Abstract

We report here four cases of continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis-related peritonitis caused by three different species of Gordonia. The portal of entry was likely through Tenckhoff catheters. 16S rRNA and secA1 gene sequencing are so far the most reliable methods for the accurate identification of Gordonia species.

TEXT

Gordonia species are Gram-positive weakly acid-fast coryneform bacteria. Although Gordonia species have been implicated in a variety of infections, only seven cases of continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD)-related peritonitis caused by Gordonia species have been described (1–4). Furthermore, the methods used for identifying these seven Gordonia isolates were not mentioned in five cases (2, 4), and the accuracy of the identifications could not be ascertained. In this article, we described four cases of CAPD-related peritonitis caused by three different species of Gordonia confirmed by 16S rRNA and secA1 gene sequencing.

Clinical specimens were collected and handled according to standard protocols, and the clinical data were collected by analyzing the patients' hospital records. Phenotypic identification was performed using standard conventional biochemical methods and the API Coryne system (bioMérieux, France). All tests were performed in triplicate. The MICs were determined using Etests (bioMérieux), according to the standards of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) (5), with Escherichia coli strain ATCC 25922 and Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain ATCC 27853 as controls; the results were compared with the CLSI MIC interpretive standards for Staphylococcus spp. and Streptococcus pneumoniae (6) for evaluation. Bacterial DNA extraction, PCR amplification, and DNA sequencing of the 16S rRNA and secA1 genes were performed according to our previous publication (7), except for the primer pairs used (G268F/G1096R [8] for the 16S rRNA gene and SecA1-f/SecA1-r [9] for the secA1 gene). Comparative sequence identity analysis and phylogenetic analysis using the maximum likelihood method were performed according to our previous publication (10), except that MEGA 6.06 (11) was used instead. Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) was performed according to our previous publication (12), and the protein profiles obtained were processed and analyzed using MALDI Biotyper 3.1 (Bruker Daltonics, Germany) for the generation of the hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) dendrogram and for identification.

Case 1.

A 65-year-old Chinese man was admitted for cloudy dialysis effluent for 1 day. He had end-stage renal failure (ESRF) of unknown etiology and had been undergoing CAPD for 7 years. He was afebrile but had turbid dialysis effluent. The total leukocyte count of the dialysis fluid was 930/mm3, with neutrophil predominance. A Gram smear of the dialysis effluent after centrifugation revealed numerous leukocytes without any organisms. Empirical intraperitoneal (i.p.) cefazolin and gentamicin therapies were started. As the clinical condition of the patient did not improve, intravenous (i.v.) imipenem-cilastatin and amikacin were commenced and continued for a total of 6 weeks.

Case 2.

A 64-year-old Chinese woman was admitted for abdominal pain and cloudy dialysis effluent for 1 day. She had ESRF due to hypertensive nephropathy and had been undergoing CAPD for 4 years. She was afebrile but had generalized abdominal tenderness and turbid dialysis effluent. The total leukocyte count of the dialysis fluid was >1,000/mm3, with neutrophil predominance. A Gram smear of the dialysis effluent after centrifugation revealed numerous leukocytes and Gram-positive bacilli. Empirical i.p. cefazolin and gentamicin therapies were started. The patient did not respond to i.p. cefazolin and gentamicin, which were stopped after 1 week, and i.v. meropenem and amikacin therapies were commenced. As the response was still unsatisfactory after another 2 weeks, the Tenckhoff catheter was removed, and temporary hemodialysis was commenced. She received three more weeks of i.v. meropenem, followed by 4 weeks of oral levofloxacin.

Case 3.

A 67-year-old Chinese man was admitted for abdominal pain and cloudy dialysis effluent for 1 day. He had ESRF due to diabetic nephropathy and had been undergoing CAPD for 1 year. His Tenckhoff catheter broke 1 week prior to symptom onset. He was afebrile but had generalized abdominal tenderness and turbid dialysis effluent. The total leukocyte count of the dialysis fluid was 1,060/mm3, with neutrophil predominance. A Gram smear of the dialysis effluent after centrifugation revealed numerous leukocytes without any organisms. Empirical i.p. cefazolin and ceftazidime therapies were started. The patient did not respond to i.p. cefazolin and ceftazidime, which were stopped after 1 week, and i.v. imipenem-cilastatin and amikacin therapies were commenced. As the response was still unsatisfactory after another 3 weeks, the Tenckhoff catheter was removed, and temporary hemodialysis was commenced.

Case 4.

A 52-year-old Chinese man was admitted for abdominal pain and cloudy dialysis effluent for 1 day. He had ESRF due to immunoglobulin A nephropathy and had been undergoing CAPD for 1 year. His Tenckhoff catheter broke 2 weeks prior to symptom onset. He was febrile (38.4°C) and had generalized abdominal tenderness and turbid dialysis effluent. The total leukocyte count of the dialysis fluid was 1,030/mm3, with neutrophil predominance. A Gram smear of the dialysis effluent after centrifugation revealed numerous leukocytes without any organisms. Empirical i.p. cefazolin and ceftazidime therapies were started. The patient did not respond to i.p. cefazolin and ceftazidime, which were stopped after 1 week, and the therapy was changed to i.p. vancomycin and amikacin, which were continued for a total of 3 weeks.

The culture of the dialysis effluents of all four patients obtained on admission yielded Gram-positive bacilli (strains PW3022, PW2776, PW3020, and HKU46, respectively). All four isolates grew on horse blood agar as small, light pink, dry, rough, irregular, and nonhemolytic colonies after 5 days of incubation at 37°C in an aerobic environment with 5% CO2. They did not grow under anaerobic conditions. The Gram smears of the colonies showed nonsporulating beaded Gram-positive bacilli, which were acid-fast by modified acid-fast stain. The bacteria were catalase positive but nonmotile. The API Coryne system showed that the four isolates were Rhodococcus species (code: 1110004, 3110004, or 7151104). All four isolates were susceptible to vancomycin, amikacin, imipenem, and ciprofloxacin, with MICs of 0.75 to 1.5 μg/ml, 0.125 to 1 μg/ml, 0.008 to 0.094 μg/ml, and 0.094 to 0.125 μg/ml, respectively.

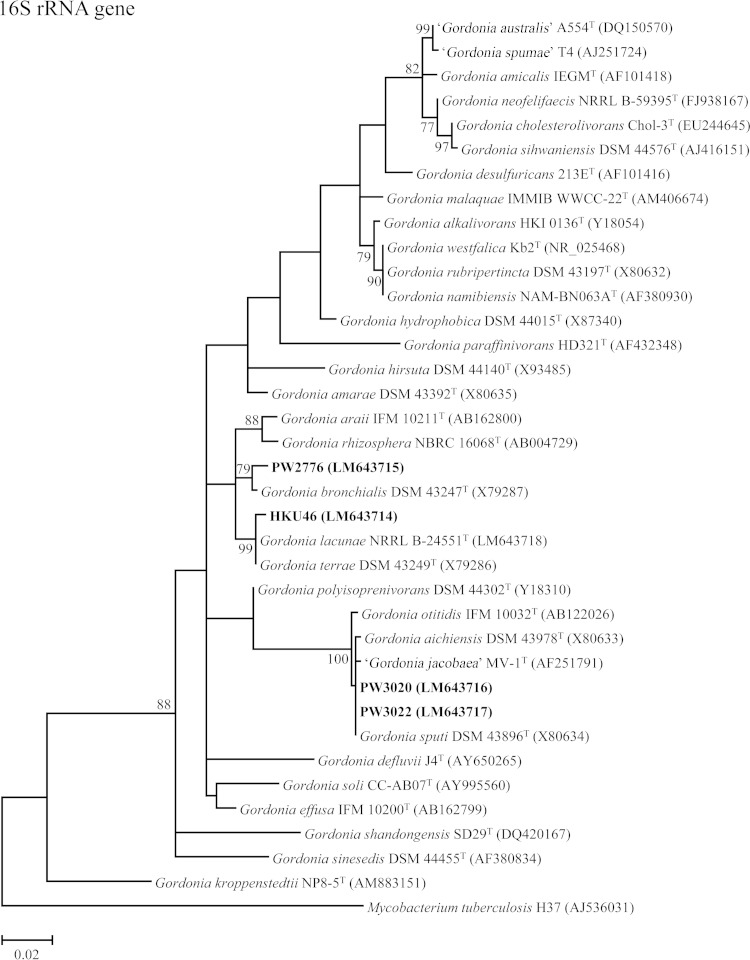

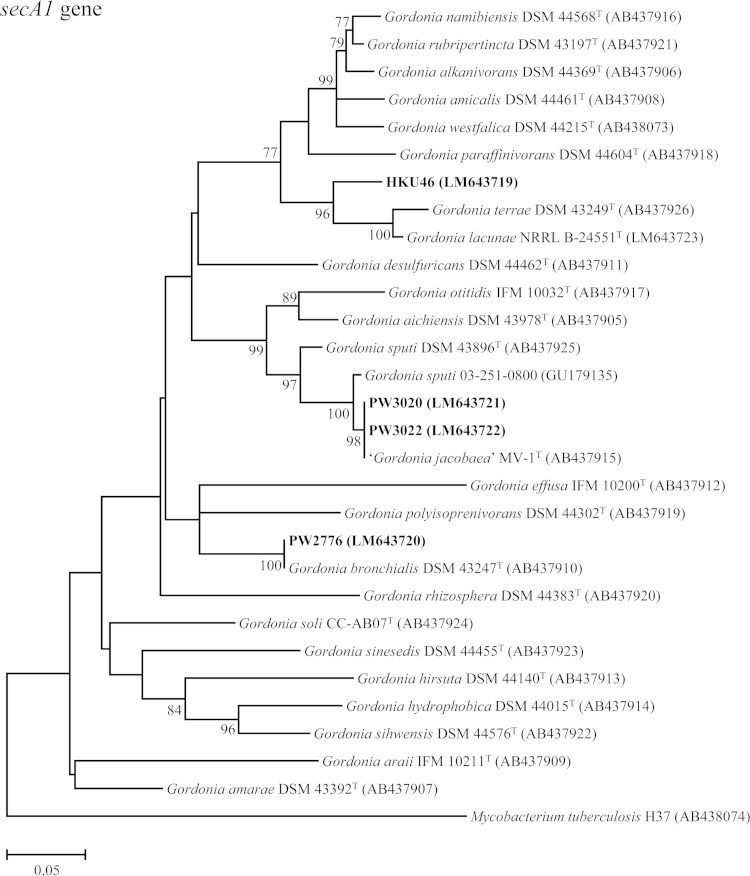

PCR amplification and sequencing of the 16S rRNA and secA1 genes of the four patient isolates and comparative sequence identity analyses showed that strains PW3020 and PW3022 were Gordonia sputi, and strain PW2776 was Gordonia bronchialis (Fig. 1). For strain HKU46, its 16S rRNA gene was found to possess 99.7% sequence identity to that of Gordonia terrae strain DSM 43249T, but its secA1 gene possessed only 94.0% sequence identity to that of Gordonia lacunae strain NRRL B-24551T (Fig. 1), indicating that it was a potentially novel Gordonia species.

FIG 1.

Phylogenetic trees showing the relationship of the four case isolates to Gordonia species. The trees were inferred from partial 16S rRNA and partial secA1 gene sequence data by the maximum likelihood method, with the substitution models T92 (Tamura 3-parameter model) + G (gamma-distributed rate variation) + I (estimated proportion of invariable sites) and GTR (general time-reversible model) + G + I, respectively. Totals of 789 and 469 nucleotide positions of the 16S rRNA and secA1 genes, respectively, were included in the analyses. The scale bars indicate the estimated numbers of substitutions per base. The numbers at the nodes, expressed in percentages, indicate the levels of bootstrap support calculated from 1,000 trees, and bootstrap values of <70 are not shown. All accession numbers (in parentheses) are given as cited in the ENA/GenBank/DDBJ databases, and the names “G. australis,” “G. jacobaea,” and “G. spumae” are not validly published and have no standing in bacterial nomenclature. The case isolates reported in this study are highlighted in bold type.

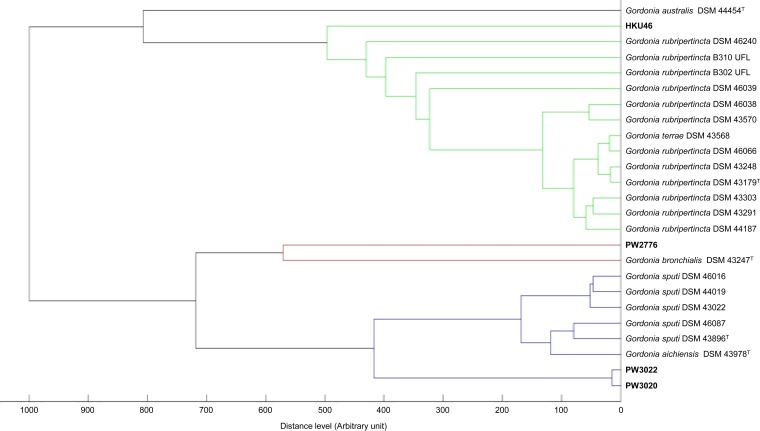

MALDI-TOF MS and HCA showed that PW3020 and PW3022 were clustered with other strains of G. sputi in the database (Fig. 2) and were correctly identified as G. sputi, with top match scores of 2.039 and 2.026, respectively (scores of ≥1.7 and <1.7 to ≥1.5 represent confident identification to the species and genus levels for Gram-positive rods, respectively [13, 14]), whereas PW2776 was clustered with a strain of G. bronchialis in the database (Fig. 2) and was correctly identified as G. bronchialis, with a top match score of 1.743. As for HKU46, MALDI-TOF MS failed to confidently identify this isolate to the species level. However, it was identified as a Gordonia species, with a top match score of 1.550 (as Gordonia rubripertincta), suggesting it did not resemble any known Gordonia species in the database.

FIG 2.

Dendrogram generated from HCA of MALDI-TOF mass spectra of the case isolates and strains of Gordonia species in the Bruker database.

Gordonia species are emerging causes of CAPD-related peritonitis. With the increasing use of 16S rRNA and other housekeeping gene sequencing techniques, bacteria previously not known to be associated with particular clinical syndromes have been reported (15, 16). Since 2012 (i.e., in <3 years), seven cases of CAPD-related peritonitis caused by Gordonia species have been reported (1–4) (Table 1). In the present series, none of the four patients responded to i.p. cefazolin and ceftazidime-gentamicin treatment. When the treatment regimens were switched to i.v. imipenem-cilastatin or meropenem plus amikacin-levofloxacin or i.v./i.p. vancomycin plus amikacin with or without Tenckhoff catheter removal, all four patients responded promptly. This is in line with the treatment response of the seven cases reported in the literature, for which most patients required either i.v. vancomycin or a carbapenem with or without Tenckhoff catheter removal. Notably, CAPD was resumed in seven of the 11 (63.6%) patients afterwards.

TABLE 1.

Summary of reported cases of CAPD peritonitis due to Gordonia speciesa

| Case | Study | Sex/age (yr)b | Underlying condition or riskc | Identity of bacterial isolate | Identification method | Treatmentd | Treatment duration | PD catheter removale | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Imran et al. (1) | F/78 | Gordonia sp. | 16S rRNA gene sequencing | i.v. teicoplanin and i.p. gentamicin | NAf | Yes | NA | |

| 2 | Gardenier et al. (2) | F/50 | Chronic kidney disease due to reflux, breast cancer | Gordonia sp. | Not specified | Amoxicillin-clavulanate | 3 weeks | Yes | Cured and CAPD resumed |

| 3 | Ou et al. (3) | M/69 | ESRD due to diabetic nephropathy | Gordonia sputi | 16S rRNA gene sequencing | 1st and 2nd episodes: i.p. cefazolin plus gentamicin; 3rd episode: i.v. vancomycin plus ceftazidime, and then p.o. ciprofloxacin | 1st and 2nd episodes: 2 weeks; 3rd episode: NA | Yes | Cured, with 2 episodes of recurrence; switched to hemodialysis |

| 4 | Ma et al. (4) | M/45 | ESRD due to immunoglobulin A nephropathy | Gordonia terrae | Not specified | i.p. vancomycin | 3 weeks | No | Cured; cadaveric renal transplant 2 wk after antibiotic was completed |

| 5 | Ma et al. (4) | M/70 | ESRD due to diabetic nephropathy, hypertension, peripheral vascular disease, ischemic heart disease | Gordonia bronchialis | Not specified | i.p. imipenem-cilastatin and amikacin | 2 weeks | No | Cured |

| 6 | Ma et al. (4) | M/61 | Alport syndrome | Gordonia terrae | Not specified | 1st and 2nd episodes: i.p. vancomycin; 3rd episode: i.v. meropenem | 1st and 2nd episodes: 2 weeks; 3rd episode: 2 weeks | Yes | Cured, with 2 episodes of recurrence; CAPD resumed |

| 7 | Ma et al. (4) | M/60 | ESRD of unknown cause | Gordonia terrae | Not specified | i.p. meropenem | NA | Yes | Cured and CAPD resumed |

| 8 | Present case 1 | M/65 | ESRD of unknown cause, hypertension, gout | Gordonia sputi | 16S rRNA and secA1 gene sequencing | i.v. imipenem-cilastatin and amikacin | 6 weeks | No | Cured and CAPD resumed, with no recurrence, succumbed 6 mo later because of Corynebacterium jeikeium and Candida famata CAPD peritonitis |

| 9 | Present case 2 | F/64 | ESRD due to hypertensive nephropathy | Gordonia bronchialis | 16S rRNA and secA1 gene sequencing | i.v. meropenem, and then p.o. levofloxacin | 3 weeks/4 weeks | Yes | Cured and CAPD resumed, with no recurrence |

| 10 | Present case 3 | M/67 | ESRD due to diabetic nephropathy, hypertension, gout, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | Gordonia sputi | 16S rRNA and secA1 gene sequencing | i.v. imipenem-cilastatin and amikacin | 3 weeks | Yes | Cured and CAPD resumed with no recurrence, succumbed 11 mo later because of perforated sigmoid ulcer with secondary peritonitis |

| 11 | Present case 4 | M/52 | ESRD due to immunoglobulin A nephropathy | Potential novel Gordonia sp. | 16S rRNA and secA1 gene sequencing | i.p. vancomycin and amikacin | 3 weeks | No | Cured and CAPD resumed, with no recurrence |

CAPD, continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis.

F, female; M, male.

ESRD, end-stage renal disease.

i.p., intraperitoneal; i.v., intravenous; p.o., oral.

PD, peritoneal dialysis CAPD.

NA, not available.

The portal of entry in these patients with Gordonia CAPD-related peritonitis is likely the Tenckhoff catheter. Pathogens causing CAPD-related peritonitis originate from two major sources, either through the Tenckhoff catheter or by translocating through the intestinal wall. Since Gordonia species are ubiquitous bacteria that have been isolated from environmental samples, such as those from soil and water, it is likely that these bacteria reach the peritoneal cavities of patients undergoing CAPD through their Tenckhoff catheters. In fact, two of the four patients in this study had broken Tenckhoff catheter tips 1 to 2 weeks prior to the development of peritonitis, which likely predisposed those patients to the entry of the Gordonia bacteria into the peritoneal cavities. Notably, Gordonia species have been most commonly reported to be causes of indwelling device-associated infections (17–30), in line with these cases of Gordonia CAPD-related peritonitis.

16S rRNA and secA1 gene sequencing are so far the most reliable ways to accurately identify Gordonia species, which is crucial for understanding the epidemiology, clinical features, treatment, and outcome of infections caused by this group of bacteria. Gordonia are diphtheroids, which are particularly difficult to identify to both the genus and species levels by conventional phenotypic tests. In this study, all four isolates were misidentified as Rhodococcus species by the API Coryne system. 16S rRNA and secA1 gene sequencing accurately identified two isolates as G. sputi and a third one as G. bronchialis. As the secA1 gene of the fourth isolate (HKU46) showed a ≥6% nucleotide difference with the most closely related Gordonia species, G. lacunae and G. terrae, it was likely that it represents a novel Gordonia species, which warranted further characterization. As for MALDI-TOF MS, all three strains of G. sputi and G. bronchialis were confidently identified to the species level, indicating that this technology is potentially also useful for identifying Gordonia species.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The 16S rRNA and secA1 gene sequences have been deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA), European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL), under accession numbers LM643714 to LM643723.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work is partly supported by the Strategic Research Theme Fund, Wong Ching Yee Medical Postgraduate Scholarship, and University Postgraduate Scholarship, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong.

We thank the Agricultural Research Service (ARS) Culture Collection (NRRL) (Department of Agriculture, USA) for providing the reference strain G. lacunae NRRL B-24551T for free.

We declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Imran M, Livesley P, Bell G, Pai P, Neal T, Anijeet H. 2012. Gordona: a rare cause of peritoneal dialysis peritonitis. Perit Dial Int 32:344–346. doi: 10.3747/pdi.2011.00150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gardenier JC, Sawyer RG, Sifri CD, Brayman K, Wispelway B, Bonatti H. 2012. Peritonitis caused by Haemophilus parainfluenzae, Leifsonia aquatica, and Gordonia spp. in a patient undergoing continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 13:409–412. doi: 10.1089/sur.2011.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ou SM, Lee SY, Chen JY, Cheng HW, Wei TH, Yu KW, Lin WM, King KL, Yang WC, Ng YY. 2013. First identification of Gordonia sputi in a continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis patient with peritonitis. Perit Dial Int 33:107–108. doi: 10.3747/pdi.2012.00030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ma TK-W, Chow K-M, Kwan BC-H, Lee K-P, Leung C-B, Li PK-T, Szeto C-C. 2014. Peritoneal-dialysis related peritonitis caused by Gordonia species: report of four cases and literature review. Nephrology 19:379–383. doi: 10.1111/nep.12233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). 2012. Performance standards for antimicrobial disk susceptibility tests; approved standard, 11th ed. CLSI document M02-A11. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). 2013. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; twenty-third informational supplement. CLSI document M100-S23. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Woo PCY, Fung AMY, Lau SKP, Wong SSY, Yuen K-Y. 2001. Group G beta-hemolytic streptococcal bacteremia characterized by 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequencing. J Clin Microbiol 39:3147–3155. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.9.3147-3155.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shen FT, Young CC. 2005. Rapid detection and identification of the metabolically diverse genus Gordonia by 16S rRNA-gene-targeted genus-specific primers. FEMS Microbiol Lett 250:221–227. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2005.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kang Y, Takeda K, Yazawa K, Mikami Y. 2009. Phylogenetic studies of Gordonia species based on gyrB and secA1 gene analyses. Mycopathologia 167:95–105. doi: 10.1007/s11046-008-9151-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woo PCY, Wu AKL, Tsang C-C, Leung K-W, Ngan AHY, Curreem SOT, Lam K-W, Chen JHK, Chan JFW, Lau SKP. 2014. Streptobacillus hongkongensis sp. nov., isolated from patients with quinsy and septic arthritis, and emended descriptions of the genus Streptobacillus and Streptobacillus moniliformis. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 64:3034–3039. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.061242-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. 2013. MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol 30:2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lau SKP, Tang BSF, Teng JLL, Chan T-M, Curreem SOT, Fan RYY, Ng RHY, Chan JFW, Yuen K-Y, Woo PCY. 2014. Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionisation time-of-flight mass spectrometry for identification of clinically significant bacteria that are difficult to identify in clinical laboratories. J Clin Pathol 67:361–366. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2013-201818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alatoom AA, Cazanave CJ, Cunningham SA, Ihde SM, Patel R. 2012. Identification of non-diphtheriae Corynebacterium by use of matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry. J Clin Microbiol 50:160–163. doi: 10.1128/JCM.05889-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barberis C, Almuzara M, Join-Lambert O, Ramírez MS, Famiglietti A, Vay C. 2014. Comparison of the Bruker MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry system and conventional phenotypic methods for identification of Gram-positive rods. PLoS One 9:e106303. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woo PCY, Fong AHC, Ngan AHY, Tam DMW, Teng JLL, Lau SKP, Yuen K-Y. 2009. First report of Tsukamurella keratitis: association between T. tyrosinosolvens and T. pulmonis and ophthalmologic infections. J Clin Microbiol 47:1953–1956. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00424-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Woo PCY, Teng JLL, Lam KKM, Tse CWS, Leung KW, Leung AWS, Lau SKP, Yuen KY. 2010. First report of Gordonibacter pamelaeae bacteremia. J Clin Microbiol 48:319–322. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01459-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buchman AL, McNeil MM, Brown JM, Lasker BA, Amentn ME. 1992. Central venous catheter sepsis caused by unusual Gordona (Rhodococcus) species: identification with a digoxigenin-labeled rDNA probe. Clin Infect Dis 15:694–697. doi: 10.1093/clind/15.4.694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lesens O, Hansmann Y, Riegel P, Heller R, Benaissa-Djellouli M, Martinot M, Petit H, Christmann D. 2000. Bacteremia and endocarditis caused by a Gordonia species in a patient with a central venous catheter. Emerg Infect Dis 6:382–385. doi: 10.3201/eid0604.000410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pham AS, Dé I, Rolston KV, Tarrand JJ, Han XY. 2003. Catheter-related bacteremia caused by the nocardioform actinomycete Gordonia terrae. Clin Infect Dis 36:524–527. doi: 10.1086/367543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kempf VAJ, Schmalzing M, Yassin AF, Schaal KP, Baumeister D, Arenskötter M, Steinbüchel A, Autenrieth IB. 2004. Gordonia polyisoprenivorans septicemia in a bone marrow transplant patient. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 23:226–228. doi: 10.1007/s10096-003-1087-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blaschke AJ, Bender J, Byington CL, Korgenski K, Daly J, Petti CA, Pavia AT, Ampofo K. 2007. Gordonia species: emerging pathogens in pediatric patients that are identified by 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequencing. Clin Infect Dis 45:483–486. doi: 10.1086/520018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grisold AJ, Roll P, Hoenigl M, Feierl G, Vicenzi-Moser R, Marth E. 2007. Isolation of Gordonia terrae from a patient with catheter-related bacteraemia. J Med Microbiol 56:1687–1688. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.47388-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brust JCM, Whittier S, Scully BE, McGregor CC, Yin MT. 2009. Five cases of bacteraemia due to Gordonia species. J Med Microbiol 58:1376–1378. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.010272-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jannat-Khah DP, Halsey ES, Lasker BA, Steigerwalt AG, Hinrikson HP, Brown JM. 2009. Gordonia araii infection associated with an orthopedic device and review of the literature on medical device-associated Gordonia infections. J Clin Microbiol 47:499–502. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01504-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Renvoise A, Harle JR, Raoult D, Roux V. 2009. Gordonia sputi bacteremia. Emerg Infect Dis 15:1535–1537. doi: 10.3201/eid1509.080903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gupta M, Prasad D, Khara HS, Alcid D. 2010. A rubber-degrading organism growing from a human body. Int J Infect Dis 14:e75–e76. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lai CC, Wang CY, Liu CY, Tan CK, Lin SH, Liao CH, Chou CH, Huang YT, Lin HI, Hsueh PR. 2010. Infections caused by Gordonia species at a medical centre in Taiwan, 1997 to 2008. Clin Microbiol Infect 16:1448–1453. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kofteridis DP, Valachis A, Scoulica E, Christidou A, Maraki S, Samonis G. 2012. Hickman catheter-related bacteremia caused by Gordonia sputi in a patient with breast cancer. J Infect Dev Ctries 6:188–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moser BD, Pellegrini GJ, Lasker BA, Brown JM. 2012. Pattern of antimicrobial susceptibility obtained from blood isolates of a rare but emerging human pathogen, Gordonia polyisoprenivorans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:4991–4993. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01251-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramanan P, Deziel PJ, Wengenack NL. 2013. Gordonia bacteremia. J Clin Microbiol 51:3443–3447. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01449-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]