Abstract

Patient: Male, 34

Final Diagnosis: Intramuscular hemangioma of the masseter muscle

Symptoms: Swelling over parotid region

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: Clinical-Radiological work-up

Specialty: Radiology

Objective:

Rare disease

Background:

Hemangioma is a benign vascular proliferation. Intramuscular hemangiomas are rare, accounting for less than 1% of all hemangiomas, and occur normally in the trunk and extremities. Approximately 10–20% of intramuscular hemangiomas are found in the head and neck region, most often in the masseter muscles. The typical clinical characteristic is a painful soft tissue mass without cutaneous changes. Currently, MRI is the standard imaging technique for diagnosing soft-tissue hemangioma. The optimal management is the surgical resection.

Case Report:

We report a case of 34-year-old male patient consulted for a swelling of 1 year evolution, around the parotid region. On physical examination, a soft, well-contoured lesion of about 2 cm on its long axis was found. MRI showed a space-occupying lesion in the left masseter muscle, with intermediate signal intensity on T1-weighted images and hyperignal intensity on T2-weighted images, containing nodular hypointense foci corresponding to calcification. The presumptive diagnosis of an intramasseteric hemangioma with phlebolith was made based on these findings. The patient was informed about her condition, and treatment options were discussed; however, the patient elected to forgo treatment at that time.

Conclusions:

The possibility of an IMH should be included in the differential diagnosis of any intra-masseteric lesion. The appropriate radiologic examinations especially MRI can enhance accurate preoperative diagnosis; the treatment of choice should be individualized in view of the clinical status of the patient.

MeSH Keywords: Diagnostic Imaging, Hemangioma, Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Background

Intramuscular hemangiomas (IMHs) are very rare and constitute approximately 1% of all hemangiomas [1]; 0.8% of all hemangiomas and 10–20% of all IMH are located in the head and neck muscles, arising most frequently from the masseter and trapezius muscles [2].

IMHs generally present as progressively enlarging and often painful lesions. Thrills, bruits, compressibility, and pulsation are usually absent [3–5].

Preoperative diagnosis of IMH of the masseter muscle is problematic because they may be confused with parotid tumor or other muscular lesions. In a patient with a soft-tissue mass suspected of to be a hemangioma, MRIs may provide more specific information regarding the characteristics, origin, and extent of the lesion than other imaging modalities [6].

The present case report describes an IMH of the masseter muscle with phlebolith, highlighting the clinical presentation, the features evident in MRI, and the treatment options.

Case Report

A 34-year-old male patient, without medical or family history of interest, consulted for a swelling of 1-year evolution, located around the parotid region. On physical examination, a soft, well-contoured, oblong lesion of about 2 cm on its long axis was found around the left parotid region. No bruit or thrill was apparent. Facial move ments, intraoral examinations, and overlying skin were normal.

The maxillofacial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a circumscribed lesion, slightly hyperintense to the masseter muscle and hypointense to the parotid gland on T1-weighted images (Figure 1), markedly hyperintense to both the masseter muscle and parotid gland on T2-weighted images (Figure 2), with a rounded area of signal hypointensity on both T1 and T2-weighted images corresponding to calcification, intensely enhanced on contrast-enhanced T1-weighted images (Figure 3).These findings were strongly suggestive of an IMH of the masseter muscle with phlebolith.

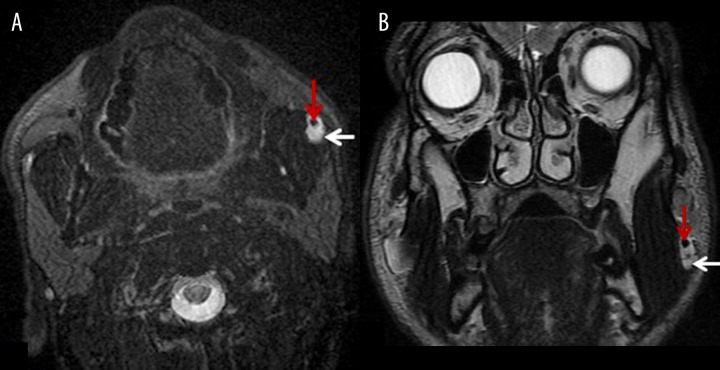

Figure 1.

Axial T1-weighted MRI showing a lesion in the anterior portion of the left masseter muscle (white arrow). The signal intensity is slightly higher than in the muscle.

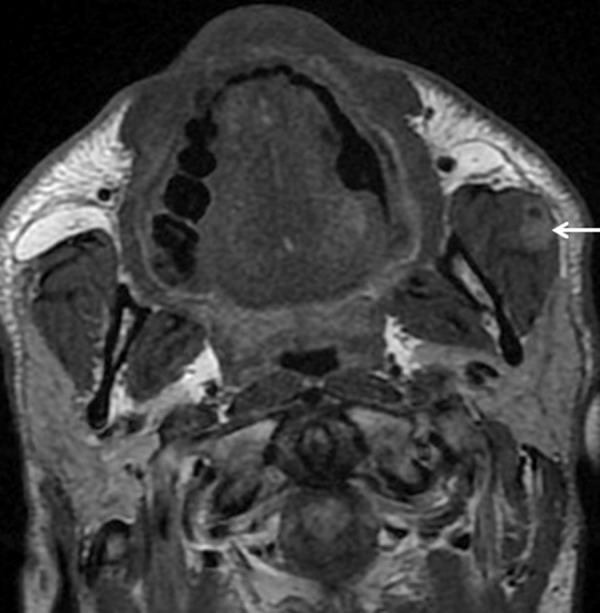

Figure 2.

Axial T2-weighted fat saturated image (A) and coronal T2-weighted image (B) show a well-circumscribed, hyperintense lesion in the anterior portion of the left masseter muscle (white arrow). There are hypointense areas within the lesion (red arrow).

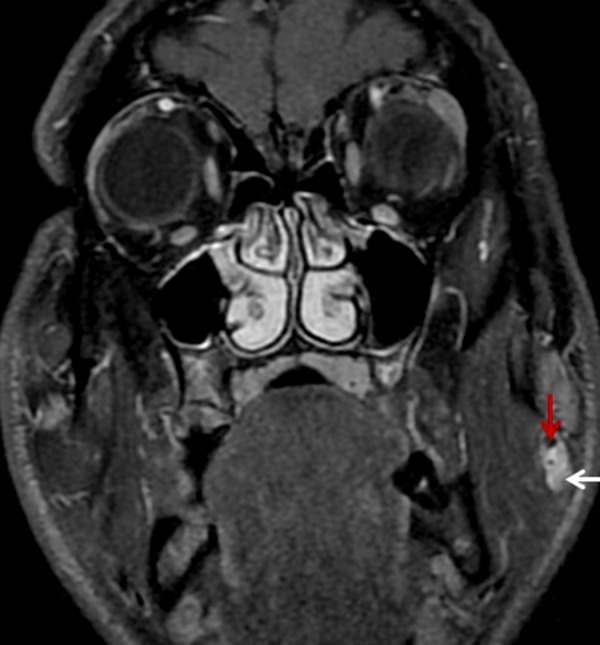

Figure 3.

Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted images showing a marked enhancement of the intra-masseteric lesion (white arrow), except for the rounded area of signal hypointensity, which corresponds to a calcification (red arrow).

The patient was informed about his condition, and treatment options were discussed; however, the patient elected to forgo treatment at that time.

Discussion

IMHs are very rare, benign tumors of vascular origin, accounting for less than 1% of all hemangiomas [1], and less than 20% of these are found in the head and neck area [2,7]. The masseter muscle is the most frequent muscle involved, accounting for 5% of all IMHs. The trapezius, periorbital, sternocleidomastoid, and temporalis muscles follow the masseter muscle in frequency. The tongue, extra-ocular, and posterior neck muscles have also been reported to be involved with hemangioma, with less frequency. [7]

IMHs are most commonly seen among adolescents and young adults, especially before the age of 30; however, they may affect older patients [1,2]. Although IMH have shown an equal sex distribution, involvement of the masseter has a definite male predominance [8]. It has been suggested that they arise from malformed tissue that has been subjected to repeated trauma or are the result of hormonal factors [9]. IMHs progressively enlarge but never metastasize [10].

IMHs generally present as progressively enlarging and often painful lesions. Because of their deep location, they rarely display any clinical signs or symptoms that suggest a vascular nature, such as pulsations, thrills, or bruits. Overlying skin discoloration is also uncommon. The absence of pathognomonic clinical findings and the rare incidence of these lesions make accurate pre-operative diagnosis difficult [3,4] and only 8% of all cases of IMHs are diagnosed before surgical intervention [11] (this was noted in 1957; advances in investigative techniques may have altered this figure). A variety of muscle neoplasms, benign muscular hypertrophy, congenital cysts, and lymphadenopathies are commonly confused in differential diagnosis [4].

These neoplasms appear to grow as non-encapsulated masses characterized by a multicentric proliferation of cords of endothelial cells that subsequently canalize. The characteristic of locally invasive tumor involved growth along planes of least resistance. It is confined to a single muscle in 80% of cases [12]. Histologically, the lesions are classified as capillary (vessels smaller than 140 micrometers in diameter), cavernous (vessels larger than 140 micrometers in diameter), or mixed [12]. Capillary hemangioma is the most frequent hemangioma, located in the cutaneous or subcutaneous tissues and diagnosed in the first decade of life. Most instances of capillary hemangioma undergo involution spontaneously. Cavernous hemangiomas are large and deeply located and are diagnosed later in life; these lesions are frequently intramuscular, do not have spontaneous involution, and require surgical treatment. Mixed hemangioma is, microscopically, a mixture of capillary and cavernous hemangioma [13].

For preoperative diagnosis of IMHs, plain radiographs, CT scan, MRI, and angiography may be helpful.

Plain radiography occasionally demonstrates phleboliths within the lesion. According to ultrasound examina tions, there was a heterogeneous, echogenic, cystic mass with posterior acoustic shadowing secondary to the calcified nodular areas [7,12]. With non-enhanced CT, an ill-defined mass of similar attenuation to muscle may be identified. Phleboliths too small to identify on radiographs can be revealed. After administration of contrast material, significant enhancement is typical [13]. Currently, MRI is the standard imaging technique for diagnosing soft-tissue hemangioma [13]. On T1-weighted images, compared with muscle tissue, intensities of the lesions are isointense or hyperintense with unclear margins [14]. On T2-weighted images, hemangiomas are typically hyperintense and have clear margins and lobulated contours [14,15]. Marked hyperintensity of the lesions on T2-weighted images is due to increased fluid content secondary to stagnant blood flow in large vessels [9,14–16]. Hemorrhagic and calcified areas and fatty tissue located in the hemangioma are responsible of heterogeneous signal intensity on T1- and T2-weighted sequences. Punctuate or reticular low sig nal intensity areas represent fibrous tissue, fast flow within the vessel, or foci of calcifications. Phleboliths appear as circular areas of low signal intensity [14,15]. If gadolinium contrast material is administered, prominent enhancement of the tumor is expected [13].

In our case, MRI findings were identical with the literature and our cases have characteristic signs for hemangioma-like high signal intensity on T2-weighted MRI images, with marked enhancement after gadolinium administration and phlebolith.

Angiography is another imaging modality and may delineate the vascular nature of an IMH and the feeding artery [7,12].

Management of IMHs should be individualized according to the size and anatomic accessibility of the tumor, its growth rate, age of the patient, and cosmetic and functional considerations [17]. Many forms of therapy have been suggested, including steroid injections, radiation therapy, injection of sclerosing agents, cryotherapy, and electrocoagulation. However, the optimal management is surgical resection with wide margins of surrounding normal muscle because of the infiltrative nature of IMHs [18]. Even with this approach, local recurrence rates ranging from 9% to 28% have been reported [12].

In our case, the patient was informed about his condition and treatment options were discussed; however, he elected to forgo treatment at that time.

Conclusions

The possibility of an IMH should be included in the differential diagnosis of any intra-masseteric lesion. Appropriate radiologic examinations, especially MRI, can enhance accurate preoperative diagnosis; the treatment of choice should be individualized in view of the clinical status of the patient.

References:

- 1.Fletcher CD, Unni KK, Mertens F, editors. Pathology and genetics of tumors of soft tissue and bone. Lyon: IARC Press; 2002. World health organization: Classification of tumors. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weiss SW, Goldblum JR. Benign tumors and tumor-like lesions of blood vessels. In: Weiss SW, Goldblum JR, editors. Enzinger and Weiss’s soft tissue tumors. 4th ed. St. Louis: C.V. Mosby; 2001. pp. 837–90. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Avci G, Yim S, Misirliogolu A, et al. Intramasseteric hemangioma. Plast Reconst Surg. 2002;109:1748–49. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200204150-00055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Demir Z, Oktem F, Celebioglu S. Rare case of intramasseteric cavernous hemangioma in a three-year-old boy: a diagnostic dilemma. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2004;113:455–58. doi: 10.1177/000348940411300607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barnes L. Tumors and tumor like lesions of the soft tissue. In: Barnes L, editor. Pathology of the head and neck. New York: Marcel Dekker; 2001. pp. 900–1. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee SK, Kwon SY. Intramuscular cavernous hemangioma arising from masseter muscle: a diagnostic dilemma (2006: 12b) Eur Radiol. 2007;17(3):854–57. doi: 10.1007/s00330-006-0448-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rossiter JL, Hendrix RA, Tom LW, Potsic WP. Intramuscular hemangiomas of the head and neck. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1993;108:18–26. doi: 10.1177/019459989310800103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoehn JG, Farrow GM, Devine KD. Invasive Hemangioma of the Head and-neck. Am J Surg. 1970;120:495–98. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(70)80014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zengin AZ, Celenk P, Sumer AP. Intramuscular hemangioma presenting with multiple phleboliths: a case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2013;115(1):e32–36. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2012.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones KG. Cavernous haemangioma of striated muscle – a review of literature and a report of four cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1953;35-A(3):717–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scott JES. Haemangiomata in skeletal muscle. Br J Surg. 1957;44:496–501. doi: 10.1002/bjs.18004418713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolf GT, Daniel F, Arbor A, Krause CJ. Intramuscular haemangioma of the head and neck. Laryngoscope. 1985;95:210–13. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198502000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olsen KI, Stacy GS, Montag A. Soft-tissue cavernous hemangioma. Radiographics. 2004;24:849–54. doi: 10.1148/rg.243035165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vilanova JC, Smirniotopoulos JG, Perez-Andres R, et al. Hemangioma from head to toe: MR imaging with pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2004;24:367–85. doi: 10.1148/rg.242035079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bayaroğulları H, Çokkeser Y, Akbay E, et al. Intramuscular cavernous hemangioma. J Clin Exp Invest. 2012;3(3):404. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kanaya H, Saito Y, Gama N, et al. Intramuscular hemangioma of masseter muscle with prominent formation of phleboliths: A case report. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2008;35:587–91. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Terezhalmy GT, Riley CK, Moore WS. Intramuscular hemangiomas. Quintessence Int. 2000;31(2):142–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ichimura K, Nibu K, Tanaka T. Essentials of surgical treatment for intramasseteric hemangioma. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1995;252:125–29. doi: 10.1007/BF00178096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]