Abstract

CD4+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) are critical for maintaining self-tolerance and function to prevent autoimmune disease. High densities of intratumoral Tregs are generally associated with poor patient prognosis, a correlation attributed to their broad immune-suppressive features. Two major populations of Tregs have been defined, thymically derived natural Tregs (nTregs) and peripherally induced Tregs (iTregs). However, the relative contribution of nTregs versus iTregs to the intratumoral Treg compartment remains controversial. Demarcating the proportion of nTregs versus iTregs has important implications in the design of therapeutic strategies to overcome their antagonistic effects on antitumor immune responses. We used epigenetic, phenotypic, and functional parameters to evaluate the composition of nTregs versus iTregs isolated from mouse tumor models and primary human tumors. Our findings failed to find evidence for extensive intratumoral iTreg induction. Rather, we identified a population of Foxp3-stable nTregs in tumors from mice and humans.

Introduction

Two major subsets of regulatory T cells (Tregs) have been defined based on their developmental origin. Thymus-derived natural Tregs (nTregs) are characterized by constitutive Foxp3 expression, whereas Foxp3 is considered unstable in peripherally induced (adaptive) Tregs (iTregs) (1). The difference in Foxp3 stability supports the view that iTregs retain the plasticity to revert to conventional CD4+ T cells (Tconvs) (2, 3). Inducible Tregs are routinely generated in vitro from Tconvs via TCR stimulation in the context of IL-2 and TGF-β (3). By various parameters, in vitro–generated iTregs are comparable to nTregs; however, withdrawal of TGF-β from iTreg cultures results in rapid loss of Foxp3 expression, correlating with a reversion to cells akin to Tconvs (3). Conversely, Foxp3 expression by nTregs is TGF-β independent, evidenced by the normal nTreg frequency and function in TGF-β–deficient mice (4). This difference in the ability to revert to Tconv provides an operational paradigm to distinguish the two populations; however, defining nTregs and iTregs ex vivo from lymphoid or tumor tissues remains a challenge. Approaches such as genomewide epigenetic analysis of Treg and Tconv populations have uncovered unique differences in their chromatin regulation (1). In-depth analysis of the Foxp3 locus revealed differential CpG DNA methylation patterns (differentially methylated regions [DMRs]) between Treg subsets, improving Treg lineage delineation (2). Despite these advances, epigenetic characterization of both mouse and human intratumoral Treg subpopulations remains unclear.

TGF-β has been extensively implicated in the neoplastic process, with deregulation of the growth factor correlated with a poor prognosis (5). The association between tumor progression and TGF-β signaling is highlighted by research supporting that neutralizing TGF-β in tumors may have a positive therapeutic benefit (6). Adding to this thesis is the notion that inhibiting TGF-β signaling may also reduce intratumoral iTregs, providing an attractive therapeutic strategy to counter Treg-mediated immune suppression. However, the composition and source of tumor-infiltrating Tregs remains contentious, with several conflicting lines of evidence to support either the accumulation of nTregs, intratumoral Tconv-to-iTreg conversion, or a combination of both sources (7–11). Using orthogonal methodologies, we were unable to find evidence to support de novo intratumoral Tconv-to-Treg conversion. Instead, we observed a population of Foxp3-stable nTregs in multiple syngeneic and carcinogen-induced mouse tumor models. Importantly, these findings extended to an evaluation of human non–small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) and ovarian carcinoma. Together, our data clarify a paradigm for understanding Treg stability in tumors and argue against the impact of strategies aiming to achieve iTreg-to-Tconv reversion as a means of cancer therapy.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines

4T1, Lewis Lung (LLC), CT26, MC-38, and Detroit562 tumor cell lines were maintained in supplemented RPMI 1640 or DMEM at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator.

Mice and in vivo studies

C57BL/6, BALB/c, FVB, and Nu-Foxn1 mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories. BALB/c- and C57BL/6J-Foxp3EGFP mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. For tumor growth studies, tumor cells were suspended in 100 μl PBS and injected orthotopically (4T1, 5 × 104 cells) or s.c. (Detroit562, 6 × 106 cells; LLC, CT26, and MC-38, 5 × 105 cells). Spontaneous fibrosarcomas were initiated in FVB mice by s.c. injection of methylcholanthrene (MCA, 100 μg) in 0.1 ml corn oil. TGF-β–Trap (TGF-βRII extracellular domain fused to human IgG1) was injected i.v. at the indicated dose. Latent and free-active serum TGF-β levels were determined by ELISA.

Flow cytometry

Mouse Abs were CD3, CD4, CD25, Foxp3, GITR, Eos, CTLA-4, Ki67, and CD16/32. Human Abs were CD3, CD4, CD25, CD127, FOXP3, and FcγR-block. Dead cells were excluded using 7-aminoactinomycin D. Intracellular staining was conducted using eBioscience Foxp3 Fix/Perm buffer kit.

Cell isolation

Mouse tumor cells were isolated as described previously (12). Human tumor specimens were collected before therapy and purchased from Conversant Bio. Healthy donor PBMCs (Research Blood Components) were isolated using Ficoll-Paque density gradient. Samples were filtered and enriched for CD4+ T cells by MACS depletion (Miltenyi Biotec). After FcγR blockade, samples were incubated with CD3, CD4, and CD25 (and CD127 for human samples) Abs for 45 min at 4°C. When Foxp3EGFP mice were not used, Foxp3 was detected by intracellular staining. Stained cells were sorted using a BD FACSAriaIII.

CpG methylation

CpG methylation analysis was determined by pyrosequencing of bisulphite-modified genomic DNA from purified Tconvs and Tregs (>95% enriched). Methylation analysis was conducted by EpigenDx, as previously described (13). CpG residues for each loci are shown as single boxes. Assays were Foxp3 (ADS568FS1/2), CTLA-4 (ADS378FS1/2), TNFSFR18 (ADS4018RS1/2), Ikzf4 (ADS3785FS1/2), and human FOXP3 (ADS783FS1/2).

iTreg generation and ex vivo Treg stability

Tconvs and Tregs from the tumor or spleen of tumor-bearing Foxp3EGFP mice were cultured in the presence of 100 ng/ml recombinant mouse IL-2 (Peprotech), CD3/CD28 Dynabeads (2:1 bead/cell ratio; Life Technologies), with or without 10 ng/ml recombinant human TGF-β (rhTGF-β; R&D Systems) for 3 d. On day 3, cells were washed and replated in 100 ng/ml IL-2 in the presence or absence of 10 ng/ml rhTGF-β. On day 5, viable CD3+ CD4+ cells were analyzed for Foxp3EGFP expression. Irradiated (20 Gy), Thy1.2-depleted splenocytes (MACS depletion >90%, Miltenyi Biotec) from tumor-free mice were used to support tumor-derived Tconvs and Tregs (1:1 ratio).

Smad luciferase assay

4T1 cells, transduced with a pSmad luciferase reporter (SA Biosciences), were plated overnight (5 × 104cells/100μl RPMI 1640). Cells were incubated with TGF-β–Trap for 2 h before rhTGF-β was added (20 ng/ml). The next day, fresh media were added with 150 μg/ml d-Luciferin and samples were analyzed after 5 min.

Results and Discussion

Preliminary assessment of Tconvs (CD3+ CD4+ CD25low Foxp3−) and Tregs (CD3+ CD4+ CD25high Foxp3+) from tumor-bearing BALB/c- and C57BL/6J-Foxp3EGFP mice (CT26 and MC-38, respectively) revealed a skewed Treg/Tconv ratio in the tumor compared with spleen or blood (Supplemental Fig. 1A). Consistent with proliferation contributing to this altered ratio, Ki67 expression was elevated in intratumoral Tregs relative to Tconvs (Supplemental Fig. 1B). Phenotypic characterization of intratumoral Tregs revealed a marked upregulation of Treg signature genes (CTLA-4, GITR, and Eos), a characteristic likely attributed to Tregs responding to tissue-specific and/or tumor neoantigens (Supplemental Fig. 1C) (7, 14).

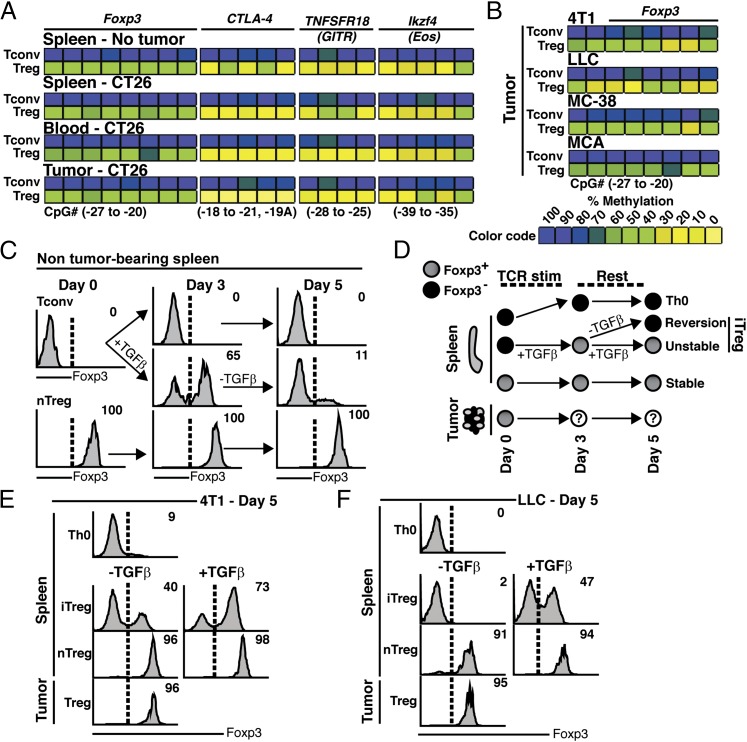

CpG hypomethylation of the Foxp3 Treg-specific demethylated region (TSDR) or conserved noncoding sequence 2 is a hallmark of nTregs (2). Hypomethylation of cis-elements at the Foxp3 locus permits Foxp3 binding, as well as other transcription factors that constitutively activate Foxp3 (13, 15). By contrast, Tconvs and iTregs share a highly methylated Foxp3 locus (Supplemental Fig. 2A) (2). As a result, Foxp3 expression in iTregs is unstable but can be induced by TGF-β signaling (13). We sought to use methylation analysis to define the intratumoral Treg landscape. Remarkably, we observed that intratumoral Tregs exhibited a uniform pattern of Foxp3 TSDR hypomethylation at multiple time points (Fig. 1A and Supplemental Fig. 1D). This epigenetic profile extended to the DMRs of CTLA-4 (CD152), GITR (CD357, TNFRSF18), and Eos (Ikzf4) (Fig. 1A and Supplemental Fig. 1D). In contrast, Tconvs from either tumor-bearing or control mice had a hypermethylated signature. Importantly, the intratumoral Treg Foxp3 TSDR pattern was conserved in additional mouse tumor models: 4T1, LLC, MC-38, and MCA-induced fibrosarcoma (Fig. 1B).

FIGURE 1.

Intratumoral Tregs from several mouse tumor models exhibit Foxp3 stability. (A) CpG methylation analysis of Foxp3, CTLA-4, TNFRSF18, and Ikzf4 from Tconvs and Tregs isolated from the indicated tissue of CT26 tumor-bearing and control mice (pooled, n = 5 mice). (B) Foxp3 TSDR methylation analysis of Tconvs and Tregs from LLC, 4T1, MC-38, MCA-induced tumors (pooled, n = 5 mice). Color coding represents percentage methylation. (C) Tconvs (Foxp3EGFP−) or nTregs (Foxp3EGFP+) were cultured under iTreg (+TGF-β) or Th0 conditions (−TGF-β) for 3 d. Th0, iTregs, and nTregs were incubated in fresh culture media for an additional 2 d (day 5), then analyzed for Foxp3 expression (profiles from n = 5 spleens). The percentage of cells expressing Foxp3 is relative to freshly isolated Tconvs (upper right of histogram). (D) Ex vivo differentiation schematic for cells cultured with TGF-β (iTreg) or without TGF-β (iTreg-to-Tconv, “Reversion”). (E and F) Representative histograms showing the percent of T cells expressing Foxp3 after 5 days of ex vivo culture. Tconvs and Tregs were isolated from spleens and tumors of 4T1 (E) or LLC (F) tumor-bearing mice and subjected to culture conditions outlined in (D). Samples were pooled from n = 5 mice for each model. Tumors were collected when volumes reached 500 mm3. All data are representative of two or more individual experiments.

In the context of TCR stimulation, TGF-β effectively converts Tconvs into iTregs and can be monitored by the acquisition of Foxp3 expression and suppressive activity (3). When TGF-β is withdrawn from iTreg cultures, Foxp3 expression rapidly diminishes (Fig. 1C). By contrast, splenic nTregs maintain Foxp3 expression in the absence of TGF-β stimulation. In agreement with earlier reports, iTregs that upregulated Foxp3 in response to TGF-β retained a hypermethylated epigenetic profile relative to the hypomethylated DMRs of cultured nTregs (Supplemental Fig. 2A) (15). To further interrogate the composition of intratumoral Tregs, we used the following schema (Fig. 1D). As expected, withdrawal of TGF-β from iTregs led to reduced Foxp3, as compared with iTreg continually supplemented with TGF-β (Fig. 1E). As a control, splenic nTregs were shown to retain Foxp3 expression independent of TGF-β. Consistent with their hypomethylated Foxp3 TSDR, Foxp3 was uniformly stable in intratumoral Tregs (Fig. 1A, 1E). This finding was reproduced in another tumor model (LLC), confirming that intratumoral Tregs have stable Foxp3 expression (Fig. 1F).

To discount the possibility that intratumoral Treg Foxp3 stability was due to paracrine or autocrine TGF-β production, we sought to neutralize TGF-β in vivo using a TGF-βRII–Fc fusion protein (TGF-β–Trap). The efficiency of TGF-β neutralization by TGF-β–Trap was first evaluated in vitro, using a 4T1-Smad-Luc cell line, and in vivo by treating mice implanted with Detroit562 pharyngeal carcinoma cells, whose growth is driven by autocrine TGF-β signaling (16). As anticipated, administration of TGF-β–Trap effectively ablated endogenously and exogenously induced TGF-β signaling in 4T1 cells in vitro and delayed tumor growth in mice (Supplemental Fig. 2B–D).

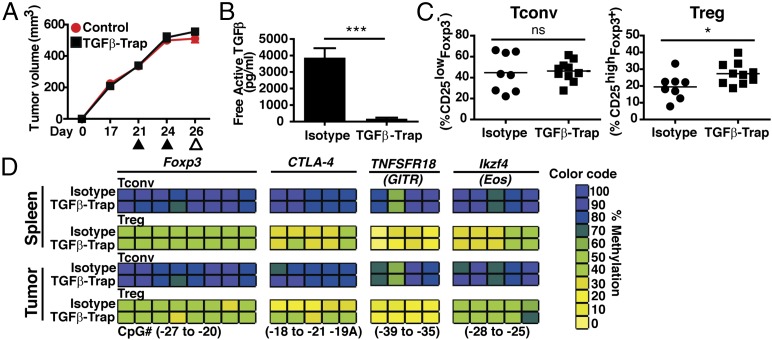

Pre-established 4T1 tumor-bearing mice received TGF-β–Trap to evaluate the impact of TGF-β neutralization on intratumoral Treg stability (Fig. 2A). Despite neutralization of TGF-β in the serum of tumor-bearing mice, TGF-β–Trap failed to reduce the frequency of intratumoral Tregs relative to an isotype-treated cohort (Fig. 2B, 2C). TGF-β neutralization upon tumor cell implantation provided a modest decrease in tumor growth (Supplemental Fig. 2E). However, even if TGF-β–Trap treatment was initiated at the time of tumor implantation, there was no reduction of intratumoral Treg frequency, arguing against a role for TGF-β in recruiting or enhancing intratumoral Treg proliferation (Supplemental Fig. 2F). Further, methylation analysis revealed that TGF-β–Trap treatment failed to alter the epigenetic signature of tumor-infiltrating Tregs (Fig. 2D).

FIGURE 2.

TGF-β neutralization does not impact intratumoral Treg accumulation. (A) 4T1 tumor-bearing mice (350–500 mm3) were treated i.v. with 492 μg TGF-β–Trap (n = 10) or isotype control (n = 8) on days 21 and 24 postimplantation (▴). Tissue was harvested on day 26 (△) for serum, phenotype, and methylation analysis. (B) Free active TGF-β in the serum of TGF-β–Trap or isotype-treated 4T1 tumor-bearing mice (n = 5 mice/group). (C) Percentage of Tconvs and Tregs, relative to the total CD4+ T cell population in TGF-β–Trap or isotype-treated mice. Each symbol represents an individual animal (n = 8–10/group). (D) CpG methylation analysis of Foxp3, CTLA-4, TNFRSF18, and Ikzf4 from Tconvs and Tregs isolated from the indicated tissues. Color coding represents percentage methylation. All data are representative of two or more independent experiments. Data are mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001 calculated using Student t test. ns, nonsignificant.

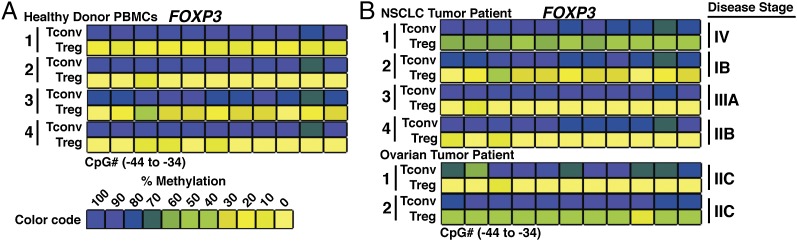

Having established the stability of Foxp3 in Tregs isolated from a number of mouse tumor models, we sought to apply these findings to Tregs from primary human tumor samples. Purified peripheral Tconvs and nTregs from healthy donors accurately reproduced the differentially methylated state of the Foxp3 TSDR observed in murine T cell populations (Fig. 3A and Supplemental Fig. 2A). To evaluate the methylation profile of Tregs in human tumors, we purified tumor-infiltrating Tregs from NSCLC and ovarian patient samples. Intratumoral Tregs showed a uniform degree of demethylation at the FOXP3 TSDR, as compared with the hypermethylated profile for tumor-infiltrating Tconvs (Fig. 3B). Taken together, we revealed striking concordance in the features of intratumoral Tregs isolated from mouse tumor models and primary human tumor samples.

FIGURE 3.

Human intratumoral Tregs have a hypomethylated FOXP3 TSDR profile. (A) CpG methylation analysis of the FOXP3 TSDR in Tconvs (CD3+ CD4+ CD127+ CD25low FOXP3−) and Tregs (CD3+ CD4+ CD25high CD127− FOXP3+) from the peripheral blood of healthy donors (n = 4). (B) FOXP3 TSDR methylation of intratumoral Tconvs and Tregs from NSCLC (n = 4) and ovarian cancer patients (n = 2). Color coding represents percentage methylation.

In this article, we provide several lines of evidence to support that nTreg-like cells populate tumors in mice and humans. This conclusion is consistent with the stability of Foxp3 expression in intratumoral Tregs from a range of murine tumor models, as well as FOXP3 TSDR hypomethylation in tumor-associated Tregs from mice and humans (1, 2, 15). Our data support a paradigm whereby lineage-stable nTregs are recruited into developing tumors, where they expand and contribute to localized immune suppression (7, 11), and moreover that Tconv-to-iTreg conversion is not an active process in tumors; rather, most Tregs recruited into the tumor are epigenetically imprinted nTreg-like cells. Our findings do not preclude that tumors arising in distinct anatomical locations under infectious or other inflammatory conditions may yield a more heterogeneous profile of iTregs and nTregs (17). Notably, therapeutic strategies to neutralize TGF-β in the tumor microenvironment would not impact the frequency of intratumoral Tregs. Rather, our results support the utility of therapeutic strategies that selectively deplete intratumoral Tregs or temporarily impair their immune-suppressive functions, without causing overt autoimmunity (12, 18, 19).

Supplementary Material

The online version of this article contains supplemental material.

- DMR

- differentially methylated region

- iTreg

- induced Treg

- MCA

- methylcholanthrene

- NSCLC

- non–small cell lung carcinoma

- nTreg

- natural Treg

- rhTGF-β

- recombinant human TGF-β

- Tconv

- conventional CD4+ T cell

- Treg

- regulatory T cell

- TSDR

- Treg-specific demethylated region.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ohkura N., Hamaguchi M., Morikawa H., Sugimura K., Tanaka A., Ito Y., Osaki M., Tanaka Y., Yamashita R., Nakano N., et al. 2012. T cell receptor stimulation-induced epigenetic changes and Foxp3 expression are independent and complementary events required for Treg cell development. Immunity 37: 785–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miyao T., Floess S., Setoguchi R., Luche H., Fehling H. J., Waldmann H., Huehn J., Hori S. 2012. Plasticity of Foxp3(+) T cells reflects promiscuous Foxp3 expression in conventional T cells but not reprogramming of regulatory T cells. Immunity 36: 262–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Selvaraj R. K., Geiger T. L. 2007. A kinetic and dynamic analysis of Foxp3 induced in T cells by TGF-beta. J. Immunol. 178: 7667–7677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fahlén L., Read S., Gorelik L., Hurst S. D., Coffman R. L., Flavell R. A., Powrie F. 2005. T cells that cannot respond to TGF-beta escape control by CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T cells. J. Exp. Med. 201: 737–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hasegawa Y., Takanashi S., Kanehira Y., Tsushima T., Imai T., Okumura K. 2001. Transforming growth factor-beta1 level correlates with angiogenesis, tumor progression, and prognosis in patients with nonsmall cell lung carcinoma. Cancer 91: 964–971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gorelik L., Flavell R. A. 2001. Immune-mediated eradication of tumors through the blockade of transforming growth factor-beta signaling in T cells. Nat. Med. 7: 1118–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malchow S., Leventhal D. S., Nishi S., Fischer B. I., Shen L., Paner G. P., Amit A. S., Kang C., Geddes J. E., Allison J. P., et al. 2013. Aire-dependent thymic development of tumor-associated regulatory T cells. Science 339: 1219–1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moo-Young T. A., Larson J. W., Belt B. A., Tan M. C., Hawkins W. G., Eberlein T. J., Goedegebuure P. S., Linehan D. C. 2009. Tumor-derived TGF-beta mediates conversion of CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells in a murine model of pancreas cancer. J. Immunother. 32: 12–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghiringhelli F., Puig P. E., Roux S., Parcellier A., Schmitt E., Solary E., Kroemer G., Martin F., Chauffert B., Zitvogel L. 2005. Tumor cells convert immature myeloid dendritic cells into TGF-beta-secreting cells inducing CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cell proliferation. J. Exp. Med. 202: 919–929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou G., Levitsky H. I. 2007. Natural regulatory T cells and de novo-induced regulatory T cells contribute independently to tumor-specific tolerance. J. Immunol. 178: 2155–2162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Curiel T. J., Coukos G., Zou L., Alvarez X., Cheng P., Mottram P., Evdemon-Hogan M., Conejo-Garcia J. R., Zhang L., Burow M., et al. 2004. Specific recruitment of regulatory T cells in ovarian carcinoma fosters immune privilege and predicts reduced survival. Nat. Med. 10: 942–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bulliard Y., Jolicoeur R., Windman M., Rue S. M., Ettenberg S., Knee D. A., Wilson N. S., Dranoff G., Brogdon J. L. 2013. Activating Fc γ receptors contribute to the antitumor activities of immunoregulatory receptor-targeting antibodies. J. Exp. Med. 210: 1685–1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zheng Y., Josefowicz S., Chaudhry A., Peng X. P., Forbush K., Rudensky A. Y. 2010. Role of conserved non-coding DNA elements in the Foxp3 gene in regulatory T-cell fate. Nature 463: 808–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goding S. R., Wilson K. A., Xie Y., Harris K. M., Baxi A., Akpinarli A., Fulton A., Tamada K., Strome S. E., Antony P. A. 2013. Restoring immune function of tumor-specific CD4+ T cells during recurrence of melanoma. J. Immunol. 190: 4899–4909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morikawa H., Ohkura N., Vandenbon A., Itoh M., Nagao-Sato S., Kawaji H., Lassmann T., Carninci P., Hayashizaki Y., Forrest A. R., et al. FANTOM Consortium 2014. Differential roles of epigenetic changes and Foxp3 expression in regulatory T cell-specific transcriptional regulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111: 5289–5294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Aarsen L. A., Leone D. R., Ho S., Dolinski B. M., McCoon P. E., LePage D. J., Kelly R., Heaney G., Rayhorn P., Reid C., et al. 2008. Antibody-mediated blockade of integrin alpha v beta 6 inhibits tumor progression in vivo by a transforming growth factor-beta-regulated mechanism. Cancer Res. 68: 561–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haribhai D., Lin W., Edwards B., Ziegelbauer J., Salzman N. H., Carlson M. R., Li S. H., Simpson P. M., Chatila T. A., Williams C. B. 2009. A central role for induced regulatory T cells in tolerance induction in experimental colitis. J. Immunol. 182: 3461–3468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bulliard Y., Jolicoeur R., Zhang J., Dranoff G., Wilson N. S., Brogdon J. L. 2014. OX40 engagement depletes intratumoral Tregs via activating FcγRs, leading to antitumor efficacy. Immunol. Cell Biol. 92: 475–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simpson T. R., Li F., Montalvo-Ortiz W., Sepulveda M. A., Bergerhoff K., Arce F., Roddie C., Henry J. Y., Yagita H., Wolchok J. D., et al. 2013. Fc-dependent depletion of tumor-infiltrating regulatory T cells co-defines the efficacy of anti-CTLA-4 therapy against melanoma. J. Exp. Med. 210: 1695–1710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.