Abstract

Thyroid hormone (T3) affects adult metabolism and postembryonic development in vertebrates. T3 functions mainly via binding to its receptors (TRs) to regulate gene expression. There are 2 TR genes, TRα and TRβ, with TRα more ubiquitously expressed. During development, TRα expression appears earlier than T3 synthesis and secretion into the plasma. This and the ability of TRs to regulate gene expression both in the presence and absence of T3 have indicated a role for unliganded TR during vertebrate development. On the other hand, it has been difficult to study the role of unliganded TR during development in mammals because of the difficulty to manipulate the uterus-enclosed, late-stage embryos. Here we use amphibian development as a model to address this question. We have designed transcriptional activator–like effector nucleases (TALENs) to mutate the TRα gene in Xenopus tropicalis. We show that knockdown of TRα enhances tadpole growth in premetamorphic tadpoles, in part because of increased growth hormone gene expression. More importantly, the knockdown also accelerates animal development, with the knockdown animals initiating metamorphosis at a younger age and with a smaller body size. On the other hand, such tadpoles are resistant to exogenous T3 treatment and have delayed natural metamorphosis. Thus, our studies not only have directly demonstrated a critical role of endogenous TRα in mediating the metamorphic effect of T3 but also revealed novel functions of unliganded TRα during postembryonic development, that is, regulating both tadpole growth rate and the timing of metamorphosis.

Thyroid hormone (T3) affects diverse biological processes including vertebrate development, organ metabolism, and diseases. The effect of T3 is believed to be mostly mediated by T3 receptors (TRs). TRs belong to the superfamily of nuclear hormone receptors, which also includes steroid hormone receptors and 9-cis retinoic acid receptors and mainly function as heterodimers with 9-cis retinoic acid receptors to bind to T3 response elements (TREs) in T3-inducible genes constitutively (1–9). TRs repress their expression in the absence of T3 and activate them when T3 is available by recruiting corepressors and coactivators, respectively (6, 10–16). These dual functions suggest that both unliganded and T3-bound TRs affect normal and pathological processes in vivo.

There are 2 known TR genes, TRα and TRβ, in vertebrates. Of the 2, TRα is more ubiquitously expressed. TRα is expressed before the maturation of the thyroid gland during vertebrate development (17–22). Thus, it is likely that unliganded TRα regulates T3 response genes to affect early vertebrate development. Consistently, although T3 deficiency leads to severe developmental defects and lethality in mouse, TR knockout mice have much milder phenotypes (23–25). However, direct evidence for a role of unliganded TR during mammalian development has been difficult to obtain because the embryos are enclosed in the uterus and dependent on the maternal supplies of nutrients, making it difficult to manipulate T3 levels during postembryonic development.

Amphibian development serves as an excellent model to study TR function in vivo (6, 17, 26–28). Anurans such as the highly related species Xenopus laevis and Xenopus tropicalis undergo a biphasic developmental process. Their embryogenesis produces a free feeding tadpole in the absence of T3. Subsequently, as endogenous T3 becomes available, the tadpole is transformed into a frog in a metamorphic process that changes essentially every organ/tissue of the animal (17, 26). Importantly, this process is totally dependent on T3. It can be easily induced or blocked by addition of T3 or T3 synthesis inhibitors, respectively, into tadpole-rearing water (26). Furthermore, earlier studies in X. laevis have suggested that TR is necessary and sufficient to mediate the metamorphic effects of T3 (29–42). In addition, as in mammals, TRα expression in X. laevis and X. tropicalis is activated early, reaching high levels by the end of embryonic development when a free-feeding tadpole is formed, well before the onset of metamorphosis at stage 54 (8, 43, 44). This observation has led us to propose a dual function model for TR during Xenopus development (45, 46). That is, unliganded TR binds to T3 response genes and regulates their expression (repression for T3-induced genes and activation for T3-repressed genes) to prevent precocious metamorphosis in premetamorphic tadpoles. When T3 becomes available either endogenously during metamorphosis or through exogenous addition to the rearing water of premetamorphic tadpoles, unliganded TR then activates the T3-induced genes or represses the T3-repressed genes, leading to tadpole metamorphosis. In support of this observation, chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays have shown that TR binds constitutively to the promoter regions of T3-induced genes in premetamorphic tadpoles (30, 31). On the other hand, direct evidence for a role of unliganded TR in postembryonic development has been lacking.

Here, we have made use of the recent advance in transcriptional activator–like effector nuclease (TALEN)–mediated in vivo gene mutation technology to investigate the role of unliganded TRα in X. tropicalis, a diploid species highly related to X. laevis (44, 47–50). We show that TRα-specific TALENs can specifically mutate the endogenous TRα gene with >90% efficiency upon expression in fertilized eggs, thus producing essentially TRα knockout animals. Importantly, TRα knockdown tadpoles are resistant to T3 treatment, suggesting that TRα is the predominant or major TR in premetamorphic tadpoles. Such animals also have reduced TR binding to endogenous T3 target genes and delayed metamorphosis. More importantly, the knockdown of TRα enhances the growth and development of premetamorphic tadpoles, accompanied by increased GH gene expression. Morphology analyses suggest that TRα knockdown animals have more advanced development, initiating early metamorphic changes with no or little endogenous T3, compared with that of the wild-type siblings. Thus, our results indicate that unliganded TRα plays a role in controlling the timing of frog metamorphosis and that TRα is also important for mediating the metamorphic effects of T3.

Materials and Methods

Animal rearing and staging

All animal care and treatments were done as approved by the Animal Use and Care Committee of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health. Adult X. tropicalis were purchased from NASCO. Embryos were staged according to the description for X. laevis (51).

Embryos were reared in 0.1× Marc's modified Ringers solution (MMR) in agar-coated Petri dishes for 3 days at 25°C and then were transferred to a ≥1 L container. Different groups of tadpoles were reared at similar densities. Tadpoles were anesthetized with MS222 for photography and body length measurement.

TALEN assembly and TALEN mRNA preparation

The backbones of TALEN left arm and right arm derived from Refs. 52 and 53 were subcloned into a double promoter transgenesis construct (54) with green fluorescent protein and red fluorescent protein driven by the γ-crystallin promoter. A TALEN pair targeting X. tropicalis TRα was assembled as described previously (52, 53, 55).

The TRα TALEN left arm (TRα-L) recognizes the sequence 5′-ACATCCCCAGCTATCT-3′ and the TRα TALEN right arm (TRα-R) recognizes the sequence 5′-ATCACTGCACACCACACAC-3′ in the coding region, both in exon 3 of the X. tropicalis TRα. A control TALEN pair consisted of the TALEN-L (control-L) recognizing 5′-GAAAAACTCAACAA-3′ and the TALEN-R (control-R) recognizing 5′-TCTCCATAGACCTCA-3′ in an unrelated gene.

To generate the TALEN mRNA in vitro, the individual TALEN plasmid was linearized with NotI. Capped RNA was synthesized by using the linearized DNA and Ambion in vitro transcription kit. After removing the DNA template by DNaseI digestion, capped RNA was purified with an RNeasy kit (QIAGEN).

Embryo injection

Mature adult X. tropicalis frogs were primed with 20 U of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) (Novarel) 1 day before the experiment. The injected frogs were boosted with 200 U of hCG on the second day. Just before the females started to lay eggs, the male was killed to obtain the testes. One testis was smashed to prepare a sperm suspension in 300 μL of 1× MMR. For in vitro fertilization, freshly squeezed eggs from a hCG-injected female were mixed with the sperm suspension for about 2 minutes. The sperm in the mixture were then activated by diluting the mixture to 0.1× MMR. The fertilized eggs were dejelled in 3% cysteine solution, pH 8.0. After washing with 0.1× MMR several times, the fertilized eggs were placed in an agar-coated plate. For TALEN mRNA injection, equal amounts of TALEN-L and TALEN-R mRNAs were mixed and injected into the fertilized egg at 400 pg for each mRNA per egg with a Drummond Nanoject II Auto-Nanoliter Injector. The embryo injection was done at least 3 times with similar results.

Detection and screening for TALEN-induced mutations

Three or more embryos from the same group were pooled together and lysed with the lysis buffer (10 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM EDTA, and 0.5% SDS [pH 8.0]) containing 8 μg/mL proteinase K (Roche) at 56°C overnight. Genomic DNA was precipitated with 500 μL of isopropanol, washed with 70% ethanol twice, dried in the air, and dissolved in 10 mM Tris (pH 8.0). A DNA fragment encompassing the 2 TALEN-recognized regions of the TALEN pair was amplified by using primers F (5′-ATTGGGTTGGTTGTGGGTCG-3′) and R (5′-TAAGGTGGGGGCAGTACAGG-3′) and cloned into the pCR-TOPO T vector. Preliminary screening of mutant bacterial colonies was carried out by using colony PCR with primers R, f (5′-ATGTTCCATGAGACGCCCCT-3′), and f1 (5′-CCAGCTATCTGGACAAAGAC-3′), whose 3′-end lies in the middle of the region targeted for cleavage by the TALEN. Mutant colonies thus identified were verified by sequencing.

RNA extraction and quantitative RT-PCR

Three or more tadpoles were homogenized together in TRIzol, and total RNA was isolated (Invitrogen). RT was performed by using the QIAGEN QuantiTect RT kit. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed by using the Cyber Green method with the following primers: forward primer 5′-CTCTAGCAGCTGATGGTGGG-3′ and reverse primer 5′-TGGGTTTTGTTCCTGGTGCT-3′ for TRβA (NM_001045805); forward primer 5′-GGCACAGGTGTCCTTATGCT-3′and reverse primer 5′-AAGGGCGTTCACCTGTATGG-3′ for klf9 (NM_001113674); forward primer 5′-CCAAGGGAAACGGGTGGCTT-3′ and reverse primer 5′-GTGCCACCTCTGCGGAAAGT-3′ for TH/bZIP (XM_004918906); forward primer 5′-AAGAGGGATCTGGCAGCGG-3′ and reverse primer 5′-AAGGACACCAGTCTCCACAC-3′ for EF1α (BC157768); forward primer 5′-CAAGCCCTGAGCAAAGTGTTC-3′ and reverse primer 5′-TTCCATCTTCCAACTCCCGC-3′ for GH1 (XM_002933042); forward primer 5′-AAACATTCCCGCTCCGACAG-3′ and reverse primer 5′-AGGGTCAGTGAGTACCGCAA-3′ for GH2 (XM_002934063); and forward primer 5′-AAATGCATTGCCGTTGGCAT-3′ and reverse primer 5′-GCCGCTCTCGATTCTCTTCA-3′ for TRα (NM_001045796). The studies were done at least twice with similar results.

ChIP assay and quantitative PCR

Three or more tadpoles were homogenized for ChIP assay as described previously with anti-TR and anti-Id14 antibodies as a negative control (50, 56) (Table 1). The immunoprecipitated DNA was analyzed by using TaqMan quantitative PCR with the gene-specific primers/probes for TRβA promoter, TH/bZIP promoter, and exon 5 of TRβA as described previously (31).

Table 1.

Antibodies

| Peptide/Protein Target | Antigen Sequence (If Known) | Antibody Name | Manufacturer and Catalog No. or Source of Antibody | Species Raised in | Dilution Used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ID14 | DKVTPKKDDGATS-KLH, ETKCRCNMDGDVE-MAP | Anti-ID14 | Refs. 50, 56 | Rabbit polyclonal | 1:100 |

| TR | Recombinant xlTRb protein | Anti-TR | Refs. 44, 50, 56 | Rabbit polyclonal | 1:100 for ChIP, 1:1500 for Western blot |

| Histone H3 | Residues 100 to the C terminus of human histone H3 | Anti-H3 | Abcam, ab1791 | Rabbit polyclonal | 1:5000 |

Isolation of nuclear proteins and Western blot

Three or more tadpoles, after removal of the digestive tract filled with food debris, were pooled together and homogenized with a Dounce homogenizer. The isolation of the nuclear proteins was carried out according to the instructions for the NE-PER Nuclear Protein Extraction Kit (Thermo Scientific). The nuclear protein samples were subject to Western blot analysis with 1:1500 dilution of anti-TR antiserum (44) and 1:5000 dilution of anti-H3 antibody (Abcam), which served as a loading control. The analysis was done twice with similar results.

Results

Efficient mutation of the TRα gene upon expressing a TRα TALEN in X. tropicalis embryos

To investigate the role of TRα during Xenopus development, we generated a TRα-specific TALEN made of 2 arms targeting exon 3 of the X. tropicalis TRα gene (Figure 1) as described previously (52, 55). The plasmid DNA containing each arm was transcribed in vitro to prepare capped mRNAs encoding the TRα TALEN arms (TALEN TRα-L or -R, for the left and right arm, respectively). In addition, control mRNAs encoding the left and right arm (TALEN-L and -R) of an unrelated gene were also prepared similarly. The mRNAs were injected in various combinations, both TALEN TRα-R and -L mRNAs or one TALEN TRα arm and one control TALEN arm into fertilized X. tropicalis eggs. After 3 days of development at 25°C, fertilized eggs developed into feeding tadpoles (around stage 45), and there was no observable difference among animals without or with the injection of different mRNA combinations at this age (Supplemental Figure 1).

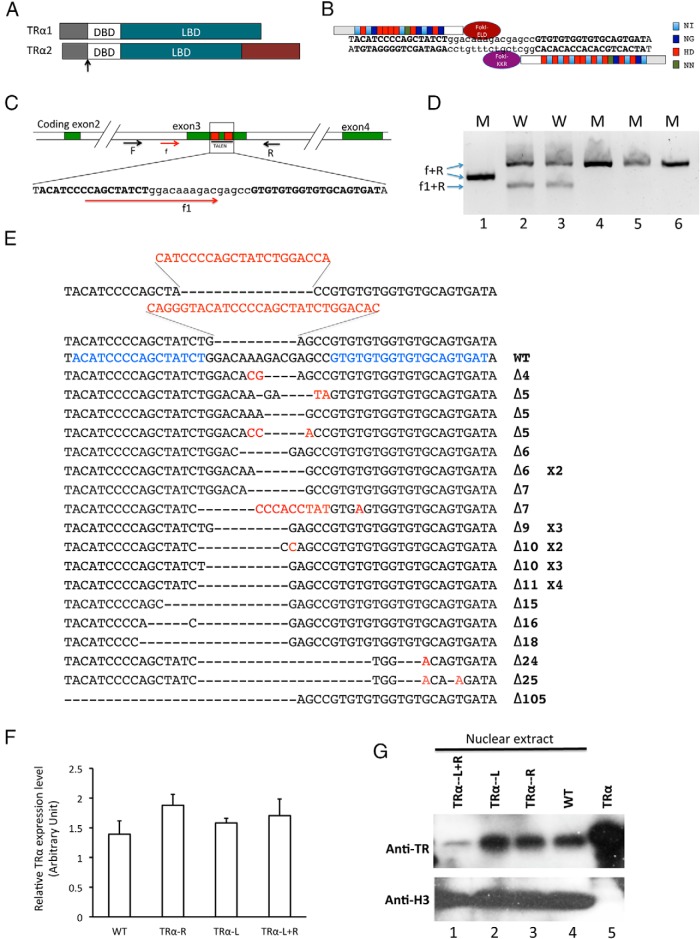

Figure 1.

Expression of TRα TALEN leads to mutations in the TRα gene in X. tropicalis embryos. A, Schematic diagram depicting 2 TRα isoforms due to alternative splicing. DBD, DNA-binding domain; LBD, ligand-binding domain; black arrow, TALEN target region. B, Schematic representation of the TRα TALEN and the targeted DNA sequence in the TRα gene in X. tropicalis. The 4 types of repeat variable di-residues) recognizing nucleotide A, G, T, or C are depicted in different colors. The left arm contains the FokI-ELD nuclease and the right arm contains the FokI-KKR nuclease, which, when both arms bind to their respective binding sites, heterodimerize to form the functional nuclease to make a double-stranded break in the intervening sequence. C, Schematic diagram of the TRα gene showing the TALEN target site and the primers used for mutant screening. The protein coding exons are shown as numbered, colored boxes. The TALEN-recognized sequences are shown as red boxes (top) or blue letters (below). Arrows represent primers. F and R were used for amplification of genomic DNA. Primers f, R, and f1 were used for colony PCR screening of mutations. Mutations in the target region between the 2 TALEN-recognized sequences would reduce the PCR efficiency when f1/R primers are used but would not affect the PCR with f/R primers. D, Representative PCR results from wild-type and mutant colonies. The bacterial colonies were directly PCR amplified with primers f/f1/R. The wild-type colonies produced 2 bands due to PCR amplification by f/R and f1/R, respectively (lanes 2–3). However, for the mutants, only the larger band, ie, from f/R amplification, was seen, suggesting that the presence of a mutation(s) affected the amplification by f1/R (lanes 1, and 4–5). Note that in lane 1, the f/R band was noticeably smaller than in the other lanes because of the large deletion in this mutant (sequencing of the colony revealed that it had a 105-bp deletion, the last sequence in Figure 1E). M, mutant colony; W, wild-type colony. E, TRα TALEN induces mutations in the TRα gene. TALEN-injected embryos were used for PCR cloning of the target region in the TRα gene, and individual mutant clones as identified above were sequenced. The sequences from mutant clones were aligned with the wild-type sequence (WT). Characters in red indicate nucleotide changes from the wild-type sequence. Dashes represent nucleotide deletions. The TALEN-recognized DNA sequences are shown in blue. The X2 to X4 shown on the right of 5 mutant sequences indicate 2 to 4 independent clones having the corresponding sequences, respectively. The number after Δ on the right indicates the number of nucleotides that were deleted in the mutant compared with that in the wild type. The 2 sequences above the WT are 2 mutant clones with deletions and insertions in the targeted region. F, TALEN expression does not affect the total level of TRα mRNA. A set of primers far away from the TRα TALEN–targeted region was used for analysis of the TRα mRNA level in the control and TRα knockdown groups. WT, no TALEN mRNA injection; TRα-R, injected with TRα TALEN-R and control-L mRNAs; TRα-L, injected with TRα TALEN-L and control-R mRNAs; TRα-L+R, injected with TRα TALEN-L and -R mRNAs. Note that, as expected, there was no significant difference in the TRα mRNA levels between the control and TALEN-injected groups. G, TALEN expression specifically reduces the TRα protein level. Nuclear proteins were isolated from pooled wild-type and various TALEN-injected animals (see F for more information). Western blot analyses were performed to determine the levels of TRα and histone H3 (loading control). Lane 5 shows the in vitro translated X. tropicalis TRα protein as the positive control (44).

To determine whether the expression of the TRα TALEN caused any mutation of the endogenous TRα gene, a DNA fragment flanking the region targeted by the TRα TALEN was amplified by PCR from genomic DNA isolated from whole tadpoles with or without the injection of various TALEN mRNAs. The PCR fragment was cloned, and individual bacterial colonies were PCR analyzed with nested primer pairs (Figure 1C). One of the primer pairs (f/R) was located outside the TALEN targeted region, whereas the second one (f1/R) had a primer (f1) whose 3′-end was located within the targeted region. Mutations/deletions in the targeted region thus would probably affect the PCR amplification efficiency by f1/R, resulting in a reduced amount of PCR product from the mutant colonies compared with that from the wild type. On the other hand, the amplification with the f/R should be independent of TALEN-generated mutations/deletions. Figure 1D showed representative results from wild-type and mutant colonies. Some mutant colonies were subsequently sequenced and found to indeed contain mutations/deletions in the TALEN-targeted region (Figure 1E). Importantly, colony PCR analyses revealed that 2 days after TALEN mRNA injection, 75% of the colonies (15 of 20) in the group injected with both TALEN TRα-R and -L mRNAs were mutants, and after 3 days (around stage 45, the feeding stage), the mutant colonies accounted for >95% of the colonies (26 of 27), ie, >95% of the TRα locus had mutations in TRα TALEN–injected animals. In contrast, at 3 days of age, no mutant colonies were obtained when the TRα region was PCR amplified from genomic DNA of animals injected with mRNAs encoding either the TRα TALEN left arm and a nonspecific TALEN right arm (0 of 16) or a TRα TALEN right arm and a nonspecific TALEN left arm (0 of 14). Thus, the TRα TALEN was very effective and specific in causing mutations/deletions in the endogenous TRα gene during embryogenesis.

We next investigated whether TRα TALEN expression altered TRα expression. First, we analyzed TRα mRNA levels in the control and TALEN-injected animals by using quantitative RT-PCR on total tadpole RNA with a primer pair located outside the TALEN targeted region. The results showed that TALEN expression did not alter TRα mRNA levels (Figure 1F). This was expected because the TALEN-induced mutations/deletions only affected a small part of the coding region that should not affect TRα promoter. We then analyzed TRα protein. Because the level of TRα proteins during development are too low to be detected by using total cellular extract (57), we isolated the nuclear proteins for Western blot analysis. The results showed a drastic reduction in the TRα protein level in the tadpoles injected with both arms of the TRα TALEN but not in animals injected with only one of the TRα TALEN arms (Figure 1G). The findings were consistent with the fact that tadpoles injected with both TRα TALEN arms had high levels of deletions in the TRα locus, two-thirds of which were expected to be out-of-frame changes that would prevent the translation of the TRα protein. Thus, TRα TALEN expression resulted in significant knockdown of TRα protein expression.

TRα knockdown leads to T3 resistance in premetamorphic tadpoles.

Xenopus embryogenesis is essentially independent of T3 and TR because there is little T3 and TR in eggs and during embryogenesis (8, 29, 43, 45, 58, 59). Thus, it was not surprising that despite the effective knockdown of TRα in early embryos, embryogenesis was apparently normal, leading to the formation of normal feeding tadpoles even in the presence of various combination of injected TALEN mRNAs (Figure 2A and Supplemental Figure 1). As indicated in the Introduction, earlier studies have led to a dual function model for TR during Xenopus development. The ability to generate TRα knockdown tadpoles allowed us, for the first time, to directly test this model. Premetamorphic tadpoles as early as stage 45, the onset of feeding, can respond to exogenous T3 to undergo premature metamorphosis (60). To investigate the role of TRα in this process, we treated tadpoles around stage 48 with 10 nM T3 for 5 days and analyzed the response of the tadpoles to T3. As expected, wild-type tadpoles responded to the treatment by undergoing precocious metamorphosis, most noticeably gill resorption and reshaping of the jaws, becoming pointy (Figure 2A). In addition, T3 treatment led to the cessation of feeding and the treated animals were also smaller than the untreated control animals (Figure 2A). The same response was observed for animals injected with the mRNAs for one of the TRα TALEN arms plus one of the control arms (Figure 2A, TRα-R or TRα-L group). In contrast, when mRNAs for both arms of the TRα TALEN were injected into the fertilized eggs, the resulting tadpoles were resistant to T3 treatment (Figure 2A, TRα-L+R). Most of these knockdown animals had essentially no T3-induced morphological changes (Figure 2A, right column). Whereas some animals did show some reduction in gills and change in the shape of the jaws (Figure 2A, middle column), these changes were much less obvious that those in the wild-type or control TALEN–injected animals. On the other hand, these knockdown tadpoles were still smaller than those before T3 treatment (Figure 2A, TRα-L+R, compared with the no T3 to T3 columns). Thus, TRα knockdown caused resistance of morphological changes in response to T3, but some other effects of T3, eg, those on feeding behavior, appeared to be less affected, suggesting that the requirement for the levels of TRα is tissue dependent and/or that TRβ and TRα may be redundant in some tissues.

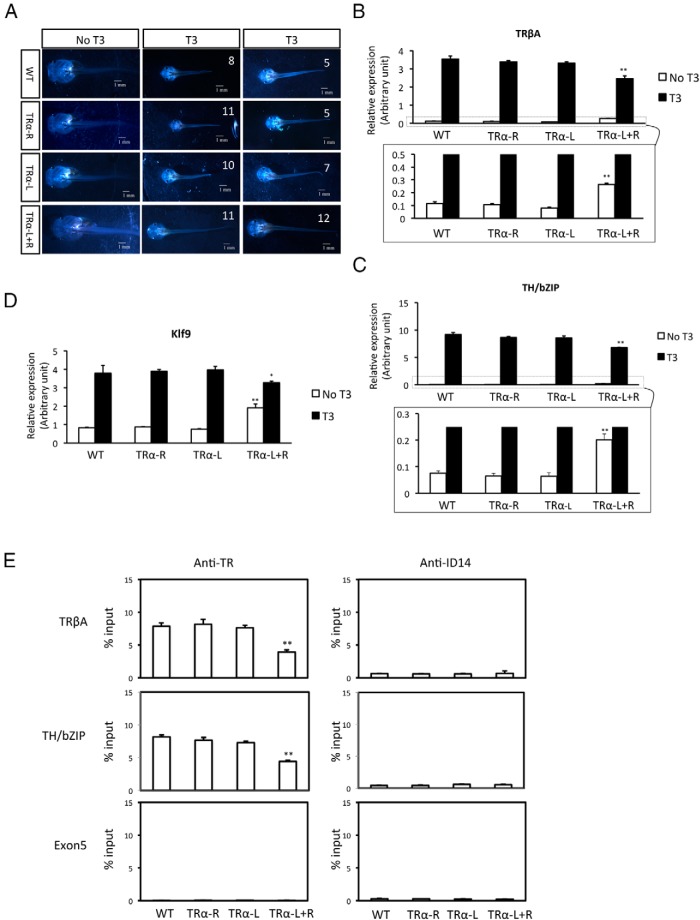

Figure 2.

TRα knockdown tadpoles resist T3 treatment. A, The TRα TALEN–injected tadpoles resist T3 induction. WT, no TALEN mRNA injection; TRα-R, TRα TALEN-R and control-L mRNAs injected; TRα-L, TRα TALEN-L arm and control-R mRNAs injected; TRα-L+R, TRα TALEN-L and -R mRNAs injected. There were 13 tadpoles in the WT group, 16 tadpoles in the TRα-R group, 17 tadpoles in the TRα-L group, and 23 tadpoles in the TRα-L+R group. Seven days after fertilization, the tadpoles (stage 48) were treated with 10 nM T3 for 5 days at 25°C and photographed. The animals in each group (WT, TRα-L, TRα-R, or TRα-L+R) were divided into 2 categories based on similarity in morphology after treatment. One representative photograph for each category is shown with the number of animals in the category. Note that in the absence of T3 treatment, tadpoles in different groups were similar. T3 induced morphological changes in the WT and control TALEN groups (top 3 rows), whereas tadpoles injected with both TRα TALEN arms had few morphological changes. B–D, T3-induction of target gene expression is reduced in TRα TALEN–injected tadpoles. Tadpoles were treated with 10 nM T3 for 18 hours. Total RNA was isolated and subjected to RT-PCR analysis for the expression of 3 known direct T3 target genes: TRβ (B), TH/bZIP (C), and klf9 (D). The boxed regions in the upper panels of B and C were enlarged and are shown in the lower panel to reveal the derepression caused by the knockdown. Note that the expression levels of all 3 genes were higher in the TRα TALEN–injected tadpoles in the absence of T3 but lower in the presence of T3 than in the WT and control TALEN–injected groups, suggesting that both the repression by unliganded TR and activation by T3-bound TR were reduced when TRα was knocked down. E, TRα knockdown reduces TR binding to TREs in vivo. Seven-day-old tadpoles (stage 48) were treated with 10 nM T3 for 18 hours. Whole tadpoles were then homogenized and subjected to ChIP assay for binding of TR to the TREs in the TRβ and TH/bZIP genes. The exon 5 of the TRβ gene was analyzed as a negative control for specificity of the binding, and anti-ID14 antibody was used as a negative control for antibody specificity. **, P < .01; *, P < .05, significant differences between the TRα knockdown group and all 3 other groups.

To determine whether the phenotype was indeed due to reduced TR function, we analyzed the expression of 3 well-known TR target genes, TRβ (61) and transcription factors TH/bZIP (62) and klf9 (63). As shown in Figure 2, B to D, T3 treatment led to strong induction of all 3 genes in the wild-type animals and in the animals injected with only one TRα TALEN arm. However, when both TRα TALEN arms were expressed, the induction of all 3 genes by T3 was reduced. Interesting, we also observed a significant increase in the expression of the 3 genes in the absence of T3 in the tadpoles injected with both TRα TALEN arms than in the other groups (Figure 2m B–D), suggesting that TRα knockdown also resulted in the derepression of the genes in the absence of T3.

TR is known to function by binding to TREs in the target genes constitutively. To determine whether the reduced response to T3 was due to the lack of TR binding to the target genes, we carried out a ChIP assay for TR binding to the known TREs in the TRβ and TH/bZip genes (31, 49, 61, 62). As shown in Figure 2E, TR binding to the TREs was reduced when both TRα TALEN arms were expressed. In contrast, TR binding was not affected if only one of the TRα TALEN arms was expressed. Thus, TRα knockdown led to reduced functional TR in the tadpoles, resulting in reduced induction of T3 response genes and metamorphic transformation.

TRα knockdown accelerates premetamorphic development

As indicated above, TRα TALEN expression in embryos appeared not to affect embryogenesis. These animals developed similarly to wild-type animals up to the feeding stage (stages 45/46). Interestingly, the TRα knockdown tadpoles subsequently grew faster. As animals tended to develop asynchronously, we grouped animals into 3 size categories at 20 days of age (Figure 3A). Quantitative analysis revealed significantly more large animals and fewer smaller animals in the group injected with both TRα TALEN arms than in the other groups (Figure 3B), indicating that TRα knockdown led to faster tadpole growth. Because GH gene plays a critical role in vertebrate growth and GH gene is known to be regulated by T3 in mammals (64, 65), we analyzed the expression of 2 GH genes in the animals and found that both were up-regulated in TRα knockdown animals (Figure 3C), suggesting that unliganded TR repressed the genes in premetamorphic tadpoles and TRα knockdown led to their derepression, just like the other 3 T3 target genes shown in Figure 2.

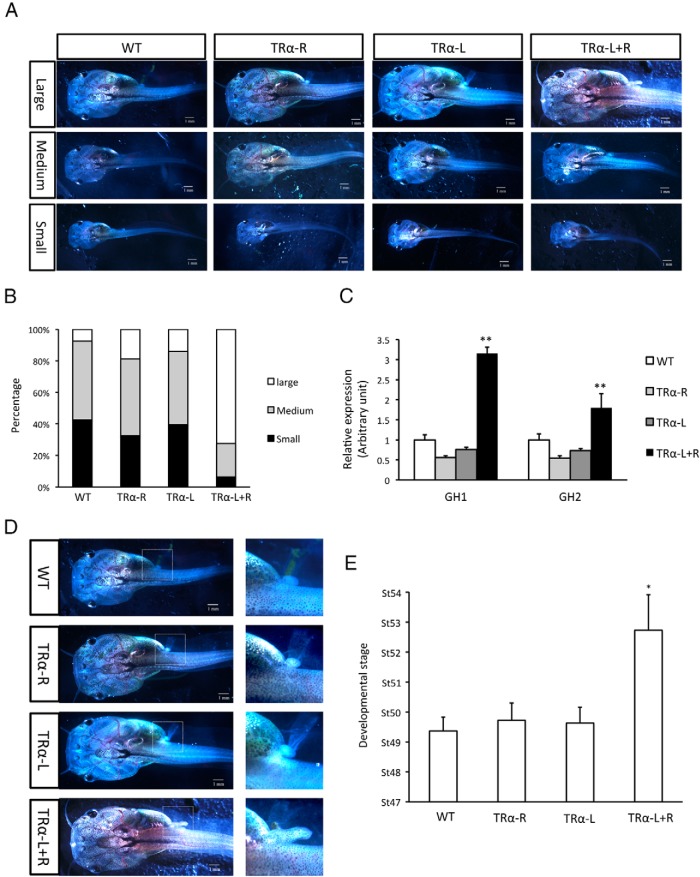

Figure 3.

TRα knockdown enhances tadpole growth and development during premetamorphosis. A, Tadpoles in different groups were classified into 3 categories (large size, medium size, and small size) at the age of 20 days postfertilization. There were 43 tadpoles in the WT group, 45 tadpoles in the TRα-R group, 46 tadpoles in the TRα-L group, and 49 tadpoles in the TRα-L+R group. One representative photo for each category is shown. See the legend to Figure 2 for additional information. B, Quantitative analysis of tadpole size for the animals shown in A. Note that the TRα knockdown group was overrepresented by large animals compared with the other groups. C, TRα knockdown increased GH gene expression. The tadpoles at 10 days postfertilization was used for RT-PCR analysis of the expression of 2 GH genes, GH1 and GH2. Note that both GH genes were expressed at significantly higher levels in the TRα-L+R group than in the other groups. **, P < .01, significant difference between the TRα knockdown group compared with all 3 other groups. D, TRα TALEN–injected tadpoles had more advanced development. Representative animals shown on the left were the same large animals shown in A. The area in the dashed box was magnified and is shown on the right (1 mm). Note the much more developed hindlimb for the TRα knockdown animal. E, TRα knockdown accelerates premetamorphic development. The individual animals in A and B were staged according to Ref. 51, and the average stage for each group is shown. Note that the TRα TALEN–injected group was on 3.5 stages more advanced in development than the other 3 groups, with some animals initiating metamorphosis (hindlimb morphogenesis around stage 54). *, P < .05, significant difference between the TRα knockdown group and all 3 other groups.

It has been proposed that unliganded TR controls metamorphic timing by repressing T3 target genes (19, 45, 46). The derepression of the TR target genes prompted us to analyze the morphology of the animals upon TRα knockdown. When animals of similar size in different TALEN mRNA–injected groups were analyzed, we noticed that the animals with both TRα TALEN arms injected were more advanced in development, and some animals had initiated metamorphosis, ie, reaching stage 54 (Figure 3D), whereas the control groups were several stages behind. Quantitative analysis showed that at 20 days of age, the wild-type animals as well as the animals injected with only 1 TRα TALEN arm plus a control arm were at an average stage of 49.5. In contrast, the animals injected with both TRα TALEN arms reached an average stage of 53, just before the onset of metamorphosis (Figure 3E). Thus, the removal of unliganded TR altered the timing of the initiation of natural metamorphosis, probably because of to the derepression of the T3 target genes important in metamorphosis (Figure 2).

TRα knockdown inhibits natural metamorphosis

The data above indicated that unliganded TRα is important for ensuring proper premetamorphic animal growth and also for responding to exogenous T3 to initiate induced metamorphosis. To determine the effect of TRα knockdown on natural metamorphosis, we selected tadpoles at around stage 54 based on limb morphology (51). Among these tadpoles, the TRα knockdown animals were much smaller that the wild-type or control TALEN–injected animals (Figure 4, A and B). Because the TRα knockdown animals grew faster, this finding suggests that TRα knockdown had an even bigger effect on animal development than on growth. When the animals around stage 54 were reared under identical conditions and observed until stage 58, the early metamorphic climax, we found that it took a similar number of days for the wild-type and control TALEN–injected animals to reach stage 58, with a mean of 19.2 days or less (Figure 4C). In contrast, the animals injected with both TRα TALEN arms took much longer, averaging about 30 days, more than 10 days longer (Figure 4C). Thus, the levels of TR dictate the rate of metamorphic progression.

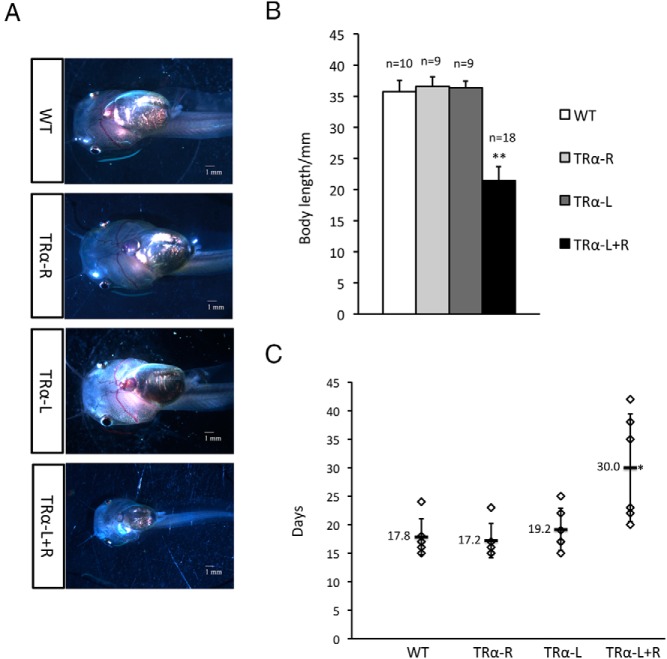

Figure 4.

TRα TALEN–injected tadpoles have a reduced rate of metamorphic progression. A, Representative photos of stage 54 (the onset of metamorphosis) tadpoles. Tadpoles were staged based on hindlimb morphology as described previously (51). Note that the tadpoles were at different ages. At stage 54, TRα TALEN–injected tadpoles were smaller than the WT and control TALEN–injected animals. This occurred because of the accelerated development caused by TRα knockdown (Figure 3), causing the animals to reach stage 54 at a much younger age and with a smaller size. B, Size of the tadpoles at stage 54. The body length of the animals at stage 54 for different groups in A are shown. n indicates the number of tadpoles for each group. Tadpole body length was measured from jaw to tail tips. *, P < .05, significant difference between the TRα knockdown group and all 3 other groups. C, TRα TALEN–injected tadpoles take longer to develop from stage 54 to stage 58, the early metamorphic climax. Six tadpoles around stage 54 in each group (the TRα knockdown tadpoles were at stage 54, whereas the animals in the other groups were around stage 50–54 because these other groups developed slower, and, thus, we chose the largest, most advanced for the experiments) were reared identically, and the time for each animal to reach stage 58 was measured based on animal morphology and is shown in the figure. Note that on average, the TRα TALEN–injected tadpoles took about 9 days longer to reach stage 58 than the animals in the other groups (the actually delay might be even longer if the animals in the non-TRα knockdown groups were all at stage 54 at the onset of the experiment). *, P < .05, significant difference between the TRα knockdown group and all 3 other groups.

Discussion

Ever since the demonstration that TRs can bind to TREs in chromatin constitutively but regulate gene expression in an opposite fashion depending on the presence or absence of T3, it has been assumed that both liganded and unliganded TRs have physiological functions in vivo. The presence of TR expression before the synthesis of endogenous T3 during vertebrate development argues for a role of unliganded TR during development, but direct evidence to support this has been lacking. The more severe phenotype caused by T3 deficiency on mouse development than by TR knockout (23–25) indicates that the continued presence of unliganded TRs during development is detrimental to mouse development, thus indicating a role for unliganded TR during early mouse embryogenesis when little or no T3 is present (20–22, 66). However, the potential contribution of maternal T3 to the mouse embryo complicates the interpretation and makes it difficult to ascertain a role for unliganded TR in mammals. Here, using amphibian development as a model, we provide the first direct evidence to show at the organismal level that unliganded TR regulates premetamorphic tadpole growth and the timing of metamorphosis and that the levels of TR regulate the rate of metamorphosis.

Frog development offers a valuable opportunity for studying the role of both ligand-bound and unliganded TR during vertebrate development because of the biphasic nature of its development. Its embryogenesis leads to the formation of a free-living tadpole in the absence of any maternal help, and the tadpole grows for a period of time before metamorphosis is triggered by the synthesis of endogenous T3. Thus, TRs are unliganded during premetamorphosis in tadpoles. (It should be pointed out that very low levels of T3 do exist during embryogenesis [59] and that unliganded TR also appears to be important for embryonic eye development [58].) Molecular studies have shown that TR functions by recruiting corepressors and coactivators to the target genes in the absence and presence of T3, respectively. Based on these and other studies, we have proposed a dual function model for TR during frog development (45, 46). That is, in premetamorphic tadpoles, unliganded TR recruits corepressors to repress TR target genes to prevent premature metamorphosis, whereas when T3 becomes available, TR recruits coactivators to activate target gene transcription and initiate metamorphosis.

Earlier studies have provided strong evidence supporting this dual function model. First, molecular and transgenic studies have suggested that TR is both necessary and sufficient for metamorphosis (29, 32–38, 41). Second, TR binds constitutively to endogenous target genes and recruits corepressors and coactivators in premetamorphic and metamorphosing tadpoles, respectively (11, 14, 67–75). Third, transgenic studies have shown that coactivator recruitment is essential for metamorphosis, whereas corepressor recruitment is critical for TR to control the initiation of metamorphosis (19, 70, 73, 74, 76). Of particular interest is a transgenic study involving a dominant-negative form of the corepressor N-CoR, which shows that disrupting the binding of a functional corepressor complex to unliganded TR leads to derepression of T3 target genes and precocious development of premetamorphic tadpoles, with the transgenic tadpoles initiating (reaching stage 54) earlier than the sibling wild-type animals. This supports a role of unliganded TR in recruiting corepressors to control target gene expression and metamorphic timing. A caveat of this study is, however, that the mutant N-CoR can affect the function of other nuclear hormone receptors and probably other transcription factors as well.

Here, making use of the recent development in TALEN technology to mutagenize endogenous genes in amphibians (52, 55), we have shown that TRα can be efficiently mutated upon overexpressing TRα TALEN mRNAs in fertilized eggs, with a mutation rate of more than 90%. (The actual rate might be even higher because our PCR screening method might miss some of the mutations, eg, when mutations occurred downstream of the primer f1 or point insertion/deletion/mutation near the 5′-end of the primer f1, consequently having little or no effect on the PCR with the f1 primer [Figure 1C].) This result makes it possible to study the role of endogenous TRα in the TALEN-injected animals. Importantly, our analyses of the TRα knockdown tadpoles not only provided direct in vivo evidence for the dual function model for TR but also revealed a novel role of TRα in regulating the rate of premetamorphic tadpole growth.

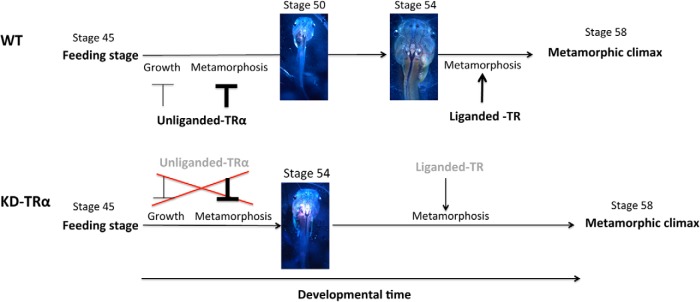

Our phenotypic analyses have shown that TRα knockdown leads to tadpole resistance to exogenous T3 treatment in terms of both the activation of endogenous T3 response genes and T3-induced metamorphic transformations. Mechanistically, we have shown that TRα knockdown results in the reduced occupancy of TRs at the target genes. Furthermore, TRα knockdown tadpoles take a much longer time to advance from stage 54, the onset of metamorphosis, to stage 58 (Figure 5), the onset of metamorphic climax, indicating that the levels of TRs regulate the rate of the progression of metamorphosis. Thus, our studies here provide direct evidence to support a critical role of endogenous TR in mediating the causative effect of T3 on metamorphosis, as first suggested by molecular and transgenic studies.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagrams showing the effect of TRα knockdown (KD-TRα) on Xenopus development. TRα is highly expressed by tadpole feeding stage. The unliganded TR in wild-type tadpoles has a larger effect (darker T-bar) in repressing precocious metamorphosis but a smaller effect (lighter T-bar) in inhibiting growth; this allows coordinated growth and development of the animals before the onset of metamorphosis (stage 54). In TRα knockdown tadpoles, the unliganded TR level is reduced (shown in lighter letters). This reduces the effects of TRα on both growth and development, leading to faster growth and even faster development. The result is larger but developmentally more advanced tadpoles than the wild type at the same developmental time point (eg, stage 50 for wild-type and stage 54 for KD-TRα tadpoles as shown in the figure). The wild-type animal takes longer to reach metamorphosis (stage 54) and has a larger size because of the longer growth period that more than compensates for the slower growth compared with that of the knockdown animals. Once metamorphosis begins (stage 54), the lower levels of TRα in the KD-TRα tadpoles (lighter letters) lengthen the time needed to reach metamorphic climax (stage 58).

The dual function model for TR argues for a critical role of unliganded TR in regulating the timing of metamorphosis. We have shown that TRα knockdown leads to precocious development, enabling premetamorphic tadpoles to reach stage 54, the onset of metamorphosis, much earlier than the wild-type siblings (Figure 5). Furthermore, our gene expression studies showed that all 3 direct target genes of T3 we analyzed (TRβ, TH/bZIP, and klf9) were derepressed upon TRα knockdown in premetamorphic tadpoles. These findings indicate that the expression of TRα in premetamorphic tadpoles functions to repress T3 target genes and control the timing of metamorphosis, supporting the role of unliganded TR in the dual function model.

Interestingly, although TRα knockdown did not appear to affect embryogenesis because there was no apparent difference between wild-type and TRα knockdown tadpoles at the feeding stage (stage 45), the TRα knockdown tadpoles subsequently grew faster, leading to larger animals when premetamorphic animals (before stage 54) of the same ages were compared (Figure 5). Although the exact mechanism for this growth acceleration is unclear, our data suggest that the up-regulation of the GH expression in TRα knockdown tadpoles is responsible for or contributes. It is well known that the GH gene in mammals is regulated by T3 directly at the transcription level (64, 65), and it is tempting to speculate that the frog GH genes are similarly regulated by T3 and thus TRα knockdown would lead to the observed derepression of the genes caused by unliganded TR in premetamorphic tadpoles. In the future, it will be interesting to determine through in vitro and in vivo promoter studies whether this is indeed the mechanism.

When animals at the same stages, ie, stage 54 (the onset of metamorphosis when endogenous plasma T3 becomes detectable) were compared, TRα knockdown tadpoles were actually smaller than the wild-type siblings (Figure 4), despite the faster growth of these animals. Thus, the acceleration of tadpole growth caused by TRα knockdown appeared to be uncoupled from the acceleration of tadpole development due to TRα knockdown. This novel finding suggests that the rate of growth and the rate of development of premetamorphic tadpoles probably involve different regulation pathways. Whereas the exact mechanisms controlling the growth rate and development remain to be determined, our results indicate that unliganded TRα affects both. Unliganded TRα appears to have a greater effect on the rate of animal development toward metamorphosis but a smaller effect on the rate of animal growth (Figure 5). Therefore, when TR is knocked down, the acceleration in growth (as judged based on size) would be smaller than the acceleration in development (as judged on the basis of the developmental stages of the animals). Thus, when animals are compared at the same developmental time (age), the knockdown animals will be bigger. However, when compared at the same developmental stage at the onset of metamorphosis, ie, after all animals are allowed to reach stage 54 regardless of the time needed, the knockdown animals are smaller. The reason is that the knockdown animals develop very fast and have a much shorter time to grow before reaching stage 54 than the wild-type animals. The slower growth of wild-type animals is more than compensated for by the much longer growth time needed to reach stage 54. Consequently, TRα knockdown animals, although faster in growth, are nonetheless smaller at the onset of metamorphosis than the wild-type siblings (Figure 5, compare animals at stage 54). Our findings suggest that the up-regulation of GH genes due to TRα knockdown may be one mechanism for the faster growth. Clearly, additional studies, such as identifying and functionally characterizing other genes regulated by TRα, are needed to determine why and how the rate of growth and the rate of development are differentially affected by the TRα knockdown.

Whereas our studies here are the first to provide direct evidence for a critical role of unliganded TR in vertebrate development, earlier studies suggested that unliganded TR is also probably involved in mouse embryogenesis. As indicated above, the distinct phenotypes caused by T3 deficiency and TR knockout indicate a role for unliganded TR for early mouse development when plasma T3 levels are low. Furthermore, several studies suggest a role of unliganded TR in the development of at least some mouse organs. For example, in mouse embryos where T3 levels are low, TRα knockout increases the heart rate as well as the expression of several T3 response genes in the heart (77). In postnatal mice when T3 levels are high, the expression of these same T3 response genes and the heart rate are lower in the knockout mice than in the wild-type siblings, suggesting that TRα represses the target genes and keeps the heart rate low in the unliganded state in the embryos and does the opposite when T3 levels are high after birth (77). In addition, TRβ deletion leads to hearing loss in both mouse and human and causes major defects in the photoreceptor cells in mouse, but mutations in TRβ that result in the formation of dominant-negative forms of TRβ have only mild effects on the auditory and visual systems (78–83), suggesting that unliganded TRβ is important for the development of the auditory and visual systems in mouse and human. Consistently, deletion of the gene encoding the T3-inactivating enzyme, type 3 deiodinase, also causes auditory defects (84). Finally, unliganded TR is known to recruit the corepressors N-CoR and SMRT, which in turn form complexes with histone deacetylases. In vivo studies have shown that mutations in the endogenous N-CoR and SMRT genes in mice that disrupt the corepressor-TR interaction or deacetylase activation lead to derepression of T3-inducible genes, supporting a role of corepressor recruitment by unliganded TR in gene regulation in vivo (85–87). Thus, mammalian development probably also utilizes unliganded TR, especially during early embryogenesis when T3 levels are low, to coordinate organ development and maturation, similar to premetamorphic tadpole development.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the intramural Research Program of The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

For News & Views see page 409; for related article see page 735

- ChIP

- chromatin immunoprecipitation

- hGC

- human chorionic gonadotropin

- MMR

- Marc's modified Ringers solution

- TALEN

- transcriptional activator like effector nuclease

- TR

- T3 receptor

- TRE

- T3 response element.

References

- 1. Lazar MA. Thyroid hormone receptors: multiple forms, multiple possibilities. Endocr Rev. 1993;14:184–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Evans RM. The steroid and thyroid hormone receptor superfamily. Science. 1988;240:889–895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yen PM. Physiological and molecular basis of thyroid hormone action. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:1097–1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tsai MJ, O'Malley BW. Molecular mechanisms of action of steroid/thyroid receptor superfamily members. Annu Rev Biochem. 1994;63:451–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Buchholz DR, Paul BD, Fu L, Shi YB. Molecular and developmental analyses of thyroid hormone receptor function in Xenopus laevis, the African clawed frog. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2006;145:1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shi YB, Matsuura K, Fujimoto K, Wen L, Fu L. Thyroid hormone receptor actions on transcription in amphibia: the roles of histone modification and chromatin disruption. Cell Biosci. 2012;2:42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hsia SC, Wang H, Shi YB. Involvement of chromatin and histone acetylation in the regulation of HIV-LTR by thyroid hormone receptor. Cell Res. 2001;11:8–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wong J, Shi YB. Coordinated regulation of and transcriptional activation by Xenopus thyroid hormone and retinoid X receptors. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:18479–18483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wong J, Shi YB, Wolffe AP. A role for nucleosome assembly in both silencing and activation of the Xenopus TR beta A gene by the thyroid hormone receptor. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2696–2711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Burke LJ, Baniahmad A. Co-repressors 2000. FASEB J. 2000;14:1876–1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jones PL, Shi YB. N-CoR-HDAC corepressor complexes: roles in transcriptional regulation by nuclear hormone receptors. Curr Top Microbiol. 2003;274:237–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG. The coregulator exchange in transcriptional functions of nuclear receptors. Genes Dev. 2000;14:121–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhang J, Lazar MA. The mechanism of action of thyroid hormones. Annu Rev Physiol. 2000;62:439–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jones PL, Sachs LM, Rouse N, Wade PA, Shi YB. Multiple N-CoR complexes contain distinct histone deacetylases. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:8807–8811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McKenna NJ, O'Malley BW. Nuclear receptors, coregulators, ligands, and selective receptor modulators: making sense of the patchwork quilt. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2001;949:3–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rachez C, Freedman LP. Mediator complexes and transcription. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2001;13:274–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tata JR. Gene expression during metamorphosis: an ideal model for post-embryonic development. Bioessays. 1993;15:239–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shi YB. Unliganded thyroid hormone receptor regulates metamorphic timing via the recruitment of histone deacetylase complexes. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2013;105:275–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sato Y, Buchholz DR, Paul BD, Shi YB. A role of unliganded thyroid hormone receptor in postembryonic development in Xenopus laevis. Mech Dev. 2007;124:476–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Morreale de Escobar G, Calvo R, Escobar del Rey F, Obregón MJ. Thyroid hormones in tissues from fetal and adult rats. Endocrinology. 1994;134:2410–2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hadj-Sahraoui N, Seugnet I, Ghorbel MT, Demeneix B. Hypothyroidism prolongs mitotic activity in the post-natal mouse brain. Neurosci Lett. 2000;280:79–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nagasawa T, Suzuki S, Takeda T, DeGroot LJ. Thyroid hormone receptor β 1 expression in developing mouse limbs and face. Endocrinology. 1997;138:1276–1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mansouri A, Chowdhury K, Gruss P. Follicular cells of the thyroid gland require Pax8 gene function. Nat Genet. 1998;19:87–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Flamant F, Poguet AL, Plateroti M, et al. Congenital hypothyroid Pax8(−/−) mutant mice can be rescued by inactivating the TRα gene. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16:24–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Flamant F, Samarut J. Thyroid hormone receptors: lessons from knockout and knock-in mutant mice. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2003;14:85–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shi Y-B. Amphibian Metamorphosis: From Morphology to Molecular Biology. New York, NY: John Wiley; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Brown DD, Cai L. Amphibian metamorphosis. Dev Biol. 2007;306:20–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Denver RJ. Neuroendocrinology of amphibian metamorphosis. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2013;103:195–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Puzianowska-Kuznicka M, Damjanovski S, Shi YB. Both thyroid hormone and 9-cis retinoic acid receptors are required to efficiently mediate the effects of thyroid hormone on embryonic development and specific gene regulation in Xenopus laevis. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:4738–4749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sachs LM, Shi YB. Targeted chromatin binding and histone acetylation in vivo by thyroid hormone receptor during amphibian development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:13138–13143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Buchholz DR, Paul BD, Shi YB. Gene-specific changes in promoter occupancy by thyroid hormone receptor during frog metamorphosis. Implications for developmental gene regulation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:41222–41228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nakajima K, Yaoita Y. Dual mechanisms governing muscle cell death in tadpole tail during amphibian metamorphosis. Dev Dyn. 2003;227:246–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schreiber AM, Brown DD. Tadpole skin dies autonomously in response to thyroid hormone at metamorphosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:1769–1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Das B, Schreiber AM, Huang H, Brown DD. Multiple thyroid hormone-induced muscle growth and death programs during metamorphosis in Xenopus laevis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:12230–12235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Schreiber AM, Das B, Huang H, Marsh-Armstrong N, Brown DD. Diverse developmental programs of Xenopus laevis metamorphosis are inhibited by a dominant negative thyroid hormone receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:10739–10744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Buchholz DR, Hsia SC, Fu L, Shi YB. A dominant-negative thyroid hormone receptor blocks amphibian metamorphosis by retaining corepressors at target genes. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:6750–6758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Buchholz DR, Tomita A, Fu L, Paul BD, Shi YB. Transgenic analysis reveals that thyroid hormone receptor is sufficient to mediate the thyroid hormone signal in frog metamorphosis. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:9026–9037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hasebe T, Buchholz DR, Shi YB, Ishizuya-Oka A. Epithelial-connective tissue interactions induced by thyroid hormone receptor are essential for adult stem cell development in the Xenopus laevis intestine. Stem Cells. 2011;29:154–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hasebe T, Fu L, Miller TC, Zhang Y, Shi YB, Ishizuya-Oka A Thyroid hormone-induced cell-cell interactions are required for the development of adult intestinal stem cells. Cell Biosci. 2013;3:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Shi YB, Hasebe T, Fu L, Fujimoto K, Ishizuya-Oka A The development of the adult intestinal stem cells: insights from studies on thyroid hormone-dependent amphibian metamorphosis. Cell Biosci. 2011;1:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Grimaldi AG, Buisine N, Bilesimo P, Sachs LM. High-throughput sequencing will metamorphose the analysis of thyroid hormone receptor function during amphibian development. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2013;103:277–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Denver RJ, Hu F, Scanlan TS, Furlow JD. Thyroid hormone receptor subtype specificity for hormone-dependent neurogenesis in Xenopus laevis. Dev Biol. 2009;326:155–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yaoita Y, Brown DD. A correlation of thyroid hormone receptor gene expression with amphibian metamorphosis. Genes Dev. 1990;4:1917–1924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wang X, Matsuda H, Shi YB. Developmental regulation and function of thyroid hormone receptors and 9-cis retinoic acid receptors during Xenopus tropicalis metamorphosis. Endocrinology. 2008;149:5610–5618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Shi YB, Wong J, Puzianowska-Kuznicka M, Stolow MA. Tadpole competence and tissue-specific temporal regulation of amphibian metamorphosis: roles of thyroid hormone and its receptors. BioEssays. 1996;18:391–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sachs LM, Damjanovski S, Jones PL, et al. Dual functions of thyroid hormone receptors during Xenopus development. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 2000;126:199–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bilesimo P, Jolivet P, Alfama G, et al. Specific histone lysine 4 methylation patterns define TR-binding capacity and differentiate direct T3 responses. Mol Endocrinol. 2011;25:225–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Amaya E, Offield MF, Grainger RM. Frog genetics: Xenopus tropicalis jumps into the future. Trends Genet. 1998;14:253–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Matsuura K, Fujimoto K, Fu L, Shi YB. Liganded thyroid hormone receptor induces nucleosome removal and histone modifications to activate transcription during larval intestinal cell death and adult stem cell development. Endocrinology. 2012;153:961–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Matsuura K, Fujimoto K, Das B, Fu L, Lu CD, Shi YB. Histone H3K79 methyltransferase Dot1L is directly activated by thyroid hormone receptor during Xenopus metamorphosis. Cell Biosci. 2012;2:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Nieuwkoop PD, Faber J. Normal table of Xenopus laevis, 1st ed Amsterdam, The Netherlands: North Holland Publishing; 1956. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lei Y, Guo X, Deng Y, Chen Y, Zhao H. Generation of gene disruptions by transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs) in Xenopus tropicalis embryos. Cell Biosci. 2013;3:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Cermak T, Doyle EL, Christian M, et al. Efficient design and assembly of custom TALEN and other TAL effector-based constructs for DNA targeting. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:e82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Fu L, Buchholz D, Shi YB. Novel double promoter approach for identification of transgenic animals: A tool for in vivo analysis of gene function and development of gene-based therapies. Mol Reprod Dev. 2002;62:470–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lei Y, Guo X, Liu Y, et al. Efficient targeted gene disruption in Xenopus embryos using engineered transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:17484–17489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Buchholz DR, Ishizuya-Oka A, Shi YB. Spatial and temporal expression pattern of a novel gene in the frog Xenopus laevis: correlations with adult intestinal epithelial differentiation during metamorphosis. Gene Expr Patterns. 2004;4:321–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Eliceiri BP, Brown DD. Quantitation of endogenous thyroid hormone receptors α and β during embryogenesis and metamorphosis in Xenopus laevis. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:24459–24465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Havis E, Le Mevel S, Dubois GM, Shi D-L, Scanlan TS, Demeneix BA, Sachs LM. Unliganded thyroid hormone receptor is essential for Xenopus laevis eye development. EMBO J. 2006;25:4943–4951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Morvan Dubois G, Sebillot A, Kuiper GG, Verhoelst CH, Darras VM, Visser TJ, Demeneix BA. Deiodinase activity is present in Xenopus laevis during early embryogenesis. Endocrinology. 2006;147:4941–4949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Tata JR. Early metamorphic competence of Xenopus larvae. Dev Biol. 1968;18:415–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ranjan M, Wong J, Shi YB. Transcriptional repression of Xenopus TR β gene is mediated by a thyroid hormone response element located near the start site. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:24699–24705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Furlow JD, Brown DD. In vitro and in vivo analysis of the regulation of a transcription factor gene by thyroid hormone during Xenopus laevis metamorphosis. Mol Endocrinol. 1999;13:2076–2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Furlow JD, Kanamori A. The transcription factor basic transcription element-binding protein 1 is a direct thyroid hormone response gene in the frog Xenopus laevis. Endocrinology. 2002;143:3295–3305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Santos A, Perez-Castillo A, Wong NC, Oppenheimer JH. Labile proteins are necessary for T3 induction of growth hormone mRNA in normal rat pituitary and rat pituitary tumor cells. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:16880–16884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Kanamori A, Brown DD. The regulation of thyroid hormone receptor beta genes by thyroid hormone in Xenopus laevis. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:739–745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Howdeshell KL. A model of the development of the brain as a construct of the thyroid system. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110:337–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Tomita A, Buchholz DR, Shi YB. Recruitment of N-CoR/SMRT-TBLR1 corepressor complex by unliganded thyroid hormone receptor for gene repression during frog development. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:3337–3346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Sachs LM, Jones PL, Havis E, Rouse N, Demeneix BA, Shi YB. Nuclear receptor corepressor recruitment by unliganded thyroid hormone receptor in gene repression during Xenopus laevis development. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:8527–8538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Matsuda H, Paul BD, Choi CY, Shi YB. Contrasting effects of two alternative splicing forms of coactivator-associated arginine methyltransferase 1 on thyroid hormone receptor-mediated transcription in Xenopus laevis. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21:1082–1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Matsuda H, Paul BD, Choi CY, Hasebe T, Shi YB. Novel functions of protein arginine methyltransferase 1 in thyroid hormone receptor-mediated transcription and in the regulation of metamorphic rate in Xenopus laevis. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:745–757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Paul BD, Shi YB. Distinct expression profiles of transcriptional coactivators for thyroid hormone receptors during Xenopus laevis metamorphosis. Cell Res. 2003;13:459–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Paul BD, Buchholz DR, Fu L, Shi YB. Tissue- and gene-specific recruitment of steroid receptor coactivator-3 by thyroid hormone receptor during development. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:27165–27172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Paul BD, Fu L, Buchholz DR, Shi YB. Coactivator recruitment is essential for liganded thyroid hormone receptor to initiate amphibian metamorphosis. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:5712–5724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Paul BD, Buchholz DR, Fu L, Shi YB. SRC-p300 coactivator complex is required for thyroid hormone-induced amphibian metamorphosis. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:7472–7481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Havis E, Sachs LM, Demeneix BA. Metamorphic T3-response genes have specific co-regulator requirements. EMBO Rep. 2003;4:883–888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Matsuda H, Shi YB. An essential and evolutionarily conserved role of protein arginine methyltransferase 1 for adult intestinal stem cells during postembryonic development. Stem Cells. 2010;28:2073–2083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Mai W, Janier MF, Allioli N, et al. Thyroid hormone receptor alpha is a molecular switch of cardiac function between fetal and postnatal life. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:10332–10337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Griffith AJ, Szymko YM, Kaneshige M, et al. Knock-in mouse model for resistance to thyroid hormone (RTH): an RTH mutation in the thyroid hormone receptor beta gene disrupts cochlear morphogenesis. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2002;3:279–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Brucker-Davis F, Skarulis MC, Pikus A, Ishizawar D, Mastroianni MA, Koby M, Weintraub BD. Prevalence and mechanisms of hearing loss in patients with resistance to thyroid hormone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:2768–2772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Refetoff S, DeWind LT, DeGroot LJ. Familial syndrome combining deaf-mutism, stuppled epiphyses, goiter and abnormally high PBI: possible target organ refractoriness to thyroid hormone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1967;27:279–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Ng L, Hurley JB, Dierks B, et al. A thyroid hormone receptor that is required for the development of green cone photoreceptors. Nat Genet. 2001;27:94–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Jones I, Srinivas M, Ng L, Forrest D. The thyroid hormone receptor beta gene: structure and functions in the brain and sensory systems. Thyroid. 2003;13:1057–1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Forrest D, Erway LC, Ng L, Altschuler R, Curran T. Thyroid hormone receptor β is essential for development of auditory function. Nat Genet. 1996;13:354–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Ng L, Hernandez A, He W, et al. A protective role for type 3 deiodinase, a thyroid hormone-inactivating enzyme, in cochlear development and auditory function. Endocrinology. 2009;150:1952–1960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Astapova I, Lee LJ, Morales C, Tauber S, Bilban M, Hollenberg AN. The nuclear corepressor, NCoR, regulates thyroid hormone action in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:19544–19549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. You SH, Liao X, Weiss RE, Lazar MA. The interaction between nuclear receptor corepressor and histone deacetylase 3 regulates both positive and negative thyroid hormone action in vivo. Mol Endocrinol. 2010;24:1359–1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Pei L, Leblanc M, Barish G, et al. Thyroid hormone receptor repression is linked to type I pneumocyte-associated respiratory distress syndrome. Nat Med. 2011;17:1466–1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]