Abstract

Machado–Joseph disease (MJD) has been described in Africans, but no cases have been reported from Nigeria. Current MJD global distribution results from both the ancestral populations-of-origin and the founder effects of mutations, some as a consequence of the Portuguese sea travels in the 15th to 16th century. Two main ancestral haplotypes have been identified: the Machado lineage, which is more recent, predominant in families of Portuguese extraction, and the Joseph lineage, which is much older and worldwide spread, postulated to have an Asian origin. We report a Nigerian family with MJD from Calabar, once settled by Portuguese slave traders, and assessed its mutational origin. The proband was a 33-year-old man with progressive unsteady gait, weakness of all limbs, dysphagia, dysarthria, urinary frequency and diaphoresis. He had end-of-gaze nystagmus, spastic quadriparesis and atrophic small muscles of the hand. He showed fibrillation potentials on EMG, and nerve conduction studies suggested a central axonopathy without demyelination. This family bears the Joseph haplotype, which has a founder effect in the island of Flores, in the Azores (and their descendants in North-America), but is also the most common in non-Portuguese populations worldwide, with an estimated mutation age of around 7000 years.

INTRODUCTION

Machado–Joseph disease (MJD/SCA3) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder, with diverse clinical manifestations, including ataxia, progressive external opthalmoplegia, pyramidal signs, basal ganglia symptoms, dystonia and distal amyotrophies.1, 2 MJD is the most common of the ∼30 recognized, dominantly inherited forms of ataxia. Its highest frequency is described in Brazil, Portugal and China.3 The Portuguese sea travels of the late 15th and 16th centuries have been suggested as possible explanation for the presence of MJD in countries like India, China, Japan, Yemen and parts of Africa, all in the Portuguese slave trade routes.4 MJD has been found in a few African families, including those from Morocco, Algeria, Ghana, Ivory Coast, Mali, Somalia and families of African descent in the USA.5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 Whether independent mutational origin(s) underlie all these families remains unclear as haplotype studies are scarce. The presence of MJD worldwide is mainly explained by two ancestral lineages: the first seems to have occurred about 7000 years ago, in Asia (TTACAC, or the Joseph lineage, seen in the vast majority of non-Portuguese families, in the five continents), and another, more recent, which occurred less than 2000 years ago, responsible for MJD in some regions of Portugal (as the island of São Miguel, in the Azores and the Tagus valley) and in a few other families of proven or suspected Portuguese ancestry (GTGGCA, or the Machado lineage).5, 7, 8 Calabar, capital city of the Cross River state in southeastern Nigeria, was a major slave trading port from the late 17th to the 19th century.11 MJD has not been reported in Nigeria to the best of our knowledge. We report a family with MJD in Nigeria, originating from Calabar, a region with ancestral connection to Portuguese explorers and slave traders, and assess its mutational origin.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

The proband and four other individuals from a Nigerian family have been genotyped in this study after obtaining their consent. We performed the identification of MJD lineages7, 12 and genotyping of allelic variants along a 4 kb region flanking the MJD expansion8 as previously described.

RESULTS

The proband was a 33-year-old man with a strong family history of a neurological disorder diagnosed as MJD. He was apparently well until the age of 30, when he developed an unsteady gait, associated with progressive non-painful weakness of all limbs (worsened by cold), and difficulty in lifting heavy objects. There was blurring of vision, speech difficulty, dysphagia without odynophagia and occasional nasal food regurgitation, but no emotional liability or cognitive decline. He had no difficulty getting up from a stooping position or from a low seat or when combing his hair. He had no history of accompanying numbness, paresthesiae or altered temperature sensations, but had diaphoresis, urinary frequency and weight loss. He had no history of preceding or associated febrile illness, headache, vomiting, seizures or behavioral abnormality. His physical examination revealed a tall (height 1.85 m), slim, young adult, with long arm span (1.86 m), but no high arched palate or other Marfanoid features. There was no cognitive impairment. He had oscillatory end-of-gaze nystagmus, with 9th/10th cranial nerve palsy, dysphonia with nasal quality to the voice and scanning dysarthria. Motor system revealed a broad based and stiff gait, atrophic intrinsic muscles of the hand, thenar and hypothenar eminences and a prominent anatomic snuff box. He also had prominent medial malleoli and interdigital spaces on the dorsum of the deformed feet. There were no fasciculations. He had spastic quadriparesis (grade 4+/5− on the MRC scale), with global deep tendon hyperreflexia, brisk jaw jerk and extensor plantar response on the right, but flexor on the left. Abdominal reflex was absent in all quadrants. He had dysmetria with past and pre-pointing, as well as dysdiadochokinesis. There was no objective sensory loss. His electromyography and nerve conduction studies revealed abnormal amplitude M wave and fibrillation potentials, with positive sharp and polyphasic waves, suggesting an axonopathy. The normal conduction velocity, latencies and absence of temporal dispersion suggested that there was no accompanying myelinopathy. Diagnosis of MJD was confirmed by DNA analysis. His current medication consists of antiplatelet drugs, because of the relative immobility, as well as neurovitamins, in addition to physiotherapy.

We assessed the haplotype background of expanded alleles from this family as previously described.7, 8 The entire region of 4 kb encompassing the expansion includes 16 SNPs: all alleles on the MJD haplotype were shared by this family and the previously defined Joseph lineage (Table 1). To gain insight into the possible source of introduction of the mutation in the Nigerian population, we also genotyped four flanking fast-evolving markers (STRs). Although we could not assess, by segregation, the allelic phase of the most distant STR downstream, the extended haplotype 13-22-(CAG)Exp-14-16/18 has not been observed in Portuguese or any other genotyped MJD families.

Table 1. SNP-based haplotypes of the Nigerian family with MJD compared with the Joseph (Flores) and Machado (São Miguel) lineages.

| dbSNP ID | refSNP (HGVS)a | Distance from the (CAG)n (bp)b | Machado lineage | Joseph lineage | Nigerian family |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs12590497 | chr14:g.92549632C>A | 12 352 | G | T | G/T |

| rs16999141 | chr14: g.92549586G>A | 12 306 | T | T | T |

| rs10146519 | chr14: g.92548896A>C | 11 616 | T | G | T/G |

| rs1048755 | chr14:g.92548785C>T | 11 505 | G | A | G/A |

| rs12586535 | chr14: g.92538529G>A | 1249 | C | T | T |

| rs12586471 | chr14: g.92538405A>G | 1125 | T | C | C |

| rs56268847 | chr14: g.92538168T>C | 888 | A | A | A |

| rs10467858 | chr14: g.92537785C>T | 505 | G | A | A |

| rs10467857 | chr14: g.92537743G>C | 463 | G | G | G |

| rs10467856 | chr14: g.92537732A>G | 452 | T | C | C |

| (CTG)exp g.92537355_92537357(87) | |||||

| rs12895357 | chr14:g.92537354C>G | 1 | G | C | C |

| rs7158733 | chr14:g.92537223G>T | 132 | C | A | A |

| rs3092822 | chr14: g.92537163T>G | 192 | A | C | C |

| rs77086230 | chr14: g.92536013G>A | 1 342 | C | C | C |

| rs79316375 | chr14: g.92535391G>A | 1964 | C | C | C |

| rs8004149 | chr14: g.92534915C>T | 2440 | G | A | A |

| rs111735934 | chr14: g.92534883C>T | 2472 | A | G | G |

| rs181752420 | chr14: g.92534779G>A | 2576 | C | C | C |

| rs7142326 | chr14: g.92534741T>C | 2614 | G | G | G |

| rs74071847 | chr14: g.92534673G>A | 2742 | C | C | C |

Genome Reference Consortium GRCh37.p10 (hg19 database).

The four most distant SNPs are outside the 4 kb sequenced region.

Discussion

In several African-American MJD families, including the first one in which MJD was suspected,9 patients presented prominent Parkinsonian features (MJD subtype 4). This clinical presentation, although common among patients of African extraction, is rare in families of European extraction.10 The hypothesis of cis effects responsible for this variation has, however, been weakened by the absence of a haplotype shared by all families with type 4 MJD; instead, trans-acting genetic factors could explain this rare presentation in a restricted ethnic background.10 The proband from a Nigerian family had, however, type 2 MJD with no Parkinsonian features. In general, heterogeneity of neurologic findings in MJD seems to be partly explained by duration of the disease, clinical type and CAG repeat length. Previously, nystagmus, eyelid retraction, rigidity, bradykinesia and optic atrophy were hardly attributable to any factor, speculating that they could be independent neurological markers.13 Diaphoresis and urinary frequency suggested the involvement of the autonomic system. Clinical analysis and neuropathological reports in the literature indicate that autonomic nervous system involvement is common and might be important, although often overlooked.4, 13 The most frequent manifestation is urinary disturbance. Sequeiros and Coutinho4 reported difficulty in sphincter control in 5.8% of 143 Portuguese patients. The nationwide epidemiological survey in Japan14 revealed voiding dysfunction in 31.3% of 66 patients, whereas Yeh et al15 in Taiwan reported that 53% of their patients had urinary disturbance (nocturia and/or incontinence) and more than half of the patients had abnormal sudomotor function.

There are, as yet, no approved therapies for MJD, but symptomatic management should be pursued. Amantadine and buspirone have been tried to improve coordination and balance, with uncertain impact. Neuroprotective or neurorestorative therapies and neuro-rehabilitation remain the mainstay of treatment. This includes physical, occupational, speech and swallowing therapy, adaptive equipment, nutritional counseling, home health assistance, genetic and psychosocial counseling and support groups with special assistance and support for the caregiver.

The ancestral origin of the MJD mutation and the presence of founder effects that would account for the worldwide distribution of the disease have been the source of much speculation over the years.4, 5, 7 Previous haplotype studies have shown different genetic backgrounds associated with expanded alleles in patients of African origin: AGA, ACA and GCC (rs1048755–rs12895357–rs7158733).5, 7, 10 These suggested that (1) the disease heterogeneity (namely, type 4 MJD) cannot be explained exclusively by the haplotype background and (2) more than one mutational origin has been introduced in Africa. These studies included the genotyping of a few SNPs that, when analyzed together with other markers, proved to be very informative for clarifying the mutational origin in populations with a large number of families. Nevertheless, while studying a single family (mainly when haplotype data from related populations are not available), a more refined analysis is needed. We followed, thus, a different approach by sequencing a 4 kb region encompassing the (CAG)n in the proband and his relatives (Figure 1). This region, which includes 16 SNPs, can be compared with both the Joseph and Machado lineages (TTACAC and GTGGCA, respectively), as the full region has been previously assessed in many families from these lineages.8 This family from Nigeria shared all 16 SNPs with the Joseph ancestral haplotype (Table 1). Taking into account that this mutation is spread worldwide, we also assessed flanking STR-based haplotypes, to compare them with those from different populations and gain insight into the migration route responsible for the presence of MJD in Nigeria. Although the MJD haplotype in this Nigerian family has not been found in any other population, it is phylogenetically closer to MJD haplotypes genotyped in European populations, than in Asia. Further larger genetic studies in the Nigerian population are needed for probable cases of MJD, as well as a larger study of African affected families.

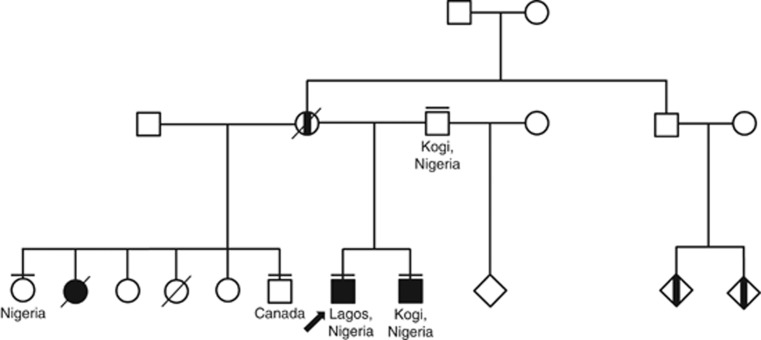

Figure 1.

Pedigree structure of the Nigerian family affected with Machado–Joseph disease. Filled symbols designate patients with MJD, and those half-filled represent patients not observed (affected by history only). Arrow indicates proband; a short line above the symbol indicates relatives sampled and genotyped for analysis of the expanded CAG repeat on the ATXN3 gene, and used for the haplotype study.

Acknowledgments

SM is the recipient of a scholarship (SFRH/BPD/77969/2011) from the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT); IPATIMUP is partially supported by FCT. This work was co-financed by the European Social Fund (Human Potential Thematic Operational Programme).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Coutinho P, Andrade C. Autosomal dominant system degeneration in Portuguese families of the Azores Islands. A new genetic disorder involving cerebellar, pyramidal, extrapyramidal and spinal cord motor functions. Neurology. 1978;28:703–709. doi: 10.1212/wnl.28.7.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima L, Coutinho P. Clinical criteria for diagnosis of Machado–Joseph disease: report of a non-Azorean Portuguese family. Neurology. 1980;30:319–322. doi: 10.1212/wnl.30.3.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sequeiros J, Martins S, Silveira I. Epidemiology and population genetics of degenerative ataxias. Handb Clin Neurol. 2012;103:227–251. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-51892-7.00014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sequeiros J, Coutinho P. Epidemiology and clinical aspects of Machado–Joseph disease. Adv Neurol. 1993;61:139–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaspar C, Lopes-Cendes I, Hayes S, et al. Ancestral origins of the Machado–Joseph disease mutation: a worldwide haplotype study. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:523–528. doi: 10.1086/318184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhmann C, Bussopulos A, Oechsner M. Dopaminergic response in Parkinsonian phenotype of Machado–Joseph disease. Mov Disord. 2003;18:219–221. doi: 10.1002/mds.10322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins S, Calafell F, Gaspar C, et al. Asian origin for the worldwide-spread mutational event in Machado–Joseph disease. Arch Neurol. 2007;64:1502–1508. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.10.1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins S, Soong BW, Wong VC, et al. Mutational origin of Machado–Joseph disease in the Australian Aboriginal communities of Groote Eylandt and Yirrkala. Arch Neurol. 2012;69:746–751. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.2504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healton EB, Brust JC, Kerr DL, Resor S, Penn A. Presumably Azorean disease in a presumably non-Portuguese family. Neurology. 1980;30:1084–1089. doi: 10.1212/wnl.30.10.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramony SH, Hernandez D, Adam A, et al. Ethnic differences in the expression of neurodegenerative disease: Machado–Joseph disease in Africans and Caucasians. Mov Disord. 2002;17:1068–1071. doi: 10.1002/mds.10241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovejoy PE.Historical settingin Metz HC (ed): Nigeria: A Country Study Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress; 19911–83. [Google Scholar]

- Martins S, Coutinho P, Silveira I, et al. Cis-acting factors promoting the CAG intergenerational instability in Machado–Joseph disease. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2008;147B:439–446. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jardim LB, Pereira ML, Silveira I, Ferro A, Sequeiros J, Giugliani R. Neurologic findings in Machado–Joseph disease: relation with disease duration, subtypes, and (CAG)n. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:899–904. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.6.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirayama K, Takayanagi T, Nakamura R, et al. Spinocerebellar degenerations in Japan: a nationwide epidemiological and clinical study. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl. 1994;153:1–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1994.tb05401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh TH, Lu CS, Chou YH, et al. Autonomic dysfunction in Machado–Joseph disease. Arch Neurol. 2005;62:630–636. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.4.630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]