Abstract

Objective

To estimate the efficacy of a probiotic yogurt compared to a pasteurised yogurt for the prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea in children.

Design and setting

This was a multisite, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial conducted between September 2009 and 2012. The study was conducted through general practices and pharmacies in Launceston, Tasmania, Australia.

Participants and interventions

Children (aged 1–12 years) prescribed antibiotics, were randomised to receive 200 g/day of either yogurt (probiotic) containing Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG), Bifidobacterium lactis (Bb-12) and Lactobacillus acidophilus (La-5) or a pasteurised yogurt (placebo) for the same duration as their antibiotic treatment.

Outcomes

Stool frequency and consistency were recorded for the duration of treatment plus 1 week. Primary outcome was stool frequency and consistency, classified at different levels of diarrhoea severity. Due to the small number of cases of diarrhoea, comparisons between groups were made using Fisher's exact analysis.

Results

72 children commenced and 70 children (36 placebo and 34 probiotic) completed the trial. There were no incidents of severe diarrhoea (stool consistency ≥6, ≥3 stools/day for ≥2 consecutive days) in the probiotic group and six in the placebo group (Fisher's exact p=0.025). There was also only one episode of minor diarrhoea (stool consistency ≥5, ≥2 stools/day for ≥2 days in the probiotic group compared to 21 in the placebo group (Fisher's exact p<0.001). The probiotic group reported fewer adverse events (1 had abdominal pain, 1 vomited and 1 had headache) than the placebo group (6 had abdominal pain, 4 had loss of appetite and 1 had nausea).

Conclusions

A yogurt combination of LGG, La-5 and Bb-12 is an effective method for reducing the incidence of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea in children.

Trial registration number

Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry ACTRN12609000281291

Keywords: NUTRITION & DIETETICS

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Diarrhoea due to antibiotic therapy is a common complication. Numerous studies have suggested that specific probiotic supplements can prevent antibiotic-associated diarrhoea but none have examined the use of commercially available probiotic yogurt in children.

Often studies have examined diarrhoea as an all or none phenomenon, and not a spectrum of disease. We used the Bristol stool scale as an objective measure of stool frequency and consistency and classified these symptoms at different levels of diarrhoea severity.

This study shows that giving children on antibiotics a commercially available yogurt with probiotics Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG), Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacterium lactis reduced the incidence of gastrointestinal disturbance, including diarrhoea. Probiotic yogurt may have additional benefits of providing energy and nutrients that are lacking with probiotic supplements/capsules.

Introduction

Gastrointestinal (GI) upset is a well-known complication of broad-spectrum antibiotics, especially the β-lactams, clindamycin and vancomycin. These antibiotics may affect the function of normal bowel flora, cause overgrowth of unfavourable species such as Staphylococcus, Candida, Enterobacteriaceae, Klebsiella and Clostridium or cause changes in intestinal mucosa and motility.1 These changes often present as antibiotic-associated diarrhoea (AAD), which is distressing to both patients and carers and may result in poor compliance with antibiotic therapy.2 The frequency of AAD depends on the definition of diarrhoea and the age of the patient but is estimated to be between 11% and 30% for children on oral antibiotics.3 4

Probiotics are often recommended on the assumption that ingestion of ‘healthy’ bacteria will reduce the disturbance of gut microbiota and subsequent diarrhoea.5 Like pharmaceuticals, different probiotics exert different actions and have different effects. A number of clinical trials have used probiotics for the prevention of AAD. These studies have used a range of probiotics and have shown variable results. Meta-analyses show equivocal results due to the lack of homogeneity between studies.6 7 Sub-group analyses of the meta-analyses showed a significant reduction in AAD with the use of probiotics, namely Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG) and Saccharomyces boulardii.7–10 A number of methods have been used to administer these probiotics, including capsules, tablets and yogurts.2 4 11 12 The organisms used vary from a single species13 14 to multi-species cocktails,2 15 and the doses vary between studies, from 107 to 1010 colony-forming units (CFU).7

Studies on adults in hospital settings have shown LGG can be used to treat vancomycin resistant Enterococcus16 and prevent AAD and Clostridium difficile associated diarrhoea.17 In the paediatric setting, studies have tested probiotic tablets and powders for the prevention of AAD. Currently there is only one study examining probiotic yogurt that included children, but no studies have been done solely on children to examine the efficacy of an LGG containing probiotic yogurt.18 19 Probiotic yogurt/drinks are increasingly seen as attractive vehicles for delivery of probiotics because they are easily available, economical, easy to swallow, generally well tolerated and provide added energy, vitamins, minerals and protein when children are unwell. In Australia, the only commercially available yogurt containing LGG comes as a combination with Bifidobacterium lactis (Bb-12) and Lactobacillus acidophilus (La-5).

Previous studies6 7 assessing the effect of probiotics for patients on antibiotics have focused only on the presence or absence of AAD. The WHO defines diarrhoea as three loose stools a day for two or more days.20 This approach fails to address the spectrum of type and severity of GI symptoms, which can range from minor to serious. Even minor symptoms may have an impact on children, their parents and compliance with treatment. Additionally, researchers have used different definitions of diarrhoea with differences in what frequency (two or three times a day for two consecutive days) constitutes diarrhoea, and the term ‘loose’ has not always been quantified.2 4 14 15 21 Although each study will be internally consistent, the different definitions do not allow for the comparison of absolute rates between different studies. Consequently, we have presented our results with a range of diarrhoea definitions, permitting a better understanding of both disease severity and comparison with previous work.

This study investigates the efficacy of yogurt containing LGG (strain deposit number (SDN) ATCC53103), Bb-12 (SDN DSM15954) and La-5 (SDN DSM13241), compared to a placebo, in reducing the rate of AAD in children on antibiotics.

Patients and methods

This was a multisite stratified (prior history of AAD/no prior history of AAD), randomised, double-blind, parallel, placebo-controlled clinical trial. The study took place in two general practices and four pharmacies in Launceston, a regional town in Tasmania, Australia, with a catchment area of 100 000 people. General practitioners/pharmacists approached parents who presented with outpatient children aged 1–12 years prescribed broad-spectrum oral antibiotics. Children were excluded if they had a history of milk allergy or intolerance, antibiotic treatment within the previous 2 months, prophylactic antibiotic treatment, use of a probiotic product for medicinal purposes within the previous 7 days, immunodeficiency, chronic GI disease and acute or chronic diarrhoea. Parents were fully informed about the aims of the study, and written informed consent was obtained from at least one parent. The Human Research Ethics Committee (Tasmania) Network, Australia approved the study protocol (H0010498).

Using data from Koning's study,22 a sample size of 58 compared using a t test (1.5 stools/day, SD 0.5/day) would detect a minimum relative reduction in frequency of 25% (power 80%; α 0.05). The reduction of 25% was chosen after informal discussion with clinicians as to what effect size they would consider significant enough to recommend the use of probiotic yogurt to patients they commenced on antibiotics. A sample size of 70 completed was chosen with 20% over-sampling as it was planned to use ordered logistical regression. The statistical methods were revised before the data analysis was commenced. To better understand the extent of the GI distress, we chose to use different definitions of diarrhoea as the outcome measure and this mandated time to event analyses (Cox proportional hazards regression).

A statistician generated independent allocation sequences and randomisation lists for each study site, using the random number generator in Microsoft Excel. As prior AAD has been shown to be a predictor of subsequent AAD, participants were stratified on their history of AAD.19 To avoid a disproportionate number of patients between treatment groups, randomisation at each site was performed in blocks of 10 (5 placebo and 5 probiotic). To ensure allocation concealment, an independent person oversaw the packaging and labelling of trial treatments based on the randomisation schedule. All investigators, participants, outcome assessors and data analysts were blinded to the assigned treatment throughout the study.

Children received yogurt (2×100 g tubs/day) from the start to the end of their antibiotic treatment. The probiotic yogurt (Vaalia, a commonly available brand in supermarkets) contained LGG (mean dose 5.2×109 CFU/day), Bb-12 (mean dose 5.9×109 CFU/day) and La-5 (mean dose 8.3×109 CFU/day). In contrast, the placebo yogurt was a pasteurised yogurt containing S thermophilus (mean dose 4.4×104 CFU/day) and L bulgaricus (mean dose 1.2×103 CFU/day). Both the probiotic and the placebo yogurt were supplied by Parmalat (Brisbane, Queensland, Australia) who had no role in the formulation or conduct of the study or in the data analysis or interpretation. An independent laboratory assessed the CFU content. The yogurt was in 100 g containers with identical labels. The yogurts were similar in taste but one yogurt was thinner in texture. Participants were only shown the yogurt they were going to use and did not have the opportunity to make a comparison. Instructions were provided on giving the yogurt and maintaining a diary for the duration of treatment plus 1 week. This time was chosen as the average onset of diarrhoea after commencement of antibiotics in children is 5.3±3.5 days (range 0–15 days).3

On enrolment, baseline data for age, sex, weight, antibiotic and dose, usual bowel frequency and history of prior AAD was collected. Information on prior history of AAD was used for stratification during randomisation. Parents were given a diagrammatic representation of the Bristol Stool Scale (BSS) for children23 and shown how to rate their children's stool for consistency. They were also provided with a diary to record information on stool frequency and consistency, antibiotic and yogurt consumption (both trial and any other yogurt) and adverse symptoms.

The primary outcome was the efficacy of probiotic yogurt in prevention of diarrhoea, classified at different levels of severity: for example, less severe (stool frequency ≥2/day for 2 or more days with stool consistency ≥5 on the BSS); more severe (stool frequency ≥3/day for 2 or more days with stool consistency ≥6 on the BSS).

The raw data of stool frequency and consistency was processed into a series of categories representing thresholds for different levels of disease severity (which were analysed based on event frequency), and then also analysed based on the time of first occurrence (event dated from the start of symptoms) of: stool frequency of two or more a day; stool frequency of three or more a day; stool consistency of type 5 (soft blobs with clear-cut edges, passed easily); and stool consistency of type 6 (fluffy pieces with ragged edges, a mushy stool). Similarly, the time to first occurrence of diarrhoea was calculated for each individual in the study using various definition of diarrhoea. These included: (A) stool consistency ≥5 and stool frequency ≥2/day for more than 2 days; (B) stool consistency ≥5 and stool frequency ≥3/day for more than 2 days; (C) stool consistency ≥6 and stool frequency ≥2/day for more than 2 days; and (D) stool consistency ≥6 and stool frequency ≥3/day for more than 2 days.

Time to first occurrence (event dated from the start of symptoms) data was compared between the placebo and the probiotics groups by estimating HRs using Cox proportional hazards regression adjusting for age, sex, susceptibility to antibiotic induced diarrhoea and the class of antibiotics. Fisher's exact test was used to compare the number of events of diarrhoea between the two groups. To check for compliance for antibiotic and yogurt intake, mean daily intake was calculated for each participant and then compared between the two groups. Where multiple outcomes were assessed, a corrected α was calculated to assist interpretation of the estimated effects using the Holm–Bonferroni method: this method assumes that the outcomes are independent, but takes into account the results of all the outcome assessments together. All analyses were performed using Stata SE/V.13.0.

Results

Seventy-two participants were recruited between September 2009 and August 2012, but two did not return their details or trial results. Seventy children completed the study (29 girls, 41 boys; age 6.6±3.0 years; weight 28.2±11.0 kg; 36 placebo group, 34 probiotic group). Baseline characteristics (table 1) were generally similar, but there were relatively more girls in the placebo group than in the probiotic group, and more children in the placebo group received antibiotic treatment below the recommended dose based on the Australian Medicines Handbook guidelines.24

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Characteristics | Placebo (n=36) | Probiotic (n=34) |

|---|---|---|

| Previous AAD/no previous AAD | 9/27 | 5/29 |

| Mean age (year (SD)) | 6.3 (3.2) | 6.8 (2.7) |

| Male/female | 24/12 | 17/17 |

| Weight (kg (SD)) | 28.0 (12.8) | 28.4 (9.1) |

| β-lactams | 34 (94%) | 30 (89%) |

| Macrolides | 1 (3%) | 4 (12%) |

| Tetracyclines | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) |

| Below recommended dose of antibiotics | 19 (53%) | 12 (38%) |

| Recommended dose of antibiotics | 16 (44%) | 17 (53%) |

| Above recommended dose of antibiotics | 1 (3%) | 3 (9%) |

| Unknown dose of antibiotics | 0 (0%) | 2 (6%) |

| Completed antibiotic treatment | 27 (75%) | 29 (85%) |

| Stool frequency daily or 2nd daily | 33 (92%) | 31 (91%) |

| Stool frequency other than daily or 2nd daily | 3 (8%) | 3 (9%) |

| Reason for antibiotic use | ||

| Ear infection | 20 (56%) | 18 (53%) |

| Throat infection | 8 (22%) | 9 (26%) |

| Chest infection | 3 (8%) | 3 (9%) |

| Other/unknown | 5 (14%) | 4 (12%) |

Values are number (percentage) unless otherwise stated.AAD, antibiotic-associated diarrhoea.

Seven children in the placebo group and five from the probiotic group took <90% of prescribed antibiotics. Fewer children in the placebo group consumed ≥80% of the prescribed yogurt (20 vs 25) compared to the probiotic group. Statistically there was no significant difference (all p>0.09) in the children who were compliant in taking medication and/or yogurt between the two groups.

There were more adverse events reported in the placebo group (6 had abdominal pain, 4 had loss of appetite and 1 had nausea) compared to the probiotic group (1 had abdominal pain, 1 vomited and 1 had headache). The mean±SD duration of antibiotic treatment was 5.6±2.2 days.

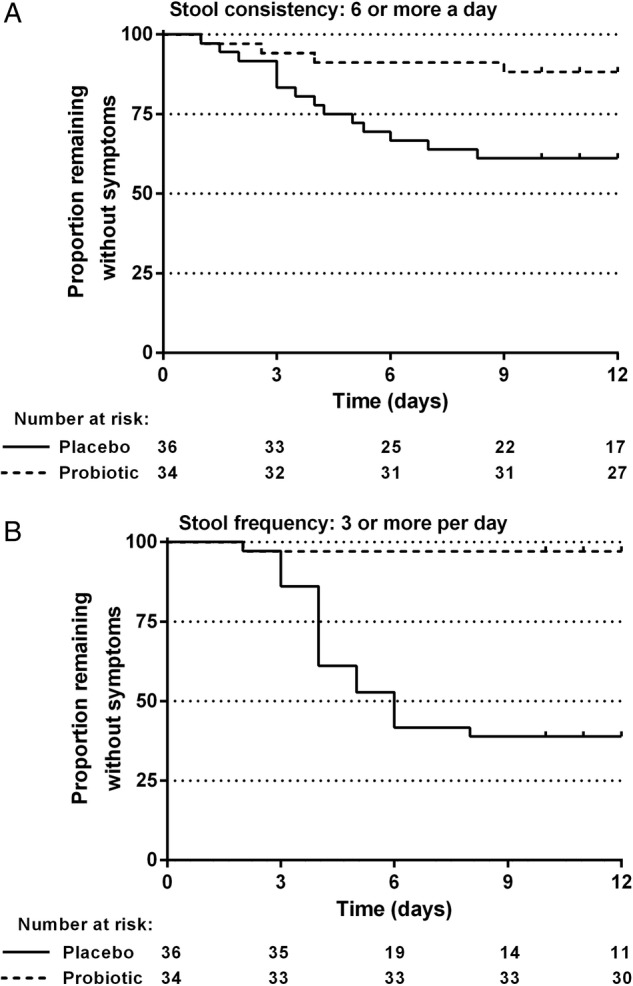

Table 2 compares the number of cases of diarrhoea by different definitions. Figure 1 shows a comparison of time of onset of the first occurrence of a stool frequency ≥3/day or stool consistency ≥6. Cox proportional hazard regression analysis showed that in comparison to the placebo group, the probiotic group had fewer events of stool frequency ≥2 (HR 0.14, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.62, p=0.01), stool frequency ≥3 (HR 0.04, 95% CI 0.004 to 0.29, p=0.002), stool consistency ≥5 (HR 0.18, 95% CI 0.08 to 0.38, p<0.001) and stool consistency ≥6 (HR 0.11, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.41, p=0.001). Analyses were also conducted to assess the differences in results for children with and without known susceptibility of diarrhoea in response to antibiotic treatment, and these differences were not significant (all p>0.7).

Table 2.

Comparison of cases of diarrhoea by different definitions in placebo and probiotic groups

| Definitions of diarrhoea | Placebo cases/total participants | Probiotic cases/total participants | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| A (SC ≥5, ≥2 stools/day for ≥2 days) | 21/36 | 1/34 | <0.001 |

| B (SC ≥5, ≥3 stools/day for ≥2 days) | 16/36 | 0/34 | <0.001 |

| C (SC ≥6, ≥2 stools/day for ≥2 days) | 8/36 | 0/34 | 0.005 |

| D (SC ≥6, ≥3 stools/day for ≥2 days) | 6/36 | 0/34 | 0.025 |

| Any of the above | 27/36 | 1/34 | <0.001 |

Fisher's exact analysis. Stool consistency (SC) data is based on the Bristol Stool Scale.

Holm–Bonferroni corrected α values: A=0.01; B=0.0125; C=0.025; D=0.05; Any=0.0167.

Figure 1.

Proportion of children at risk for the first occurrence of (A) stool consistency score of ≥6; and (B) stool frequency of ≥3 stools a day. Stool consistency of 6 corresponds to fluffy pieces with ragged edges of loose mushy stool based on the Bristol Stool Scale. The solid line represents the placebo group and the dashed line represents the probiotic group.

Discussion

This study was conducted in children aged 1–12 in an outpatient setting. In all classifications of diarrhoea there were significantly fewer incidences in children given a probiotic rich yogurt in comparison to children on a placebo yogurt. No children in the probiotic group experienced severe diarrhoea compared to six in the placebo group. There was only one child with mild diarrhoea (definition A) in the probiotic group and 21 in the placebo group. There was a significant reduction in duration and a delay in onset of increased stool frequency and stool consistency for children given a probiotic yogurt. This shows that an easily available yogurt provides a relevant reduction in AAD in children at the same time as providing energy and nutrition.

While children have not previously been tested with a LGG probiotic yogurt, the results of this study are consistent with previous trials in adults on antibiotics given LGG yogurt21 and children given LGG supplements.11 13 15 25 Prior studies using different probiotics have shown variable effects and meta-analyses show equivocal results due to lack of homogeneity between studies.6 7 This suggests that not all probiotics are the same, so each probiotic needs to be tested for its efficacy in a specific context.26 A recent review recommends further studies of probiotics in an outpatient setting.27 This research begins to fill this gap. In general, previous studies have reported on the incidence of diarrhoea as an all-or-none phenomenon and as such may not reflect the real world impact of GI distress. Our study demonstrates that there is a wide spectrum of apparent response to probiotics, depending on which levels of disease severity are analysed: mild events are associated with relatively low estimates of benefits from probiotics, whilst more severe events are associated with much larger estimates of benefits. Thus the apparent heterogeneity may be due in part to measurement issues.

Increased stool frequency or loose bowel movements can be distressing for the child or parents/carers. They may not be particularly concerned whether they have met the WHO definition of diarrhoea.20 Symptoms of increased frequency or liquid consistency may cause premature termination of antibiotic therapy, missed days from school or day care and, by association, lost days of work for parents/carers.28 Definitions of diarrhoea in earlier studies have varied; some using two or more loose stools/day,2 13 some using three or more loose stools/day,4 11 12 15 19 21 25 29 and another using more than three times normal frequency.14 In general, studies have failed to specify their criteria for loose stools2 4 11 15 19 21 25 29 or created their own definition.13 To reduce subjective variability, this study used the BSS, a reliable and validated method to assess stool consistency.23 Stools are rated from 1 (separate hard lumps) to 7 (watery with no solid lumps). Using this approach we were able to create a range of definitions of diarrhoea and analyse the effect across a spectrum of disease as well as allow comparison with previous trials. Across all measures, there was an apparently large statistically significant reduction in symptoms for the children receiving the probiotic-rich yogurt, with no suggestion of a smaller effect in those with more severe symptoms. At the same time, yogurt is easy to administer and provides a palatable source of calories, vitamins, minerals and protein when children may not be inclined to eat or drink because of their illness.

A limitation of this trial is that the effects on stool were only recorded for the duration of antibiotic treatment plus 1 week; there may have been further incidents outside this time frame that have not been reported. This time frame was chosen as studies have noted that the majority of incidents of AAD occur within the first 2 weeks of commencing antibiotics,3 11 and we were concerned with the issue of compliance with data collection for a longer follow-up period. This study relied on self-report by either the parents or child. When the child was at school or day care, reporting and recording in the diary may have been less than complete. As noted by Lane, children under the age of 8 are less reliable in their use of the modified BSS,23 however, in the post-trial questionnaire, all the participants found the stool chart easy to use and often a conversational piece. The placebo yogurt was not tested for ability to induce or reduce diarrhoea. It would seem unlikely that the placebo should have caused diarrhoea, as the incidence of diarrhoea in the placebo group was consistent with previous studies.3 4 A further limitation may be the time it took to recruit the patients, almost 3 years, which may have caused a selection bias. It also highlights the difficulty of recruitment in busy outpatient clinics.

All p values are lower than the α values corrected for multiple hypothesis testing (Holm–Bonferroni). The consistent trend of the results across all definitions of diarrhoea makes a type-1 error unlikely.

The mechanism by which probiotics reduce diarrhoea may be via modulation of the host immune system or on the composition of the GI microbiota and their by-products.30 This study was not designed to investigate these mechanisms and additional microbiological study is warranted. Currently clinical studies randomly test probiotics for their therapeutic potential. In the future these studies could be better targeted if their mechanism of action was understood.

Conclusion

This study, conducted in a community setting for an everyday problem that affects hundreds of thousands of children each year, using an economical, easily accessible, nutritious food, shows that a yogurt combination of LGG, La-5 and Bb-12 is an effective method for reducing the incidence of antibiotic-associated GI disturbance in children.

Footnotes

Contributors: MF was responsible for literature search, study design, data management, data interpretation and writing. KDKA was responsible for data analysis, data interpretation and writing. IKR was involved in study design, statistical analysis plan and data interpretation. MJB and RE were involved in data interpretation and writing of the manuscript.

Funding: The study was supported by Parmalat Australia.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee (Tasmania) Network, Australia. All authors had full access to the data and take full responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Hogenauer C, Hammer HF, Krejs GJ et al. Mechanisms and management of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea. Clin Infect Dis 1998;27:702–10. 10.1086/514958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beniwal RS, Arena VC, Thomas L et al. A randomized trial of yogurt for prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea. Dig Dis Sci 2003;48:2077–82. 10.1023/A:1026155328638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turck D, Bernet JP, Marx J et al. Incidence and risk factors of oral antibiotic-associated diarrhoea in an outpatient pediatric population. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2003;37:22–6. 10.1097/00005176-200307000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kotowska M, Albrecht P, Szajewska H. Saccharomyces boulardii in the prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea in children: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2005;21:583–90. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02356.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hawrelak JA. Probiotics, prebiotics and symbiotics. J Complim Med 2007;6:28–35. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hawrelak JA, Whitten DL, Myers SP. Is Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG effective in preventing the onset of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea: a systematic review. Digestion 2005;72:51–6. 10.1159/000087637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnston BC, Goldenberg JZ, Vandvik PO et al. Probiotics for the prevention of pediatric antibiotic-associated diarrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011:(11);CD004827 10.1002/14651858.CD004827.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McFarland LV. Meta-analysis of probiotics for the prevention of antibiotic associated diarrhoea and the treatment of Clostridium difficile disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2006;101:812–22. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00465.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lemberg DA, Ooi CY, Day AS. Probiotics in paediatric gastrointestinal diseases. J Paediatr Child Health 2007;43:331–6. 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2007.01076.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McFarland LV, Goh S. Preventing pediatric antibiotic associated diarrhoea and Clostridium difficile infections with probiotics: a meta-analysis. World J Meta-Anal 2013;1:102–20. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arvola T, Laiho K, Torkkeli S et al. Prophylactic Lactobacillus GG reduces antibiotic-associated diarrhoea in children with respiratory infections: a randomized study. Pediatrics 1999;104:e64 10.1542/peds.104.5.e64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Correa NB, Peret Filho LA, Penna FJ et al. A randomized formula controlled trial of Bifidobacterium lactis and Streptococcus thermophilus for prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea in infants. J Clin Gastroenterol 2005;39:385–9. 10.1097/01.mcg.0000159217.47419.5b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vanderhoof JA, Whitney DB, Antonson DL et al. Lactobacillus GG in the prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea in children. J Pediatr 1999;135:564–8. 10.1016/S0022-3476(99)70053-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seki H, Shiohara M, Matsumura T et al. Prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea in children by clostridium butyricium MIYAIRI. Pediatr Int 2003;45:86–90. 10.1046/j.1442-200X.2003.01671.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Szymanski H, Armanska M, Kowalska-Duplaga K et al. Bifidobacterium longum PL03, Lactobacillus rhamnosus KL53A, and Lactobacillus plantarum PL02 in the prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea in children: a randomized controlled pilot trial. Digestion 2008;78:13–17. 10.1159/000151300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manley KJ, Fraenkel MB, Mayall BC et al. Probiotic treatment of vancomycin-resistant enterococci: a randomised controlled trial. Med J Aust 2007;186:454–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hickson M, D'Souza AL, Muthu N et al. Use of probiotic Lactobacillus preparation to prevent diarrhoea associated with antibiotics: randomised double blind placebo controlled trial. BMJ 2007;335:80 10.1136/bmj.39231.599815.55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fox MJ, Ahuja KDK, Eri RD. Efficacy of probiotics in the prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea (AAD) in children—a review. Int J Probiotics Prebiotics 2013;8:61–6. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Conway S, Hart A, Clark A et al. Does eating yogurt prevent antibiotic-associated diarrhoea? A placebo-controlled randomised controlled trial in general practice. Br J Gen Pract 2007;57:953–9. 10.3399/096016407782604811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization. Health Topics—Diarrhoea, 2013. http://www.who.int/topics/diarrhoea/en/

- 21.Wenus C, Goll R, Loken EB et al. Prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea by a fermented probiotic milk drink. Eur J Clin Nutr 2008;62:299–301. 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koning CJ, Jonkers DM, Stobberingh EE et al. The effect of a multispecies probiotic on the intestinal microbiota and bowel movements in healthy volunteers taking the antibiotic amoxycillin. Am J Gastroenterol 2008;103:178–89. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01547.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lane MM, Czyzewski DI, Chumpitazi BP et al. Reliability and validity of a modified Bristol stool form scale for children. J Pediatr 2011;159:437– 41.e1 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Australian Medicines Handbook 2012, Australian Medicines Handbook Pty Ltd; Adelaide.

- 25.Ruszczynski M, Radzikowski A, Szajewska H. Clinical trial: effectiveness of Lactobacillus rhamnosus (strains E/N, Oxy and Pen) in the prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea in children. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2008;28:154–61. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03714.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pham M, Lemberg DA, Day AS. Probiotics: sorting the evidence from the myths. Med J Aust 2008;188:304–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Butler CC, Duncan D, Hood K. Does taking probiotics routinely with antibiotics prevent antibiotic associated diarrhoea? BMJ 2012;344:e682 10.1136/bmj.e682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Surawicz CM. Antibiotic-associated diarrhoea in children: how many dirty diapers? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2003;37:2–3. 10.1097/00005176-200307000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beausoleil M, Fortier N, Guenette S et al. Effect of a fermented milk combining Lactobacillus acidophilus Cl1285 and Lactobacillus casei in the prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Can J Gastroenterol 2007;21:732–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oelschlaeger TA. Mechanisms of probiotic actions—A review. Int J Med Microbiol 2010;300:57–62. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2009.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]