Abstract

It has been suggested that depression is a polygenic trait, arising from the influences of multiple loci with small individual effects. The aim of this study is to generate a polygenic risk score (PRS) to examine the association between genetic variation and depressive symptoms. Our analytic sample included N=10,091 participants ages 50+ from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS). Depressive symptoms were measured by CESD scores assessed on up to nine occasions across 18 years. We conducted a genome-wide association analysis for a discovery set (n=7,000) and used the top 11 single nucleotide polymorphisms, all with P<10−05 to generate a weighted PRS for our replication sample (n=3,091). Results showed the PRS was significantly associated with mean CESD score in the replication sample (β=.08, P=.002). The R2-change for the inclusion of the PRS was .003. Using a multinomial logistic regression model we also examined the association between genetic risk and chronicity of high (4+) CESD scores. We found that a one standard deviation increase in PRS was associated with a 36% increase in the odds of having chronically high CESD scores relative to never having had high CESD scores. Our findings are consistent with depression being a polygenic trait and suggest that the cumulative influence of multiple variants increase an individual’s susceptibility for chronically experiencing high levels of depressive symptoms.

Introduction

Depression has substantial public health implications. It has been shown to exacerbate disease progression, disability, and cognitive decline, as well as increase the risk of mortality (Reddy, 2010; Ferrari et al., 2013). It is also one of the most common psychiatric illnesses. Among the older U.S. population, the prevalence of a high level of depressive symptoms is 14.6% (Zivin et al. 2010) while the prevalence of major depressive disorder is 6.7% (Kessler et al, 2003). It is also estimated that just over 16% of the population will experience a major depressive episode at least once in their lifetime.

While negative events in a person’s life often increase the risk of experiencing symptoms of depression, genetic differences also shape susceptibility. Studies dating back to the early 20th century have provided evidence that depression runs in families (reviewed in Tsuang & Faraone, 1990). Twin studies of older adults suggest that the number of depressive symptoms is approximately 20–30% heritable (McGue & Christensen, 2003; Jansson et al., 2004) and similar estimates have been found for MDD based on twin and genotype data (Sullivan et al., 2000; Lubke et al., 2012). Identifying the biological pathways and genes associated with depressive symptoms has the potential to facilitate our understanding of the pathophysiology of depression, and in turn lead to improved treatment and prevention (Flint & Kendler, 2014).

Nevertheless, there has been little success to-date in uncovering susceptibility loci for depressive phenotypes. Even a mega-analysis on nearly 19,000 subjects, conducted by the Major Depressive Disorder Working Group of the Psychiatric Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS) Consortium (Ripke, 2013) did not identify any SNPs that met genome-wide significance. While the authors indicate the need for larger sample sizes, another way to identify causal variants may be to consider the cumulative associations of multiple SNPs simultaneously (Wray et al., 2007). As with other complex disorders that are common in the population, depression appears to be a multifactorial, polygenic trait, influenced by multiple environmental factors and multiple genetic loci whose individual effects are too small to confirm with current sample sizes (Collins & Sullivan, 2013).

One way to examine the aggregate influence of multiple genetic markers is by generating a Polygenic Risks Score (PRS) based on results from a GWAS. A PRS can be thought of as a measure of ‘genetic burden’ associated with a phenotype (Wray et al., 2008). One of the earliest examples incorporating these scores with GWAS examined the genetic underpinnings of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (Purcell et al. 2009), and since then use of PRS has become increasingly popular, facilitating genetic discoveries for complex traits. PRSs are generated by running a GWAS on a discovery sample, selecting SNPs on the basis of their association with the phenotype, and creating a sum of their phenotype-associated alleles (often weighted by the SNP-specific coefficients from the GWAS), that can be evaluated in a separate replication sample (Dudbridge, 2013). PRSs are based on the idea that many variants with small individual effects will not meet genome-wide significance thresholds, yet collectively may have a strong effect (Wray et al., 2007; Wray et al., 2008).

In addition to considering the cumulative association across multiple SNPs, our ability to identify risk alleles is influenced by measurement of the phenotype. Typically, binary diagnostic categories have been used as the standard phenotype for depression GWAS. However, if depression-related pathophysiology is polygenic, one would expect to see a spectrum regarding the levels of depressive symptoms and thus a continuous symptoms measure may be more appropriate (Chang et al., 2014). Examining the chronicity of these traits may also facilitate genetic discovery. The number of depressive symptoms an individual reports may be strongly influenced by his/her environmental circumstances or recent life events. However, for individuals who are genetically predisposed to experience higher levels of depressive symptoms, these fluctuations may be less contextually dependent, and thus may remain more stable over time (Chang et al., 2014). For this reason we also examine the chronicity over time of high levels of depressive symptoms.

The goal of the current study is to use a nationally-representative longitudinal study of older U.S. adults to 1) conduct a GWAS on participant’s mean level of depressive symptoms over an eighteen year period, 2) use those findings to generate a PRS in a separate sub-sample of the same population, and 3) examine the association between the PRS and both the level and chronicity of depressive symptoms in the replication sample.

Methods

Sample and Study Design

Genetic data came from saliva samples collected during the 2006 and 2008 waves of the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), a nationally-representative longitudinal study of health and aging in the U.S, collected every two years since 1992. For our analysis we selected participants who self-reported their race as white/Caucasian, had available genetic data, and had at least three waves of data on depressive symptoms from any of the nine waves of the HRS between 1994 and 2010. This left us with an analytic sample of N=10,091. Non-whites were excluded to increases the ancestral homogeneity of our sample, while individuals with fewer than three CESD scores were excluded to ensure that we had sufficient observations to characterize participants’ depressive symptoms over time. Compared to the entire HRS sample of non-Hispanic whites, the analytic sample is more likely to include people over the age of 85 and people with less than a high-school degree. However, the samples do not differ in distributions of gender or U.S. region of residence.

The analytic sample was split into two random groups using a random number generator to create a discovery ample (n=7,000) and a replication sample (n=3,091). For our analysis, the discovery set was used to identify candidate SNPs associated with a person’s mean number of depressive symptoms from which to create a PRS; our replication set was used to test whether the PRS was associated with mean levels of depressive symptoms as well as chronicity of depressive symptoms. Because our GWAS was used to identify candidate SNPs for inclusion in our PRS—considering all those with P<.05—rather than identifying individual explanatory SNPs, we were more concerned with having sufficient power to identify significant association between our PRS and mean number of depressive symptoms in our replication sample. A power analysis showed we would need a replication sample of 3,000 to yield a power of around 0.8 for a PRS explaining 0.25% of the variance in mean number of depressive symptoms (R2=.0025), which is on par with R2 that have been reported for other complex traits (Dudbridge, 2013).

Depressive Symptoms Measure

CESD8 (the eight item Center for Epidemiologic Studies of Depression scale) was used to quantify participants’ number of depressive symptoms. This measure is a linear composite of participant’s binary, yes or no, responses to eight items, with possible values ranging from 0 to 8. For these items respondents were asked, whether over the past week they: 1) felt depressed, 2) felt like everything was an effort, 3) had restless sleep, 4) felt happy (reverse coded), 5) felt lonely, 6) enjoyed life (reverse coded), 7) felt sad, or 8) could not get going. For each participant, a mean CESD8 score was created using data across all waves (except from the 1992 wave which used a different measure) with non-missing data. We found strong (within-person) internal consistency in CESD scores across the nine waves (Cronbach’s alpha=0.89).

In addition to the mean CESD, we also examine a categorical variable that reflects the chronicity of high levels of depressive symptoms. Participants who had information on CESD for at least three waves were classified into five categories depending on whether they: 1) reported less than four depressive symptoms for all waves they were observed, 2) reported four or more depressive symptoms for fewer than one-half of the waves they were observed (but at least one), 3) reported four or more depressive symptoms for more than one-half, but less than all of the waves they were observed, 4) reported four or more depressive symptoms at every wave they were observed. The cut-off of four or more depressive symptoms was chosen to reflect a level of depressive symptoms that is clinically noteworthy but it does not reflect a diagnostic category (Steffick, 2000; Zivin et al. 2010).

Genome-Wide SNP Analysis

Genotyping was performed by the NIH Center for Inherited Disease Research (CIDR) using the Illumina Human Omni-2.5 Quad beadchip, with coverage of approximately 2.5 million single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). Initial Quality Control measures were performed by HRS to test CIDR technical filters, duplicates, missing call rates >=2%, Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium P-values <10-4 in European and African samples, sex differences in all allelic frequency >=0.2, and sex differences in heterozygosity >0.3. We were left with 2,201,371 SNPs for our GWAS. More information on QC checks is provided by HRS (HRS, 2012). Finally, in order to minimize the bias from rare SNPs that potentially generate inflated P-values, we set our minor allele frequency (MAF) cutoff at 0.05, which left us with a total of 1,271,442 SNPs for our analysis. Principal component analysis (PCA) was conducted by the HRS in accordance with the methods described by Patterson et al. (2006) in order to account for population structure. A scree plot generated by HRS showed that the 20 components produced by the PCA only accounted for a small fraction of the overall genetic variance (<4%) and that most of this was contained within the first two components (HRS, 2012). Because our analysis used data on whites only there was less of a need to use a large number of eigenvectors as controls. Nevertheless, we adjusted for the first four eigenvectors in all subsequent analyses.

Statistical Analysis

With our discovery sample, we conducted a quantitative trait based GWAS, using the mean number of depressive symptoms over three to nine waves as our dependent variable, and adjusting for sex and the first four eigenvectors. SNPs were then grouped based on empirical estimates of Linkage Disequilibrium (LD) using the clump command in PLINK (PLINK 1.9, Shaun Purcell, http://pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/purcell/plink/). This analysis reports index SNPs—denoted as the most significant SNP (from the GWAS results) for each group of correlated SNPs. For this procedure, we considered all SNPs with P-values<.05, and used a distance of 250kb and an R2 threshold of 0.50 to group SNPs.

Next, five PRS were constructed based on our GWAS results using various P-value cutoffs for inclusion criteria. The PRS was calculated as the sum of the risk alleles, weighted by their coefficients from our GWAS results (Dudbridge, 2013). For instance, this score assumes a dose response for each SNP, where persons who are homozygous for the risk allele are given a score of two, those who are heterozygous are given a score of 1, and those who are homozygous for the non-risk allele are given a score of 0. These scores are then multiplied by the coefficient for that SNP from the GWAS results and then summed across SNPs. PRS calculation were done using PLINK with the option ‘no mean imputation’ specified—missing alleles were not set as the most common allele based on the sample allele frequencies, but rather PRS only took into account those SNPs which were directly genotyped.

The associations between mean CESD and the five PRS were then evaluated using the discovery sample in order to select the appropriate PRS to evaluate in the validation sample. Ordinary least squares and Poisson regressions, adjusting for the eigenvectors, age, and sex were used to examine the association between PRS and CESD and to ensure that the distribution of CESD did not bias our results. Multinomial logistic regression adjusting for the four eigenvectors, age, and sex was used to examine the association between PRS and the likelihood of inclusion in the five depressive symptoms chronicity categories. Finally, spline graphs with 4 knots were generated to visualize the association between increases in PRS and increases in both level and chronicity of CESD. STATA (StataCorp. 2013. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP) was used to examine the association between PRS and CESD in the replication sample, while the GWAS and the calculation of the PRSs were run using PLINK (PLINK 1.9, Shaun Purcell, http://pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/purcell/plink/).

Results

Sample Characteristics

Our discovery and replication sets had equivalent characteristics, as shown in Table 1. Both samples were 65 years old on average (SD=10.3), and were approximately 59% female. Additionally, mean CESD was 1.28 (SD=1.4) for the discovery sample and 1.30 (1.4) for the replication sample. We also observed similar genetic ancestry between the two sub-samples, as signified by eigenvector scores. For both the discovery and replication samples, just over 57% of participants never reported four or more depressive symptoms, approximately 32% reported four or more symptoms less than half of the times observed, and about 9% reported four or more symptoms more than half the time. Additionally, 1.18% (n=81) participants in the discovery sample reported four or more depressive symptoms at every wave, while 1.8 (n=58) reported this in the replication sample.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics

| Variable | Full Sample (N=10,091) |

Discovery Set (N=7,000) |

Replication Set (N=3,091) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std. Dev. | Mean | Std. Dev. | Mean | Std. Dev. | ||

| Age | overall | 65.24 | 10.34 | 65.20 | 10.33 | 65.35 | 10.35 |

| between | 9.43 | 9.41 | 9.46 | ||||

| within | 5.12 | 5.12 | 5.10 | ||||

| CESD | overall | 1.26 | 1.82 | 1.26 | 1.83 | 1.26 | 1.81 |

| between | 1.40 | 1.40 | 1.41 | ||||

| within | 1.22 | 1.22 | 1.21 | ||||

| Female | overall | 0.59 | 0.49 | 0.59 | 0.49 | 0.59 | 0.49 |

| between | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.49 | ||||

| within | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| EV1 | overall | −4E−03 | 2E−03 | −4E−03 | 2E−03 | −4E−03 | 1E−03 |

| between | 2E−03 | 2E−03 | 1E−03 | ||||

| within | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| EV2 | overall | --6E−04 | 7E−03 | --6E−04 | 7E−03 | −7E−04 | 7E−03 |

| between | 7E−03 | 7E−03 | 7E−03 | ||||

| within | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| EV3 | overall | 5E−04 | 4E−03 | 5E−04 | 4E−03 | 5E−04 | 4E−03 |

| between | 4E−03 | 4E−03 | 4E−03 | ||||

| within | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| EV4 | overall | −1E−04 | 0.001 | −2E−04 | 0.001 | −7E−05 | 0.01 |

| between | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.01 | ||||

| within | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

EV: Eigenvector

GWAS Findings and Polygenic Risk Scores

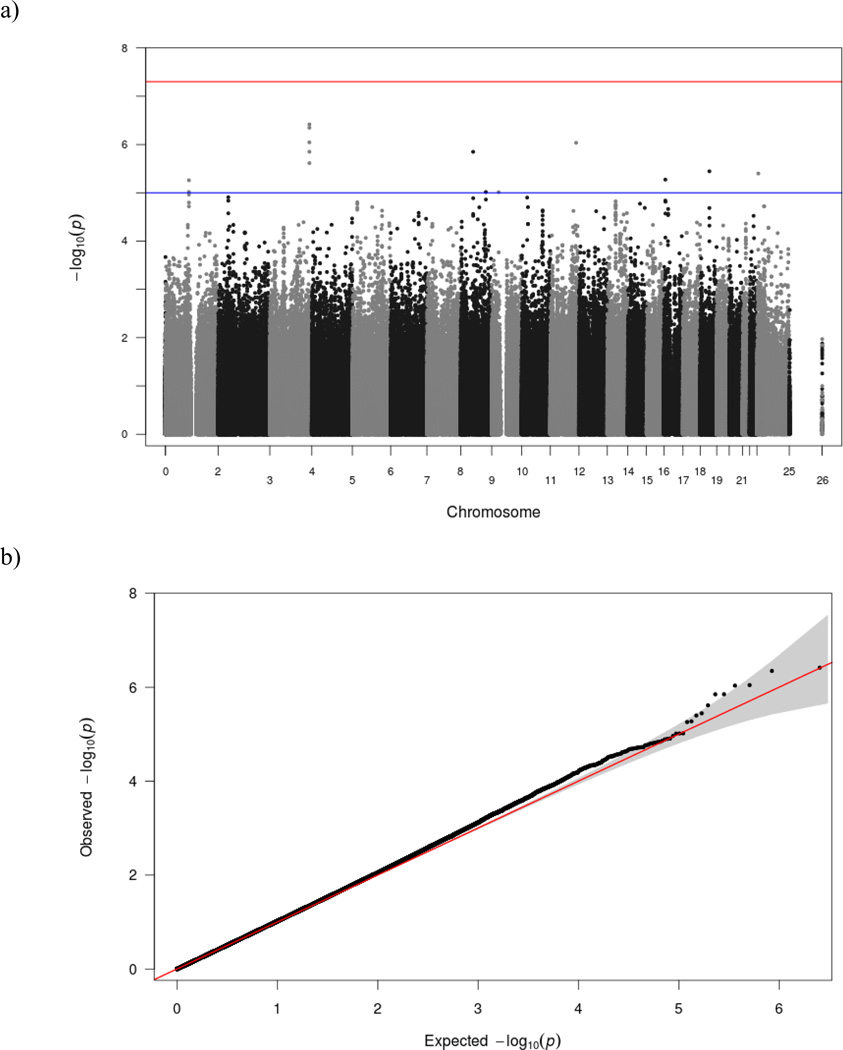

When examining the GWAS results before clustering SNPs by LD we found that overall, no SNPs met the P<5 × 10−08 threshold for genome-wide significance (Figure 1). However, 14 SNPs met criteria for “suggestive association” P<10−05. Five of the 14 SNPs with suggestive association were on chromosome 3, two of which had P<5 × 10−07, the first (rs74751406) which is predicted to be a downstream (<5kb) variant of FETUB and the second (rs7999) which is a missense variant located in FETUB. When clustering SNPs, these two were assigned to the sample group, with rs74751406 set as the index SNP.

Figure 1. Results from the GWAS on CESD score using the discovery sample (N=7,000).

As shown in 1a, no SNPs met criteria for genome-wide significance (the upper reference line), although we found 14 SNPs with suggestive association (the lower reference line), and after reducing this number to 11 by grouping SNPs by empirically suggested LD, these 11 SNPs were selected for inclusion in the PRS. Figure 1b, shows that there are more SNPs with ‘suggestive association’ (P<10−05) than would be expected by chance alone.

SNPs with P<.05 were grouped into clusters based on empirical estimations of LD. The index SNPs for each cluster (those with the lowest P-value) were used to create 5 PRS—one which included all index SNPs with P<.05 (n=37,539), one that included index SNPs with P<10−02(n=8,320), one that included index SNPs with P<10−03(n=998), one that included index SNPs with P<10−04(n=125), and one that included index SNPs with P<10−05(n=11). Using the original discovery sample, we examined the association between the five PRS and mean CESD. As expected, based on R2, the two PRS with the most SNPs (P<.05, n=37,539; and P<.01, n=8,320) had the strongest association with CESD in the discovery sample, while the PRS comprised of only eleven SNPs (all with P<10−02) had the next strongest relationship (results available by request). However, we selected the PRS that included the top 11 SNPs with P<10−05 to test in our replication sample for two reasons. First, inclusion of a large number of SNPs could lead to over-fitting—adding complexity yet increasing bias. Second, while the two PRS made up of SNPs with P<.05 (n=37,539) or P<.01 (n=8,320) did perform better, the degree of increased performance was small relative to the increase in the number of SNPs—suggesting that much of the association with CESD was being captured by the SNPs present in PRS we ultimately selected (SNPs with P<10−05). SNPs included in the final PRS are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of SNPs used to Generate the Final PRs

| Chromosome | SNP | Location | Corresponding Gene | Function | A1 | P-Value | Beta |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | rs74751406 | 186374215 | FETUB | Unknown | A | 3.31E-07 | 0.2772 |

| 3 | rs2292994 | 186359162 | FETUB | Intron | A | 7.20E-07 | 0.2794 |

| 11 | rs11606903 | 121520237 | Intergenic | Unknown | A | 1.42E-06 | 0.5424 |

| 3 | rs1047115 | 186358366 | FETUB | synonymous codon,utr variant 5’ | C | 1.22E-06 | 0.1679 |

| 8 | rs7002316 | 58817444 | Unknown | Unknown | C | 1.14E-06 | 0.1146 |

| 18 | rs58682566 | 43531868 | EPG5 | Intron | G | 4.60E-06 | 0.1964 |

| 23 | rs7060755 | 9049362 | Unknown | Unknown | A | 5.18E-06 | 0.9547 |

| 16 | rs1478708 | 7139879 | RBFOX1 | Intron | G | 5.95E-06 | −0.1651 |

| 1 | rs12411052 | 111158530 | KCNA2 | Intron | G | 4.66E-06 | 0.1886 |

| 8 | rs11989122 | 118827839 | NM_000127.2 | Intron | G | 3.83E-07 | −0.111 |

| 9 | rs13297009 | 32744916 | Unknown | Intergenic | C | 9.71E-06 | −0.1037 |

Replication

For the replication sample, the PRS that included SNPs with P<10−05 (n=11) ranged from −0.036 to 0.120, with a mean of 0.003 and standard deviation of 0.014. However this was standardized to have a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one. Next we examined the association between PRS and mean CESD using OLS regression (Table 3). We found that a one standard deviation increase in the PRS was associated with an approximately .08 point increase in mean CESD (β=0.078, P=.002). This was equivalent to approximately 18% of the effect size of being female. The R2 increase from the model not containing the PRS compared to the one containing PRS was .003 (R2model 1:0.058; R2model 2:0.061). Next, we re-ran this analysis using a Poisson regression in place of the OLS regression to examine whether the distribution of CESD—which is zero-inflated—biased our results. Overall the Poisson regression model produced comparable results to the OLS model (β=0.055, P<.001).

Table 3.

OLS and Poisson Regression of the Association Between PRS and Mean CESD

| Ordinary Least Squares Regression | Poisson Regression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | P-Value | Coefficient | P-Value | |

| Sex (Female=1) | 0.42 | <.001 | 0.33 | <.001 |

| EV1 | 185.52 | <.001 | 91.04 | <.001 |

| EV2 | −4.97 | .623 | −0.33 | .951 |

| EV3 | 8.82 | .602 | 4.46 | .657 |

| EV4 | 3.63 | .320 | 0.75 | .732 |

| Age (wave 8) | −0.002 | .374 | −0.001 | .283 |

| PRS | 0.08 | .002 | 0.06 | <.001 |

| R-squared = 0.061 | Pseudo R-squared=0.027 | |||

EV: Eigenvectors

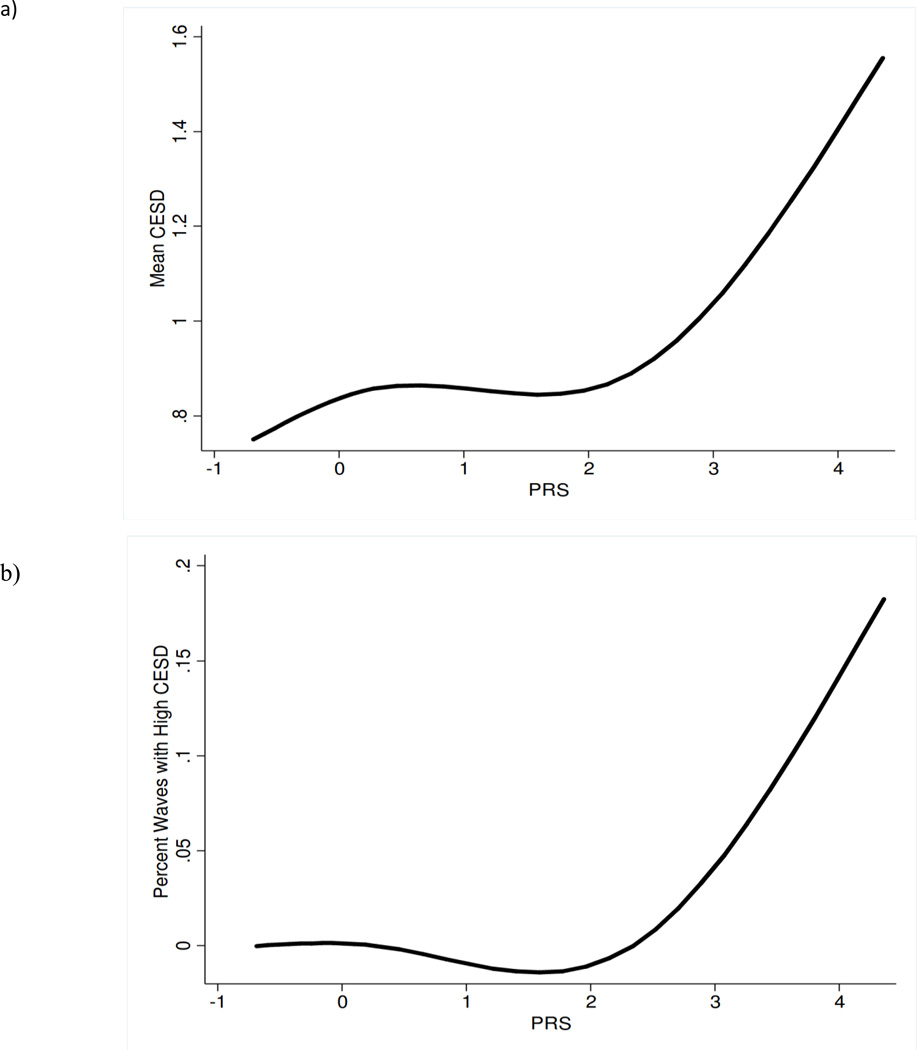

To examine the association between our genetic score and chronicity of high depressive symptoms we used a multinomial logistic regression model to examine whether higher PRS was associated with an increased likelihood of having chronically high CESD—defined as a CESD score of 4 or more—relative to never having high CESD (Table 4). Results showed that a one standard deviation increases in PRS increased the likelihood of having high CESD at every wave by 36% (OR: 1.36, 95%CI: 1.08–1.71). The increased risk of having high CESD for fewer than half the waves (OR: 1.05, 95%CI: 0.97–1.14) and more than half the waves (OR: 1.07, 95%CI: 0.94–1.21)—relative to none of the waves—was not statistically significant, but the increases in the OR were consistent with a dose response between PRS and chronicity. Finally, to examine the dose-response between PRS and both level and chronicity of depressive symptoms, we plotted cubic splines, allowing for 4 knots (Figure 2). We found that for PRS of 2 and above (which corresponds to about 200 participants in our replication sample), both level and chronicity appeared to increase with PRS at a relatively steady rate.

Table 4.

Association Between the PRS and Chronicity of High Depressive Symptoms

| Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval |

|

|---|---|---|

| No waves with high CESD | (reference) | -- |

| High CESD for at least one, but less than half the waves | ||

| Sex (Female=1) | 1.21 | 1.03–1.41 |

| Age (wave 8) | 1.02 | 1.01–1.03 |

| PRS | 1.05 | 0.97–1.14 |

| High CESD for more than half, but not all waves | ||

| Sex (Female=1) | 1.36 | 1.05–1.77 |

| Age (wave 8) | 1.01 | 0.99–1.02 |

| PRS | 1.07 | 0.94–1.21 |

| High CESD for all waves | ||

| Sex (Female=1) | 1.51 | 0.86–2.66 |

| Age (wave 8) | 0.96 | 0.93–0.98 |

| PRS | 1.36 | 1.08–1.71 |

Model was run also adjusting for eigenvectors 1–4

Figure 2. Splines of the Association between the PRS and CESD level and chronicity in the replication sample (N=3,091).

As the PRS increases so do the (levels of) depressive symptoms (Figure 2a), particularly for individuals with a PRS of more than two standard deviations above the mean, for whom mean CESD score rises steadily with an increasing PRS. A very similar trend is seen for the PRS and the chronicity of depressive symptoms (Figure 2b)—measured as the percent of waves that an individual has high CESD (score of four or more)

Discussion

Our study identified a set of SNPs that together were associated with depressive symptoms in two independent samples. The current study moves beyond the one locus approach and instead examined the cumulative effect of multiple loci. While GWASs are designed to examine one SNP at a time without considering an individual’s other genetic characteristics, it is unlikely that a single mutation accounts for the majority of the genetic risk for depression or for other complex traits. Instead, researchers believe that groups of variants, with small individual effects combine to influence an individual’s susceptibility to a given trait (Wray et al., 2007; Wray et al., 2008).

Even in the 1970s, a study examining inheritance patterns in families concluded that depression was most likely a polygenic trait (Baker et al., 1972); however researchers have continued to examine phenotypes like depression using models that do not incorporate information across alleles. In recent years however, many studies, have begun to use polygenic methods to examine complex traits, with relatively good success (Morrison et al., 2007; Kathiresan et al., 2008; Purcell et al.,2009; Bush et al, 2010; Lango et al, 2010; Simonson et al, 2011; Belsky et al., 2013). In the current study, none of our SNPs met genome-wide significance, but 14 (11 after grouping SNPs by LD) met benchmarks for having a “suggested association”. This is consistent with the assumption that the majority of polygenic SNPs are likely to have small individual effect sizes, and thus will not meet genome-wide significance criteria (Yang et al., 2010). By testing for the cumulative associations of multiple SNPs our genetic risk score, which can be thought of as an index of genetic load, was significantly associated with both level and chronicity of depressive symptoms. As far as we know, none of the SNPs we identified have been associated with either depressive symptoms or MDD. Four of the 11 SNPs from our PRS were also examined in the mega-analysis for MDD, yet none were found to be significant. One explanation could be difference in phenotypes used to examine depression—MDD vs depressive symptoms.

The analysis of up to eighteen years of longitudinal data allowed us to develop a depressive phenotype that accounted for both severity and stability of depressive symptoms. While clinical depression phenotypes, like MDD, may reflect a true risk group, if depression is a polygenic trait, one would expect to see a gradient in the level of depressive symptoms with an increasing number of risk alleles (Chang et al., 2014). This is consistent with our results which suggest that both the level of depressive symptoms and chronicity of high CESD increase steadily with increasing PRS, particularly for individuals with PRS two or more standard deviations above the mean. Finally, the examination of chronic depressive symptoms may be more robust in reflecting a more stable depression-related phenotype. While for most individuals depressive symptoms may fluctuate in response to exogenous circumstances, it is possible they reflect a more endogenous trait for individuals with greater genetic susceptibility, and thus may be less influenced by temporal fluctuations caused by changes in an individual’s environment. This was supported by our results that showed a higher PRS increased the likelihood of having continuously high levels of depressive symptoms.

There are limitations to this study which we would like to acknowledge. First, we assessed depressive symptoms with a version of the CESD which asks participants to report presence or absence of eight symptoms as experienced during the prior week. The majority of our sample had low levels of symptoms which may limit our ability to identify variants associated with mild or transient depressive episodes but may have greater sensitivity for detecting individuals with more severe and chronic symptomatology. Second, although our PRS was associated with the number and stability of depressive symptoms, it did not account for anywhere near the 20–40% variation explained by genetic factors based on twin studies (McGue & Christensen, 2003; Jansson et al., 2004; Sullivan et al., 2000; Lubke et al., 2012). Part of this may be due to the fact that only 11 SNPs were included in our PRS. However, the ability to develop more complex PRS (consisting of a higher number of SNPs) relies on our ability to identify and eliminate false-positives. Other explanations for the lower explanatory power of our PRS relative to estimates from twin studies include 1) the possibility that rare variants play a role in pathophysiology of depression and 2) the levels of LD between the SNPs used in our score and the true causal variants. For instance, if our SNPs are only moderately correlated with a causal variant we would expect to see weaker associations between our phenotype and our ‘proxy’ SNP. Nevertheless, the amount of variance explained by our score is similar to what has been found in previous PRS studies of a variety of complex diseases (Dudbridge, 2013). Finally, many HRS participants are spouses, yet given the specific goals of this study, we did not focus on this in our analyses. Nevertheless, given that spouses tend to share environments which may influence depressive symptoms, in moving forward it would be interesting to examine whether differences in PRS are associated with discordance in depressive symptoms between spouses.

Overall, our study was strengthened by our use of a large nationally-representative sample with data on a single cohort assessed over multiple years. In using this we were able to identify a set of SNPs that together influenced both a person’s average level of depressive symptoms and chronicity of high levels of depressive symptoms. These results add to the growing body of recent studies aimed at identifying the molecular basis of vulnerability to experience depressive symptoms.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Institute on Aging: Grants P30AG017265, T32AG0037, R01AG030153. We thank Drs. Jennifer Ailshire, Neil Pendleton, Krisztina Mekli, and James Nazroo for their advice and inputs.

Footnotes

Electronic Resources:

PLINK 1.9, Shaun Purcell, http://pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/purcell/plink/

STATA: StataCorp. 2013. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP.

References

- 1.Belsky DW, Moffitt TE, Baker TB, et al. Polygenic risk and the developmental progression to heavy, persistent smoking and nicotine dependence: evidence from a 4-decade longitudinal study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(5):534–542. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bush WS, Sawcer SJ, de Jager PL, et al. Evidence for polygenic susceptibility to multiple sclerosis–the shape of things to come. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;86:621–625. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.02.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang SC, Glymour MM, Walter S, et al. Genome-wide polygenic scoring for a 14-year long-term average depression phenotype. Brain Behav. 2014;4(2):298–311. doi: 10.1002/brb3.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collins AL, Sullivan PF. Genome-wide association studies in psychiatry: what have we learned? Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202(1):1–4. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.117002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dudbridge F. Power and Predictive Accuracy of Polygenic Risk Scores. PLoS Genetics. 2013;9(3):e1003348. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferrari AJ, Charlson FJ, Norman RE, et al. Burden of Depressive Disorders by Country, Sex, Age, and Year: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. PLoS Med. 2013;10(11):e1001547. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flint J, Kendler KS. The Genetics of Major Depression. Neuron. 2014;81(3):484–503. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A BiolSci Med Sci. 2001;56(3):M146–M156. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Health and Retirement Study. Quality Control Report for Genotypic Data. University of Washington; 2012. http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/sitedocs/genetics/HRS_QC_REPORT_MAR2012.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jansson M, Gatz M, Berg S, et al. Gender differences in heritability of depressive symptoms in the elderly. Psychol Med. 2004;34(3):471–479. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703001375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) JAMA. 2003;289(23):3095–3105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lango Allen H, Estrada K, Lettre G, et al. Hundreds of variants clustered in genomic loci and biological pathways affect human height. Nature. 2010;467:832–838. doi: 10.1038/nature09410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lubke GH, Hottenga JJ, Walters R, et al. Estimating the genetic variance of major depressive disorder due to all single nucleotide polymorphisms. Bio Persp. 2012;72(8):707–709. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manton KG, Stallard E, Vaupe JWl. Methods for Comparing the Mortality Experience of Heterogeneous Populations. Demography. 1981;18(3):389–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGue M, Christensen K. The heritability of depression symptoms in elderly Danish twins: occasion-specific versus general effects. Behav Genet. 2003;33(2):83–93. doi: 10.1023/a:1022545600034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patterson N, Price AL, Reich D. Population structure and eigenanalysis. PLoS Genetics. 2006;2:e190. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020190. 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Purcell SM, Wray NR, Stone JL, et al. Common polygenic variation contributes to risk of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Nature. 2009;460:748–752. doi: 10.1038/nature08185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reddy MS. Depression: The disorder and the burden. Indian J Psychol Med. 2010;32(1):1–2. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.70510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ripke S, Wray NR, Lewis CM, et al. Major Depressive Disorder Working Group of the Psychiatric GWAS Consortium. A mega-analysis of genome-wide association studies for major depressive disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18(4):497–511. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schulz R, Beach SR, Ives DG, et al. Association between Depression and Mortality in Older Adults the Cardiovascular Health Study. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(12):1761–1768. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.12.1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simonson MA, Wills AG, Keller MC, et al. Recent methods for polygenic analysis of genome-wide data implicate an important effect of common variants on cardiovascular disease risk. BMC Med Genet. 2011;12:146. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-12-146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Speliotes EK, Willer CJ, Berndt SI, et al. Association analyses of 249,796 indivdiuals reveal 18 new loci associated with body mass index. Nature Genetics. 2010;42(11):937–948. doi: 10.1038/ng.686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sullivan PF, Neale MC, Kendler KS. Genetic epidemiology of major depression: review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(10):1552–1562. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.10.1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsuang MT, Faraone SV. The Genetics of Mood Disorders. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1990. p. 220. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wray NR, Goddard ME, Visscher PM. Prediction of individual genetic risk to disease from genome-wide association studies. Genome research. 2007;17(10):1520–1528. doi: 10.1101/gr.6665407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wray NR, Goddard ME, Visscher PM. Prediction of individual genetic risk of complex disease. CurrOpin Genet Dev. 2008;18(3):257–263. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang J, Benyamin B, McEvoy BP. Common SNPs explain a large proportion of heritability for human height. Nat Genet. 2010;42(7):565–569. doi: 10.1038/ng.608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]