Abstract

The dysregulation of glucose-inhibited glucagon secretion from the pancreatic islet α-cell is a critical component of diabetes pathology and metabolic disease. We show a previously uncharacterized [Ca2+]i-independent mechanism of glucagon suppression in human and murine pancreatic islets whereby cAMP and PKA signaling are decreased. This decrease is driven by the combination of somatostatin, which inhibits adenylyl cyclase production of cAMP via the Gαi subunit of the SSTR2, and insulin, which acts via its receptor to activate phosphodiesterase 3B and degrade cytosolic cAMP. Our data indicate that both somatostatin and insulin signaling are required to suppress cAMP/PKA and glucagon secretion from both human and murine α-cells, and the combination of these two signaling mechanisms is sufficient to reduce glucagon secretion from isolated α-cells as well as islets. Thus, we conclude that somatostatin and insulin together are critical paracrine mediators of glucose-inhibited glucagon secretion and function by lowering cAMP/PKA signaling with increasing glucose.

Keywords: cyclic AMP, glucagon, pancreatic islets, insulin, somatostatin

glucagon plays a critical role in blood glucose homeostasis, and its secretion from pancreatic islet α-cells is inhibited with rising glucose. During diabetes, persistent glucagon secretion from α-cells leads to hyperglucagonemia, which overproduces glucose, exacerbating hyperglycemia. This makes the α-cell an important target for therapeutic intervention, but relatively little is known about how glucagon secretion is regulated under normal physiological conditions (18). There are many hypotheses about how glucagon is suppressed by glucose, including paracrine regulation by islet factors (28) and changes in ion channel activity (44), but they commonly depend on a decrease in intracellular Ca2+. However, published data show that glucagon inhibition is independent of intracellular Ca2+ activity, and no hypothesis explains the loss of suppression from purified α-cells (30, 31, 38). Progress toward understanding α-cell regulation and function has been hampered by a lack of approaches to measure α-cell properties without first separating them from the rest of the islet, which we know critically changes their function.

Multiple G protein-coupled somatostatin receptors (SSTRs) have been identified in islets. SSTR2 is the most abundantly expressed and functionally dominant isoform in both human and murine α-cells (12, 24). Upon SSTR2 activation by somatostatin, the Gαi subunit inhibits adenylyl cyclase to reduce cAMP. Isolated islets from SSTR2 knockout mice show a twofold increase in glucagon secretion, suggesting a role for somatostatin in glucose-inhibited glucagon secretion (37). In contrast, global somatostatin deletion does not lead to increased basal glucagon secretion (20), and infusion of a specific SSTR2 antagonist in the absence of insulin does not affect blood levels of glucagon or glucose (43). Although somatostatin is a potent inhibitor of islet hormone secretion, it is insufficient to suppress glucagon secretion from purified α-cells (30, 33). During diabetes, where insulin signaling is mostly dysfunctional, somatostatin is also insufficient to counter the observed chronic hyperglucagonemia, suggesting a role for insulin signaling (8, 21, 24, 37, 43).

Knockdown of the insulin receptor (IR) in isolated islets leads to changes in glucagon inhibition without any effect on insulin secretion, which points to a role of IR in α-cells (11). α-Cell-specific IR-knockout mice exhibit hyperglycemia, hyperglucagonemia, and glucose intolerance, although islet glucagon secretion has not been reported (26). It has been suggested that insulin reduces KATP channel sensitivity (16) or activates Akt downstream of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) to recruit GABA-A receptor to the membrane, which allows for inhibition by secreted GABA (42). However, GABA is insufficient to inhibit secretion in isolated α-cells, suggesting a more complicated mechanism (30, 31).

Another IR signaling pathway leads to activation of phosphodiesterase (PDE)3B, which degrades cellular cAMP and inhibits lipolysis in adipose tissue (45). Phosphodiesterase (PDE) inhibitors increase amino acid-stimulated glucagon secretion from isolated islets by increasing cAMP (23). Furthermore, the PDE inhibitors rolipram and cilostazol have shown efficacy in preventing diabetes in rodents (32) and diabetic complications in humans (25), respectively.

Secretion of both somatostatin and insulin is increased in response to glucose. Thus, we reasoned that these two hormones might work together to drive glucagon suppression. We hypothesize that α-cell cAMP is reduced upon glucose stimulation by somatostatin decreasing its production and insulin driving its degradation. To test this idea, we used secretion assays, [Ca2+]i imaging, and pharmacological manipulations along with semiquantitative immunofluorescence assays and a Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET)-based biosensor for cAMP in whole islets and purified α-cells. Together, the results build a self-consistent data set that points to a novel mechanism for glucagon suppression where the combined action of somatostatin and insulin lowers cAMP. Reduction of cAMP leads to decreased PKA phosphorylation, which correlates with decreased glucagon secretion.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Islet isolation and culture.

Animal studies were conducted in compliance with and approved by the Vanderbilt Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Pancreata from 8- to 15-wk-old C57BL/6 male mice expressing fluorescent protein [tandem-dimer red fluorescent protein (tdRFP)] in α-cells were isolated as described (31, 36) and cultured in RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) with 10% FBS (Invitrogen), penicillin-streptomycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and 11 mM glucose. Human islets were obtained from the Integrated Islet Distribution Program (IIDP) through Prof. David Jacobson (Vanderbilt University) and hand-picked into RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen) with 11 mM glucose and 2% BSA (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for 3–4 h of recovery before use.

Glucagon secretion assay.

Islets cultured overnight in media were incubated for 1 h in buffer consisting of 128.8 mM NaCl, 4.8 mM KCl, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 2.5 mM CaCl2, 20 mM HEPES, 5 mM NaHCO3 (pH 7.4), 0.1% BSA, and 2.8 mM glucose. Twelve to fifteen islets were transferred to buffer with 1 or 11 mM glucose with and without the following drugs (from Sigma, unless otherwise specified): 300 μM 8-bromoadenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (8-Br-cAMP), 300 μM 8-(4-chlorophenylthio)-2′-O-methyladenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate monosodium hydrate (8-O-Me-CPT), 300 μM N6-benzoyladenosine-3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate sodium salt (6-Bnz-cAMP), 100 nM or 1 μM insulin, 100 nM somatostatin, 1 μM S961 (Novo Nordisk, Princeton, NJ), 50 μM forskolin, 100 μM 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX), 100 μM Rp-cAMPS, 250 nM cyclosomatostatin (Tocris Bioscience, Minneapolis, MN), and/or 200 nM CYN154806 (Tocris Bioscience) for 45 min at 37°C before centrifugation and supernatant collection. 1.5% HCl-70% ethanol was added to the remaining pellet and vortexed for islet content quantification. Glucagon and insulin content and secretion were measured in duplicate with Glucagon ELISA (RayBiotech, Norcross, GA), Mouse UltraSensitive Insulin ELISA (Alpco, Salem, NH), or Human Insulin ELISA (Alpco). Studies with pertussis toxin used overnight islet pretreatment followed by secretion experiments.

Immunofluorescence.

Islets fixed in PBS containing 2% paraformaldehyde at 4°C were permeabilized overnight at 4°C in PBS with 0.3% Triton X-100, 5 mM sodium azide, 1% bovine serum albumin, and 5% goat serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME). Human islets were incubated with rabbit anti-glucagon (Abcam, Cambridge, MA), guinea pig anti-human insulin (EMD Millipore, Ballerica, MA), and mouse anti-cAMP (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) antibodies (all 1:250) for 24–48 h at 4°C, washed twice, incubated with secondary antibodies conjugated with AlexaFluor 488, 546, or 594 or Cy5 (all 1:1,000; Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) for 24 h, and washed twice before gelvotol mounting. Mouse islets were stained similarly, but with rabbit anti-insulin (Abcam), guinea pig anti-glucagon (EMD Millipore), mouse anti-cAMP (cat. no. ab24851; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), or rabbit anti-phospho-PKA antibodies (all 1:250; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA). The anti-CAMP antibody has previously been validated in mouse and human cells for immunofluorescence imaging and flow cytometry experiments (e.g., see Ref. 39). Immunofluorescence was detected by confocal microscopy using 488, 561, or 633 nm excitation and corresponding spectral windows (LSM780; Carl Zeiss, Thorwood, NY). Analysis was performed on raw data, but image lookup tables were compressed equally for gamma and brightness for presentation.

Live-cell imaging for calcium and cAMP.

Islets were incubated with 5 μM fluo 4-AM (Life Technologies) for 30 min at 2.8 mM glucose (31). After washing, islets equilibrated on the microscope stage for 15 min. Fluo 4 was excited at 488 nm and detected between 490 and 560 nm. α-Cells were identified by tdRFP excited by 561 nm. Confocal sections were obtained with an LSM710 or LSM780 (Carl Zeiss, Thorwood, NY), Fluar ×40/1.3 NA lens, and 2 Airy unit pinhole. Because β-cells constitute ∼80% of the cells in the islet (17), the signal from non-tdRFP cells in the islet center was considered to represent the average β-cell response. Mean intensities were normalized to five frames of data 8 min after reagent change. For purified α-cells after dispersion, cells were resuspended in PBS + 1 mM CaCl2 + 0.1% BSA at a cell density of 2 × 106̂ cell/ml. The cell suspension was mixed with 25 ug of the plasmid (mTurquoise2-epacQ270E-cpVenusVenus) in a 2-mm gap electroporation cuvette and electroporated with one square-wave pulse of 225 V for 5 ms using an ECM830 (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA). The cell suspension was transferred to Mattek dishes coated with poly-l-lysine and cultured overnight in the islet medium. Imaging was done in KRBH medium + 0.1% BSA. α-Cells were identified by their tdRFP fluorescence, and the cAMP biosensor was excited at 458 nm with, emissions collected using 465- to 508- and 517- to 561-nm bandpass filters.

Cell dispersion and FACS sorting.

Islets cultured overnight were washed in PBS at pH 7.4 without Ca2+ and MgCl2. Cells were dissociated with Accutase (Life Technologies) for 15 min at 37°C, pelleted, and resuspended in buffer with 11 mM glucose. One to two hours after dispersion, fluorescent α-cells were sorted using a BD FACSAria (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), yielding 100–800 viable α-cells per mouse.

Data analysis and statistics.

Data were analyzed with ImageJ, Fiji, MatLab, or GraphPad Prism software. For imaging data, mean fluorescence intensity was determined by region of interest after background subtraction. Data are reported as means ± SE, with P < 0.05 considered statistically significant as determined by Student's t-test.

RESULTS

Human and mouse islet α-cell cAMP response to glucose.

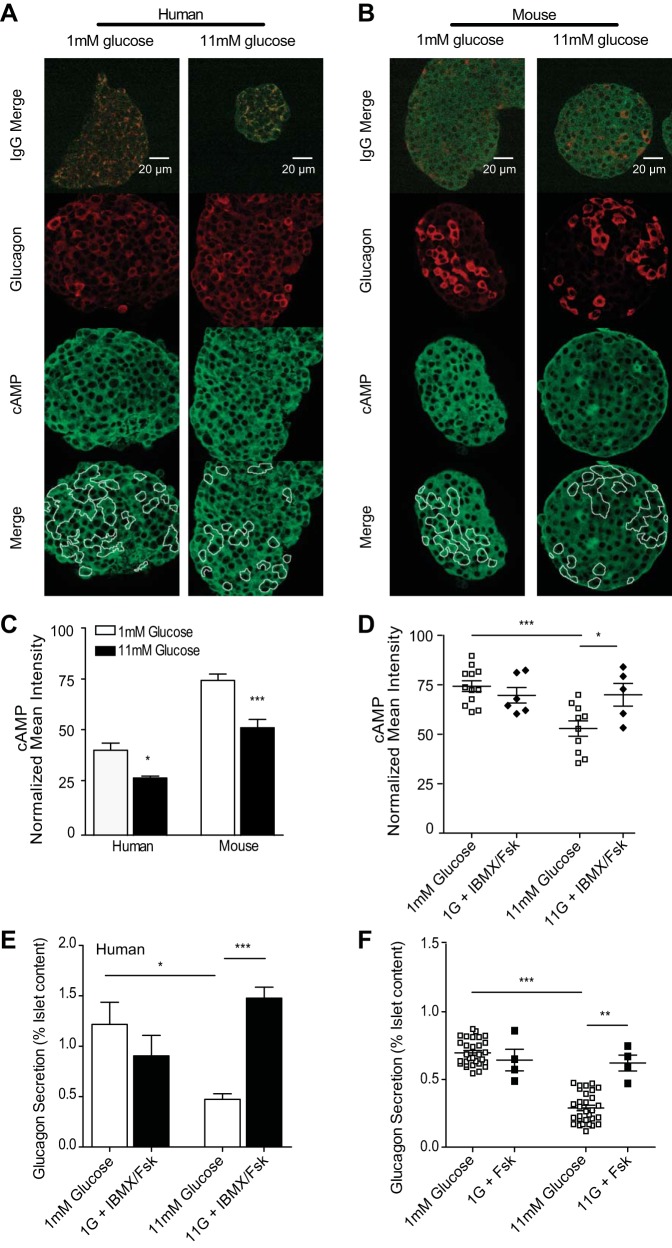

To establish the effect of glucose on α-cell cAMP levels, we used semiquantitative immunofluorescence to measure cAMP in human and murine islets stimulated with low (1 mM) or high (11 mM) glucose (Fig. 1, A–C). Primary antibodies to glucagon were used to identify islet α-cells, and mean intensities of cAMP immunofluorescence for each positive α-cell were background-corrected using preimmune control images. The α-cells form a minority of islet cells, and separating them from the islet changes their function, which means that immunoblotting approaches cannot be used to assay α-cell function. In contrast, immunofluorescence is performed on native tissue, but for a small molecule such as cAMP, special attention must be given to the interpretation of results since unbound cAMP may diffuse away from the cell during fixation. The binding reactions can be described as an equilibrium, and cAMP-binding sites are not saturated in many cellular states (or it could not function as a signaling molecule). Thus, it is not unreasonable to assume that the bound cAMP is a function to the total amount of cAMP over some range of cAMP values. This function is not necessarily linear, but it should be monotonic, which would give a reliable readout of increases and decreases. Although live-cell imaging with a cAMP biosensor could be a useful alternative (9, 27, 38), existing sensors have limited dynamic range (see measurements on purified α-cells below), and we have found the immunofluorescence assay to be reproducible and reliable. Our immunofluorescence measurements show that elevating glucose leads to reduced cAMP levels in both human (by 32.6 ± 3.43%) and murine (by 24.4 ± 3.98%) islet α-cells compared with low-glucose-stimulated islets. As a positive control treatment, we used the phosphodiesterase inhibitor IBMX and adenylyl cyclase activator forskolin to stimulate cAMP. At 11 mM glucose, this treatment led to a significant increase in α-cell cAMP compared with high-glucose-alone control islets (Fig. 1D). In contrast, we did not see increases in cAMP with IBMX/forskolin in α-cells at low glucose, which would be consistent with most of the higher-affinity binding sites for cAMP being occupied under these conditions. In that case, we expect that extra cAMP molecules may diffuse away during fixation and permeabilization. However, as cAMP decreases with elevated glucose, we do see a return to the maximal level of immunofluorescence after addition of IBMX/forskolin. Thus, over the range of immunofluorescence signal decreasing from the resting level (low glucose), we do not find it unreasonable to assume that the cAMP immunofluorescence changes are qualitatively indicative of the actual cAMP changes. As described below (see Fig. 6J), the use of a fluorescence protein biosensor in purified α-cells gives a different sensitivity; due to its KD for cAMP, it shows little response for decreases in cAMP from rest but large responses after stimulation of cAMP.

Fig. 1.

Increasing cAMP overcomes glucose-inhibited glucagon secretion in human and murine α-cells. A–D: immunofluorescence and quantitation of mean intensities from donor human or isolated murine islets statically incubated with 1 (open bars) or 11 mM glucose (black bars) in the absence and presence (D) of 50 μM forskolin (Fsk) or 100 μM 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX) before fixing and staining for glucagon and cAMP. Images from representative human islets (A) and murine islets (B) shown with merged preimmune controls (top); glucagon in red and cAMP in green. C: mean intensities for each channel were normalized to preimmune controls, and data were averaged across donor islets from 4 humans and islets isolated from 10 mice. D: mean intensities from murine islets stained for cAMP and glucagon after treatment with Fsk and IBMX (⧫) or glucose alone (□). Each dot represents the average of 2–5 islets from one mouse. E: glucagon secretion from human islets treated as for immunofluorescence with glucose alone (open bars) or glucose with Fsk and IBMX (black bars). F: murine islet glucagon secretion with glucose alone (□) or glucose with Fsk (■). Error bars represent the SE across mice in each experiment; P values were determined by Student's t-test. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.0001.

Fig. 6.

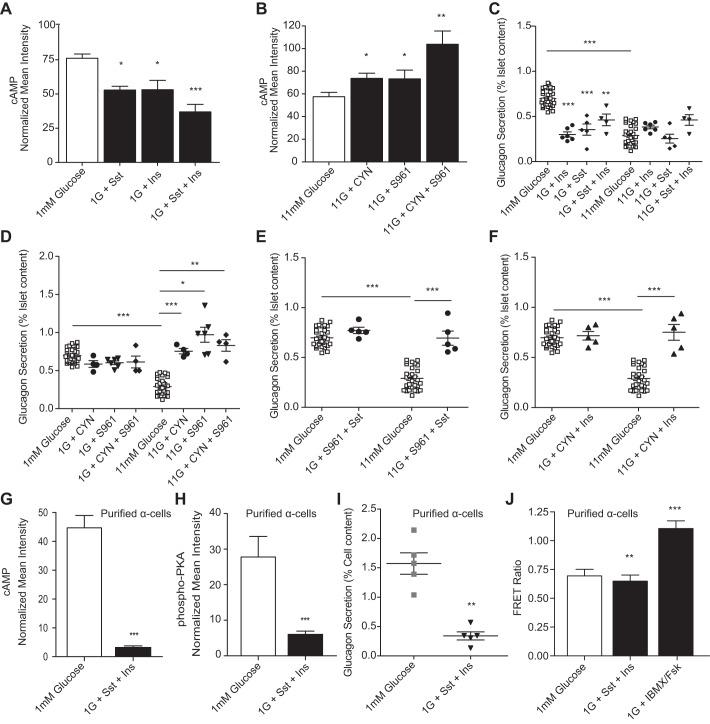

Sst and insulin signaling converges to decrease cAMP in glucose-inhibited glucagon secretion. A and B: normalized mean intensities from islets stimulated with combined 100 nM Sst and 100 nM Ins (black bars), combined 1 μM S961 and 200 nM CYN (black bars), or glucose-only controls (open bars) and then fixed and stained for cAMP and glucagon and normalized to preimmune controls. A: normalized cAMP intensity from islet α-cells treated with 1 mM glucose (n = 13), Sst (n = 6), Ins (n = 5), or Sst with Ins at 1 mM glucose (n = 7). B: normalized cAMP intensity from islet α-cells treated with 11 mM glucose (n = 13), CYN (n = 8), S961 (n = 6), or CYN with S961 at 11 mM glucose (n = 4). C–F: glucagon secretion from islets treated with glucose or glucose in the presence of combinations of Sst, Ins, CYN, and/or S961. C: glucagon secretion from islets stimulated with Ins (●), Sst (⧫), combined Sst and Ins (▼), or glucose alone (□). D: glucagon secretion from islets treated with CYN (●), S961 (▼), CYN and S961 (⧫), or glucose-only controls (□). E: glucagon secretion from islets treated with S961 and Sst (●) or glucose alone (□). F: islet glucagon secretion after treatment with CYN and Ins (▲) or glucose alone (□). G and H: tandem-dimer red fluorescent protein (tdRFP)-expressing α-cells were purified from isolated murine islets (n = 5 mice) and treated with either 1 mM glucose in the absence and presence of 100 nM Sst and 100 nM Ins and either fixed and stained for cAMP, phospho-PKA, and glucagon or assessed for glucagon secretion. G: normalized cAMP intensities from purified α-cells treated with either 1 mM glucose (open bar) or 1 mM glucose with Ins and Sst (black bar). H: normalized phospho-PKA intensities from purified α-cells treated with either 1 mM glucose or 1 mM glucose with Ins and Sst. I: glucagon secretion from isolated α-cells treated in static incubation with 1 mM glucose (gray squares) or 1 mM glucose with 100 nM somatostatin and 100 nM insulin (▼). J: purified α-cells were electroporated with a cAMP Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) biosensor and treated with 1 mM glucose, 1 mM glucose with 100 nM Sst and 100 nM insulin, or 100 μM IBMX and 50 μM Fsk. Error bars represent the SE, and P values were determined by Student's t-test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.0001, unless otherwise indicated.

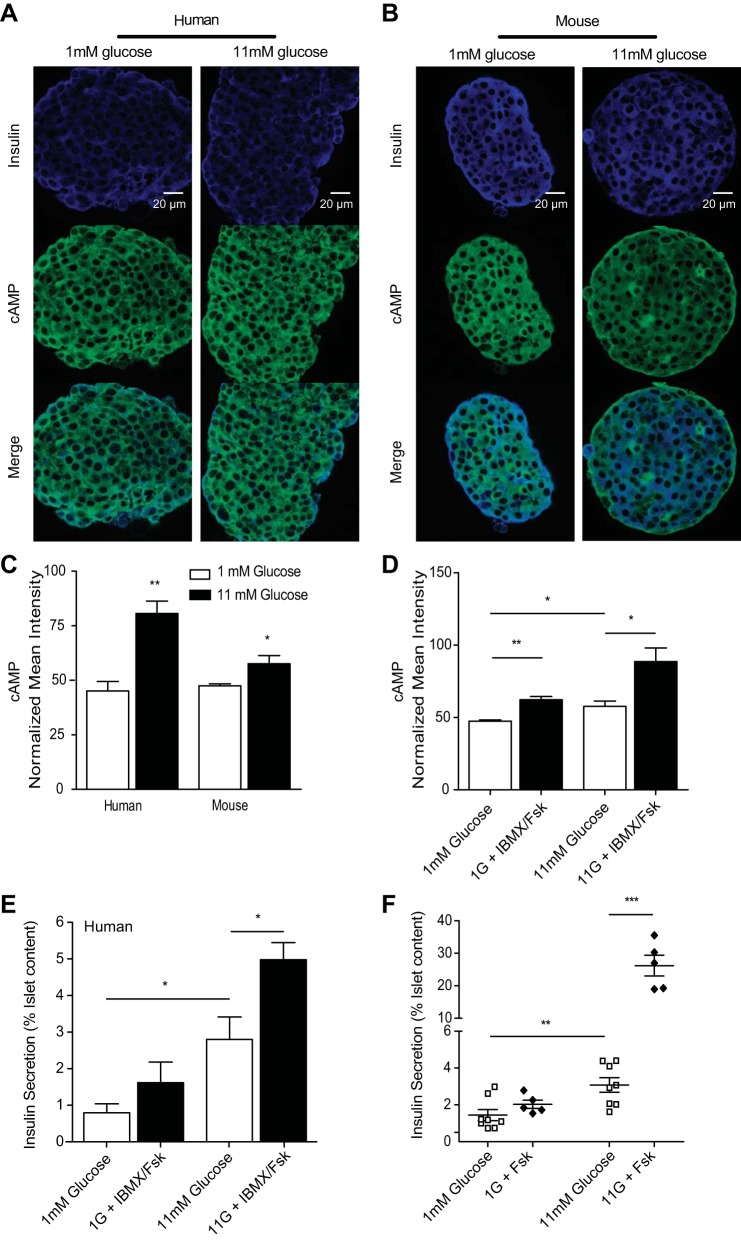

To determine whether forcibly elevating cAMP can overcome glucose suppression, we measured glucagon secretion in the presence of IBMX and/or forskolin. In human islets, we observed a glucose-dependent 3.22 ± 0.14-fold increase in glucagon secretion following IBMX/forskolin treatment at high glucose. In murine islets, the forskolin-treated high-glucose samples exhibited a 2.1 ± 0.06-fold increase in glucagon secretion over high glucose alone (Fig. 1, E and F). To control for cAMP-mediated effects on β-cell regulation, we also measured insulin secretion and found that it was significantly increased 3.76 ± 0.79- and 15.3 ± 2.8-fold in humans and mice, respectively, only at high glucose (Fig. 2). Since cAMP changes appear to regulate glucagon secretion, we examined the islet factors that are expected to affect cAMP levels: somatostatin, which is secreted by the islet δ-cells, and insulin.

Fig. 2.

cAMP is increased with increasing glucose in islet β-cells. A and B: immunofluorescence and quantitation of mean intensities from donor human or isolated murine islets statically incubated with 1 (open bars) or 11 mM glucose (black bars) before fixing and staining for insulin and cAMP. Images from representative human islets (A) and murine islets (B); insulin in blue and cAMP in green. C: mean intensities for each channel were normalized to preimmune controls from their respective tissues, and data were averaged across islet β-cells, as in Fig. 1. D: cAMP mean intensities from murine islet β-cells treated with 1 or 11 mM glucose alone or with IBMX/Fsk. E and F: insulin secretion from islets of 4 human donors (E) or islets isolated from 5 mice (F) that were exposed to 1 or 11 mM glucose in the presence (⧫) and absence (□) of 50 μM forskolin in a static incubation assay. Error bars represent the SE across mice in each experiment, and P values were determined by Student's t-test. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.0001.

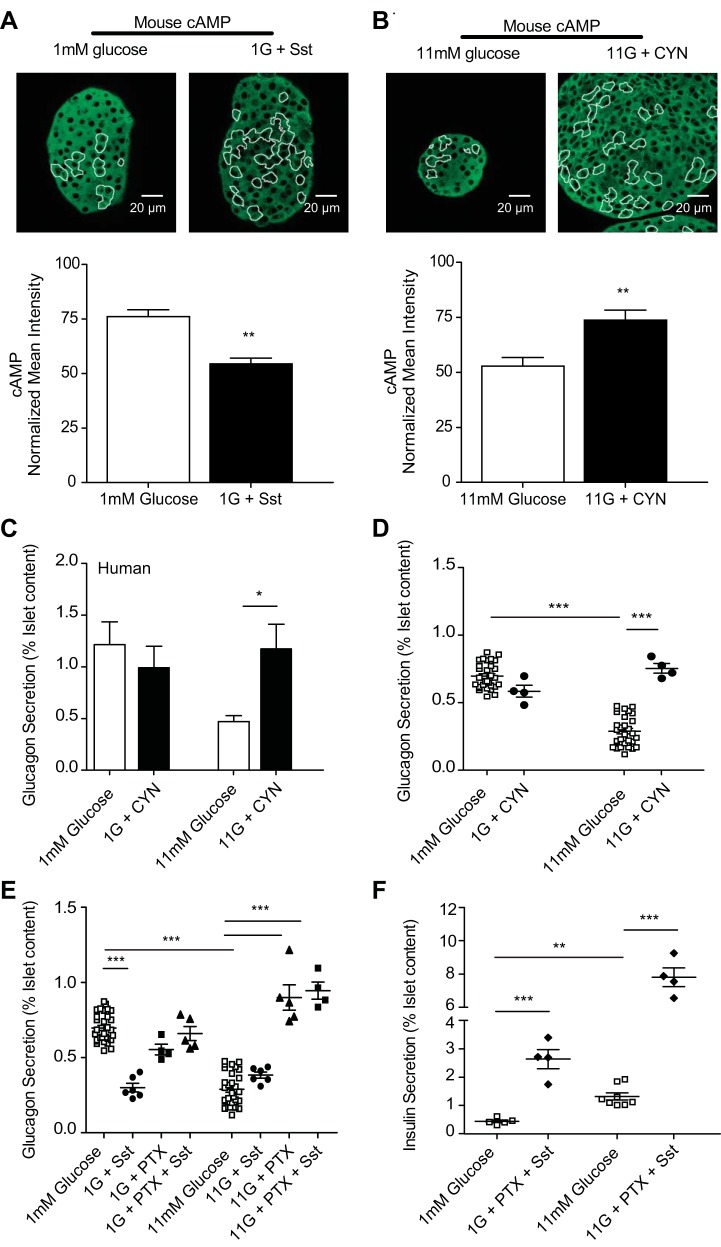

Somatostatin lowers α-cell cAMP production via the SSTR2 Gαi subunit.

Somatostatin, acting via SSTR2, is a potent inhibitor of glucagon secretion (24, 43). To test whether somatostatin inhibits glucagon secretion by decreasing cAMP, we used measured cAMP immunofluorescence in islet α-cells after treatment with somatostatin or CYN154806, a specific SSTR2 antagonist (15). In murine islets treated with somatostatin at low glucose, cAMP was reduced by 39.8 ± 3.1% compared with glucose alone. SSTR2 inhibition by CYN154806 at high glucose elicited a 39.4 ± 4.6% cAMP increase over high glucose alone (Fig. 3, A and B). We also measured glucagon secretion from islets treated with CYN154806 and found a glucose-dependent 2.5 ± 0.41-fold increase in human islet secretion and a 2.61 ± 0.04-fold increase in murine islet secretion at high glucose (Fig. 3, C and D).

Fig. 3.

Somatostatin (Sst) inhibits cAMP production via the Gαi subunit of Sst receptor 2 (SSTR2), which is critical for glucagon suppression. A and B: mean intensities from immunofluorescence studies, where islets were fixed after treatment and stained for cAMP and glucagon and normalized to preimmune controls. Islets were treated with 100 nM Sst at 1 mM glucose (n = 6) or with glucose alone (n = 13) (A) or 200 nM SSTR2 antagonist CYN154806 (CYN) at 11 mM glucose (n = 8) or with glucose alone (n = 10) (B); cAMP in green, glucagon-positive cells outlined in white. C–E: glucagon secretion from donor human or isolated murine islets statically incubated with 200 nM CYN at 1 and 11 mM glucose. C: human islet glucagon secretion (n = 3–5 donors) with glucose alone (open bars) or with CYN (black bars). D: isolated murine islet glucagon secretion with glucose alone (□) and CYN-treated islets (●). E: murine islets pretreated with 1 mg/ml pertussis toxin (PTX) for 18 h were stimulated with 100 nM Sst (▲) at 1 or 11 mM glucose. Control islets treated with glucose alone (□), 100 nM Sst (●), or PTX alone (■) are also displayed. F: insulin secretion from isolated murine islets from E treated with PTX and Sst. Error bars represent the SE across 4–8 mice/experiment, and P values were determined by Student's t-test. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.0001.

We measured glucagon secretion after pertussis toxin (PTX) treatment to inactivate the inhibitory Gα (Gαi) subunit of SSTR2. At low glucose, pretreatment with PTX prevented inhibition by exogenous somatostatin and resulted in no significant difference in glucagon secretion over glucose-alone control islets (Fig. 3E). At high glucose, PTX pretreatment prevented endogenous somatostatin inhibition of glucagon, with a 2.35 ± 0.08-fold increase in secretion over glucose alone. To test whether PTX is directly inhibiting Gαi signaling in α-cells, rather than indirectly through β-cells, we also measured insulin secretion. As reported previously (6), PTX pretreatment prevented inhibition by exogenous somatostatin with a 5.91 ± 0.34- and 5.95 ± 0.58-fold increase in insulin secretion at low and high glucose, respectively (Fig. 3F).

Insulin mediates α-cell cAMP degradation by PDE3B.

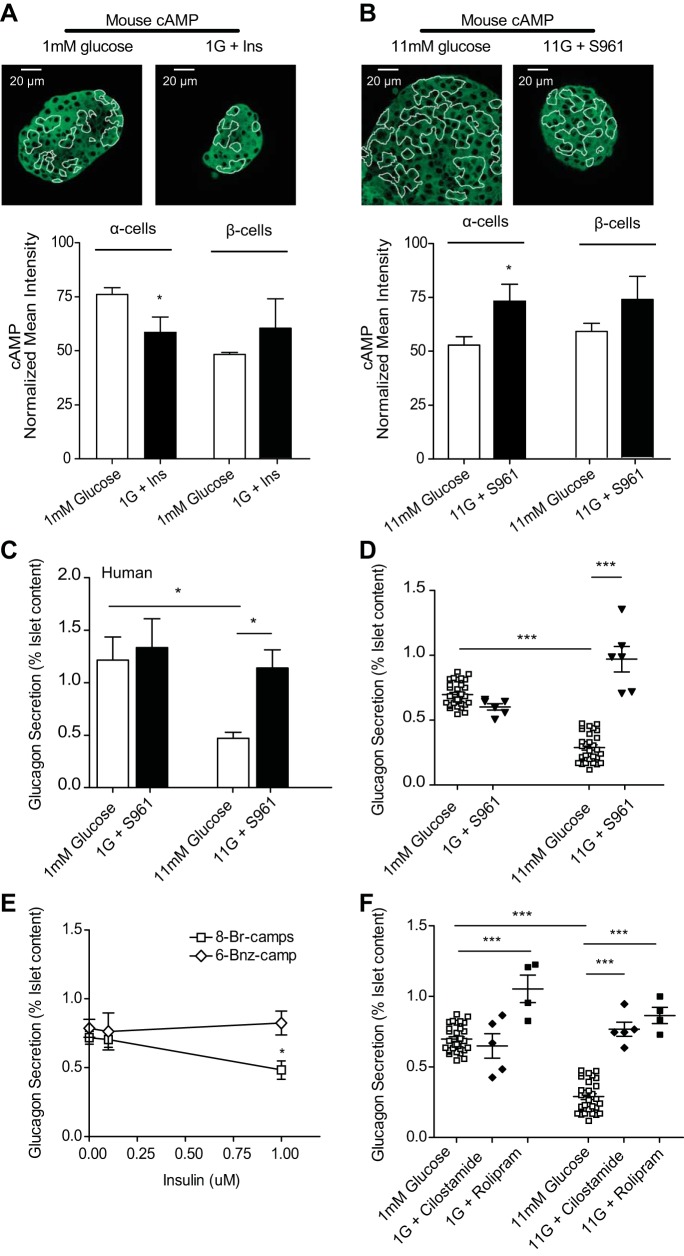

The IR is known to play a role in α-cell physiology (26), and IR signaling can lead to phosphorylation of phosphodiesterases (PDEs), driving degradation of cAMP (45). To test whether this mechanism is utilized in α-cells, we employed immunofluorescence to measure relative cAMP levels. Islets treated with insulin at low glucose exhibited a 23.1 ± 7.2% reduction in α-cell cAMP compared with glucose alone (Fig. 4A). The IR antagonist S961 (40) increased α-cell cAMP at high glucose by 30 ± 7.8% compared with high glucose alone (Fig. 4B). S961-treated islets exhibited glucose-dependent 2.42 ± 0.39- and 3.35 ± 0.1-fold increases in glucagon secretion at high glucose in humans and mice, respectively (Fig. 4, C and D).

Fig. 4.

Insulin drives degradation of cAMP by activating phosphodiesterase 3B (PDE3B) in α-cells and is required for glucose-inhibited glucagon secretion. A and B: mean intensities from immunofluorescence where islets were fixed after treatment and stained for cAMP and glucagon and normalized to preimmune controls. A: islets were treated with 100 nM insulin at 1 mM glucose (n = 5) or glucose alone (n = 13); cAMP in green, glucagon outlined in white. B: islets were treated with 1 μM S961 (n = 6) at 11 mM glucose or with glucose alone (n = 10); cAMP in green, glucagon outlined in white. C–F: glucagon secretion from statically incubated donor human or isolated murine islets treated as above. C: glucagon secretion from 4 donor human islets incubated with 1 μM insulin receptor antagonist S961 at 1 or 11 mM glucose (black bars) and glucose-alone controls (open bars). D: glucagon secretion from isolated murine islets treated with S961 at 1 or 11 mM glucose (▼) or glucose-alone controls (□). E: at 11 mM glucose, glucagon secretion from islets treated with hydrolyzable 300 μM 8-bromoadenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (8-Br-cAMP; □) and no exogenous insulin (n = 6), 100 nM insulin (n = 6), or 1 μM insulin (n = 5); 300 μM nonhydrolyzable N6-benzoyladenosine-3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate sodium salt (6-Bnz-cAMP; ◇) was also tested with no insulin (n = 6), 100 nM insulin (n = 4), or 1 μM insulin (n = 4). F: glucagon secretion from islets treated with PDE inhibitors 250 nM cilostamide (PDE3B; n = 5) or 400 nM rolipram (PDE4; n = 4) at 1 and 11 mM glucose. Error bars represent the SE, and P values were determined by Student's t-test. *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.0001.

To determine whether insulin decreases glucagon secretion via PDE activation, we measured glucagon secretion from islets in the presence of insulin and the PDE inhibitor IBMX. At low and high glucose, IBMX treatment prevented exogenous insulin from inhibiting glucagon secretion compared with insulin alone, which is comparable with treatment with IBMX alone. We also measured glucagon secretion in the presence of either a hydrolyzable (8-Br-cAMP) or nonhydrolyzable (6-Bnz-cAMP) cAMP analog together with insulin at high glucose (Fig. 4E). Glucagon secretion was not significantly different from glucose with 8-Br-cAMP for islets treated with 100 nM insulin. However, 1 μM insulin decreased glucagon secretion from islets treated with 8-Br-cAMP 1.5 ± 0.15-fold. Islets treated with the nonhydrolyzable 6-Bnz-cAMP were unaffected by either concentration of exogenous insulin.

To identify whether PDE3B or PDE4 (both of which are expressed in α-cells) (5) are involved in glucose suppression of glucagon, we measured glucagon secretion in the presence of specific inhibitors for PDE3B (cilostamide) and PDE4 (rolipram) (Fig. 4F). Cilostamide treatment showed a glucose-dependent 2.65 ± 0.86-fold increase in glucagon secretion at high glucose. Rolipram increased glucagon secretion at both low and high glucose, with fold increases of 1.51 ± 0.1 and 2.98 ± 0.06, respectively. Since glucagon secretion appears to be inhibited by cAMP lowering, we next examined what downstream targets of cAMP might be involved.

A decrease in cAMP and PKA is required for glucagon suppression.

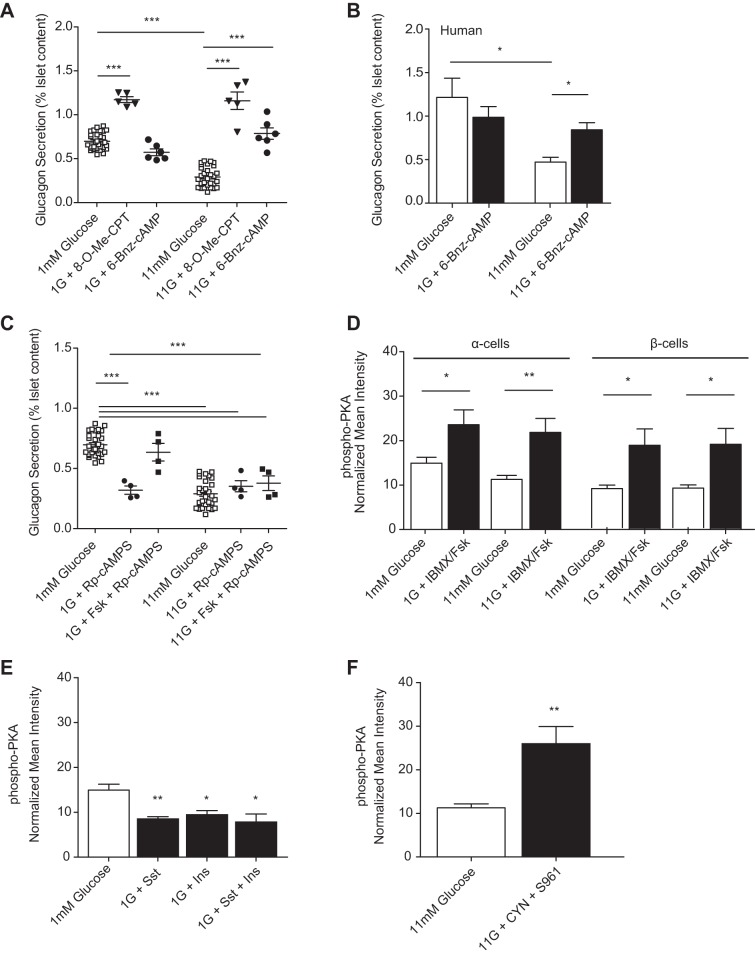

The two proximal targets for cAMP signaling are protein kinase A (PKA) and exchange protein activated by cAMP (Epac). To determine whether one of these targets is preferentially decreased with glucose, we measured secretion from murine islets in the presence and absence of a PKA- (6-Bnz-cAMP) or Epac-specific (8-pCPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP) agonist (Fig. 5A). Epac activation produced a 1.68 ± 0.03-fold increase in glucagon secretion over low glucose alone and a 4.0 ± 0.10-fold increase over high glucose alone. PKA activation, however, displayed glucose dependence with 2.77 ± 0.08-fold increased glucagon secretion only at high glucose over glucose alone. Additionally, treatment with the PKA agonist 6-Bnz-cAMP led to a 1.79 ± 0.12-fold glucose-dependent increase in secretion from human islets at high glucose (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Insulin (Ins) and Sst also decrease PKA glucose-dependently, which must be lowered for glucagon suppression. A: glucagon secretion from murine islets after stimulation with glucose alone (□), 300 μM exchange protein activated by cAMP agonist 8-(4-chlorophenylthio)-2′-O-methyladenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate monosodium hydrate (8-O-Me-CPT; ▼), or 300 μM PKA agonist 6-Bnz-cAMP (●) at 1 and 11 mM glucose. B: human islet glucagon secretion after stimulation with glucose alone (open bars) or 300 μM PKA agonist 6-Bnz-cAMP (black bars) at 1 and 11 mM glucose. C: glucagon secretion from murine islets treated with glucose alone (□), 50 μM forskolin, forskolin and 100 μM PKA-specific antagonist Rp-cAMPS (■), or Rp-cAMPS alone (●). D–F: normalized mean intensities from islets or purified α-cells treated with glucose alone or with 50 μM Fsk and 100 μM IBMX, 100 nM Sst, 100 nM Ins, combined somatostatin and insulin, or combined 200 nM CYN and 1 μM S961 and then fixed and stained for phospho-PKA and glucagon. D: normalized phospho-PKA intensity from islet α-cells or β-cells treated at 1 (open bars) or 11 mM glucose (black bars) with IBMX/Fsk (n = 6) or alone (n = 7). E: normalized phospho-PKA (n = 6) intensity from islet α-cells incubated with 1 mM glucose alone (n = 7; open bar) or in the presence of Sst, Ins, or Sst with Ins (n = 5, 4, and 5, respectively; black bars). F: normalized phospho-PKA (n = 4) intensity from islet α-cells treated with 11 mM glucose alone (open bar) or with CYN and S961 (black bar). Error bars represent the SE across 4–8 mice/experiment, and P values were determined by Student's t-test. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.0001.

To determine whether PKA inhibition could rescue glucagon suppression with glucose, we measured glucagon secretion from murine islets treated with the specific PKA inhibitor Rp-cAMPS in the presence and absence of forskolin. At high glucose, PKA inhibition reduced forskolin-stimulated glucagon secretion to levels comparable with high glucose alone and inhibited glucagon secretion at low glucose (Fig. 5C).

To measure PKA activation by cAMP, we imaged immunofluorescence of an antibody against phosphorylated PKA (phospho-PKA). Phospho-PKA was reduced by 24.5 ± 1.3% in islet α-cells treated with high glucose compared with low glucose alone. IBMX/forskolin increased α-cell phospho-PKA by 28.9 ± 1.3% at low glucose and 73.8 ± 3.1% at high glucose compared with glucose alone (Fig. 5D). In islets treated with somatostatin, insulin, or the combination of these, phospho-PKA was reduced by 41 ± 1.3, 34.4 ± 1.25, and 39.2 ± 1.83% compared with low glucose alone, respectively (Fig. 5E). Inhibiting both SSTR2 and IR with CYN154806 and S961 yielded an increase in phospho-PKA of 130 ± 3.93% over high glucose alone in islet α-cells (Fig. 5F).

Somatostatin and insulin lower α-cell cAMP and inhibit glucagon secretion.

We tested whether combined somatostatin and insulin synergistically lower cAMP in α-cells. In murine islets treated with both somatostatin and insulin, cAMP was reduced by 56.8 ± 3.07% compared with 1 mM glucose alone and by 39.6 ± 4.6 and 43.8 ± 7.18% compared with somatostatin and insulin alone, respectively (Fig. 6A). Islets treated with CYN154806 and S961 exhibited an 80.4 ± 11.8% increase in mean intensity for cAMP compared with 11 mM glucose alone (Fig. 6B).

To determine whether the effects of somatostatin and insulin on glucagon secretion are additive, murine islets were treated with glucose in the presence and absence of somatostatin and insulin or receptor antagonists CYN154806 and S961 (Fig. 6, C and D). Combined somatostatin and insulin reduced glucagon secretion at low glucose 2.07 ± 0.33-fold compared with glucose alone and 1.45 ± 0.16- and 1.29 ± 0.16-fold compared with somatostatin or insulin alone, respectively. Combined CYN154806 and S961 increased glucagon secretion 2.82 ± 0.47-fold over high glucose alone.

To explore the interdependence of somatostatin and insulin signaling, we measured glucagon secretion from murine islets with S961 in the presence of exogenous somatostatin. At high glucose, IR inhibition prevented exogenous somatostatin from suppressing glucagon secretion with a 2.40 ± 0.07-fold increase over glucose alone (Fig. 6E). Next, we measured secretion from islets exposed to CYN154806 and insulin. At high glucose, SSTR2 inhibition prevented insulin from suppressing glucagon secretion, which was increased 2.59 ± 0.08-fold over glucose alone (Fig. 6F).

Previous work demonstrated that neither insulin nor somatostatin alone inhibited glucagon secretion from sorted α-cells (31). We measured cAMP and phospho-PKA immunofluorescence and glucagon secretion from purified α-cells treated with or without combined somatostatin and insulin. The dispersed α-cells treated with somatostatin and insulin exhibited a 92 ± 8.6% decrease in cAMP, a 77 ± 11.6% decrease in phospho-PKA (Fig. 6, G and H), and a 4.61 ± 0.41-fold decrease in glucagon secretion (Fig. 6I) compared with glucose alone. We also expressed a FRET-based cAMP sensor (27) in dispersed α-cells and measured a 7 ± 0.06% decrease in cAMP following treatment with somatostatin and insulin and a 59 ± 0.07% increase after treatment with IBMX/forskolin (Fig. 6J). Although the cAMP biosensor data has a high signal-to-noise ratio, the KD of this biosensor appears to be well above the cAMP resting level in α-cells. This leads to the relatively poorer sensitivity to decreases in cAMP, with a lareger response to elevation in cAMP (opposite of the apparent sensitivity in our immunofluorescence measurements).

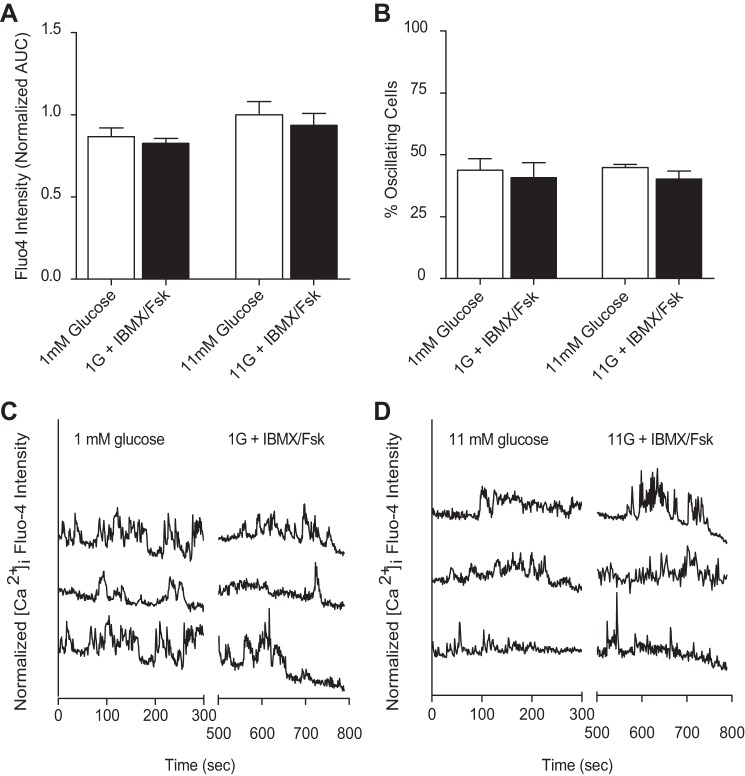

α-Cell cAMP signaling is independent of intracellular calcium.

Finally, we wanted to determine whether cAMP effects on α-cell secretion could be mediated by [Ca2+]i. We imaged the Ca2+ indicator dye fluo 4 in murine-isolated islets with tdRFP-expressing α-cells (31). Fluo 4 was monitored over time (35) in islets treated with glucose alone or with IBMX/forskolin. No significant differences in [Ca2+]i were observed between low and high glucose or between the IBMX/forskolin-treated and untreated groups (Fig. 7A). Additionally, the percentage of oscillating α-cells was unaffected by change in glucose concentration and treatment with IBMX/forskolin (Fig. 7, B–D).

Fig. 7.

cAMP stimulation is independent of changes in α-cell intracellular Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i). Isolated murine islets were exposed to 1 or 11 mM glucose in the absence (open bars) and presence (black bars) of 50 μM Fsk or 100 μM IBMX and subjected to Ca2+ imaging via fluo 4 intensity measurements. A: [Ca2+]i as measured by fluo 4 intensity [area under the curve (AUC)] in murine isolated islets treated with glucose alone (open bars) or in the presence of 50 μM Fsk and 100 μM IBMX (black bars). B: mean %cells with oscillations in Ca2+ as a function of glucose, where α-cells were identified by tdRFP expression in 2–4 islets from 4 mice. C and D: representative [Ca2+]i response to glucose alone or IBMX/Fsk stimulation at 1 (C) and 11 mM (D) glucose. Time course traces are offset for clarity.

DISCUSSION

We examined the role of cAMP signaling in glucose-inhibited α-cell glucagon secretion. Our data show that cAMP levels are reduced with increasing glucose in both human and mouse islet α-cells (Fig. 1). This is in contrast to β-cells, where cAMP increases with increasing glucose (Fig. 2). We used immunofluorescence for these studies, which is an atypical approach for the analysis of molecular concentration changes, but one that we have previously used effectively for such purposes (see, e.g., Ref. 33). As described in results, the immunofluorescence measurement of cAMP appears to give a useful dynamic range over the glucose concentrations where glucagon secretion is inhibited. Parallel experiments using a fluorescence protein biosensor in purified α-cells, on the other hand, yielded small responses for decreases in cAMP but large responses after cAMP stimulation (Fig. 6J). These data show the difficulties of matching the affinities of biosensor assays with the functionally important levels in the cell. We have relied mostly on immunofluorescence as a relative assessment of cAMP, which is not ideal but has yielded reliable and reproducible results from single α-cells within intact islets. Although there are no theoretical advantages to using immunofluorescence over live imaging, it is currently difficult to implement live-cell biosensor experiments in a physiologically relevant model of glucagon inhibition. Ideally, mouse models expressing a range of well-characterized cAMP biosensors in defined cell types would be available to address these questions in an optimal way. In our work, the immunofluorescence experiments were done to support the conclusions drawn from the secretion data, which is the strongest evidence of our findings.

We combined these measurements with established procedures for manipulating cAMP levels and signaling in cells (see Figs. 1, 2, and 4). In all cases where the cAMP immunofluorescence is less than the apparent saturated value (what is measured at 1 mM glucose), the measured cAMP immunofluorescence changes are also consistent with changes in glucagon secretion. Previous papers describing cAMP effects in α-cells have led to conclusions different but not mutually exclusive from those presented here. However, the experimental procedures and goals of those experiments were quite different from the current study. For example, elevating glucose to >11 mM has been shown to induce slow oscillations of intracellular cAMP in some but not all of the α-cells (38). At very high glucose levels, cAMP increases may occur due to any of a number of membrane-bound and soluble adenylyl cyclases, so we have focused on a physiological glucose range of <11 mM. In fact, the dysregulation of glucagon inhibition at very high glucose levels underscores the importance of maintaining a careful balance between the molecular regulators of glucagon secretion, including insulin and somatostatin. Still, the temporal dynamics of cAMP oscillations may play a role in α-cell function despite a lack of evidence in the literature of any synchronized α-cell activity. We performed measurements of static cAMP levels that correlate with glucagon secretion from intact islets, but these data do not address any potentially important action of temporal cAMP dynamics on α-cell function. Another study (9) showed an inhibition of glucagon secretion upon application of low concentration of forskolin, which also elevated cAMP. Our data are contradictory to those experiments, but their glucagon secretion data were collected under glucose starvation conditions, which may not produce the same results. Furthermore, their cAMP measurements were performed in the presence of IBMX, which was not included in the secretion measurements. Finally, their cAMP measurements were done in whole islets before the elucidation of the important differences in cAMP regulation between α- and β-cells (38). So although there are still many conflicting data on α-cell cAMP regulation, the experimental conditions between the few published papers appear sufficiently different as to preclude a direct comparison.

Forced elevation of cAMP overcomes the natural inhibition of glucagon secretion caused by elevated glucose. This suggests that decreased cAMP signaling plays a role in glucose-inhibited glucagon secretion, especially since increasing cAMP does not affect [Ca2+]i oscillations (Fig. 7) in the α-cells. This is consistent with other reports of α-cell cAMP regulation, which has been shown to differ between α- and β-cells (13, 17). To account mechanistically for these observations, we hypothesize a role for other islet/cell secretions known to affect cAMP, such as somatostatin or insulin.

SSTR2 is the functionally dominant receptor in α-cells for humans and mice (24). We determined whether somatostatin, via SSTR2, decreases α-cell cAMP levels and inhibits glucagon secretion (Fig. 3). At high glucose levels, the SSTR2-specific antagonist increased glucagon secretion from both human and murine islets only at high glucose (Fig. 3, C and D). Furthermore, after treating the islets with pertussis toxin to prevent the inhibitory Gαi subunit of the receptor, somatostatin no longer inhibited glucagon secretion (Fig. 3E). Together, these data are all consistent with a model where somatostatin is required for glucose-inhibited glucagon secretion via the Gαi subunit of the SSTR2, which decreases cAMP production by inhibiting adenylyl cyclases. However, somatostatin is insufficient to inhibit glucagon secretion from purified α-cells, which led us to hypothesize a cooperative mechanism involving multiple signaling pathways.

Another pathway could involve the IR, as PI3K inhibition has been reported to block insulin-mediated glucagon inhibition (7, 34), and the PI3K target Akt is required for glucose-inhibited glucagon secretion (11, 26). Other cell types are regulated by insulin signaling through phosphodiesterases to decrease cAMP and limit lipolysis (1, 10). We found that insulin decreased cAMP at high glucose (Fig. 4A). In contrast, antagonizing IR produced a significant increase in cAMP at high glucose. Glucagon secretion from murine and human islets treated with IR antagonist was increased in correlation with cAMP levels, and the inhibitory effect of glucose was lost (Fig. 4, C and D). This correlation pointed to a putative role for insulin activation of PDEs. To test this hypothesis, we treated islets with cAMP analogs and various concentrations of insulin, similar to work by Beebe et al. (2). The suppression of glucagon secretion by insulin was lost in the presence of a PDE-resistant cAMP analog (Fig. 4E). Glucagon secretion from islets treated with a hydrolyzable cAMP analog was partially rescued at high glucose only at high concentrations of insulin (Fig. 4E). All of these observations support a role for PDE in inhibiting glucagon secretion. Two PDEs found predominantly in islet α-cells are PDE3 and PDE4 (5), but only the PDE3B-specific inhibitor cilostamide elicited a significant glucose dose-dependent increase in glucagon secretion (Fig. 4F). In contrast, the PDE4-selective inhibitor rolipram stimulated glucagon secretion at all glucose levels. These data together support a model where glucose-stimulated insulin secretion from β-cells acts through PI3K to phosphorylate Akt and PDE3B, much like adipocytes (10), and decreases α-cell cAMP and glucagon secretion. Still, insulin alone is insufficient to inhibit glucagon secretion from purified α-cells (31).

Little is known about the role of PDE4 in regulating glucagon secretion directly, although one study suggests that PDE4 plays a role in glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) release from intestinal L cells (41), as PDE4 inhibitors given to db/db mice increased plasma GLP-1 and insulin and lowered blood glucose. Those authors concluded that these inhibitors augmented GLP-1 levels presumably through increased secretion. The study did not measure glucagon levels or address the possibility that the PDE4 inhibitor could be working directly on the islet, so it may also be affecting the α-cells and glucagon secretion. However, the study did demonstrate a glucose-independent role for PDE4 in regulating islet function, which is consistent with what we show in this work.

Both somatostatin and insulin signaling affect cAMP in the same direction, and the combination of insulin and somatostatin decreases cAMP significantly more than either insulin or somatostatin alone at low glucose (Fig. 6A). Inhibiting both insulin and somatostatin receptors increases cAMP significantly more than either antagonist alone at high glucose (Fig. 6B). Importantly, the combination of these two factors is sufficient to decrease cAMP (Fig. 6, G and J) and inhibit glucagon secretion (Fig. 6I) from purified α-cells even in the absence of normal islet architecture.

The two primary downstream cAMP effector proteins PKA and Epac are important players in islet secretory dynamics (4, 14, 17, 19, 22). To test their roles in α-cell cAMP signaling, we measured glucagon secretion in the presence and absence of specific PKA or Epac activators. Epac stimulation increases glucagon secretion independent of glucose concentration, whereas PKA activation only potentiates secretion at high glucose in murine and human islets (Fig. 5, A and B). Forskolin stimulation of glucagon secretion was also partially suppressed by PKA inhibition (Fig. 5C). These data are consistent with decreased PKA signaling being a required step in glucose-inhibited glucagon secretion, and increasing PKA activity is sufficient to overcome this inhibition.

Epac2 is a target of cAMP that has been implicated in insulin secretion as a regulator of the readily releasable pool of vesicles trafficking to the membrane. In the β-cells, Epac2 can be activated to increase insulin secretion independently of glucose concentration. However, the data concerning the role of Epac2 in α-cell physiology are much less clear. Studies in Epac2-null mice demonstrated by De Marinis et al. (9) showed that adrenaline regulation of glucagon secretion at low glucose is Epac2 dependent, but its role in α-cell glucagon regulation by glucose was not studied. Thus, the mechanism of action for Epac2 remains to be elucidated in α-cells. Our data suggest that Epac2 activation is independent of glucose, which is consistent with the previous studies.

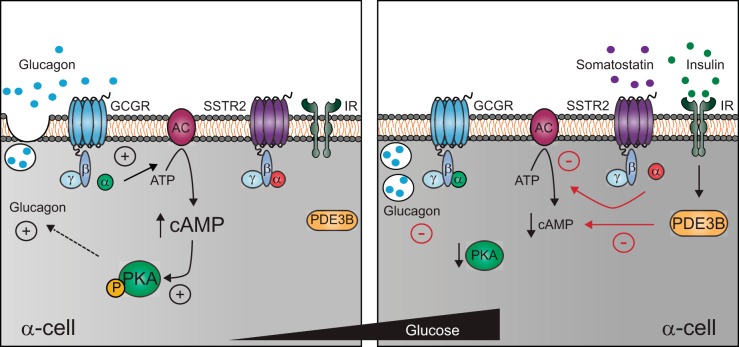

Taken together, the data lead to a novel model where activation of both SSTR2 and IR is required for glucose-inhibited glucagon secretion from islet α-cells (Fig. 8). SSTR2 decreases cAMP by inhibiting its synthesis, whereas the IR activates PDE3B to degrade any remaining cAMP. This model is consistent with temporal glucagon responses, which are relatively rapid after a step increase of glucose but much slower in recovery after glucose is removed (30). In this case, the PDE can rapidly degrade existing cAMP, but the formation of new cAMP as glucose decreases will be limited by the throughput of adenylyl cyclases (3, 29). This model depends on cAMP signaling and does not require any changes in intracellular Ca2+, consistent with previous reports (30, 38). At low glucose, exocytosis requires Ca2+ (9), but our data support a model where these pathways are uncoupled as glucose increases. Although our data suggest that cAMP inhibits glucagon secretion via PKA signaling, the downstream targets of PKA that regulate exocytosis remain unknown.

Fig. 8.

Schematic of glucagon inhibition via insulin and somatostatin's effects on cAMP in α-cells at low and high glucose. Illustration of the stimulatory effect of cAMP via PKA on glucagon secretion from the pancreatic α-cell (left) and the inhibitory roles of insulin and somatostatin in lowering cAMP signaling at high glucose (right). In response to hypoglycemia, glucagon secretion is stimulated in a cAMP and Ca2+-dependent manner. As plasma glucose rises, ATP and cAMP production increase, as well as protein kinase A (PKA) activation, which must be inhibited for glucagon secretion to be suppressed in the α-cells. Somatostatin and insulin are released in response to rising glucose from the δ- and β-cells, respectively. Somatostatin binds the SSTR2 receptor and prevents further production of cAMP via the inhibitory G protein αi-subunit. Additionally, insulin activates PDE3B to drive degradation of cAMP and inhibit PKA signaling. The coordination of somatostatin and insulin to reduce cAMP-dependent exocytosis is required for the inhibition of glucagon secretion at high glucose levels. GCGR, glucagon receptor; P, phosphorylated PKA.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants to D. W. Piston: R01-DK-53434, R01-DK-98659, S10-RR-25649, and S10-OD-10681. Equipment and technical assistance were provided by the Vanderbilt Flow Cytometry Shared Resource [supported by the Vanderbilt Ingram Cancer Center (CA-68485) and Vanderbilt Digestive Disease Research Center (DK-58404)] and the Vanderbilt Diabetes Research and Training Center (DK-020593).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A.D.E., A.U., and D.W.P. conception and design of research; A.D.E. and A.U. performed experiments; A.D.E., A.U., and D.W.P. analyzed data; A.D.E. and D.W.P. interpreted results of experiments; A.D.E. and A.U. prepared figures; A.D.E. drafted manuscript; A.D.E., A.U., and D.W.P. edited and revised manuscript; A.D.E., A.U., and D.W.P. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Technical assistance with animals was provided by Christopher Reissaus and Tara Schwetz. Human islets were obtained from the IIDP, sponsored by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, with additional support from the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation International. We thank Jackie Corbin for the gifts of rolipram and cilostamide.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmad F, Lindh R, Tang Y, Ruishalme I, Ost A, Sahachartsiri B, Strålfors P, Degerman E, Manganiello VC. Differential regulation of adipocyte PDE3B in distinct membrane compartments by insulin and the beta3-adrenergic receptor agonist Cl316243: effects of caveolin-1 knockdown on formation/maintenance of macromolecular signalling complexes. Biochem J 424: 399–410, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beebe SJ, Redmon JB, Blackmore PF, Corbin JD. Discriminative insulin antagonism of stimulatory effects of various cAMP analogs on adipocyte lipolysis and hepatocyte glycogenolysis. J Biol Chem 260: 15781–15788, 1985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bender AT, Beavo JA. Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases: molecular regulation to clinical use. Pharmacol Rev 58: 488–520, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benninger RK, Head WS, Zhang M, Satin LS, Piston DW. Gap junctions and other mechanisms of cell-cell communication regulate basal insulin secretion in the pancreatic islet. J Physiol 589: 5453–5466, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bramswig NC, Everett LJ, Schug J, Dorrell C, Liu C, Luo Y, Streeter PR, Naji A, Grompe M, Kaestner KH. Epigenomic plasticity enables human pancreatic alpha to beta cell reprogramming. J Clin Invest 123: 1275–1284, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cawthorn EG, Chan CB. Effect of pertussis toxin on islet insulin secretion in obese (fa/fa) Zucker rats. Mol Cell Endocrinol 75: 197–204, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen J, Ostenson CG. Glucagon release is regulated by tyrosine phosphatase and PI3-kinase activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 325: 555–560, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng-Xue R, Gomez-Ruiz A, Antoine N, Noel LA, Chae HY, Ravier MA, Chimienti F, Schuit FC, Gilon P. Tolbutamide controls glucagon release from mouse islets differently than glucose: involvement of KATP channels from both alpha-cells and delta-cells. Diabetes 62: 1612–1622, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Marinis YZ, Salehi A, Ward CE, Zhang Q, Abdulkader F, Bengtsson M, Braha O, Braun M, Ramracheya R, Amisten S, Habib AM, Moritoh Y, Zhang E, Reimann F, Rosengren AH, Shibasaki T, Gribble F, Renstrom E, Seino S, Eliasson L, Rorsman P. Glp-1 inhibits and adrenaline stimulates glucagon release by differential modulation of N- and L-type Ca2+ channel-dependent exocytosis. Cell Metab 11: 543–553, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Degerman E, Ahmad F, Chung YW, Guirguis E, Omar B, Stenson L, Manganiello V. From PDE3B to the regulation of energy homeostasis. Curr Opin Pharmacol 11: 676–682, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diao J, Asghar Z, Chan CB, Wheeler MB. Glucose-regulated glucagon secretion requires insulin receptor expression in pancreatic alpha-cells. J Biol Chem 280: 33487–33496, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dorrell C, Schug J, Lin CF, Canaday PS, Fox AJ, Smirnova O, Bonnah R, Streeter PR, Stoeckert CJ Jr, Kaestner KH, Grompe M. Transcriptomes of the major human pancreatic cell types. Diabetologia 54: 2832–2844, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dyachok O, Idevall-Hagren O, Sågetorp J, Tian G, Wuttke A, Arrieumerlou C, Akusjärvi G, Gylfe E, Tengholm A. Glucose-induced cyclic AMP oscillations regulate pulsatile insulin secretion. Cell Metab 8: 26–37, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dyachok O, Sågetorp J, Isakov Y, Tengholm A. cAMP oscillations restrict protein kinase A redistribution in insulin-secreting cells. Biochem Soc Trans 34: 498–501, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feniuk W, Jarvie E, Luo J, Humphrey PP. Selective somatostatin sst(2) receptor blockade with the novel cyclic octapeptide, CYN-154806. Neuropharmacology 39: 1443–1450, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Franklin I, Gromada J, Gjinovci A, Theander S, Wollheim CB. Beta-cell secretory products activate alpha-cell ATP-dependent potassium channels to inhibit glucagon release. Diabetes 54: 1808–1815, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gromada J, Bokvist K, Ding WG, Barg S, Buschard K, Renström E, Rorsman P. Adrenaline stimulates glucagon secretion in pancreatic A-cells by increasing the Ca2+ current and the number of granules close to the L-type Ca2+ channels. J Gen Physiol 110: 217–228, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gromada J, Franklin I, Wollheim CB. Alpha-cells of the endocrine pancreas: 35 years of research but the enigma remains. Endocr Rev 28: 84–116, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hatakeyama H, Takahashi N, Kishimoto T, Nemoto T, Kasai H. Two cAMP-dependent pathways differentially regulate exocytosis of large dense-core and small vesicles in mouse beta-cells. J Physiol 582: 1087–1098, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hauge-Evans AC, King AJ, Carmignac D, Richardson CC, Robinson IC, Low MJ, Christie MR, Persaud SJ, Jones PM. Somatostatin secreted by islet delta-cells fulfills multiple roles as a paracrine regulator of islet function. Diabetes 58: 403–411, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hauge-Evans AC, King AJ, Fairhall K, Persaud SJ, Jones PM. A role for islet somatostatin in mediating sympathetic regulation of glucagon secretion. Islets 2: 341–344, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Idevall-Hagren O, Barg S, Gylfe E, Tengholm A. cAMP mediators of pulsatile insulin secretion from glucose-stimulated single beta-cells. J Biol Chem 285: 23007–23018, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jarrousse C, Rosselin G. Regulation by glucose and cyclic nucleotides of the glucagon and insulin release induced by amino acids. Diabete Metab 1: 135–142, 1975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kailey B, Van De Bunt M, Cheley S, Johnson PR, Macdonald PE, Gloyn AL, Rorsman P, Braun M. SSTR2 is the functionally dominant somatostatin receptor in human pancreatic β- and α-cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 303: E1107–E1116, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Katakami N, Kim YS, Kawamori R, Yamasaki Y. The phosphodiesterase inhibitor cilostazol induces regression of carotid atherosclerosis in subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus: principal results of the Diabetic Atherosclerosis Prevention by Cilostazol (DAPC) study: a randomized trial. Circulation 121: 2584–2591, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kawamori D, Kurpad AJ, Hu J, Liew CW, Shih JL, Ford EL, Herrera PL, Polonsky KS, Mcguinness OP, Kulkarni RN. Insulin signaling in alpha cells modulates glucagon secretion in vivo. Cell Metab 9: 350–361, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klarenbeek JB, Goedhart J, Hink MA, Gadella TW, Jalink K. A mTurquoise-based cAMP sensor for both FLIM and ratiometric read-out has improved dynamic range. PLoS One 6: e19170, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koh DS, Cho JH, Chen L. Paracrine interactions within islets of langerhans. J Mol Neurosci 48: 429–440, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lam AJ, St-Pierre F, Gong Y, Marshall JD, Cranfill PJ, Baird MA, McKeown MR, Wiedenmann J, Davidson MW, Schnitzer MJ, Tsien RY, Lin MZ. Improving FRET dynamic range with bright green and red fluorescent proteins. Nat Methods 9: 1005–1012, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Le Marchand SJ, Piston DW. Glucose decouples intracellular Ca2+ activity from glucagon secretion in mouse pancreatic islet alpha-cells. PLoS One 7: e47084, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Le Marchand SJ, Piston DW. Glucose suppression of glucagon secretion: metabolic and calcium responses from alpha-cells in intact mouse pancreatic islets. J Biol Chem 285: 14389–14398, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liang L, Beshay E, Prud'homme GJ. The phosphodiesterase inhibitors pentoxifylline and rolipram prevent diabetes in NOD mice. Diabetes 47: 570–575, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Niswender KD, Postic C, Jetton TL, Bennett BD, Piston DW, Efrat S, Magnuson MA. Cell-specific expression and regulation of a glucokinase gene locus transgene. J Biol Chem 272: 22564–22569, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ravier MA, Rutter GA. Glucose or insulin, but not zinc ions, inhibit glucagon secretion from mouse pancreatic alpha-cells. Diabetes 54: 1789–1797, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rocheleau JV, Walker GM, Head WS, McGuinness OP, Piston DW. Microfluidic glucose stimulation reveals limited coordination of intracellular Ca2+ activity oscillations in pancreatic islets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 12899–12903, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schwetz TA, Ustione A, Piston DW. Neuropeptide Y and somatostatin inhibit insulin secretion through different mechanisms. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 304: E211–E221, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Strowski MZ, Parmar RM, Blake AD, Schaeffer JM. Somatostatin inhibits insulin and glucagon secretion via two receptors subtypes: an in vitro study of pancreatic islets from somatostatin receptor 2 knockout mice. Endocrinology 141: 111–117, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tian G, Sandler S, Gylfe E, Tengholm A. Glucose- and hormone-induced cAMP oscillations in alpha- and beta-cells within intact pancreatic islets. Diabetes 60: 1535–1543, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vaeth M, Schliesser U, Müller G, Reissig S, Satoh K, Tuettenberg A, Jonuleit H, Waisman A, Müller MR, Serfling E, Sawitzki BS, Berberich-Siebelt F. Dependence on nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT) levels discriminates conventional T cells from Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 16258–16263, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vikram A, Jena G. S961, an insulin receptor antagonist causes hyperinsulinemia, insulin-resistance and depletion of energy stores in rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 398: 260–265, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vollert S, Kaessner N, Heuser A, Hanauer G, Dieckmann A, Knaack D, Kley HP, Beume R, Weiss-Haljiti C. The glucose-lowering effects of the PDE4 inhibitors roflumilast and roflumilast-N-oxide in db/db mice. Diabetologia 55: 2779–2788, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu E, Kumar M, Zhang Y, Ju W, Obata T, Zhang N, Liu S, Wendt A, Deng S, Ebina Y, Wheeler MB, Braun M, Wang Q. Intra-islet insulin suppresses glucagon release via GABA-GABAA receptor system. Cell Metab 3: 47–58, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yue JT, Burdett E, Coy DH, Giacca A, Efendic S, Vranic M. Somatostatin receptor type 2 antagonism improves glucagon and corticosterone counterregulatory responses to hypoglycemia in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Diabetes 61: 197–207, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang Q, Ramracheya R, Lahmann C, Tarasov A, Bengtsson M, Braha O, Braun M, Brereton M, Collins S, Galvanovskis J, Gonzalez A, Groschner LN, Rorsman NJ, Salehi A, Travers ME, Walker JN, Gloyn AL, Gribble F, Johnson PR, Reimann F, Ashcroft FM, Rorsman P. Role Of KATP channels in glucose-regulated glucagon secretion and impaired counterregulation in type 2 diabetes. Cell Metab 18: 871–882, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zmuda-Trzebiatowska E, Oknianska A, Manganiello V, Degerman E. Role Of PDE3B in insulin-induced glucose uptake, GLUT-4 translocation and lipogenesis in primary rat adipocytes. Cell Signal 18: 382–390, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]