Abstract

Airway inflammatory diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma are associated with elevated expression of interleukin-32 (IL-32), a recently described cytokine that appears to play a critical role in inflammation. However, so far, the regulation of pulmonary IL-32 production has not been fully established. We examined the expression of IL-32 by tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) in primary human lung fibroblasts. Human lung fibroblasts were cultured in the presence or absence of TNF-α and/or other cytokines/Toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands or various signalling molecule inhibitors to analyse the expression of IL-32 by quantitative RT-PCR and ELISA. Next, activation of Akt and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) signalling pathways was investigated by Western blot. Interleukin-32 mRNA of four spliced isoforms (α,β,γ and δ) was up-regulated upon TNF-α stimulation, which was associated with a significant IL-32 protein release from TNF-α-activated human lung fibroblasts. The combination of interferon-γ and TNF-α induced enhanced IL-32 release in human lung fibroblasts, whereas IL-4, IL-17A, IL-27 and TLR ligands did not alter IL-32 release in human lung fibroblasts either alone, or in combination with TNF-α. Furthermore, the activation of Akt and JNK pathways regulated TNF-α-induced IL-32 expression in human lung fibroblasts, and inhibition of the Akt and JNK pathways was able to suppress the increased release of IL-32 to nearly the basal level. These data suggest that TNF-α may be involved in airway inflammation via the induction of IL-32 by activating Akt and JNK signalling pathways. Therefore, the TNF-α/IL-32 axis may be a potential therapeutic target for airway inflammatory diseases.

Keywords: cytokines, fibroblasts, inflammation

Introduction

Airway inflammatory diseases, including respiratory infections, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and pulmonary fibrosis, represent a major public health problem associated with significant morbidity and mortality in the world.1,2 Deregulated airway inflammation is a central pathophysiological feature of airway inflammatory diseases, which can promote tissue damage, airway remodelling, and consequently lead to a decline in lung function.3,4 Hence, it is critical to understand airway inflammation in acute and chronic airway diseases. Airway inflammation is initiated, amplified and maintained by, at least partially, a complicated network of inflammatory cytokines,5,6 including interleukin-32 (IL-32).7

Interleukin-32 is known as a pro-inflammatory cytokine produced mainly by natural killer cells, T lymphocytes, epithelial cells and blood monocytes in response to many stimuli such as IL-2, interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and respiratory viruses.8–10 Interleukin-32 is a strong inducer of other pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and macrophage inflammatory protein-2 by activation of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38 MAPK) signalling pathways.8,11 Several reports have suggested a role of IL-32 in COPD, as its level positively correlated with TNF-α, CD8+ cells, phospho-p38 MAPK and negatively with 1-second forced expiratory volume values.12 Interleukin-32 was also detectable in induced sputum from patients with asthma and serum levels were significantly higher in patients with asthma compared with those seen in healthy controls and were correlated with response to asthma treatment.13 Moreover, a common IL-32 genotype, rs12934561, has been reported to associate with the risk of acute lung injury as well as the need for prolonged mechanical ventilatory support.14 These findings suggest that IL-32 is not only involved in initiating inflammatory and cellular events that result in airway inflammation, but also participates in determining the severity of pulmonary dysfunction associated with airway inflammatory diseases. However, the mechanism by which the expression of pulmonary IL-32 is regulated during airway inflammation has not been fully elucidated.

Tumour necrosis factor-α is one of the crucial cytokines regulating the development of airway inflammation.15,16 We and other groups have shown that TNF-α is up-regulated in a variety of airway inflammatory diseases, including pulmonary tuberculosis, COPD and asthma.16,17 Moreover, we have demonstrated that TNF-α could modulate the expression of cytokines, chemokines and adhesion molecules by airway epithelial cells and pulmonary fibroblasts.16,18 However, the mechanism by which this cytokine may influence pulmonary IL-32 expression remains unknown. In the current study, we showed for the first time that TNF-α could induce IL-32 mRNA expression and protein release from primary human lung fibroblasts (HLF) via the activation of Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and Akt signalling pathways.

Materials and methods

Reagents

Recombinant human IL-4, IL-17A, IL-27, IFN-γ and TNF-α were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Ultra-purified lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from Escherichia coli K12 strain without any contamination by lipoprotein, R837 (Imiquimod, a synthetic antiviral molecule), ssRNA and CpG DNA, for Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), TLR7, TLR8 and TLR9 were purchased from InvivoGen Corp. (San Diego, CA), while flagellin for TLR5 was from Calbiochem Corp. (San Diego, CA). Poly I-C (TLR3 ligand) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (St Louis, MO), and peptidoglycan for TLR2 from Fluka Chemie GmbH (Buchs, Switzerland). Mouse anti-phospho-JNK, anti-phospho-Akt, anti-JNK and anti-Akt monoclonal antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology Corp. (Beverly, MA). IκB-α phosphorylation inhibitor BAY11-7082, extracellular signal-regulated kinase inhibitor U0126, JNK inhibitor SP600125, p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580, phosphatidylinositol 3-OH kinase (PI3K) inhibitor LY294002 and Janus kinase inhibitor AG490 were purchased from Calbiochem Corp. SB203580 and LY294002 were dissolved in water, while PD98059, SP600125, AG490 and BAY117082 were dissolved in DMSO. In all the cell culture assays, the final concentration of DMSO was 0·1% (volume/volume).

Human lung fibroblast culture

Primary HLF were purchased from ScienCell Research Laboratories (Carlsbad, CA) and cultured in fibroblast cell growth medium according to the manufacturer's instructions. Fibroblast cell growth medium contains essential and non-essential amino acids, vitamins, organic and inorganic compounds, hormones, growth factors, trace minerals and a low concentration of fetal bovine serum (2%). The medium is HEPES and bicarbonate buffered and has a pH of 7·4 when equilibrated in an incubator with an atmosphere of 5% CO2/95% air. Fibroblast cell growth medium provides a defined and optimally balanced nutritional environment that selectively promotes proliferation and growth of normal human fibroblasts in vitro (http://www.sciencellonline.com/site/productInformation.php?keyword=2301). The HLF were washed in PBS and serum-deprived for 24 hr before stimulation.

Endotoxin-free solutions

Cell culture medium was purchased from Gibco Invitrogen Corporation (Carlsbad, CA) free of detectable LPS (< 0·1 EU/ml). No solution contained detectable LPS, as determined by the Limulus amoebocyte lyase assay (sensitivity limit 12 pg/ml; Biowhittaker, Inc., Walkersville, MD).

3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2, 5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay

Human lung fibroblasts (2 × 104 cells/0·2 ml) were inoculated into a 96-well plate. Various inhibitors at serial concentrations were added to the cells. After 48 hr incubation, MTT (50 mg; Sigma-Aldrich Co.) was added to each well and incubated for 2 hr.

Viable cells took up MTT and reduced it to dark blue, water-insoluble formazan by mitochondrial dehydrogenase, which reflected the normal function of mitochondria and cell viability. The cells were then lysed with DMSO to yield the colour solution. The absorbance at 550 nm was measured to quantify the viable cells.

PCR analysis

The sequences of PCR primers are described in Table1. For quantitative analysis, an aliquot of cDNA was used as a template for real-time PCR using an SYBR Green MasterMix (Takara Bio Inc., Otsu, Japan) on an ABI PRISM 7000 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) with SYBR green I dye as the amplicon detector. The gene for GAPDH was amplified as an endogenous reference. Quantification was determined using both a standard curve and comparative ΔΔCt methods.

Table 1.

Primers used in real-time polymerase chain reaction

| Primer | Sense | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| IL-32α | Forward | CCTTGGCTCCTTGAACTTTTG |

| Reverse | CTGTCCACGTCCTGATTCTG | |

| IL-32β | Forward | CTGAAGGCCCGAATGCACCAG |

| Reverse | GCAAAGGTGGTGTCAGTATC | |

| IL-32γ | Forward | TGACATGAAGAAGCTGAAGGC |

| Reverse | CATGACCTTGTCACAAAAGCTC | |

| IL-32δ | Forward | TCTCTGGTGACATGAAGAAGCT |

| Reverse | GCAAAGGTGGTGTCAGTATC | |

| GAPDH | Forward | GGTGAAGGTCGGAGTCAACGGA |

| Reverse | GAGGGATCTCGCTCGCTCCTGGAAGA |

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

The amounts of IL-32 present in culture supernatants were determined using a specific human IL-32γ ELISA kit (MyBioSource, San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The sensitivity in this assay was 1·0 pg/ml.

Western blot analysis

Cells (1 × 106) were washed with ice-cold PBS and lysed in 0·2 ml lysis buffer (20 mm Tris–HCl, pH 8·0, 120 mm NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 10 mm EDTA, 1 mm EGTA, 0·05% 2-mercaptoethanol, 1 × protease inhibitors). Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 14 000 g for 15 min, and the supernatant was boiled in Laemmli sample buffer (Bio-Rad Laboratory, Hercules, CA) for 5 min. An equal amount of protein (10 μg) was subjected to SDS–10% PAGE before blotting onto a PVDF membrane (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ). The membrane was blocked with 5% skimmed milk in Tris-buffered saline with 0·05% Tween-20 for 1 hr at room temperature, and probed with anti-human phospho-JNK and total JNK, anti-human phospho-Akt and total Akt at 4° overnight. After washing, the membrane was incubated with corresponding secondary donkey anti-rabbit or sheep anti-mouse antibodies coupled to horseradish peroxidase (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) for 1 hr at room temperature. Antibody–antigen complexes were then detected using an ECL chemiluminescent detection system. To assess protein expression, band intensity was quantified using ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD).

Statistical analysis

All data were expressed as mean ± SD. Differences between groups were assessed by one-way analysis of variance (anova) or unpaired t-test. Any difference with P-values < 0·05 was considered significant. When anova indicated a significant difference, a Bonferroni post hoc test was then used to assess the difference between groups. All analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (spss) statistical software for Windows, version 10.1.4 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Effects of TNF-α on IL-32 synthesis and release by activated HLF

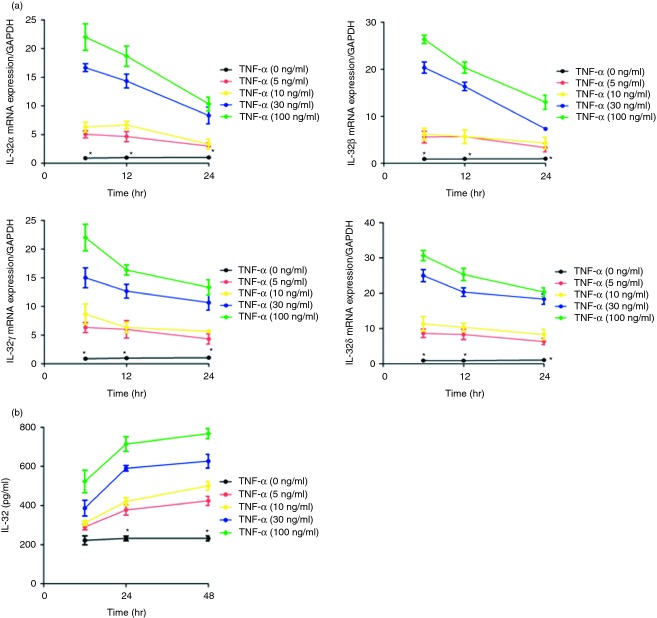

Figure1(a) shows the kinetics and dose response of TNF-α-inducing effects on the mRNA expression of IL-32α,β,γ and δ. The TNF-α (5–100 ng/ml) could significantly up-regulate the expression of IL-32α,β,γ and δ transcripts in HLF, with a mean increase of 17-, 20-, 15- and 25-fold after stimulation for 6 hr at the concentration of 30 ng/ml, respectively. By using an ELISA test that detected IL-32, we further observed that TNF-α (5–100 ng/ml) induced IL-32 release by HLF, especially at 24 hr and 48 hr, compared with non-activated cells (Fig.1b). Therefore, we chose this incubation time (24 hr) and concentration (30 ng/ml) of TNF-α in the following studies.

Figure 1.

Expression of the interleukin-32 (IL-32) gene and protein in primary human lung fibroblasts (HLF) activated by tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α). (a) IL-32 α,β,γ and δmRNA levels were determined using quantitative RT-PCR in HLF activated by TNF-α (0–100 ng/ml) for 0–24 hr; (b) IL-32 release in culture supernatants was determined with ELISA after stimulation with TNF-α (0–100 ng/ml) for 0–48 hr. Results are expressed as the arithmetic mean ± SD from three independent experiments. *P < 0·05 when compared with cells activated by TNF-α (5–100 ng/ml).

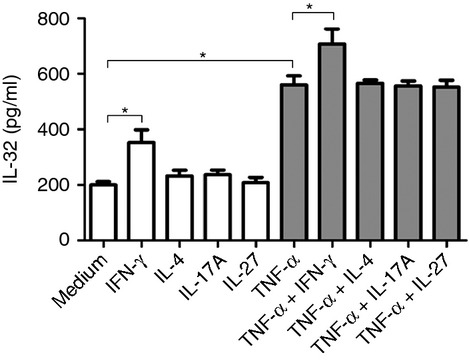

Effects of TNF-α on IL-32 in cytokine-treated HLF

The inflammatory environment is complex in airway inflammatory diseases, because most of cytokines are present in the airways and can interact with each other.5 We investigated whether TNF-α modulates the release of IL-32 in HLF stimulated with a T helper type 1 (Th1) cytokine (IFN-γ), Th2 cytokine (IL-4), Th17 cytokine (IL-17A), or anti-inflammatory cytokine (IL-27). Interferon-γ (5–50 ng/ml) induced a significant release of IL-32, while IL-4, IL-17A and IL-27 (all 5–100 ng/ml) could not induce IL-32 production from HLF (see Supporting information, Fig. S1). Moreover, concomitant stimulation of HLF with IFN-γ (50 ng/ml) and TNF-α (30 ng/ml) resulted in a strong induction of IL-32 release as compared with stimulation with only one of these cytokines (Fig.2). However, IL-4, IL-17A or IL-27 did not affect IL-32 release from HLF in combination with TNF-α.

Figure 2.

Effects of a T helper type 1 (Th1) cytokine (interferon-γ; IFN-γ), Th2 cytokine (interleukin-4; IL-4), Th17 cytokine (IL-17A), or anti-inflammatory cytokine (IL-27) on tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) -induced IL-32 release in human lung fibroblasts (HLF). HLF were activated as indicated (IFN-γ, 50 ng/ml; IL-4, 100 ng/ml; IL-17A, 100 ng/ml; IL-27, 100 ng/ml; TNF-α, 30 ng/ml) for 24 hr, and IL-32 protein levels in supernatants were determined by ELISA. Results are expressed as the arithmetic mean ± SD from three independent experiments. *P < 0·05 when compared between groups denoted by horizontal lines.

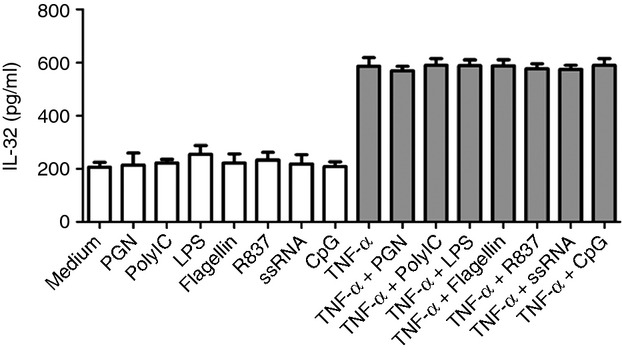

Effects of TLR triggering on TNF-α-induced IL-32 release in HLF

We also studied the effect of a concomitant stimulation of TNF-α and seven TLR ligands: peptidoglycan (TLR2 ligand), poly IC (TLR3 ligand), LPS (TLR4 ligand), flagellin (TLR5 ligand), R837 (TLR7 ligand), ssRNA (TLR8 ligand), or CpG (TLR9 ligand). A dose titration of the different TLR agonists (from 100 ng to 1 μg/ml) did not induce IL-32 release from HLF (see Supporting information, Fig. S2), and these TLR ligands (all 1 μg/ml) did not alter IL-32 release in HLF stimulated with TNF-α (Fig.3).

Figure 3.

Effects of Toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands on tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) -induced interleukin-32 (IL-32) release in human lung fibroblasts (HLF). HLF were activated as indicated (TLR ligands, all 1 μg/ml; TNF-α, 30 ng/ml) for 24 hr, and IL-32 protein levels in supernatants were determined by ELISA. Results are expressed as the arithmetic mean ± SD from three independent experiments.

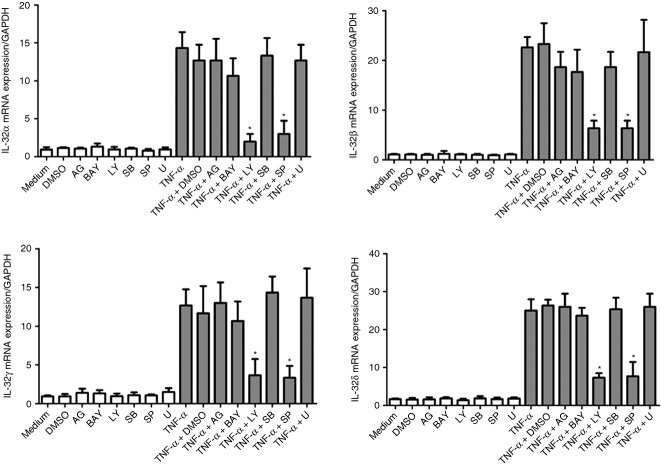

Effects of signalling molecule inhibitors on IL-32 gene expression in HLF activated by TNF-α

The levels of cytotoxic responses triggered by different signalling molecule inhibitors on HLF were first determined by the MTT assay (see Supporting information, Fig. S3), and the effective doses of these inhibitors with significant inhibitory effects on specific signalling pathways have been described in our previous studies.16,18,19 We then used the optimal concentrations of Janus kinase inhibitor AG490 (5 μm), NF-κB inhibitor BAY11-7082 (1 μm), PI3K inhibitor LY294002 (5 μm), extracellular signal-regulated kinase inhibitor U0126 (10 μm), p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 (20 μm), and JNK inhibitor SP600125 (5 μm) with significant inhibitory effects, and without any cellular toxicity. As shown in Fig.4, both LY294002 and SP600125 significantly suppressed TNF-α-induced IL-32α,β,γ and δ mRNA expression. However, other inhibitors including AG490, BAY11-7082, SB203580, and U10126 did not exert any significant effect on TNF-α-induced IL-32 mRNA expression of different isotypes in HLF.

Figure 4.

Effects of different signalling molecule inhibitors on tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) -induced interleukin-32 (IL-32) mRNA expression in human lung fibroblasts (HLF). HLF were pre-treated with AG490 (5 μm; AG), BAY11-7082 (1 μm; BAY), LY294002 (5 μm; LY), SB203580 (20 μm; LY), SP600125 (5 μm; SP), or U0126 (10 μm; U) for 1 hr, followed by incubation for a further 6 hr with or without TNF-α (30 ng/ml). The mRNA expression of IL-32 α,β,γ and δ was determined by quantitative RT-PCR. DMSO (0·1%) was used as the vehicle control. Results are expressed as the arithmetic mean ± SD from three independent experiments. *P < 0·01 when compared with HLF activated by TNF-α alone.

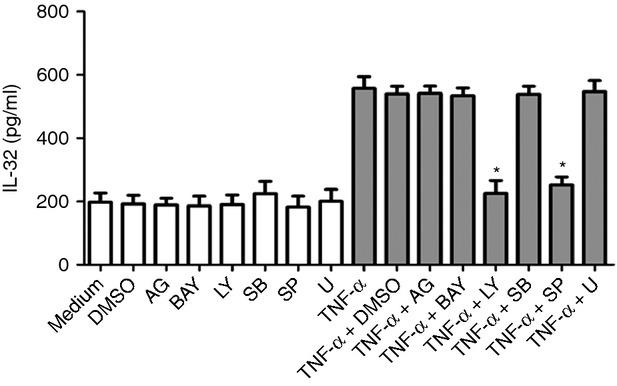

Effects of signalling molecule inhibitors on TNF-α-induced IL-32 release in HLF

As shown in Fig.5, the release of IL-32 induced by TNF-α in HLF could be significantly suppressed by LY294002 and SP600125, while AG490, BAY11-7082, SB203580 and U10126 did not affect TNF-α-induced IL-32 release in HLF. These results are therefore consistent with data from TNF-α-induced IL-32 mRNA expression in HLF.

Figure 5.

Effects of different signalling molecule inhibitors on tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) -induced interleukin-32 (IL-32) release in human lung fibroblasts (HLF). HLF were pre-treated with AG490 (5 μm; AG), BAY11-7082 (1 μm; BAY), LY294002 (5 μm; LY), SB203580 (20 μm; LY), SP600125 (5 μm; SP), or U0126 (10 μm; U) for 1 hr, followed by incubation for a further 24 hr with or without TNF-α (30 ng/ml). The release of IL-32 was determined by ELISA. DMSO (0·1%) was used as the vehicle control. Results are expressed as the arithmetic mean ± SD from three independent experiments. *P < 0·01 when compared with HLF activated by TNF-α alone.

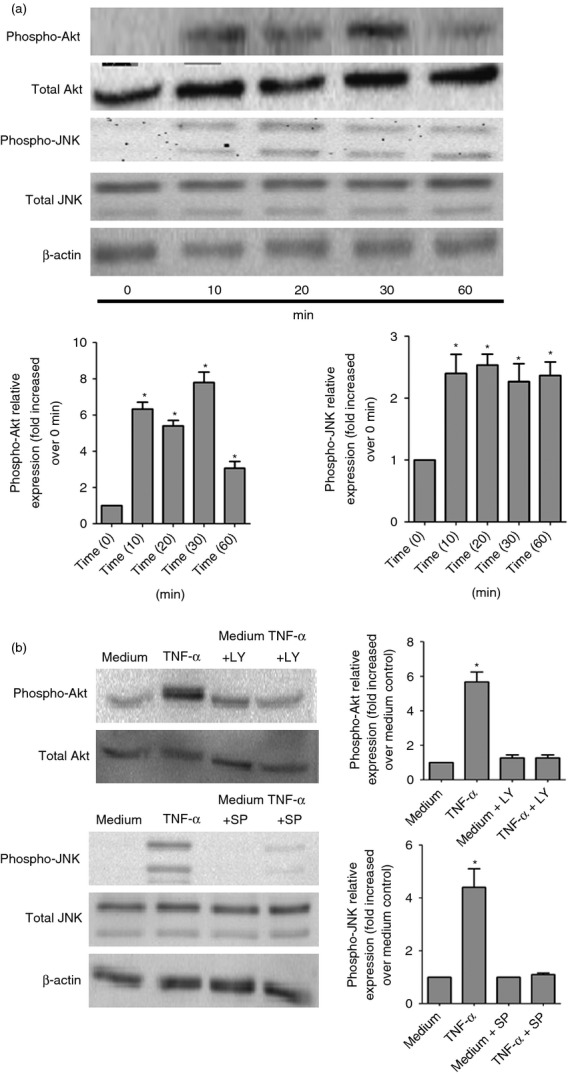

Effects of TNF-α on the activation of intracellular signalling molecules Akt and JNK in HLF

Figure6(a) shows that TNF-α could rapidly induce the phosphorylation of Akt and JNK at 10 min. Phosphorylation of Akt and JNK was detected after 30 min of TNF-α treatment and sustained to 1 hr. LY294002 and SP600125 were able to significantly suppress the phosphorylation of Akt and JNK in HLF after 30 min of TNF-α activation, respectively (Fig.6b).

Figure 6.

Effects of tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) on activation of the Akt and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) signalling pathways in human lung fibroblasts (HLF). (a) HLF (5 × 106 cells) were treated with or without TNF-α (30 ng/ml) for the indicated incubation time. Total cellular proteins were extracted for the detection of total and phosphorylated signalling proteins by Western blot analysis. Experiments were performed in three independent experiments with essentially identical results, and representative blots are shown. Densitometry quantification of blots from three experiments are as shown in histograms below. Phospho-Akt or phospho-JNK expression was normalized to β-actin for each sample, and expression was graphed as fold change above cells at 0 min. *P < 0·01 when compared with HLF activated by TNF-α at 0 min. (b) HLF were pre-treated with or without LY294002 (5 μm; LY) or SP600125 (5 μm; SP) for 1 hr, followed by incubation for a further 30 min with or without TNF-α (30 ng/ml). Total cellular proteins were extracted for the detection of total and phosphorylated signalling proteins by Western blot analysis. Medium was used as the control. Experiments were performed in three independent experiments with essentially identical results, and representative blots are shown. Densitometry quantification of blots from three experiments are as shown in histograms right. Phospho-Akt or Phospho-JNK expression was normalized to β-actin for each sample, and expression was graphed as fold change above medium control. *P < 0·01 when compared with medium control.

Discussion

Airway inflammation is a multi-cellular process involving interactions among pulmonary structural cells and other inflammatory cells, or cytokines, chemokines and growth factors.5,20 Lung fibroblasts are localized in the connective tissue as cellular communication–bridging interstitium and vasculature in the lung, and they have been recognized as playing an active role in the pathogenesis of airway inflammatory disease via the expression of inflammatory mediators.21 In this report, we demonstrated that TNF-α induced expression of IL-32 in HLF through the activation of the Akt and JNK signalling pathway, providing a novel functional linkage between two cytokines that are involved in airway inflammatory diseases.

Interleukin-32 appears to play a critical role in a variety of inflammatory diseases. An increased expression of IL-32 has been observed in lung tissue of patients with COPD, where it was co-localized with TNF-α and correlated with the degree of airflow obstruction. Interleukin-32 was also involved in the corticosteroid resistance of COPD inflammation.12 In patients with asthma, IL-32 was detectable in induced sputum and IL-32 serum levels were significantly higher in patients with asthma compared with healthy control subjects and correlated with response to asthma treatment.13 In lung adenocarcinoma, IL-32 was aberrantly over-expressed in lung adenocarcinoma tissues and cell lines, and IL-32 contributes to invasion and metastasis of primary lung adenocarcinoma via NF-κB-induced expression of matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9.22 Furthermore, there was an association between IL-32 genotypes and outcome in infection-associated acute lung injury.14 Interleukin-32 could induce the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-8 and macrophage inflammatory protein-2, and it synergized with nucleotide oligomerization domain ligands to stimulate IL-1β and IL-6 release in a caspase-1-dependent manner.23 Silencing endogenous IL-32 can impair IL-1β- or LPS-dependent production of intercellular adhesion molecule 1, TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-8 in endothelial cells.11 Endothelial/haematopoietic expression of IL-32 in transgenic mice elevated inflammation, which was associated with significant elevation of leucocyte infiltration and serum levels of TNF-α and IL-1β, increased vascular permeability and lung damage.24 A more recent report also demonstrated that IL-32 possessed angiogenic properties and IL-32 was implicated in pulmonary arterial hypertension.25 These findings therefore suggest that IL-32 contributes both to development of airway inflammation and subsequent decline in lung function. Here, we provided evidence that TNF-α is an inducer of IL-32 from HLF and is involved in pathogenesis of airway inflammatory diseases via the induction of IL-32. Elucidating interactions between TNF-α and IL-32 may be valuable in understanding and treating airway inflammatory diseases.

Interleukin-32 has been shown to be induced by TNF-α, IL-1β, IFN-γ, dsRNA and LPS in monocytes, endothelial cells, epithelial cells, keratinocytes and synoviocytes.26–29 Six isoforms of IL-32 have been reported; IL-32ε and IL-32ζ were very minor isoforms and were found only in activated T cells.30 In this study, we found that IL-32 mRNA of four spliced isoforms (α,β,γ and δ) was up-regulated in HLF upon TNF-α stimulation, which was associated with a significant IL-32 protein release from HLF. The combination of IFN-γ and TNF-α induced enhanced IL-32 release in HLF, whereas IL-4, IL-17A, IL-27 and TLR ligands did not alter IL-32 release in HLF either alone, or in combination with TNF-α. These findings are concordant with results from other groups showing that TLR2 and TLR3 ligands did not induce an increase in IL-32 release from peripheral blood mononuclear cells,26 and IL-4, IL-13 or IL-17A had no effect on IL-32 release in normal human bronchial epithelial cells or keratinocytes.27,28 However, it has been reported that fibroblast-like synoviocytes from arthritis patients produced IL-32 after TLR2 and TLR3 activation,29 while A549 human lung epithelial cells could produce IL-32 after activation with a TLR3 agonist,31 and TLR2 ligand was an inducer of IL-32 in the human THP-1 monocytic cell line, vascular endothelial cells or LCC-18 enteroendocrine cell line.11,32,33 These results indicate that IL-32 induction by TLR agonists depends on the cell type. As TNF-α has been well considered to play an important part in many pathobiological processes of airway inflammatory diseases,16,18 the involvement of TNF-α in airway inflammation is, therefore, probably mediated, in part, through the induction of IL-32 from HLF. In another study, it has been demonstrated that blocking of the TNF-receptor, TNFR1, could suppress IL-32-induced downstream responses.34 Therefore, the TNF-α/IL-32 axis in HLF should provide new insights into the molecular mechanisms involved in airway inflammation and lung function decline.

Our former studies have shown that PI3K-Akt, p38 MAPK, or NF-κB signalling pathways played crucial roles in TNF-α-mediated release of cytokines, chemokines and expression of adhesion molecules in pulmonary epithelial cells and fibroblasts.16,18 In this study, we have found that the activation of Akt and JNK pathways regulated TNF-α-induced IL-32 expression in HLF, and inhibition of Akt and JNK pathways could suppress the increased release of IL-32 to nearly the basal level. Although the JNK signalling pathway has been suggested to regulate IL-32 production in cytokine-activated synoviocytes,35 a novel finding of our study is that IL-32 expression was regulated by the PI3K/Akt pathway in TNF-α-stimulated HLF. In addition, human airway epithelial cells (BEAS-2B) infected with Mycobacterium avium produced IL-32, which was dependent on NF-κB but independent of p38 and extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathways,36 while inhibition of NF-κB did not alter IL-32 production from HLF by TNF-α in our study. The above discrepancy suggests that different signalling pathways selectively regulate IL-32 production in a stimulator-specific manner or in a cell type-dependent way. Further studies are also required to investigate the cross-talk between PI3K/Akt and JNK signalling pathways, which mediates the release of IL-32 in activated HLF by TNF-α.

It has been reported that TNF-α levels are up-regulated in patients with COPD or asthma,16,37 and the levels of IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-17 and IL-27 were also increased in these patients.38–41 Although the precise concentrations of TNF-α and other cytokines are unknown in the lung microenvironment during COPD or asthma, it is postulated that cytokine concentration should be significantly higher in local inflammatory sites than in circulation. Moreover, our recombinant cytokine concentrations used in the present study were only 0–100 ng/ml, which are similar to previous concentrations used in studies in vitro.16,18,19,11,35,42 Therefore, it is physiological that TNF-α might activate HLF to produce IL-32 at sites of inflammation.

In conclusion, the present report is the first demonstration of TNF-α-induced IL-32 expression in HLF via the Akt and JNK signalling pathways. The individual role of TNF-α and IL-32 in airway inflammatory diseases has been suggested, and our study provides new evidence for a functional linkage between these two cytokines in HLF, further strengthening their involvement in airway inflammation. In view of the recent development of cytokine inhibitors as potential anti-inflammatory agents,5 our study has potential implications in the development of therapeutic interventions for airway inflammatory diseases.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation Grants of China (No. 81370110) and Natural Science Foundation Project of Chongqing (No. CSTC 2011jjA10063).

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Dose-dependent release of interleukin-32 from human lung fibroblasts activated by different cytokines.

Figure S2 Dose-dependent release of interleukin-32 from human lung fibroblasts activated by different Toll-like receptor ligands.

Effects of signalling molecule inhibitors on the viability of human lung fibroblasts (HLF). HLF (2 × 104/0·2 ml) were incubated with serial concentrations of AG490, BAY11-7082, LY294002, SB203580, SP600125, U0126 or DMSO for 48 hr, and the cell viability was assessed by MTT test.

References

- Hallstrand TS, Hackett TL, Altemeier WA, Matute-Bello G, Hansbro PM, Knight DA. Airway epithelial regulation of pulmonary immune homeostasis and inflammation. Clin Immunol. 2014;151:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grainge CL, Davies DE. Epithelial injury and repair in airways diseases. Chest. 2013;144:1906–12. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-1944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brusselle GG, Provoost S, Bracke KR, Kuchmiy A, Lamkanfi M. Inflammasomes in respiratory disease: from bench to bedside. Chest. 2014;145:1121–33. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezaee F, Georas SN. Breaking barriers. New insights into airway epithelial barrier function in health and disease. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2014;50:857–69. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2013-0541RT. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuijs MJ, Willart MA, Hammad H, Lambrecht BN. Cytokine targets in airway inflammation. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2013;13:351–61. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2013.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koltsida O, Karamnov S, Pyrillou K. Toll-like receptor 7 stimulates production of specialized pro-resolving lipid mediators and promotes resolution of airway inflammation. EMBO Mol Med. 2013;5:762–75. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201201891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazzan E, Saetta M, Turato G. Expression of the atypical chemokine receptor D6 in human alveolar macrophages in COPD. Chest. 2013;143:98–106. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-3220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joosten LA, Heinhuis B, Netea MG, Dinarello CA. Novel insights into the biology of interleukin-32. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013;70:3883–92. doi: 10.1007/s00018-013-1301-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Sun W, Liu L. IL-32: a host proinflammatory factor against influenza viral replication is upregulated by aberrant epigenetic modifications during influenza A virus infection. J Immunol. 2010;185:5056–65. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Kim JH, Kim H. Activation of the interleukin-32 pro-inflammatory pathway in response to human papillomavirus infection and over-expression of interleukin-32 controls the expression of the human papillomavirus oncogene. Immunology. 2011;132:410–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2010.03377.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nold-Petry CA, Nold MF, Zepp JA, Kim SH, Voelkel NF, Dinarello CA. IL-32-dependent effects of IL-1β on endothelial cell functions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:3883–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813334106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese F, Baraldo S, Bazzan E. IL-32, a novel proinflammatory cytokine in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:894–901. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200804-646OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer N, Christoph J, Makrinioti H. Inhibition of angiogenesis by IL-32: possible role in asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:964–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.12.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arcaroli JJ, Liu N, Yi N, Abraham E. Association between IL-32 genotypes and outcome in infection-associated acute lung injury. Crit Care. 2011;15:R138. doi: 10.1186/cc10258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreymueller D, Martin C, Kogel T, Pruessmeyer J, Hess FM, Horiuchi K, Uhlig S, Ludwig A. Lung endothelial ADAM17 regulates the acute inflammatory response to lipopolysaccharide. EMBO Mol Med. 2012;4:412–23. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201200217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong S, Zhang X, He Y. Synergy of IL-27 and TNF-α in regulating CXCL10 expression in lung fibroblasts. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2013;48:518–30. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0340OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bang BR, Kwon HS, Kim SH. Interleukin-32γ suppresses allergic airway inflammation in mouse models of asthma. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2014;50:1021–30. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2013-0234OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao J, Wong CK, Yin Y, Lam CW. Activation of human bronchial epithelial cells by inflammatory cytokines IL-27 and TNF-α: implications for immunopathophysiology of airway inflammation. J Cell Physiol. 2010;223:788–97. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao J, Zhang L, Li D, Xu F, Huang S, Xiang Y, Yin Y, Ren G. IL-27 is elevated in patients with COPD and patients with pulmonary TB and induces human bronchial epithelial cells to produce CXCL10. Chest. 2012;141:121–30. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-3297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarze J, Mackenzie KJ. Novel insights into immune and inflammatory responses to respiratory viruses. Thorax. 2013;68:108–10. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews AL, Nasir T, Bucchieri F, Holloway JW, Holgate ST, Davies DE. IL-13 receptor α2: a regulator of IL-13 and IL-4 signal transduction in primary human fibroblasts. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118:858–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Q, Li S, Zhou Y. Interleukin-32 contributes to invasion and metastasis of primary lung adenocarcinoma via NF-κB induced matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9 expression. Cytokine. 2014;65:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2013.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netea MG, Azam T, Ferwerda G. IL-32 synergizes with nucleotide oligomerization domain (NOD) 1 and NOD2 ligands for IL-1β and IL-6 production through a caspase 1-dependent mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:16309–14. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508237102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi H, Huang J, Ye F, Shyr Y, Blackwell TS, Lin PC. Interleukin-32β propagates vascular inflammation and exacerbates sepsis in a mouse model. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9458. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nold-Petry CA, Rudloff I, Baumer Y. IL-32 promotes angiogenesis. J Immunol. 2014;192:589–602. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netea MG, Azam T, Lewis EC. Mycobacterium tuberculosis induces interleukin-32 production through a caspase- 1/IL-18/interferon-γ-dependent mechanism. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e277. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keswani A, Chustz RT, Suh L. Differential expression of interleukin-32 in chronic rhinosinusitis with and without nasal polyps. Allergy. 2012;67:25–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02706.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer N, Zimmermann M, Bürgler S. IL-32 is expressed by human primary keratinocytes and modulates keratinocyte apoptosis in atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:858–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsaleh G, Sparsa L, Chatelus E, Ehlinger M, Gottenberg JE, Wachsmann D, Sibilia J. Innate immunity triggers IL-32 expression by fibroblast-like synoviocytes in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:R135. doi: 10.1186/ar3073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goda C1, Kanaji T, Kanaji S, Tanaka G, Arima K, Ohno S, Izuhara K. Involvement of IL-32 in activation-induced cell death in T cells. Int Immunol. 2006;18:233–40. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Yang F, Liu Y. Negative feedback regulation of IL-32 production by iNOS activation in response to dsRNA or influenza virus infection. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:1019–24. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama M, Niki Y, Kawasaki T, Takeda Y, Ikegami H, Toyama Y, Miyamoto T. IL-32-PAR2 axis is an innate immunity sensor providing alternative signaling for LPS-TRIF axis. Sci Rep. 2013;3:2960. doi: 10.1038/srep02960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selleri S, Palazzo M, Deola S, Wang E, Balsari A, Marincola FM, Rumio C. Induction of pro-inflammatory programs in enteroendocrine cells by the Toll-like receptor agonists flagellin and bacterial LPS. Int Immunol. 2008;20:961–70. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxn055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner-Brannen E, Choi KY, Arsenault R, El-Gabalawy H, Napper S, Mookherjee N. Inflammatory cytokines IL-32 and IL-17 have common signaling intermediates despite differential dependence on TNF-receptor 1. J Immunol. 2011;186:7127–35. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mun SH, Kim JW, Nah SS. Tumor necrosis factor α-induced interleukin-32 is positively regulated via the Syk/protein kinase Cδ/JNK pathway in rheumatoid synovial fibroblasts. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:678–85. doi: 10.1002/art.24299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai X, Ovrutsky AR, Kartalija M. IL-32 expression in the airway epithelial cells of patients with Mycobacterium avium complex lung disease. Int Immunol. 2011;23:679–91. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxr075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soler N, Ewig S, Torres A, Filella X, Gonzalez J, Zaubet A. Airway inflammation and bronchial microbial patterns in patients with stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 1999;14:1015–22. doi: 10.1183/09031936.99.14510159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong CK, Ho CY, Ko FW, Chan CH, Ho AS, Hui DS, Lam CW. Proinflammatory cytokines (IL-17, IL-6, IL-18 and IL-12) and Th cytokines (IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-10 and IL-13) in patients with allergic asthma. Clin Exp Immunol. 2001;125:177–83. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2001.01602.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon J, Ernst P, Yamauchi Y. Differences in airway cytokine profile in severe asthma compared to moderate asthma. Chest. 2008;133:420–6. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barceló B, Pons J, Fuster A, Sauleda J, Noguera A, Ferrer JM, Agustí AG. Intracellular cytokine profile of T lymphocytes in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 2006;145:474–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03167.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eustace A1, Smyth LJ, Mitchell L, Williamson K, Plumb J, Singh D. Identification of cells expressing IL-17A and IL-17F in the lungs of patients with COPD. Chest. 2011;139:1089–100. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi M, Kokubu F, Kuga H. Modulation of bronchial epithelial cells by IL-17. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108:804–9. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.119027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Dose-dependent release of interleukin-32 from human lung fibroblasts activated by different cytokines.

Figure S2 Dose-dependent release of interleukin-32 from human lung fibroblasts activated by different Toll-like receptor ligands.

Effects of signalling molecule inhibitors on the viability of human lung fibroblasts (HLF). HLF (2 × 104/0·2 ml) were incubated with serial concentrations of AG490, BAY11-7082, LY294002, SB203580, SP600125, U0126 or DMSO for 48 hr, and the cell viability was assessed by MTT test.