Abstract

The combination of family-based linkage analysis with high-throughput sequencing is a powerful approach to identifying rare genetic variants that contribute to genetically heterogeneous syndromes. Using parametric multipoint linkage analysis and whole exome sequencing, we have identified a gene responsible for microcephaly (MCP), severe visual impairment, intellectual disability, and short stature through the mapping of a homozygous nonsense alteration in a multiply-affected consanguineous family. This gene, DIAPH1, encodes the mammalian Diaphanous-related formin (mDia1), a member of the diaphanous-related formin family of Rho effector proteins. Upon the activation of GTP-bound Rho, mDia1 generates linear actin filaments in the maintenance of polarity during adhesion, migration, and division in immune cells and neuroepithelial cells, and in driving tangential migration of cortical interneurons in the rodent. Here, we show that patients with a homozygous nonsense DIAPH1 alteration (p.Gln778*) have MCP as well as reduced height and weight. diap1 (mDia1 knockout (KO))-deficient mice have grossly normal body and brain size. However, our histological analysis of diap1 KO mouse coronal brain sections at early and postnatal stages shows unilateral ventricular enlargement, indicating that this mutant mouse shows both important similarities as well as differences with human pathology. We also found that mDia1 protein is expressed in human neuronal precursor cells during mitotic cell division and has a major impact in the regulation of spindle formation and cell division.

Introduction

Microcephaly (MCP) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by a small cranium with a significantly reduced occipito-frontal head circumference. The reduced brain volume is particularly evident within the cerebral cortex and is often associated with some degree of intellectual disability (ID). MCP is categorized as either primary (MCP vera) or syndromic, indicating the presence of other physical or neurological deficits or gross structural brain abnormalities. Mendelian forms of MCP have been identified, representing both dominant and recessive forms of inheritance.1, 2, 3 In the present study, we report a consanguineous Saudi Arabian pedigree with a novel syndromic form of MCP, involving small head size, ID, seizures, short stature, and blindness. Genome-wide linkage analysis identified a maximum LOD score of 3.7 under a recessive model of inheritance mapping to chromosome 5q31.3. Whole-exome sequencing (WES) and targeted sequencing analyses identified a rare, nonsense, homozygous sequence variant c.2332C>T (p.Gln778*, RefSeq NM_005219.4) in the gene DIAPH1 (mouse symbol is Diap1) (MIM 602121) encoding the mammalian diaphanous-related formin, mDia1. The encoded protein has previously been implicated in neuronal migration of cortical interneurons,4 autosomal hearing loss,5 and myelodysplasia.6 Depending upon the cell type and position in the cell cycle, mDia1 has been shown to localize to the cell cortex, trafficking endosomes, cleavage furrow, mid-bodies, and centrosomes, the cytoplasmic microtubule-organizing center crucial for cell division.7 These properties are shared with several other primary microcephaly genes, including WDR62 (Homo sapiens WD repeat domain 62),2, 8, 9 CENPJ (centromere protein J),10 CEP152 (centrosomal protein 152 kDa),11 ASPM (abnormal spindle-like MCP-associated (Drosophila)),12 and CEP135 (centrosomal protein 135 kDa).13 Interestingly, analysis of Diap1-deficient mice revealed cerebral ventricular enlargement but not the reduction in brain volume and blindness observed in the human phenotype. Thus, DIAPH1 has a crucial role in brain development and exhibits species differences in its function.

Materials and methods

The study protocol was approved by the Yale Human Investigation Committee (HIC). Approval from the institutional review board for genetic studies and informed written consent from the family were obtained by the referring physician in the Alhada Military Hospital, Taif, Saudi Arabia. Nucleotide numbers are in reference to cDNA (NM_005219.4 where A of the ATG translational start site is designated as +1) and amino acid number is in reference to protein (O60610) coordinates.

Neuroimaging

Magnetic resonance images (MRIs) containing axial, sagittal, and coronal TI- and T2-weighted images were obtained from patient IV:7 in this pedigree. The corpus callosum, posterior fossa structures (the cerebellum, midbrain, pons, and medulla), deep gray matter, degree of myelination, and presence of any associated malformations were assessed on each MRI.

Genotyping, targeted sequencing, and WES

Genomic DNA derived from whole blood was genotyped using the 1Mv1 Duo Bead array chips (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. SNPs showing Mendelian inconsistency in transmission were removed14 and data were pruned to 42 703 SNPs that are in minimal linkage equilibrium with each other using linkage disequilibrium (LD)-based SNP pruning with the following criteria: pairwise correlation coefficient r2<0.23 within a 50-SNP window; proportion of missing genotypes <5%, relative minor allele frequency >5%, and Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium 0.0001 among the controls and cases. Family relatedness was ascertained through estimation of identity by descent. The LOD score was calculated with pruned SNPs using Allegro 1.2 (DeCode genetics Inc., Reykjavik, Iceland).

DNA from both patient IV:4 and the unaffected father were sequenced using a custom-designed NimbleGen Sequence Capture 385K array (>60 bp probes to sequence the target linkage region; Roche Nimblegen, Inc., Madison, WI, USA) and later data from patient IV:4 using WES according to the manufacturer's protocol. WES was conducted as previously described.2 The sequence reads were mapped to the human genome (NCBI/hg19). Variants were confirmed by Sanger sequencing. DIAPH1 sequence alteration and other variations (Supplementary Tables 4 and 6) found in patient IV:4 were submitted to the LOVD public database (http://databases.lovd.nl/shared/individuals/00004216).

DIAPH1 screening in independent cases and control groups

All 28 exons comprising DIAPH1 were evaluated in the following individuals: (1) 62 Turkish and Middle Eastern subjects found to have regions of homozygosity corresponding to chromosome 5q31, presenting one or more of the following conditions: MCP, lissencephaly, polymicrogyria, cerebellar hypoplasia, schizencephaly, corpus callosum hypogenesis, demyelination, psychosomatic motor delay, ID, epilepsy, and autism; (2) 136 Turkish probands, including 120 from consanguineous and 16 from non-consanguineous families presenting with MCP; and (3) 100 neurologically normal control individuals from Saudi Arabia. PCR primer sequences and conditions are available upon request.

Quantitative PCR and western blot analysis

DIAPH1 mRNA expression in Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-transformed lymphoblastoid cells (LCLs) available from four affected individuals and both parents was assessed by real-time-PCR (RT-PCR) using DIAPH1 and the reference gene TBP (TATA box-binding protein) primers with the PCR efficiency of >90% (slope=−3.2 and −3.6) and R2 99%. Relative changes in gene expression were analyzed with the ΔCT method.15 Cell lysates from LCLs of four affected individuals, parents, and an independent control were used for western blot analysis. We used primary rabbit anti-DIAPH1 antibodies from N-terminus (1:10 000, Abcam-ab11172, Cambridge, MA, USA) and C-terminus (1:5000, Bethyl Labs-A300–078, Montgomery, TX, USA). Anti-GAPDH (1:200) was used as the loading control.

Cellular localization of mDia1

ReNcell CX cells from the immortalized fetal human cortical neural progenitor cell line (Millipore-SCC007, Billerica, MA, USA) were fixed in 4% PFA and blocked by blocking solution (5% normal donkey serum, 1% BSA, 0.1% glycine, 0.1% lysine, and 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS). Fixed cells were incubated with mouse anti-mDia1 (1:50, Santa Cruz-sc-373807, Dallas, TX, USA) and rabbit anti-pericentrin (1:500, Covance-PRB-432C, Princeton, NJ, USA). Alexa Fluor 488 Donkey Anti-Mouse IgG and Alexa Fluor 594 Donkey Anti-Rabbit IgG were used as secondary antibodies (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA). DNA was visualized with DAPI. Cells were imaged with an Aperio microscope (Aperio Technologies, Vista, CA, USA).

Human and mouse brain specimens

The study protocol was approved by the HIC. All human tissues were collected under guidelines approved by the Yale HIC and were part of the tissue collection at the Department of Neurobiology. For each tissue donation, appropriate written, informed consent and approval were obtained. All experiments with mice were carried out in accordance with protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Yale University, School of Medicine. diap1-knockout mice are a gift from A S Alberts (Van Andel Institute, MI, USA). The genotype of the diap1-deficient allele was analyzed by PCR using the following primers: Wt F-5′-TAGATAGGGATAAAGTTGGTGGGCTGTG-3′, Wt R-5′-GAGATGTCCTGCAATGACTGAGCAGTGG-3′, and Mut R-5′-GCATCACCTTCACCCTCTCCACTGACAG-3'. The morning of a detectable vaginal plug and the first neonatal day were considered to be embryonic day 0.5 (E0.5) and postnatal day 0 (P0), respectively.

In situ hybridization

For embryonic stages, pregnant females were anesthetized, and pups at E12.5, E14.5, and E17.5 stages were extracted from the uterus. Embryonic brains were dissected and fixed by immersion in 4% PFA. At all postnatal stages (P3, P7, P14), mice were anesthetized with injectable anesthetics and intracardially perfused with 4% PFA. Brains were postfixed overnight in 30% sucrose/4% PFA, and sectioned in the coronal plane on a Leica sledge cryomicrotome at 36 μm. Sections were processed for nonradioactive in situ hybridization. The RNA probes complementary to mouse diap1 (bases 3062–3861 of the mouse diap1 cDNA, NM_007858.2) and human DIAPH1 (bases 2241–3960 of the human DIAPH1 cDNA, NM_005219.4) were labeled with digoxigenin-11-UTP. Sections were analyzed with a Zeiss Stemi dissecting microscope or a Zeiss AxioImager with an AxioCam MRc5 digital camera (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

Immunostaining

For immunostaining, fixed E14.5 and P0 brain tissues were embedded in 4% agarose and sectioned at 50 μm with a Vibratome VT1000S (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). Tissue sections were incubated in primary antibodies (Supplementary Table 5) and with appropriate donkey Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:1000, Invitrogen). Nissl staining was performed using the standard method.

Gene co-expression network

To identify any possible correlation of the DIAPH1 gene with MCP genes (MCPH1 (MIM 607117), WDR62 (MIM 613583), CDK5RAP2 (MIM 608201), ASPM (MIM 605481), CENPJ (MIM 609279), STIL (MIM 181590), and CEP135 (MIM 611423)), we performed co-expression analyses using the previously generated human brain transcriptome data set.16 For each MCP gene, we used Pearson's correlation analysis with other genes, and then chose its top 100 highly correlated genes. Cytoscape software17 was used to visualize the co-expression network, in which genes are shown by circles and the correlated genes are connected by lines. The ‘un-weighted force-directed layout' parameter was used to optimize the network visualization. The human brain data set is generated by exon arrays and is available from the Human Brain Transcriptome database and the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE25219. It covers 16 brain regions over 15 periods, ranging in stage from embryonic development to late adulthood.16 To test the significance of overlapping eight genes between DIAPH1 and CDK5RAP2, permutation analysis was performed. Briefly, we randomly picked two groups with 100 genes in the whole human gene list. We set up the threshold that the number of genes shared by these two groups should be larger than eight. We repeated this operation 10 000 000 times and counted the number of operations that passed the preset threshold. The P value was estimated by the ratio of successful operations.

Results

A new MCP syndrome with temporal pole atrophy, callossal hypotrophy, seizure, and blindness

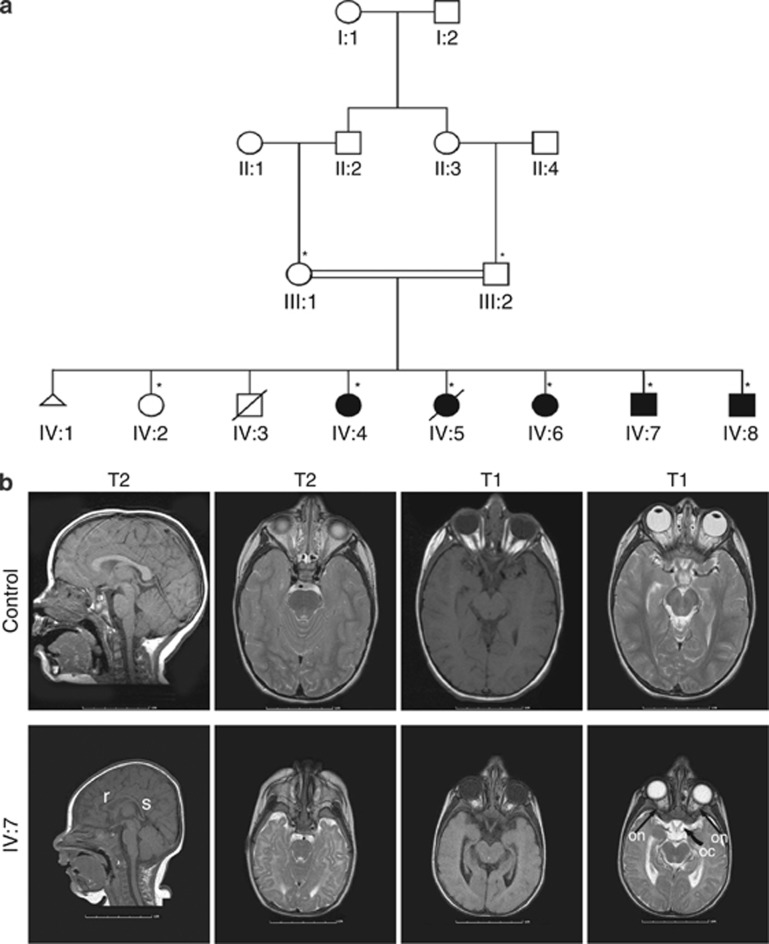

We ascertained a consanguineous family from Saudi Arabia (Pedigree SAR1008) including five (three female and two male) children that came to clinical attention initially at ∼3 months of age because of seizures and were found to have severe MCP (head circumferences more than 3 SD below the mean for age) (Figure 1a and Supplementary Data).

Figure 1.

The pedigree structure and radiographic features of the SAR1008 family. (a) The patients described in this study are numbered. Parents are first cousins and have three affected female (IV:4, IV:5, IV:6), two affected male (IV:7, IV:8) and one unaffected female (IV:2) children. Squares and circles indicate males and females, respectively. Affected individuals are shown as filled symbols. One pregnancy that resulted in miscarriage is shown as a triangle. A diagonal line through a symbol denotes that the individual is deceased. The individuals from whom DNAs were obtained are indicated by *. (b) Representative MRIs of individual IV:7 at 4 months of age and control subject at 3 years of age. Axial T2 and T1 at the level of the temporal lobe, T2 and T1 at the level of the chiasm, and T1 sagittal images are shown (left to right). The MRI reveals temporal pole atrophy with normal cortical thickness. The optic nerves (on) and chiasm (oc) appear normal in size (indicated by arrows). Midline sagittal T1 shows hypoplasia of the rostrum (r) and splenium (s) of the corpus callosum. The scale bars are in cm.

The mother had a history of a single second-trimester miscarriage (IV:1) prior to delivering her first-born child (IV:2). It is not known whether the fetus had MCP. The second offspring (IV:3) was full term, but died at 3 months of age, despite hospitalization in a NICU, because of congenital heart disease. In addition, patient IV:5 recently died at the age of 18 as a result of chest infection.

Clinical examinations of the four oldest affected individuals showed moderate to severe ID, delays in both motor and language development, and severe bilateral visual impairment. Their hearing was grossly normal bilaterally, as was audiological examination. The youngest affected individual, patient IV:8, was assessed at 3 months and 3 weeks of age. He was found to be microcephalic (head circumference less than 3rd percentile); his weight was 5 kg (3rd percentile), and he suffered from seizures and bilateral visual impairment. Additional details of the medical history are presented in the Supplementary data.

T1- and T2 weighted, non-contrast, 1.5T MR imaging revealed that the brain of affected individual IV-7 exhibited a substantial reduction in the size of the cerebral cortex without obvious evidence of abnormal neuronal migration or grossly abnormal architecture (MCP vera). He also had volume loss of the anterior end of the temporal lobe (the temporal pole) with normal cortical thickness suggesting atrophy rather than hypoplasia. There was also loss of volume of the rostrum and splenium of the corpus callosum on midline sagittal T1-weighted images. The optic nerves and chiasm, cerebral aqueduct, and fourth ventricle were normal on midline sagittal T1 (Figure 1b). The subject's small weight and height indicated that body size was also affected.

A homozygous nonsense sequence variant in DAPH1 causes MCP

We performed whole-genome genotyping of all members of the pedigree SAR1008 and confirmed the reported parental relationship of first cousin (found pi-hat=0.15, consistent with a first-cousin union) (Supplementary Table 1). We then performed parametric linkage analysis using both affected and unaffected individuals and specifying a recessive mode of inheritance, penetrance of 99%, a phenocopy rate of 0.01, and a disease allele frequency of 0.0001 using a pruned set of 42 703 SNPs selected on the basis of LD information derived from the Saudi Arabian and Middle Eastern populations.14 We identified a single linkage peak on chromosome 5q31.3 reaching the maximal theoretical LOD score of 3.7 under the specified parameters. This locus is flanked by SNPs rs2907308 and rs164078 and constitutes an approximately 724 kb region containing 38 annotated genes (Figure 2a and Supplementary Table 2). No other region of the genome was found to reach genome-wide significance (Supplementary Figure 1).

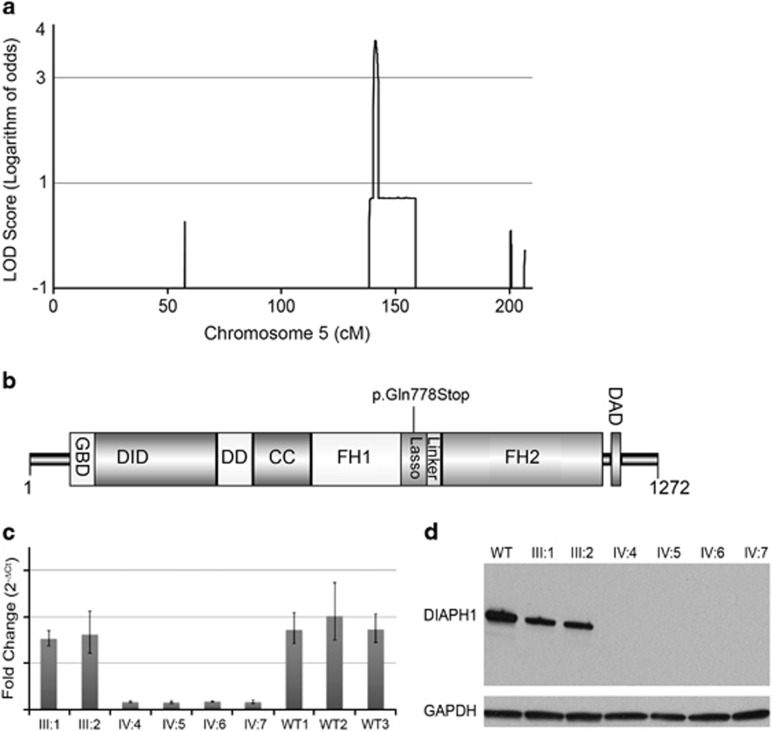

Figure 2.

Identification of a nonsense homozygous sequence variant in the DIAPH1 gene in a family with MCP. (a) Panel shows the results of the parametric linkage analysis for chromosome 5q, expressed as LOD scores. The maximum theoretical LOD score for this family is 3.7 using the genotyping data from IMv1 Duo Bead array chips. The analysis is modeled under the recessive mode of inheritance, penetrance of 99%, a phenocopy rate of 0.01, and a disease allele frequency of 0.0001. (b) Domain organization of mDia1. Abbreviations: GBD, GTPase binding region; DID, diaphanous inhibitory domain; DD, dimerization domain; CC, coiled coil; FH1, formin homology 1 domain; FH2, formin homology 2 domain; DAD, diaphanous autoinhibitory domain. Nonsense sequence variant p.Gln778* results in a 86.2 kDa truncated protein. (c) mRNA levels of DIAPH1 gene in EBV transformed LCLs from homozygous patients (IV:4, IV:5, IV:6, IV:7), and heterozygous parents (III:1 and III:2) were analyzed using RT-PCR. Three individuals of the same ethnicity and without a sequence variant are used as control (WT). (d) Protein blot for mDia1. Lane 1 represents the control subject, lanes 2 and 3 represent the unaffected parents who carry the heterozygous p.Gln778* alteration (III:1 and III:2). Lanes 4, 5, 6, and 7 represent affected individuals with homozygous p.Gln778* alteration (IV:4, IV:5, IV:6, IV:7). The band indicates a molecular weight of ∼140 kDa. GAPDH is used as control (lower band).

Next, in order to identify the disease-causing sequence variant, using the gDNA from proband IV:4, we performed WES as well as targeted sequencing of the LOD-2 confidence interval (138.8–160 cM), achieving a very high level of coverage (Supplementary Table 3). For targeted sequencing, we also used the gDNA from the father, focusing on the LOD-2 confidence interval (138.8–160 cM), using a custom-designed NimbleGen Sequence Capture 385K array based on the Illumina Genome Analyzer IIx platform.

Within the targeted linkage interval, we identified only a single homozygous, nonsense sequence variant affecting the DIAPH1 gene. No other novel homozygous coding insertion or deletion sequence variants were observed within this interval. We identified a total of 15 homozygous missense variants that were reported previously at dbSNP with their minor allele frequencies between 0.086 and 47.2% (Supplementary Table 4). The nonsense sequence variant in DIAPH1, c.2332C>T (r.2473c>u), was predicted to terminate translation at amino acid 778 of 1272 (p.Gln778*, Q778*), leading to a truncated 86 kDa protein lacking the carboxyl-terminus bearing the highly conserved formin homology (FH2) domain that is responsible for mDia1's ability to generate linear actin filaments and affect microtubule dynamics (Figure 2b and Supplementary Figure 2A and B). The presence of the heterozygous sequence variant in both parents was confirmed via Sanger sequencing. Further analysis of WES data did not identify any other rare, segregating LoF (loss-of-function) homozygous sequence variants (Supplementary Table 6) either within or outside the linkage interval.

We anticipated that the mutant allele would lead to nonsense-mediated decay and evaluated the expression via qRT-PCR in the index family. We found a four-fold decrease in DIAPH1 expression in probands relative to their parental controls (Figure 2c). Subsequent western blot analysis showed that all affected subjects lacked the predicted 140 kDa mDia1 protein. The heterozygous parents showed protein expression levels approximately one-half of that observed in an unrelated control (Figure 2d).

Further Sanger sequencing of the complete coding and UTR regions of the DIAPH1 gene in 200 control chromosomes from neurologically normal individuals from Saudi Arabia, a cohort of 136 MCP cases, and 62 consanguineous cases that have homozygosity for the interval surrounding DIAPH1 and at least one of the following phenotypes, ID, seizure, MCP, lissencephaly, polymicrogyria, cerebellar hypoplasia, and/or autism, failed to identify any additional rare, homozygous LoF alterations. These findings strongly suggest that the homozygous loss-of-function sequence variant identified in DIAPH1 and the accompanying absence of protein expression is the underlying genetic cause of the disorder in the index family.

mDia1 is localized pericentrosomally in mitotic neural progenitors

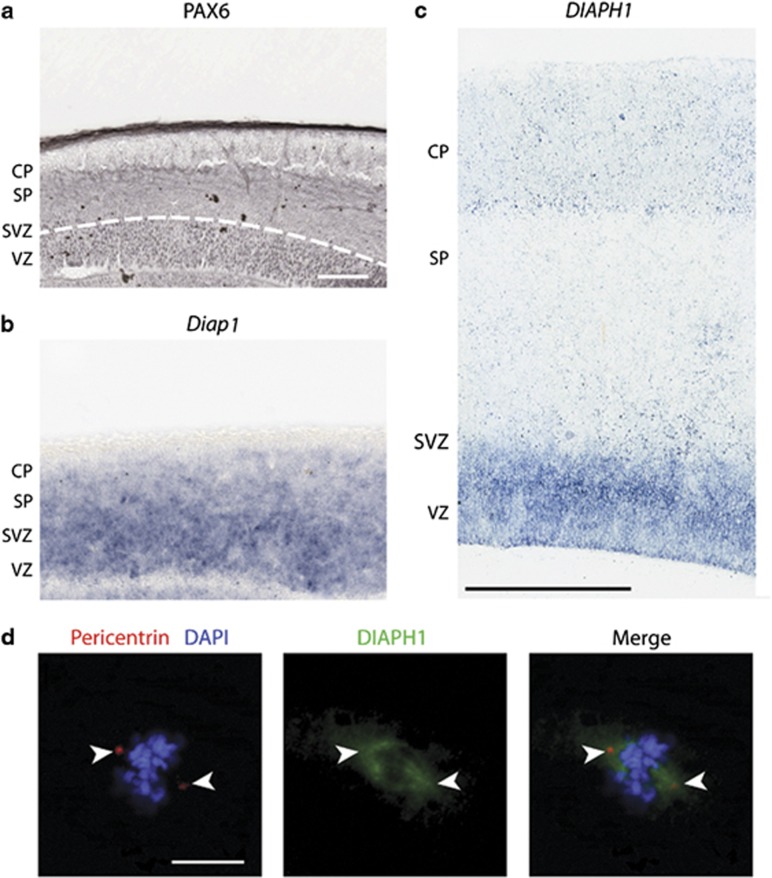

To gain insight into the potential functions of mDia1 in brain development, we analyzed Diap1 mRNA expression in the developing mouse and human forebrain and in hNPCs. In situ hybridization of mouse brain at embryonic days (E) 12.5, 14.5, and 17.5 revealed that Diap1 mRNA was expressed in the ventricular and subventricular zone (VZ and SVZ, respectively) progenitor cells of the dorsal and ventral forebrain and the brainstem (Figures 3a and b). Diap1 was also observed in neurons of the cortex and hippocampus of later embryonic age (Supplementary Figure 3A). During postnatal development, Diap1 expression was detected in the cerebral cortex, basal ganglia, hippocampus, thalamus, and external granular layer of the cerebellum (Supplementary Figure 3B). Similar to mouse Diap1 expression, the human homolog was strongly expressed by VZ and SVZ progenitor cells of the human neocortical wall at 12 weeks post conception (PCW) (Figure 3c).

Figure 3.

Expression pattern and subcellular localization of DIAPH1 in E14.5-day-old mouse brain (this period of development is equivalent to human brain 12 PCW), fetal human brain, and mitotic human cortical neural progenitor cells. A set of two panels from a developing mouse brain (E14.5) indicates (a) PAX6 (under the white line) at VZ, and (b) in situ hybridization shows Diap1 expression at VZ and SVZ. (c) In situ hybridization of early fetal human brain (12 PCW) shows DIAPH1 expression in the VZ and SVZ. The scale bar indicates 100 μm and 600 μm, respectively. See Supplementary Figure 3 for individual panels. (d) Confocal microscopy analysis of fixed human cerebral cortical neural progenitor cells in mitosis (M phase). Cells were co-stained with anti-mDia1 (green), pericentrin (red), and DAPI for DNA (blue). The scale bar indicates 10 μM.

Given that the majority of MCP genes encode proteins that localize to the centrosome or mitotic spindle, we hypothesized that mDia1 would show similar subcellular localization and tested this in hNPCs using immunofluorescence. Double immunofluorescence staining for mDia1 and pericentrin (PCNT), a centrosomal protein, revealed co-localization with centrosomes and mitotic spindles in mitosis (M phase) (Figure 3d).

To gain insight into function we conducted mRNA co-expression analyses to identify genes with similar spatial and temporal expression pattern to DIAPH1 and other previously identified MCP genes in the developing human brain. We used exon-array data derived from human brain covering 16 brain regions over 15 periods, ranging from embryonic development to late adulthood.16 The top 100 most-correlated transcripts of the seed genes, including the seven previously identified MCP genes and DIAPH1, were chosen using Pearson's correlation analysis and visualized with Cytoscape. Using this approach among the other MCP genes, we found that DIAPH1 and CDK5RAP2 are correlated with each other by sharing eight overlapping genes. To test the significance of this overlapping, we performed a permutation test that showed that the overlapping between DIAPH1 and CDK5RAP2 is significant with P-value < 1e−7, suggesting spatio-temporal expression and potential functional overlap between the two genes in particular (Supplementary Figure 4). Together, these findings indicate that, similar to previously identified MCPH genes, mDia1 is localized pericentrosomally in mitotic neural progenitors and shares a number of functionally related co-expressed genes during human brain development.

Mice lacking mDia1 have enlarged lateral ventricles but not MCP

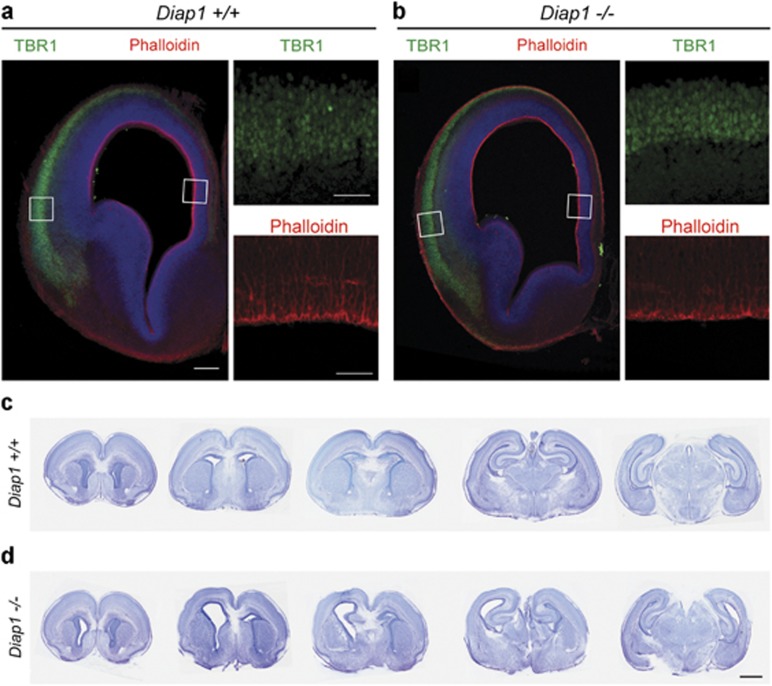

In order to further evaluate the role of mDia1 in embryonic brain development, we examined Diap1-targeted mice (Diap1−/−) lacking mDia1 protein.18 We confirmed the absence of mDia1 protein in the developing forebrain using western blot (Supplementary Figure 5). Consistent with the previous study,19 we found that Diap1−/− mice show normal organization of the cerebral cortex using layer-specific markers, CUX1, BCL11B (also known as CTIP2), and FOXP2 at P0 (Figures 4a and b and Supplementary Figure 6). However, our analysis of tissue sections of Diap1−/− mice with Nissl staining revealed unilateral dilatation of the ventricles in 60% of mutant mice (9 out of 15) with no blockage of the cerebral aqueduct (Figures 4c and d, Supplementary Figures 7). Previous analyses of mice lacking both DIAP1 and DIAP2 (mDia-DKO) had also various degrees of the dilation of the lateral and the third ventricle in all adult mDia-DKO mice and this was due to periventricular dysplasia in the third ventricle resulting in obstruction of CSF circulation.19

Figure 4.

Cortical organization is preserved in the Diap1−/− mouse. Image depicts deeper cortical layer marker TBR1, layer VI (green), and phalloidin staining in the coronal sections of the lateral ventricle wall in (a) Wt (Diap1+/+) and (b) mutant (Diap1−/−) mice at E14.5 day. Boxed areas are shown at the higher magnification. Scale bars 200 μm at lower magnification and 50 μm at higher magnification. (c–d) Nissl staining of coronal brain sections of Diap1-KO and Wt at P0. Note the lateral ventricle dilatation on the Diap1-KO mouse. Scale bar is 1 mm.

Given that mDia1 nucleates and processively elongates linear actin filaments20 and that the actin cytoskeleton has a critical role in the regulation of adherence junctions in the neuroepithelium, we also stained tissue sections of mice using fluorescently labeled phalloidin and immunofluorescence with antibodies against other adherent junction components such as β-catenin (CTNNB1), N-cadherin (CDH2), and E-cadherin (CDH1). We found that actin filaments smoothly lined the apical surface of neuroepithelial progenitor cells in wild-type and Diap1−/− mice (Figure 4b and Supplementary Figure 8, upper panel). Our result showed that, in contrast to the requirement for both mDia1 and mDia3, as revealed by analysis of Diaph1/2-DKO, loss of mDia1 alone does not affect the assembly of the apical actin belt at the apical surface of neuroepithelial cells as well as the adhesion molecules in the adherens junctions. mDia1 and other formins also modulate the microtubule (MT) cytoskeleton.21, 22 We investigated α-tubulin and γ-tubulin expression in Diap1−/− animals at E14.5. The absence of DIAPH1 did not grossly alter the organization of tubulin in coronal sections of the lateral vertical wall (Supplementary Figure 8, middle and lower panels).

Prior study of Diap1/2-null, but not Diap1-null, mice revealed impaired tangential migration of cortical and olfactory interneurons compared with either wild-type or Diap2-mutant mice at E16.5.4 Our analysis of Diap1−/− mice did not reveal any obvious alterations in the distribution of GABA-containing interneurons in the cortex (Supplementary Figure 9).

Given that affected human individuals exhibit hypoplasia of the corpus callosum, we analyzed Diap1−/− animals for changes in callosal thickness. Comparison between Diap1−/− and wild-type littermates at P0 revealed no significant differences in cortical white matter or callosal thickness (Supplementary Figure 10). Together, these findings indicate that loss of function of Diap1 in mice, unlike in humans, does not lead to MCP or callosal hypoplasia.

Discussion

We have identified a new human MCP gene, DIAPH1, in a consanguineous family with syndromic congenital MCP, blindness, seizures, developmental delay, ID, and short stature. mRNA and protein expression studies confirm that, similar to other MCP genes, DIAPH1 is expressed in neural progenitors where it is associated with the centrosomes and mitotic spindle. Specifically, expression was found within VZ and SVZ zones of the developing cerebral wall. The centrosome is an organelle that has multiple critical roles in the organization of the mitotic spindle and the astral microtubules during mitosis and in neuronal migration to the cortical plate. Similar to most MCP genes that encode proteins that localize to the centrosome or mitotic spindle, the DIAPH1 gene product mDia1 showed perinuclear localization, which was concentrated on mitotic spindles and co-localized with centrosomes in the M phase of hNPCs at mitotic division. Hence, the expression pattern of DIAPH1 in the brain was consistent with a role in neurogenesis and in regulation of the size of the cerebral cortex. Moreover, previously it has been reported that both ARP2/3- and mDia1-dependent actin polymerization is required for centrosome separation in early Drosophila embryos23 and that DIAPH1 localizes to the spindle microtubules of non-neuronal cells during mitotic cell division.24

The SAR1008 pedigree described here presented with MCP and growth retardations, sharing features with other syndromal microcephalies, including Seckel syndrome (MIM 210600)25 and MOPD II (MIM 210720).26 Consistent with our current findings, another centrosomal protein, PCNT, leads to Seckel and MOPD II syndrome and has been shown necessary for efficient recruitment of Cdk5rap2 to the centrosome in neural progenitors.27 As noted, our co-expression analysis using known MCP genes identified a link between DIAPH1 and CDK5RAP2 that is associated with centrosomal function and mitotic spindle orientation. CDK5RAP2 localizes at the centrosome during mitosis and interacts directly with microtubule-end binding protein (EB1) to regulate microtubule dynamics and stability.28 Interestingly, EB1 and adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) interact with the FH1 and FH2 domains of DIAPH1 to stabilize microtubules and promote cell migration.29 This evidence supports a model in which different MCP genes converge on the same mechanism.

Although animal models have been quite useful for illuminating cellular and molecular mechanisms of MCP, so far few have faithfully and consistently recapitulated the human phenotype. For example, the mouse model for Aspm, which was represented by two mouse lines (Aspm1–25 and Aspm1–7), identified only mild reductions in brain size in Aspm1–7, and no significant difference in brain size in Aspm1–25.30 Similarly, a single study identified no significant difference between Wt and KO-Mcph1 mice,31 whereas a second group showed that Mcph1 disruption in mice resulted in MCP.32 In contrast, the mouse model of Cdk5rap2 shows dramatic reductions in brain size along with other brain phenotypes, including enlarged ventricles.33

In this case, Diap1 knockouts do not recapitulate a small brain phenotype or callosal hypoplasia, but similar to Cdk5rap2 show enlarged ventricles. These species differences may result from the molecular and cellular differences in how the cerebral cortex develops in the two species. Some of the most prominent features of cortical neurogenesis in humans, when compared with mice, are the prolonged neurogenesis,34 the elongation of the apical fiber of radial glial cells (RGCs),35 and the enlargement of the outer SVZ zone and outer RGCs.36, 37 However, the most striking structural finding in Diap1 KO mice was unilateral ventricular enlargement (9 out of 15). Consistent with these findings, a variable degree of ventricular enlargement has been reported as an MCP-related brain malformation in both mice and humans.33, 38

Recent published data from mouse KO models or non-neuronal tumor cell lines in vitro suggest that mDia1 is a Rho-effector and has a critical role in the maintenance of the adherens junction and polarity of neuroepithelial cells in multiple brain regions and in shaping F-actin dynamics that drives tangential migration of neuronal precursors.4, 19, 39 Even though radial migration was promoted and tangential migration was impaired in neuronal precursors from Diaph1/2-DKO mice, this migration deficit is more apparent for those migrating a longer distance of tangential migration by regulating movement of F-actin condensation at the leading edge and formation of an F-actin cup at the rear edge of SVZ neural progenitor cells. Hence, the maximum distance between centrosome and nucleus before nuclear translocation was significantly reduced.4

Together, our genetic and molecular biological data, coupled with previous findings, provide strong evidence that mDia1 has a crucial role in brain development, leads to MCP in humans and exhibits species differences in its function in the developing nervous system.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH grants; Clinical Investigation and the Clinical and Translational Science (UL1 TR000142 and KL2 TR000140) from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the NIH, and NIH roadmap for Medical Research (PI; Robert Sherwin), NS054273, MH081896 (PI; Nenad Sestan) and the Overlook International Foundation (to MWS). ASA is grateful to the Jay and Betty Van Andel endowment and to Ms Susan Kitchen-Goosen for Diap1 mutant mouse management. We thank the families for their participation and AO Caglayan and Y Cheng (from M. Gunel Lab) for technical assistance.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on European Journal of Human Genetics website (http://www.nature.com/ejhg)

Supplementary Material

References

- Abuelo D. Microcephaly syndromes. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2007;14:118–127. doi: 10.1016/j.spen.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilguvar K, Ozturk AK, Louvi A, et al. Whole-exome sequencing identifies recessive WDR62 mutations in severe brain malformations. Nature. 2010;467:207–210. doi: 10.1038/nature09327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton GK, Woods CG. Primary microcephaly: do all roads lead to Rome. Trends Genet. 2009;25:501–510. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2009.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinohara R, Thumkeo D, Kamijo H, et al. A role for mDia, a Rho-regulated actin nucleator, in tangential migration of interneuron precursors. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:S371–S372. doi: 10.1038/nn.3020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch ED, Lee MK, Morrow JE, Welcsh PL, Leon PE, King MC. Nonsyndromic deafness DFNA1 associated with mutation of a human homolog of the Drosophila gene diaphanous. Science. 1997;278:1315–1318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenmann KM, Dykema KJ, Matheson SF, et al. 5q- myelodysplastic syndromes: chromosome 5q genes direct a tumor-suppression network sensing actin dynamics. Oncogene. 2009;28:3429–3441. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tominaga T, Sahai E, Chardin P, McCormick F, Courtneidge SA, Alberts AS. Diaphanous-related formins bridge Rho GTPase and Src tyrosine kinase signaling. Mol Cell. 2000;5:13–25. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80399-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu TW, Mochida GH, Tischfield DJ, et al. Mutations in WDR62, encoding a centrosome-associated protein, cause microcephaly with simplified gyri and abnormal cortical architecture. Nat Genet. 2010;42:1015–1020. doi: 10.1038/ng.683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas AK, Khurshid M, Desir J, et al. WDR62 is associated with the spindle pole and is mutated in human microcephaly. Nat Genet. 2010;42:1010–1014. doi: 10.1038/ng.682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond J, Roberts E, Springell K, et al. A centrosomal mechanism involving CDK5RAP2 and CENPJ controls brain size. Nat Genet. 2005;37:353–355. doi: 10.1038/ng1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guernsey DL, Jiang H, Hussin J, et al. Mutations in centrosomal protein CEP152 in primary microcephaly families linked to MCPH4. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;87:40–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond J, Scott S, Hampshire DJ, et al. Protein-truncating mutations in ASPM cause variable reduction in brain size. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73:1170–1177. doi: 10.1086/379085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain MS, Baig SM, Neumann S, et al. A truncating mutation of CEP135 causes primary microcephaly and disturbed centrosomal function. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90:871–878. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang HJ, Kawasawa YI, Cheng F, et al. Spatio-temporal transcriptome of the human brain. Nature. 2011;478:483–489. doi: 10.1038/nature10523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smoot ME, Ono K, Ruscheinski J, Wang PL, Ideker T. Cytoscape 2.8: new features for data integration and network visualization. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:431–432. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng J, Wallar BJ, Flanders A, Swiatek PJ, Alberts AS. Disruption of the Diaphanous-related formin Drf1 gene encoding mDia1 reveals a role for Drf3 as an effector for Cdc42. Curr Biol. 2003;13:534–545. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00170-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thumkeo D, Shinohara R, Watanabe K, et al. Deficiency of mDia, an actin nucleator, disrupts integrity of neuroepithelium and causes periventricular dysplasia. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25465. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Higgs HN. The mouse Formin mDia1 is a potent actin nucleation factor regulated by autoinhibition. Curr Biol. 2003;13:1335–1340. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00540-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartolini F, Gundersen GG. Formins and microtubules. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1803:164–173. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palazzo A, Ackerman B, Gundersen GG. Cell biology: tubulin acetylation and cell motility. Nature. 2003;421:230. doi: 10.1038/421230a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao J, Crest J, Fasulo B, Sullivan W. Cortical actin dynamics facilitate early-stage centrosome separation. Curr Biol. 2010;20:770–776. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.02.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato T, Watanabe N, Morishima Y, Fujita A, Ishizaki T, Narumiya S. Localization of a mammalian homolog of diaphanous, mDia1, to the mitotic spindle in HeLa cells. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:775–784. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.4.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith E, Walker S, Martin CA, et al. Mutations in pericentrin cause Seckel syndrome with defective ATR-dependent DNA damage signaling. Nat Genet. 2008;40:232–236. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauch A, Thiel CT, Schindler D, et al. Mutations in the pericentrin (PCNT) gene cause primordial dwarfism. Science. 2008;319:816–819. doi: 10.1126/science.1151174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchman JJ, Tseng HC, Zhou Y, Frank CL, Xie Z, Tsai LH. Cdk5rap2 interacts with pericentrin to maintain the neural progenitor pool in the developing neocortex. Neuron. 2010;66:386–402. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong KW, Hau SY, Kho YS, Jia Y, He L, Qi RZ. Interaction of CDK5RAP2 with EB1 to track growing microtubule tips and to regulate microtubule dynamics. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:3660–3670. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-01-0009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen Y, Eng CH, Schmoranzer J, et al. EB1 and APC bind to mDia to stabilize microtubules downstream of Rho and promote cell migration. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:820–830. doi: 10.1038/ncb1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulvers JN, Bryk J, Fish JL, et al. Mutations in mouse Aspm (abnormal spindle-like microcephaly associated) cause not only microcephaly but also major defects in the germline. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:16595–16600. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010494107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trimborn M, Ghani M, Walther DJ, et al. Establishment of a mouse model with misregulated chromosome condensation due to defective Mcph1 function. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9242. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber R, Zhou Z, Sukchev M, Joerss T, Frappart PO, Wang ZQ. MCPH1 regulates the neuroprogenitor division mode by coupling the centrosomal cycle with mitotic entry through the Chk1-Cdc25 pathway. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:1325–1334. doi: 10.1038/ncb2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lizarraga SB, Margossian SP, Harris MH, et al. Cdk5rap2 regulates centrosome function and chromosome segregation in neuronal progenitors. Development. 2010;137:1907–1917. doi: 10.1242/dev.040410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charvet CJ, Finlay BL. Embracing covariation in brain evolution: large brains, extended development, and flexible primate social systems. Prog Brain Res. 2012;195:71–87. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-53860-4.00004-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakic P. Evolution of the neocortex: a perspective from developmental biology. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:724–735. doi: 10.1038/nrn2719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy H, Dehay C. Self-organization and interareal networks in the primate cortex. Prog Brain Res. 2012;195:341–360. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-53860-4.00016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lui JH, Hansen DV, Kriegstein AR. Development and evolution of the human neocortex. Cell. 2011;146:18–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passemard S, Titomanlio L, Elmaleh M, et al. Expanding the clinical and neuroradiologic phenotype of primary microcephaly due to ASPM mutations. Neurology. 2009;73:962–969. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181b8799a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaoui K, Honore S, Isnardon D, Braguer D, Badache A. Memo-RhoA-mDia1 signaling controls microtubules, the actin network, and adhesion site formation in migrating cells. J Cell Biol. 2008;183:401–408. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200805107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.