Abstract

Hematogenous metastasis is the most common form of metastasis in head and neck cancer, and reports have described successful resection of pulmonary metastases of such cancers. We report treatment outcomes after surgical resection of pulmonary metastases of head and neck cancer and identify prognostic factors. This clinicopathologic study investigated the clinical records of 16 patients with pulmonary metastases of head and neck cancer (excepting cases of thyroid cancer) who had undergone metastasectomy at our center during the period 2001–2012. The mean age of the 16 patients (11 men and 5 women) was 62.1 years. The mean interval between completion of successful treatment of the primary tumor and detection of pulmonary metastasis was 21 months (range, 6–56 months). All patients underwent pulmonary resection. The overall 1-year survival rate was 79.4 %, and the 2- to 5-year survival rate was 63.2 %. These rates compare favorably to those in previous reports on resection of pulmonary metastases. When prognostic factors for survival rates were compared, the factors associated with a negative prognosis were a disease-free interval of <12 months and partial resection of pulmonary metastases. Multivariate analysis did not reveal any prognostic factors associated with negative outcomes. Surgical resection of pulmonary metastases of head and neck cancer might improve outcomes.

Keywords: Head and neck carcinoma, Pulmonary metastasis, Surgical resection, Prognostic factor

Introduction

Recent studies of head and neck cancer indicate that multimodal therapy, including chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and surgery, is more effective in treating localized tumors. Nevertheless, despite adequate local control, distant metastases frequently develop and are associated with unfavorable outcomes [1, 2]. The most common metastasis of head and neck carcinoma is hematogenous metastasis to the lungs; however, there are few data on survival rates after metastasectomy, and treatment in most reported cases did not include surgical resection of distant metastases. We describe treatment outcomes after resection of pulmonary metastases of head and neck cancer and attempt to identify factors associated with prognosis.

Subjects and Methods

The subjects of the present study were 16 patients with head and neck carcinoma who presented for treatment at the Otorhinolaryngology Department of Niigata University Medical and Dental General Hospital during 2001–2012 and underwent surgical resection of subsequent pulmonary metastases of these primary tumors. The four criteria used to determine suitability for surgical resection of pulmonary metastases were [1] presence of metastasis from a malignant tumor in the head or neck (excepting the thyroid), [2] complete response to radical therapy for the primary lesion and sustained complete remission of cancer thereafter, [3] no other distant metastases, and [4] complete pulmonary resection not contraindicated. We retrospectively reviewed treatment outcomes for these 16 cases of resected pulmonary metastases and attempted to identify clinicopathologic factors associated with prognosis.

At our hospital, after a complete response following radical therapy for head and neck cancer, the patient is carefully monitored during regular visits, at which time CT scans are obtained every 3 months. The time at which a pulmonary metastasis was suspected was defined as the time of onset of the metastatic lesion by Radiologists. The pulmonary lesions were considered metastatic, if they showed new, rounded pulmonary lesions without carcifications in patients previously known to have head and neck carcinoma. All patients underwent resection of their pulmonary metastases in Thoracic Surgery Department of Niigata University Medical and Dental General Hospital. They were resected partially with smallest safety margin and performed all pulmonary metastases excision at the same time. No serious postoperative complications were observed, and there were no operative or perioperative deaths.

All specimens obtained from metastasectomies were reviewed by several pathologists. The pulmonary lesions were considered metastatic only if pathologists could exclude the possibility of a primary lung malignancy and define the tumor as metastatic based upon histologic similarity to primary tumor, especially for squamous cell carcinoma.

The stage of the primary lesion was determined according to the International Union Against Cancer (UICC) and Pittsburgh staging systems [3], and survival rates after pulmonary resection were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method. The log-rank test was used to evaluate differences between survival rates, and Cox proportional hazards models were used in all multivariate analysis. Differences were considered to be statistically significant when p was <0.05.

Results

Table 1 shows the background characteristics of the 16 patients. There were 11 men and 5 women; mean age was 62.1 years (range, 44–78 years). The site of the primary tumor was the larynx in six cases, the hypopharynx in four cases, the major salivary glands in three cases, and the oral cavity, oropharynx, and external auditory canal in one case each. Tumor stage was T2 in five cases, T3 in six cases, and T4 in five cases. Nodal status was N0 in six cases, N1 in two cases, and N2 in eight cases. No T1 or N3 cases were seen. Two patients had stage II, four had stage III, and ten had stage IV cancer.

Table 1.

Clinical features of primary cancer

| Variable | |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 11 |

| Female | 5 |

| Age | |

| Median (range) | 62.1 (44–78) |

| Primary site | |

| Larynx | 6 |

| Hypopharynx | 4 |

| Salivary gland | 3 |

| Oral cavity | 1 |

| Mesopharynx | 1 |

| External auditory canal | 1 |

| Tumor stage | |

| 1 | 0 |

| 2/3/4 | 5/6/5 |

| Node status | |

| 0 | 6 |

| 1/2/3 | 2/8/0 |

| Disease stage | |

| 1 | 0 |

| II | 2 |

| III | 4 |

| IV | 10 |

Table 2 shows the initial treatments for the primary cancers: 11 patients underwent surgery (three of whom received postoperative radiotherapy), and five received chemoradiotherapy. Eleven patients had squamous cell carcinoma and five did not (i.e., two cases of adenoid cystic carcinoma and one each of adenocarcinoma not otherwise specified, myoepithelial carcinoma, and salivary duct carcinoma).

Table 2.

Initial treatment and histology of primary cancer

| Variable | |

|---|---|

| Initial treatment | |

| Surgery | 11 |

| Chemoradiotherapy | 5 |

| Histologic type | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 11 |

| Adenoid cystic carcinoma | 2 |

| Adenocarcinoma, NOS | 1 |

| Myoepithelial carcinoma | 1 |

| Salivary duct carcinoma | 1 |

Table 3 shows the clinical characteristics of pulmonary metastases. The median disease-free interval (DFI) was 21 months (range, 6–56 months). Eight patients had a single metastasis and eight had multiple metastases (range, 2–11 lesions). All patients underwent pulmonary resection—complete resection in 13 cases and partial resection in three cases. No patient died during or immediately after surgery, and there were no cases of postoperative complications. The mean duration of postoperative observation is 26 months (range, 2–96 months) at this writing. There has been no recurrence in ten cases, one case of recurrence in a surviving patient, and five deaths due to the primary cancer (Hypopharynx:3, Oral cavity:1, Salivary gland:1).

Table 3.

Clinical characteristics of pulmonary metastases

| Variable | |

|---|---|

| Median disease-free interval, months (range) | 21 (6–56) |

| Number of metastases | |

| Single | 8 |

| Multiple (range: 2–11) | 8 |

| Largest size of metastases, mm; mean (range) | 8.4 (3–15) |

| Laterality of metastases | |

| Unilateral | 12 |

| Bilateral | 4 |

| Completeness of resection | |

| Complete | 13 |

| Partial | 3 |

| Follow-up period, months; median (range) | 26 (2–96) |

| Outcome | |

| Alive, no recurrence | 10 |

| Alive, recurrence | 1 |

| Death with head and neck carcinoma | 5 |

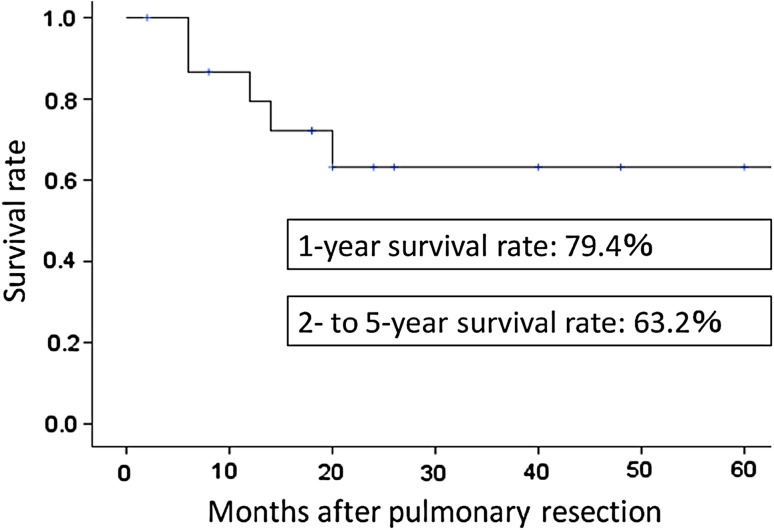

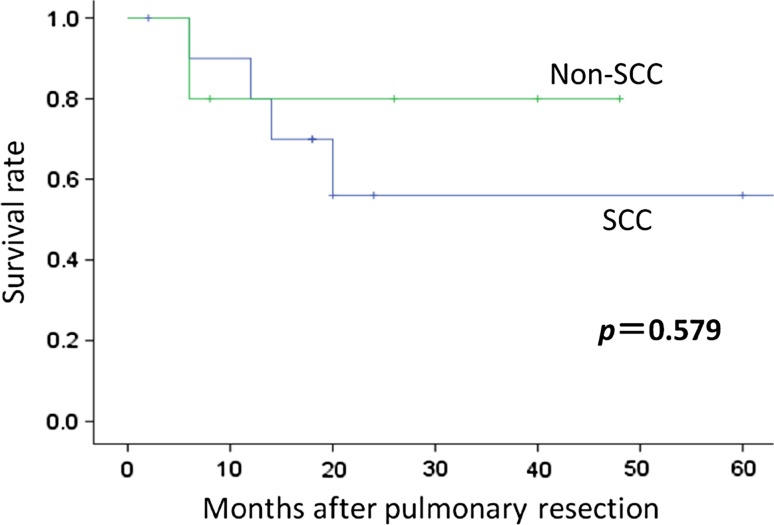

The postoperative survival rates for the 16 patients were 79.4 % at 1 year and 63.2 % at 2–5 years (Fig. 1). Histologic analysis showed that patients with squamous cell carcinomas had a 1-year survival rate of 80.0 %, but this markedly decreased to 56.0 % at 2 years. In contrast, patients who did not have squamous cell carcinoma had a similar 1-year survival rate (80.0 %) but better long-term survival (80.0 % at 2 years). However, the difference between these groups was not significant (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Kaplan–Meier survival curve for 16 patients undergoing pulmonary resection

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves for overall survival among patients with and without squamous cell carcinoma

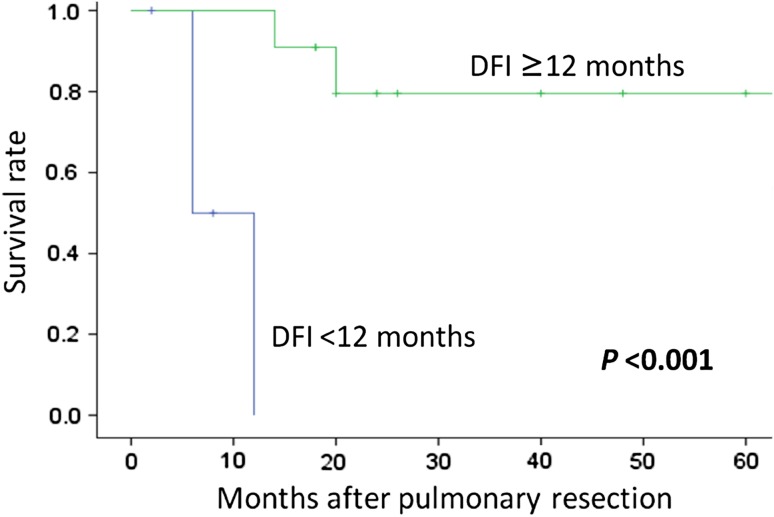

Patients with a DFI ≥ 12 months had a 1-year survival rate of 90.9 % and a 2-year survival rate of 79.5 %. In contrast, those with a DFI < 12 months all died within 1 year postoperatively. DFI was significantly associated with survival rate (Fig. 3). Table 4 shows the results of univariate analysis comparing patient age; stage classification, treatment, and histologic characteristics of primary tumors; DFI; number and location of pulmonary metastases; and extent of resection. Only DFI (p < 0.001) and extent of resection (complete vs. partial; p = 0.002) were significantly associated with survival time. Table 5 shows the results of multivariate analysis using Cox proportional hazards models. No factor was significantly independently associated with overall survival.

Fig. 3.

Kaplan–Meier curves for overall survival among patients with a DFI ≥ 12 or <12 months

Table 4.

Results of univariate analysis (Log-rank test)

| Factor | Subgroup | 1-year survival (%) | 2-year survival (%) | Log-rank test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | <63 (10) | 68.6 | 57.1 | p = 0.392 |

| ≥63 (6) | 66.7 | 66.7 | ||

| Stage | II + III (6) | 100 | 80.0 | p = 0.334 |

| IV (10) | 66.7 | 53.3 | ||

| Treatment | Surgery (11) | 90.0 | 63.0 | p = 0.733 |

| CCRT (5) | 60.0 | 60.0 | ||

| Histology | SCC (11) | 80.0 | 56.0 | p = 0.579 |

| non-SCC (5) | 80.0 | 80.0 | ||

| DFI (months) | <12 (5) | 0.0 | 0.0 | p < 0.001 |

| >12 (11) | 90.9 | 79.5 | ||

| Number of metastases | Solitary (8) | 85.7 | 51.4 | p = 0.526 |

| Multiple (8) | 87.5 | 75.0 | ||

| Laterality of metastases | Unilateral (12) | 80.8 | 58.9 | p = 0.752 |

| Bilateral (4) | 75.0 | 75.0 | ||

| Outcome of metastasectomy | Complete resection (13) | 90.9 | 81.8 | p = 0.002 |

| Partial resection (3) | 33.3 | 0.0 |

Table 5.

Factors associated with overall survival in multivariate analysis

| Factor | Subgroup | Hazard ratio | 95 % Confidence interval | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DFI | ≧12 | 0.01 | 0.0–29,641.96 | 0.421 |

Discussion

Previous reports have revealed favorable outcomes after surgical resection of metastatic pulmonary lesions. Many studies have noted significantly longer survival after such procedures, especially when the primary tumor was located in hard or soft tissue, or in the large intestine [4, 5]. Pulmonary metastases of head and neck cancer have been reported in 1.6–23 % of cases [6]; however, few reports have examined the effectiveness of surgical resection of pulmonary metastases of head and neck cancer.

The prognosis of patients with metastatic head and neck cancer is generally poor, and most such patients are treated with methods other than surgical resection. Lefor et al. reported that median survival time (MST) when lung metastases of head and neck cancer were left untreated was only 3 months, and that the 1-year survival rate was a disappointing 7 % [7]. Another recent study that used molecular-targeted drugs to treat recurrent and metastatic head and neck cancer reported an MST of 5.2–8.1 months, and a 1-year survival rate of 20–30 % [8].

In contrast, pulmonary metastasectomy resulted in an overall 1-year survival rate of 79.4 % and a 2- to 5-year survival rate of 63.2 % in the present study. These rates are much more encouraging than those reported in earlier studies. Nibu et al. reported a 5-year survival rate of 32 % among 32 patients with surgically resected pulmonary metastases of head and neck cancer [9]. A study by Wedman et al. compared 18 patients with pulmonary metastases of head and neck cancer. Overall 5-year survival was 4 % among those had not undergone resection and 59 % among those who had undergone resection [6]. A recent study by Daiko et al. reported a 1-year survival rate of 76 % for 33 patients who had undergone pulmonary metastasectomy (3-year survival rate, 43 %, MST, 21 months) [10]. In addition, a study of 114 patients who had undergone pulmonary metastasectomy reported a 5-year survival rate of 26.5 % and an MST of 26 months [11]. Similar to patients with primary cancer of the large intestine or hard and soft tissues, past and present results indicate that resection is indicated for pulmonary metastases of head and neck cancer, as it is associated with better outcomes.

In our department, only patients for whom lung resection alone is sufficient are considered for pulmonary metastasectomy. Patients who require resection of surrounding tissue or the pulmonary lobes are not considered suitable for this procedure. These selection criteria may partly explain our relatively high survival rates.

In an analysis of factors affecting postoperative survival, patients with a DFI of <12 months and those who had undergone partial resection had significantly worse outcomes. However, multivariate analysis showed no significant effect on prognosis for any factor. Nevertheless, Wedman et al. [6] and Nibu et al. [9] found that a DFI of <12 months was associated with poor prognosis. This finding suggests that a DFI of ≥12 months is an important factor when determining the suitability of a patient for pulmonary metastasectomy.

Wedman et al. [6] and Shiono et al. [11] found that partial resection was associated with poor prognosis, which was confirmed in the present study. In our department, metastasectomy is typically considered only for patients who are candidates for complete resection, and the question remains as to why three of the present 16 patients underwent partial resection. Tumor stage, tumor histology, and number of metastases were not associated with an unfavorable prognosis. Thus, present and past findings provide empirical support for metastasectomy (including complete resection)—and our basic approach toward metastatic lesions (surgical resection, if possible)—for patients with a DFI of ≥12 months.

It is unclear whether the present cases of lung squamous cell carcinoma were actually metastases of head and neck carcinoma or de novo squamous cell carcinoma, i.e., new primary lesions in the lung. It may be impossible to answer this question with certainty [12]. When the primary lesion occurs in the lung, the standard surgical procedure is lobectomy, but in cases of metastasis, the smallest possible area should be excised, while maintaining adequate margins. Future studies should attempt to identify biomarkers that indicate the location of primary lesions in squamous cell carcinoma. However, at present, it seems prudent to consider the time required for pulmonary lesions (or metastases) to develop and to carefully examine CT results to determine the size of the area to be resected for safety.

Conclusion

We retrospectively analyzed data from 16 patients who underwent resection of pulmonary metastases of head and neck cancer at our hospital. The post-metastasectomy 5-year survival rate was 63.2 %, which suggests that, at present, metastasectomy results in the best outcomes for such patients. Patients with a DFI of ≥12 months, irrespective of tumor stage, tumor histology, or number of metastatic lesions, are particularly suitable for metastasectomy. However, further studies, with greater numbers of cases, are necessary to confirm our findings.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- 1.Vikram B. Changing patterns of failure in advanced head and neck cancer. Arch Otolaryngol. 1984;110:564–565. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1984.00800350006003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Calhoun KH, Fulmer P, Weiss R, et al. Distant metastases from head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Laryngoscope. 1994;104:1199–1205. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199410000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moody SA, Hirsch BE, Myers EN. Squamous cell carcinoma of the external auditory canal: an evaluation of a staging system. Am J Otol. 2000;21(4):582–588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaifi JT, Gusani NJ, Deshaies I, Kimchi ET, Reed MF, Mahraj RP, et al. Indication and approach to surgical resection of lung metastases. J Surg Oncol. 2010;102:187–195. doi: 10.1002/jso.21596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yano T, Shoji F, Maehara Y. Current status of pulmonary metastasectomy from primary epithelial tumors. Surg Today. 2009;39:91–97. doi: 10.1007/s00595-008-3820-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wedman J, Balm AJ, Hart AA, Loftus BM, Hilgers FJ, Gregor RT, et al. Value of resection of pulmonary metastases in head and neck cancer patients. Head Neck. 1996;18:311–316. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0347(199607/08)18:4<311::AID-HED1>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lefor AT, Bredenberg CE, Kellman RM, Aust JC. Multiple malignancies of the lung and head and neck. Second primary tumor or metastasis? Arch Surg. 1986;121:262–270. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1986.01400030019001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen EE. Role of epidermal growth factor receptor pathway-targeted therapy in patients with recurrent and/or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of head and neck. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2659–2665. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.4577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nibu K, Nakagawa K, Kamata S, Kawabata K, Nakamizo M, Nigauri T, et al. Surgical treatment for pulmonary metastases of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Am J Otolaryngol. 1997;18:391–395. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0709(97)90059-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daiko H, Nagai K, Yoshida J, Nishimura M, Hishida T, Ebihara M, et al. The role of pulmonary resection in tumors metastatic from head and neck carcinoma. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2010;40:639–644. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyq023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shiono S, Kawamura M, Sato T, Okumura S, Nakajima J, Yoshino I, et al. Pulmonary metastasectomy for pulmonary metastases of head and neck carcinomas. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88:856–860. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu D, Labow DM, Dang N, Martini N, Bains M, Burt M, et al. Pulmonary metastasectomy for head and neck cancers. Ann Surg Oncol. 1999;6:572–578. doi: 10.1007/s10434-999-0572-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]