Abstract

Background

Chronic respiratory conditions are increasingly becoming a cause of health concern with India attributing 11% of its mortality due to non-communicable diseases to chronic respiratory conditions. Chronic bronchitis and asthma take a large toll in terms of morbidity. Lesser number of studies have mentioned their counts of these conditions affecting women in rural area and therefore the present study was conducted with the objectives of determining the prevalence and correlates of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases (COPD) in an area of a primary health centre in rural central India.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted in 24 villages of the study area. Women aged 40 years or more were interviewed using the IUATLD questionnaire. Chronic bronchitis was measured by using the standard criteria for chronic bronchitis, that is, “Presence of cough with expectoration for more than 3 months in a year for the past two or more years”.

Results

Prevalence of chronic bronchitis among women was found to be 2.7%. Factors like older age, presence of a cattle shed within house premises, storage of fertilizers inside house, history of allergy, past history of pulmonary tuberculosis emerged as significant correlates of chronic bronchitis.

Conclusions

The present study provides an insight into the prevalence of chronic bronchitis among rural women exposed to several epidemiological determinants and an opportunity to address the modifiable risk factors.

Keywords: Chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases, Rural, Women, Chronic bronchitis

Introduction

The disease profile of the world is changing at an astonishingly fast rate, especially in low and middle income countries. Non-communicable diseases (NCDs), principally cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, cancers, and chronic respiratory diseases, caused an estimated 35 million deaths in 2005. This figure represents 60% of all deaths globally, with 80% of deaths due to NCDs occurring in low- and middle income countries.1 Of the non-communicable diseases, chronic respiratory diseases afflict hundreds of millions of adults worldwide with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) being one of the most serious and debilitating disease. In the year 2005, when measured in Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs), the burden of chronic respiratory disease was projected to account for nearly 4% of the global burden and nearly 8.3% of the burden of chronic diseases.2 With demographic changes in the developing world and some of the changes in health care system, education, awareness and income, the burden of communicable disease is likely to lessen, however the burden of chronic respiratory diseases including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma and lung cancer are likely to worsen because of increasing tobacco use, environmental hazards and ageing population.3

Rural women in developing countries bear the largest share of this burden resulting from chronic exposure to biomass fuel smoke. Much of the reported prevalence of the respiratory morbidities in our country come from studies conducted in the urban areas although most of the Indian population lives in rural areas. Also, the estimates of respiratory morbidities in females who are exposed to biomass fuels for cooking and second hand tobacco smoke has been less reported and less studied. This study was therefore conducted in the rural settings to study the prevalence and correlates of self-reported chronic bronchitis in women as it is one of the important chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Material and methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted in the area covered by a primary health centre in rural Central India. The primary health centre covered a total of 24 villages and a total population of 35,948. Women residing in the study area, aged 40 years or more, and able to respond to the interview themselves, formed the study population. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee. It was carried out from December 2010 to April 2012.

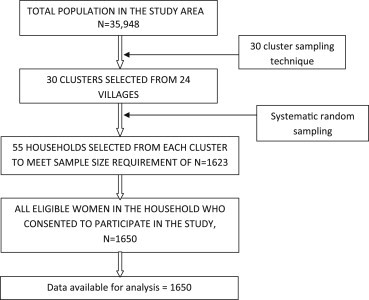

The sample size was calculated by taking into consideration, the prevalence of chronic bronchitis in Indian setting to be 2%, as reported by Chhabra et al, in 2008.4 Considering this as the minimal expected prevalence and an alpha error of 5%; an absolute error of 1% in the estimate of prevalence, a non-response rate of 10% and the design effect of 2.0 (because of multistage sampling) the sample size was estimated to be 1623 (adjusted for population). A 30-cluster sampling method was used to select the study participants. Probability Proportionate to Size (PPS) was used to draw 30 clusters from the 24 villages. A total 55 households were studied in each cluster to meet the sample size requirement of 1623. The households in each cluster were identified by systematic random sampling. All married women of age 40 years and above in the selected family were included in the study and interviewed on obtaining consent (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart explaining selection of study subjects.

On visiting the sampled household, initially a rapport was established and then an informed written consent was taken from the eligible participant, i.e., women of age 40 years and above in the family. Following consent, the participant was interviewed using a pretested questionnaire, the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (IUATLD) bronchial symptoms questionnaire.5–7 The questionnaire used to collect information on respiratory symptoms also had some additional questions in the first part containing questions related to the socio-demographic profile of the individuals and the second part included some questions on presence of some risk factors or correlates of chronic bronchitis. Finally, the last part of the questionnaire (adapted from the IUATLD questionnaire) was used for obtaining information on presence of respiratory symptoms for the diagnosis of chronic bronchitis.

In the present study, chronic bronchitis was measured by using the standard criteria for chronic bronchitis, that is, “presence of cough with expectoration for more than 3 months in a year for the past two or more years”.8

The data was entered and analysed using software SPSS version 12. For studying epidemiological correlates we used odds ratio as a measure of association. 95% confidence interval (95% CI) was also calculated for odds ratio. Chronic bronchitis was taken as dependent variable while age, education, occupation, income, BMI, type of family, type of kitchen, cooking fuel, presence of cattle shed, pets, storage of fertilizers and pesticides in house, tobacco consumption and exposure to second hand tobacco smoke, history of allergy and tuberculosis and frequency of fruits consumption were taken as independent variables. Logistic regression using backward likelihood ratio method was carried out for multivariate analysis to derive the final model for correlates of chronic bronchitis. A p-value <0.05 was taken to be significant.

Results

Most women in this study belonged to age group 40–49 years, while only 10.3% were of age 70 years and above. Of the 1650 women 40.6% were illiterate, 41.8% were educated till 8th standard, while 17.6% were educated till 9th standard or above. Majority of women were labourers (64.4%) and lived in nuclear families (51.6%). The mean annual per capita income in the poorest quintile was 6666.7 (±1636.8), while in the highest (richest) income quintile was INR 29,166.7 (±8916.9). Also, 28.5% had a BMI less than normal (<18.5), while 24.1% were either overweight or obese.

Of the 1650 women, 20.5% lived in kuchha houses, 43.1% lived in semi-pucca houses and 36.4% lived in pucca houses. 92.3% of the present study population had an indoor type of kitchen (with 82.6% having separate kitchen inside house and 9.7% not having a separate kitchen inside house) while only 7.7% had an outdoor type of kitchen. With regards to use of cooking fuel, 25.1% reported using LPG for cooking, 0.7% using kerosene oil and 74.2% of using wood as their cooking fuel. Also, majority of the study subjects were exposed to cooking for 26–50 years (57.8%) although all women were not cooking regularly currently. In the present study, 15.7% of women reported consumption of smokeless forms of tobacco and 9.3% reported exposure to second hand tobacco smoke. Of the 1650 women, 22.1% reported having cattle shed in house premises, 15.6% had pets in their homes, 3.8% stored fertilizers and 3.3% stored pesticides in their homes. Also, in the present study, 6.9% of the study subjects reported to have history of allergy, 4% reported a positive family history of allergy and 6.5% reported a positive family history of asthma. 1% of the studied women also had suffered from pulmonary tuberculosis in the past (Table 1).

Table 1.

Risk factors for chronic bronchitis on bivariate analysis.

| Correlates | Examined (%) (N = 1650) | Chronic bronchitis |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | ||

| Ageb | |||

| 40–49 | 727 (44.1) | 1.00 | |

| 50–59 | 339 (20.5) | 0.85 | 0.23–2.68 |

| 60–69 | 414 (25.1) | 2.32 | 1.01–5.52 |

| 70 and above | 170 (10.3) | 8.46 | 3.84–19.43 |

| Educationb | |||

| Illiterate | 670 (40.6) | 7.00 | 1.95–43.71 |

| 1st to 8th standard | 689 (41.8) | 2.56 | 0.64–16.95 |

| 9th standard and above | 291 (17.6) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Occupation | |||

| Housework | 530 (32.1) | 3.29 | 0.61–69.26 |

| Labourer | 1062 (64.4) | 0.82 | 0.14–17.65 |

| Service/Business | 58 (3.5) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Type of family | |||

| Joint | 799 (48.4) | 1.00 | – |

| Nuclear | 851 (51.6) | 1.34 | 0.73–2.46 |

| Income quintilea | |||

| 1st (poorest) | 6666.7 ± 1636.8 | 1.44 | 0.60–3.57 |

| 2nd | 10000.0 ± 741.5 | 1.25 | 0.52–3.08 |

| 3rd | 13333.3 ± 1127.2 | 0.39 | 0.10–1.25 |

| 4th | 18333.3 ± 1734.4 | 0.65 | 0.21–1.87 |

| 5th (richest) | 29166.7 ± 8916.9 | 1.00 | – |

| Type of house | |||

| Kuchha | 339 (20.5) | 1.58 | 0.75–3.27 |

| Semi-pucca | 600 (36.4) | 0.97 | 0.47–2.01 |

| Pucca | 711 (43.1) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Type of kitchen | |||

| Indoor | 1523 (92.3) | 3.75 | 0.72–77.14 |

| Outdoor | 127 (7.7) | 1.00 | – |

| Cooking fuel used | |||

| LPG | 414 (25.1) | 1.00 | – |

| Kerosene oil | 11 (0.7) | 5.03 | 0.21–36.2 |

| Wood | 1225 (74.2) | 1.53 | 0.73–3.56 |

| Exposure to cookingb | |||

| ≤25 years | 500 (30.3) | 1.00 | – |

| 26–50 years | 954 (57.8) | 1.43 | 0.61–3.68 |

| >50 years | 196 (11.9) | 7.53 | 3.18–19.54 |

| Cattle shedb | |||

| Present | 365 (22.1) | 2.66 | 1.43–4.84 |

| Absent | 1285 (77.9) | 1.00 | – |

| Pets | |||

| Present | 257 (15.6) | 1.36 | 0.61–2.80 |

| Absent | 1393 (84.4) | 1.00 | – |

| Storage of fertilizersb | |||

| Yes | 62 (3.8) | 3.39 | 1.14–8.44 |

| No | 1588 (96.2) | 1.00 | – |

| Storage of pesticides | |||

| Yes | 55 (3.3) | 2.13 | 0.51–6.42 |

| No | 1595 (96.7) | 1.00 | – |

| BMIb | |||

| <18.5 | 471 (28.5) | 2.23 | 1.15–4.39 |

| 18.5–22.99 | 781 (47.3) | 1.00 | – |

| ≥23 | 398 (24.1) | 0.98 | 0.39–2.29 |

| Tobacco consumption (smokeless)b | |||

| Present | 259 (15.7) | 5.02 | 2.72–9.2 |

| Absent | 1391 (84.3) | 1.00 | – |

| Second hand tobacco smoke exposure | |||

| Present | 154 (9.3) | 2.16 | 0.92–4.58 |

| Absent | 1496 (90.7) | 1.00 | – |

| History of allergyb | |||

| Present | 114 (6.9) | 3.05 | 1.30–6.52 |

| Absent | 1536 (93.1) | 1.00 | – |

| Past history of tuberculosisb | |||

| Present | 17 (1.0) | 11.89 | 3.22–36.67 |

| Absent | 1633 (99.0) | 1.00 | – |

| Fruit consumption practices | |||

| Never or occasionally | 1377 (83.5) | 1.29 | 0.57–3.40 |

| At least 1–2 times/week | 273 (16.5) | 1.00 | – |

Note:

Annual per capita income (mean ± SD).

p < 0.05 (using chi-square test).

In the present study, the prevalence of chronic bronchitis was found to be 2.7%. In bivariate analysis of the determinants of chronic bronchitis, higher age, lower education, exposure to cooking for more than 50 years, presence of a cattle shed within house premises, storage of fertilizers inside house, a lower than normal BMI, consumption of smokeless tobacco, history of allergy, a positive family history of asthma and a positive past history of pulmonary tuberculosis emerged as significant risk factors for chronic bronchitis (Table 1). However, all of these did not contribute to the final model derived by logistic regression and significant correlates of chronic bronchitis derived in the final model by logistic regression were: higher age [OR = 5.97; 95% CI: 2.46–14.57]; presence of a cattle shed in house premises [OR = 2.30; 95% CI:1.19–4.46]; storage of fertilizers inside house [OR = 2.93; 95% CI: 1.00–8.60]; smokeless tobacco use [OR = 2.49; 95% CI:1.25–4.99]; history of allergy [OR = 3.50; 95% CI:1.47–8.33]; past history of tuberculosis [OR = 9.08; 95% CI:2.47–34.03] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Correlates of chronic bronchitis on multiple logistic regression.

| Correlates | Chronic bronchitis |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Age (70 years and above) | 5.97 | 2.46–14.57 | <0.001 |

| Cattle shed in house premises | 2.30 | 1.19–4.46 | 0.013 |

| Indoor storage of fertilizers | 2.93 | 1.00–8.60 | 0.049 |

| Smokeless tobacco consumption | 2.49 | 1.25–4.99 | 0.010 |

| History of allergy | 3.50 | 1.47–8.33 | 0.005 |

| Past history of pulmonary tuberculosis | 9.08 | 2.47–34.03 | 0.001 |

Discussion

Less number of studies have been reported, citing the magnitude of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in our country, especially in rural areas, even when national mortality figures for the same has been reported to be 11%.9 The overall prevalence of chronic bronchitis or COPD reported by various studies ranged from 2.7% to 4.15%, which was comparable to the present study.10–12 However, Brashier et al reported the prevalence of chronic bronchitis to be 16% in females above the age of 40 years in their study in the slums of Pune city.13 This highlights that the health conditions in urban slums are worse than that in rural areas.

Older age was an important correlate of chronic bronchitis in the present study and similar finding has been reported from a study in non-smoking rural women in southern India and from another multi-centric study.10,11 With advancing age, the lung function declines and superimposed cumulative years of exposure to environmental and other risk factors may be the possible reason for the increase in morbidity in the higher age groups.

The odds of having chronic bronchitis was higher in those with a cattle-shed adjacent to house compared to those who did not have an adjacent cattle shed. Cattle-shed is a source of animal borne allergens, which possibly is a reason for the higher association in subjects of chronic bronchitis and so in the present study. Brashier et al have reported a similar finding from an urban slum based study around Pune. The American Thoracic Society has reported in their publication, exposure to fertilizers as respiratory health hazard.14 In the present study, significantly higher odds of having chronic bronchitis was found in women who stored fertilizers in their house. Although association of chronic bronchitis with fertilizers has not been reported in similar setting, long-term exposure to cholinesterase-inhibiting agricultural pesticides currently in use in India has been associated with a reduction in lung function, COPD and a rise in respiratory symptoms by Chakraborty et al.15 This finding in the present study, thus consolidates the above cited evidence in literature.

Consumption of smokeless tobacco emerged as a significant correlate of chronic bronchitis. Though most studies have not reported a similar association, a higher odds of mortality due to COPD in those who consumed smokeless tobacco has been reported from a cohort study.16 Tobacco consumption is significantly higher in poor and less educated in India, however, in the present study an independent association of smokeless tobacco consumption with chronic bronchitis was found even after adjusting for these confounders. History of allergy or atopy was another important correlate of chronic bronchitis. Allergy or atopy has been strongly associated with asthma and there is evidence to asthma being an important risk factor for development of COPD. Although history of allergy as an independent risk factor for COPD has not been reported by any of the studies in similar settings, the risk has been documented in literature.17 Airflow obstruction varies in patients of COPD with co-existing tuberculosis from 28% to 68% and the present study also finds significant association of past history of pulmonary tuberculosis with COPD.17

Although India has devised a national programme for prevention and control of cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and stroke (NPCDCS); for blindness; mental disorders and deafness to address the challenge of major non-communicable diseases, none have been devised for chronic respiratory conditions like chronic bronchitis and asthma. Considering the high prevalence of risk factors and considerably high mortality due to COPD (11%),9 a national programme is urgently needed. However, the Indian government has been instrumental in introducing legislation which may limit the potential risk factors for COPD, which includes the passing of the national anti - tobacco legislation in 2008, banning smoking in public places throughout the country which may therefore have a positive impact in reducing the conditions associated with these factors. The present study reveals that some modifiable correlates are amenable to behaviour change in the rural population like tobacco consumption, proper storage of fertilizers and construction of cattle shed in appropriate distance from the living place. Health promotion and prevention programmes should therefore focus on these risk factors which are primarily modifiable through behaviour change interventions. Looking into the future, one cannot ignore the changing demographics of the world population and the reality is that chronic respiratory diseases like COPD remain important diseases globally. Our greater understanding of the disease pathogenesis, prognosis and treatment should result in better outcomes for many of our patients. Cautious prevention strategies should reduce the burden of the disease on the nation and globally.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . WHO; Geneva: 2008. 2008–2013 Action Plan for the Global Strategy for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bousquet J., Khalteav N. WHO; Geneva: 2007. Global Surveillance, Prevention and Control of Chronic Respiratory Diseases. A Comprehensive Approach. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization . WHO; Geneva: 2002. WHO Strategy for Prevention and Control of Chronic Respiratory Diseases; pp. 7–8. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chhabra P., Sharma G., Kannan A.T. Prevalence of respiratory disease and associated factors in an urban area of Delhi. Indian J Community Med. 2008;33:229–232. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.43227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burney P.G., Laitinen L.A., Perdrizet S. Validity and repeatability of the IUATLD (1984) Bronchial Symptoms Questionnaire: an international comparison. Eur Respir J. 1989;2:940–945. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ravault C., Kauffmann F. Validity of the IUATLD (1986) questionnaire in the EGEA study. International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. Epidemiological study on the Genetics and Environment of Asthma, bronchial hyperresponsiveness and atopy. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2001;5:191–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leon Fabregas M., de Diego Damia A., Perpina Tordera M. Usefulness of the IUATLD respiratory symptoms questionnaire for the differential diagnosis of bronchial asthma and chronic bronchitis. Arch Bronconeumol. 2000;36(8):441–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bousquet J., Khaltaev N., editors. Global Surveillance, Prevention and Control of Chronic Respiratory Diseases – A Comprehensive Approach. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization, Regional Office for South East Asia . WHO Regional Office for SEAR; New Delhi, India: 2011. Non-communicable Diseases in the South-East Asia Region. 2011 Situation and Response. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jindal S.K., Aggarwal A.N., Chaudhry K. A multicentric study on epidemiology of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and its relationship with tobacco smoking and environmental tobacco smoke exposure. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2006;48:23–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson P., Balakrishnan K., Ramaswamy P. Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in rural women of Tamilnadu: implications for refining disease burden assessments attributable to household biomass combustion. Glob Health Action. 2011;4:7226. doi: 10.3402/gha.v4i0.7226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Behera D., Jindal S.K. Respiratory symptoms in Indian women using domestic cooking fuels. Chest. 1991;100:385–388. doi: 10.1378/chest.100.2.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brashier B., Londhe J., Madas S., Vincent V., Salvi S. Prevalence of self-reported respiratory symptoms, asthma and chronic bronchitis in slum area of a rapidly developing Indian city. Open J Respir Dis. 2012;2(3):73–81. http://www.scirp.org/journal/PaperInformation.aspx?paperID=21607 [Online] [cited 2012 August 10] Available from: URL: [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Thoracic Society Respiratory health hazards in agriculture. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158:S1–S76. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.supplement_1.rccm1585s1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chakraborty S., Mukherjee S., Roychoudhury S., Siddique S., Lahiri T., Ray M.R. Chronic exposures to cholinesterase-inhibiting pesticides adversely affect respiratory health of agricultural workers in India. J Occup Health. 2009;51(6):488–497. doi: 10.1539/joh.l9070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gupta P.C., Pednekar M.S., Parkin D.M., Sankaranarayanan R. Tobacco associated mortality in Mumbai (Bombay) India. Results of the Bombay cohort study. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34:1395–1402. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salvi S.S., Barnes P.J. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in non-smokers. Lancet. 2009;374:733–743. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61303-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]