Abstract

In a previous study (Kelleher AR, Kimball SR, Dennis MD, Schilder RJ, and Jefferson LS. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 304: E229–236, 2013.), we observed a rapid (i.e., 1–3 days) immobilization-induced repression of mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) signaling in hindlimb skeletal muscle of young (2-mo-old) rats that was associated with elevated expression of regulated in development and DNA-damage response (REDD) 1 and REDD2. The present study extends that observation to include an assessment of those parameters in soleus muscle of the immobilized hindlimb of various-aged rats as well as in response to remobilization. Male Sprague-Dawley rats aged 2, 9, and 18 mo were subjected to unilateral hindlimb immobilization for 7 days, whereas one group of the 9-mo-old animals underwent 7 days of remobilization. Soleus muscle mass-to-body mass ratio declined with age, with the loss of muscle mass following hindlimb immobilization being inversely proportional to age. Compared with 2-mo-old rats, the older rats exhibited reduced mTORC1 signaling in the nonimmobilized limb in association with elevated REDD2, but not REDD1, mRNA expression. In the 2-mo-old rats, 7 days of hindlimb immobilization attenuated mTORC1 signaling and induced REDD2, but not REDD1, mRNA expression. In contrast, hindlimb immobilization did not further attenuate the age-related reduction in mTORC1 signaling nor further enhance the age-related induction of REDD2 mRNA expression in 9- and 18-mo-old rats. Across ages, REDD1 mRNA was not impacted by immobilization. Finally, remobilization elevated mTORC1 signaling and lowered REDD2 mRNA expression, with no impact on REDD1 gene expression. In conclusion, changes in mTORC1 signaling associated with aging, immobilization, and remobilization were inversely proportional to alterations in REDD2 mRNA expression.

Keywords: anabolic resistance, casting, atrophy, DDIT4l, disuse

loss of skeletal muscle mass and function in the elderly leads to increased risk of falls and fractures, physical frailty, and increased morbidity and mortality (11, 39, 53). A period of inactivity (e.g., limb immobilization, bed rest, etc.) worsens the problem, since it leads to acute skeletal muscle atrophy (52). Both age- and inactivity-induced muscle atrophy are thought to be in large part a consequence of the development of resistance to nutrient (particularly amino acids)-induced stimulation of muscle protein synthesis (42, 49). In young adult humans (e.g., ∼25 yr old), muscle protein synthesis is stimulated in response to consumption of relatively small quantities (e.g., 7–10 g) of essential amino acids, whereas in older adults (e.g., ∼65 yr old) a comparable amount of amino acids is ineffective (31, 32). However, ingesting larger quantities of amino acids (e.g., 25–30 g) effectively stimulates muscle protein synthesis in both young and older individuals (55, 56). Notably, the responsiveness of muscle protein synthesis in the elderly to small quantities of essential amino acids can be overcome by increasing the leucine content of the mixture (21, 32). Similar results have been reported for studies in rats in which the age-related resistance of skeletal muscle protein synthesis to stimulation by a protein diet can be overcome by supplementation with leucine (14). Combined, the results from both human and rat studies suggest that the age-related loss of muscle responsiveness to amino acids is largely due to impaired leucine sensitivity.

The anabolic effects of amino acids in muscle are due in large part to mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1)-mediated stimulation of protein synthesis (for review, see Ref. 24). Upon activation by amino acids, hormones, or exercise, mTORC1 phosphorylates protein substrates at specific residues, including p70 ribosomal protein S6 kinase 1 (p70S6K1) on Thr389 and uncoordinated-51 like autophagy activating kinase 1 (ULK1) on Ser757, which promotes mRNA translation and represses autophagy, respectively (23, 34, 44). The key role played by mTORC1 in determining muscle size is evident in studies in which conditional deletion of mTORC1 components (e.g., raptor or mTOR) leads to development of a muscle dystrophy phenotype with reduced muscle weight and fiber cross-sectional area (7, 50). In a previous study, we observed an immobilization-induced attenuation of mTORC1 signaling that was resistant to a nutrient-induced stimulation (33). We also found that immobilization for 3 days led to induction in the expression of mRNAs for two mTORC1 repressors, regulated in development and DNA-damage response (REDD) 1 and REDD2, encoded by the DDIT4 and DDIT4L genes, respectively. Consequently, the question arises as to the role of REDD1 and REDD2 in contributing to the loss of skeletal muscle that occurs in response to aging and remobilization.

In the present study, we tested the hypothesis that REDD1 and/or REDD2 mRNA expression is elevated in muscle from older compared with young rats in association with attenuated mTORC1 signaling and that the immobilization-induced stimulation of REDD1 and/or REDD2 expression is exacerbated in older compared with young rats. We also tested the hypothesis that remobilization reverses the immobilization-induced induction of REDD1 and/or REDD2 expression in conjunction with restoration of mTORC1 signaling.

METHODS

Animals.

Male Sprague-Dawley rats of age 2, 9, and 18 mo (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MD; and Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN) were housed in wire cages in a temperature (25°C)- and light-controlled environment. Rats were provided rodent chow (AIN-93M; Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ) and water ad libitum. Before hindlimb immobilization, rats were adapted to a reversed 12:12-h light-dark cycle (lights off at 0700) for 1 wk. Animal facilities and experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of The Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine.

Experimental design.

Rats were anesthetized by isoflurane inhalation (2.5%) and subjected to unilateral hindlimb immobilization by casting as described previously (33). Hindlimbs were immobilized for 7 days before removal of the soleus muscle for subsequent analysis. An additional group of 9-mo-old rats was subjected to unilateral hindlimb immobilization for 7 days, and, following removal of the cast, they were allowed to remobilize for 7 days. Before the day of tissue harvest, all rats were fasted overnight (18 h) but allowed free access to water. On tissue harvest days, rats were individually caged and provided with similar amounts of rodent chow (AIN-93M) for 10 min. One rat did not eat and was excluded from the study. The remaining rats on average consumed 3.2 ± 0.2 g of food, and there was no significant difference in food consumption among the groups as assessed by ANOVA with Holm-Sidak correction for multiple comparisons. Thus, all rats were in a fed state at the time of the analysis. The animals were subsequently anesthetized using isoflurane and remained anesthetized for the remainder of the experiment. The soleus muscle was removed from the immobilized and the contralateral nonimmobilized (control) hindlimb 45 min after the start of chow feeding. This time point was selected based on previous studies showing that the peak response of mTORC1 signaling in skeletal muscle to a nutrient-induced stimulus occurs between 45 and 60 min (4). Muscle from the nonimmobilized hindlimb was used as a control based on the observation in our previous study (33) that nutrient-induced mTORC1 signaling responded identically in the soleus of the nonimmobilized hindlimb of an immobilized rat compared with the soleus of a rat not subjected to immobilization.

Sample preparation and immunoblot procedure.

The soleus muscle was chosen for analysis in the present study so that the results could be compared with those in our previous study investigating the effect of unilateral hindlimb immobilization on mTORC1 signaling in young rats (33). Soleus muscle was dissected from each hindlimb, weighed, and processed for analysis of mRNA expression and phosphorylation state of key proteins in the mTORC1 signaling pathway as described previously (33). For immunoblot analysis, polyvinylidene difluoride membranes were incubated with primary antibodies recognizing proteins phosphorylated on specific residues, including p70S6K1 Thr389, ULK1 Ser757, or Akt Ser473, all of which were from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). Alternatively, blots were probed with antibodies from Bethyl Laboratories (Montgomery, TX) against ULK1 or Akt (Cell Signaling Technology) or p70S6K1. Blots were developed using a FluorChem M Multifluor System (ProteinSimple, San Jose, CA) and analyzed using AlphaView (ProteinSimple) and Genetools (Syngene, Cambridge, MA) software.

Measurement of mRNA expression.

RNA was isolated from soleus muscle harvested 45 min after the start of chow feeding using the TRIzol method (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) and prepared for real-time polymerase chain reaction as previously described (33). Primers were purchased from Applied Biosystems, including Ddit4 (REDD1) (assay ID: Rn01433735_g1), Ddit4l (REDD2) (Rn00589659_g1), Trim63 (MuRF1) (Rn00590197_m1), Fbxo32 (MAFbx) (Rn00591730_m1), and Tbp (TATA-binding protein) (Rn01455646_m1). Tbp mRNA expression was compared against the expression of other common housekeeping genes, including β-actin, Hprt1, Polr2a, and Rpl32. Tbp mRNA expression was used as an internal control, since its expression did not change substantially with aging or in response to 7 days of immobilization or remobilization.

Statistical analysis.

Results from individual groups are presented as means ± SE. Outliers were determined using Grubb's test (α-level 0.05) and excluded from further analysis. Data for the immobilized rats was analyzed by two-way ANOVA with Newman-Keuls correction for multiple comparisons with age and immobilization status as variables. The effects of remobilization were assessed by comparing data from the 9-mo-old immobilized rats with that obtained from rats in the remobilization group by ANOVA with Newman-Keuls correction for multiple comparisons. Nonlinear regression (curve fit) analysis was used to assess the relative relationship between p70S6K1 phosphorylation on Thr389 and REDD2 mRNA expression for all samples. All comparisons were performed using GraphPad Prism 6 software. Differences between groups were considered significant at P ≤ 0.05.

RESULTS

Effect of age and remobilization on immobilization-induced loss of muscle mass.

As shown in Table 1, the soleus muscle mass-to-body mass ratio declined with age, being significantly lower (P < 0.05) in 18-mo-old rats compared with both 2- and 9-mo-old rats. In response to 7 days of hindlimb immobilization, muscle mass-to-body mass ratio was reduced in rats from all age groups. Notably, the magnitude of the loss of muscle mass following hindlimb immobilization was inversely proportional to age, where the muscle mass-to-body mass ratio was reduced 40, 15, and 8% in the soleus muscle from the immobilized hindlimb of 2-, 9-, and 18-mo-old rats, respectively, when compared with the soleus muscle from the contralateral nonimmobilized hindlimb (referred to hereafter as the control hindlimb). No difference in muscle mass-to-body mass ratio was observed between the soleus muscle from the control hindlimb of 9-mo-old immobilized and remobilized rats. Following 7 days of remobilization, muscle mass-to-body mass ratio was further reduced (P < 0.05) in the soleus muscle from the remobilized hindlimb compared with either the immobilized or the control hindlimb of 9-mo-old rats. Similar results were obtained for the gastrocnemius and plantaris muscles (Table 1).

Table 1.

Young rats are more susceptible to hindlimb immobilization-induced loss of muscle mass than older rats

| Muscle and Age | Muscle Mass, g |

Muscle Mass/Body Mass (×10,000) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immob or recov limb | Control limb | Immob or recov limb | Control limb | |

| Soleus | ||||

| 2 mo | 0.098 ± 0.007*#+ | 0.163 ± 0.007# | 3.13 ± 0.19*# | 5.04 ± 0.18#+ |

| 9 mo | 0.174 ± 0.002 | 0.204 ± 0.008 | 4.18 ± 0.19*+ | 4.57 ± 0.16+ |

| 9 mo (recov) | 0.143 ± 0.010*# | 0.186 ± 0.009 | 3.45 ± 0.18* | 4.48 ± 0.91 |

| 18 mo | 0.188 ± 0.004 | 0.202 ± 0.010 | 3.29 ± 0.20# | 3.63 ± 0.19# |

| Gastrocnemius | ||||

| 2 mo | 1.196 ± 0.044*#+ | 1.809 ± 0.027#+ | 37.3 ± 1.32*# | 56.5 ± 5.07+ |

| 9 mo | 2.213 ± 0.069* | 2.603 ± 0.097 | 49.4 ± 1.42*+ | 55.5 ± 2.03+ |

| 9 mo (recov) | 1.466 ± 0.073*# | 2.287 ± 0.075 | 35.4 ± 1.13*# | 55.5 ± 1.93 |

| 18 mo | 2.106 ± 0.091* | 2.543 ± 0.093 | 39.3 ± 1.33*# | 47.5 ± 1.46# |

| Plantaris | ||||

| 2 mo | 0.237 ± 0.006*#+ | 0.344 ± 0.010#+ | 7.42 ± 2.78*#+ | 10.7 ± 0.30 |

| 9 mo | 0.421 ± 0.016* | 0.501 ± 0.024+ | 9.23 ± 0.33* | 11.0 ± 0.45 |

| 9 mo (recov) | 0.310 ± 0.023*# | 0.475 ± 0.008 | 7.49 ± 0.45*# | 12.0 ± 0.40 |

| 18 mo | 0.459 ± 0.017* | 0.557 ± 0.020 | 8.56 ± 0.28* | 10.4 ± 0.46 |

Values are means ± SE. Rats 2, 9, and 18 mo of age had one hindlimb immobilized (Immob) for 7 days, and an additional group of 9-mo-old animals had their casts removed after 7 days and were allowed to remobilize for an additional 7 days (recov). Body weights were 320.5 ± 5.3, 456.5 ± 4.4, and 537.5 ± 21.4 for 2-, 9-, and 19-mo-old rats, respectively, and 414 ± 16.6 for 9 mo-old rats after recovery for 7 days.

P < 0.05 compared with control limb;

P < 0.05 compared with equivalent limb in 9-mo-old rats; and

P < 0.05 compared with equivalent limb in 18-mo-old rats.

Effect of age, immobilization, and remobilization on mTORC1 signaling.

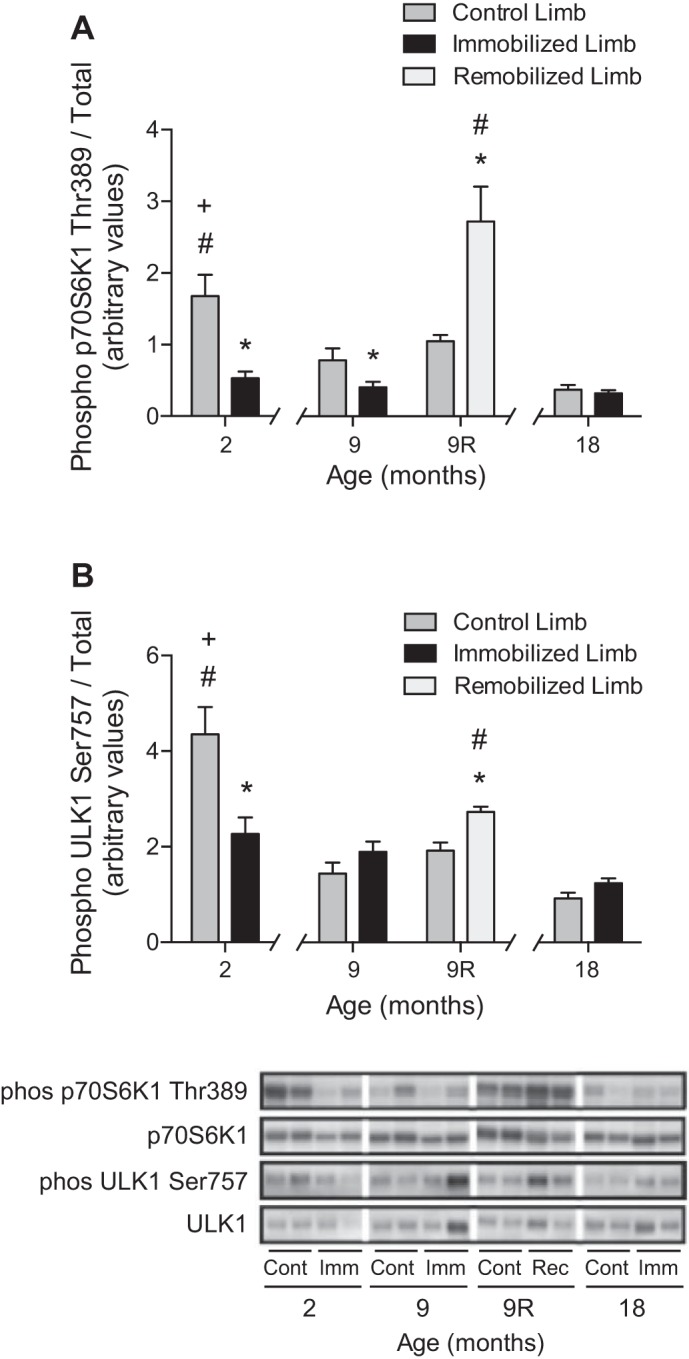

To gain an understanding of the potential molecular events responsible for age- and immobilization-induced skeletal muscle atrophy, rats were provided with a nutrient stimulus to produce an anabolic response that was assessed by analysis of the phosphorylation state of residues on two proteins known to be direct targets of mTORC1, i.e., p70S6K1 Thr389 and ULK1 Ser757. The analysis demonstrated that aging was associated with a 53 and 78% attenuation of the nutrient-induced stimulation of p70S6K1 phosphorylation on Thr389 in the soleus muscle from the control hindlimb of 9- and 18-mo-old rats, respectively, relative to the soleus muscle from the control hindlimb of 2-mo-old rats (Fig. 1). In response to 7 days of hindlimb immobilization, the nutrient-induced stimulation of phosphorylation of p70S6K1 on Thr389 was reduced 68 and 48% in the soleus muscle from the immobilized hindlimb relative to the control hindlimb of 2- and 9-mo-old rats, respectively, whereas it was unchanged from the control value in 18-mo-old rats. Nutrient-induced stimulation of ULK1 phosphorylation on Ser757 also declined with age, and, in response to immobilization, it was reduced 48% relative to the control hindlimb of 2-mo-old rats. No difference was observed in ULK1 phosphorylation state between hindlimbs of 9- or 18-mo-old rats. Following 7 days of remobilization, mTORC1 signaling was augmented in the soleus muscle from the remobilized limb relative to the control hindlimb, i.e., phosphorylation of p70S6K1 on Thr389 and ULK1 on Ser757 was elevated 160 and 42%, respectively, in the soleus muscle from the remobilized hindlimb.

Fig. 1.

Nutrient-induced activation of mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) signaling declines dramatically during aging, and in older animals the pathway is not responsive to immobilization but is augmented following remobilization. Rats 2, 9, and 18 mo of age had one hindlimb immobilized for 7 days, and an additional group of 9-mo-old animals had their casts removed after 7 days and were allowed to remobilize for an additional 7 days (9R). Relative phosphorylation of p70 ribosomal protein S6 kinase 1 (p70S6K1) on Thr389 (A) and uncoordinated-51 like autophagy activating kinase 1 (ULK1) on Ser757 (B) in the soleus muscle was assessed by protein immunoblot analysis. Bars represent the mean phospho-to-total protein ratio in the soleus muscle from control (dark gray), immobilized (black), and remobilized (light gray) hindlimbs. No differences were observed in total p70S6K1 or ULK1 protein expression. Samples were run on the same blot, but not in contiguous lanes. Noncontiguous lanes are denoted by a white line. For each condition, samples from two animals are shown. Data are means ± SE, n = 5–6 rats/group. *P < 0.05 compared with control limb. #P < 0.05 compared with equivalent limb in 9-mo-old rat. +P < 0.05 compared with equivalent limb in 18-mo-old rat.

Effect of age, immobilization, and remobilization on Akt activation.

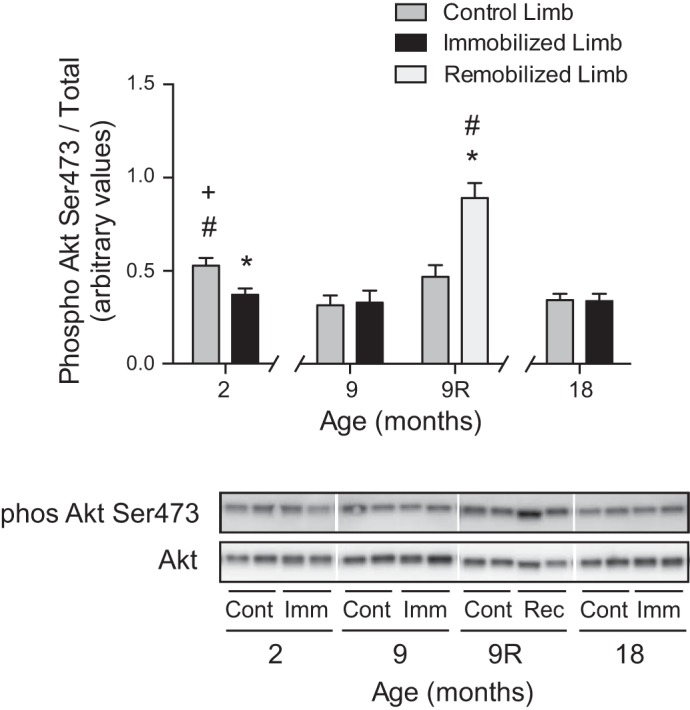

As a biomarker of an upstream signaling input to mTORC1, phosphorylation of Akt on Ser473 was assessed as an index of the activation state of the kinase. The assessment demonstrated that aging was associated with attenuation of the nutrient-induced activation of Akt in soleus muscle from the control hindlimb of 9- and 18-mo-old rats relative to the soleus muscle from the control hindlimb of 2-mo-old rats (Fig. 2). In response to 7 days of hindlimb immobilization, the nutrient-induced phosphorylation of Akt on Ser473 was reduced 30% in the soleus muscle from the immobilized hindlimb relative to the soleus from the control hindlimb of 2-mo-old rats. No difference in nutrient-induced phosphorylation of Akt on Ser473 was observed between the soleus muscle from the immobilized and the control hindlimb of 9- and 18-mo-old rats. Following 7 days of remobilization, phosphorylation of Akt on Ser473 was augmented 90% in the soleus muscle from the remobilized limb relative to the soleus muscle from the control hindlimb.

Fig. 2.

Feeding-induced activation of Akt is blunted with age and hindlimb immobilization in skeletal muscle from young vs. older rats and is augmented following remobilization. Rats 2, 9, and 18 mo of age had one hindlimb immobilized for 7 days, and an additional group of 9-mo-old animals had their casts removed after 7 days and were allowed to remobilize for an additional 7 days. Relative phosphorylation of Akt on Ser473 in the soleus muscle was assessed by protein immunoblot analysis. Bars represent the mean phospho-to-total protein ratio in the soleus muscle from control (dark gray), immobilized (black), and remobilized (light gray) hindlimbs. No differences were observed in total Akt protein expression. Samples were run on the same blot, but not in contiguous lanes. Noncontiguous lanes are denoted by a white line. For each condition, samples from two animals are shown. Data are means ± SE, n = 5–6 rats/group. *P < 0.05 compared with control limb. #P < 0.05 compared with equivalent limb in 9-mo-old rat. +P < 0.05 compared with equivalent limb in 18-mo-old rat.

Effect of age, immobilization, and remobilization on REDD1 and REDD2 mRNA expression.

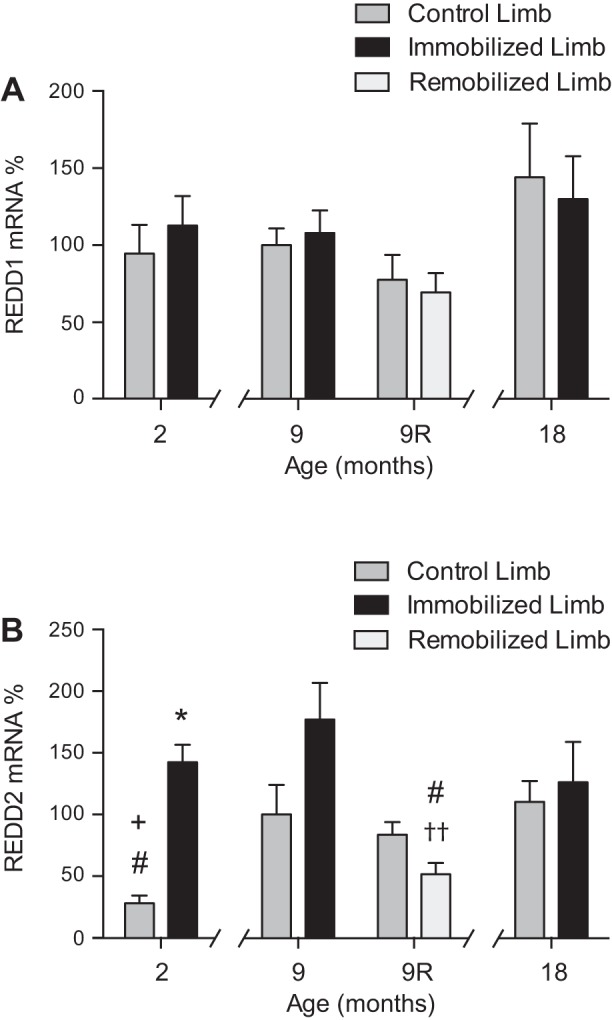

To gain an understanding of the mechanism(s) responsible for the observed responses of mTORC1 signaling to aging, hindlimb immobilization, and remobilization, the mRNA expression for two repressors of the pathway, i.e., REDD1 and REDD2, was assessed. In contrast to our earlier study showing an increase in REDD1 mRNA expression following 1, 2, or 3 days of immobilization (33), its expression was unchanged from the control value following 7 days of immobilization (Fig. 3A). Moreover, no change in REDD1 mRNA expression was observed in response to aging or remobilization. In contrast, aging was associated with increased expression of REDD2 mRNA, i.e., its expression was increased ∼250 and 300% in the soleus muscle from the control hindlimb of 9- and 18-mo-old rats, respectively, relative to the soleus muscle from the control hindlimb of 2-mo-old rats (Fig. 3B). In response to 7 days of hindlimb immobilization, REDD2 mRNA expression was increased >400% in the soleus muscle from the immobilized hindlimb relative to the soleus muscle from the control hindlimb of 2-mo-old rats. In 9-mo-old rats, REDD2 mRNA expression in the soleus muscle from the immobilized hindlimb relative to the soleus muscle from the control hindlimb was further increased by 77% above the aging-induced response; however, this trend did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.16). Moreover, in 18-mo-old rats, immobilization did not enhance REDD2 mRNA expression above the aging-induced response. Following 7 days of remobilization, REDD2 mRNA expression was repressed 38% in the soleus muscle from the remobilized limb relative to the soleus muscle from the control hindlimb and was significantly lower than the REDD2 mRNA expression in the soleus muscle from the immobilized hindlimb of 9-mo-old rats.

Fig. 3.

Regulated in development and DNA-damage response (REDD) 2, but not REDD1, mRNA expression increases with age and becomes unresponsive to immobilization, but is repressed following remobilization. REDD1 and REDD2 mRNA expression in the soleus muscle was assessed by Taqman gene expression assay. Rats 2, 9, and 18 mo of age had one hindlimb immobilized for 7 days, and an additional group of 9-mo-old animals had their casts removed after 7 days and were allowed to remobilize for an additional 7 days. Bars represent the mean REDD1 mRNA (A)- or REDD2 mRNA (B)-to-TATA-binding protein (Tbp) mRNA ratio in the soleus muscle from control (dark gray), immobilized (black), and remobilized (light gray) hindlimbs expressed as a percentage of the same ratio in the soleus muscle from nonimmobilized hindlimbs of 9-mo-old rats. Tbp gene expression was verified against three common loading controls as a reliable housekeeping gene. Data are means ± SE, n = 4–6 rats/group. *P < 0.05 compared with control limb. #P < 0.05 compared with equivalent limb in 9-mo-old rat. +P < 0.05 compared with equivalent limb in 18-mo-old rat. ††P = 0.08 compared with control limb by paired t-test.

Relationship between p70S6K1 Thr389 phosphorylation and REDD2 mRNA expression.

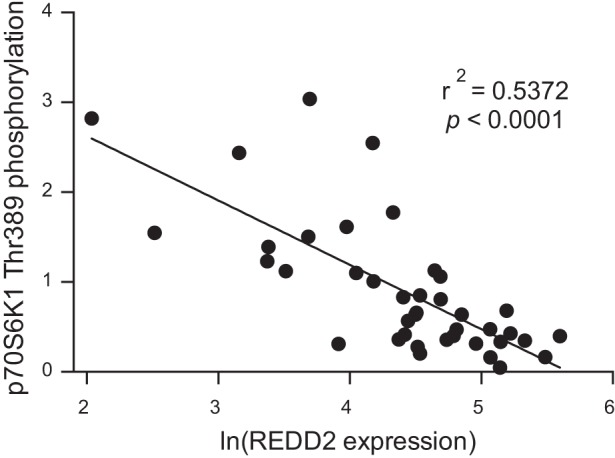

Across age groups and conditions, there appeared to be an association between mTORC1 signaling and REDD2 mRNA expression in the soleus muscle from rat hindlimbs, i.e., the phosphorylation of p70S6K1 on Thr389 and ULK1 on Ser757 was inversely proportional to REDD2 mRNA expression. A scatter plot with the natural logarithm (ln) of REDD2 mRNA expression and the phosphorylation of p70S6K1 on Thr389 plotted on the x- and y-axes, respectively, revealed a linear relationship between these two variables. As shown in Fig. 4, low REDD2 mRNA expression was associated with high phosphorylation of p70S6K1 on Thr389, and increases in REDD2 mRNA expression were associated with reductions in phosphorylation of p70S6K1 on Thr389. Fitting a linear regression to these points revealed a negative correlation (r2 = 0.53) between REDD2 mRNA expression and phosphorylation of p70S6K1 on Thr389 (P < 0.0001). Similarly, ln(REDD2 mRNA expression) and ULK1 phosphorylation exhibited a negative correlation (r2 = 0.26; P = 0.001) by linear regression.

Fig. 4.

REDD2 mRNA expression is inversely proportional to phosphorylation of p70S6K1 on Thr389 in rat soleus muscle. All data points represent an individual rat soleus muscle from 2-, 9-, and 18-mo-old rats that had one hindlimb immobilized for 7 days and an additional group of 9-mo-old animals that had their casts removed after 7 days and were allowed to remobilize for an additional 7 days. Data for REDD2 mRNA expression and relative p70S6K1 phosphorylation on Thr389 were taken from Figs. 3B and 1A, respectively. A negative correlation (r2 = 0.5372) between REDD2 mRNA expression and phosphorylation of p70S6K1 on Thr389 (P < 0.0001) was established by fitting a linear regression to these points.

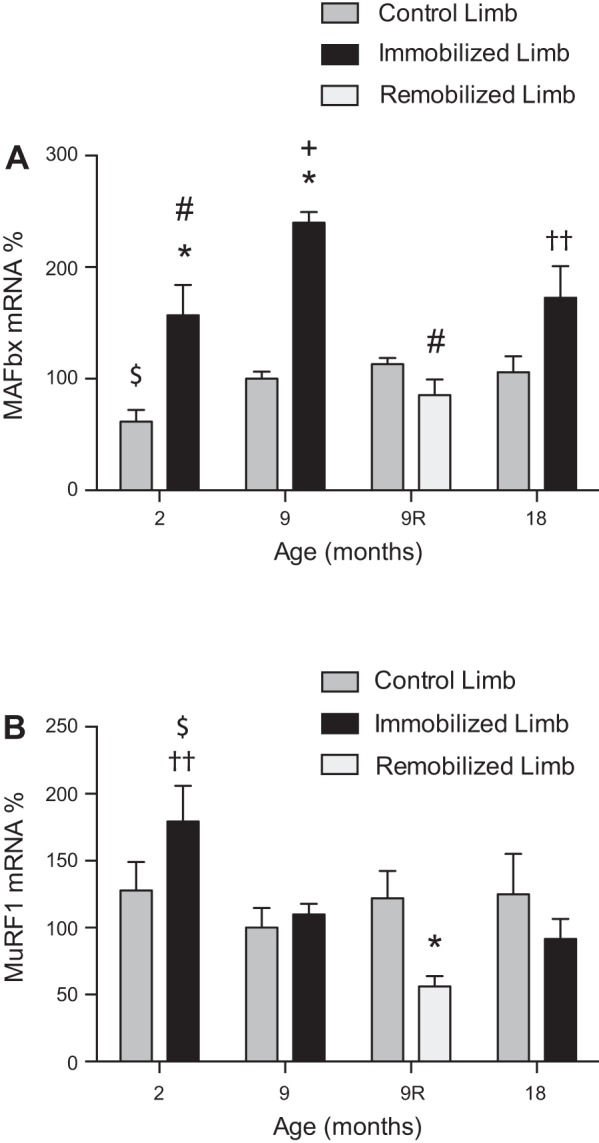

Effect of age, immobilization, and remobilization on atrogene mRNA expression.

To determine whether other biomarkers of muscle atrophy change coordinately with REDD2, the mRNA expression of the E3 ubiquitin ligases, MAFbx and MuRF1 (also known as “atrogenes”; see Ref. 8), was assessed. The mRNA expression of MAFbx (Fig. 5A) was elevated 63 and 47% in the soleus muscle of the control hindlimb of 9- and 18-mo-old rats, respectively, compared with the soleus muscle of the control hindlimb of 2-mo-old rats, although the difference was not statistically significant by ANOVA. Moreover, after 7 days of immobilization, MAFbx mRNA expression was higher in soleus muscle of the immobilized compared with the control hindlimb in each age group, although the difference at 18 mo was only significant by t-test. Aging had no significant effect on the mRNA expression of MuRF1 (Fig. 5B). Interestingly, although MuRF1 was elevated in the soleus muscle of the immobilized hindlimb of 2-mo-old rats as assessed by t-test, it was not elevated in response to immobilization in 9- and 18-mo-old rats. In response to 7 days of remobilization, MAFbx expression was lower in soleus muscle of the remobilized hindlimb compared with the soleus muscle of the immobilized hindlimb of 9-mo-old rats. However, MAFbx mRNA expression was not statistically different between the soleus muscle of the remobilized and the nonimmobilized hindlimb of the same rat. In contrast, MuRF1 mRNA expression was lower in the soleus muscle of the remobilized hindlimb compared with the control hindlimb of 9-mo-old rats.

Fig. 5.

MAFbx mRNA expression increases with age and 7 days of immobilization, whereas MuRF1 mRNA expression increases with immobilization only in 2-mo-old animals and decreases in response to remobilization. MAFbx and MuRF1 mRNA expression in the soleus muscle was assessed by Taqman gene expression assay. Rats 2, 9, and 18 mo of age had one hindlimb immobilized for 7 days, and an additional group of 9-mo-old animals had their casts removed after 7 days and were allowed to remobilize for an additional 7 days. Bars represent the mean MAFbx mRNA (A)- or MuRF1 mRNA (B)-to-Tbp mRNA ratio in the soleus muscle from control (dark gray), immobilized (black), and remobilized (light gray) hindlimbs expressed as a percentage of the same ratio in the soleus muscle from control hindlimbs of 9-mo-old rats. Tbp gene expression was verified against three common loading controls as a reliable housekeeping gene. Data are means ± SE, n = 4–6 rats/group. *P < 0.05 compared with control limb. #P < 0.05 compared with equivalent limb in 9-mo-old rat. +P < 0.05 compared with equivalent limb in 18-mo-old rat. ††P < 0.05 compared with control limb by unpaired t-test. $P < 0.05 vs. equivalent limb in 9- or 18-mo-old rat.

DISCUSSION

In both animals (3) and humans (15), nutrients induce stimulation of protein synthesis through activation of the mTORC1 signaling pathway. In agreement with the impaired responsiveness of muscle protein synthesis to stimulation by nutrients, the sensitivity of mTORC1 signaling to activation by amino acids is also attenuated in muscle from older individuals compared with young adults (26). In the present study, a similar phenomenon was observed in rats, i.e., aging was associated with a proportional reduction in nutrient-induced activation of mTORC1 signaling. Notably, the decline in sensitivity of mTORC1 to nutrient-induced activation was inversely correlated with changes in expression of REDD2, which, in addition to REDD1, is a dominant repressor of the pathway. Many studies have focused on the role of REDD1 and/or REDD2 in repressing mTORC1 signaling under conditions of cell stress (13, 19, 41), with many fewer assessing their role under physiological conditions. However, recent reports have demonstrated an inverse correlation between changes in mTORC1 signaling and REDD1 and/or REDD2 expression in skeletal muscle in response to fasting and refeeding (43) as well as after a bout of resistance exercise (16, 17, 25). The present study extends these observations to show that elevated REDD2 mRNA expression in 9- and 18-mo-old rats is associated with an attenuation of nutrient-induced activation of mTORC1 signaling. The mechanism through which aging acts to induce REDD2 expression is unknown. However, it is notable that many of the stressors that have been shown to enhance REDD1 and/or REDD2 gene transcription, e.g., endoplasmic reticulum stress (58) or conditions that cause DNA damage (37) or increase production of reactive oxygen species (20), have been reported to be elevated in muscle from older compared with younger individuals (6, 38, 42, 47). Thus, it is tempting to speculate that one, or more, of these stressors is responsible for mediating the induction of REDD2 mRNA expression observed in the present study. It should be noted that, in a previous study in humans (17), no difference in expression of either REDD1 or REDD2 mRNA was observed in skeletal muscle from young (29 ± 2) compared with older (70 ± 2) individuals. However, the apparent discrepancy between the results of that study and the present one is likely due to the age of the individuals assessed. In the present study, a significant increase in REDD2 mRNA in soleus muscle from the control limb was observed between 2 and 9 mo of age, with a further slight nonsignificant increase occurring between 9 and 18 mo. Thus, much of the increase occurred during the transition from young rapidly growing to middle-aged rats, thus emphasizing the importance of the age of the subject being studied.

Previously, we reported a rapid induction of both REDD1 and REDD2 mRNA expression in soleus muscle following hindlimb immobilization of 1–3 days duration compared with the values observed in either the contralateral nonimmobilized limb or the limb of a control 2-mo-old rat (33). In the present study, following 7 days of hindlimb immobilization, REDD1 mRNA expression was the same in the immobilized compared with the control limb, whereas REDD2 mRNA expression was elevated. The simplest explanation for the discrepancy is that REDD1 and REDD2 mRNAs are initially (i.e., 1–3 days) induced in response to immobilization. At later times REDD1 mRNA returns to control values, whereas REDD2 mRNA expression is maintained. Thus, the rapid and transient induction of REDD1 mRNA expression observed in the prior study may have resulted from the stress of the immobilization procedure. In contrast, based on the results presented here, REDD2 induction would seem to be the more relevant response to immobilization. Such a possibility is consistent with the finding that REDD2 mRNA expression is enriched in skeletal muscle compared with other tissues (45). It should be noted that the data presented herein are for mRNA and not protein expression for REDD2. Presently, assessing changes in REDD2 protein expression is not feasible due to the lack of anti-REDD2 antibodies that recognize the rat protein.

Another key result of the present study is the observation that the enhanced nutrient-induced activation of mTORC1 signaling that occurs in response to remobilization is associated with reduction in REDD2 mRNA expression. This result agrees with earlier ones that have also observed an enhancement of mTORC1 signaling in skeletal muscle following 1–7 days of remobilization (10, 35, 36, 46). Repression of REDD2 mRNA expression during remobilization would provide a mechanism for relieving the resistance to nutrient-induced activation of mTORC1 signaling following immobilization. Notably, despite the activation of mTORC1 signaling, muscle mass continued to fall during the period of remobilization. A similar phenomenon has been previously reported (35, 40). The molecular basis for the delayed recovery of muscle mass with remobilization is unknown. One potential mechanism could be linked to myonuclear apoptosis that occurs during immobilization and is still prevalent during reloading (27, 51). It is also tempting to speculate that it may be related to a reduction in RNA content, and thus ribosome abundance. In young growing animals, ribosome number is elevated to allow for higher rates of protein synthesis after an anabolic stimulus, whereas fewer ribosomes would be needed to maintain the relatively static muscle mass in older animals. Thus, an increase in ribosome number in the older animals may be required for muscle hypertrophy following remobilization. Notably, ribosome biogenesis, which is under the control of mTORC1 signaling (30), is reduced during hindlimb suspension and immobilization (5) and enhanced during reloading following hindlimb suspension (28). Due to the relatively slow turnover of ribosomes, it is not surprising to observe a delay in the response of skeletal muscle protein synthesis and growth (i.e., mass) to immobilization and/or remobilization in muscle from older animals.

Models of both aging- and inactivity-induced muscle atrophy are associated with insulin resistance in skeletal muscle (9, 11, 48, 57, 59, 60). The alterations in the nutrient-induced stimulation of phosphorylation of Akt on Ser473 observed in the present study in response to aging and hindlimb immobilization and remobilization are in agreement with other reports (10, 29, 46, 60). It remains to be determined whether these changes in phosphorylation of Akt on Ser473 are linked with changes in REDD2 mRNA expression. Thus, future studies are needed to determine the contributions of induced REDD2 mRNA expression vs. attenuated Akt phosphorylation on mTORC1 signaling during aging, hindlimb immobilization, and remobilization.

Increased expression of the atrogenes, MAFbx and MuRF1, is considered to be an early marker of disuse atrophy (1, 35, 54) because expression of the mRNAs encoding the proteins is rapidly induced after limb immobilization in association with loss of muscle mass (8, 22). The results of the present study showing that, in 2-mo-old rats, expression of both MAFbx and MuRF1 mRNA is upregulated after 7 days of hindlimb immobilization is in agreement with these previous reports. However, unlike MAFbx mRNA that exhibited increased abundance in older (i.e., 2- compared with 9-mo-old) rats, MuRF1 mRNA expression in the present study was unaffected by age. This finding corroborates a previous report that MuRF1 mRNA expression was increased in muscle from older compared with younger rats (12) but disagrees with other studies reporting that MuRF1 mRNA expression is either unchanged (2) or decreased (18) during aging. Conflicting findings regarding the effect of age on MAFbx mRNA expression have also been reported, with different studies showing increased (12), decreased (18), or no change (2) in older compared with younger animals. The reason for the discrepant findings among studies is unclear but is likely due to differences in the muscle being examined, the age of the animals, or species.

In conclusion, nutrient-induced activation of mTORC1 signaling was enhanced and REDD2 mRNA expression was reduced in skeletal muscle from young compared with older rats. Moreover, mTORC1 signaling was enhanced by 7 days of remobilization in association with reduced REDD2 mRNA expression. No differences in REDD1 mRNA expression were observed in skeletal muscle due to aging, hindlimb immobilization, or remobilization. Therefore, REDD2 expression appears to play a prominent role in the regulation of mTORC1 signaling in skeletal muscle during aging, and hindlimb immobilization and remobilization, and consequently in modulating skeletal muscle mass.

GRANTS

The work was supported in part by Abbott Nutrition (S. R. Kimball) and a grant from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (DK-15658; L. S. Jefferson).

DISCLOSURES

SLP is an employee of Abbott Nutrition R&D. Otherwise, the authors declare no conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: A.R.K., S.L.P., L.S.J., and S.R.K. conception and design of research; A.R.K. performed experiments; A.R.K. analyzed data; A.R.K., L.S.J., and S.R.K. interpreted results of experiments; A.R.K. prepared figures; A.R.K. drafted manuscript; A.R.K., S.L.P., L.S.J., and S.R.K. edited and revised manuscript; A.R.K., S.L.P., L.S.J., and S.R.K. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Holly Lacko, Sharon Rannels, Lydia Kutzler, and Dr. Bradley Gordon for assistance in performing the studies and Dr. Arthur Berg (The Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine) for help in statistical analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abadi A, Glover EI, Isfort RJ, Raha S, Safdar A, Yasuda N, Kaczor JJ, Melov S, Hubbard A, Qu X, Phillips SM, Tarnopolsky M. Limb immobilization induces a coordinate down-regulation of mitochondrial and other metabolic pathways in men and women. PLoS One 4: e6518, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altun M, Besche HC, Overkleeft HS, Piccirillo R, Edelmann MJ, Kessler BM, Goldberg AL, Ulfhake B. Muscle wasting in aged, sarcopenic rats is associated with enhanced activity of the ubiquitin proteasome pathway. J Biol Chem 285: 39597–39608, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anthony JC, Anthony TG, Kimball SR, Vary TC, Jefferson LS. Orally administered leucine stimulates protein synthesis in skeletal muscle of postabsorptive rats in association with increased eIF4F formation. J Nutr 130: 139–145, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anthony JC, Lang CH, Crozier SJ, Anthony TG, MacLean DA, Kimball SR, Jefferson LS. Contribution of insulin to the translational control of protein synthesis in skeletal muscle by leucine. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 282: E1092–E1101, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Babij P, Booth FW. Alpha-actin and cytochrome c mRNAs in atrophied adult rat skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 254: C651–C656, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bar-Shai M, Carmeli E, Reznick AZ. The role of NF-kappaB in protein breakdown in immobilization, aging, and exercise: from basic processes to promotion of health. Ann NY Acad Sci 1057: 431–447, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bentzinger CF, Romanino K, Cloetta D, Lin S, Mascarenhas JB, Oliveri F, Xia J, Casanova E, Costa CF, Brink M, Zorzato F, Hall MN, Ruegg MA. Skeletal muscle-specific ablation of raptor, but not of rictor, causes metabolic changes and results in muscle dystrophy. Cell Metab 8: 411–424, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bodine SC, Latres E, Baumhueter S, Lai VK, Nunez L, Clarke BA, Poueymirou WT, Panaro FJ, Na E, Dharmarajan K, Pan ZQ, Valenzuela DM, DeChiara TM, Stitt TN, Yancopoulos GD, Glass DJ. Identification of ubiquitin ligases required for skeletal muscle atrophy. Science 294: 1704–1708, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Butler DT, Booth FW. Muscle atrophy by limb immobilization is not caused by insulin resistance. Horm Metab Res 16: 172–174, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Childs TE, Spangenburg EE, Vyas DR, Booth FW. Temporal alterations in protein signaling cascades during recovery from muscle atrophy. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 285: C391–C398, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Churchward-Venne TA, Breen L, Phillips SM. Alterations in human muscle protein metabolism with aging: Protein and exercise as countermeasures to offset sarcopenia. BioFactors 40: 199–205, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clavel S, Coldefy AS, Kurkdjian E, Salles J, Margaritis I, Derijard B. Atrophy-related ubiquitin ligases, atrogin-1 and MuRF1 are up-regulated in aged rat Tibialis Anterior muscle. Mech Ageing Dev 127: 794–801, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corradetti MN, Inoki K, Guan KL. The stress-inducted proteins RTP801 and RTP801L are negative regulators of the mammalian target of rapamycin pathway. J Biol Chem 280: 9769–9772, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dardevet D, Sornet C, Bayle G, Prugnaud J, Pouyet C, Grizard J. Postprandial stimulation of muscle protein synthesis in old rats can be restored by a leucine-supplemented meal. J Nutr 132: 95–100, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dickinson JM, Fry CS, Drummond MJ, Gundermann DM, Walker DK, Glynn EL, Timmerman KL, Dhanani S, Volpi E, Rasmussen BB. Mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 activation is required for the stimulation of human skeletal muscle protein synthesis by essential amino acids. J Nutr 141: 856–862, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Drummond MJ, Fujita S, Abe T, Dreyer HC, Volpi E, Rasmussen BB. Human muscle gene expression following resistance exercise and blood flow restriction. Med Sci Sports Exercise 40: 691–698, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Drummond MJ, Miyazaki M, Dreyer HC, Pennings B, Dhanani S, Volpi E, Esser KA, Rasmussen BB. Expression of growth-related genes in young and older human skeletal muscle following an acute stimulation of protein synthesis. J Appl Physiol 106: 1403–1411, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edstrom E, Altun M, Hagglund M, Ulfhake B. Atrogin-1/MAFbx and MuRF1 are downregulated in aging-related loss of skeletal muscle. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 61: 663–674, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ellisen LW. Growth control under stress: mTOR regulation through the REDD1-TSC pathway. Cell Cycle 4: 1500–1502, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ellisen LW, Ramsayer KD, Johannessen CM, Yang A, Beppu H, Minda K, Oliner JD, McKeon F, Haber DA. REDD1, a developmentally regulated transcriptional target of p63 and p53, links p63 to regulation of reactive oxygen species. Mol Cell 10: 995–1005, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glynn EL, Fry CS, Drummond MJ, Timmerman KL, Dhanani S, Volpi E, Rasmussen BB. Excess leucine intake enhances muscle anabolic signaling but not net protein anabolism in young men and women. J Nutr 140: 1970–1976, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gomes MD, Lecker SH, Jagoe RT, Navon A, Goldberg AL. Atrogin-1, a muscle-specific F-box protein highly expressed during muscle atrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 14440–14445, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gordon BS, Kazi AA, Coleman CS, Dennis MD, Chau V, Jefferson LS, Kimball SR. RhoA modulates signaling through the mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) in mammalian cells. Cell Signal 26: 461–467, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gordon BS, Kelleher AR, Kimball SR. Regulation of muscle protein synthesis and the effects of catabolic states. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 45: 2147–2157, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greig CA, Gray C, Rankin D, Young A, Mann V, Noble B, Atherton PJ. Blunting of adaptive responses to resistance exercise training in women over 75y. Exp Gerontol 46: 884–890, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guillet C, Prod'homme M, Balage M, Gachon P, Giraudet C, Morin L, Grizard J, Boirie Y. Impaired anabolic response of muscle protein synthesis is associated with S6K1 dysregulation in elderly humans. FASEB J 18: 1586–1587, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hao Y, Jackson JR, Wang Y, Edens N, Pereira SL, Alway SE. beta-Hydroxy-beta-methylbutyrate reduces myonuclear apoptosis during recovery from hind limb suspension-induced muscle fiber atrophy in aged rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 301: R701–R715, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heinemeier KM, Olesen JL, Haddad F, Schjerling P, Baldwin KM, Kjaer M. Effect of unloading followed by reloading on expression of collagen and related growth factors in rat tendon and muscle. J Appl Physiol 106: 178–186, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hwee DT, Bodine SC. Age-related deficit in load-induced skeletal muscle growth. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 64: 618–628, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iadevaia V, Huo Y, Zhang Z, Foster LJ, Proud CG. Roles of the mammalian target of rapamycin, mTOR, in controlling ribosome biogenesis and protein synthesis. Biochem Soc Trans 40: 168–172, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Katsanos CS, Kobayashi H, Sheffield-Moore M, Aarsland A, Wolfe RR. Aging is associated with diminished accretion of muscle proteins after the ingestion of a small bolus of essential amino acids. Am J Clin Nutr 82: 1065–1073, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Katsanos CS, Kobayashi H, Sheffield-Moore M, Aarsland A, Wolfe RR. A high proportion of leucine is required for optimal stimulation of the rate of muscle protein synthesis by essential amino acids in the elderly. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 291: E381–E387, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kelleher AR, Kimball SR, Dennis MD, Schilder RJ, Jefferson LS. The mTORC1 signaling repressors REDD1/2 are rapidly induced and activation of p70S6K1 by leucine is defective in skeletal muscle of an immobilized rat hindlimb. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 304: E229–E236, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim J, Kundu M, Viollet B, Guan KL. AMPK and mTOR regulate autophagy through direct phosphorylation of Ulk1. Nat Cell Biol 13: 132–141, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lang CH, Pruznak A, Navaratnarajah M, Rankine KA, Deiter G, Magne H, Offord EA, Breuille D. Chronic alpha-hydroxyisocaproic acid treatment improves muscle recovery after immobilization-induced atrophy. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 305: E416–E428, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lang SM, Kazi AA, Hong-Brown L, Lang CH. Delayed Recovery of Skeletal Muscle Mass following Hindlimb Immobilization in mTOR Heterozygous Mice. PLoS One 7: e38910, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin L, Qian Y, Shi X, Chen Y. Induction of a cell stress response gene RTP801 by DNA damaging agent methyl methanesulfonate through CCAAT/enhancer binding protein. Biochemistry 44: 3909–3914, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu JP. Molecular mechanisms of aging and related diseases. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 41: 445–458, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Machida S, Booth FW. Regrowth of skeletal muscle atrophied from inactivity. Med Sci Sports Exerc 36: 52–59, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Magne H, Savary-Auzeloux I, Migne C, Peyron MA, Combaret L, Remond D, Dardevet D. Contrarily to whey and high protein diets, dietary free leucine supplementation cannot reverse the lack of recovery of muscle mass after prolonged immobilization during ageing. J Physiol 590: 2035–2049, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maiese K, Chong ZZ, Shang YC, Wang S. mTOR: on target for novel therapeutic strategies in the nervous system. Trends Mol Med 19: 51–60, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marzetti E, Calvani R, Cesari M, Buford TW, Lorenzi M, Behnke BJ, Leeuwenburgh C. Mitochondrial dysfunction and sarcopenia of aging: from signaling pathways to clinical trials. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 45: 2288–2301, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McGhee NK, Jefferson LS, Kimball SR. Elevated corticosterone associated with food deprivation upregulates expression in rat skeletal muscle of the mTORC1 repressor, REDD1. J Nutr 139: 828–834, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McGlory C, White A, Treins C, Drust B, Close GL, Maclaren DP, Campbell IT, Philp A, Schenk S, Morton JP, Hamilton DL. Application of the [γ-32P]ATP kinase assay to study anabolic signaling in human skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol 116: 504–513, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miyazaki M, Esser KA. REDD2 is enriched in skeletal muscle and inhibits mTOR signaling in response to leucine and stretch. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 296: C583–C592, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morris RT, Spangenburg EE, Booth FW. Responsiveness of cell signaling pathways during the failed 15-day regrowth of aged skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol 96: 398–404, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nair KS. Aging muscle. Am J Clin Nutr 81: 953–963, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.O'Keefe MP, Perez FR, Kinnick TR, Tischler ME, Henriksen EJ. Development of whole-body and skeletal muscle insulin resistance after one day of hindlimb suspension. Metabolism 53: 1215–1222, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rennie MJ. Anabolic resistance: the effects of aging, sexual dimorphism, and immobilization on human muscle protein turnover. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 34: 377–381, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Risson V, Mazelin L, Roceri M, Sanchez H, Moncollin V, Corneloup C, Richard-Bulteau H, Vignaud A, Baas D, Defour A, Freyssenet D, Tanti JF, Le-Marchand-Brustel Y, Ferrier B, Conjard-Duplany A, Romanino K, Bauche S, Hantai D, Mueller M, Kozma SC, Thomas G, Ruegg MA, Ferry A, Pende M, Bigard X, Koulmann N, Schaeffer L, Gangloff YG. Muscle inactivation of mTOR causes metabolic and dystrophin defects leading to severe myopathy. J Cell Biol 187: 859–874, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Siu PM, Alway SE. Aging alters the reduction of pro-apoptotic signaling in response to loading-induced hypertrophy. Exp Gerontol 41: 175–188, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stein TP, Wade CE. Metabolic consequences of muscle disuse atrophy. J Nutr 135: 1824S–1828S, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Strawbridge WJ, Shema SJ, Balfour JL, Higby HR, Kaplan GA. Antecedents of frailty over three decades in an older cohort. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 53: S9–S16, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Suetta C, Frandsen U, Jensen L, Jensen MM, Jespersen JG, Hvid LG, Bayer M, Petersson SJ, Schroder HD, Andersen JL, Heinemeier KM, Aagaard P, Schjerling P, Kjaer M. Aging affects the transcriptional regulation of human skeletal muscle disuse atrophy. PLoS One 7: e51238, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Symons TB, Schutzler SE, Cocke TL, Chinkes DL, Wolfe RR, and Paddon-Jones D. Aging does not impair the anabolic response to a protein-rich meal Am J Clin Nutr 86: 451–456, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Symons TB, Sheffield-Moore M, Wolfe RR, Paddon-Jones D. A moderate serving of high-quality protein maximally stimulates skeletal muscle protein synthesis in young and elderly subjects. J Am Diet Assoc 109: 1582–1586, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Timmerman KL, Lee JL, Fujita S, Dhanani S, Dreyer HC, Fry CS, Drummond MJ, Sheffield-Moore M, Rasmussen BB, Volpi E. Pharmacological vasodilation improves insulin-stimulated muscle protein anabolism but not glucose utilization in older adults. Diabetes 59: 2764–2771, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Whitney ML, Jefferson LS, Kimball SR. ATF4 is necessary and sufficient for ER stress-induced upregulation of REDD1 expression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 379: 451–455, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wilkes EA, Selby AL, Atherton PJ, Patel R, Rankin D, Smith K, Rennie MJ. Blunting of insulin inhibition of proteolysis in legs of older subjects may contribute to age-related sarcopenia. Am J Clin Nutr 90: 1343–1350, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.You JS, Park MN, Song W, Lee YS. Dietary fish oil alleviates soleus atrophy during immobilization in association with Akt signaling to p70s6k and E3 ubiquitin ligases in rats. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 35: 310–318, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]