Abstract

Background

Vancomycin Resistant Enterococci (VRE) are a major cause of nosocomial infections. There are various phenotypic and genotypic methods of detection of glycopeptide resistance in enterococci. This study utilizes multiplex PCR for reliable detection of various glycopeptides resistance genes in VRE.

Method

This study was conducted to detect and to assess the prevalence of vancomycin resistance among enterococci isolates. From October 2011 to June 2013, a total of 96 non-repetitive isolates of enterococci from various clinical samples were analyzed. VRE were identified by Kirby Bauer disc diffusion method with Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines. Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of all isolates for vancomycin and teicoplanin was determined by E-test. Multiplex PCR was carried out for all enterococci isolates using six sets of primers.

Results

Out of 96 isolates, 14 (14.6%) were found to be resistant to vancomycin by vancomycin E-test method (MIC ≥32 μg/ml). Out of these 14 isolates, 13 were also resistant to teicoplanin (MIC ≥16 μg/ml). VanA gene was detected in all the 14 isolates by Multiplex PCR. One of the PCR amplicons was sent for sequencing and the sequence received was submitted in the GenBank (GenBank accession no. KF181100).

Conclusion

Prevalence of VRE in this study was 14.6%. Multiplex PCR is a robust, sensitive and specific technique, which can be used for rapid detection of various glycopeptide resistance genes. Rapid identification of patients infected or colonized with VRE is essential for implementation of appropriate control measures to prevent their spread.

Keywords: Vancomycin resistant enterococci, Minimum inhibitory concentration, Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Multiplex PCR, GenBank

Introduction

Enterococci have evolved over the past century from being an intestinal commensal organism of little clinical significance to becoming one of the most common nosocomial pathogens associated with significant morbidity and mortality.1, 2 Enterococci are important because of their role as the leading cause of nosocomial infections which have a significant role in dissemination and persistence of drug resistance genes.3

Vancomycin is a member of a class of antibiotics referred to as glycopeptides therefore vancomycin resistant enterococci (VRE) can also be referred to as Glycopeptide resistant enterococci (GRE). Six types of glycopeptides resistance have been described in enterococci that can be distinguished on the basis of the sequence of the structural gene for the resistance ligase (vanA, vanB, vanC, vanD, vanE, vanG).4

VanA type resistance is characterized by high-level resistance to vancomycin and teicoplanin, whereas VanB type strains are resistant to variable levels of vancomycin, but susceptible to teicoplanin.5VanD type strains are resistant to moderate level of vancomycin and low level of teicoplanin.6 There are three VanC genes namely Van C1, Van C2 and Van C3. These genes are specific to the motile VRE species Enterococcus gallinarum, Enterococcus casseliflavus and Enterococcus flavescens respectively.7 The Van C2 and Van C3 genotypes are closely related and are usually referred to as Van C2/C3. The VanE resistant phenotype is an inducible type of resistance to low levels of vancomycin that exhibit full susceptibility to teicoplanin.

Resistance to glycopeptides is disseminating rapidly and has spread to methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus.8 Rapid identification of VRE colonized patient is thus essential for detection of such clinical isolates to prevent the spread of VRE.

The aim of the study was to identify enterococci at species level by phenotypic methods and detect vancomycin resistance genes (van alphabet) by multiplex PCR.

Materials and methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted from October 2011 to June 2013. A total of 96 non-repetitive clinical isolates of enterococci were identified from various clinical samples. Detailed history of the patients was recorded which included age, sex, location, diagnosis, duration of hospitalization and exposure to antibiotics.

Identification of enterococci: The isolates were identified at the species level with the help of conventional phenotypic methods which included Gram's stain, colony morphology, catalase test, bile esculin test, growth in 6.5% NaCl, mannitol fermentation, arginine dihydrolase test, motility test, arabinose fermentation, lactose fermentation and sucrose fermentation.

Antibiotic susceptibility testing: Antibiotic susceptibility testing was carried out using Vancomycin disc (30 μg, HiMedia) and the results were interpreted according to CLSI guidelines. Zone size <14 mm was considered resistant and zone size >17 mm considered sensitive.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) determination: Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of vancomycin and teicoplanin for all 96 isolates was determined by E-test (bioMerieux) and the results were interpreted according to CLSI guidelines. MIC ≥32 μg/ml for vancomycin and teicoplanin was considered resistant.

Multiplex PCR

DNA extraction: DNA extraction was done from all isolates of enterococci using the QIAamp DNA mini kits from QIAGEN, Germany. Manufacturer's instructions were followed for extracting DNA from the fresh cultures.

Primers: Primers were procured from Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT), Inc. and are shown in Table 1.4

Table 1.

Primers used in the multiplex PCR.

| Primera | Sequence (5′ → 3′) | Gene | Positionb | Size of PCR product |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| vanA(+) vanA(−) |

GGGAAAACGACAATTGC GTACAATGCGGCCGTTA |

van A | 176–192 907–891 |

732 |

| vanB(+) vanB(−) |

ACGGAATGGGAAGCCGA TGCACCCGATTTCGTTC |

van B | 169–185 815–799 |

647 |

| vanC(+) vanC(−) |

ATGGATTGGTAYTKGTATc TAGCGGGAGTGMCYMGTAAc |

van C1/2 | 133–150/142–159 947–929/968–950 |

815/827 |

| vanD(+) vanD(−) |

TGTGGGATGCGATATTCAA TGCAGCCAAGTATCCGGTAA |

van D | 357–375 856–837 |

500 |

| vanE(+) vanE(−) |

TGTGGGATCGGAGCTGCAG ATAGTTTAGCTGGTAAC |

van E | 364–382 793–777 |

430 |

| vanG(+) vanG(−) |

CGGCATCCGCTGTTTTTGA GAACGATAGACCAATGCCTT |

van G | 68–86 1008–989 |

941 |

+, Sense primer; −, antisense primer.

Nucleotide numbering begins at the initiation codon of the gene.

K = G or T; M = A or C; Y C or T.

PCR reaction mixtures: PCR reaction mixtures were prepared under laminar flow under strict precautions to prevent cross contamination. For a single sample reaction of 50 μl volume, various reagents were used as mentioned in Table 2.

Table 2.

Various reagents used in PCR reaction mixture.

| Reagent | Volume (μl) | Final concentration |

|---|---|---|

| Autoclaved Distilled water | 19.35 | – |

| PCR buffer (10×) with MgCl2 (15 mM) | 5 | 1×, 1.5 mM |

| dNTP (10 mM) | 0.25 | 50 μM |

| Primer vanA (forward) | 1.25 | 0.5 μM |

| Primer vanA (reverse) | 1.25 | 0.5 μM |

| Primer vanB (forward) | 1.25 | 0.5 μM |

| Primer vanB (reverse) | 1.25 | 0.5 μM |

| Primer vanC (forward) | 1.25 | 0.5 μM |

| Primer vanC (reverse) | 1.25 | 0.5 μM |

| Primer vanD (forward) | 1.25 | 0.5 μM |

| Primer vanD (reverse) | 1.25 | 0.5 μM |

| Primer vanE (forward) | 1.25 | 0.5 μM |

| Primer vanE (reverse) | 1.25 | 0.5 μM |

| Primer vanG (forward) | 1.25 | 0.5 μM |

| Primer vanG (reverse) | 1.25 | 0.5 μM |

| Taq DNA Polymerase (250U/μl) | 0.4 | 2U/μl |

| DNA Template | 10 | – |

| Total | 50 | – |

Amplification was carried out with the following thermal cycling profile: initial denaturation for 3 min at 94 °C, 35 cycles of amplification consisting of 1 min at 94 °C, 1 min at 45 °C, and 1 min at 72 °C, with 7 min at 72 °C for the final extension.

Gel electrophoresis: DNA fragments were analyzed by electrophoresis in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA on a 1% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide.

Sequencing: One of the PCR amplicons was sent for sequencing and was submitted in GenBank (Accession number – KF181100).

Results

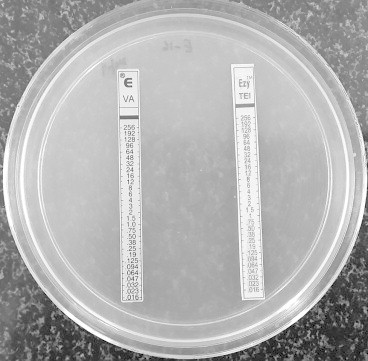

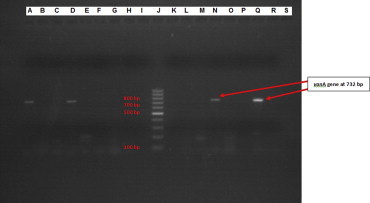

Out of 96 isolates of enterococci, 70 (∼73%) were Enterococcus faecalis and 26 (∼27%) were Enterococcus faecium. A total of 14 isolates were found to be vancomycin resistant by Kirby–Bauer disc diffusion method and E-test. 13 isolates showed high level resistance to both vancomycin and teicoplanin (MIC > 256 μg/ml) by E-test (Fig. 1). One isolate showed high level resistance to vancomycin (MIC > 256 μg/ml) only and susceptibility to teicoplanin (MIC 2 μg/ml). 11 out of 26 isolates (42.3%) of E. faecium and 3 out of 70 (4.3%) isolates of E. faecalis were found to be resistant to vancomycin. All the 96 isolates were subjected to Multiplex PCR using 6 sets of primers as already described. VanA gene (bp size 732) was found to be present in 14 isolates (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

E-test showing MIC of vancomycin and teicoplanin against vancomycin-resistant strain of Enterococcus faecium (MIC >256 μg/ml).

Fig. 2.

Analysis of PCR product by gel electrophoresis showing band at 732 base pair denoting vanA gene. A – positive control of vanA gene, band at 732 bp (E. faecium ATCC 51559) B – negative control D, N, Q – clinical isolates showing band at 732 bp denoting vanA gene J – 100 bp molecular marker.

One of the PCR products isolated from urine sample from a patient of ICU (Medical) suffering from Chronic lymphoid leukemia was sent for sequencing. The sequence obtained was submitted is the GenBank, Bethesda, Maryland, USA, and the accession number provided was KF181100.

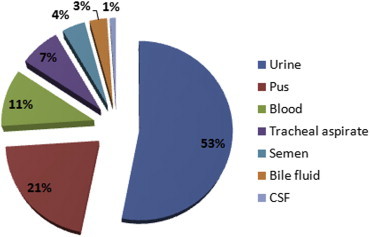

The most common clinical sample from which enterococci were isolated was urine. The distribution of various clinical samples is given in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Distribution of enterococcal isolates from various clinical samples.

The average duration of hospitalization of all the patients was 9.04 days whereas that of patients with VRE and non-VRE was 13.42 days and 7.3 days respectively.

Out of 96 isolates, 26 were from ICU, 40 from various wards and 30 were from OPD. Ten isolates from ICU (38.5%) and 04 isolates from various wards (10%) were found to be VRE, whereas no VRE was detected from OPD patients.

A total of 24 patients were suffering from one or the other malignancy and were on immunosuppressive drugs or were neutropenic, 16 had surgical site infection (SSI) and 10 had CKD. Ten isolates from patients with malignancy (41.7%), 2 isolates from patients with CKD (20%) and 1 isolate from patients with SSI (6.25%) were vancomycin resistant.

Discussion

Enterococci colonize the bowels of more than 90% of healthy humans. E. faecalis accounts for more than 80% of the enterococcal isolates in clinical samples, but in recent years E. faecium has become more common, probably because of its greater antibiotic resistance particularly to vancomycin.9, 10, 11 For the last two decades, enterococci have been the 3rd most common cause of hospital-acquired infections (HAI) after E. coli and S. aureus and ahead of Pseudomonas aeruginosa.12, 13 The most common nosocomial infection caused by enterococci are urinary tract infections (associated with instrumentation and antimicrobial administration) followed by intra-abdominal and pelvic infections. They also cause surgical site infections, bacteremia, endocarditis, neonatal sepsis and rarely meningitis.9, 14

In this study of 96 enterococcal isolates, the prevalence of vancomycin resistance enterococci was found to be 14.6%, which is very high. In the study of 291 enterococcal isolates by Deshpande et al, the prevalence of vancomycin resistance was found to be 19.6%.15 All the other studies from India have reported a prevalence of less than 10%. The high prevalence of vancomycin resistance among enterococci in the present study might be because of the increased vancomycin selection pressure, as this being a tertiary care centre, most of the patients are referred and have already been exposed to various antibiotics including vancomycin and cephalosporins. The vancomycin resistance was more prevalent in E. faecium (42.3%) than in E. faecalis (4.3%). Overall the vancomycin MIC levels of the 14 VRE isolates were very high (>256 μg/ml) indicating high-level resistance. The MIC of teicoplanin of 13 isolates was >256 μg/ml indicating high-level resistance to teicoplanin. As only 13 isolates showed high level resistance to both vancomycin and teicoplanin, it seemed that vanA gene was present in these 13 isolates. However, the results of multiplex PCR were only slightly different as vanA gene was detected in all the 14 isolates. Thus multiplex PCR is a better, sensitive and specific technique for detection of glycopeptide resistance genes.

The patients from whom vancomycin resistant enterococci were isolated had increased duration of hospitalization (average duration 13.4 ± 2.3 days) as compared to patients from whom vancomycin sensitive enterococci were isolated (average duration 7.3 ± 4.83 days). Moreover all the patients from whom VRE was isolated had recent exposure to antibiotics during their hospitalization suggesting that prolonged hospitalization and prior exposure to antibiotics increases the risk of VRE.

Vancomycin resistant isolates were most commonly isolated from ICU (38.5%) followed by various wards (10%). All isolates of enterococci isolated from OPD were vancomycin sensitive. This suggests that the risk of VRE increases with the severity of the disease condition.

Most of the patients from whom VRE was isolated were suffering from malignancy and were on immunosuppressives or were severely neutropenic. This indicates that the risk of VRE increases with the degree of immunosuppression.

Conclusion

The prevalence of vancomycin resistance among enterococci isolates in this study is 14.6%, which is quite high. The resistance was found to be more common in E. faecium than in E. faecalis. Multiplex PCR can detect glycopeptide resistance genes with high sensitivity and specificity with a short turnaround time. The study shows that vanA gene is prevalent in this part of the country. This study also brings out the fact that the risk factors for vancomycin resistant enterococci were prolonged hospitalization, prior exposure to antibiotics, severity of disease condition and degree of immunosuppression.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Giridhara Upadhayay P.M., Ravikumar K.L., Umapathy B.L. Review of virulence factor of Enterococcus: an emerging nosocomial pathogen. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2009;27:301–305. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.55437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schouten M.A., Hoogkamp-Korstanje J.A., Meis J.F., Voss A. Prevalence of vancomycin resistant enterococci in Europe. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2000;19:816–822. doi: 10.1007/s100960000390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rahimi F., Talebi M., Saife M., Pourshaffie M.R. Distribution of enterococcal species and detection of vancomycin resistance genes by Multiplex PCR in Tehran sewage. Iran Biomed J. 2007;11:161–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Depardieu F., Perichon B., Courvalin P. Detection of the van alphabet and identification of enterococci and staphylococci at the species level by multiplex PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;42:5857–5860. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.12.5857-5860.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arthur M., Reynolds P., Courvalin P. Glycopeptide resistance in Enterococci. Trends Microbiol. 1996;4:401–407. doi: 10.1016/0966-842X(96)10063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Depardieu F., Kolbert M., Pruul H., Bell J., Courvalin P. Van D type vancomycin resistant Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus faecalis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:3892–3904. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.10.3892-3904.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hernandez X.P., Alvarez S.M., Martin F.C. A PCR assay for rapid detection of vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Diagnostic Microbiol Infect Disease. 2002;42:273–277. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(01)00360-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang S., Dawn M., Sievert M.S. Infection with vancomycin resistant Staphylococcus aureus containing the van-A resistance gene. N Engl J Med. 2003;384:1342–1347. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa025025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koneman E.W., Allen S.D., Janda W.M., Schrekenberger P.C., Winn W.C., editors. Color Atlas and Textbook of Diagnostic Microbiology. 5th ed. JB Lippincott; New York: 1997. The gram positive cocci Part II: Streptococci, Enterococci and the “Streptococcus-like” Bacteria; pp. 577–649. [Chapter 12] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murray B.E. The life and times of the Enterococcus. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1990;3:46–65. doi: 10.1128/cmr.3.1.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moellering R.C., Jr. Emergence of enterococcus as a significant pathogen. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;14:1173–1178. doi: 10.1093/clinids/14.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control Nosocomial infection surveillance 1984. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1986;35(SS 1):17SS–29SS. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schaberg D.R., Culver D.H., Gaynes R.P. Major trends in the microbial etiology of nosocomial infections. Am J Med. 1991;91:72S–75S. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(91)90346-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Forbes B.A., Sahm D.F., Weissfield A.S., editors. Bailey and Scott's Diagnostic Microbiology. 10th ed. Mosby; London: 1998. Laboratory methods for detection of antibacterial resistance; pp. 250–272. [Chapter 18] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deshpande V.R., Karmarkar M.G., Mehta P.R. Prevalence of multidrug resistant enterococci in a tertiary care hospital in Mumbai, India. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2013;7(2):155–158. doi: 10.3855/jidc.3018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]