Abstract

Pyruvate-lactate exchange is mediated by the enzyme lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and is central to the altered energy metabolism in cancer cells. Measurement of exchange kinetics using hyperpolarized 13C NMR has provided a biomarker of response to novel therapeutics. In this study we investigated an alternative in vitro 1H assay, using [3-13C]pyruvate, and compared the measured kinetics with a hyperpolarized 13C-NMR assay, using [1-13C]pyruvate, under the same conditions in human colorectal carcinoma SW1222 cells. The apparent forward reaction rate constants (kPL) derived from the two assays showed no significant difference, and both assays had similar reproducibility (kPL = 0.506 ± 0.054 and kPL = 0.441 ± 0.090 nmol/s/106 cells, (mean ± standard deviation, n = 3); 1H, 13C assays respectively). The apparent backward reaction rate constant (kLP) could only be measured with good reproducibility using the 1H-NMR assay (kLP = 0.376 ± 0.091 nmol/s/106 cells, (mean ± standard deviation, n = 3)). The 1H-NMR assay has adequate sensitivity to measure real-time pyruvate-lactate exchange kinetics in vitro, offering a complementary and accessible assay of apparent LDH activity.

Keywords: 1H NMR, 13C NMR, cancer, hyperpolarized pyruvate, lactate, lactate dehydrogenase activity

Introduction

There is a resurgence of interest in the area of cancer metabolism, including understanding deregulated metabolic pathways, which confer growth advantages to tumors (1). One metabolic adaptation to energy metabolism in cancer is known as the Warburg Effect (2), where glycolysis readily occurs even in the presence of oxygen; this classical hallmark of cancer has been associated with the activity and expression of the key enzyme lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), where increased enzyme activity has been associated with more aggressive disease (3-5). There is a need, therefore, for robust assays of enzyme kinetics, historically carried out by spectrophotometric analysis (6); however, the spectrophotometric assays cannot be performed on whole, viable cells and are consequently an indirect method of evaluating response to targeted therapies (7,8). In contrary to the spectrophotometric technique, NMR has facilitated measurements of real-time enzyme kinetics from viable, whole cells both in vitro and in vivo, and has been used to identify putative therapeutic metabolic targets in cancers (2,9-12).

In this study we have expanded upon an observation by Day et al. (13) and evaluated a 1H-NMR assay of apparent LDH activity, and qualified it against a hyperpolarized 13C NMR measurement using Dynamic Nuclear Polarization (DNP) in the same tumor cell line.

Methods

Cell Preparation for NMR

SW1222 cells were seeded at a density of 3×104 cm−2 and cultured in DMEM medium (Invitrogen, UK) with the addition of 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS, Invitrogen, UK), 1% penicillin and streptomycin (Invitrogen, UK) and 1% L-glutamine (Invitrogen, UK) at 37°C in an atmosphere containing 5% CO2. The floating cell fraction was discarded, and cells were rinsed twice with phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Cells were trypsinised and centrifuged for five minutes at 190 g. Cell pellets were immediately resuspended in 500 μl serum-free medium and NMR studies were carried out within 10 minutes of cell harvesting.

All NMR experiments were performed on an 11.7 T Bruker DMX spectrometer (Bruker Biospin, Germany).

1H-NMR assay

100 μl D2O and 100 μl of a solution containing 50 mM [3-13C]pyruvate (99% isotopically enriched, Sigma-Aldrich, UK) and 50 mM unlabelled, [12C]lactate (in PBS, pH 7) was mixed with a 500 μl cell suspension of 37 ± 5 × 106 SW1222 cells (n=3) in a 5 mm NMR tube. Proton spectra were recorded at 500 MHz, 37°C, with 128 spectra acquired sequentially every 5 s using a 60° pulse-and-acquire sequence (1 transient, 16k time domain points, 10 kHz spectral width, 5 s recovery time). A presaturation pulse (noesygppr1d) was used to achieve good water suppression and a flat spectral baseline.

Hyperpolarized 13C-NMR assay

18 mg [1-13C]pyruvic acid (99% isotopically enriched, Sigma-Aldrich, UK) containing 15 mM trityl free radical OX63 (Oxford Instruments, UK) was polarised in a HyperSense® DNP polariser (Oxford Instruments Molecular Biotools Ltd, UK) for 1 hour; average polarization is typically of the order P = 10%, corresponding to an enhancement factor of ~8000 compared to the thermal signal acquired on the same sample at 11.7 T. The hyperpolarized sample was dissolved in 4 ml aqueous buffer (50 mM sodium lactate, 50 mM sodium hydroxide, 1 mM EDTA) resulting in a 46 ± 3 mM pyruvate solution at pH 7. A volume of this solution (100 μl) was mixed with a 500 μl cell suspension of 35 ± 2 × 106 SW1222 cells (n = 3) in a 5 mm NMR tube. The reaction was monitored at 125 MHz, 37°C, with 128 spectra acquired sequentially every 2.0 s using a 10° pulse-and-acquire sequence (1 transient, 16k time domain points, a 19 kHz spectral width).

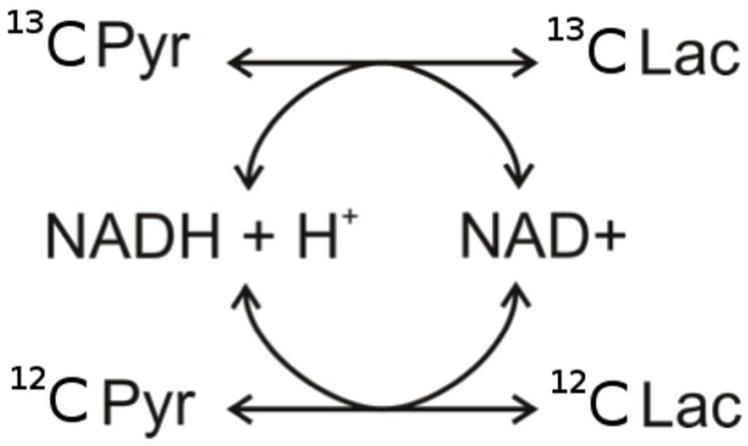

Kinetic Modeling

Lactate dehydrogenase activity can be described by a two-way chemical exchange model (scheme 1), where forward and backward apparent reaction rate constants are given by kPL and kLP respectively. The exchange reaction can be separated into two pools containing either the 13C or 12C spins, the sum of which represents the total pool sizes e.g. P(t) = 13P(t) + 12P(t) and L(t) = 13L(t) + 12L(t). For the 1H assay, the exchange reaction can be written as a set of differential equations:

| (1) |

Where P(t) and L(t) represent the 1H z-magnetizations of pyruvate and lactate signals respectively within the 13C and 12C pools. Whilst the above matrix appears block-diagonal owing to the absence of interconversion between the 13C and 12C they are connected via the presence of the common cofactor NAD(H). At the time-point of the injection of [3-13C]pyruvate (t = 0) the only non-zero pools are 13P(0) and 12L(0) and can be solved to yield time dependencies for [13C] and [12C]pyruvate and lactate signals as follows:

| (2.1) |

| (2.2) |

| (2.3) |

| (2.4) |

Scheme 1.

In the hyperpolarized 13C experiments, the observable magnetization is restricted to only the 13C subspace and the rate equations can be written:

| (3) |

where rP,L = 1/T1(P,L) denote the relaxation rates of hyperpolarized 13C signals of pyruvate and lactate, respectively. The above equation is frequently encountered in NMR relaxation experiments (14) and readily solved by taking the matrix exponential:

| (4) |

Where L is the relaxation matrix in equation (3), D is a diagonal matrix containing the eigenvalues of L, and U is a unitary matrix defined by D = ULU−1. For the case rP = rL the solution is analogous to equations (2.1-2.2) convoluted with an additional exponential decay owing to the loss of magnetization. For the general case rP ≠ rL the above can be solved to give a full analytical expression (13).

Spectral Analysis

Spectra were apodized to 0.5 Hz (1H) or 3 Hz (13C), phase and baseline corrected, and peaks of interest selected and integrated over the time-course of the experiment. The doublet 1H resonance from [3-13C]pyruvate and the 1H resonance from [12C]pyruvate were integrated and the 1H(13C) integrals were summed. Integrals were fitted simultaneously according to the two-way chemical exchange model, equations 2.1 and 2.3, using Matlab (MathWorks, UK) to determine apparent forward kPL and backward kLP rate constants. Rate constants were normalized to cell count for each sample. Integrals of the hyperpolarized [1-13C]-resonances of pyruvate and lactate were flip-angle corrected and simultaneously fitted using Matlab to the full analytical solution (13) of the modified Bloch Equations for two-site exchange.

Statistics

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Differences between rates were identified using a Student’s unpaired t-test with a 5% confidence interval.

Results

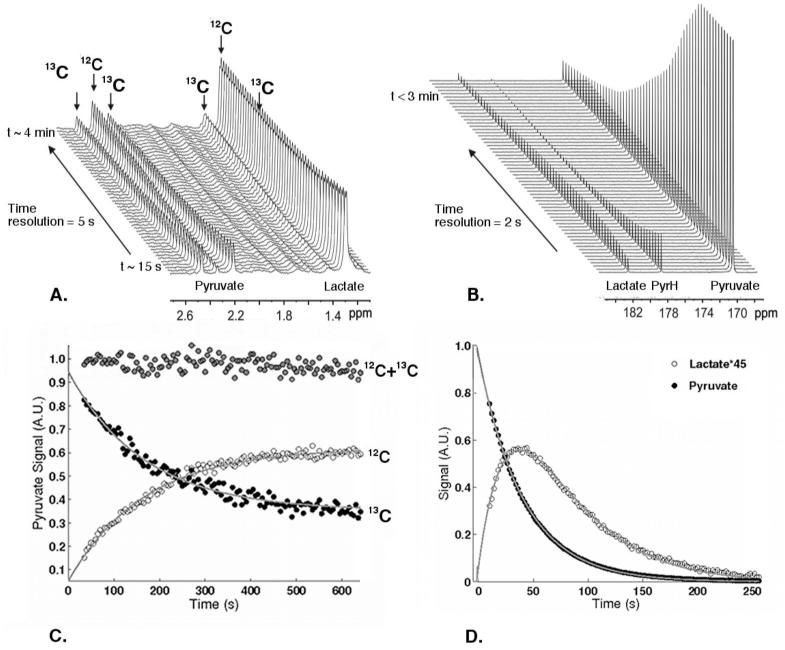

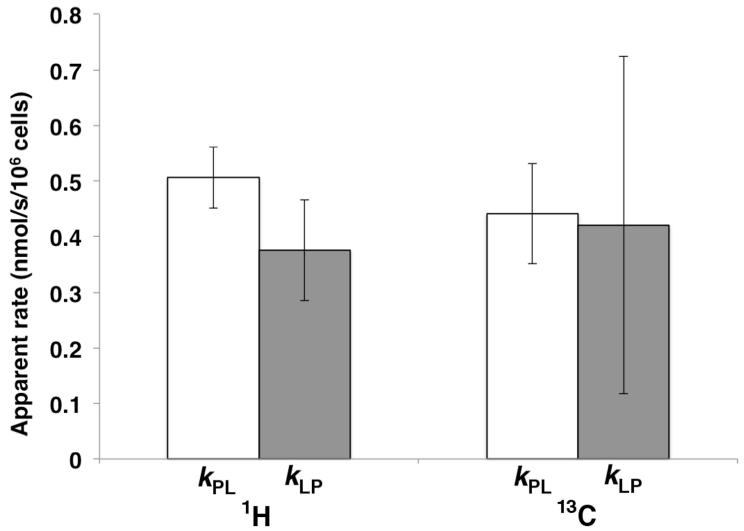

Following the addition of an equimolar solution of [3-13C]pyruvate and [12C]lactate to a suspension of SW1222 cells, a time-dependent decrease in the 1H resonances of both [3-13C]pyruvate (2.4ppm, 1JC3-H3 = 128.7Hz) and [12C]lactate (1.3ppm) was observed with a concomitant increase in the 1H resonances of [12C]pyruvate (2.4ppm) and [3-13C]lactate (1.3ppm, 1JC3-H3 = 128.7Hz), reflecting LDH-mediated pyruvate-lactate exchange (Fig. 1A). The signal-to-noise of the 1H [3-13C]pyruvate peaks at time t = 0 was 31.5 ± 2.8 (n = 3). The 1H-NMR assay allowed the detection of both forward and reverse reactions with apparent reaction rates kPL = 0.506 ± 0.054 nmol/s/106 cells and kLP = 0.376 ± 0.091 nmol/s/106 cells (n = 3), derived from kinetic modeling of the 1H data. There was no significant difference between kPL and kLP (p = 0.10). The sum of the 1H(13C) and 1H(12C) signals was constant over the time series.

Figure 1.

(A) Real-time 1H-NMR and (B) hyperpolarized 13C-NMR assays of pyruvate-lactate exchange in colorectal SW1222 cancer cells and the corresponding time evolution of the spectral integrals (C, D). (C) Integrals of the 1H(12C) peak, open symbols, and 1H(13C) pyruvate peaks, closed symbols, from the 1H assay. (D) Integrals of the hyperpolarized [1-13C]pyruvate peak, closed symbols, and [1-13C]lactate peaks, open symbols, from the 13C assay. The solid lines correspond to the fits from the kinetic models described in the text.

Following the addition of an equimolar solution of hyperpolarized [1-13C]pyruvate and [12C]lactate to a suspension of SW1222 cells, a decrease in the hyperpolarized 13C resonance of pyruvate is observed owing to T1 loss of polarization as well as metabolic conversion, with a concomitant increase in the 13C resonance of [1-13C]lactate, again reflecting LDH-mediated pyruvate-lactate exchange (Fig. 1A). The signal-to-noise of the [13C]pyruvate peak at time t = 0 was measured to be 2186 ± 390 (n=3). Apparent reaction rates kPL = 0.441 ± 0.090 nmol/s/106 cells and kLP = 0.289 ± 0.208 nmol/s/106 cells were derived from kinetic modeling of the 13C data (p = 0.91) (n = 3). A significant uncertainty was associated with the measurement of the reverse reaction rate constant.

There was no significant difference between kPL (p = 0.35) and kLP (p = 0.82), measured from the 1H and 13C assays.

Discussion

In this study we demonstrated that the use of [3-13C]pyruvate in combination with 1H-NMR provides a robust assay to monitor pyruvate-lactate exchange kinetics in vitro. This was compared with the equivalent hyperpolarized 13C-NMR assay. While the signal-to-noise ratio of the hyperpolarized 13C-NMR assay was, at most, 69 times greater than the 1H-NMR assay, the 1H assay provided adequate signal to monitor pyruvate-lactate exchange kinetics in real time. Furthermore, the transient hyperpolarized signal restricts the acquisition window to a few minutes, whereas the 1H assay allows continuous observation of the enzymatic process.

The 1H-NMR assay allows direct, and therefore more accurate, measurement of kLP than the hyperpolarized 13C assay. Accurate determination of kLP from the kinetic modeling of 13C-NMR data is challenging because of the initial condition of an empty [13C]lactate pool coupled with the decay of all the signals owing to relaxation, and the greater number of model fitting parameters in the hyperpolarized assay. This translates into greater uncertainty in kLP estimates from the kinetic modeling of 13C-NMR compared with the 1H assay. The accurate determination of kLP using the hyperpolarized assay has been addressed recently by inverting the magnetization of one of the hyperpolarized metabolite pools, which allows the measurement of forwards and reverse exchange rates (15). A potential solution to allow the direct measurement of kLP using the hyperpolarized assay is to co-polarize [2-13C]pyruvate with [1-13C]lactate, allowing simultaneous detection of both reactions.

Additionally, the measured rate of pyruvate-lactate exchange not only reflects LDH activity (16) but is also dependent on the level of LDH cofactors (NAD/NADH), providing information on cellular energetics, the pool sizes of the injected 13C species, and the pool sizes of (either endogenous or exogenous) 12C metabolites (13,15), as well as the activity and expression of the monocarboxylate transporters, MCT1 and MCT4, that respectively mediate the transport of hyperpolarized pyruvate and lactate into and out of the cells (17). These parameters are often deregulated in cancer, and both assays could be useful to study these important factors, and their modulation, in vitro.

While the 1H-NMR assay demonstrates several attractive features in vitro, hyperpolarized 13C-NMR remains the technique of choice for in vivo measurements, owing to the necessary signal enhancements and large chemical shift range of 13C; it also allows detection of the other metabolic fates of pyruvate, such as the formation of alanine and bicarbonate, biomarkers of alanine transaminase activity and pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) flux respectively (18-20).

Conclusions

The 1H-NMR assay of pyruvate-lactate exchange offered a complementary and accessible measurement of apparent LDH activity in live cancer cells in vitro, with the added value of directly measuring the backward reaction.

Figure 2.

LDH-mediated pyruvate-lactate exchange rates measured in SW1222 cells. (A) Forward and reverse apparent rate constants kPL and kLP measured from the 1H-NMR assay (B) Forward and reverse rate constants kPL and kLP measured from the hyperpolarized 13C-NMR assay. Rates are normalized to cell number in each sample.

Acknowledgement

This work is supported by the Cancer Research UK and EPSRC Cancer Imaging Centre in association with the MRC and Department of Health (England) (refs C1060/A10334). We acknowledge NHS Funding to the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre. Y. Jamin is supported by AstraZeneca.

Abbreviations

- DNP

Dynamic Nuclear Polarization

- LDH

lactate dehydrogenase

- MCT

monocarboxylate transporter

References

- 1.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: The Next Generation. Cell. 2011;144(5):646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heiden MGV, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. Understanding the Warburg Effect: The Metabolic Requirements of Cell Proliferation. Science. 2009;324(5930):1029–1033. doi: 10.1126/science.1160809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwartz MK. Enzymes as prognostic markers and therapeutic indicators in patients with cancer. Clin Chim Acta. 1992;206(1-2):77–82. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(92)90008-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shim H, Dolde C, Lewis BC, Wu CS, Dang G, Jungmann RA, Dalla-Favera R, Dang CV. c-Myc transactivation of LDH-A: Implications for tumor metabolism and growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(13):6658–6663. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.13.6658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bouafia F, Drai J, Bienvenu J, Thieblemont C, Espinouse D, Salles G, Coiffier B. Profiles and prognostic values of serum LDH isoenzymes in patients with haematopoietic malignancies. Bulletin du cancer. 2004;91(7-8):E229–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williamson DH, Lund P, Krebs HA. The redox state of free nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotide in the cytoplasm and mitochondria of rat liver. Biochem J. 1967;103(2):514–527. doi: 10.1042/bj1030514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jamin Y, Smyth L, Robinson SP, Poon ES, Eykyn TR, Springer CJ, Leach MO, Payne GS. Noninvasive detection of carboxypeptidase G2 activity in vivo. NMR Biomed. 2010;24(4):343–350. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beloueche-Babari M, Workman P, Leach MO. Exploiting tumor metabolism for non-invasive imaging of the therapeutic activity of molecularly targeted anticancer agents. Cell Cycle. 2011;10(17):2883–2893. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.17.17192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tennant DA, Duran RV, Gottlieb E. Targeting metabolic transformation for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10(4):267–277. doi: 10.1038/nrc2817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garber K. Oncology’s energetic pipeline. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28(9):888–891. doi: 10.1038/nbt0910-888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dang CV, Le A, Gao P. MYC-Induced Cancer Cell Energy Metabolism and Therapeutic Opportunities. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(21):6479–6483. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feron O. Pyruvate into lactate and back: From the Warburg effect to symbiotic energy fuel exchange in cancer cells. Radiother Oncol. 2009;92(3):329–333. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Day SE, Kettunen MI, Gallagher FA, Hu DE, Lerche M, Wolber J, Golman K, Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH, Brindle KM. Detecting tumor response to treatment using hyperpolarized 13C magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy. Nat Med. 2007;13(11):1382–1387. doi: 10.1038/nm1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bain AD. Chemical exchange in NMR. Prog Nucl Mag Res Sp. 2003;43(3-4):63–103. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kettunen MI, Hu DE, Witney TH, McLaughlin R, Gallagher FA, Bohndiek SE, Day SE, Brindle KM. Magnetization transfer measurements of exchange between hyperpolarized [1-13C]pyruvate and [1-13C]lactate in a murine lymphoma. Magn Reson Med. 2010;63(4):872–880. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ward CS, Venkatesh HS, Chaumeil MM, Brandes AH, VanCriekinge M, Dafni H, Sukumar S, Nelson SJ, Vigneron DB, Kurhanewicz J, James CD, Haas-Kogan DA, Ronen SM. Noninvasive Detection of Target Modulation following Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase Inhibition Using Hyperpolarized (13)C Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. Cancer Res. 2010;70(4):1296–1305. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harris T, Eliyahu G, Frydman L, Degani H. Kinetics of hyperpolarized 13C1-pyruvate transport and metabolism in living human breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(43):18131–18136. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909049106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jensen PR, Karlsson M, Meier S, Duus JO, Lerche MH. Hyperpolarized amino acids for in vivo assays of transaminase activity. Chemistry. 2009;15(39):10010–10012. doi: 10.1002/chem.200901042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Albers MJ, Bok R, Chen AP, Cunningham CH, Zierhut ML, Zhang VY, Kohler SJ, Tropp J, Hurd RE, Yen YF, Nelson SJ, Vigneron DB, Kurhanewicz J. Hyperpolarized 13C lactate, pyruvate, and alanine: noninvasive biomarkers for prostate cancer detection and grading. Cancer Res. 2008;68(20):8607–8615. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Merritt ME, Harrison C, Storey C, Jeffrey FM, Sherry AD, Malloy CR. Hyperpolarized 13C allows a direct measure of flux through a single enzyme-catalyzed step by NMR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(50):19773–19777. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706235104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]