and syringe exchange programs. Am. J. Public Health. 1995;85:1577–1584. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.11.1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ESRI . ArcGIS 10. Environmental Systems Research Institute, Inc.; Redlands CA.: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Evans JL, Tsui JI, Hahn JA, Davidson PJ, Lum PJ, Page K. Mortality among young injection drug users in San Francisco: a 10-year follow-up of the UFO Study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2012;175:302–308. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller CM, Galea S, Caceres W, Blaney S, Sisco S, Vlahov D. Multilevel community-based intervention to increase access to sterile syringes among injection drug users through pharmacy sales in New York City. Am. J. Public Health. 2007;97:117–124. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.069591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Ahern J, Fuller C, Freudenberg N, Vlahov D. Needle exchange programs and experience of violence in an inner city neighborhood. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2001;28:282–288. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200111010-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garfein RS, Stopka TJ, Pavlinac PB, Ross A, Haye BK, Riley ED, Bluthenthal RN. three years after legalization of nonprescription pharmacy syringe sales in California: where are we now? J. Urban Health. 2010;87:576–585. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9463-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GeoDa Center for geospatial analysis and computation, Arizona State University [1.27.14];GeoDa Center for geospatial analysis and computation [WWW Document] 2014 URL http://geodacenter.asu.edu/

- Gostin LO. The legal environment impeding access to sterile syringes and needles: the conflict between law enforcement and public health. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. Hum. Retrovirol. 18 Suppl. 1998;1:S60–70. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199802001-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guydish J, Bucardo J, Young M, Woods W, Grinstead O, Clark W. Evaluating needle exchange: are there negative effects? AIDS Lond. Engl. 1993;7:871–876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill J. Needles Leading to Drug Overdoses? WNEP.com.; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kral AH, Anderson R, Flynn NM, Bluthenthal RN. Injection risk behaviors among clients of syringe exchange programs with different syringe dispensation policies. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2004;37:1307–1312. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000127054.60503.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Los Angeles County [1.27.14];Los Angeles County GIS Data Portal: Service Planning Areas (SPA) – 2012 [WWW Document] 2014 URL http://egis3.lacounty.gov/dataportal/2012/03/01/service-planning-areas-spa-2012/

- Lurie P, Jones TS, Foley J. A sterile syringe for every drug user injection: how many injections take place annually, and how might pharmacists contribute to syringe distribution? J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. Hum. Retrovirology 18 Suppl. 1998;1:S45–51. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199802001-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald M, Law M, Kaldor J, Hales J, Dore J, G. Effectiveness of needle and syringe programmes for preventing HIV transmission. Int. J. Drug Policy. 2003;14:353–357. [Google Scholar]

- Marx MA, Crape B, Brookmeyer RS, Junge B, Latkin C, Vlahov D, Strathdee SA. Trends in crime and the introduction of a needle exchange program. Am. J. Public Health. 2000;90:1933–1936. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.12.1933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouget ER, Deren S, Fuller CM, Blaney S, McMahon JM, Kang S-Y, Tortu S, Andia JF, Des Jarlais DC, Vlahov D. Receptive syringe sharing among injection drug users in Harlem and the Bronx during the New York State Expanded Syringe Access Demonstration Program. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2005;39:471–477. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000152395.82885.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team . R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Refractions Research . Tiger Geocoder. Refractions Research; Victoria, BC.: 2013a. [Google Scholar]

- Refractions Research . PostGIS 2.0.4. Refractions Research; Victoria, BC.: 2013b. [Google Scholar]

- Remis RS, Bruneau J, Hankins CA. Enough sterile syringes to prevent HIV transmission among injection drug users in Montreal? J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. Hum. Retrovirol. 18 Suppl. 1998;1:S57–59. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199802001-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich JD, Strong L, Towe CW, McKenzie M. Obstacles to needle exchange participation in Rhode Island. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 1999;21:396–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley ED, Kral AH, Stopka TJ, Garfein RS, Reuckhaus P, Bluthenthal RN. Access to sterile syringes through San Francisco pharmacies and the association with hiv risk behavior among injection drug users. J. Urban Health. 2010;87:534–542. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9468-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph AE, Crawford ND, Ompad DC, Benjamin EO, Stern RJ, Fuller CM. Comparison of injection drug users accessing syringes from pharmacies, syringe exchange programs, and other syringe sources to inform targeted HIV prevention and intervention strategies. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2010;50:140–147. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2010.09193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro SS, Wilk MB. An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples). Biometrika. 1965;52:591–611. [Google Scholar]

- Simon SD, Long A, Bluthenthal R. The City And County Of Los Angeles. Los Angeles County: 2009. Harm Reduction And Syringe Exchange Programs. [Google Scholar]

- Sternfeld I, Perras N, Culross PL. Development of a coroner-based surveillance system for drug-related deaths in Los Angeles County. J. Urban Health. 2010;87:656–669. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9455-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoové MA, Dietze PM, Aitken CK, Jolley D. Mortality among injecting drug users in Melbourne: a 16-year follow-up of the Victorian Injecting Cohort Study (VICS). Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;96:281–285. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stopka TJ, Garfein R, Riley E, Rose V, Kral A, Ross A, Bluthenthal R. SB 1159 Report: An Evaluation of Over-the-Counter Sale of Sterile Syringes in California. Sacremento. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- Stopka TJ, Geraghty EM, Azari R, Gold EB, DeRiemer K. Is crime associated with over-the-counter pharmacy syringe sales? Findings from Los Angeles, California. Int. J. Drug Policy. 2014;25:244–250. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tempalski B, Flom PL, Friedman SR, Jarlais DCD, Friedman JJ, McKnight C, Friedman R. Social and political factors predicting the presence of syringe exchange programs in 96 US metropolitan areas. Am. J. Public Health. 2007;97:437–447. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.065961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Census Bureau US. [1.27.14];TIGER/Line Shapefiles [WWW Document] 2014 URL https://www.census.gov/geo/maps-data/data/tiger-line.html.

- Warner-Smith M, Darke S, Lynskey M, Hall W. Heroin overdose: causes and consequences. Addiction. 2001;96:1113–1125. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.96811135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wodak A, Cooney A. Do needle syringe programs reduce hiv infection among injecting drug users: a comprehensive review of the international evidence. Subst. Use Misuse. 2006;41:777–813. doi: 10.1080/10826080600669579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]