Abstract

Advanced glottic cancer (T3,N+ & T4) is usually treated in the majority of centres by total laryngectomy. Carcinoma of the larynx is one of the very few subsets of all cancers which have shown a decrease in the 5 year survival rate and this phenomenon has been attributed to a Pharyngo-cutaneous fistula is the most common complication after total laryngectomy. Comparative study between double layered repair of pharyngeal mucosa against routine single layered repair in cases of “total laryngectomy with partial pharyngectomy”. All patients with the principal procedure of “total laryngectomy with partial pharyngectomy” in department of otorhinolaryngology and head-neck surgery, Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose Medical College, Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh, India were included in this study. Out of the 20 patients who had undergone total laryngectomy irrespective of the type of mucosal repair, 5 (25 %) patients developed pharyngocutaneous fistula. Out of the 8 patients, with double layered mucosa repair, 1 (12.5 %) patient developed pharyngocutaneous fistula. Out of the 12 patients, with single layered mucosa repair, 4 (33 %) patients developed pharyngocutaneous fistula. Double layered repair of pharyngeal mucosa is associated with a lower incidence of pharyngocutaneous fistula formation and no increased incidence of dysphagia after complete radiotherapy as compared to single layered repair.

Keywords: Pharyngo-cutaneous fistula, Laryngeal neoplasms, Total laryngectomy, Postoperative complications

Introduction

Historically, the first total laryngectomy was performed by Dr. Billroth in 1873 in a patient suffering from carcinoma of the larynx. In this instance, the post-operative phase was complicated by the development of a pharyngo-cutaneous fistula which eventually closed and allowed the patient to return to an oral diet. However, he developed a recurrence of his disease and later succumbed from it. For more than a century thereafter, total laryngectomy became a common and curative treatment employed for advanced laryngeal carcinoma with the expectation that individuals would retain normal deglutition function and regain a functional means of speaking. Since that time, many variations of the technique have been developed, and most of the emphasis has been on preventing complications and improving means of communication.

Pharyngo-cutaneous fistula is still the most common post-operative complication developing in patients undergoing total laryngectomy with partial pharyngectomy, irrespective of the indications of the procedure.

This study aims to compare different types of mucosal repairs with

Pharyngo-cutaneous fistula formation and

Post-treatment dysphagia as outcome.

Aims and Objectives

Comparative study between double layered repair of pharyngeal mucosa against routine single layered repair in cases of “total laryngectomy with partial pharyngectomy” in respect to formation of fistula.

To compare incidence of dysphagia after completion of radiotherapy regimes in the above mentioned groups.

Subjects and Methods

All patients with the principal procedure of “total laryngectomy with partial pharyngectomy” for histopathologically proven cases of carcinoma larynx and pyriform fossa in the department of otorhinolaryngology and head-neck surgery, Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose Medical College, Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh, India were included.

Regardless of the indications of the procedure or the stage of the disease in which the patient presented, the patients were categorized into two cohorts

Those in which mucosa was repaired in single layer as done routinely.

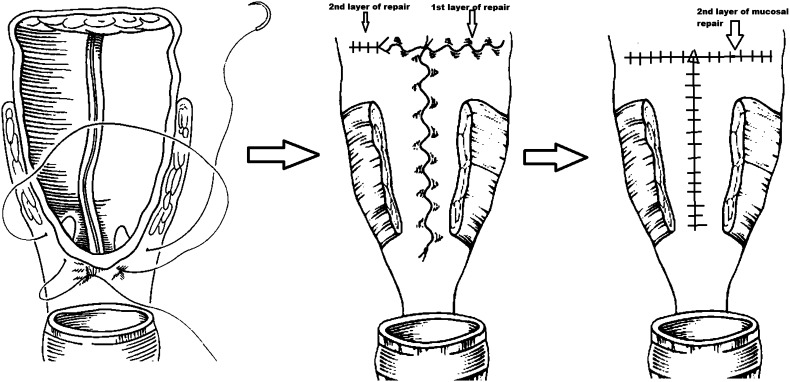

Those in which mucosa was repaired in two layers i.e. 1st layer of Connell’s sutures and 2nd layer of simple or continuous sutures covering 1st layer completely (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Diagrammatic representation of mucosal repair

Repair of overlying muscles, fascia and skin was done in a similar way in all the study subjects and if significant difference was noted, for e.g. torn or deficient fascia or muscles, the subject was excluded from the study.

The patient’s post surgical wound in all cases was cleaned and dressed daily and patient was observed for presence of any fistulous discharge (i.e. associated with deglutition). The cases which presented with purulent discharge but were not associated with deglutition or those which responded to antibiotics were not categorized as fistula formation.

Observations and Results

All the patients included in the study were males (20 i.e. 100 %).

Most of the patients 10 (50 %) belonged to the age group of 51–65 with distribution as: (Table. 1)

Out of the 20 patients who had undergone total laryngectomy irrespective of type of mucosal repair, 5 (25 %) patients developed pharyngo-cutaneous fistula. (Table. 2)

Out of the 12 patients, with single layered mucosa repair, 4 (33 %) patients developed pharyngo-cutaneous fistula. (Table. 3)

Out of the 8 patients, with double layered mucosa repair, only 1 (12.5 %) patient developed pharyngo-cutaneous fistula. (Table. 4)

Table 1.

Age distribution of the patients

| S.no. | Age group(In Years) | No. of patients | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0–20 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 21–35 | 1 | 5 |

| 3 | 36–50 | 7 | 35 |

| 4 | 51–65 | 10 | 50 |

| 5 | 66–80 | 2 | 10 |

| Total | 20 |

Table 2.

Overall fistula formation irrespective of the type of repair

| S.no. | Patient undergone total laryngectomy | No. of patients | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fistula formation | 5 | 25 |

| 2 | No fistula formation | 15 | 75 |

| Total | 20 |

Table 3.

Incidence of fistula formation in single layered repair

| S.no. | Patient with single layered repair | No. of patients | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fistula formation | 4 | 33.33 |

| 2 | No fistula formation | 8 | 66.6 |

| Total | 12 |

Table 4.

Incidence of fistula formation in double layered repair

| S.no. | Patient with double layered repair | No. of patients | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fistula formation | 1 | 12.5 |

| 2 | No fistula formation | 7 | 87.5 |

| Total | 8 |

Discussion

Patients with poor pre-operative nutritional status and positive surgical margins and those with diabetes are at high risk for fistula development [12]. Early studies [11, 13] did not show a significantly increased fistula rate in patients who have had preoperative radiotherapy, but subsequent studies seem to refute this [10, 12, 14–16]. A fistula begins as a major accumulating salivary leak from the pharyngeal closure into the subcutaneous space beneath the skin flaps and may be encouraged by a tight distal hypopharyngeal closure.

Fistulae may develop at any point after surgical excision, but most frequently occur in the first few weeks. Depending on the location, pharyngo-cutaneous, oro-cutaneous fistulae are more common in patients requiring more extensive resections, especially including pharyngectomy or when surgery is performed as a salvage procedure after failed chemoradiation (Starmer et al. 2008). Post-operative infections also increase the likelihood of developing fistulae [17].

The factors known to be associated with increased incidence are inadequate surgery, and hematoma of the surgical wound. In cases of late fistulization, second primary tumor of the pyriform sinus must be considered [2–6]. Though there are many other factors that may also be related to the incidence of PCF such as age, sex, smoking and alcohol consumption during the disease, liver function, hemoglobin status, previous radiotherapy, previous tracheostomy, neck dissection, comorbidities (diabetes, decompensated congestive heart failure, malnutrition, and chronic bronchitis) and postoperative vomiting.

PCF leads to significantly increased morbidity, duration of hospitalization, and financial burden, in addition to delaying the start of indicated adjuvant therapy [1] like radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Salivary fistulae also cause considerable discomfort as patients have to be fed through nasogastric tubes [2]. The literature reports PCF incidence rates ranging from 3 % to 65 % [7–9].

In our study, overall incidence of PCF was 25 %. Incidence with single layered mucosal repair was about 33.3 % and the incidence with double layered repair was 12.5 %.

Conclusion

The authors conclude that double layered repair of pharyngeal mucosa is associated with low incidence of pharyngo-cutaneous fistula formation. Thus increased efforts and time taken during surgery is justified as it results in significantly reduction in morbidity.

Also that such a modification does not increase the incidence of dysphagia (e.g. by compromising mucosal lumen) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Comparison of patients having dysphagia after completion of radiotherapy

| S.no. | Patient c/o dysphagia | No. of patients | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Single layered repair | 1/12 | 8.3 |

| 2 | Double layered repair | 1/8 | 12.5 |

| Total | 2 |

References

- 1.Cavalot AL, Gervasio CF, Nazionale G, Albera R, Bussi M, Staffieri A, et al. Pharyngocutaneous fistula as a complication of total laryngectomy: review of the literature and analysis of case records. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;123(5):587–592. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2000.110617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galli J, De Corso E, Volante M, Almadori G, Paludetti G. Postlaryngectomy pharyngocutaneous fistula: incidence, predisposing factors, and therapy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;133(5):689–694. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parikh SR, Irish JC, Curran AJ, Gullane PJ, Brown DH, Rotstein LE. Pharyngocutaneous fistulae in laryngectomy patients: the Toronto Hospital experience. J Otolaryngol. 1998;27(3):136–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tomkinson A, Shone GR, Dingle A, Roblin DG, Quine S. Pharyngocutaneous fistula following total laryngectomy and post-operative vomiting. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1996;21(4):369–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.1996.tb01090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Venegas MP, León X, Quer M, Matiño E, Montoro V, Burgués J. Complications of total laryngectomy in relation to the previous radiotherapy. Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp. 1997;48(8):639–646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Markou KD, Vlachtsis KC, Nikolaou AC, Petridis DG, Kouloulas AI, Daniilidis IC. Incidence and predisposing factors of pharyngocutaneous fistula formation after total laryngectomy. Is there a relationship with tumor recurrence? Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2004;261(2):61–67. doi: 10.1007/s00405-003-0643-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bresson K, Rasmussen H, Rasmussen PA. Pharyngo-cutaneous fistulae in totally laryngectomized patients. J Laryngol Otol. 1974;88(9):835–842. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100079433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thawley SE. Complications of combined radiation therapy and surgery for carcinoma of the larynx and inferior hypopharynx. Laryngoscope. 1981;91(5):677–700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Virtaniemi JA, Kumpulainen EJ, Hirvikoski PP, Johansson RT, Kosma VM. The incidence and etiology of postlaryngectomy pharyngocutaneous fistulae. Head Neck. 2001;23(1):29–33. doi: 10.1002/1097-0347(200101)23:1<29::AID-HED5>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weber RS, Berkey BA, Forastiere A, et al. Outcome of salvage total laryngectomy following organ preservation therapy: the radiation therapy oncology group trial 91–11. J Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129:44. doi: 10.1001/archotol.129.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sessions DG, Ogura JH, Fried MP. Carcinoma of the subglottic area. Laryngoscope. 1975;85:1417. doi: 10.1288/00005537-197509000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thawley SE. Complications of combined radiation therapy and surgery for carcinoma of the larynx and inferior hypopharynx. Laryngoscope. 1981;41:677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grau C, Johansen LV, Hansen HS. Salvage laryngectomy and pharyngocutaneous fistulae after primary radiotherapy for head and neck cancer: a national survey from DAHANCA. Head Neck. 2003;25:711. doi: 10.1002/hed.10237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Virtaniemi JA, et al. The incidence and etiology of postlaryngectomy pharyngocutaneous fistulae. Head Neck. 2001;23:29. doi: 10.1002/1097-0347(200101)23:1<29::AID-HED5>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ganly I, Patel S, Matsuo J, et al. Postoperative complications of salvage total laryngectomy. Cancer. 2005;15:2073–2078. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwarts SR, Yueh B, Maynard C, et al. Predictors of wound complications after laryngectomy: a study of over 2000 patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;131:61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2003.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mario A. Landera, Donna S. Lundy, Paula A. Sullivan: Dysphagia After Total Laryngectomy. Journals.asha 2010; 40–44