Abstract

Fas Ligand limits inflammatory injury and permits allograft survival by inducing apoptosis of Fas-bearing lymphocytes. Previous studies have shown that the CD4+ T-cell is both sufficient and required for murine cardiac allograft rejection. Here, utilizing a transgenic mouse that over-expresses Fas Ligand specifically on cardiomyocytes as heart donors, we sought to determine if Fas Ligand on graft parenchymal cells could resist CD4+ T-cell mediated rejection. When transplanted into fully immunocompetent BALB/c recipients Fas Ligand transgenic hearts were acutely rejected. However, when transplanted into CD4+ T-cell reconstituted BALB/c-rag-/- recipients, Fas Ligand hearts demonstrated long-term survival. These results indicate that Fas Ligand over-expression on cardiomyocytes can indeed resist CD4+ T-cell mediated cardiac rejection and suggests contact dependence between Fas Ligand expressing graft parenchymal cells and the effector CD4+ T-cells.

Keywords: Rejection, fas ligand, transplantation

1. Introduction

The primary mode of resolution for many end-stage organ failures is transplantation of the diseased organ with a healthy organ. This requires an often life long dependence on nonspecific immunosuppression. Although all the mechanisms of allograft rejection have yet to be defined, it is known that CD4+ T-cells are critical for cardiac allograft immunity [1-8]. Previous studies in our laboratory have revealed that CD4+ T-cells are both sufficient and required for allograft rejection and that direct presentation of donor antigen is required for the activation of CD4+ T-cells [1]. We have also shown that donor expression of Fas is required for FasL1 expressing T-cell destruction to occur in the context of perforin expressing CD4+ T-cells [9]. Zuraff-Perryman et al [10] transplanted isolated cardiomyocytes expressing FasL under the kidney capsule of CD8+ T-cell deficient allogeneic recipients and demonstrated resistance to CD4+ T-cell mediated rejection. Further, it has been shown that CD4+ T-cells are sensitive to contact dependent apoptosis via Fas/FasL interactions [11]. As a progression of the previous findings utilizing our mouse model of direct CD4+ T-cell dependent rejection of cardiac allografts we sought to determine if rejection could be delayed by over-expression of FasL on the allograft as a potential means to inhibit CD4+ T-cells via presumed allograft FasL:CD4+ T-cell Fas interaction.

Fas ligand (FasL, CD95L) is a cell surface molecule in the tumor necrosis factor superfamily. FasL induces apoptotic cell death of Fas-bearing cells by binding to the membrane receptor Fas (CD95, APO1) [12]. Interactions between Fas and FasL are integral to several immune processes including regulation of lymphocyte homeostasis, T-cell-mediated cytotoxicity and immune privilege [12, 13]. Activated T-cells up-regulate expression of Fas rendering them susceptible to activation-induced cell death by engagement with FasL [14]. This Fas-FasL apoptosis can lead to antigen-specific down regulation of immune responses and is also a key mechanism for the protection of immune privileged sites such as eyes [13], the placenta [15] and testes [16]. Forced or ectopic expression of FasL, thereby engineering immune privileged tissues, has been considered as a strategy for immune protection of allografts from active cellular rejection in the past [17]. Whereas in our previous study we found that Fas expression on the donor parenchymal cells was required for graft destruction by CD4+ T-cells, we posited that Fas expression on those same alloreactive CD4+ T-cells might be utilized to kill those T-cells if they were to be bound by FasL on the graft parenchyma. To explore this notion a transgenic mouse was generated that over-expresses FasL under the αMHC promoter on cardiomyocytes [18] to potentially modulate a CD4+ T-cell mediated response in a fully vascularized, whole organ transplant model.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Mice

Inbred female FVB/n (H-2q), BALB/cByJ (BALB/c, H-2d) and BALB/c-rag-/- (H-2 d) mice, were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). C.B-2-+17scid/scid (H-2 d) mice were purchased from Taconic Farms (Germantown, NY). (NB: between the time this study was commenced and completed, BALB/c rag-/- mice replaced C.B-17 scid mice as our standard immunodeficient recipient. Importantly, both animals are H-2d.) Fas ligand over-expressing mice (H-2q) were generously provided by Dr. Nelson, Cincinnati Children's Hospital (Cincinnati, OH) [18]. Animals were housed under pathogen free conditions at the University of Colorado, Barbara Davis Center Animal Facility according to NIH Guidelines and with approval of the University of Colorado Denver IACUC.

2.2 Heterotopic Cardiac Transplantation

Cardiac allografts were performed according to standard microsurgical techniques [19, 20]. The donor heart was placed in 4°C saline until transplantation, end to side anastomosis of the donor aorta to the recipient aorta and end to side anastomosis of the donor pulmonary artery to the recipient IVC were made using 10-0 nylon suture. Graft survival was monitored by palpation with rejection defined as cessation of detectable beat and confirmed by laparotomy under anesthesia.

2.3 CD4+ T-Cell Purification and Adoptive Transfer

Single cell suspension of lymphocytes from BALB/c mice were prepared from lymph nodes according to standard procedures [1, 9]. 10×106 CD4+ enriched T-cells (CD4-enriched T-cells contained <0.5% contaminating CD8+ T-cells or CD19+ B-cells, confirmed by flow cytometry) were injected I.P. into the adoptive transfer recipients on day 3-5 relative to cardiac transplant. This number of transferred cells reflects those used in our previous studies [1, 21] and was used to remain consistent with those studies.

2.4 Histology

Transplanted and native hearts were removed and divided in half in the long axis perpendicular to the intraventricular septum. Halves were then placed in 10% formaldehyde. Sections were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and examined in a blinded fashion.

2.5 Statistical Analysis

Kaplan-Meier test using commercially available software, was used to determine significance of graft survival data.

3. Results

3.1 Control FVB donor hearts are robustly rejected in both allogeneic wild type recipients and immunodeficient recipients reconstituted with CD4+ T-cells

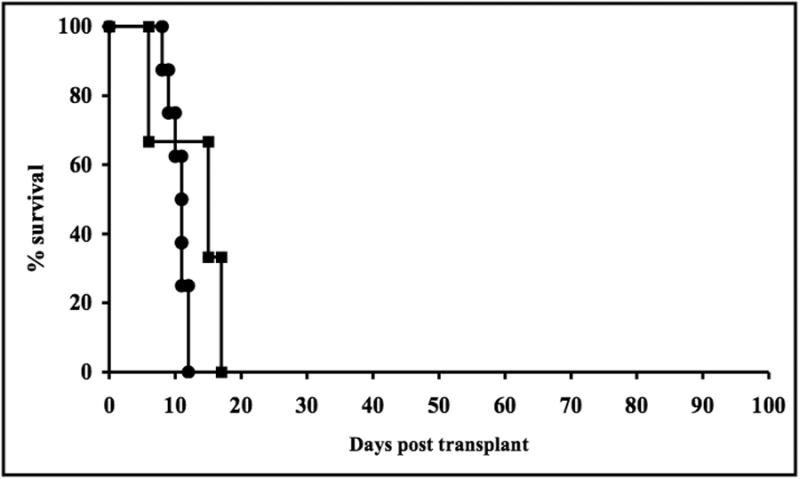

Because all the FasL over-expressing mice in this study were derived on a FVB background, hearts from control FVB donors were transplanted into BALB/c recipients and were acutely rejected (10.3 +/- 1.3 days). FVB donor hearts transplanted into immunodeficient C.B-17 scid recipients that were reconstituted with purified BALB/c CD4+ T-cells were rejected with almost identical kinetics (10.7 +/- 1.5 days, p=NS) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. FVB control cardiac allografts and FasL cardiac allografts are acutely rejected.

FVB (●) and FasL (■) cardiac allografts are rejected in very similar tempo when transplanted into BALB/c (H-2d) wild type recipients.

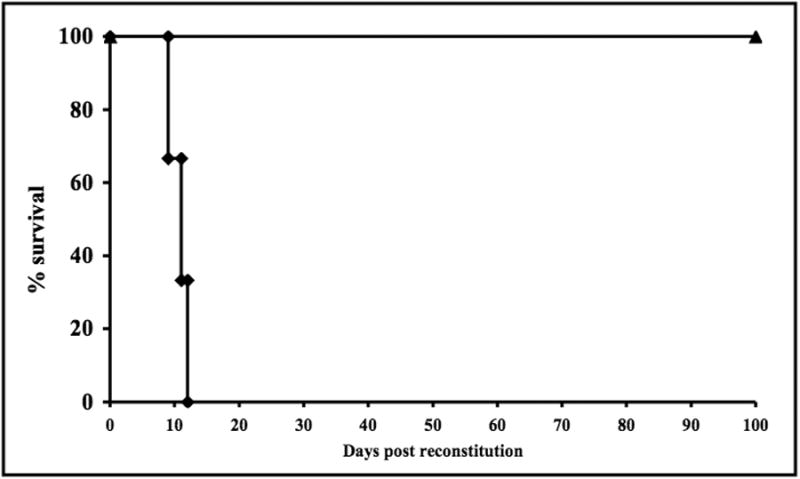

3.2 FasL over-expressing cardiac allografts survive long term in BALB/c-rag-/- recipients reconstituted with BALB/c CD4+ T-cells

FasL over-expressing donor hearts were rejected by fully immune competent wild-type BALB/c hosts in similar kinetics to FVB donors, (12.7 +/- 5.9 days). However, when FasL hearts were transplanted into BALB/c-rag-/- recipients that were reconstituted with BALB/c CD4+ T-cells, the grafts survived long term (>100 days, p=0.01) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. FasL over-expressing cardiac allografts survive indefinitely in BALB/c-rag-/-recipients reconstituted with BALB/c CD4+ T-cells.

Donor hearts from FasL mice survived indefinitely in BALB/c-rag-/- mice that had been reconstituted with purified CD4+ T-cells (▲) while FVB hearts were rejected in CD4+ T-cell reconstituted C.B-17 scid (H-2d) recipients (◆).

3.3 FasL over-expressing cardiac allografts do not contain graft destructive cells

Acutely rejected cardiac allografts display extensive mononuclear cell infiltration and evidence of necrosis and hemorrhage (Fig. 3a). In contrast, long-term surviving FasL hearts transplanted into BALB/c-rag-/- recipients that have been reconstituted with BALB/c CD4+ T-cells demonstrate graft infiltrating mononuclear cells in the ventricular endocardium, but a paucity of infiltrating cells in the myocardium (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3. a and b FasL over-expressing cardiac allografts do not contain graft destructive cells.

a. Histology of a graft that has been acutely rejected displays extensive mononuclear cell infiltration and evidence of necrosis and hemorrhage. b. A long-term surviving FasL heart in a CD4+ T-cell reconstituted BALB/c-rag-/- recipient demonstrating graft infiltrating mononuclear cells in the ventricular endocardium, but a paucity of infiltrating cells in the myocardium.

4. Discussion

The host allo-rejection response is protean in the individual mechanisms used to destroy a solid organ transplant. It is not surprising that FasL over-expression has not been able to completely protect allografts from all these simultaneous mechanisms in the fully immune competent host. Due to continuing controversy and conflicting and confounding reports, the potential for FasL as an immuno-modulator in the context of transplant immunity continues to be investigated. The literature includes paradoxical and conflicting results as studies have attempted to harness the potential of these immune mediators for either tumor or transplantation immunology [17, 22]. Initial hypotheses that these molecules could bestow immune privilege to the tissues that expressed them led to a number of studies which attributed tumor survival or allograft survival to the forced expression of FasL on the cell surface [23-26]. Others have even reported tolerance induction [27-29]. To confound the field there have been studies which showed either lack of graft prolongation or even accelerated rejection [30, 32]. Those studies however must be viewed in context; Jekle et al utilized a specific antigen presenting cell transfected with FasL in an in vitro model and found intact T-cell cytotoxity. Kang et al expressed FasL on islets of Langerhans, a cellular transplant rather than a solid organ model, and found rapid destruction of the islets. And Takeuchi used a different FasL construct protocol and different mouse strain combinations compared to this current study. Importantly, he also did not look specifically at an isolated CD4+ T-cell model. The field has now come to recognize that forced expression of FasL can also cause pro-inflammatory consequences [18]. The presence of this pro-inflammatory effect does not preclude the possibility that cardiac FasL expression may be immune protective, as demonstrated here.

Fas/FasL are important molecules in immune regulation and in context may have both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory effects. We describe experiments in which the forced expression of FasL on solid organ graft parenchymal cells does not result in accelerated graft loss, yet is insufficient for graft survival in immune competent animals with a full complement of T and B-cells. Importantly, our results demonstrate complete abrogation of cardiac allograft rejection when isolated to the critical CD4+ T-cell mediated effector response alone.

Previously we have determined that the required cell for mediating acute CD4+ T-cell mediated cardiac rejection in the mouse is a directly cytotoxic, Th1 type, CD4+ T-cell which relies on Fas/perforin in parallel for effector function [9]. Therefore it is highly likely that in this current model system it is that cytotoxic CD4+ T-cell population that is undergoing Fas:FasL mediated cell death. Nonetheless, it is important to note that other CD4+ T-cell populations express Fas [33] and therefore in theory could also be susceptible to FasL-mediated killing by FasL over-expressing cardiomyocytes. However, it is unclear if these other sub-populations of CD4+ T-cells (i.e. Th17, T-regs) engage the graft in a cognate fashion (direct contact) – such that Fas:FasL interaction could occur and lead to T-cell death under these experimental conditions. Importantly, as stated above, previous studies from our group do demonstrate a requirement for cognate interaction by cytotoxic (Th1) effector CD4 T-cells in acute murine CD4+ T-cell mediated cardiac rejection (9) and therefore are likely the cells undergoing deletion via FasL on cardiomyocytes in the current study.

A somewhat perplexing yet interesting finding in this study is the observation that FasL over-expressing cardiac allografts are rejected in wild type (Wt) hosts yet survive indefinitely in Rag-/- hosts reconstituted with purified host-type CD4+ T-cells. A postulated potential mechanism by which allograft rejection is prevented in CD4+ T-cell isolated cardiac alloimmunity is killing of Fas expressing CD4+ effector T-cells by FasL over-expressing cardiomyocytes. However, a potential problem with that explanation is the fact that cardiac allograft rejection is CD4+ T-cell dependent [1-8], yet Wt recipients (containing a full immune repertoire of cells, including CD4+ T-cells) still reject FasL over-expressing grafts. This result may suggest a mechanism other than cardiomyocyte FasL-directed killing of Fas expressing CD4+ T-cells, however other potential explanations exist. Additionally, differential CD4+ T-cell reactivity under Wt and lymphopenic Rag-/- host conditions may be at play. However, given that the homeostatic expansion of T-cells seen after transfer to lymphopenic Rag-/- recipients should in theory increase T-cell reactivity (via incidental activation during expansion), one would expect that the Rag-/- recipient mice be more capable of rejecting FasL over-expressing allografts – yet we see the opposite result. Although the CD4+ T-cell is required for cardiac allograft rejection [1-8], a directly reactive CD4+ T-cell (donor MHC-restricted) has only been demonstrated to be required specifically for isolated CD4+ T-cell mediated acute cardiac rejection [9]. In fact, MHC II-/- allografts are not rejected in Wt hosts [1] – demonstrating that under Wt conditions indirectly reactive CD4+ T-cells (host MHC-restricted) are important. Unlike direct CD4+ T-cells – these ‘indirect’ cells likely do not require cell-cell contact with the graft for effector/helper function and therefore may not be susceptible to FasL-directed killing by cardiomyocytes.

We find that although not all mechanisms of allograft rejection are attenuated by allograft FasL expression, acute CD4+ T-cell mediated cardiac allograft rejection is markedly attenuated. This result is important as it functions to support previous findings demonstrating a requirement for a directly cytotoxic CD4+ T-cell in acute CD4+ T-cell mediated murine cardiac rejection and importantly points toward a new potential therapeutic target to add to the current “therapeutic arsenal” in clinical cardiac transplantation.

5. Conclusion

Our results indicate that FasL over-expression on cardiomyocytes can resist CD4+ T-cell-mediated cardiac rejection, but does not prevent rejection in the intact wild-type host.

Highlights.

We over-expressed Fas ligand on donor cardiomyocytes

We investigated if this ectopic expression could prolong cardiac graft survival

FasL was incapable of prolonging grafts in fully immunocompetent recipients

FasL was capable of prolonging grafts when exposed to CD4+ T-cells

Acknowledgments

Funding. This work was supported by NIH Grants R01 HL64976-02 (BAP) and RO1 DK 45773 (RGG) and DERC P30 DK57516.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: FasL, Fas ligand; Tg, transgenic

Authors contributions and declaration: R.P. and B.P. performed the transplants.

R.P., T.G. and B.P. collected the data.

B.P., D.N. and R.G. participated in making the research design.

D.N. provided the FasL mouse.

R.P. and T.G. performed the statistical analysis of the data.

R.P., T.G., M.Z., R.G. and B.P. participated in analyzing the data and writing the paper.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Todd J. Grazia, Email: Todd.Grazia@ucdenver.edu.

David P. Nelson, Email: David.Nelson@cchmc.org.

Martin R. Zamora, Email: Marty.Zamora@ucdenver.edu.

Ronald G. Gill, Email: Ronald.Gill@ucdenver.edu.

Biagio A. Pietra, Email: Bill.Pietra@ucdenver.edu.

References

- 1.Pietra BA, Wiseman A, Bolwerk A, Rizeq M, Gill RG. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:1003–10. doi: 10.1172/JCI10467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herbert J, Roser B. Transplantation. 1988;46:128S–134S. doi: 10.1097/00007890-198808001-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shizuru JA, Seydel KB, Flavin TF, Wu AP, Kong CC, Hoyt EG, Fujimoto N, Billingham ME, Starnes VA, Fathman CG. Transplantation. 1990;50:366–73. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199009000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pearson TC, Madsen JC, Larsen CP, Morris PJ, Wood KJ. Transplantation. 1992;54:475–83. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199209000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pearson TC, Hamano K, Morris PJ, Wood KJ. Transplant Proc. 1993;25:786–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yin D, Fathman CG. J Immunol. 1995;154:6339–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Onodera K, Lehmann M, Akalin E, Volk HD, Sayegh MH, Kupiec-Weglinski JW. J Immunol. 1996;157:1944–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Orosz CG, Wakely E, Bergese SD, VanBuskirk AM, Ferguson RM, Mullet D, Apseloff G, Gerber N. Transplantation. 1996;61:783–91. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199603150-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grazia TJ, Plenter RJ, Weber SM, Lepper HM, Victorino F, Zamora MR, Pietra BA, Gill RG. Transplantation. 2010;89:33–9. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181be6bc7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zuraff-Perryman LA, Duke RC, Setser E, Nelson DP, Bellgrau D. Transplant Proc. 2002;34:3396–8. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(02)03621-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramaswamy M, Cruz AC, Cleland SY, Deng M, Price S, Rao VK, Siegel RM. Cell Death Differ. 2011;18:712–20. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alderson MR, Tough TW, Davis-Smith T, Braddy S, Falk B, Schooley KA, Goodwin RG, Smith CA, Ramsdell F, Lynch DH. J Exp Med. 1995;181:71–7. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Griffith TS, Brunner T, Fletcher SM, Green DR, Ferguson TA. Science. 1995;270:1189–92. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5239.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramsdell F, Seaman MS, Miller RE, Picha KS, Kennedy MK, Lynch DH. Int Immunol. 1994;6:1545–53. doi: 10.1093/intimm/6.10.1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xerri L, Devilard E, Hassoun J, Mawas C, Birg F. Mol Pathol. 1997;50:87–91. doi: 10.1136/mp.50.2.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bellgrau D, Gold D, Selawry H, Moore J, Franzusoff A, Duke RC. Nature. 1995;377:630–2. doi: 10.1038/377630a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lau HT, Yu M, Fontana A, Stoeckert CJ., Jr Science. 1996;273:109–12. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5271.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nelson DP, Setser E, Hall DG, Schwartz SM, Hewitt T, Klevitsky R, Osinska H, Bellgrau D, Duke RC, Robbins J. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1199–208. doi: 10.1172/JCI8212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Corry RJ, Winn HJ, Russell PS. Transplantation. 1973;16:343–50. doi: 10.1097/00007890-197310000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Plenter RJ, Zamora MR, Grazia TJ. J Invest Surg. 2013;26:223–8. doi: 10.3109/08941939.2012.755238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wiseman AC, Pietra BA, Kelly BP, Rayat GR, Rizeq M, Gill RG. J Immunol. 2001;167:5457–63. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.9.5457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kang SM, Hoffmann A, Le D, Springer ML, Stock PG, Blau HM. Science. 1997;278:1322–4. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5341.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duke RC, Newell E, Schleicher M, Meech S, Bellgrau D. Transplant Proc. 1999;31:1479–81. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(99)00012-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Askenasy N, Yolcu ES, Wang Z, Shirwan H. Circulation. 2003;107:1525–31. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000064893.96179.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feng YG, Jin YZ, Zhang QY, Hao J, Wang GM, Xie SS. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:2379–81. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kawamoto K, Tanemura M, Ito T, Deguchi T, Machida T, Nishida T, Doki Y, Mori M, Sawa Y. Xenotransplantation. 2008;15:333–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2008.00490.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yolcu ES, Zhao H, Bandura-Morgan L, Lacelle C, Woodward KB, Askenasy N, Shirwan H. J Immunol. 2011;187:5901–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yolcu ES, Gu X, Lacelle C, Zhao H, Bandura-Morgan L, Askenasy N, Shirwan H. J Immunol. 2008;181:931–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.2.931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dresske B, Lin X, Huang DS, Zhou X, Fandrich F. Hum Immunol. 2002;63:853–61. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(02)00448-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jekle A, Obst R, Lang F, Rammensee HG, Gulbins E. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;272:395–9. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kang SM, Schneider DB, Lin Z, Hanahan D, Dichek DA, Stock PG, Baekkeskov S. Nat Med. 1997;3:738–43. doi: 10.1038/nm0797-738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takeuchi T, Ueki T, Nishimatsu H, Kajiwara T, Ishida T, Jishage K, Ueda O, Suzuki H, Li B, Moriyama N, Kitamura T. J Immunol. 1999;162:518–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fang Y, Yu S, Ellis JS, Sharav T, Braley-Mullen H. J Leukoc Biol. 2010;87:1019–28. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0509352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]