Abstract

It is now well established that reactive oxygen species (ROS), reactive nitrogen species (RNS), and a basal level of oxidative stress are essential for cell survival. It is also well known that while severe oxidative stress often leads to widespread oxidative damage and cell death, a moderate level of oxidative stress, induced by a variety of stressors, can yield great beneficial effects on adaptive cellular responses to pathological challenges in aging and aging-associated disease tolerance such as ischemia tolerance. Here in this review, I term this moderate level of oxidative stress as positive oxidative stress, which usually involves imprinting molecular signatures on lipids and proteins via formation of lipid peroxidation by-products and protein oxidation adducts. As ROS/RNS are short-lived molecules, these molecular signatures can thus execute the ultimate function of ROS/RNS. Representative examples of lipid peroxidation products and protein oxidation adducts are presented to illustrate the role of positive oxidative stress in a variety of pathological settings, demonstrating that positive oxidative stress could be a valuable prophylactic and/or therapeutic approach targeting aging and aging-associated diseases.

Keywords: Aging, Reactive oxygen species, Reactive nitrogen species, Disease tolerance, Positive oxidative stress

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Basal levels of ROS and RNS are essential for cell survival.

-

•

Severe oxidative stress and oxidative damage usually lead to cell death.

-

•

Positive oxidative stress can be induced by preconditioning and postconditioning.

-

•

Lipid- and protein oxidation can execute the effects of positive oxidative stress.

-

•

Positive oxidative stress can serve as a prophylactic or therapeutic approach.

Introduction

Production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) is part of normal aerobic cellular metabolism [1–5]. While RNS generally originate from nitric oxide synthases, ROS can be generated by a variety of enzymes and metabolic pathways, including mitochondrial complexes I–III [6–9] in the electron transport chain, dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase in the α-keto acid dehydrogenase complexes [10–14], NADPH oxidase [15,16], xanthine oxidase [17,18], monoamine oxidase [19], and cytochrome P450 proteins [20]. All of these systems may result in oxidative stress under appropriate conditions. Although basal levels of ROS/RNS are indispensible for redox signaling and cell survival [21,22], high levels of ROS/RNS would be detrimental to cells and have been thought to contribute to aging and the pathogenesis of numerous aging-related diseases [22,23]. On the other hand, a moderate level of oxidative stress, reflected by a moderate level of ROS/RNS production, could be induced and modulated to produce an adaptive cellular response that is beneficial for cell survival [22–27].

Oxidative stress is a situation whereby cellular levels of ROS or RNS overwhelm the cellular antioxidant capacities [20]. This condition, when severe, usually leads to extensive modifications or damage to macromolecules including DNA, lipids and proteins [28,29]. Collectively, these damaged macromolecules, when beyond the cell′s reparative and degradative activities, can eventually induce cell death and tissue injury [22,25]. Nonetheless, increasing evidence has now established that many protein oxidation or lipid oxidation products can be beneficial for cell survival [29–32]. These oxidation products are usually caused by a moderate level of oxidative stress, which is termed here as positive oxidative stress. This is the type of oxidative stress that can induce or is part of an adaptive response that protects cells against subsequent severe challenges that otherwise would trigger widespread oxidative damage and cell death [23,27].

In order to create a positive oxidative stress condition, it is necessary to stress cells with a stressor [22,27]. Many stressors, when used at appropriate dosages, can elicit a moderate or non-lethal level of oxidative stress in the absence of cytotoxicity and cell death [27]. Nonetheless, it should be pointed out that if used at higher dosages; almost all stressors will inevitably yield toxicity that leads to cell death.

The best examples of positive oxidative stress would be ischemic tolerance including preconditioning and postconditioning, which are clinically-relevant approaches applied in a variety of animal models for protection of tissues against ischemia-induced injuries [33–35]. It has been well-demonstrated that a variety of stressors, such as, mitochondrial electron transport chain inhibitors [36], hypoxia [37], hyperoxia [38,39], hyperthermia [40] and hypothermia [41], as well as short episodes of ischemia [42] can induce positive oxidative stress via a transiently increased ROS production that is involved in an adaptive response for prophylactic purposes (Table 1) [43–49]. Accordingly, many studies have shown that antioxidants administered prior to or at the onset of preconditioning or postconditioning induction, can abolish the preconditioning or postconditioning effect [34,35,50,51], thus demonstrating that ROS and oxidative stress are essential for preconditioning or postconditioning to take effect [52–54]. Interestingly, the effects of preconditioning and postconditioning are only evident in severe pathological challenges such as an extended period of ischemia or reperfusion.

Table 1.

Popular stressors known to induce positive oxidative stress. Many of these stressors have been studied in the context of tissue ischemic tolerance.

| Stressors | Beneficial effects | Selected references |

|---|---|---|

| 3-Nitropropionic acid | Complex II inhibitor, ischemic tolerance | [83–85] |

| Rotenone | Complex I inhibitor, ischemic tolerance | [86] |

| Antimycin A | Complex III inhibitor, ischemic tolerance | [86] |

| Diazoxide | kATP channel opener, ischemic tolerance | [87] |

| Cyanide | Complex IV inhibitor, ischemic tolerance | [53] |

| Cobalt chloride | Chemical hypoxia/HIF-1 activation | [88,89] |

| Carbon monoxide | ROS-mediated prevention of apoptosis | [61] |

| Isoflurane | Induction of pre- and postconditioning | [90,91] |

| Short episodes of ischemia | Ischemic tolerance | [92–94] |

| Hypoxia/intermittent hypoxia | Ischemic tolerance | [37,95] |

| Hyperoxia | Ischemic tolerance | [38,39] |

| Hyperthermal stress | Ischemic tolerance | [40] |

| Hypothermal stress | Ischemic tolerance | [41] |

| Remote preconditioning | Ischemic tolerance | [96–98] |

| Physical exercise | Production of beneficial ROS | [50] |

| Hydrogen peroxide | Ischemic tolerance | [99,100] |

| Ozone | Ischemic tolerance | [101,102] |

So how does positive oxidative stress work? As ROS and RNS are short-lived molecules, they themselves cannot impart a persistent beneficial effect [22]. It is thus believed that the targets of ROS and RNS would serve as molecular signatures [23] that relay and extend the beneficial effects of positive oxidative stress [22]. These molecular signatures are those of ROS/RNS modified oxidative products such as lipid peroxidation by-products and protein oxidation adducts. Chemically, numerous protein oxidative modifications involved in positive oxidative stress are reversible such as disulfide formation [55–60], S-glutathionylation [61–64], S-sulfenation [65–67], and S-nitrosylation [68–71]. These enhanced modifications usually play regulatory roles in protein function and thus can elicit great protective effects against cell death induced by a variety of severe stress conditions. As has been reported, all these reversible cysteine modifications can occur under basal conditions [72–79]. In the absence of positive oxidative stress, however, these basal level modifications may have no apparent protective effects owing to their low abundance.

Herein to demonstrate the role of positive oxidative stress in aging and aging-associated diseases, I would like to present a few selected representative examples of oxidative molecular signatures that are beneficial for cell survival. These examples include lipid peroxidation products and protein oxidation adducts.

Positive effect of lipid peroxidation products

Lipid peroxides in hemoglobin-modified low density lipoprotein are beneficial for cell survival

Hemoglobin (Hb) can modify low density lipoproteins (LDL), and lipid oxidation of the latter is usually linked to pathogenesis of atherosclerosis [31]. However, while hemoglobin-binding of LDL renders the complex (Hb–LDL) highly susceptible to lipid peroxidation, such oxidation products are not cytotoxic [31]. The reason for this is that oxidized Hb–LDL could induce HO-1 (hemeoxygenase-1) expression, likely via the activation of the Nrf2 transcription factor [80]. Notably, when oxidized Hb–LDL was reduced by ebselen, HO-1 induction was inhibited [31]. Therefore, oxidized Hb–LDL can exhibit a beneficial effect via HO-1 induction.

Beneficial effect of a cholesterol oxidation product

24-S-hydroxycholesterol (24-SOHC) is endogenously produced in the brain and plays an important role in brain cholesterol homeostasis. Okabe et al. recently showed that 24-SOHS could elicit an adaptive response in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells [81]. They found that cells treated with 24-SOHC at non-lethal levels could significantly attenuate cell death induced subsequently by 7-keto cholesterol (7KC). Furthermore, the attenuation of cell death occurred in both differentiated and non-differentiated cells, and could also be induced by other cholesterol oxidation by-products such as 25-hydroxycholesterol and 27-hydroxycholesterol. Moreover, 24-SOHC treatment upregulated the expression of liver X receptor (LXR) target genes, thereby inducing ATP-binding cassette transporter. When LXRβ was knocked down by siRNA, the adaptive response was greatly diminished. Therefore, 24-SOHC represents another example of positive oxidative stress; which works via transcriptional activation of LXR signaling pathway, leading to neuronal protection against further 7KC-triggered cellular toxicity.

Positive effects of protein oxidation products

Cardioprotection by S-nitrosylation of a single cysteine residue on the mitochondrial complex I subunit ND3

Mammalian mitochondrial complex I has at least 45 subunits and many of them are redox-sensitive proteins that can undergo redox modifications by ROS or RNS [82]. Recently, Chouchani et al. reported that S-nitrosylation of the ND3 subunit within complex I could protect cardiomyocytes against cell death induced by cardiac ischemia reperfusion injury [30]. As this S-nitrosylation occurred on cysteine-39 of ND3 and was induced by a mitochondria-selective S-nitrosylating agent (named mitoSNO) administered at the onset of reperfusion, the authors presented an excellent postconditioning paradigm whereby the nitrosylation of a single cysteine residue can trigger a positive oxidative stress condition that protects against cardiac ischemic injury.

S-cysteine sulfenation of the Parkinson′s disease-associated protein DJ-1 is neuroprotective

Parkinson′s disease (PD) is an age-related neurodegenerative disorder. While it is known that mutations in the gene that encodes DJ-1, a PD-related protein, can abolish neuroprotective function, the underlying mechanisms have been elusive. Madian et al. have recently provided convincing evidence that DJ-1′s protective function in PD is due to the conversion of a cysteine′s sulfhydryl group (–SH) to an S-sulfenation product (–SOH) [32]. The authors further demonstrated that mutations occurring on the DJ-1 gene that disrupted or interfered with this –SH to –SOH conversion on cysteine residue 106 could abolish DJ-1′s neuroprotective function. This study thus provides another example of ROS-induced positive oxidative stress in age-related neurodegenerative disease.

Summary

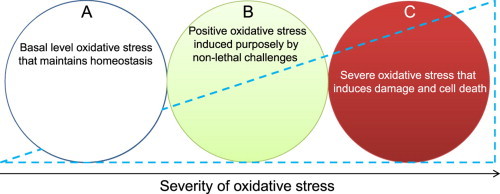

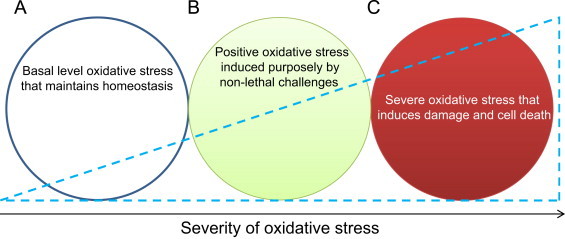

The above representative examples demonstrate that lipid peroxidation by-products and protein oxidation adducts can have tremendous prophylactic effects on aging-related diseases. Fig. 1 shows the relative magnitudes of oxidative stress and the potential corresponding effects. Basically, while a basal level of ROS/RNS and oxidative stress is essential for cell survival [21,22], severe oxidative stress or damage associated with a highly elevated level of ROS/RNS production will inevitably impair the cells′ self-repair ability and thus can lead to cell death [22]. Importantly, a moderate level of oxidative stress, i.e., positive oxidative stress, induced by a moderate level of ROS/RNS, can be triggered by a variety of stressors to protect against further lethal challenges that otherwise would cause cell death and tissue injury [22,23,27].

Fig. 1.

Levels of cellular oxidative stress and their differential effects. (A) basal level oxidative stress that is essential for cell survival and homeostasis; (B) positive oxidative stress that can be induced by a variety of non-lethal challenges that often induce protein oxidative modifications; (C) Severe oxidative stress that induces damage and cell death.

Perspectives

Given that ROS/RNS are short-lived molecules and that the molecular signatures imprinted by these ROS/RNS on lipids and proteins can actually execute the ultimate function of positive oxidative stress, including redox signaling and activation of transcriptional factors [27], further studies will need to be undertaken to identify more targets in a variety of stress settings. Moreover, the underlying mechanisms of such identified targets, especially their prophylactic roles in aging and aging-associated disease tolerance will also need to be elucidated. It is the author′s belief that induction of positive oxidative stress could serve as a valuable prophylactic or therapeutic approach targeting aging and aging-associated diseases.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health (R01NS079792 to L. J. Y.).

Footnotes

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike License, which permits non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

References

- 1.Groeger G., Quiney C., Cotter T.G. Hydrogen peroxide as a cell-survival signaling molecule. Antioxid. Redox Signaling. 2009;11:2655–2671. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knoefler D., Thamsen M., Koniczek M., Niemuth N.J., Diederich A.K., Jakob U. Quantitative in vivo redox sensors uncover oxidative stress as an early event in life. Mol. Cell. 2012;47:767–776. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Groeger G., Doonan F., Cotter T.G., Donovan M. Reactive oxygen species regulate prosurvival ERK1/2 signaling and bFGF expression in gliosis within the retina. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2012;53:6645–6654. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-10525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bevilacqua E., Gomes S.Z., Lorenzon A.R., Hoshida M.S., Amarante-Paffaro A.M. NADPH oxidase as an important source of reactive oxygen species at the mouse maternal-fetal interface: putative biological roles. Reprod. Biomed. Online. 2012;25:31–43. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2012.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watson J. Oxidants, antioxidants and the current incurability of metastatic cancers. Open Biol. 2013;3:120144. doi: 10.1098/rsob.120144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murphy M.P. How mitochondria produce reactive oxygen species. Biochem. J. 2009;417:1–13. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.St-Pierre J., Buckingham J.A., Roebuck S.J., Brand M.D. Topology of superoxide production from different sites in the mitochondrial electron transport chain. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:44784–44790. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207217200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miwa S., St-Pierre J., Partridge L., Brand M.D. Superoxide and hydrogen peroxide production by Drosophila mitochondria. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2003;35:938–948. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00464-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drose S., Brandt U. Molecular mechanisms of superoxide production by the mitochondrial respiratory chain. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2012;748:145–169. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-3573-0_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yan L.J., Thangthaeng N., Sumien N., Forster M.J. Serum dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase is a labile enzyme. J. Biochem. Pharmacol. Res. 2013;1:30–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Starkov A.A., Fiskum G., Chinopoulos C., Lorenzo B.J., Browne S.E., Patel M.S., Beal M.F. Mitochondrial alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex generates reactive oxygen species. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:7779–7788. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1899-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ambrus A., Tretter L., Adam-Vizi V. Inhibition of the alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase-mediated reactive oxygen species generation by lipoic acid. J. Neurochem. 2009;109(Suppl 1):222–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.05942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ambrus A., Torocsik B., Tretter L., Ozohanics O., Adam-Vizi V. Stimulation of reactive oxygen species generation by disease-causing mutations of lipoamide dehydrogenase. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2011;20:2984–2995. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ambrus A., Adam-Vizi V. Molecular dynamics study of the structural basis of dysfunction and the modulation of reactive oxygen species generation by pathogenic mutants of human dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2013;538:145–155. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2013.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manea A. NADPH oxidase-derived reactive oxygen species: involvement in vascular physiology and pathology. Cell Tissue Res. 2010;342:325–339. doi: 10.1007/s00441-010-1060-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bylund J., Brown K.L., Movitz C., Dahlgren C., Karlsson A. Intracellular generation of superoxide by the phagocyte NADPH oxidase: how, where, and what for? Free Radical Biol. Med. 2010;49:1834–1845. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harrison R. Physiological roles of xanthine oxidoreductase. Drug Metab. Rev. 2004;36:363–375. doi: 10.1081/dmr-120037569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Agarwal A., Banerjee A., Banerjee U.C. Xanthine oxidoreductase: a journey from purine metabolism to cardiovascular excitation-contraction coupling. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2011;31:264–280. doi: 10.3109/07388551.2010.527823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cadenas E., Davies K.J. Mitochondrial free radical generation, oxidative stress, and aging. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2000;29:222–230. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00317-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mandelker L. Introduction to oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction. Vet. Clin. North. Am. Small. Anim. Pract. 2008;38:1–30. doi: 10.1016/j.cvsm.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Janssen-Heininger Y.M., Mossman B.T., Heintz N.H., Forman H.J., Kalyanaraman B., Finkel T., Stamler J.S., Rhee S.G., van der Vliet A. Redox-based regulation of signal transduction: principles, pitfalls, and promises. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2008;45:1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sena L.A., Chandel N.S. Physiological roles of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Mol. Cell. 2012;48:158–167. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malinin N.L., West X.Z., Byzova T.V. Oxidation as "the stress of life". Aging (Albany NY) 2011;3:906–910. doi: 10.18632/aging.100385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gorrini C., Harris I.S., Mak T.W. Modulation of oxidative stress as an anticancer strategy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2013;12:931–947. doi: 10.1038/nrd4002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pickering A.M., Vojtovich L., Tower J., KJ A.D. Oxidative stress adaptation with acute, chronic, and repeated stress. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2013;55:109–118. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davies K.J. Oxidative stress, antioxidant defenses, and damage removal, repair, and replacement systems. IUBMB Life. 2000;50:279–289. doi: 10.1080/713803728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Milisav I., Poljsak B., Suput D. Adaptive response, evidence of cross-resistance and its potential clinical use. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012;13:10771–10806. doi: 10.3390/ijms130910771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ames B.N., Shigenaga M.K. Oxidants are a major contributor to aging. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1992;663:85–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb38652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cai Z., Yan L.J. Protein oxidative modifications: beneficial roles in disease and health. J. Biochem. Pharmacol. Res. 2013;1:15–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chouchani E.T., Methner C., Nadtochiy S.M., Logan A., Pell V.R., Ding S., James A.M., Cocheme H.M., Reinhold J., Lilley K.S., Partridge L., Fearnley I.M., Robinson A.J., Hartley R.C., Smith R.A., Krieg T., Brookes P.S., Murphy M.P. Cardioprotection by S-nitrosation of a cysteine switch on mitochondrial complex I. Nat. Med. 2013;19:753–759. doi: 10.1038/nm.3212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Asatryan L., Ziouzenkova O., Duncan R., Sevanian A. Heme and lipid peroxides in hemoglobin-modified low-density lipoprotein mediate cell survival and adaptation to oxidative stress. Blood. 2003;102:1732–1739. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-01-0293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Madian A.G., Hindupur J., Hulleman J.D., Diaz-Maldonado N., Mishra V.R., Guigard E., Kay C.M., Rochet J.C., Regnier F.E. Effect of single amino acid substitution on oxidative modifications of the Parkinson′s disease-related protein, DJ-1. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2012;11:010892. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.010892. (M111) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bosetti F., Yu G., Zucchi R., Ronca-Testoni S., Solaini G. Myocardial ischemic preconditioning and mitochondrial F1F0-ATPase activity. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2000;215:31–37. doi: 10.1023/a:1026558922596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mori T., Muramatsu H., Matsui T., McKee A., Asano T. Possible role of the superoxide anion in the development of neuronal tolerance following ischaemic preconditioning in rats. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 2000;26:31–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2990.2000.00215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ristow M., Schmeisser S. Extending life span by increasing oxidative stress. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2011;51:327–336. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wiegand F., Liao W., Busch C., Castell S., Knapp F., Lindauer U., Megow D., Meisel A., Redetzky A., Ruscher K., Trendelenburg G., Victorov I., Riepe M., Diener H.C., Dirnagl U. Respiratory chain inhibition induces tolerance to focal cerebral ischemia. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1999;19:1229–1237. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199911000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stowe A.M., Altay T., Freie A.B., Gidday J.M. Repetitive hypoxia extends endogenous neurovascular protection for stroke. Ann. Neurol. 2011;69:975–985. doi: 10.1002/ana.22367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bigdeli M.R. Neuroprotection caused by hyperoxia preconditioning in animal stroke models. Sci. World J. 2011;11:403–421. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2011.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Soejima Y., Hu Q., Krafft P.R., Fujii M., Tang J., Zhang J.H. Hyperbaric oxygen preconditioning attenuates hyperglycemia-enhanced hemorrhagic transformation by inhibiting matrix metalloproteinases in focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Exp. Neurol. 2013;247:737–743. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2013.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Duveau V., Arthaud S., Serre H., Rougier A., Le Gal La Salle G. Transient hyperthermia protects against subsequent seizures and epilepsy-induced cell damage in the rat. Neurobiol. Dis. 2005;19:142–149. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zieger M.A., Gupta M.P. Hypothermic preconditioning of endothelial cells attenuates cold-induced injury by a ferritin-dependent process. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2009;46:680–691. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Blanco M., Lizasoain I., Sobrino T., Vivancos J., Castillo J. Ischemic preconditioning: a novel target for neuroprotective therapy. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2006;21(Suppl. 2):38–47. doi: 10.1159/000091702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bhagatte Y., Lodwick D., Storey N. Mitochondrial ROS production and subsequent ERK phosphorylation are necessary for temperature preconditioning of isolated ventricular myocytes. Cell Death Dis. 2012;3:e345. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2012.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vanden Hoek T.L., Becker L.B., Shao Z., Li C., Schumacker P.T. Reactive oxygen species released from mitochondria during brief hypoxia induce preconditioning in cardiomyocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:18092–18098. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.29.18092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Costa V.M., Silva R., Ferreira R., Amado F., Carvalho F., de Lourdes Bastos M., Carvalho R.A., Carvalho M., Remiao F. Adrenaline in pro-oxidant conditions elicits intracellular survival pathways in isolated rat cardiomyocytes. Toxicology. 2009;257:70–79. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Penna C., Mancardi D., Rastaldo R., Pagliaro P. Cardioprotection: a radical view Free radicals in pre and postconditioning. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009;1787:781–793. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tejima K., Arai M., Ikeda H., Tomiya T., Yanase M., Inoue Y., Nagashima K., Nishikawa T., Watanabe N., Omata M., Fujiwara K. Ischemic preconditioning protects hepatocytes via reactive oxygen species derived from Kupffer cells in rats. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1488–1496. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Facundo H.T., Carreira R.S., de Paula J.G., Santos C.C., Ferranti R., Laurindo F.R., Kowaltowski A.J. Ischemic preconditioning requires increases in reactive oxygen release independent of mitochondrial K+ channel activity. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2006;40:469–479. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim J., Jang H.S., Park K.M. Reactive oxygen species generated by renal ischemia and reperfusion trigger protection against subsequent renal ischemia and reperfusion injury in mice. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2010;298:F158–F166. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00474.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ristow M., Zarse K., Oberbach A., Kloting N., Birringer M., Kiehntopf M., Stumvoll M., Kahn C.R., Bluher M. Antioxidants prevent health-promoting effects of physical exercise in humans. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009;106:8665–8670. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903485106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fernandez V., Tapia G., Varela P., Cornejo P., Videla L.A. Upregulation of liver inducible nitric oxide synthase following thyroid hormone preconditioning: suppression by N-acetylcysteine. Biol. Res. 2009;42:487–495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fernandez V., Tapia G., Varela P., Gaete L., Vera G., Mora C., Vial M.T., Videla L.A. Causal role of oxidative stress in liver preconditioning by thyroid hormone in rats. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2008;44:1724–1731. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Correia S.C., Santos R.X., Cardoso S.M., Santos M.S., Oliveira C.R., Moreira P.I. Cyanide preconditioning protects brain endothelial and NT2 neuron-like cells against glucotoxicity: role of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and HIF-1alpha. Neurobiol. Dis. 2012;45:206–218. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Salie R., Moolman J.A., Lochner A. The mechanism of beta-adrenergic preconditioning: roles for adenosine and ROS during triggering and mediation. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2012;107:281. doi: 10.1007/s00395-012-0281-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.O′Brian C.A., Chu F. Post-translational disulfide modifications in cell signaling—role of inter-protein, intra-protein, S-glutathionyl, and S-cysteaminyl disulfide modifications in signal transmission. Free Radical Res. 2005;39:471–480. doi: 10.1080/10715760500073931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ghezzi P., Bonetto V., Fratelli M. Thiol-disulfide balance: from the concept of oxidative stress to that of redox regulation. Antioxid. Redox Signaling. 2005;7:964–972. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shimizu Y., Hendershot L.M. Oxidative folding: cellular strategies for dealing with the resultant equimolar production of reactive oxygen species. Antioxid. Redox Signaling. 2009;11:2317–2331. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Guo Z., Kozlov S., Lavin M.F., Person M.D., Paull T.T. ATM activation by oxidative stress. Science. 2010;330:517–521. doi: 10.1126/science.1192912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li W., Zhang J., An W. The conserved CXXC motif of hepatic stimulator substance is essential for its role in mitochondrial protection in H2O2-induced cell apoptosis. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:3929–3935. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.P.C. Wei, Y.H. Hsieh, M.I. Su, X.J. Jiang, P.H. Hsu, W.T. Lo, J.Y. Weng, Y.M. Jeng, J.M. Wang, P.L. Chen, Y.C. Chang, K.F. Lee, M.D. Tsai, J.Y. Shew, W.H. Lee, Loss of the oxidative stress sensor NPGPx compromises GRP78 chaperone activity and induces systemic disease, Mol. Cell (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 61.Queiroga C.S., Almeida A.S., Martel C., Brenner C., Alves P.M., Vieira H.L. Glutathionylation of adenine nucleotide translocase induced by carbon monoxide prevents mitochondrial membrane permeabilization and apoptosis. J, Biol, Chem. 2010;285:17077–17088. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.065052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xiong Y., Uys J.D., Tew K.D., Townsend D.M. S-Glutathionylation: from molecular mechanisms to health outcomes. Antioxid. Redox Signaling. 2011;15:233–270. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pastore A., Piemonte F. S-Glutathionylation signaling in cell biology: progress and prospects. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2012;46:279–292. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pimentel D., Haeussler D.J., Matsui R., Burgoyne J.R., Cohen R.A., Bachschmid M.M. Regulation of cell physiology and pathology by protein S-glutathionylation: lessons learned from the cardiovascular system. Antioxid. Redox Signaling. 2012;16:524–542. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kaiserova K., Srivastava S., Hoetker J.D., Awe S.O., Tang X.L., Cai J., Bhatnagar A. Redox activation of aldose reductase in the ischemic heart. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:15110–15120. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600837200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kaiserova K., Tang X.L., Srivastava S., Bhatnagar A. Role of nitric oxide in regulating aldose reductase activation in the ischemic heart. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:9101–9112. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709671200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wetzelberger K., Baba S.P., Thirunavukkarasu M., Ho Y.S., Maulik N., Barski O.A., Conklin D.J., Bhatnagar A. Postischemic deactivation of cardiac aldose reductase: role of glutathione S-transferase P and glutaredoxin in regeneration of reduced thiols from sulfenic acids. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:26135–26148. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.146423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li F., Sonveaux P., Rabbani Z.N., Liu S., Yan B., Huang Q., Vujaskovic Z., Dewhirst M.W., Li C.Y. Regulation of HIF-1alpha stability through S-nitrosylation. Mol. Cell. 2007;26:63–74. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yan L.J., Liu L., Forster M.J. Reversible inactivation of dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase by Angeli′s salt. Acta Biophys. Sin. (Sheng Wu Wu Li Hsueh Bao) 2012;28:341–350. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Foster M.W., Hess D.T., Stamler J.S. Protein S-nitrosylation in health and disease: a current perspective. Trends Mol. Med. 2009;15:391–404. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Haldar S.M., Stamler J.S. S-nitrosylation: integrator of cardiovascular performance and oxygen delivery. J. Clin. Invest. 2013;123:101–110. doi: 10.1172/JCI62854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jacob C., Battaglia E., Burkholz T., Peng D., Bagrel D., Montenarh M. Control of oxidative posttranslational cysteine modifications: from intricate chemistry to widespread biological and medical applications. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2012;25:588–604. doi: 10.1021/tx200342b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pastore A., Piemonte F. Protein glutathionylation in cardiovascular diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013;14:20845–20876. doi: 10.3390/ijms141020845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Go Y.M., Jones D.P. Thiol/disulfide redox states in signaling and sensing. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2013;48:173–181. doi: 10.3109/10409238.2013.764840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yan L.J., Sumien N., Thangthaeng N., Forster M.J. Reversible inactivation of dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase by mitochondrial hydrogen peroxide. Free Radical Res. 2013;47:123–133. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2012.752078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cremers C.M., Jakob U. Oxidant sensing by reversible disulfide bond formation. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:26489–26496. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R113.462929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Brennan J.P., Wait R., Begum S., Bell J.R., Dunn M.J., Eaton P. Detection and mapping of widespread intermolecular protein disulfide formation during cardiac oxidative stress using proteomics with diagonal electrophoresis. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:41352–41360. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403827200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kettenhofen N.J., Wood M.J. Formation, reactivity, and detection of protein sulfenic acids. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2010;23:1633–1646. doi: 10.1021/tx100237w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sun J., Murphy E. Protein S-nitrosylation and cardioprotection. Circ. Res. 2010;106:285–296. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.209452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Surh Y.J., Kundu J.K., Li M.H., Na H.K., Cha Y.N. Role of Nrf2-mediated heme oxygenase-1 upregulation in adaptive survival response to nitrosative stress. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2009;32:1163–1176. doi: 10.1007/s12272-009-1807-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Okabe A., Urano Y., Itoh S., Suda N., Kotani R., Nishimura Y., Saito Y., Noguchi N. Adaptive responses induced by 24S-hydroxycholesterol through liver X receptor pathway reduce 7-ketocholesterol-caused neuronal cell death. Redox Biol. 2014;2:28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2013.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hirst J. Mitochondrial complex I. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2013;82:551–575. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-070511-103700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Brambrink A.M., Schneider A., Noga H., Astheimer A., Gotz B., Korner I., Heimann A., Welschof M., Kempski O. Tolerance-Inducing dose of 3-nitropropionic acid modulates bcl-2 and bax balance in the rat brain: a potential mechanism of chemical preconditioning. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2000;20:1425–1436. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200010000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hoshi A., Nakahara T., Ogata M., Yamamoto T. The critical threshold of 3-nitropropionic acid-induced ischemic tolerance in the rat. Brain Res. 2005;1050:33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Klivenyi P., Starkov A.A., Calingasan N.Y., Gardian G., Browne S.E., Yang L., Bubber P., Gibson G.E., Patel M.S., Beal M.F. Mice deficient in dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase show increased vulnerability to MPTP, malonate and 3-nitropropionic acid neurotoxicity. J. Neurochem. 2004;88:1352–1360. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Carriere A., Ebrahimian T.G., Dehez S., Auge N., Joffre C., Andre M., Arnal S., Duriez M., Barreau C., Arnaud E., Fernandez Y., Planat-Benard V., Levy B., Penicaud L., Silvestre J.S., Casteilla L. Preconditioning by mitochondrial reactive oxygen species improves the proangiogenic potential of adipose-derived cells-based therapy. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2009;29:1093–1099. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.188318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hanley P.J., Daut J. K(ATP) channels and preconditioning: a re-examination of the role of mitochondrial K(ATP) channels and an overview of alternative mechanisms. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2005;39:17–50. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kim E.J., Yoo Y.G., Yang W.K., Lim Y.S., Na T.Y., Lee I.K., Lee M.O. Transcriptional activation of HIF-1 by RORalpha and its role in hypoxia signaling. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2008;28:1796–1802. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.171546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Jones S.M., Novak A.E., Elliott J.P. The role of HIF in cobalt-induced ischemic tolerance. Neuroscience. 2013;252:420–430. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.07.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.McMurtrey R.J., Zuo Z. Isoflurane preconditioning and postconditioning in rat hippocampal neurons. Brain Res. 2010;1358:184–190. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sun X., Sun J., Liu L., Ding Z. Isoflurane preconditioning and postconditioning in multiple organ protection. J. Biochem. Pharmacol. Res. 2013;1:6–14. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zhan R.Z., Fujihara H., Baba H., Yamakura T., Shimoji K. Ischemic preconditioning is capable of inducing mitochondrial tolerance in the rat brain. Anesthesiology. 2002;97:896–901. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200210000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Eaton P., Bell R.M., Cave A.C., Shattock M.J. Ischemic preconditioning: a potential role for protein S-thiolation? Antioxid. Redox Signaling. 2005;7:882–888. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hausenloy D.J., Wynne A.M., Yellon D.M. Ischemic preconditioning targets the reperfusion phase. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2007;102:445–452. doi: 10.1007/s00395-007-0656-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Stowe A.M., Wacker B.K., Cravens P.D., Perfater J.L., Li M.K., Hu R., Freie A.B., Stuve O., Gidday J.M. CCL2 upregulation triggers hypoxic preconditioning-induced protection from stroke. J. Neuroinflammation. 2012;9:33. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-9-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Schmidt M.R., Kristiansen S.B., Botker H.E. Remote ischemic preconditioning: no loss in clinical translation. Circ. Res. 2013;113:1278–1280. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.302942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kristiansen S.B., Henning O., Kharbanda R.K., Nielsen-Kudsk J.E., Schmidt M.R., Redington A.N., Nielsen T.T., Botker H.E. Remote preconditioning reduces ischemic injury in the explanted heart by a KATP channel-dependent mechanism. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2005;288:H1252–H1256. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00207.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Zhao H., Ren C., Chen X., Shen J. From rapid to delayed and remote postconditioning: the evolving concept of ischemic postconditioning in brain ischemia. Curr. Drug Targets. 2012;13:173–187. doi: 10.2174/138945012799201621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Geracitano R., Tozzi A., Berretta N., Florenzano F., Guatteo E., Viscomi M.T., Chiolo B., Molinari M., Bernardi G., Mercuri N.B. Protective role of hydrogen peroxide in oxygen-deprived dopaminergic neurones of the rat substantia nigra. J. Physiol. 2005;568:97–110. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.092510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Pendergrass K.D., Boopathy A.V., Seshadri G., Maiellaro-Rafferty K., Che P.L., Brown M.E., Davis M.E. Acute preconditioning of cardiac progenitor cells with hydrogen peroxide enhances angiogenic pathways following ischemia-reperfusion injury. Stem Cells Dev. 2013;22:2414–2424. doi: 10.1089/scd.2012.0673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ahmed L.A., Salem H.A., Mawsouf M.N., Attia A.S., Agha A.M. Cardioprotective effects of ozone oxidative preconditioning in an in vivo model of ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Invest. 2012;72:345–354. doi: 10.3109/00365513.2012.663100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Chen H., Xing B., Liu X., Zhan B., Zhou J., Zhu H., Chen Z. Ozone oxidative preconditioning inhibits inflammation and apoptosis in a rat model of renal ischemia/reperfusion injury. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2008;581:306–314. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]