Abstract

Molecular identification and in vitro antifungal susceptibility tests of 43 Aspergillus section Nigri isolates from China were performed. Aspergillus niger and Aspergillus tubingensis were present in almost equal numbers. All of the isolates had low MIC/MECs (minimum effective concentrations) for the 7 common antifungals, and a paradoxical effect was observed for the first time in response to caspofungin and micafungin.

TEXT

Aspergillus section Nigri, which includes 26 species of black Aspergillus, is important in medical mycology, food science, and biotechnology (1). More importantly, in the clinical setting, Aspergillus niger, which is the most commonly described species of Aspergillus section Nigri, is the third most common pathogen that causes invasive pulmonary aspergillosis and the most frequent etiological agent of otomycosis (2, 3). However, Aspergillus section Nigri is one of the most difficult groups to classify; species that belong to this group are typically identified as A. niger based on morphological observations in the clinical laboratory (4). In recent years, sequence-based molecular methods have been used successfully for species identification in this group, particularly methods using the calmodulin gene, which can distinguish all species within section Nigri (4–6). Molecular studies indicated that several species in addition to A. niger were able to cause human infections; different regions had different species of pathogenic black Aspergillus, and A. niger and Aspergillus tubingensis were the most frequently identified pathogens in previous studies (2, 7–14). Additionally, it is worth noting in a clinical context that azoles exhibited different activity against the two species and that isolates from different geographical regions exhibited remarkable differences in susceptibility to azoles and amphotericin B (1–13, 15). In light of this situation, accurate identification and susceptibility testing are necessary in the clinic.

To date, no reports are available concerning the identification and antifungal susceptibility testing of black Aspergillus in China. The aim of this study was to reidentify black Aspergillus isolates from Chinese clinical patients and environments based on sequence analysis of the calmodulin gene. Furthermore, in vitro drug susceptibility was tested to evaluate the same isolates.

A total of 43 isolates that belong to Aspergillus section Nigri and had been preidentified as A. niger based on morphology were collected nationally by the Research Center for Medical Mycology at Peking University between 1997 and 2014. These isolates included 27 from clinical samples and 16 from the environment. For details, see Table S1 in the supplemental material. Isolates were cultured on 2% malt extract agar (MEA) at 28°C for 5 days and were subsequently investigated using molecular analysis and antifungal susceptibility tests.

Genomic DNA was extracted and purified according to the instructions provided with the DNeasy plant minikit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), with modifications: the cells were disrupted using glass beads (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA) and the TissueLyser II system (Qiagen). The fungal isolates were identified via PCR amplification and sequencing of the partial calmodulin gene and the partial beta-tubulin gene when necessary using the CL1 and CL2A primer pair (16) and the Bt2a and Bt2b primer pair (17), respectively; the sequence data were adjusted using SeqMan Pro software (DNAStar, Madison, WI, USA); then they were used to conduct alignment analysis for preliminary species identification in the NCBI genomic database (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and CBS database (http://www.cbs.knaw.nl/Collections/BioloMICSSequences.aspx?file=all).

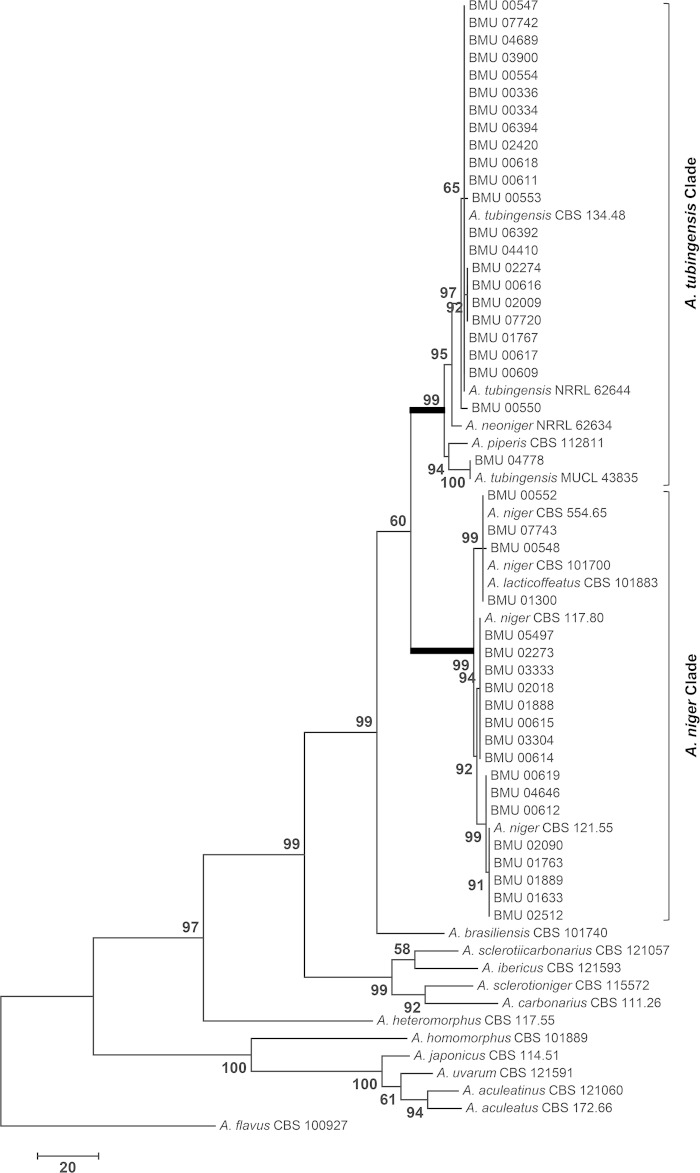

Additional GenBank sequences for Aspergillus section Nigri calmodulin and beta-tubulin genes were subsequently incorporated for comparison and reference. Phylogenetic trees were prepared from alignments using the MEGA 6.06 program (18–20). The maximum-parsimony tree was obtained using the Tree-Bisection-Regrafting (TBR) algorithm with search level 2, in which the initial trees were obtained via the random addition of sequences (10 replicates). The support for each clade was determined using bootstrap analysis with 1,000 replications. Aspergillus flavus CBS 100927 was used as an outgroup in this analysis. All sequences from our isolates were deposited in the NCBI GenBank database.

In vitro susceptibility testing was performed in triplicate based on CLSI document M38-A2 (21). The final concentration of spores dispensed into the wells was adjusted to approximately 1.5 × 104 CFU/ml, as determined by quantitative spore counting using a hemocytometer. All antifungal drugs were obtained as standard powders. The final concentrations of amphotericin B (Sigma-Aldrich), itraconazole (Shouguang Pharm, Shandong, China), voriconazole (Shouguang Pharm), posaconazole (Merck, Rahway, NJ, USA), caspofungin (Sigma-Aldrich), and micafungin (Astellas Pharma, Tokyo, Japan) ranged from 0.031 to 16 μg/ml, and the final concentration of terbinafine (Novartis, Basel, Switzerland) ranged from 0.008 to 4 μg/ml. The isolates Candida parapsilosis ATCC 22019, Candida krusei ATCC 6258, Aspergillus flavus ATCC 204304, and Trichophyton mentagrophytes ATCC MYA 4439 were included in each assay run as quality controls.

After 48 h of incubation at 35°C, the MICs were determined visually by comparing the growth in the wells containing the drug to that in the wells containing the drug-free control. Amphotericin B, itraconazole, voriconazole, and posaconazole were found to require the lowest drug concentrations to prevent any discernible growth (100% inhibition), whereas terbinafine required the lowest concentration for ≥80% inhibition. The minimum effective concentration (MEC) was defined as the lowest concentration of drug causing the growth of small, rounded, compact hyphal forms in comparison to the hyphal growth observed in the growth control well for caspofungin and micafungin. The Etest assay was performed at the same time to further confirm the activity of caspofungin. The Etest procedure was performed on RPMI-2G agar plates according to the manufacturer's recommendations (bioMérieux SA, Marcy l'Etoile, France). The results were read and photographed after the plates had been incubated in the dark for 48 h at 35°C.

To determine the species prevalence of Aspergillus section Nigri in China, we used the calmodulin sequences from our isolates and from reference isolates for which sequences are available in public databases to construct a maximum-parsimony tree to identify our isolates. The analysis involved 65 nucleotide sequences that included 22 reference sequences. A total of 530 positions were included in the final data set. Two principal clades were included in the phylogenetic tree: the A. tubingensis clade and the A. niger clade (Fig. 1). The calmodulin gene has the ability to distinguish related reference isolates. In the A. tubingensis clade, the isolate BMU 04778 was close to MUCL 43835, but the two isolates were separated from the rest of the isolates in the A. tubingensis clade. In addition, the isolate Aspergillus piperis CBS 112811 and the isolate Aspergillus neoniger NRRL 62634 were also included in the A. tubingensis clade. This finding prompted us to reidentify BMU 04778 by sequencing the beta-tubulin gene; the isolate was confirmed to be A. tubingensis. In the A. niger clade, Aspergillus lacticoffeatus CBS 101883 was grouped together with A. niger CBS 101700 and A. niger CBS 554.65, as observed in previous studies (4, 10).

FIG 1.

Maximum-parsimony tree based on calmodulin sequences (tree length, 673; consistency index, 0.631579; retention index, 0.880724; and composite index, 0.587586). Bootstrap values of >50% are indicated on the branches.

Thus, 20 of the 43 isolates were identified as A. niger, 23 of the isolates were identified as A. tubingensis, and no other species were found in our collection, highlighting the diversity of black Aspergillus isolates in China. The environmental isolates included 5 A. niger isolates and 11 A. tubingensis isolates, implying that A. tubingensis is more common than A. niger in Chinese environments. The clinical isolates included 15 A. niger isolates and 12 A. tubingensis isolates; both species were cultured from ear and respiratory samples, suggesting that A. niger and A. tubingensis exhibit similar incidence rates among clinical samples. To our knowledge, this study represents the first attempt to correctly identify black Aspergillus isolates from China, and it suggests that both A. niger and A. tubingensis are important black Aspergillus pathogens that cause otomycosis and invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in China.

The geometric mean (GM) MIC/MECs, MIC50/MEC50s (MECs at which 50% of isolates are inhibited), MIC90/MEC90s, and ranges of MIC/MECs for both A. niger and A. tubingensis are presented in Table 1. Both species had low MIC90s for the 7 antifungal drugs. No isolate had an MIC that exceeded the epidemiological cutoff values (ECVs) for azoles (itraconazole, 2 μg/ml; voriconazole, 2 μg/ml; and posaconazole, 0.5 μg/ml) (22). Additionally, 8 isolates, including both species, exhibited paradoxical responses to itraconazole, such that the isolates grew at concentrations of 8 μg/ml and/or 16 μg/ml. Interestingly, 15 and 18 isolates also exhibited this effect in response to caspofungin and micafungin, respectively. The Etest results verified again that caspofungin had good activity against the isolates, but the colony number increased at concentrations ranging from 2 μg/ml to 32 μg/ml.

TABLE 1.

MIC/MECs for black Aspergillus isolates recovered in China

| Druga | MIC/MEC for: |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

A. niger (20)b |

A. tubingensis (23) |

|||||||

| Geometric mean | Range | 50% | 90% | Geometric mean | Range | 50% | 90% | |

| ITR | 0.925 | 0.5–1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| VOR | 0.369 | 0.125–0.5 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.62 | 0.25–2 | 0.5 | 1 |

| POS | 0.175 | 0.125–0.25 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.239 | 0.125–1 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| CAS | 0.108 | 0.031–0.5 | 0.031 | 0.25 | 0.071 | 0.031–0.25 | 0.031 | 0.25 |

| MCFG | 0.042 | 0.031–0.25 | 0.031 | 0.031 | 0.032 | 0.031–0.063 | 0.031 | 0.031 |

| AMB | 0.6 | 0.5–1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.63 | 0.5–1 | 0.5 | 1 |

| TRB | 0.209 | 0.125–0.5 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.402 | 0.25–1 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

ITC, itraconazole; VOR, voriconazole; POS, posaconazole; CAS, caspofungin; MCFG, micafungin; AMB, amphotericin B; TRB, terbinafine.

Numbers in parentheses are numbers of isolates.

The intraspecific and interspecific differences in the antifungal susceptibilities of Aspergillus section Nigri from previous studies were inconsistent (7–13), primarily for the azoles and amphotericin B. Our study also observed the above differences among voriconazole, terbinafine, and amphotericin B, but all the MICs were low for both species. Interestingly, besides itraconazole, the paradoxical effect was observed for the first time in echinocandins on Aspergillus section Nigri.

In conclusion, A. niger and A. tubingensis are the main black Aspergillus species present in clinical and environmental samples in China. Both of these species had low MIC/MECs for common antifungal drugs in vitro, and some of the isolates exhibited a paradoxical effect in response to itraconazole, caspofungin, and micafungin.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The calmodulin sequences determined in this study were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers KM593192 to KM593235, which includes the number KM593222 for the isolate CBS 121.55.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Science and Technology Key Projects on Major Infectious Diseases Such as HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis Prevention and Treatment during the 12th 5-year plan period of the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (grant no. 2013ZX10004612-002).

We declare that we have no relevant conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JCM.03233-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bathoorn E, Escobar Salazar N, Sepehrkhouy S, Meijer M, de Cock H, Haas PJ. 2013. Involvement of the opportunistic pathogen Aspergillus tubingensis in osteomyelitis of the maxillary bone: a case report. BMC Infect Dis 13:59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaya AD, Kiraz N. 2007. In vitro susceptibilities of Aspergillus spp. causing otomycosis to amphotericin B, voriconazole and itraconazole. Mycoses 50:447–450. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2007.01409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walsh TJ, Groll AH. 2001. Overview: non-fumigatus species of Aspergillus: perspectives on emerging pathogens in immunocompromised hosts. Curr Opin Investig Drugs 2:1366–1367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Samson RA, Noonim P, Meijer M, Houbraken J, Frisvad JC, Varga J. 2007. Diagnostic tools to identify black aspergilli. Stud Mycol 59:129–145. doi: 10.3114/sim.2007.59.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abarca ML, Accensi F, Cano J, Cabañes FJ. 2004. Taxonomy and significance of black aspergilli. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 86:33–49. doi: 10.1023/B:ANTO.0000024907.85688.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Varga J, Kocsubé S, Tóth B, Frisvad JC, Perrone G, Susca A, Meijer M, Samson RA. 2007. Aspergillus brasiliensis sp. nov., a biseriate black Aspergillus species with world-wide distribution. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 57:1925–1932. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.65021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hendrickx M, Beguin H, Detandt M. 2012. Genetic re-identification and antifungal susceptibility testing of Aspergillus section Nigri strains of the BCCM/IHEM collection. Mycoses 55:148–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2011.02049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Howard SJ, Harrison E, Bowyer P, Varga J, Denning DW. 2011. Cryptic species and azole resistance in the Aspergillus niger complex. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:4802–4809. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00304-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alcazar-Fuoli L, Mellado E, Alastruey-Izquierdo A, Cuenca-Estrella M, Rodriguez-Tudela JL. 2009. Species identification and antifungal susceptibility patterns of species belonging to Aspergillus section Nigri. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53:4514–4517. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00585-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Szigeti G, Kocsubé S, Dóczi I, Bereczki L, Vágvölgyi C, Varga J. 2012. Molecular identification and antifungal susceptibilities of black Aspergillus isolates from otomycosis cases in Hungary. Mycopathologia 174:143–147. doi: 10.1007/s11046-012-9529-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vermeulen E, Maertens J, Meersseman P, Saegeman V, Dupont L, Lagrou K. 2014. Invasive Aspergillus niger complex infections in a Belgian tertiary care hospital. Clin Microbiol Infect 20:O333–O335. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Szigeti G, Sedaghati E, Mahmoudabadi AZ, Naseri A, Kocsubé S, Vágvölgyi C, Varga J. 2012. Species assignment and antifungal susceptibilities of black aspergilla recovered from otomycosis cases in Iran. Mycoses 55:333–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2011.02103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Balajee SA, Kano R, Baddley JW, Moser SA, Marr KA, Alexander BD, Andes D, Kontoyiannis DP, Perrone G, Peterson S, Brandt ME, Pappas PG, Chiller T. 2009. Molecular identification of Aspergillus species collected for the Transplant-Associated Infection Surveillance Network. J Clin Microbiol 47:3138–3141. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01070-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsiue HC, Wu TH, Chang TC, Hsiue YC, Huang YT, Lee PI, Hsueh PR. 2012. Culture-positive invasive aspergillosis in a medical center in Taiwan, 2000–2009. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 31:1319–1326. doi: 10.1007/s10096-011-1445-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Asano M, Kano R, Makimura K, Hasegawa A, Kamata H. 2011. Molecular typing and in-vitro activity of azoles against clinical isolates of Aspergillus fumigatus and A. niger in Japan. J Infect Chemother 17:483–486. doi: 10.1007/s10156-010-0202-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O'Donnell K, Niremberg H, Aoki T, Cigelnik E. 2000. A multigene phylogeny of the Gibberella fujikuroi species complex: detection of additional phylogenetically distinct species. Mycoscience 41:67–78. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glass NL, Donaldson GC. 1995. Development of primer sets designed for use with the PCR to amplify conserved genes from filamentous ascomycetes. Appl Environ Microbiol 61:1323–1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saitou N, Nei M. 1987. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol 4:406–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Felsenstein J. 1985. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 39:783–791. doi: 10.2307/2408678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kimura M. 1980. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rate of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J Mol Evol 16:111–120. doi: 10.1007/BF01731581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. 2013. MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol 30:2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2008. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of filamentous fungi, 2nd ed. Approved standard CLSI document M38-A2 Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.