Abstract

Objectives

To analyse the clinical features, inflammatory markers and radiographs of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) cases with lobe or multi foci infiltration; with a special focus on factors which allow the differential diagnosis of viral and mycoplasma pneumonia.

Setting

Retrospective chart review of CAP cases in a large university teaching hospital.

Participants

126 paediatric CAP cases, with lobe or multi foci infiltration, presenting between May 2012 and April 2013. Demographic data, clinical presentation on admission or referral, laboratory tests, prior history, and radiography were collected for each case if available.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

We used univariate and multivariate logistic regression to determine the significant factors which allow the differential diagnosis of viral and mycoplasma CAP with lobe or multi foci infiltration.

Results

There were 71 (56%) male and 55 (44%) female CAP cases with lobar or multi foci infiltration. 70 pneumonia cases were caused by Mycoplasma pneumoniae and 18 by viruses. Univariate analysis of the mycoplasma and viral causes of the CAP revealed that increased respiratory rate, wheeze, male gender and lymphocyte percentage were the factors associated with the differentiation of mycoplasma and viral aetiologies of pneumonia (p<0.05). A stepwise logistic regression analysis was performed to assess independent factors which allow the differential diagnosis of viral and mycoplasma pneumonia. Increased respiratory rate, wheeze, and lymphocyte percentage were reliable independent factors which allow the differential diagnosis of viral and mycoplasma CAP with lobar or multi foci infiltration.

Conclusions

Whether the CAP with lobar or multi foci infiltration was caused by mycoplasma species or viruses could not be inferred from the radiological patterns. Wheeze, lymphocyte percentage and respiratory rate were independent factors which allowed the differential diagnosis of viral and mycoplasma CAP with lobar or multi foci infiltration.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Over a period of 1 year, a retrospective study was carried out in our hospital. A stepwise logistic regression analysis of 88 cases was performed to assess independent predictors which allowed the differential diagnosis of viral and mycoplasma community-acquired pneumonia (CAP).

Increased respiratory rate, wheeze and lymphocyte percentage were significantly predictive regarding the differentiation between viral and mycoplasma CAP with lobar or multi foci infiltration, as was viral aetiology of CAP with lobar or multi foci infiltration, increased respiratory rate, wheeze and increased lymphocyte percentage.

This study has several limitations. First, it was a retrospective study, and therefore there may have been some selection bias. Second, viral pneumonia could be missed due to the sensitivity of immunofluorescence and the limited number of viruses we detected. Third, there may be some cases in which the patient had a viral as well as bacterial or a combined bacterial and mycoplasma infection which cannot be detected.

Introduction

For the paediatric population, community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is among the most frequent causes of hospital admission. CAP remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, especially regarding children less than 5 years of age. Most children with CAP live in the developing countries.1 Viruses and mycoplasma species are two main of the many pathogenic agents which can cause CAP.2–4

The symptoms of CAP vary considerably depending on its aetiology, infection pattern, and underlying medical conditions. In clinical practice, most CAP diagnoses are based on radiography and clinical symptoms. Some cases have been reported in which the aetiology of CAP was established on the basis of clinical signs, radiological findings or non-specific inflammatory serum markers.5–7 In radiography, most CAP cases are indicated by patchy areas of lung consolidation distributed along the lung markings, and diagnosed as bronchopneumonia. However, lobe or multi foci infiltration are the two other important types of CAP in clinical practice.

Both viruses and mycoplasma species can lead to lobe or multi foci infiltration in CAP. The therapeutic strategy for CAP cases is as controversial as it is crucial. The use of antibiotics before the aetiology is determined is debated. On the other hand, to establish the cause of CAP needs time. Hence, tests must be devised which allow an early differentiation between viral and mycoplasma pneumonia. Unfortunately, studies focusing on CAP with lobe or multi foci infiltration have not yet been carried out.

Therefore, from May 2012 to May 2013, over a period of 1 year, a retrospective study was carried out in our hospital to examine the clinical features, inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein (CRP), white blood cell count and lymphocyte percentage), and radiographs of CAP cases with lobe or multi foci infiltration, with a special focus on factors which would allow the differential diagnosis of viral and mycoplasma pneumonia.

Materials and methods

Study subjects

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Children's Hospital Affiliated to Soochow University. Informed written consent was obtained from the parents of all children. During a surveillance period of 12 months (from May 2012 to April 2013), 126 consecutive, previously healthy children with radiologically confirmed lobar or multi foci infiltration of the lung were treated at our hospital. The medical charts, radiographs and laboratory findings were retrospectively reviewed by both a respiratory physician and a radiologist. Patients with history of asthma were excluded.

Nasopharyngeal swab specimens were routinely collected within 24 h of admission, and bronchial-aspirate samples were obtained after tracheal intubation. Respiratory specimens were tested for influenza A and B, adenovirus, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), bokavirus, human metapneumovirus, and parainfluenza virus (PIFV) 1, 2 and 3, using direct immunofluorescence assays. Viral pneumonia was defined as acute respiratory disease with abnormal chest radiograph findings and positive laboratory tests for one of the aforementioned viruses. In addition, blood specimens were obtained within 24 h of admission for bacterial cultures. Other blood tests, including for CRP, white blood cells, and lymphocyte percentages and neutrophil percentages, were also performed.

The diagnosis of mycoplasma pneumonia was based on the results from real-time PCR targeting the P1 cytoadhesion type 1 and 2 genes of the Mycoplasma pneumoniae genome, using DNA extracted from nasopharyngeal swab specimens. Mycoplasma pneumonia was defined as acute respiratory disease with abnormal chest radiograph findings and positive laboratory tests combined with real-time PCR. Patients with simultaneous viral and mycoplasma infections were excluded.

Radiography

The symptoms typically occurred at 4–7 days before the chest radiographs, via an anteroposterior projection with the child lying down. Images was independently reviewed by two radiologists; in case of different opinions, a diagnostic conclusion was reached by consensus. Chest radiograph findings were classified as lobar or multi foci infiltration (unilateral or bilateral). The distribution of abnormalities was categorised as lobar, multi foci. A lobar distribution was defined as a single abnormal lobe. If there were two or more foci (unilateral or bilateral), the distribution of abnormality was considered multi foci.3 Pleural effusion was evaluated by both chest radiograph and ultrasound.

Factors analysis

One hundred and twenty-six CAP patients were analysed with respect to gender, fever, wheeze, increase of respiratory rate, cough, CRP and radiological findings among three different age groups: 0–23 months, 2–4 years, and older than 5 years. Then, incidence of proven viral and mycoplasma CAP was investigated. Of the 88 proven CAP patients, fever, increase of respiratory rate, CRP, white blood cells (WBC), cough, wheeze and radiological findings were statistically analysed.

The respiratory rates of the 126 patients were age-related; less than 45 per minute in children younger than 28 days old, less than 40 per minute in children between 29 days and 1 year old, less than 30 per minute in children between 1 and 3 years old, less than 25 per minute in children between 4 and 7 years old, and less than 20 per minute in children older than 8 years.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as number (n) and percentage. Univariate comparisons were made using non-parametric one-way Wilcoxon rank sum, χ2 or Fisher's exact tests, depending on the statistical distribution. To evaluate the ability to differentiate between mycoplasma and viral CAP cases with lobar or multi foci infiltration, a stepwise logistic regression analysis was performed with the SAS V8.0. Probability values of p<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Overall, there were 71 (56%) male and 55 (44%) female CAP cases with lobar or multi foci infiltration. The median age of the 126 patients was 4 years (range 11 days to 14 years). The presenting signs and symptoms were fever (47.6%), wheeze (14.3%) (without history of asthma), increase of respiratory rate (55.6%) and cough (97.6%). Fever and increase of respiratory rate are more common in the ‘older than 5 years’ group; however, wheeze is more common in ‘0–23 months’ group (see table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical signs and symptoms in 126 children with community-acquired pneumonia, in relation to age

| Symptoms | 0–23 months (n=34) |

2–4 years (n=39) |

≥5 years (n=53) |

p Value | Total (n=126) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fever >37.5°C | 7 | 22 | 31 | 0.0011 | 60 |

| Wheeze | 13 | 2 | 3 | <0.0001 | 18 |

| Increased respiratory rate | 12 | 17 | 41 | 0.0001 | 70 |

| Cough | 32 | 38 | 53 | 0.2131 | 123 |

| CRP (>8) | 10 | 27 | 39 | <0.0001 | 76 |

| Lobar infiltration | 11 | 18 | 25 | 0.9524 | 54 |

| Unilateral infiltration (multiple) | 5 | 8 | 13 | 0.9524 | 26 |

| Bilateral infiltration | 18 | 13 | 15 | 0.0587 | 46 |

| Pleural effusion | 1 | 2 | 4 | 0.8847 | 7 |

| Sex (M) | 24 | 16 | 31 | 0.0364 | 71 |

CRP, C-reactive protein.

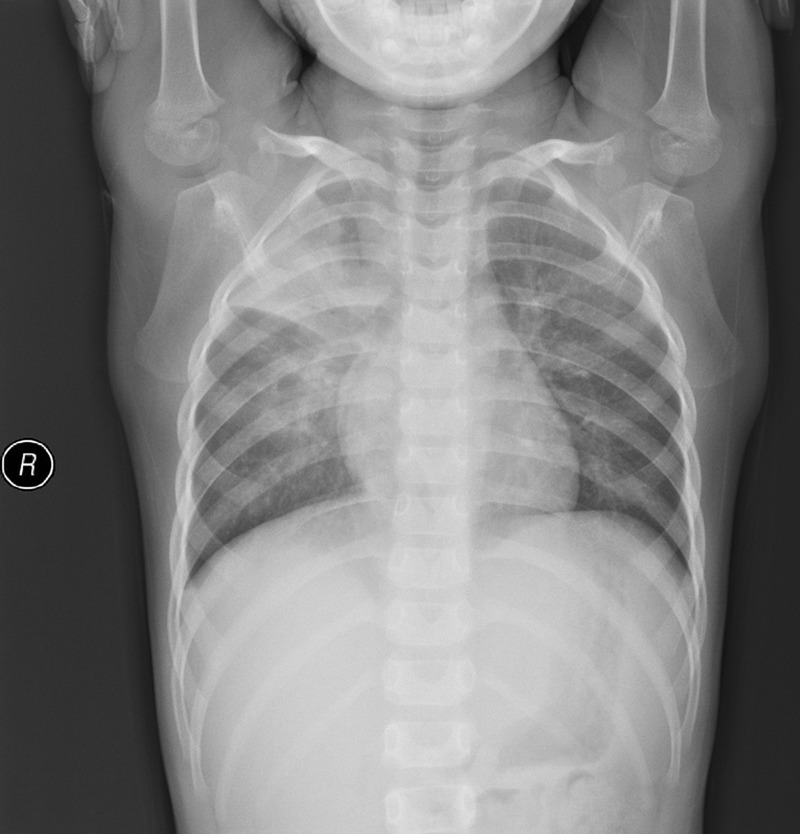

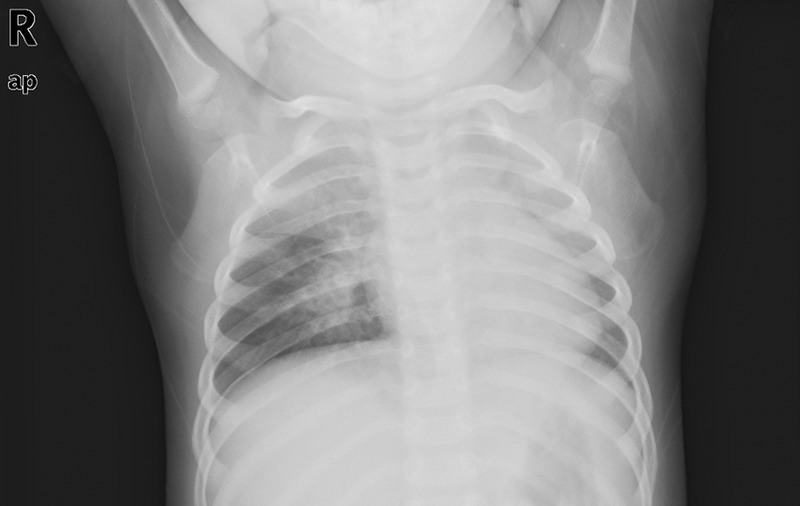

Findings in chest radiographs included lobar infiltration (see figure 1) in 54 patients, multi foci infiltration including unilateral infiltration (see figure 2) in 26 patients, and bilateral infiltration (see figure 3) in 46 patients. Seven patients had pleural effusions. An analysis of the correlation between aetiology and radiography findings showed that there were no significant differences between them (p>0.05) (table 2).

Figure 1.

An example of right middle lobe infiltration from a chest radiograph obtained 6 days after the onset of symptoms in a patient with influenza B.

Figure 2.

An example of right upper and middle lobe infiltration from a chest radiograph obtained 5 days after the onset of symptoms in a patient with mycoplasma pneumonia.

Figure 3.

An example of bilateral infiltration in the left upper zone, the right upper zone and middle zone from a chest radiograph taken 4 days after the onset of symptoms in a patient with influenza A.

Table 2.

Radiological findings of community-acquired pneumonia in children with lobe or multi foci infiltration

| Radiological findings | Aetiology of pneumonia |

p Value | Total patients | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (n=70) | V (n=18) | Unknown (n=38) | |||

| Lobar infiltration | 28 | 7 | 19 | 0.8864 | 54 |

| Unilateral infiltration (multiple) | 15 | 3 | 8 | 0.8864 | 26 |

| Bilateral infiltration | 27 | 8 | 11 | 0.5192 | 46 |

| Pleural effusion | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1.0000 | 7 |

M, mycoplasma; V, viral.

Seventy of the CAP cases were caused by mycoplasma species and 18 by viruses: influenza A (n=2), influenza B (n=1), adenovirus (n=2), RSV (n=9), bokavirus (n=2) and PIFV 3 (n=2). Univariate analysis revealed that the factors which allowed the differential diagnosis of viral and mycoplasma CAP were increased respiratory rate, wheeze, male gender and lymphocyte percentage (p<0.05). There were no significant differences in age, radiological findings, fever, cough, CRP and WBC (p>0.05) (see table 3).

Table 3.

Clinical signs in relation to the aetiology of pneumonia, viral aetiology vs mycoplasma

| Findings | M (n=70) | V (n=18) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fever >37.5°C | 42 | 7 | 0.1078 |

| Wheeze | 3 | 8 | <0.0001 |

| Increased respiratory rate | 29 | 14 | 0.0053 |

| Cough | 69 | 16 | 0.1050 |

| CRP (>8) | 44 | 9 | 0.2231 |

| WBC (increase) | 17 | 6 | 0.4359 |

| Increased lymphocyte percentage | 10 | 7 | 0.0184 |

| Increased polymorphonuclear leucocytes percentage | 19 | 4 | 0.6717 |

| Radiograph | |||

| Multi foci infiltration (unilateral) | 15 | 3 | 0.7690 |

| Multi foci infiltration (bilateral) | 27 | 8 | 0.6498 |

| Sex (M) | 29 | 13 | 0.0197 |

| Age (>5 years) | 32 | 6 | 0.3442 |

CRP, C-reactive protein; M, mycoplasma; V, viral; WBC, white blood cells.

A stepwise logistic regression analysis of 88 cases was performed to assess independent predictors which allowed the differential diagnosis of viral and mycoplasma caused CAP. Increased respiratory rate, wheeze and lymphocyte percentage were significantly predictive regarding the differentiation between viral and mycoplasma caused CAP with lobar or multi foci infiltration (see table 4), as was viral aetiology of CAP with lobar or multi foci infiltration, increased respiratory rate, wheeze and increased lymphocyte percentage. The logistic regression model was consistent with the Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test (p=0.8979).

Table 4.

Stepwise logistic regression model for significant predictors of viral aetiology of community-acquired pneumonia showing lobar or multi foci infiltration

| Variable | χ2 | OR | 95% Wald CI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wheeze | 23.0077 | 0.063 | 0.010 to 0.271 | <0.0001 |

| Increased respiratory rate | 6.7243 | 0.093 | 0.013 to 0.653 | 0.0095 |

| Increased lymphocyte percentage | 8.9954 | 0.053 | 0.012 to 0.337 | 0.0027 |

Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test (p=0.8979).

Discussion

General findings in three age groups

In this study, about 69.8% of the CAP cases were caused by mycoplasma species or viruses. The aetiology of 38 cases (31.2%) could not be detected, partly because the positive of bacterial pathogens in blood culture is very low. Our results are very similar to those of Zhang et al,2 who reported 707 severe CAP cases; blood cultures were positive in only 5 (0.7%). This means that new methods with higher sensitivities for bacterial pathogens in blood must be devised which can be routinely used in all laboratories.8 On the other hand, 55.6% of our patients had tachypnoea and 47.6% had fever, and these symptoms were more common in the ‘older than 5 years’ group. CRP is higher in the ‘older than 5 years’ group than in the other two groups; maybe more infiltration foci can be found in the ‘older than 5 years’ group. Our results are similar to those of two other studies.9 10 However, wheeze is more common in the ‘0–23 months’ group; this finding is different from that of a recent study,11 partly because we focus on pneumonia with lobar or multi foci infiltration.

Radiological patterns between mycoplasma and viral CAP

In clinical practice, the radiographic detection of infiltrations is currently the gold standard for the diagnosis of CAP. Most CAP cases are diagnosed as bronchopneumonia by radiography. However, lobe or multi foci infiltrations are the other two radiological manifestations of CAP.3 11 Some authors have reported that in clinical practice lobar infiltrations are often caused by bacteria.6 However, in this study, 69.8% of the CAP cases were caused by viruses and mycoplasma species: mycoplasma was especially associated with aetiological findings, accounting for 55.6% in this group. This finding is consistent with some previous studies.3 12 In our study, there were 41 CAP cases with bilateral infiltrations and 61 CAP cases with multi foci. When analysed by distribution and the number of foci, there was no significant difference associated with aetiological findings. Even in some cases with pleural effusion, there was no significant difference associated with aetiological findings. This means that whether the CAP with lobar or multi foci infiltration was caused by mycoplasma species or viruses could not be inferred from the radiological patterns. In a recent study on paediatric CAP, Korppi et al11 analysed the clinical or radiological characteristics of 101 CAP cases; they concluded that radiographs are not helpful when it comes to differentiating between viral, pneumococcal and atypical bacterial aetiology of CAP in children. This conclusion coincides with our results the radiological pattern did not allow a reliable differentiation between mycoplasma and viral CAP.

Related factors between mycoplasma and viral CAP

To investigate potential factors that may allow differentiation between viral and mycoplasma CAP is very important for clinical practice. In this study, our aim was to describe the utility of some laboratory markers and clinical features regarding the differentiation between mycoplasma and viral CAP with lobar or multi foci infiltrations. Univariate analysis showed that findings such wheeze, lymphocyte percentage, respiratory rate and sex can help to differentiate between mycoplasma and viral CAP with lobar or multi foci infiltration. Furthermore, multiple logistic regression showed that wheeze, increase of lymphocyte percentage and increase of respiratory rate are independent factors which allow differentiation between mycoplasma and viral CAP with lobar or multi foci infiltration. Therefore, among mycoplasma and viral CAP with lobar or multi foci infiltration, wheeze, increase of lymphocyte percentage and increase of respiratory rate can help to diagnose viral pneumonia.

Hatipoğlu et al13 reported 147 viral CAP cases, and found that the prominent symptoms of the patients were cough (88.9%) and wheeze (72.2%). This is similar to our results. In another report,11 101 CAP cases were analysed. Although the report lacked data on respiratory rate in 20 cases, it included supplementary sensitivity analyses by adding the cases with missing data as non-tachypnoea cases in the analyses. Moreover, the report concluded that tachypnoea is not associated with the aetiology of CAP. The above study is different from our findings. The reason may be that we used multiple factor analysis and selected mycoplasma and viral CAP with lobar or multi foci infiltration as our object of study.

Youn et al9 reported 95 M pneumoniae cases with segmental or lobar infiltrations. They found that the lymphocyte percentage was at a normal level. Defilippi et al10 reported 102 CAP cases with a positive PCR for M pneumoniae: they found that the lymphocyte percentage (median) is at a normal level, a result similar to ours. Hatipoğlu et al13 reported 147 cases with pneumonia; the percentage of polymorphonuclear leucocytes in the viral pneumonia cases was lower than in patients in which virus was not isolated, suggesting that the lymphocyte percentage may be higher in the acute phase of pneumonia. The above-mentioned literature suggests that viral pneumonia often presents with a higher percentage of lymphocytes. This conclusion is similar to our results.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, it was a retrospective study, and therefore there may have been some selection bias. Second, viral pneumonia could be missed due to the sensitivity of immunofluorescence and the limit number of viruses we detected. Third, there may be some cases in which the patient had a viral as well as bacterial or a combined bacterial and mycoplasma infection which cannot be detected. Therefore, further, preferably prospective studies on CAP with lobar or multi foci infiltration are needed.

Conclusions

More than half of the CAP cases with lobar or multi foci infiltration are caused by mycoplasma species or viruses. Whether the CAP with lobar or multi foci infiltration is caused by mycoplasma species or viruses can not be inferred from the radiological patterns. We found that wheeze, lymphocyte percentage and respiratory rates are independent factors which allow the differential diagnosis of viral and mycoplasma caused CAP with lobar or multi foci infiltration, as is viral aetiology of CAP with lobar or multi foci infiltration, increased respiratory rate, wheeze and increased lymphocyte percentage.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: CH participated in study design and paper writing. WG and JW participated in data collection and paper writing. LZ participated in data collection and analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Institutional Review Board of the Children's Hospital Affiliated to Soochow University.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Rudan I, Boschi-Pinto C, Biloglav Z et al. Epidemiology and etiology of childhood pneumonia. Bull World Health Organ 2008;86:408–16. 10.2471/BLT.07.048769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang Q, Guo Z, Bai Z et al. A 4 year prospective study to determine risk factors for severe community acquired pneumonia in children in southern China. Pediatr Pulmonol 2013;48:390–7. 10.1002/ppul.22608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guo W, Wang J, Sheng M et al. Radiological findings in 210 paediatric patients with viral pneumonia: a retrospective case study. Br J Radiol 2012;85:1385–9. 10.1259/bjr/20276974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cardinale F, Cappiello AR, Mastrototaro MF et al. Community-acquired pneumonia in children. Early Hum Dev 2013;89(Suppl 3):S49–52. 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2013.07.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Don M, Valent F, Korppi M et al. Differentiation of bacterial and viral community-acquired pneumonia in children. Pediatr Int 2009;51:91–6. 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2008.02678.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Virkki R, Juven T, Rikalainen H et al. Differentiation of bacterial and viral pneumonia in children. Thorax 2002;57:438–41. 10.1136/thorax.57.5.438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Korppi M. Non-specific host response markers in the differentiation between pneumococcal and viral pneumonia: what is the most accurate combination? Pediatr Int 2004;46:545–50. 10.1111/j.1442-200x.2004.01947.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Esposito S, Marchese A, Tozzi AE et al. Bacteremic pneumococcal community-acquired pneumonia in children less than 5 years of age in Italy. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2012;31:705–10. 10.1097/INF.0b013e31825384ae [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Youn YS, Lee KY, Hwang JY et al. Difference of clinical features in childhood Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia. BMC Pediatr 2010;10:48 10.1186/1471-2431-10-48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Defilippi A, Silvestri M, Tacchella A et al. Epidemiology and clinical features of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in children. Respir Med 2008;102:1762–8. 10.1016/j.rmed.2008.06.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Korppi M, Don M, Valent F et al. The value of clinical features in differentiating between viral, pneumococcal and atypical bacterial pneumonia in children. Acta Paediatr 2008;97:943–7. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2008.00789.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee I, Kim TS, Yoon HK. Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia: CT features in 16 patients. Eur Radiol 2006;16:719–25. 10.1007/s00330-005-0026-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hatipoğlu N, Somer A, Badur S et al. Viral etiology in hospitalized children with acute lower respiratory tract infection. Turk J Pediatr 2011;53:508–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.