Abstract

Arterial blood O2 levels are detected by specialized sensory organs called carotid bodies. Voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCCs) are important for carotid body O2 sensing. Given that T-type VGCCs contribute to nociceptive sensation, we hypothesized that they participate in carotid body O2 sensing. The rat carotid body expresses high levels of mRNA encoding the α1H-subunit, and α1H protein is localized to glomus cells, the primary O2-sensing cells in the chemoreceptor tissue, suggesting that CaV3.2 is the major T-type VGCC isoform expressed in the carotid body. Mibefradil and TTA-A2, selective blockers of the T-type VGCC, markedly attenuated elevation of hypoxia-evoked intracellular Ca2+ concentration, secretion of catecholamines from glomus cells, and sensory excitation of the rat carotid body. Similar results were obtained in the carotid body and glomus cells from CaV3.2 knockout (Cacna1h−/−) mice. Since cystathionine-γ-lyase (CSE)-derived H2S is a critical mediator of the carotid body response to hypoxia, the role of T-type VGCCs in H2S-mediated O2 sensing was examined. Like hypoxia, NaHS, a H2S donor, increased intracellular Ca2+ concentration and augmented carotid body sensory nerve activity in wild-type mice, and these effects were markedly attenuated in Cacna1h−/− mice. In wild-type mice, TTA-A2 markedly attenuated glomus cell and carotid body sensory nerve responses to hypoxia, and these effects were absent in CSE knockout mice. These results demonstrate that CaV3.2 T-type VGCCs contribute to the H2S-mediated carotid body response to hypoxia.

Keywords: O2 sensing, voltage-gated calcium channels, T-type calcium channel, carotid body, mibefradil

voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCCs) are critical for Ca2+ influx and neurotransmission in the nervous system (2, 13). On the basis of their activation properties, VGCCs are divided into high- and low-voltage-activated channels. High-threshold VGCCs are further subdivided into L, N, P/Q, and R types, while low-voltage-activated Ca2+ channels are represented by T-type VGCCs (3, 6), designated CaV3.1, CaV3.2, and CaV3.3 channels, which contain pore-forming α1G-, α1H-, and α1I-subunits, respectively (3, 29).

Carotid bodies are the sensory organs for monitoring arterial blood O2 levels. Hypoxemia (i.e., reduced O2 levels in blood) increases carotid body sensory nerve activity and triggers the chemosensory reflex, which is critical for maintaining cardiorespiratory functions during low O2 (10). The carotid body consists of two cell types: 1) glomus (also called type I) cells, the primary O2-sensing cells, and 2) type II cells (10). Sensory nerve excitation by hypoxia requires elevation of intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) (1, 14, 30) and release of Ca2+-dependent neurotransmitter(s) from glomus cells (16, 30).

Previous studies have shown that VGCCs are critical for elevation of hypoxia-evoked [Ca2+]i in glomus cells (10). Glomus cells express high-voltage-activated Ca2+ currents, including L-, N-, and P-type currents, as well as “blocker-resistant” Ca2+ currents (7, 18, 31), and L-type VGCCs mediate a substantial portion of the hypoxia-induced Ca2+ influx (1, 26). Relatively little information is available on the role of the T-type VGCC in the carotid body. A nickel-sensitive Ca2+ current was reported in rat glomus cells (7). Since nickel is known to block T-type VGCCs (11), this finding suggests that glomus cells also express T-type VGCCs. The rat carotid body expresses mRNA encoding the α1G-subunit, and the CaV3.1 channel was proposed to contribute to hypoxia-evoked catecholamine (CA) efflux (5). However, the roles of the other T-type VGCC isoforms in the carotid body response to hypoxia have not been examined.

Recent studies have shown that dorsal root ganglion cells express T-type VGCCs and that their activation by H2S contributes to hyperalgesia (17). Cystathionine-γ-lyase (CSE)-generated H2S is required for VGCC-mediated [Ca2+]i influx in glomus cells (14) and sensory nerve excitation of the carotid body (12, 20). Whether H2S is required for the T-type VGCC-dependent carotid body response to hypoxia, however, is not known.

In the present study we determined the expression and localization of T-type VGCCs in the carotid body, assessed their functional significance using pharmacological and genetic approaches, and elucidated the role of H2S. Our results demonstrate that the CaV3.2 channel is the predominant T-type VGCC expressed in glomus cells and contributes to hypoxia-evoked Ca2+ influx and CA secretion, as well as sensory nerve excitation. Our results further demonstrate that CSE-derived H2S is required for the CaV3.2 channel-dependent carotid body response to hypoxia.

METHODS

Experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of The University of Chicago. All experiments were performed on adult male Sprague-Dawley rats and age- and sex-matched CaV3.2 knockout (Cacna1h−/−), CSE null (CSE−/−), and C57BL/6J mice.

Real-time RT-PCR.

Carotid bodies were harvested from anesthetized rats (n = 4 rats). Two carotid bodies were pooled, and RNA was extracted using TRIzol and reverse-transcribed using SuperScript III reverse transcriptase. Real-time RT-PCR was performed using a MiniOpticon system (Bio-Rad Laboratories) with the SYBR GreenER two-step quantitative RT-PCR kit (catalog no. 11764-100, Invitrogen). Primer sequences for real-time RT-PCR amplification were as follows: GTAACCCGTTGAACCCCATT (forward) and CCATCCAATCGGTAGTAGCG (reverse) for 18S (151 aa; GenBank accession no. X_01117), 5′CTTTGACCTGCTGACACTCTG (forward) and GCCATTACAGTCTTGGTGCTCA (reverse) for CaV3.1 (185 aa; GenBank accession no. AF290212), ACTTGGCCATCGTCCTCCTA (forward) and ATGGTGGGATTGATGGGCAG (reverse) for CaV3.2 (101 aa; GenBank accession no. AF290213), and GACCCCAGAGCAGTGAGGAT (forward) and TACTTGCTGTCCACGATGCC (reverse) for CaV3.3 (155 aa; GenBank accession no. AF 290214). Relative mRNA quantification was calculated using the comparative threshold (CT) method according to the following formula: 2−ΔCT, where ΔCT is the difference between the threshold cycle of the given target cDNA. The CT value was taken as a fractional cycle number at which the emitted fluorescence of the sample passes a fixed threshold above the baseline. mRNA levels were normalized to the 18S gene. For confirmation of the purity and specificity of all products, the template was omitted and a standard melting curve analysis was performed.

Immunocytochemistry.

Urethane (1.2 g/kg ip)-anesthetized rats (n = 4) were perfused transcardially with heparinized saline followed by 4% (vol/vol) paraformaldehyde. The carotid bifurcations were dissected and immersed in 25% sucrose solution in distilled water at 4°C for 16–24 h. The tissues were mounted in OCT compound, and 8- to 10-μm-thick sagittal sections were cut and processed for immunofluorescence. The tissue sections were treated with 20% normal goat serum and 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 2 h and then incubated with polyclonal anti-α1H (1:200 dilution; catalog no. ACC-025, Alomone Labs) and monoclonal anti-tyrosine hydroxylase (TH, 1:2,000 dilution; Sigma) antibodies in PBS with 1% normal goat serum and 0.2% Triton X-100. Control sections were treated with primary anti-α1H antibody preincubated with α1H control peptide (1:200 dilution; Alomone Labs). Immunostained regions were visualized with secondary antibodies fluorescently labeled with Alexa Red and Alexa Green (Molecular Probes). Sections mounted in Vectashield containing DAPI (Vector Labs) were analyzed using a fluorescence microscope (Eclipse E600, Nikon).

Western blot assay.

Dorsal root ganglia were harvested from urethane (1.2 g/kg ip)-anesthetized rats and homogenized in buffer containing 25 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.6, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, PMSF, and protease inhibitor cocktail. Tissue extracts containing equal amounts of proteins (1 mg/ml) were separated on a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred to a polyvinylpyrrolidone difluoride membrane. Membranes were probed with primary polyclonal anti-α1H antibody (1:200 dilution; catalog no. ACC-025, Alomone Labs). Control membrane was probed with anti-α1H antibody preincubated with equimolar α1H control peptide (1:200 dilution) as described above. The immune complexes were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (Amersham).

Carotid body sensory activity.

The protocol for recording sensory activity from ex vivo carotid bodies was essentially the same as that described previously (21). Briefly, the carotid body with the sinus nerve was placed in a recording chamber (250-μl volume) and superfused at a rate of 2.5 ml/min with warm (36°C) physiological saline (in mM: 125 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 2 MgSO4, 1.2 NaH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, 10 d-glucose, and 5 sucrose). The medium was bubbled with 21% O2-5% CO2. Po2 (141 ± 2.8 mmHg), Pco2 (35 ± 3 mmHg), and pH (7.36 ± 0.01) were determined by a blood gas analyzer (model ABL 5, Radiometer, Copenhagen, Denmark). To facilitate recording of clearly identifiable action potentials, the sinus nerve was treated with 0.1% collagenase for 5 min. Action potentials (2–4 active units) were recorded from one of the nerve bundles with a suction electrode, amplified (AC preamplifier, 100–3,000 Hz bandwidth; model P511K, Grass Instrument), displayed on an oscilloscope (model 5B12N, Tektronix), and stored in a computer via an analog-to-digital translation board (PowerLab/8P, ADInstruments). “Single” units were selected on the basis of the height and duration of the individual action potentials using a spike discrimination program (Spike Histogram Program, PowerLab, ADInstruments).

Primary cultures of glomus cells.

Primary cultures of glomus cells were prepared essentially as described elsewhere (14, 19). Briefly, carotid bodies were harvested from urethane (1.2 g/kg ip)-anesthetized rats and mice, and glomus cells were dissociated using a mixture of collagenase P (2 mg/ml; Roche), DNase (15 μg/ml; Sigma), and bovine serum albumin (3 mg/ml; Sigma) at 37°C for 20 min and then incubated for 15 min in medium containing DNase (30 μg/ml). Cells were plated on collagen (type VII; Sigma)-coated coverslips and maintained at 37°C in a 7% CO2-20% O2 incubator for 24 h. The growth medium consisted of F-12K medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 1% fetal bovine serum, insulin-transferrin-selenium (ITS-X, Invitrogen), and 1% penicillin-streptomycin-glutamine (Invitrogen).

Measurement of [Ca2+]i.

Glomus cells were incubated in Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS) with 2 μM fura 2-AM and 1 mg/ml albumin for 30 min and then washed in a fura 2-free solution for 30 min at 37°C. The coverslip was transferred to an experimental chamber for determination of changes in [Ca2+]i. Background fluorescence at 340- and 380-nm wavelengths was obtained from an area of the coverslip that was devoid of cells. On each coverslip, 5–12 glomus cells were selected (identified by their characteristic clustering) and individual cells were imaged. Image pairs (one at 340 nm and the other at 380 nm) were obtained every 2 s by averaging 16 frames at each wavelength. Data were continuously collected throughout the experiment. Background fluorescence was subtracted from the individual wavelengths. The image obtained at 340 nm was divided by the image at 380 nm to obtain the ratiometric image. Ratios were converted to free [Ca2+]i using calibration curves constructed in vitro by addition of fura 2 (50 μM free acid) to solutions containing known concentrations of Ca2+ (0–2,000 nM). The recording chamber was continually superfused with solution from gravity-fed reservoirs.

Measurement of CA secretion.

CA secretion from glomus cells was monitored by amperometry as described previously (14, 19). Briefly, recordings were made from adherent cells that were under constant perfusion with a flow rate of ∼1.0 ml/min (∼80-μl chamber volume). The electrode was held at +700 mV vs. a ground electrode using an NPI VA-10 amplifier to oxidize CAs. The amperometric signal was low-pass-filtered at 2 kHz (8-pole Bessel; Warner Instruments) and sampled into a computer at 10 kHz using a 16-bit analog-to-digital converter (National Instruments). Records with root-mean-square noise >1.0 pA were not analyzed. Amperometric spike features, quantal size, and kinetic parameters were analyzed using a series of macros written in Igor Pro (WaveMetrics). The number of secretory events and the amount of CA secreted per event were analyzed in each experiment, and data are presented as total CAs secreted. All experiments were performed at ambient temperature (23 ± 2°C), and the solutions consisted of (in mM) 137.93 NaCl, 1.26 CaCl2, 0.4 MgCl2·6H2O, 0.49 MgSO4·7H2O, 5.33 KCl, 0.44 KH2PO4, 0.34 Na2HPO4·7H2O, 5.56 dextrose, and 20 HEPES at pH 7.35 with an osmolarity of 300 mosM. Control normoxic solutions were equilibrated with room air (Po2 ∼146 mmHg). For hypoxia challenge, solutions were degassed and equilibrated with 1% O2 balanced with 99% N2, which resulted in final medium Po2 of ∼30 mmHg as measured by a blood gas analyzer.

Drugs and chemicals.

All stock solutions were made fresh before the experiments. Mibefradil (Sigma-Aldrich), nifedipine (Sigma-Aldrich), TTA-A2 ([2-(4-cyclopropylphenyl)-N-((1R)-1-[5-[(2,2,2-trifluoroethyl)oxo]-pyridin-2-yl]ethyl)acetamide]; Alomone Labs), and NaHS (Sigma-Aldrich) were obtained from commercial sources. Mibefradil and nifedipine stock solutions were made in HBSS. TTA-A2 stock solution was made in DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich; 0.002% final concentration of DMSO), and the pH of final solution was adjusted to ∼7.4. Stock solutions of NaHS (30 mM) were prepared in HBSS, with pH adjusted to ∼7.4, and were kept on ice. Desired concentrations were added to glomus cell culture plates or to the reservoirs containing medium irrigating the ex vivo carotid body preparation.

Analysis of data.

Average data are presented as means ± SE. Statistical significance was assessed by Student's t-test for statistical comparisons between two groups and one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's test for multiple-group comparisons. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

T-type VGCC expression in the carotid body.

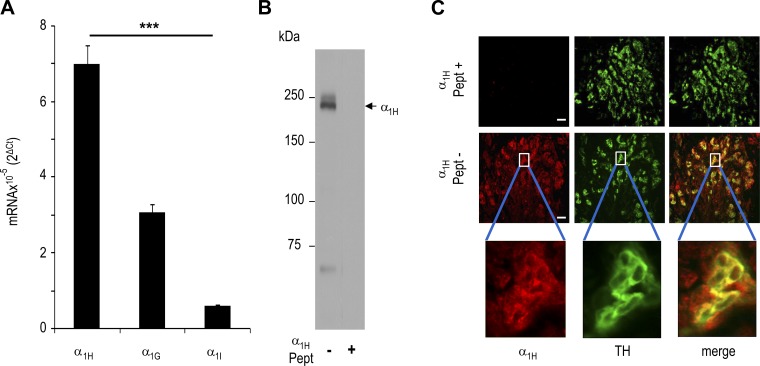

We first determined the expression of mRNAs encoding α1H-, α1G-, and α1I-subunits of T-type VGCC isoforms in the rat carotid bodies by real-time quantitative PCR. Rat carotid body expressed mRNAs encoding α1H- α1G-, and α1I-subunits, and α1H mRNA was more abundant than α1G and α1I mRNA (P < 0.001; Fig. 1A). Localization of α1H protein was determined by immunocytochemistry. Specificity of the anti-α1H antibody was determined by Western blot assay of the rat dorsal root ganglion, which expresses α1H (28). Immunoblot assay showed a single discrete protein band with a molecular weight corresponding to that of α1H, and this protein was absent following preincubation of the antibody with the control α1H peptide (Fig. 1B). Carotid body sections were stained with anti-α1H and -TH antibodies, the latter of which served as a marker of glomus cells (32). α1H-like immunoreactivity was seen predominantly in glomus cells, as evidenced by its colocalization with TH-positive cells (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

T-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channel (VGCC) expression in rat carotid body. A: real-time RT-PCR analysis of mRNAs encoding α1H-, α1G-, and α1I-subunits of T-type VGCCs in rat carotid bodies. Data were normalized to 18S mRNA and are expressed as fold change. Values are means ± SE from 4 individual experiments performed in triplicate. ***P < 0.001 vs. α1H. B: immunoblots of rat dorsal root ganglion with anti-α1H antibodies with (right) and without (left) α1H control peptide (Pept). Arrow points to a protein band corresponding to molecular weight of α1H. C: α1H protein expression in rat carotid body glomus cells. Carotid bodies were stained with antibodies specific for α1H (red) or tyrosine hydroxylase (TH, green), a marker of glomus cells. Individual staining and merged images are shown. Top and middle: immunostaining with and without α1H control peptide (Pept+ and Pept−, respectively). Bottom: enlarged (×8) images of glomus cells enclosed in white rectangles. Scale bars = 100 μm.

T-type VGCCs contribute to hypoxia-evoked Ca2+ influx in glomus cells.

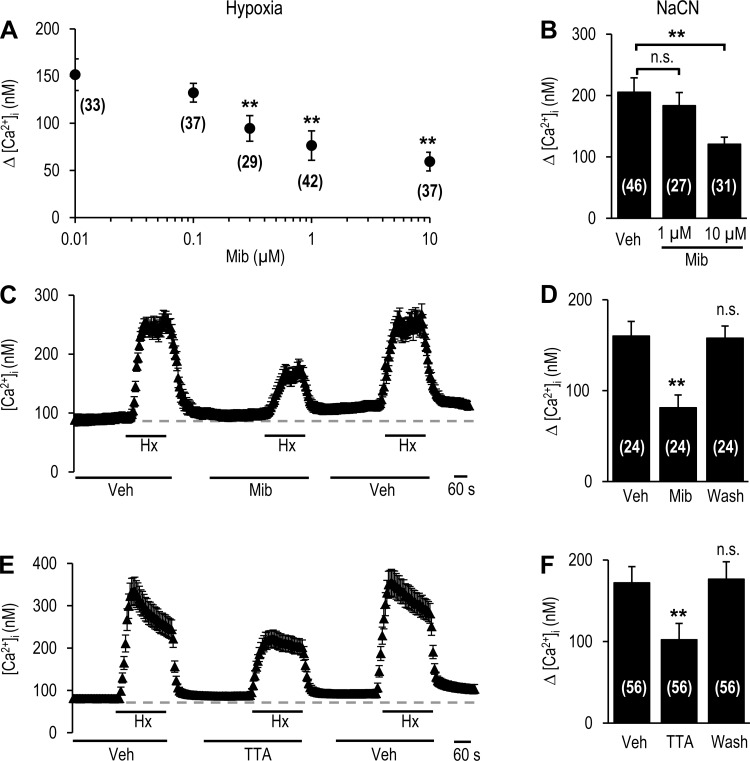

Hypoxia increases Ca2+ influx in glomus cells (10). The role of T-type VGCCs in hypoxia (Po2 ∼30 mmHg)-induced Ca2+ influx was determined in rat glomus cells. Changes in [Ca2+]i were monitored in the presence of increasing concentrations of mibefradil, a pan T-type VGCC blocker (15, 23). Hypoxia increased [Ca2+]i, and this effect was reduced by mibefradil in a dose-dependent manner, with a maximum response at 1 μM (49 ± 14% reduction, P < 0.01; Fig. 2A). However, sodium cyanide (NaCN, 3 μM)-induced Ca2+ influx was unaffected by 1 μM mibefradil (Fig. 2B). Increasing mibefradil concentration to 10 μM not only inhibited hypoxia, but also NaCN-evoked Ca2+ influx (Fig. 2, A and B), suggesting that >1 μM mibefradil exerts nonselective action. Consequently, further studies were performed with 1 μM mibefradil, which selectively affected hypoxia-evoked Ca2+ influx.

Fig. 2.

T-type VGCC blockers attenuate hypoxia-induced elevation of intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) in glomus cells of rat carotid body. A: [Ca2+]i response of glomus cells treated with 0.01–10 μM mibefradil (Mib), a blocker of T-type VGCCs, to hypoxia (Po2 ∼30 mmHg). Changes in [Ca2+]i (Δ[Ca2+]i) reflect response to hypoxia minus baseline levels. Values are means ± SE of number of cells shown in parentheses. **P < 0.01 vs. untreated controls. B: [Ca2+]i response to 3 μM NaCN. Δ[Ca2+]i represents response to NaCN minus baseline levels in the presence of vehicle (Veh) or mibefradil. Values are means ± SE of number of cells shown in parentheses. **P < 0.01 vs. Veh; ns, not significantly different (P > 0.05). C and E: representative examples of [Ca2+]i response of glomus cells to hypoxia (Hx; Po2 ∼30 mmHg) in the presence of vehicle or 1 μM mibefradil (C) or 25 μM TTA-A2 (TTA, E). Horizontal bars show duration of challenges with hypoxia or vehicle, mibefradil, or TTA-A2. D and F: [Ca2+]i response to hypoxia presented as Δ[Ca2+]i, i.e., response to hypoxia minus baseline levels in the presence of vehicle or 1 μM mibefradil (D) or 25 μM TTA-A2 (F). Wash, 5 min after washout of mibefradil or TTA-A2. Values are means ± SE of number of cells shown in parentheses. **P < 0.01 vs. Veh.

The effects of 1 μM mibefradil were completely reversed within 5 min after washout of the drug (Fig. 2, C and D). The residual hypoxia-induced [Ca2+]i elevation following mibefradil was blocked by 80 ± 11% (P < 0.01) in the presence of 5 μM nifedipine, an L-type VGCC blocker. To further establish the role of T-type VGCCs, we examined the effects of TTA-A2, another selective T-type VGCC blocker (8, 9, 24). On the basis of preliminary studies, we tested the effects of 25 μM TTA-A2. As shown in Fig. 2, E and F, TTA-A2 reversibly attenuated [Ca2+]i responses to hypoxia (41 ± 16% reduction, P < 0.01).

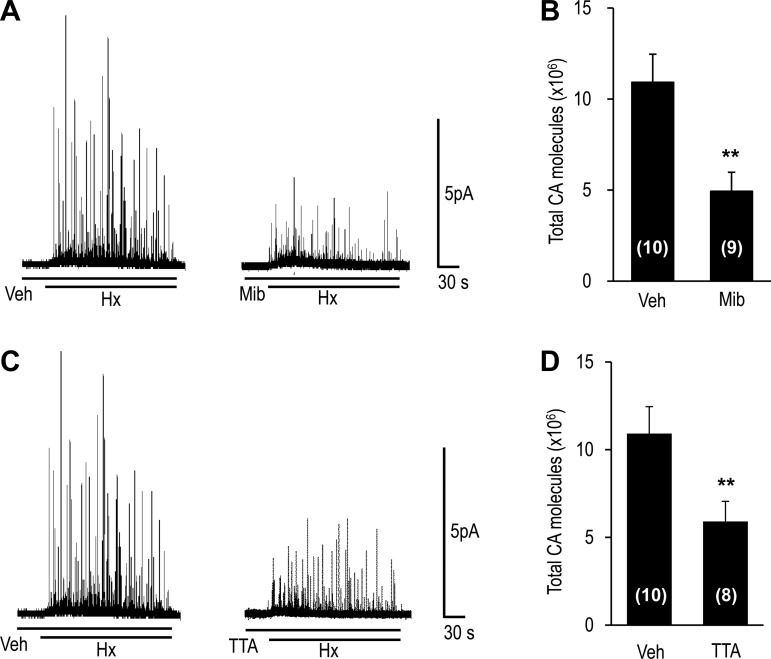

T-type VGCCs contribute to hypoxia-evoked CA secretion and carotid body sensory nerve activity.

Hypoxia releases CAs from glomus cells in a Ca2+-dependent manner (10). CA secretion from individual glomus cells was monitored by amperometry in the presence of either 1 μM mibefradil or 25 μM TTA-A2. Hypoxia-evoked CA secretion was markedly reduced in the presence of mibefradil or TTA-A2 (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Effect of T-type VGCC blockers on hypoxia-evoked catecholamine (CA) secretion from glomus cells. Glomus cells were isolated from carotid bodies harvested from anesthetized rats, and CA secretion was monitored by amperometry. A and C: hypoxia (Po2 ∼30 mmHg)-evoked CA secretion from rat glomus cells in the presence of vehicle or 1 μM mibefradil or 25 μM TTA-A2. Horizontal bars show duration of challenges with hypoxia or vehicle, mibefradil, or TTA-A2. B and D: total number of CA molecules secreted during hypoxia. Values are means ± SE of number of cells shown in parentheses. **P < 0.01 vs. Veh.

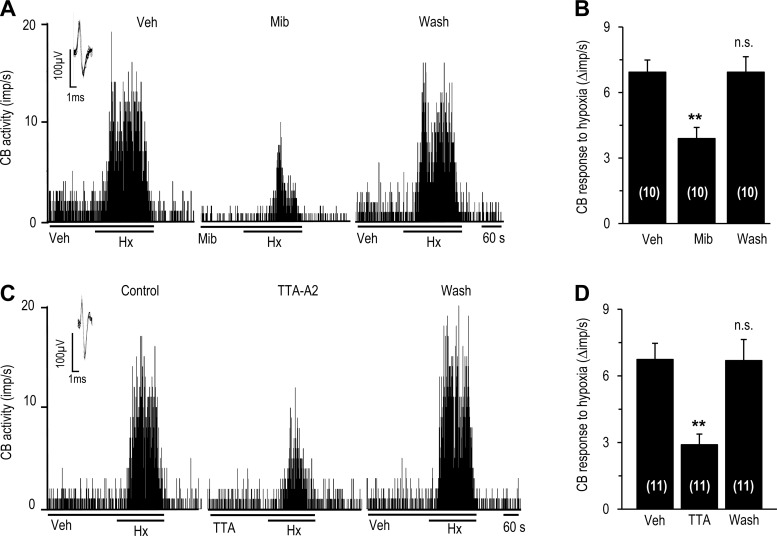

We then tested the effects of T-type VGCC blockers on the carotid body sensory nerve response to hypoxia. These experiments utilized an ex vivo carotid body preparation to exclude the confounding influence of T-type VGCC blockers on blood pressure in intact rats. Hypoxia resulted in an increase in sensory nerve activity, which was markedly attenuated in the presence of mibefradil (1 μM) or TTA-A2 (25 μM) in a reversible manner (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Effect of T-type Ca2+ channel blockers on carotid body sensory response to hypoxia. Carotid bodies were harvested from anesthetized rats, and sensory nerve activity was recorded ex vivo. A and C: representative examples of sensory nerve responses [impulses (imp)/s] to hypoxia (Po2 ∼30 mmHg) in the presence of vehicle or 1 μM mibefradil (A) or 25 μM TTA-A2 (C) and 5 min after washout of drugs. Horizontal bars show duration of challenges. Inset: superimposed action potentials of a “single” fiber from which data were derived. B and D: effects of 1 μM mibefradil or TTA-A2 on sensory nerve response to hypoxia. Data are presented as change (Δimp/s), i.e., stimulus-evoked activity minus baseline activity. Values are means ± SE of number of experiments shown in parentheses. **P < 0.01 vs. Veh.

Selective contribution of CaV3.2 to the glomus cell and carotid body response to hypoxia.

Since glomus cells express α1H, the pore-forming subunit of the CaV3.2 subtype of T-type VGCC (Fig. 1), we sought to determine the selective role of CaV3.2 in the carotid body response to hypoxia. Studies were performed on mice with homozygous deletion of the α1H allele (Cacna1h−/−), which exhibit attenuated CaV3.2 T-type Ca2+ current (4).

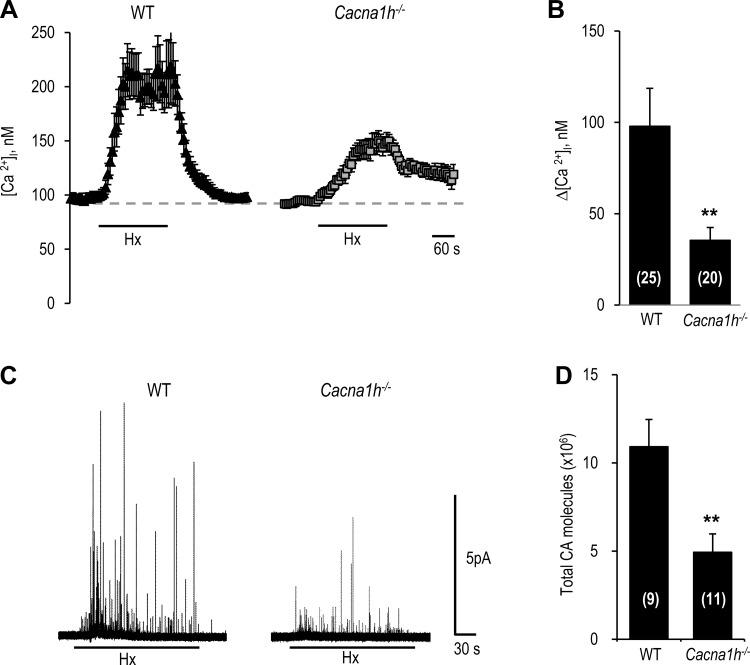

Hypoxia-evoked [Ca2+]i elevation and CA secretion were significantly reduced in glomus cells from Cacna1h−/− mice compared with wild-type (WT) controls (Fig. 5). On average, [Ca2+]i and CA secretory responses were attenuated by 63 ± 14.6% and 55 ± 4.0%, respectively, in cells from Cacna1h−/− mice (P < 0.01; Fig. 5, B and D). Similarly, carotid bodies from Cacna1h−/− mice exhibited a markedly attenuated sensory nerve response to hypoxia compared with WT controls (P < 0.01; Fig. 6, A and B). However, NaCN-evoked sensory nerve excitation was comparable in carotid bodies from Cacna1h−/− and WT mice (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 5.

Glomus cell [Ca2+]i and CA secretory responses to hypoxia in wild-type (WT) and CaV3.2 knockout (Cacna1h−/−) mice. A: representative examples of [Ca2+]i responses of glomus cells from WT and Cacna1h−/− mice to hypoxia (Po2 ∼30 mmHg). B: [Ca2+]i responses to hypoxia, presented as change (Δ), i.e., stimulus-evoked response minus baseline levels. Values are means ± SE of number of cells shown in parentheses. C: representative examples of hypoxia (Po2 ∼30 mmHg)-evoked CA secretion from glomus cells from WT and Cacna1h−/− mice. Horizontal bars in A and C show duration of hypoxic challenge. D: total number of CA molecules secreted during hypoxia. Values are means ± SE of number of cells shown in parentheses. **P < 0.01 vs. WT.

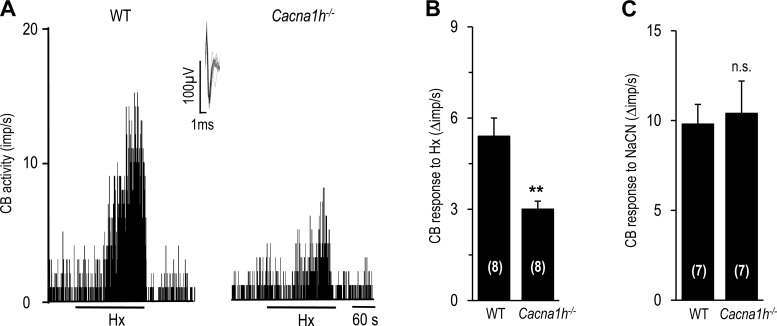

Fig. 6.

Carotid body (CB) sensory response to hypoxia in WT and Cacna1h−/− mice. A: representative examples of carotid body sensory nerve responses to hypoxia (Po2 ∼30 mmHg) in WT and Cacna1h−/− mice. Horizontal bars show duration of hypoxic challenge. Inset: superimposed action potentials of a “single” fiber from which data were derived. B and C: carotid body sensory nerve response to hypoxia (B) or 3 μM NaCN (C) presented as change (Δ), i.e., stimulus-evoked activity minus baseline activity. Values are means ± SE of number of experiments shown in parentheses. **P < 0.01 vs. WT.

H2S is required for the CaV3.2-dependent carotid body response to hypoxia.

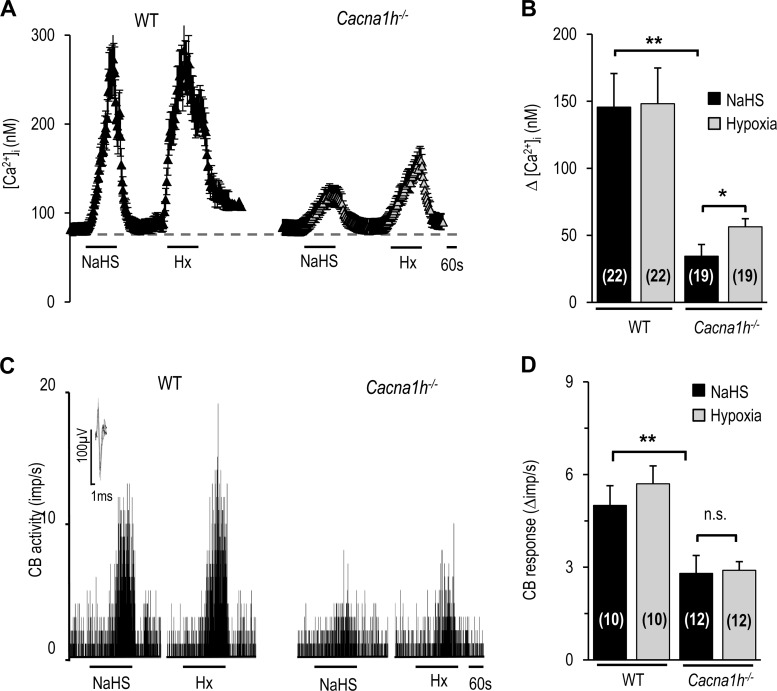

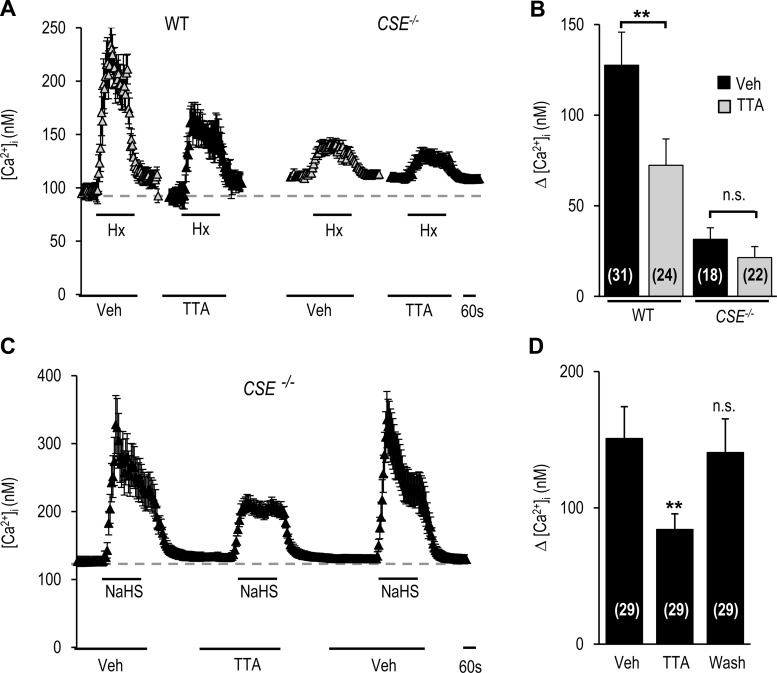

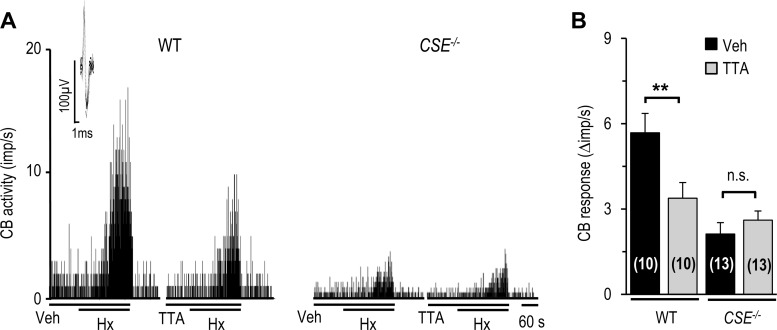

Recent studies reported that CSE-derived H2S is a critical mediator of the carotid body response to hypoxia (12, 14, 20, 27). We hypothesized that the CaV3.2-dependent carotid body response to hypoxia requires H2S. This possibility was tested in WT and Cacna1h−/− mice. In WT mice, NaHS, a H2S donor, like hypoxia, increased [Ca2+]i in glomus cells and carotid body sensory nerve activity, and these responses were markedly reduced in glomus cells and carotid bodies from Cacna1h−/− mice (Fig. 7). To assess the selective role of CSE-derived H2S, studies were performed on WT and CSE−/− mice. Hypoxia increased [Ca2+]i in glomus cells, and this response was attenuated by TTA-A2 in glomus cells from WT, but not CSE−/−, mice (Fig. 8, A and B). To determine whether genetic deletion of CSE impaired T-type VGCC function, glomus cells from CSE−/− mice were challenged with NaHS. In response to NaHS, [Ca2+]i increased, and this effect was inhibited by TTA-A2 in a reversible manner (Fig. 8, C and D). Hypoxia-evoked carotid body sensory nerve excitation was reduced by TTA-A2 in carotid bodies from WT, but not CSE−/−, mice (Fig. 9).

Fig. 7.

Glomus cell and carotid body responses to NaHS in WT and Cacna1h−/− mice. A: representative examples of [Ca2+]i responses to 50 μM NaHS and hypoxia (Po2 ∼30 mmHg) in glomus cells from WT and Cacna1h−/− mice. B: [Ca2+]i responses to 50 μM NaHS and hypoxia in glomus cells from WT and Cacna1h−/− mice, analyzed as change (Δ), i.e., stimulus-evoked response minus baseline levels. Values are means ± SE of number of cells shown in parentheses. C: representative examples of carotid body sensory nerve responses to 50 μM NaHS and hypoxia (Po2 ∼30 mmHg) in WT and Cacna1h−/− mice. Horizontal bars in A and C show duration of exposure to NaHS or hypoxia. D: carotid body sensory nerve response to NaHS or hypoxia, analyzed as change (Δ), i.e., stimulus-evoked activity minus baseline activity. Values are means ± SE of number of cells shown in parentheses. **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05 vs. WT.

Fig. 8.

Effect of TTA-A2 on [Ca2+]i responses of glomus cells from WT and cystathionine-γ-lyase (CSE) null (CSE−/−) mice to hypoxia and H2S. A and C: representative examples of [Ca2+]i responses to hypoxia (A) or 50 μM NaHS (C) in the presence of vehicle or 25 μM TTA-A2 in glomus cells from WT and CSE−/− mice. Horizontal bars show duration of exposure to NaHS, hypoxia, vehicle, and TTA-A2. B and D: [Ca2+]i responses of glomus cells from WT and CSE−/− mice to hypoxia (B) or 50 μM NaHS (D), presented as change (Δ), i.e., stimulus-evoked response minus baseline levels. Values are means ± SE of number of cells shown in parentheses. **P < 0.01 vs. Veh.

Fig. 9.

Effect of TTA-A2 on carotid body sensory nerve responses to hypoxia in WT and CSE−/− mice. A: representative examples of sensory nerve responses to hypoxia (Po2 ∼30 mmHg) in WT and CSE−/− mice in the presence of vehicle or TTA-A2. Horizontal bars show duration of hypoxia challenge, vehicle, or TTA-A2. Inset: superimposed action potentials of a “single” fiber from which data were derived. B: carotid body sensory response to hypoxia analyzed as change (Δ), i.e., stimulus-evoked activity minus baseline activity. Values are means ± SE of number of experiments shown in parentheses. **P < 0.01 vs. Veh.

DISCUSSION

The results of the present study demonstrate that carotid bodies express T-type VGCCs and establish their functional significance in O2 sensing. We found a higher abundance of α1H mRNA in carotid bodies from Sprague-Dawley rats as opposed to relatively high levels of α1G mRNA expression in Wistar rat carotid bodies as reported previously (5). Our data further demonstrate that much of the α1H protein is localized to glomus cells, the primary O2-sensing cells in the carotid body. The following findings demonstrate the functional significance of T-type VGCCs in carotid body O2 sensing. 1) Mibefradil and TTA-A2, the two established blockers of T-type VGCCs (15, 23, 24), effectively reduced hypoxia-induced Ca2+ influx in glomus cells by ∼50%, and these effects were reversible and selective to hypoxia, because Ca2+ influx by NaCN was unaffected. 2) T-type VGCC blockers were equally effective in reducing hypoxia-evoked CA secretion from glomus cells, as well as carotid body sensory nerve excitation. Previous studies reported that L-type VGCCs are the major contributors to Ca2+ influx by hypoxia in glomus cells (1, 14). Consistent with this possibility, we found that nifedipine, an L-type VGCC blocker, abolished ∼80% of the residual hypoxia-evoked Ca2+ influx following mibefradil. Together, these observations demonstrate that hypoxia-induced voltage-gated Ca2+ influx in glomus cells requires high-threshold (L-type) and low-threshold (T-type) VGCCs.

Mice with genetic absence of α1H (Cacna1h−/−) exhibited markedly attenuated glomus cell responses to hypoxia as well as carotid body sensory nerve excitation by hypoxia, whereas carotid body responses to NaCN were unaltered in Cacna1h−/− mice. Furthermore, α1H is predominantly expressed in glomus cells. Since α1H constitutes the pore-forming subunit of CaV3.2, these observations demonstrate that CaV3.2 is the major T-type VGCC that contributes to hypoxia-evoked voltage-gated Ca2+ influx, neurotransmitter secretion, and carotid body sensory nerve excitation.

The following observations suggest that CSE-derived H2S is required for CaV3.2-dependent carotid body responses to hypoxia. 1) Like hypoxia, NaHS, a H2S donor, increased Ca2+ influx in glomus cells and carotid body sensory nerve activity, and these effects were absent in Cacna1h−/− mice. 2) The inhibitory effects of TTA-A2 on glomus cell and carotid body sensory nerve responses were strikingly absent in CSE−/− mice. The lack of TTA-A2 effect in CSE−/− mice is unlikely due to compromised CaV3.2 function, because a H2S donor still increased Ca2+ influx, which could be attenuated by TTA-A2. We previously reported that L-type VGCCs contribute in part to the H2S-mediated hypoxic sensing by the carotid body (14). The current findings suggest that, in addition to L-type VGCCs, H2S-dependent hypoxia sensing also requires CaV3.2, analogous to their proposed role in nociception (17). However, the effects of CSE-derived H2S on glomus cell CaV3.2 currents remain to be studied.

In summary, the present study employing pharmacological and genetic approaches establishes a role for T-type VGCCs, especially CaV3.2, in the carotid body sensory response to acute hypoxia. The carotid body response to hypoxia is augmented by chronic intermittent hypoxia (CIH), mimicking the O2 saturation profiles encountered with recurrent apnea (22). Given that CIH upregulates CaV3.2 in adrenal medullary chromaffin cells (25), it would be of interest to examine in future studies whether T-type VGCCs contribute to CIH-evoked heightened hypoxic sensitivity of the carotid body.

GRANTS

This research was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant HL-90554.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

V.V.M. and N.R.P. are responsible for conception and design of the research; V.V.M., Y.-J.P., G.Y., and J.N. performed the experiments; V.V.M., Y.-J.P., G.Y., and J.N. analyzed the data; V.V.M. and A.P.F. interpreted the results of the experiments; V.V.M., Y.-J.P., and J.N. prepared the figures; V.V.M. and N.R.P. drafted the manuscript; A.P.F., G.K.K., and N.R.P. edited and revised the manuscript; N.R.P. approved the final version of the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Prof. Solomon H. Snyder and Moataz M. Gadalla (Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine) for providing CSE−/− mice.

REFERENCES

- 1.Buckler KJ, Vaughan-Jones RD. Effects of hypoxia on membrane potential and intracellular calcium in rat neonatal carotid body type I cells. J Physiol 476: 423–428, 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Catterall WA. Voltage-gated calcium channels. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 3: a003947, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Catterall WA, Perez-Reyes E, Snutch TP, Striessnig J. International Union of Pharmacology. XLVIII. Nomenclature and structure-function relationships of voltage-gated calcium channels. Pharmacol Rev 57: 411–425, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen CC, Lamping KG, Nuno DW, Barresi R, Prouty SJ, Lavoie JL, Cribbs LL, England SK, Sigmund CD, Weiss RM, Williamson RA, Hill JA, Campbell KP. Abnormal coronary function in mice deficient in α1H T-type Ca2+ channels. Science 302: 1416–1418, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cáceres AI, Gonzalez-Obeso E, Gonzalez C, Rocher A. RT-PCR and pharmacological analysis of L- and T-type calcium channels in rat carotid body. Adv Exp Med Biol 648: 105–112, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dolphin AC. Calcium channel diversity: multiple roles of calcium channel subunits. Curr Opin Neurobiol 19: 237–244, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.e Silva MJ, Lewis DL. L- and N-type Ca2+ channels in adult rat carotid body chemoreceptor type I cells. J Physiol 489: 689–699, 1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Francois A, Kerckhove N, Meleine M, Alloui A, Barrere C, Gelot A, Uebele VN, Renger JJ, Eschalier A, Ardid D, Bourinet E. State-dependent properties of a new T-type calcium channel blocker enhance CaV3.2 selectivity and support analgesic effects. Pain 154: 283–293, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kraus RL, Li Y, Gregan Y, Gotter AL, Uebele VN, Fox SV, Doran SM, Barrow JC, Yang ZQ, Reger TS, Koblan KS, Renger JJ. In vitro characterization of T-type calcium channel antagonist TTA-A2 and in vivo effects on arousal in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 335: 409–417, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumar P, Prabhakar NR. Peripheral chemoreceptors: function and plasticity of the carotid body. Compr Physiol 2: 141–219, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee JH, Gomora JC, Cribbs LL, Perez-Reyes E. Nickel block of three cloned T-type calcium channels: low concentrations selectively block α1H. Biophys J 77: 3034–3042, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li Q, Sun BY, Wang XF, Jin Z, Zhou Y, Dong L, Jiang LH, Rong WF. A crucial role for hydrogen sulfide in oxygen sensing via modulating large conductance calcium-activated potassium channels. Antioxid Redox Signaling 12: 1179–1189, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lipscombe D, Allen SE, Toro CP. Control of neuronal voltage-gated calcium ion channels from RNA to protein. Trends Neurosci 36: 598–609, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Makarenko VV, Nanduri J, Raghuraman G, Fox AP, Gadalla MM, Kumar GK, Snyder SH, Prabhakar NR. Endogenous H2S is required for hypoxic sensing by carotid body glomus cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 303: C916–C923, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martin RL, Lee JH, Cribbs LL, Perez-Reyes E, Hanck DA. Mibefradil block of cloned T-type calcium channels. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 295: 302–308, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Obeso A, Rocher A, Fidone S, Gonzalez C. The role of dihydropyridine-sensitive Ca2+ channels in stimulus-evoked catecholamine release from chemoreceptor cells of the carotid body. Neuroscience 47: 463–472, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okubo K, Takahashi T, Sekiguchi F, Kanaoka D, Matsunami M, Ohkubo T, Yamazaki J, Fukushima N, Yoshida S, Kawabata A. Inhibition of T-type calcium channels and hydrogen sulfide-forming enzyme reverses paclitaxel-evoked neuropathic hyperalgesia in rats. Neuroscience 188: 148–156, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Overholt JL, Prabhakar NR. Ca2+ current in rabbit carotid body glomus cells is conducted by multiple types of high-voltage-activated Ca2+ channels. J Neurophysiol 78: 2467–2474, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peng YJ, Makarenko VV, Nanduri J, Vasavda C, Raghuraman G, Yuan G, Gadalla MM, Kumar GK, Snyder SH, Prabhakar NR. Inherent variations in CO-H2S-mediated carotid body O2 sensing mediate hypertension and pulmonary edema. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111: 1174–1179, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peng YJ, Nanduri J, Raghuraman G, Souvannakitti D, Gadalla MM, Kumar GK, Snyder SH, Prabhakar NR. H2S mediates O2 sensing in the carotid body. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 10719–10724, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peng YJ, Nanduri J, Yuan G, Wang N, Deneris E, Pendyala S, Natarajan V, Kumar GK, Prabhakar NR. NADPH oxidase is required for the sensory plasticity of the carotid body by chronic intermittent hypoxia. J Neurosci 29: 4903–4910, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prabhakar NR, Fields RD, Baker T, Fletcher EC. Intermittent hypoxia: cell to system. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 281: L524–L528, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Randall AD, Tsien RW. Contrasting biophysical and pharmacological properties of T-type and R-type calcium channels. Neuropharmacology 36: 879–893, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shipe WD, Barrow JC, Yang ZQ, Lindsley CW, Yang FV, Schlegel KA, Shu Y, Rittle KE, Bock MG, Hartman GD, Tang C, Ballard JE, Kuo Y, Adarayan ED, Prueksaritanont T, Zrada MM, Uebele VN, Nuss CE, Connolly TM, Doran SM, Fox SV, Kraus RL, Marino MJ, Graufelds VK, Vargas HM, Bunting PB, Hasbun-Manning M, Evans RM, Koblan KS, Renger JJ. Design, synthesis, and evaluation of a novel 4-aminomethyl-4-fluoropiperidine as a T-type Ca2+ channel antagonist. J Med Chem 51: 3692–3695, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Souvannakitti D, Nanduri J, Yuan G, Kumar GK, Fox AP, Prabhakar NR. NADPH oxidase-dependent regulation of T-type Ca2+ channels and ryanodine receptors mediate the augmented exocytosis of catecholamines from intermittent hypoxia-treated neonatal rat chromaffin cells. J Neurosci 30: 10763–10772, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Summers BA, Overholt JL, Prabhakar NR. Augmentation of L-type calcium current by hypoxia in rabbit carotid body glomus cells: evidence for a PKC-sensitive pathway. J Neurophysiol 84: 1636–1644, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Telezhkin V, Brazier SP, Cayzac S, Müller CT, Riccardi D, Kemp PJ. Hydrogen sulfide inhibits human BKCa channels. Adv Exp Med Biol 648: 65–72, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Todorovic SM, Jevtovic-Todorovic V. Neuropathic pain: role for presynaptic T-type channels in nociceptive signaling. Pflügers Arch 465: 921–927, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsien RW, Lipscombe D, Madison DV, Bley KR, Fox AP. Multiple types of neuronal calcium channels and their selective modulation. Trends Neurosci 11: 431–438, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ureña J, Fernández-Chacón R, Benot AR, Alvarez de Toledo GA, López-Barneo J. Hypoxia induces voltage-dependent Ca2+ entry and quantal dopamine secretion in carotid body glomus cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91: 10208–10211, 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ureña J, López-López J, González C, López-Barneo J. Ionic currents in dispersed chemoreceptor cells of the mammalian carotid body. J Gen Physiol 93: 979–999, 1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yuan G, Peng YJ, Reddy VD, Makarenko VV, Nanduri J, Khan SA, Garcia JA, Kumar GK, Semenza GL, Prabhakar NR. Mutual antagonism between hypoxia-inducible factors 1α and 2α regulates oxygen sensing and cardio-respiratory homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 1788–1796, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]