Abstract

Common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) encompasses a heterogeneous group of antibody deficiencies characterized by susceptibility to recurrent infections and sequelae, including bronchiectasis. We investigated the relevance of the lectin complement pathway in CVID patients by analysing ficolin-2 and ficolin-3 serum levels and genotyping single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the FCN2 and FCN3 genes. Our results show that ficolin-2 levels in CVID patients are significantly lower (P < 0·0001) than in controls. The lowest ficolin-2 levels are found in CVID patients with bronchiectasis (P = 0·0004) and autoimmunity (P = 0·04). Although serum levels of ficolin-3 were similar in CVID patients and controls, CVID patients with bronchiectasis again showed lower levels when compared to controls (P = 0·0001). Analysis of single nucleotide polymorphisms in the FCN2 gene confirmed known influences on ficolin-2 serum levels, but did not support a genetic basis for the observed ficolin-2 deficiency in CVID. We found that CVID patients with bronchiectasis have very low levels of ficolin-2. The reason for the deficiency of ficolin-2 in CVID and any possible causal relationship is currently unknown. However, as bronchiectasis is a very important factor for morbidity and mortality in CVID, ficolin-2 could also serve as biomarker for monitoring disease complications such as bronchiectasis.

Keywords: complement, CVID, ficolin-2, ficolin-3, lectin pathway

Introduction

Common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) encompasses a heterogeneous group of antibody deficiencies characterized by susceptibility to recurrent infections and various sequelae and complications, including bronchiectasis, autoimmunity, granulomatous inflammation, lymphoproliferation and malignancy 1.

Mannose binding lectin (MBL) is part of the complement system and acts as a pattern recognition molecule in innate immunity. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the promoter and coding region have been shown to result in low MBL levels, and these genetic defects have been associated with increased susceptibility to infections by numerous studies (reviewed in 2). Although the overall relevance of MBL deficiency is still in debate 3, a modifying role in states of pre-existing deficiency or immaturity of the immune system is undisputed 4. In line with these observations, we and others have studied the involvement of MBL SNPs in the pathogenesis of CVID 5–7, and found them to influence the age of onset 7 and disease complications such as autoimmunity 7 and bronchiectasis 6. In CVID patients MBL serum levels might influence the susceptibility for developing bronchiectasis and the occurrence of other chronic conditions of the respiratory tract, but not on the number of acute respiratory tract infections 6. Furthermore, two additional studies report low levels of MBL in serum of CVID patients with more severe and frequent respiratory tract infections and bronchiectasis 8,9. Thus, while there have been several studies on MBL and CVID, little is known about the possible involvement of a family of related complement proteins, which are termed ficolins.

Like MBL, ficolins are thermolabile proteins and recognize oligosaccharides and polysaccharides on the surface of microorganisms 10. In humans there exist three ficolin members: ficolin-1 (M-ficolin) encoded by FCN1 (chromosome 9q34), ficolin-2 (L-ficolin, hucolin, P35) encoded by FCN2 (chromosome 9q34.3) and ficolin-3 (H-ficolin, Hakata antigen) encoded by FCN3 (chromosome 1p36.11). Ficolins consist of an N-terminal cysteine-rich region, a collagen-like sequence and a C-terminal globular carbohydrate binding domain called fibrinogen-like domain. Ficolins and MBL belong to the innate lectin family of soluble pattern-associated molecular patterns recognizing molecules and activate complement via interaction with MBL-associated serine proteases (MASP). Ficolin-2 is produced mainly in the liver 10, and ficolin-3 is produced in the liver and the lung 10. All ficolins share a basic trimeric substructure that forms oligomers containing four to eight subunits 10. By definition, all ficolins bind acetylated compounds such as N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc), and thus are able to recognize and bind a variety of pathogens or their compounds, respectively 10.

Low ficolin levels predispose to recurrent respiratory tract infection and allergies in children 11,12. There is also an association between low ficolin-2 levels and bronchiectasis 13. High ficolin-3 levels were found in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus 14. A genetic deficiency in FCN3, caused by homozygosity for the SNP rs28357092, resulting in an insertion and frame-shift (FCN3 + 1637delC_L117fs), has been reported recently 15. Interestingly, the reported patient showed many clinical features also common to CVID, including recurrent infections, bronchiectasis, splenomegaly, thrombocytopenia and slightly lower levels of immunoglobulin (Ig)M 15.

A recently published study in a mouse model showed that the ficolin pathway plays an essential role in the defence against Streptococcus pneumoniae 16. In the mice that were deficient in FCN-A, which is related to the human ficolin-3, a worse outcome was observed after infection with S. pneumoniae compared to FCN-A-sufficient mice 16.

The variable clinical presentations in individuals with CVID may be the result of disease-modifying factors, which are as yet only partly known. Some of them might be genetic factors, which explain the risk for developing different comorbidities. As ficolins belong to the MBL family of proteins and have been associated with clinical conditions, such as infection susceptibility, autoimmune disease and bronchiectasis, which are also observed in CVID patients, we decided to analyse the influence of ficolin-2 and ficolin-3 serum levels and SNPs in the FCN-2 and FCN-3 genes in CVID and its clinical manifestations.

Patients and methods

Patient cohort

A total of 239 CVID patients were analysed in this study. One hundred and seven patients were recruited from the Centre for Chronic Immunodeficiency in Freiburg, Germany and 35 patients from the Department of Clinical Immunology and Allergology at St Anne's University Hospital in Brno, Czech Republic. Both ficolin-2 and ficolin-3 serum levels and FCN2 and FCN3 genotypes were determined in these 142 patients. In an additional group of 97 patients, recruited from the Department of Clinical Immunology and Molecular Pathology at Royal Free Hospital in London, UK, only FCN2 and FCN3 genotypes were determined. The control cohort included 120 healthy blood donors, in whom both ficolin-2 and ficolin-3 serum levels and FCN2 and FCN3 genotypes were determined. Informed consent was obtained for all study participants after ethics committee approval (ethical committees of the Albert-Ludwigs-University, Freiburg (no. 78/2001; no. 239/99), the Centre of Cardiosurgery and Transplantation Medicine, Brno (no. 2/2006) and University College, London (no. 04/Q0501/119 and no. 08/H0720/46).

Ficolin-2 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

For the detection of ficolin-2 by ELISA we used a monoclonal mouse anti-human ficolin-2 antibody (IgG1/k, clone 16; Dianova, Hamburg, Germany) as capture (1 : 2000) and a monoclonal mouse anti-human ficolin-2 antibody (IgG2a/k, clone 19; Dianova) as detection antibody (1 : 4000). As secondary reagents we used an alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG2a-specific antibody (1 : 5000) (Dianova) and alkaline phosphatase-conjugated streptavidin (1 : 1875) (Dianova). The optimal antibody concentrations were determined by titration. Recombinant human ficolin-2 (Leu26-Ala313) from the murine myeloma cell line, NS0-derived (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), was used as a standard. Serum samples were diluted 1 : 300. All washing steps were performed with washing buffer [phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)/0·05% Tween 20] using SkanWasher 300 version B. Phosphatase substrate (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) was dissolved at a concentration of 1 mg/ml in diethanolamine buffer (Sigma Aldrich) for developing. The plates were measured at 405 nm against 620 nm on an original MultiSkan Ex ELISA Reader (Thermo Electron Corporation, Fremont, CA, USA). All samples and standards were analysed in duplicate.

Ficolin-3 ELISA

To detect ficolin-3 by ELISA we used a monoclonal mouse anti-human ficolin-3 antibody (IgG1/k, clone FCN334; Dianova) as capture (1 : 32000) and a biotinylated monoclonal mouse anti-human ficolin-3 antibody (IgG1/k, clone FCN334; Dianova) as detection antibody (1 : 32000). As secondary reagent we used alkaline phosphatase-conjugated streptavidin (1 : 1875) (Dianova). The optimal antibody concentrations were determined by titration. Recombinant human ficolin-3 (Lys22-Arg288) from the murine myeloma cell line, NS0-derived (R&D Systems), was used as standard. Serum samples were diluted 1 : 1000. All washing steps were performed with washing buffer (PBS/0·05% Tween 20) using SkanWasher 300 version B. Phosphatase substrate (Sigma Aldrich) was dissolved at a concentration of 1 mg/ml in diethanolamine buffer (Sigma Aldrich) for developing. The plates were measured at 405 nm against 620 nm on an original MultiSkan Ex ELISA Reader (Thermo Electron Corporation). All samples and standards were analysed in duplicate.

MBL ELISA

The analysis of MBL serum level was performed with the MBL ELISA Kit (R&D Systems), according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, ELISA plates were coated with capture goat anti-human MBL antibody and incubated overnight. The samples were diluted 1 : 1600 in PBS and applied on the plate. For detection, a biotinylated goat anti-human MBL antibody was used. The plates were developed with streptavidin–horseradish peroxidase (HRP). All standards and samples were measured in duplicate.

Genotyping of SNPs in FCN2 and FCN3 genes

For genotyping of FCN2 and FCN3 genes we analysed −986A>G (rs3124952), −602G>A (rs3124953) and −4A>G (rs17514136) within the FCN2 gene promoter, T236M (rs17549193) and A258S (rs7851696) in exon 8 of the FCN2 gene and +1637C>delC, L117fs (rs28357092) within exon 5 of the FCN3 gene. The FCN2 promoter region SNPs −986A>G, −602G>A, −4A>G and the +1637C>delC, L117fs SNP within the exon 5 of FCN3 were analysed by restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis (RFLP) using the restriction enzymes ApeK I, Nla III, Ear I (all New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) and ApaI (Fermentas/ThermoFisher Scientific). In brief, gene regions containing the respective SNPs were polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-amplified using primers listed in the Supporting information, Table S1, digested with 1 U of the respective restriction enzyme and visualized by Gelred (Biotium, Hayward, CA, USA) staining after agarose-gel electrophoresis. T236M and A258S genotypes were determined by PCR amplification (for primers and conditions see Supporting information, Table S1) and subsequent direct sequencing on a capillary sequence analyser (ABI 3130XL; Applied Biosystems, Darmstadt, Germany).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the two-sided Student's t-test, χ2 test and Pearson's correlation coefficient calculation with help of GraphPad Prism software version 6·01 (GraphPad Software, Inc. San Diego, CA, USA). Results with P < 0·05 were considered significant.

Results

Analysis of ficolin-2, ficolin-3 and MBL serum levels by ELISA

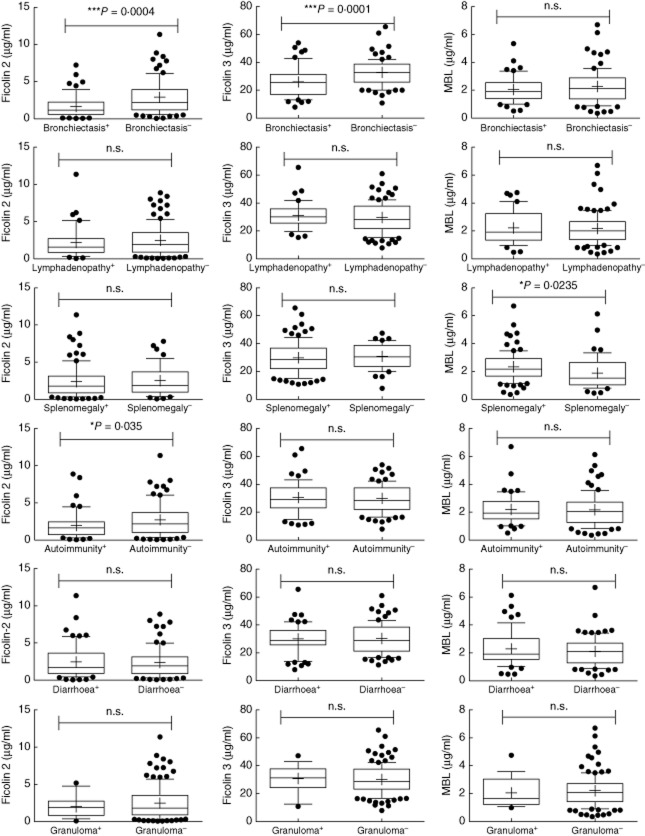

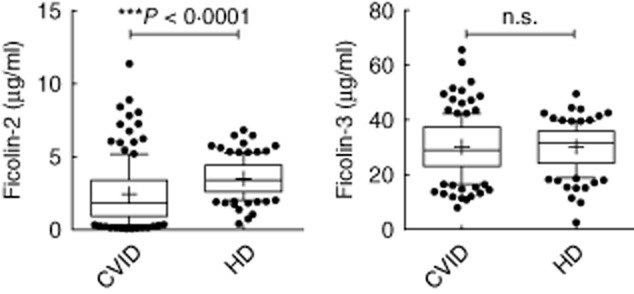

We tested serum samples from a cohort of 142 CVID patients and 120 healthy controls (HD) for the concentrations of ficolin-2, ficolin-3 and MBL by standard sandwich ELISAs. The results showed significantly lower ficolin-2 levels in CVID patients (mean: 2·416 μg/ml, min. 0·052–max. 11·370 μg/ml) when compared to HD (mean: 3·489 μg/ml, min. 0·394–max. 6·820 μg/ml) with P < 0·0001. The ficolin-3 levels were similar in CVID patients (mean: 30·13 μg/ml, min. 7·89–max. 65·58 μg/ml) and controls (mean: 30·21 μg/ml, min. 2·468–max. 49·50 μg/ml) (Fig. 1). We then examined more closely possible associations of ficolin serum levels with the clinical phenotypes in the patients, such as splenomegaly (n = 94), lymphadenopathy (n = 39), bronchiectasis (n = 56), autoimmunity (n = 58), chronic diarrhoea (n = 60) and granulomas (n = 17). CVID patients who suffer from bronchiectasis had significantly lower ficolin-2 serum levels (mean: 1·65 μg/ml, min. 0·052–max. 7·249 μg/ml) compared to the CVID patients who were not suffering from that complication (mean: 2·91 μg/ml, min. 0·063–max. 11·37 μg/ml) with P = 0·0004. The same is true for ficolin-3 serum levels. Patients with bronchiectasis showed significantly lower levels (mean: 25·98 μg/ml, min. 7·89–max. 53·97 μg/ml) compared to CVID patients without bronchiectasis (mean: 32·78 μg/ml, min. 10·83–max. 65·58 μg/ml) with P = 0·0001 (Fig. 2). We further subdivided the CVID patients with bronchiectasis into patients with localized and generalized (more than three lobes affected) bronchiectasis 6 in order to test if ficolin levels also correlated with the extent of bronchiectasis. Although there was a tendency towards lower ficolin-2 and ficolin-3 serum levels in generalized (n = 20; ficolin-2, mean: 1·214 μg/ml; ficolin-3, mean: 24·44 μg/ml) versus localized bronchiectasis (n = 36; ficolin-2, mean: 1·885 μg/ml; ficolin-3, mean: 27·42 μg/ml), the differences were not statistically significant (Supporting information, Fig. S1). For autoimmunity we also found a significant correlation for ficolin-2 serum levels. CVID patients with autoimmune diseases had lower ficolin-2 serum levels (mean: 1·97 μg/ml, min. 0·052–max. 8·883 μg/ml) compared to CVID patients without autoimmunity (mean: 2·72 μg/ml, min. 0·063–max. 11·37 μg/ml) with P = 0·035. For splenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, diarrhoea and granulomas we could not identify any significant differences in serum levels between the two cohorts (Fig. 2). Genotypes leading to low levels of MBL were associated previously with bronchiectasis 6. We therefore analysed MBL serum levels in addition to the ficolin serum levels. We could not find any correlation between low MBL serum levels and bronchiectasis, lymphadenopathy, autoimmunity, diarrhoea and granulomas. However, we found that CVID patients with splenomegaly had higher MBL levels (mean: 2·34 μg/ml, min. 0·35–max. 6·7 μg/ml) than CVID patients without splenomegaly (mean: 1·89 μg/ml, min. 0·45–max. 6·13 μg/ml) with P = 0·0235 (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

Serum ficolin-2 and ficolin-3 levels in common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) patients and healthy donors. Ficolin-2 and ficolin-3 serum levels were analysed in 142 CVID patients and 120 controls each. Box-plots show median, 25th and 75 percentiles, whiskers indicate 10th and 90th percentiles and outliers are shown by filled circles; n.s. = not significant. Statistical analysis was performed by unpaired Student's t-test.

Figure 2.

Serum ficolin-2, ficolin-3 and mannose binding lectin (MBL) levels in association with clinical manifestations. Ficolin-2, ficolin-3 and MBL serum levels were analysed in 142 common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) patients. Box-plots show median, 25th and 75th percentiles, whiskers indicate 10th and 90th percentiles and outliers are shown by filled circles. Plus indicates the mean; n.s. = not significant. Statistical analysis was performed by unpaired Student's t-test.

Analysis of FCN2 and FCN3 gene SNPs

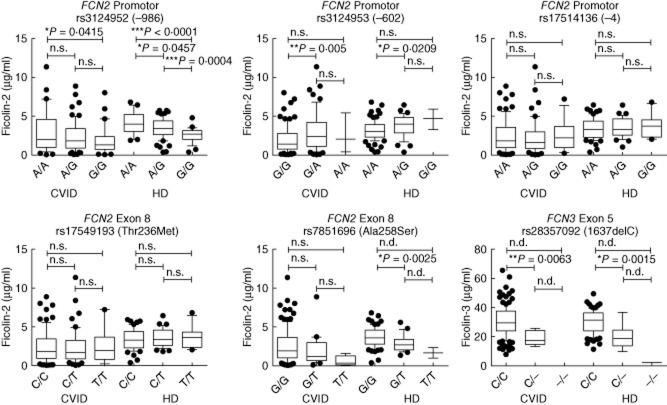

Ficolin-2 and ficolin-3 serum levels are influenced by SNPs in their encoding genes. Therefore, we then looked more closely at the genotype–serotype correlation and analysed the SNPs known to influence ficolin production (rs3124952, rs3124953 and rs17514136 on the promoter of FCN2, rs17549193 and rs7851696 on exon 8 of FCN2 and rs28357092 on exon 5 of FCN3). In both CVID patients and healthy donors, we found the same influences of particular SNPs on ficolin serum levels as described previously 17 (Fig. 3). However, we did not find associations suggesting that the lower ficolin serum levels observed in CVID patients are due to higher frequencies of genotypes associated with lower ficolin serum levels (Table 1). Instead, we found a weak association of the G allele of rs7851696 (Ala258Ser) with CVID. We found that for rs7851696 the homozygous G-genotype is specifically more common in CVID patients (86%) than in the HDs (76%), with P = 0·0291, odds ratio (OR) = 1·933, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1·084–3·447, whereas the heterozygous G/T-genotype is more common in the HDs (23%) than in the CVID patients (12%), with P = 0·0138, OR = 0·4546, 95% CI = 0·2495–0·8280 (Table 1). The G allele, however, is associated with higher ficolin-2 levels (Fig. 3). The lowest ficolin-2 levels were observed in CVID patients suffering from bronchiectasis. Thus, we analysed the association of FCN2 genotypes in CVID patients with and without bronchiectasis and healthy controls (Table 2). Again, there were no associations with genotypes shown previously to cause low ficolin-2 serum levels, but only weak associations of rs17514136 (−4) and rs7851696 (Ala258Ser) (Table 2).

Figure 3.

FCN2/FCN3 genotype–serum level correlation in common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) patients and healthy donors. Box-plots show median, 25th and 75th percentiles, whiskers indicate 10th and 90th percentiles and outliers are shown by filled circles; n.s. = not significant; n.d. = not determined. Statistical analysis was performed by unpaired Student's t-test.

Table 1.

Genotyping of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the FCN2 and FCN3 genes in common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) patients and healthy donors

| CVID |

Healthy donors |

Genotype |

Alleles |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype |

Allele |

Genotype |

Allele |

||||||||||||||

| Gene | SNP | A | a | AA (%) | Aa (%) | aa (%) | A (%) | a (%) | A (%) | Aa (%) | aa (%) | A (%) | a (%) | χ2 | P | OR (5–95%) | P |

| FCN2 | rs3124952 (−986) | A | G | 73 (30) | 114 (48) | 52 (22) | 260 (54) | 218 (46) | 26 (21) | 67 (56) | 28 (23) | 119 (49) | 123 (51) | 3,41 | 0·182 | 1·233 (0·9044–1·680) | 0·206 |

| FCN2 | rs3124953 (−602) | G | A | 138 (58) | 94 (39) | 7 (3) | 370 (77) | 108 (23) | 80 (67) | 37 (31) | 3 (2) | 197 (82) | 43 (18) | 2,68 | 0·261 | 0·7478 (0·5045–1·108) | 0·174 |

| FCN2 | rs17514136 (−4) | A | G | 119 (50) | 98 (41) | 20 (9) | 336 (71) | 138 (29) | 61 (56) | 38 (35) | 10 (9) | 160 (73) | 58 (27) | 1,32 | 0·516 | 0·8826 (0·6158–1·265) | 0·525 |

| FCN2 | rs17549193 (Thr236Met) | C | T | 123 (51) | 100 (42) | 16 (7) | 346 (72) | 132 (28) | 56 (55) | 35 (34) | 11 (11) | 147 (72) | 57 (28) | 2,69 | 0·260 | 1·016 (0·7050–1·465) | 0·925 |

| FCN2 | rs7851696 (Ala258Ser) | G | T | 205 (86) | 29 (12) | 5 (2) | 439 (92) | 39 (8) | 78 (76) | 24 (23) | 1 (1) | 180 (87) | 26 (13) | 7,19 | 0·027 | 1·626 (0·9610–2·751) | 0·087 |

| FCN3 | rs28357092 (1637delC) | C | – | 227 (95) | 11 (5) | 0 (0) | 465 (98) | 11 (2) | 88 (93) | 6 (6) | 1 (1) | 182 (96) | 8 (4) | 2,94 | 0·229 | 1·858 (0·7354–4·695) | 0·200 |

A = major allele; a = minor allele. χ2 = chi-square; OR = odds ratio.

Table 2.

Genotyping of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the FCN2 and FCN3 genes in patients with bronchiectasis

| CVID with bronchiectasis |

CVID without bronchiectasis |

HD |

CVID with BE versus CVID without BE |

CVID with BE versus HD |

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype |

Allele |

Genotype |

Allele |

Genotype |

Allele |

|||||||||||||||||

| Gene | SNP | A | a | AA (%) | Aa (%) | aa (%) | A (%) | a (%) | AA (%) | Aa (%) | aa (%) | A (%) | A (%) | AA (%) | Aa (%) | aa (%) | A (%) | a (%) | χ2 | P | χ2 | P |

| FCN2 | rs3124952 (−986) | A | G | 35 (34) | 51 (49) | 18 (17) | 121 (58) | 87 (42) | 38 (28) | 63 (47) | 34 (25) | 139 (52) | 131 (49) | 26 (21) | 67 (56) | 28 (23) | 119 (49) | 123 (51) | 2·328 | 0·3123 | 4·412 | 0·1101 |

| FCN2 | rs3124953 (−602) | G | A | 62 (60) | 40 (38) | 2 (2) | 164 (79) | 44 (21) | 76 (56) | 54 (40) | 5 (4) | 206 (76) | 64 (24) | 80 (67) | 37 (31) | 3 (2) | 197 (82) | 43 (18) | 0·7834 | 0·6759 | 1·463 | 0·4811 |

| FCN2 | rs17514136 (−4) | A | G | 43 (42) | 48 (47) | 12 (12) | 134 (65) | 72 (35) | 76 (57) | 50 (37) | 8 (6) | 202 (75) | 66 (25) | 61 (56) | 38 (35) | 10 (9) | 160 (73) | 58 (27) | 6·041 | 0·0488 | 4·294 | 0·1169 |

| FCN2 | rs17549193 (Thr236Met) | C | T | 46 (44) | 50 (48) | 8 (8) | 142 (68) | 66 (32) | 77 (57) | 50 (37) | 8 (6) | 204 (76) | 66 (24) | 56 (55) | 35 (34) | 11 (11) | 147 (72) | 57 (28) | 3·857 | 0·1454 | 4·082 | 0·1299 |

| FCN2 | rs7851696 (Ala258Ser) | G | T | 92 (88) | 10 (10) | 2 (2) | 194 (93) | 14 (7) | 113 (84) | 19 (14) | 3 (2) | 245 (91) | 25 (9) | 78 (76) | 24 (23) | 1 (1) | 180 (87) | 26 (13) | 1·143 | 0·5648 | 7·246 | 0·0267 |

| FCN3 | rs28357092 (1637delC) | C | – | 97 (93) | 7 (7) | 0 (0) | 201 (97) | 7 (3) | 130 (97) | 4 (3) | 0 (0) | 264 (99) | 4 (1) | 88 (93) | 6 (6) | 1 (1) | 182 (96) | 8 (4) | n.d. | n.d. | 1·11 | 0·5741 |

A = major allele; a = minor allele, χ2-quare; OR = odds ratio; n.d. = not determined; CVID = common variable immunodeficiency; BE = bronchiectasis.

The SNP rs28357092 is a frame-shift mutation abrogating ficolin-3 protein production. We found several heterozygous CVID patients and HDs demonstrating that heterozygosity for rs2835709 leads to approximately 50% of ficolin-3 production (mean: 18·78 μg/ml, min. 13·18–max. 25·73 μg/ml for the CVID patients and mean: 19·92 μg/ml, min. 9·755–max. 36·78 μg/ml in the HDs) compared to the homozygous C-genotype (mean: 30·63 μg/ml, min. 7·89–max. 65·5 μg/ml for the CVID patients and mean: 30·66 μg/ml, min. 11·44–max. 49·5 μg/ml in the HDs), with P = 0·0063 for the CVID patients and P = 0·0015 for the HDs, respectively (Fig. 3). Interestingly, we found one control homozygous for this frame-shift mutation (Supporting information, Fig. S2). This explained the very low levels of ficolin-3 found in this individual, which were almost 10 times lower than those found in heterozygotes (2·46 μg/ml).

Discussion

In this study we analysed ficolin-2 and ficolin-3 serum levels in a large cohort of antibody-deficient patients, diagnosed clinically with common variable immunodeficiency. Our results show significantly lower levels of ficolin-2 serum levels in the CVID cohort. The lowest ficolin-2 serum levels were found in CVID patients suffering from bronchiectasis. In the CVID cohort with bronchiectasis, 24 of 56 individuals (43%) showed ficolin-2 levels below 1 μg/ml, whereas in the non-bronchiectasis group only 16 of 86 CVID patients (19%) had levels below 1 μg/ml. In contrast, only two of 120 healthy controls (2%) showed levels below 1 μg/ml, and values ranged from 0·39 to 6·8 μg/ml, which is very similar to the ranges reported in control cohorts in previous studies 17–19. A previous study investigated ficolin-2 levels in patients with stable postinfective or idiopathic bronchiectasis (patients with cystic fibrosis and tuberculosis patients were excluded) and also found significantly lower levels in their bronchiectasis cohort 13, which did not include patients with hypogammaglobulinaemia.

There was also a weak association of low ficolin-2 levels with CVID patients showing autoimmune manifestations. Ficolin-2 binds DNA and both ficolin-2 and ficolin-3 recognize dead cells, and thus might be involved in the marking and removal of apoptotic and necrotic cells in the body 20,21, although some of these observations were made only in vitro and at supraphysiological ficolin concentrations. Incomplete or impaired removal of dead cells from the body and disturbances of the highly regulated process of apoptosis are implicated in the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases (reviewed in 22), thus providing a possible link between low ficolin-2 levels in CVID patients suffering from autoimmune complications.

It is well known that several SNPs in the Ficolin genes influence the production and the binding capacity of ficolins (reviewed in 23). Three SNPs (−986A>G, −602G>A, −4A>G) in the promoter of the FCN2 gene influence significantly the amount of ficolin-2 produced, whereas the two exonic SNPs (Thr236Met, Ala258Ser) influence both the amount of produced ficolin-2 and the binding capacity of the produced ficolin-2 23. Lower production of ficolin-2 results from the variant G-allele in rs3124952 (−986A>G) 17, whereas the variant A allele of rs3124953 (−602G>A) 17 and the variant G-allele at position −4 in the promoter region are associated with higher levels of ficolin-2 in serum 12,17. For rs17549193 (Thr236Met) it is known that the C-allele leads to a lower binding capacity of the produced ficolin-2 12 and the variant G-allele in rs7851696 (Ala258Ser) leads to a lower production of ficolin-2, but at the same time to a higher binding capacity of the produced ficolin-2 12,17.

We found similar genotype–serotype correlations for these FCN2 SNPs when we analysed our CVID and HD cohorts. However, we did not find any significant correlations with those FCN2 alleles, which have been described to lead to lower ficolin-2 serum levels, neither for the investigated CVID cohort as a whole nor when the subcohort suffering from bronchiectasis was analysed separately. Instead, we found weak associations with the major allele of rs7851696 (Ala258Ser). Thus, our results suggest that the low ficolin-2 levels observed in CVID patients, especially those with bronchiectasis, are not caused by the known cis-acting SNPs in the FCN2 gene. It should be noted, however, that the ranges of ficolin-2 serum levels associated with each SNP and also their combined haplotypes have wide and overlapping ranges 18,19, and that secondary factors such as age and therapeutic procedures such as chemotherapy may influence ficolin-2 levels 24,25. Thus, other reasons for the observed low ficolin-2 levels in CVID are more likely to exist. One possible explanation is the microbial specificities, which are recognized by ficolin-2. Indeed, ficolin-2 binds many pathogens which are encountered frequently in CVID 1, including Pneumococci, Staphylococcus aureus, Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catharrhalis, Salmonella and Giardia lamblia 18,26–28. In the bronchiectasis context, infections with Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a pathogen recognized by ficolin-2, are more prevalent 29. It was shown recently by two independent investigations that ficolin-2 deficiency and certain FCN2 SNPs may predispose to early colonization with pseudomonas, both in non-cystic and cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis 30. However, these patient cohorts are not as infection-prone as CVID patients to other pathogens recognized by ficolin-2. Thus, although ficolins may react in an acute phase-like manner in acute states of infection 13, chronic and recurrent infections may lead to gradual ficolin-2 consumption in states of immunodeficiency such as CVID, explaining the low ficolin-2 levels we have observed.

In the CVID patients with bronchiectasis we also observed low ficolin-3 levels, and these correlated significantly with ficolin-2 levels in the whole CVID cohort (data not shown). Again, we first investigated a genetic basis for the low ficolin-3 levels. For ficolin-3 it is known that the FCN3 + 1637delC allele results in an early stop codon with no production of ficolin-3 in homozygous individuals and reduced production in heterozygous individuals 15,17 and, again, we observed similar genotype–serotype correlations for FCN3 + 1637delC when we analysed our CVID and HD cohorts. However, we did not find any significant correlation when the subcohort suffering from bronchiectasis was analysed separately for association with FCN3 + 1637delC, although we found one individual homozygous for FCN3 + 1637delC in the healthy control cohort. This is an interesting finding, as so far only three cases of complete ficolin-3 deficiency 15,31,32 have been described and our case seems to be the first in an unaffected healthy person, indicating that ficolin-3 deficiency is not 100% penetrant. The relatively high frequencies of heterozygous carriers of FCN3 + 1637delC in our study (0·02 in CVID and 0·04 in HD) and in a Polish population 31, as well as the presence of additional genetic defects in one of the cases of genetic ficolin-3 deficiency 31, support this assumption. Other explanations for the observed low ficolin-3 levels in CVID patients with bronchiectasis are the correlation and possible co-regulation of ficolin-2 and ficolin-3 levels, which have been described previously 24,31,33, and progressive organ damage in bronchiectasis resulting in lower production of ficolin-3, which is produced in the lungs by alveolar epithelial cells 10.

In conclusion, we found that CVID patients with bronchiectasis have very low levels of ficolin-2 and reduced levels of ficolin-3, which are two important members of the lectin pathway with newly emerging roles in respiratory immunity. Currently, we cannot determine the molecular cause for the deficiency of ficolins in the CVID cohort but we can speculate on a relationship with the clinical complication of bronchiectasis. However, as bronchiectasis and overall respiratory immunity and functions are very important factors for prognosis, morbidity and mortality in CVID 9,34,35, ficolins could also serve as biomarkers for monitoring disease complications and the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions in addition to existing modalities. A better understanding of the exact role of ficolins in respiratory immunity and their regulation will help to assess the relevance of the ficolin pathway in CVID and other disorders in the future.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) SFB 620 IRTG-IMM project Z3 (MLM) and SFB 620 project C7 (US), EUROPADnet HEALTH-F2–2008–201549 of the European Union and CEITEC - CZ.1·05/1·1.00/02·0068 (JL) and by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF 01EO1303) (U. S.). The authors are responsible for the contents of this publication.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Author contributions

M. L. M. performed experiments and wrote the paper, K. M. performed experiments; I. M., S. G. and D. G. provided and reviewed clinical data of patients and performed statistical analysis; J. L. and B. G. provided patient samples and clinical data and wrote the paper; U. S. wrote the paper and designed the study.

Supporting Information

Fig. S1. Serum ficolin-2 and ficolin-3 levels in patient subgroups with localized or generalized bronchiectasis (BE).

Fig. S2. FCN3 exon 5 rs28357092 (1637delC) genotype.

Table S1. Primer sequences and conditions.

References

- Gathmann B, Mahlaoui N, Gerard L. Clinical picture and treatment of 2212 patients with common variable immunodeficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:116–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.12.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen DP. Mannose-binding lectin deficiency and respiratory tract infection. J Innate Immun. 2010;2:114–122. doi: 10.1159/000228159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanova JL, Abel L. Human mannose-binding lectin in immunity: friend, foe, or both? J Exp Med. 2004;199:1295–1299. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner MW. The role of mannose-binding lectin in health and disease. Mol Immunol. 2003;40:423–429. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(03)00155-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aghamohammadi A, Foroughi F, Rezaei N, Dianat S, Solgi G, Amirzargar AA. Mannose-binding lectin polymorphisms in common variable immunodeficiency. Clin Exp Med. 2009;9:285–290. doi: 10.1007/s10238-009-0049-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litzman J, Freiberger T, Grimbacher B. Mannose-binding lectin gene polymorphic variants predispose to the development of bronchopulmonary complications but have no influence on other clinical and laboratory symptoms or signs of common variable immunodeficiency. Clin Exp Immunol. 2008;153:324–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2008.03700.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullighan CG, Marshall SE, Welsh KI. Mannose binding lectin polymorphisms are associated with early age of disease onset and autoimmunity in common variable immunodeficiency. Scand J Immunol. 2000;51:111–122. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2000.00697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen P, Permin H, Andersen V. Deficiency of somatic hypermutation of the antibody light chain is associated with increased frequency of severe respiratory tract infection in common variable immunodeficiency. Blood. 2005;105:511–517. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregersen S, Aalokken TM, Mynarek G. Development of pulmonary abnormalities in patients with common variable immunodeficiency: associations with clinical and immunologic factors. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;104:503–510. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2010.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushita M. Ficolins: complement-activating lectins involved in innate immunity. J Innate Immun. 2010;2:24–32. doi: 10.1159/000228160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cedzynski M, Atkinson AP, St Swierzko A. L-ficolin (ficolin-2) insufficiency is associated with combined allergic and infectious respiratory disease in children. Mol Immunol. 2009;47:415–419. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cedzynski M, Nuytinck L, Atkinson AP. Extremes of L-ficolin concentration in children with recurrent infections are associated with single nucleotide polymorphisms in the FCN2 gene. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007;150:99–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2007.03471.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DC, Chalmers JD, MacDonald SL. Stable bronchiectasis is associated with low serum L-ficolin concentrations. Clin Respir J. 2009;3:29–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-699X.2008.00105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen T, Munthe-Fog L, Garred P, Jacobsen S. Serum levels of ficolin-3 (Hakata antigen) in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:757–759. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.080361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munthe-Fog L, Hummelshoj T, Honore C, Madsen HO, Permin H, Garred P. Immunodeficiency associated with FCN3 mutation and ficolin-3 deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2637–2644. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo Y, Takahashi M, Iwaki D. Mice deficient in ficolin, a lectin complement pathway recognition molecule, are susceptible to Streptococcus pneumoniae infection. J Immunol. 2012;189:5860–5866. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummelshoj T, Munthe-Fog L, Madsen HO, Fujita T, Matsushita M, Garred P. Polymorphisms in the FCN2 gene determine serum variation and function of ficolin-2. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:1651–1658. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DC, Chalmers JD. Human L-ficolin (ficolin-2) and its clinical significance. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2012;2012:138797. doi: 10.1155/2012/138797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munthe-Fog L, Hummelshoj T, Hansen BE. The impact of FCN2 polymorphisms and haplotypes on the Ficolin-2 serum levels. Scand J Immunol. 2007;65:383–392. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2007.01915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honore C, Hummelshoj T, Hansen BE, Madsen HO, Eggleton P, Garred P. The innate immune component ficolin 3 (Hakata antigen) mediates the clearance of late apoptotic cells. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:1598–1607. doi: 10.1002/art.22564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen ML, Honore C, Hummelshoj T, Hansen BE, Madsen HO, Garred P. Ficolin-2 recognizes DNA and participates in the clearance of dying host cells. Mol Immunol. 2007;44:856–865. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz LE, Lauber K, Schiller M, Manfredi AA, Herrmann M. The role of defective clearance of apoptotic cells in systemic autoimmunity. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010;6:280–289. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garred P, Honore C, Ma YJ. The genetics of ficolins. J Innate Immun. 2010;2:3–16. doi: 10.1159/000242419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DC, McLintock LA, Allan EK. No strong relationship between mannan binding lectin or plasma ficolins and chemotherapy-related infections. Clin Exp Immunol. 2003;134:279–284. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2003.02284.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallenbach S, Thiel S, Aebi C. Serum concentrations of lectin-pathway components in healthy neonates, children and adults: mannan-binding lectin (MBL), M-, L-, and H-ficolin, and MBL-associated serine protease-2 (MASP-2) Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2011;22:424–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2010.01104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Osses I, Ansa-Addo EA, Inal JM, Ramirez MI. Involvement of lectin pathway activation in the complement killing of Giardia intestinalis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;395:382–386. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krarup A, Sorensen UB, Matsushita M, Jensenius JC, Thiel S. Effect of capsulation of opportunistic pathogenic bacteria on binding of the pattern recognition molecules mannan-binding lectin, L-ficolin, and H-ficolin. Infect Immun. 2005;73:1052–1060. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.2.1052-1060.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushita M, Endo Y, Taira S. A novel human serum lectin with collagen- and fibrinogen-like domains that functions as an opsonin. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:2448–2454. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.5.2448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Koh J, Lu J. Local inflammation induces complement crosstalk which amplifies the antimicrobial response. PLOS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000282. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haerynck F, Van Steen K, Cattaert T. Polymorphisms in the lectin pathway genes as a possible cause of early chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa colonization in cystic fibrosis patients. Hum Immunol. 2012;73:1175–1183. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2012.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalski M, Szala A, St Swierzko A. H-ficolin (ficolin-3) concentrations and FCN3 gene polymorphism in neonates. Immunobiology. 2012;217:730–737. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlapbach LJ, Thiel S, Kessler U, Ammann RA, Aebi C, Jensenius JC. Congenital H-ficolin deficiency in premature infants with severe necrotising enterocolitis. Gut. 2011;60:1438–1439. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.226027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlapbach LJ, Kessler U, Thiel S. M-ficolin in the neonatal period: associations with need for mechanical ventilation and mortality in premature infants with necrotising enterocolitis. Mol Immunol. 2009;46:2597–2603. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinti I, Soresina A, Spadaro G. Long-term follow-up and outcome of a large cohort of patients with common variable immunodeficiency. J Clin Immunol. 2007;27:308–316. doi: 10.1007/s10875-007-9075-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thickett KM, Kumararatne DS, Banerjee AK, Dudley R, Stableforth DE. Common variable immune deficiency: respiratory manifestations, pulmonary function and high-resolution CT scan findings. Q J Med. 2002;95:655–662. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/95.10.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. Serum ficolin-2 and ficolin-3 levels in patient subgroups with localized or generalized bronchiectasis (BE).

Fig. S2. FCN3 exon 5 rs28357092 (1637delC) genotype.

Table S1. Primer sequences and conditions.