Abstract

E learning means use of electronic media and information technologies in education. Virtual learning environment (VLE) provides learning platforms consisting of online tools, databases and managed resources. This article is a review of use of E learning in medical and surgical education including available evidence favouring this approach. E learning has been shown to be more effective, less costly and more satisfying to the students than the traditional methods. E learning cannot however replace direct consultant supervision at their place of work in surgical trainees and a combination of both called blended learning has been shown to be most useful. As an example of university-based qualification, one such programme is presented to clarify the components and the process of E learning. Increasing use of E learning and occasional face to face focussed supervision by the teacher is likely to enhance surgical training in the future.

Keywords: E learning, Surgery, Education, VLE

Introduction

E learning means use of electronic media and information technologies in education. Other terms such as computer-based training, internet-based training, web-based training, on line education and virtual education are also used. Virtual learning environment (VLE) provides learning platforms consisting of online tools, databases and managed resources functioning collectively in support of education.

The Open University of Britain [1] and University of British Columbia [2] were the first to begin the use of the internet to deliver learning using web-based training, on line distance learning and online student discussion [3]. Exploiting the advent of the World Wide Web in the 1990s on line courses have been growing each year both in medicine and other areas of education. The council of Europe has passed a statement endorsing e learning to drive equality and improvement of education across the European Union (EU) [4].

This article is a review of use of e learning in health and medicine and available evidence. As an example of university-based qualification, one programme is described here to illustrate the components and process of e learning in surgery.

E Learning in Undergraduate Medical Education

The University of British Columbia Faculty Of Medicine, Vancouver, Canada has been providing Medicine and Dentistry Integrated Curriculum Online (MEDICOL) programme using a variety of web-based resources in their medical and dental undergraduate curriculum. Their course-management system provided the following educational functions:

Track students’ progress and present course information such as timetables, learning objectives, handout materials, images, references, course assignments and evaluations

Promote student-to-student and student-to-instructor interactions (through e-mail and bulletin boards)

Deliver self-directed learning components, including weekly self-assessment quizzes that provide immediate feedback and multimedia learning modules

More than 90 % of the students used these online resources and found them useful [5].

During clinical rotations, the student placements may be at hospital locations distant from the main academic campus. This can be addressed by distance learning environments. One such example is at Midwestern University, Glendale, Arizona, USA. They implemented web-based virtual classroom environments and educational management system software independently and as adjuncts to live, interactive Internet-based audio/video transmission from classroom to classroom in multiple university-based programmes. This has been used for the following purposes [6]:

Communication between the university faculty, students and preceptors at clinical sites

Didactic lectures from expert clinicians to students assigned to distant clinical sites

Small group problem-based-learning modules designed to enhance students’ analytical skills

Conversion of traditional face-to-face lectures to asynchronous learning modules

Various Universities use e learning for their curriculum. One such called the ‘Edinburgh Electronic Medical Curriculum (EEMeC)’ has been there for medical undergraduate (MB ChB) degree programme since 1999 [7].

E Learning in Postgraduate Medical Education

E learning has been used both for continuing medical education (CME) and postgraduate university led qualifications.

Continuing Medical Education

One such CME programme using on line course for general practitioners in the management of type II diabetes is organised by the University of Boston. Interactive evidence-based modules with on line links were supplemented by on line discussion. Advantages noticed were better peer support, good discussion at forum and enhanced feedback [8].

There are several other on line resources to enhance continuing medical education in different branches of medicine including surgery e.g.

For surgical trainees helping with membership examinations of the Royal College of Surgeons—http://www.surgical-tutor.org.uk

For surgeons to learn laparoscopic surgery skills—http://www.websurg.com

UK National Health Service E learning for health resource for all health care workers—http://www.e-lfh.org.uk/projects/

University-Led E Learning Surgical Qualifications

A number of postgraduate university-led distance learning surgical qualifications have been going on for the last few years. Some of these include the following:

Edinburgh surgical qualification (ESSQ) University of Edinburgh, surgical qualification distance learning programme. (http://www.essq.rcsed.ac.uk/site/2741/essq_overview.aspx)

Medical education University of Dundee. http://medicine.dundee.ac.uk/course/postgraduate-certificate-medical-education

MCh Master’s level General Surgery University of Edinburgh. http://www.chm.rcsed.ac.uk

MS Coloproctology University of East Anglia. http://www.uea.ac.uk/study/postgraduate/taught-degree/detail/ms-coloproctology-part-time

MS oncoplastic breast University of East Anglia. http://www.uea.ac.uk/study/postgraduate/taught-degree/detail/ms-oncoplastic-breast-surgery-part-time

E Learning Versus Traditional Medical Education—Available Evidence

Medical education has traditionally been instructor-led. Comparing this with e learning would provide evidence to support the effectiveness and efficiency of e learning. Due to the multifaceted nature of e learning including content quality, technological characteristics and specific e learning intervention, multiple components need to be examined for this purpose [7]. The three areas most intensively studied are on product utility, cost-effectiveness and learner satisfaction.

Product utility meaning usefulness and efficiency of the course have shown e learning at least as effective and more efficient learning and better retention in both randomised and nonrandomised studies [9–11]. E learning provided more independent learning through materials that can be easily updated [11]. In a cluster randomised controlled trial by Kulier et al., a clinically integrated e learning evidence based medicine (EBM) curriculum in reproductive health compared with a self-directed EBM course resulted in higher knowledge and skill scores and improved educational environment [12].

A study at the University of Boston consisting of 105 students compared traditional clinical placement with online student clerkships for diabetes. Students completing the online clerkship demonstrated greater gains in reported evidence-based management skills from pre to post-clerkship, larger increases in mean score (from pre to post) on a medical-humanism aptitude scale and higher scores on a post-clerkship diabetes management assessment [13].

Another study compared third year medical students receiving traditional lecture (group A, n = 73) to group B (n = 75) who were asked to use website containing text and pictures augmented by podcast on a common proctology condition haemorrhoids. There was significantly greater knowledge gain in group B (web/podcast) than in group A (lecture) [14].

E learning has been shown to have cost savings due to reduced travel and labour costs, reduced institutional infrastructure and the possibility of expanding programmes with new educational technologies [10, 11].

The student satisfaction has been shown to be consistently high in e learning [9, 10]. It is important to note that e learning does not replace instructor-led training completely. Some form of facilitation by the supervisor such as on line tutorial is required. Multimedia such as text, graphics, animation, audio and video can be used to produce engaging content. In surgery, some direct supervision at their place of work by a consultant is still required and this is called blended-learning strategy [9].

MS Coloproctology as an Example of E Learning in Surgery

Need for Online MS Coloproctology

Traditionally, the four surgical Royal Colleges in London, Edinburgh, Glasgow and Ireland have played a central role in the delivery of training in the British Isles. The UK higher surgical training has been shaped to current format after several reforms including the 1993 Calman report and the more recent Sir John Tooke’s report [15, 16]. The Intercollegiate Surgical Curriculum Project (ISCP) established by the Royal Colleges has produced formal curriculum. The Specialty Advisory Committee (SAC) representing the four Royal Colleges, General Medical Council (GMC) and regional deaneries oversee surgical training.

At the end of the training, the trainee should be able to deliver services at the level of consultant specialist. There are several challenges in training a colorectal surgeon to the level of consultant despite several reforms. The introduction of European Working Time Directive (EWTD) in 2009 to 48 h a week has reduced the number of possible working hours to 15,000 h in a 7-year training period [17]. There is evidence that the total number of elective operations performed by trainees has reduced by as much as 80 % from the mid 1980s to mid 2000s [18]. The ISCP curriculum is detailed but the trainees find it difficult to achieve them in the current environment of reduced working time and obligation of service delivery in addition to training need.

The University of East Anglia (UEA) conducted a trainee survey via Dukes Club and Association of Surgeons in Training (ASIT) to all colorectal trainees in the UK to identify areas of training needs of current training programme. Seventy-five percent of the respondents surveyed reported gaps in the current training programme. Perceived gaps were lack of continuity of care, subspeciality training and operative exposure mainly laparoscopic and colonoscopic [19].

To complement the current surgical training systems and to prepare the surgical trainee for consultant colorectal surgeon, UEA developed MS Coloproctology course as 60 % of the UEA trainee survey respondents felt this would provide additional benefit to the current training [19]. This subspeciality MS degree would be an additional advantage to intercollegiate FRCS (Gen Surg) degree they would have otherwise generally acquired. Delivery of the course mostly at virtual on line environment (VLE) would provide flexible training being able to contribute this on their spare time and would not be affected by the EWTD requirements. The first MS Coloproctology course was launched in January 2013.

Course Structure

Learning outcomes have been identified for each topic and standard set at year one consultant coloproctologist level. These learning outcomes are aimed at higher levels of Bloom’s taxonomy of learning domains towards application, analysis, evaluation and creation of knowledge rather than just remembering and understanding facts [20]. All learning domains—cognitive (knowledge), psychomotor (skills) and affective (attitudes) are taken into consideration whilst writing up the learning outcomes.

The course curriculum has been developed in order to cover all aspects of modern coloproctology bearing in mind the product of the course as a year one consultant. There are four subject-related modules (colorectal emergencies, inflammatory bowel disease, neoplasia, and proctology and functional bowel). Two additional generic modules one on research and the other on management are included.

Research module encompasses research, audit and service evaluation empowering trainees to conduct and supervise research within the National Health Service (NHS) setting, writing and succeeding in submitting research protocols, evaluating research methodologies and literature reviews. The management and service delivery module develops clinical leadership, interpersonal skills, conflict resolution, developing new service and innovation, evaluation and delivery of the latest government policies. This module has been included to bridge the gap in the present standard specialty training programme.

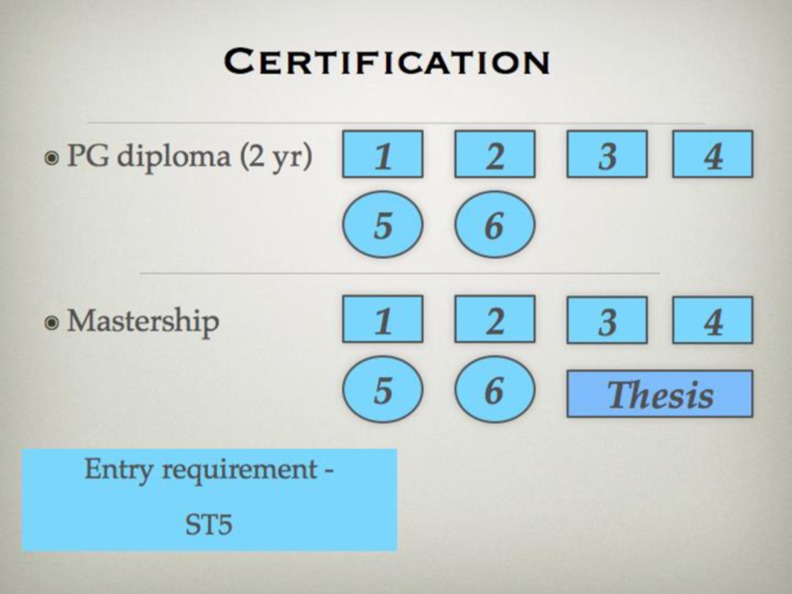

Successful completion of these six modules followed by thesis at the end completes the course with award of MS qualification (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Course structure

Each of the six modules include seven topics, each topic being covered over in a 2-week split. Hence, each module runs over 16 weeks, last 2 weeks to cover revision time required before the end of module examinations. The thesis should be completed within 12 months. The total time required for completion of full masters is 2.5 to 3 years (Fig. 2). Each week, the student needs approximately 10 h of study time not conflicting with their working time at the hospital.

Fig. 2.

Certification

Virtual Learning Environment

On line virtual learning environment (VLE), which can be accessed 24 h a day by students and e tutors at any time of their convenience, at most electronic devices making this flexible educational tool is the main hub for the delivery of the course (Fig. 3). This is password protected and all forms of modern media including text, audio, video, X rays and images can be used for enhanced delivery of the content. Table 1 shows the 2-week VLE programme.

Fig. 3.

Virtual learning environment (VLE)

Table 1.

Biweekly format for each topic

| Week 1 | Week 2 |

|---|---|

| • PBL scenario presented, reading list given • Forum discussion with e tutor mediation • Formative assessment using MCQ, EMQ • Learning outcomes given |

• Clinical reasoning scenario presented • Forum discussion with e tutor mediation • Tests of clinical reasoning (SCT) • Expert opinion on clinical reasoning scenario • Achieve all learning outcomes |

MCQ multiple choice questions, EMQ extended match questions, SCT script concordance testing

Week 1

Problem-based learning (PBL), the starting point for learning the topic not only provides opportunity to solve that problem but also stimulates learning related to that problem [21]. PBL and reading list is presented on day 1 of week 1. The students learn, discuss and debate the management of this problem supported by latest evidence among peers on line facilitated by faculty e tutors. Towards the later part of the week, they solve formative multiple choice questions (MCQs) and extended match questions (EMQs) in order to cheque their progress to achieve all learning outcomes on that topic. The on line discussion takes place asynchronously making it flexible for e tutors and trainees with their time.

Week 2

In week 2, students are presented with more complex case (clinical reasoning scenario) to encourage them to apply and evaluate their knowledge and skills gained from the first week. On line discussion here focusses on decision-making skills and clinical reasoning skills. During this week, script concordance testing (SCT) a new way of testing the decision-making skill is used for further formative assessment. It allows testing on real-life situations that are not adequately measured with current tests. It probes the multiple judgements that are made in the clinical reasoning process which may be for diagnosis, investigation or treatment. The scoring being a Likert scale reflects the degree of concordance of student’s judgements to those of a panel of expert faculty [22, 23].

Learning is a constructive process and new knowledge is acquired on existing knowledge. The e tutors act as facilitator and motivator to encourage further learning by creating a friendly environment. Each e tutor is expected to spend at least 2 h each week on e tutor and support.

Assessments

Assessment is a key element of the course giving opportunity to assess knowledge and professional skills. This takes place throughout each module through formative (EMQ, MCQ, SCT, on line discussion) and summative methods. The summative assessment is not on line and takes place every 16 weeks at RCS Eng or UEA Norwich consisting of 60 MCQs or EMQs in the morning. This is followed by training day for the next module encompassing interactive lectures and practical course. This provides opportunity to visit the faculty and face-to-face interaction. There is practical examination at the end of four coloproctology subject-related modules in at nine objective structured clinical examinations (OSCEs) stations. These include structured viva, clinical skills, complex case management, advanced communication skills and log book station including procedure based assessment (PBA).

Practical Operating Experience for Trainees

The clinical environment the students are working is of paramount importance and supervising consultant act as local educational supervisor for this course. They should have performed index operations to stage 4 on PBA meaning they can perform operations independently and can deal with complications. It is possible that the students may not have enough exposure in a particular branch of coloproctology during their clinical placements. In order to address this problem, a group of link surgeons has been set up among the national faculty. This provides opportunities for students to go and visit these centres and get more experience.

Student Feedback

Every 16 weeks towards the completion of each module, students are asked to give detailed feedback on course content, VLE and e tutors on line. The feedback is discussed after summative assessment in the presence of the students, faculty, learning technologist and university staff. Any areas needing improvement are acted upon. The module 1 feedback was very encouraging (Fig. 4). The VLE has been evaluated very user-friendly with course accessibility on mobile devices. Learning technologists are available at any time to assist with technical aspects of VLE.

Fig. 4.

Student feedback

Conclusion

The e learning has several advantages over traditional learning. University lead higher surgical qualifications can be delivered successfully to high student satisfaction. However, this cannot replace traditional training completely. Supervision in surgery is of paramount importance in surgical procedures during training. The increasing use of e learning with focussed training by supervisor face-to-face on occasions called blended learning is likely to enhance surgical training worldwide.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

The authors receive no monetary benefit from the University of East Anglia.

References

- 1.Mason R, Kaye A. Mindweave: communication, computers and distance education. Oxford: Pergamon Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bates A. Technology, e-learning and distance education. London: Routledge; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson HM (2007) Dialogue and the construction of knowledge in e-learning: exploring students’ perceptions of their learning while using Blackboard’s asynchronous discussion board. European Journal of Open, Distance and E-Learning 05.01.2007 (2007) [ISSN 10275-207

- 4.Recommendation 1836 (2008) Realising the full potential of e-learning for education and training. Council of Europe. Retrieved 14 Sep 2013

- 5.Broudo M, Walsh C. MEDICOL: online learning in medicine and dentistry. Acad Med. 2002;77(9):926–927. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200209000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Riley JB, Austin JW, Holt DW, et al. Internet-based virtual classroom and educational management software enhance students’ didactic and clinical experiences in perfusion education programs. J Extra Corpor Technol. 2004;36(3):235–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ellaway RH (2005) Evaluating a virtual learning environment in medical education. PhD Thesis, The University of Edinburgh

- 8.Wiecha J, Barrie N. Collaborative online learning: a new approach to distance CME. Acad Med. 2002;77(9):928–929. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200209000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chumley-Jones HS, Dobbie A, Alford CL. Web-based learning: sound educational method or hype? A review of the evaluation literature. Acad Med. 2002;77(10 suppl):S86–S93. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200210001-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruiz JG, Mintzer MJ, Leipzig RM. The impact of E-learning in medical education. Acad Med. 2006;81(3):207–212. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200603000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kulier R, Gülmezoglu AM, Zamora J, et al. Effectiveness of a clinically integrated e-learning course in evidence-based medicine for reproductive health training: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;308(21):2218–2225. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.33640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kulier R, Coppus SF, Zamora J, et al. The effectiveness of a clinically integrated e-learning course in evidence-based medicine: a cluster randomised controlled trial. BMC Med Educ. 2009;9:21. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-9-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wiecha JM, Vanderschmidt H, Schilling K. HEAL: an instructional design model applied to an online clerkship in family medicine. Acad Med. 2002;77(9):925–926. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200209000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhatti I, Jones K, Richardson L, Foreman D, Lund J, Tierney G. E-learning vs lecture: which is the best approach to surgical teaching? Color Dis. 2011;13(4):459–462. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.02173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calman K (1993) Hospital doctors: training for the future. The report of the working group on specialist medical training. Health Publications Unit

- 16.Tooke J. Final report of the independent inquiry into modernising medical careers: aspiring to excellence. London: Aldridge Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomas RL, Karanjia N. Comparison of SHO surgical logbooks a generation apart. Bull R Coll Surg Engl. 2009;91(suppl):356–359. doi: 10.1308/147363509X475781. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Temple J. Time for training. A review of the impact of the European Working Time directive on the quality of training. May 2010. (http://www.mee.nhs.uk/pdf/JCEWTD_Final%20report.pdf). Accessed 7 July 2013

- 19.Aryal K, Speakman C, Miles A, Pereira J (2013) National trainee survey on university led specialist coloproctology qualification an E learning course of the 21st century. Color Dis s3:56.P042

- 20.Anderson LW, Krathwohl DR, Airasian PW, et al. A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: a revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. New York: Pearson, Allyn & Bacon; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davis MH, Harden RM. AMEE medical education guide no 15: problem-based learning: a practical guide. Med Teach. 1998;21(2):130–140. doi: 10.1080/01421599979743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Charlin B, Vleuten C. Standardized assessment of reasoning in context of uncertainty. The Script Concordance Test approach. Eval Health Prof. 2004;27:304–319. doi: 10.1177/0163278704267043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meterissian SH. A novel method of assessing clinical reasoning in surgical residents. Surg Innov. 2006;13(2):115–119. doi: 10.1177/1553350606291042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]