Abstract

Background

Some three million Russian-speaking immigrants from the former Soviet Union live in Germany today. Many of them underwent a different kind of medical socialization than the indigenous population, but the experiences and expectations of this group of patients have hardly been studied to date.

Methods

In a qualitative study, 24 chronically ill native Germans and 25 chronically ill Russian-speaking immigrants were recruited via notices, through their primary care physicians, and by word of mouth and underwent a semi-structured interview in their mother tongue (German or Russian) about their experiences with their primary care physicians. The interviews were recorded using an audio device, translated into German if necessary, and transcribed, and their content was analyzed with the MAXQDA software package.

Results

The immigrants were less satisfied with their primary care physicians than the native Germans. This manifested itself in a weaker patient–physician connection and frequent changes of physician due to dissatisfaction with treatment. Both groups considered themselves inadequately informed about matters of health, but they gave differing reasons for this. On the other hand, the participants in both groups had practically the same general expectations from their primary care physicians. However, detailed analysis revealed cultural differences.

Conclusion

Physicians in Germany should be more aware of the culturally based expectations of immigrant patients in order to understand their needs better, improve the physician–patient relationship, and ensure equal opportunities in health care. For example, many immigrants would prefer their doctors to communicate with them in a manner that non-immigrants would consider paternalistic.

In the context of medical care migrants are often seen as difficult; this is the result of a lack of linguistic understanding, poorer compliance, and different disease concepts (1, 2). Primary care physicians report feeling uncertain, helpless, and even angry when working with migrants (2, 3). However, migration-specific health-care research almost always focuses on the point of view of medical professionals (4); little is known about immigrants’ own experiences. Whether they can report experiences similar to those of native-born citizens is an issue of interest.

The participants in the study presented here were first-generation Russian-speaking immigrants from the former Soviet Union. This group is the second-largest immigrant population in Germany and consists mainly of ethnic Germans, including late émigrés (“Russian-Germans”) and their relatives, Jewish immigrants, and migrants with other residency rights. For simplicity, Russian-speaking participants are referred to hereafter as “migrants,” and native-born citizens with no background of migration as “Germans,” even though most of the Russian-speaking participants are of German origin.

No research has yet been conducted into the expectations or experiences of Russian-speaking immigrants in a medical context. There is therefore no existing information on whether migrants are as integrated into medical care, in terms of equality of opportunity, as native-born citizens are.

Qualitative methods should be used both to develop a hypothesis for further substudies and to investigate the following questions:

How do migrants and Germans experience primary care? Do the two groups have the same experiences?

What expectations do immigrants and Germans have of their primary care physicians?

Methods

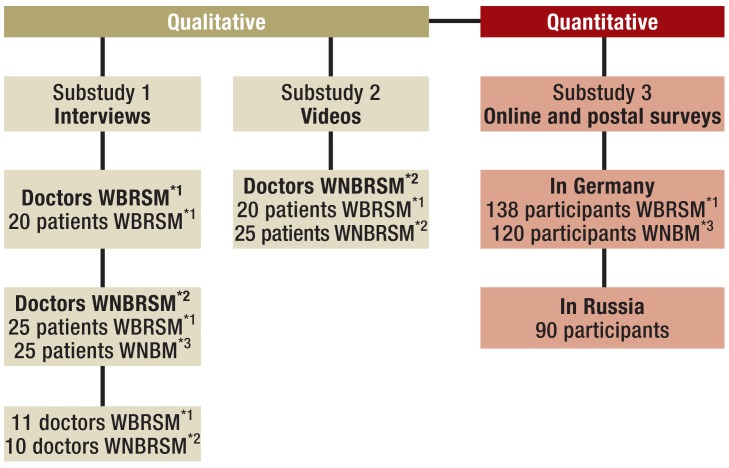

The work presented here concerns the primary care expectations and experiences of chronically ill patients with and without a background of Russian-speaking migration. It is part of a mixed methods study into the primary care received by Russian-speaking migrants (Figure) conducted at the Department of General Practice/Family Medicine at Philipps-Universität, Marburg (5, 6).

Figure.

Mixed methods design of the overall study “Russian-speaking patients of primary care physicians”. This article presents the results of the substudy that questioned patients receiving treatment from primary care physicians with no Russian-speaking background.

*1With background of Russian-speaking migration

*2With no background of Russian-speaking migration

*3Native-born Germans with no background of migration

Because the study concerns subjective perceptions and processing methods addressing a specific subject area, the problem-centered, semi-structured interview is the study method of choice (7).

Study conduct

Migrants were recruited via notices in Russian at locations frequently visited by them and according to the snowball principle. German participants were recruited both via the snowball principle and through their primary care physicians. The substudy presented here included only migrants receiving treatment from primary care physicians with no background of Russian-speaking migration. The presence of a chronic disease was an inclusion criterion, as this implies regular, usually long-term contact with a primary care physician, so patients’ views were based on multiple contacts with physicians.

Based on the existing literature and research questions, before the study a semi-structured guideline questionnaire was compiled containing open questions to determine primary care expectations and experiences, speculation on an ideal primary care physician, compliance, health-related behavior, and how well informed patients were about health-related issues. The guideline questionnaire served to delimit the subject area (Box). The questions were dynamically adapted to each item recounted by patients and integrated into the flow of patients’ answers.

Box. Extract from semi-structured guideline interview with example questions as aids for interviewer.

-

Migrants

History of migration

When did you arrive in Germany?

What was your experience of relocation?

First contact with German health care

Can you remember when you first needed a doctor in Germany?

What was your first impression?

Comparison of health-care systems

If you compare the German health-care system with that of your region of origin, what strikes you?

-

Germans

Experience and expectations: primary care physician

How long have you been receiving treatment from your primary care physician?

Have you ever switched primary care physicians? If so/not, why (not)?

What is your experience with treatment? What do you like? What do you dislike?

What is your idea of a perfect primary care physician?

How well informed are you about health-related issues? How do you get informed?

Interviews were held in the participants’ native language (either Russian or German), usually in participants’ homes. Conversations were recorded using an audio device, translated into German where necessary, and transcribed according to the transcription rules (8) in anonymized form. During the teamwork, the texts compiled in this way were coded according to a deductively and inductively devised coding system, using the software program MAXQDA, for qualitative content analysis (9). The members of the evaluation team (MV, VB, and SB) coded the top-level categories and subcategories independently of each other. Where necessary, codes were discussed within the team or in the qualitative research group of the Department of General Practice/Family Medicine at the University of Marburg.

Results

For reasons of space, we concentrate here on the categories that revealed the largest differences between the two groups, as this contributes more to understanding than the categories in which there were no differences.

Sample composition

The substudy participants were 25 migrants and 24 Germans (Table) from rural and urban regions of Hesse, Baden–Württemberg, and Lower Saxony in Germany.

Table. Composition of participant population.

| Migrants | Germans | |

|---|---|---|

| n = 25 | n = 24 | |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 13 | 15 |

| Male | 12 | 9 |

| Average age (years) | 53.5 | 60.4 |

| Occupational status | ||

| Working | 16 | 5 |

| Studying | 0 | 2 |

| Retired/unfit to work | 9 | 17 |

| Unemployed | 0 | 1 |

| Country of origin | ||

| Kazakhstan. Kyrgyzstan | 12 | – |

| Russia. Ukraine. Moldova | 13 | – |

| Time spent in Germany | 14.4 years (±3.9) | – |

| Age on arrival in Germany | 39.4 years (±15) | – |

Satisfaction with primary care physician

Both groups are satisfied with their current primary care physicians in terms of specialist skills, personal characteristics, and how the practice is organized. The differences are that, despite these similarities, Germans are mostly “very satisfied” with their primary care physicians. German_131210: “[…] it couldn’t have been better.” Migrants’ statements are usually more reserved and less exuberant. The doctor is often rated as “fine” or simply “OK.” Migrant_200310: “He’s good, he’s fine.” The participant groups differed in terms of the behavior they expected of physicians when obtaining information. Migrants believe that the physician “should dig for information.” Accordingly, the duty to obtain information lies with the physician. Migrant1_050310: “With him it’s you that tell him about your illness, not him that finds out about it. […] People don’t ask me questions and I don’t ask them.” Germans are of the opinion that the patient has a duty to provide information, to tell the doctor what may be important. German_020: “… and I thought, because it’s silly to leave out what you think, that it might be something else because maybe he hasn’t thought of something the way I still see it now, then we’ll talk about it.”

Difficulties encountered

With only a few exceptions, Germans mostly report that they do not experience any difficulties with doctor–patient contact. In contrast, approximately three-quarters of migrants report encountering multiple problems during contact with their primary care physicians.

Language-related problems are the most commonly cited issue. Migrants highlight that they are anxious that they may not be able to express themselves properly and that their concerns may not be understood. None of the participants report not understanding his or her physician. Migrant_100809: “[…] I was really worried I wouldn’t be able to explain what my symptoms were or what was the matter. […] kind of worried about the conversation, that I sort of wouldn’t be able to express things properly, that I wouldn’t be able to explain properly when he started asking questions.”

While one in three migrants reported not having received treatment they wanted or thought was needed, this was the case for only one in seven Germans. The following specific examples were given:

Doctor not prepared to prescribe medications and treatments

Referral to specialized physician occurred too late

Inadequate prevention

Unsuccessful treatment

A feeling of not having been taken seriously.

Only migrants experienced their doctor and his/her behavior and approach as “very businesslike” and therefore impersonal. Here, the word “businesslike” is used not the sense of “professional” but negatively, meaning “distanced,” “worklike,” and “cold” as opposed to “human” or “open.”

Dissatisfaction with treatment had led 10 migrants and four Germans to switch doctors at least once. Migrant3_050310: “I said, ’But how am I supposed to live with the pain?’ Nothing. He’d already got up, and he [patted] me on the shoulder. ’Keep taking the pills.’ And that was it. I said, ’But they don’t help!’ And then I was in the corridor. That was it. I’m not going back to that doctor again.”

Ten Germans and four migrants had switched doctors for administrative reasons such as moving house, practice closure, or difficulty of access. German_141210: “But not because of the doctor, really only because of the system around him, because of his practice, you know? Because the nurses just couldn’t seem to get it together, but not because of the doctor, not at all.”

Not all dissatisfied patients switch doctors, however. Some are unable to do so because of the care situation in their area, others are resigned and do not think they will be able to find anyone better. Migrant_100809: “You know, judging by what I read in the papers and see on TV […] We decided not to look for anyone else. He’s OK professionally. He helps us (,) he does everything for us that depends on him. […] So we stayed with him. And personal touch or not, that ought to weigh on their conscience.”

Being informed about health-related issues

Most participants state that they are poorly informed about health-related issues. However, there are substantial differences between the groups in terms of how they explain their lack of information.

German patients give complexity and poor access to information or their own lack of interest as reasons. Migrants also state that they have a lower level of knowledge than the native population and that this is not taken into account or compensated for by doctors. Immigrants themselves say that they have too little preexisting knowledge to find their way around the system in Germany and to be able to identify and use their other options. They also find it difficult to obtain information as they are not used to doing so and encounter obstacles. Migrant_210110: “You have to ask: what am I entitled to, what can I do, what can’t I do? Plus there’s an idea here that you come across a lot: if you don’t ask, they won’t tell you. Well, you didn’t ask, so I didn’t tell you! I can’t read your mind! Perhaps he didn’t tell you for these reasons or those reasons, but very often it’s just if you don’t ask, they won’t tell you.”

Migrants see the duty to provide information as lying very clearly with the physician; if the physician does not provide any information, none can be obtained. Different patients have different views on why doctors do not provide information on their own initiative and why patients have to ask many questions. Some suspect the intention to save money on migrants. Migrant_180110: “[…] but with foreigners and émigrés there’s an attitude that it’s their own fault if they don’t know.”

Others believe that doctors are overworked and have no time to provide information. The responsibility for providing information does not lie with doctors alone, however. Insurers should contribute their part to ensuring that patients are comprehensively informed, in the patient’s native language if possible.

Discussion

Russian-speaking immigrants and Germans were interviewed about their primary care expectations and experiences. Although both groups have positive experiences in general and seem satisfied rather than dissatisfied, there are differences in how this satisfaction is expressed. Germans praise their primary care physicians, whereas migrants are more reserved.

This seems to be because migrants experience difficulties with doctor–patient contact more frequently than native-born citizens, which lessens their satisfaction. They worry that they will not be able to explain their concerns to their doctor properly and will therefore not be understood. As a result, migrants probably begin discussions with their physicians with a different level of anxiety than native-born citizens, which may cause doctor–patient interaction to unfold differently. This hypothesis, developed on the basis of the interviews, is currently being tested using video analysis of the consultations (Figure).

Furthermore, migrants report having switched doctors as a result of dissatisfaction with treatment more often than Germans. However, they do not report any specific experience of discrimination—as has been the case in other studies, for example (10)—so we presume that they do not receive different or worse treatment than native-born citizens. Nevertheless, migrants are used to a different medical culture than native-born citizens, as medical standards and guidelines in Germany are different than those in the former Soviet Union (11, 12). Accordingly, expectations molded by the culture of origin can differ from actual experience and lead to uncertainty or dissatisfaction. For example, on the basis of the data we were able to show that migrants expected a more paternalistic style of communication from their doctors. This attitude can affect doctor–patient interaction, in addition to the separate linguistic difficulties, and make it more difficult to establish a rapport, as the various parties have differing ideas of the roles involved. A further hypothesis based on this substudy, namely that doctors are held in higher regard in migrants’ country of origin than in their adopted country, should be investigated. Should this be confirmed, it would represent a difference between Russian-speaking and Turkish patients. The latter are the best researched patient group with a background of migration and their experience with German doctors is at least as positive as that of German patients (13).

In addition to sources of error such as lack of understanding or other terms for symptoms, the diagnosis process can also be hindered by patients’ passivity. According to Donner-Banzhoff and Hertwig (14), diagnosis occurs in two phases. In the “inductive foraging” phase, the patient reports his or her complaints freely. At this point the doctor develops hypotheses concerning the patients’ complaints. If the patient’s report is exhaustive, the “deductive inquiry” phase begins, during which the doctor tests his or her hypotheses. If the patient is passive, the first phase ends too soon, however, so important evidence for a diagnosis may be missing.

As a consequence for clinical care, we recommend open yet explicit questions. Patients should be encouraged to rephrase things more, as a lack of language knowledge often means patients do not know specific terms, so they may hold back information out of uncertainty. Decisions regarding treatment should be scrutinized critically, as physicians may otherwise be inclined to concentrate on only the most obvious diagnoses, for example, for reasons of time.

Migrants also more frequently report not having received necessary medical intervention. On the one hand, this indicates that they are poorly informed, as stated above; for example, they may not know which services can be prescribed by the doctor and which cannot. On the other hand, it indicates societally determined expectations. The literature contains evidence that migrants of Turkish origin are more convinced of the efficacy of drugs, and expect more pharmacological treatment, than Germans, for example (15, 16). Doctors who were questioned reported similar experiences of patients of Russian origin within our mixed methods study. At the same time, migrants often come with diagnoses that have no equivalents in their adopted country or are not confirmed following examination. Accordingly, no treatment is provided, which causes dissatisfaction among patients (12).

Both groups believe that they are not well enough informed about health-related issues, partly because of complexity and lack of information. This has also been reported by other authors (17). It is also clear that Russian-speaking migrants have a different understanding of doctor–patient roles. For example, in their eyes physicians have a duty to obtain information concerning treatment and a duty to provide information regarding health. Migrants therefore often adopt a more passive attitude than Germans, which may be due to the medical and sociopolitical attitudes prevalent in their countries of origin (18). The impression given is that German patients demand and receive more explicit information than immigrants. Remennick reports that in Israel, too, Russian-speaking migrants also have to learn to “be informed and take part” rather than “consume” (19). The level of education of the patients questioned had no effect on their evaluation of contact with physicians; this is also confirmed by the other studies (6, 20).

The differences found here show that societal norms in migrants’ countries of origin continue to play a major role even after a prolonged period in their adopted country. The old concepts of roles and behavior patterns persist for a long time and are experienced as difficulties in doctor–patient interaction. In our opinion, primary care physicians should be made aware of potential misunderstandings, and flexible behaviors that may differ from usual routine should be encouraged.

Key Messages. Russian-speaking migrants’ experience in primary care consultations.

Patients feel inadequately informed about health-related issues.

Even after long periods in their adopted country, communication preferences molded by the culture of origin continue to affect doctor–patient interaction.

Russian-speaking migrants are more prepared to switch primary care physician.

Russian-speaking migrants experience multiple difficulties during doctor–patient interaction that affect their satisfaction with treatment.

Russian-speaking migrants see the duty to obtain relevant information as lying with the physician.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Caroline Devitt, M.A.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.van Wieringen JC, Harmsen JA, Bruijnzeels MA. Intercultural communication in general practice (eng) Eur J Public Health [Internet] 2002;1:63–68. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/12.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gelzer D. Migrantinnen und Migranten in der hausärztlichen Sprechstunde. PrimaryCare. 2005;5:128–131. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gerlach H, Becker N, Abholz HH. Welche Erfahrungen haben deutsche Hausärzte mit Patienten mit Migrationshintergrund? Ergebnisse einer Fokusgruppendiskussion mit Hausärzten. ZFA. 2008;84:428–435. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bungartz J, Uslu S, Natanzon I, Joos J. Inanspruchnahme des Hausarztes durch türkische und deutsche Patienten - eine qualitative Studie. Z Allg Med. 2011;87:115–122. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirsch O, Donner-Banzhoff N, Bachmann V. Measurement equivalence of four clinical questionnaires in native-born Germans, Russian-speaking migrants, and native-born Russians. J Transcult Nurs. 2013;24 doi: 10.1177/1043659613482003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bachmann V, Teigeler K, Hirsch O, Bösner S, Donner-Banzhoff N. Comparing health-issues of Russian-speaking immigrants, Germans and Russians. International Journal of Migration, Health and Social Care; 2014 in press. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Witzel Andreas. The problem-centered interview. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum. Qualitative Social Research 2000 1 1, Art. 22. http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0001228. (last accessed 27 November 2014) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bohnsack R, Lüders C. Qualitative Sozialforschung. In: Reichertz J, editor. Opladen: Leske & Budrich; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mayring P. Weinheim und Basel: Beltz; 2002. Einführung in die qualitative Sozialforschung. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerlach H, Abholz H, Koc G, Yilmaz M, Becker N. „Ich möchte als Migrant auch nicht anders behandelt werden“: Fokusgruppen zu Erfahrungen von Patienten mit Migrationshintergrund aus der Türkei. ZFA. 2012;88:77–85. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Remennick LI, Shtarkshall RA. Technology versus responsibility, immigrant physicians from the former Soviet Union reflect on Israeli health care. J Health Soc Behav [Internet] 1997;3:191–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grabbe L. Understanding patients from the former Soviet Union. Fam Med [Internet] 2000;3:201–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uslu S, Natanzon I, Joos S. Das Image von Hausärzten aus Perspektive von Patienten mit und ohne türkischem Migrationshintergrund - eine qualitative Studie. Gesundheitswesen. 2014;76:366–374. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1357199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donner-Banzhoff N, Hertwig R. Inductive foraging: Improving the diagnostic yield of primary care consultations. European Journal of General Practice. 2013:1–5. doi: 10.3109/13814788.2013.805197. Early Online. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferber L, Köster I, Celayir-Erdogan N. Türkische und deutsche Hausarztpatienten. Erkrankungen, Arzneimittelerwartungen und Verordnungen - Gesundheitswesen. 2003;65:304–331. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-39542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sahlan S, Wollny A, Brockmann S, Fuchs A, Altiner A. Reducing unnecessary prescriptions of antibiotics for acute cough: Adaptation of a leaflet aimed at Turkish immigrants in Germany. BMC Fam Pract. 2008;9 doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-9-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herbert S. Patientenerwartung und Therapiefreiheit: Der Arzt in Fesseln - und der Patient im Abseits. Dtsch Arztebl. 2008;105:A1662–A1666. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamann J, Bieber C, Elwyn L, et al. How do patients from eastern and western Germany compare with regard to their preferences for shared decision making? Eur J Public Health. 2012;22:469–473. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckr112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Remennick LI, Ottenstein-Eisen N. Reaction of new Soviet immigrants to primary health care services in Israel. Int J Health Serv [Internet] 1998;3:555–574. doi: 10.2190/JL9E-XHH9-XC5Y-5NA4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kirkcaldy BD, Siefen RG, Merbach M, Rutow N, Brahler E, Wittig U. A comparison of general and illness-related locus of control in Russians, ethnic German migrants and Germans (eng) Psychol Health Med [Internet] www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=17510907. 2007;3:364–379. doi: 10.1080/13548500600594130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]