Abstract

To study the use of 1 % isosulfan blue dye in identifying sentinel node, sensitivity and specificity of frozen section and predictive value of sentinel node in predicting other nodal status in the cases of oral cavity and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. 15 patients of oral cavity and oropharyngeal SCC with clinically N0 neck, who required WLE of the primary lesion as well as neck dissection as per recommended treatment protocol, were selected from OPD. 1 % Isosulfan dye was injected peritumorally intraoperatively after the induction of general anaesthesia. Neck dissection was performed and first node taking up the blue dye was identified, dissected, removed and was sent for frozen section. In two of the 15 cases a sentinel node was identified (sensitivity of the technique—13 %). Both the sentinel nodes were positive for presence of metastasis on final histopathology (specificity—100 %). However, five cases had nodal metastasis on final histopathological examination of the neck dissection specimen (sensitivity of sentinel lymph node biopsy—40 %). Frozen section examination had a sensitivity and specificity of 100 %. All data was analyzed using SPSS 16 software. Use of 1 % Isosulfan Dye for identification of sentinel node is a simple and cheap technique, however, it has low sensitivity as compared to the use of triple diagnostic procedure consisting of lymphoscintigraphy, per op gamma probe localization and using isosulfan dye for sentinel node identification. Sentinel lymph node is representative of nodal status and correlates well with the final histopathological examination of the dissected neck nodes.

Keywords: Sentinel node, N0 neck, Isosulfan blue dye, Frozen section, SLNB (sentinel lymph node biopsy)

Introduction

Oral cavity and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas (SCC) have a high metastatic potential and lymph node metastasis is one of the most significant prognostic factor. The presence of a single positive lymph node can reduce the disease free survival at 5 years by 50 % [1–5].

Oral cavity malignancies are associated with 20–40 % risk of occult metastasis which are neither palpable during surgery nor obvious on imaging studies [6–9]. Although there are no universally accepted guidelines, still all patients with clinically N0 neck should undergo neck dissection if risk of occult metastasis is 15–20 %. But up to 80 % of these cN0 patients on histopathology are pN0 and are theoretically over treated [1].

Sentinel lymph node biopsy was first introduced by Cabanas in a case of Squamous cell carcinoma of Penis in 1977 [10]. In head and neck it was first described by Alex and Crag in a case of Supraglottic Carcinoma in 1996 using lymphoscintigraphy [11].

Since then the sentinel node concept has been studied extensively by various surgeons. It is a well established technique for identification of nodal metastasis in cases of early breast cancer and cutaneous malignant melanoma [12]. Its role in head and neck squamous malignancies is being investigated for a long time as the lymphatic drainage in head and neck follows a systematic pattern similar to the breast.

This study was conducted to determine the technical feasibility of identification and localization of sentinel node by means of perilesional injection of 1 % Isosulfan Dye, to determine the sensitivity and specificity of frozen section examination of the sentinel node and to determine whether the histopathologic status of the sentinel node is predictive of the status of the other regional lymph nodes in early squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the oral cavity and oropharynx.

Materials and Methods

The present study was conducted in the Department of Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery at Base Hospital, Delhi Cantt from January 2011 to December 2012. Fifteen patients of SCC of oral cavity and oropharynx with clinically negative neck node and requiring surgery for the primary lesion along with neck dissection as per the recommended treatment protocol were selected from the OPD. All patients with nodal metastasis, past history of neck dissection, radiotherapy, neck injuries, allergy to dye and recurrent disease were excluded from the study.

All patients belonged to 55–66 years of age with 11 males and 4 females with a male:female ratio of 2.7:1. The mean duration of symptoms was 3.4 months. All patients were evaluated in the OPD including a thorough history taking, clinical evaluation and radiological evaluation using CECT face and neck staging the disease. This was followed by punch biopsy and histopathological examination of the primary lesion either in the OPD under local anaesthesia or direct laryngoscopy and biopsy under general anaesthesia in OT.

After obtaining an informed written consent, all patients underwent wide local excision of the primary lesion and neck dissection under GA. Before the start of the surgery the primary site was infiltrated with 2 ml of 1 % isosulfan blue dye 0.5 ml in each margin – anterior, posterior, medial and lateral. Neck dissection was started with a Schobinger incision. Subplatysmal flaps were raised and sentinel node was searched. First node taking up the dye was identified and sent for frozen section examination. The neck dissection was completed in all the cases and specimen sent for histopathological examination in 10 % formalin.

In the post operative period, the frozen section analysis of nodes including sentinel node was compared with the final histopathological report of the neck dissection. In cases where no sentinel node was identified per op, lymph node metastasis was noted as per final histopathology.

All the details were noted in a performa prepared for the study. The data was analyzed using SPSS 16 statistical software to calculate sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV of the technique of sentinel node identification, histopathological correlation of frozen section examination and sentinel lymph node biopsy with the final histopath of the neck dissection. Pearson’s Chi square test was used for comparison and p-values calculated to derive significant or insignificant correlation.

Results

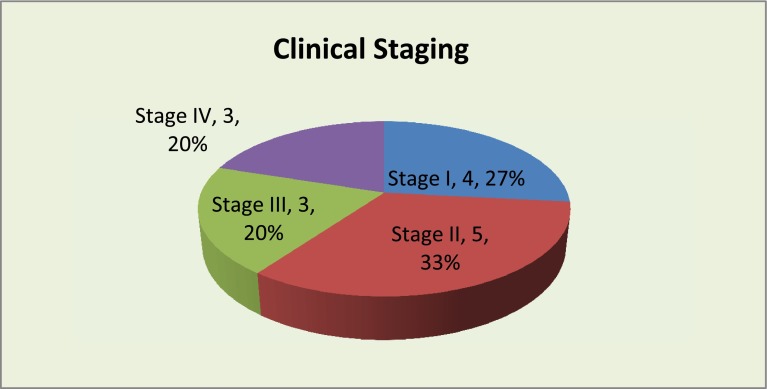

Oral tongue was the most common primary site involved, followed by buccal mucosa (Table 1). The histopathology of primary was Moderately differentiated SCC in eight cases and Well differentiated SCC in seven cases. Majority of the cases belonged to stage I and II constituting 60 % of the total cases (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Site of primary

| Site of primary | Cases | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Tongue | 6 | 40 |

| Tongue extending to BOT, TL Sulcus | 2 | 13 |

| Hard palate | 1 | 7 |

| Floor of mouth | 1 | 7 |

| Lower alveolus | 1 | 7 |

| TL Sulcus | 1 | 7 |

| Buccal Mucosa | 3 | 20 |

| Total | 15 | 100 |

Fig. 1.

Showing the clinical stage of patients at presentation

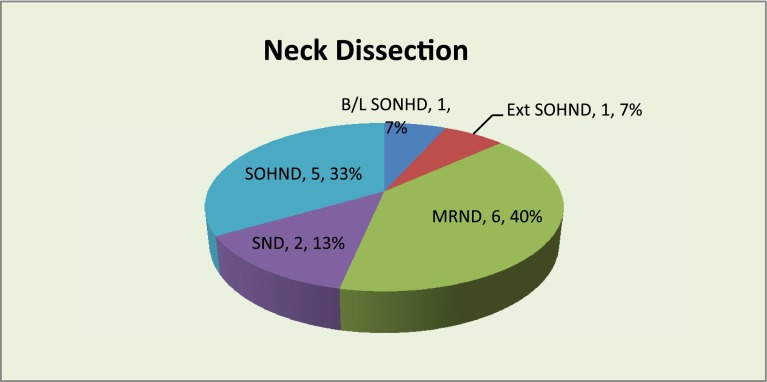

Nine of the fifteen patients had WLE of the primary lesion followed by primary closure where as reconstruction was done in the remaining six cases. All patients underwent neck dissection as per recommended treatment protocol. Nine cases had selective neck dissection either unilateral or bilateral (60 %) and six cases had ipsilateral modified radical neck dissection (40 %) (Fig. 2). Sentinel node was identified in two cases only (13.3 %) at level 1a and level II. In all the other 13 cases no blue stained node was identified (86.7 %).

Fig. 2.

Showing types of neck dissection performed

Frozen section examination was done in 5 cases including two sentinel nodes and in three other cases with intra operative clinically suspicious nodes. Frozen section examination of the sentinel node was positive, whereas, clinically suspicious nodes were negative and it represented the nodal status on final histopathological examination of the neck dissection (Specificity 100 %). PPV and NPV of the frozen section is 100 % in our study. P value is <0.05 indicating significant correlation (Table 2).

Table 2.

Showing frozen section analysis as compared to final histopath

| Frozen section | Final Histopath of neck dissection | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | ||

| Positive | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Negative | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Total | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| Pearson Chi Square | 15 | p value | <0.001 |

| Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV |

| 100 % | 100 % | 100 % | 100 % |

Sensitivity of the sentinel lymph node biopsy has been found to be 40 % and specificity is 100 %. It also has a positive predictive value (PPV) of 100 % and negative predictive value (NPV) of 77 %. P value has been found to be <0.05 which indicates significant correlation (Table 3).

Table 3.

Sentinel node analysis as compared to final histopath

| Sentinel node identified | Final Histopath of neck dissection | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | ||

| Yes | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| No | 3 | 10 | 13 |

| Total | 5 | 10 | 15 |

| Pearson Chi Square | 4.615 | p value | 0.032 |

| Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV |

| 40 % | 100 % | 100 % | 77 % |

Discussion

Since its introduction, sentinel node concept has been studied extensively by various surgeons using blue dye, lymphoscintigraphy and gamma probe. In our study, we used 1 % Isosulfan Blue Dye for identification of sentinel node. A review of pertinent medical literature reveals four similar studies where only dye was used for sentinel node identification.

Pitman et al. performed SLNB in 9 cases of HNSCC with N0 neck and sentinel node could not be identified in any case. They amended the study after initial 9 cases and included patients with clinically positive neck nodes. Still, no blue lymphatic channels or node were visualized after injection of 1 % isosulfan blue dye [13].

Rigual et.al. studied 20 patients of T2N0 oral cavity SCC from 2001 to 2005 and found that only 10 % of the patients had blue stained node [6]. Wiseman et al. studied SLN using 1 % isosulfan dye on seven patients of oral cavity SCC and identified sentinel node in four of the seven cases (sensitivity 57 %) and it successfully predicted the pathological status of other nodes on final histopath in three cases (Specificity 75 %) [5].

Minamikawa et al. performed SLNB in 21 patients of oral cavity SCC with clinically N0 neck [9]. They identified sentinel node in 17 of 21 cases (sensitivity 80.95 %) and it accurately predicted the metastasis in 16 cases (specificity 94 %). Shoaib et al. performed SLNB in six patients of oral cavity and oropharyngeal SCC with N0 neck using Patent blue V dye alone [1]. Sentinel lymph node was identified in four of the six cases (67 %) and they correctly predicted the pathologic status of the neck in only two of the four cases (50 %).

The low sensitivity of the technique used for sentinel node identification can be attributed to the following factors:

The time course for transit from the injection site to the sentinel node is estimated to be 5–15 min for cutaneous melanomas, with lymph node losing their blue color after approximately 20 min due to systemic absorption [14, 15]. Skin flaps elevation for neck dissection takes approximately 5–15 min, thus obviating the window of opportunity to visualize lymphatic channels and thereby lymph node identification.

Faulty technique of injection – for the dye to reach the lymph node basin, 0.5 ml of injection has to be given perilesionally around the primary in each quadrant especially at the draining end. This is to be followed by massage of the primary site to facilitate the flow of dye into the lymphatics.

The volume of the dye that can be injected is limited by the tissue tension, any injection more than 0.5 ml leads to extravasation of the dye into the surrounding tissue.

Lymphatics supplying the mucosal sites are qualitatively different from those of dermal sites, thus dye distribution may be inadequate.

Frozen section examination was done in 5 cases including two cases where the sentinel node was identified. In two cases where sentinel node was identified, frozen section examination showed presence of metastasis and rest three were negative for metastasis. The findings of frozen section were confirmed on final histopathological examination. Both cases where frozen section was positive for metastasis were also positive for metastasis on final histopathological evaluation and were upstaged to N1. Other three cases where frozen was negative, histopathological examination of the neck dissection specimen did not show any metastasis. Thus frozen section examination accurately predicted the status of neck nodes with a specificity of 100 %.

Other studies by Tschopp et al. [16], Barakat et al. [17], Kumar et al. [18] on accuracy of frozen section, found it to have a specificity between 94–100 %.

Sentinel lymph node was identified in two of the five cases showing metastasis on final histopathology, thus having a sensitivity of 40 %. In both these cases, final histopathological examination of the neck dissection specimen showed presence of metastasis in other neck nodes. Thus, sentinel node biopsy had a specificity of 100 % with PPV of 100 % and NPV of 77 %.

In a similar study by Rigual et al. [6], sensitivity and specificity of SLNB in patients of T2N0 oral cavity carcinoma patients were found to be 83 and 100 % respectively. Pitman et al. studied 20 N0 patients and established 95 % sensitivity of the sentinel node procedure and specificity of 100 % in predicting the status of other node on histopathological examination.

Sentinel lymph node biopsy has been done by various other authors using triple technique of pre operative lymphoscintigraphy, intraoperative gamma probe localization and intraoperative peritumoral injection of 1 % isosulfan blue dye.

Ross et al. performed sentinel node biopsy in 48 patients using triple diagnostic procedure including pre operative lymphoscintigraphy, intraoperative gamma probe localization and intraoperative peritumoral injection of 1 % isosulfan blue dye. Sentinel lymph node was identified in 43 of 48 patients thus having a sensitivity of 90 %, and, using the full pathological protocol true sensitivity was found to be 94 % [19].

Shoaib et al. performed sentinel node biopsy using triple technique on 40 patients and sentinel node was identified in 36 of 40 patients (sensitivity of the procedure- 90 %) [1]. Alex et al. performed sentinel node biopsy in eight cases of N0 SCC of head and neck and identified sentinel node in all 8 cases using triple diagnostic procedure. Rigual et al. [6]. studied SLNB in 20 patients using triple diagnostic procedure and identified sentinel node in all 20 cases. Thus the sensitivity of the procedure using triple diagnostic technique is 100 % and all these cases the sentinel node accurately predicted the pathological nodal status in 18 of 20 patients (90 %).

Although, concept of SLNB has been extensively studied since its description by Cabanas in 1977, there are certain important issues to be resolved before it becomes the standard of treatment for early Oral cavity and oropharyngeal SCC as there are inherent pitfalls in the procedure:

-

Routine light microscopy, whether at the time of frozen section examination or after fixation may overlook micrometastasis, thus giving false negative results [7, 20].

This may be improved by step serial sectioning, immunohistochemistry and molecular marker assays (based on reverse transcriptase- polymerase chain reaction technique) but cannot be completely circumvented.

Free soft tissue tumour, defined as a metastatic carcinoma in the soft tissue of the neck with no evidence of a lymph node involvement, is well documented. This cannot be studied by the SLNB [20].

Sentinel lymph node biopsy at two or more level requires general anaesthesia, operating time and cervical dissection, thus offering little benefit over selective neck dissection [7, 21, 22].

Conclusion

To conclude Sentinel node biopsy is a promising tool which is being investigated for detection of occult metastasis in cases early HNSCC. Use of Blue Dye for identification of sentinel node is a simple and cheap technique, however it has low sensitivity as compared to the use of triple diagnostic procedure for identification of sentinel node. Sensitivity can be increased by reducing the time gap between the dye injection and start of biopsy may be to 5 min or a repeat injection of the dye to be done after 20 min. SLNB has a learning curve for the surgeon but intra operative frozen section examination is highly sensitive and specific. It is representative of nodal status, when full pathological protocol is employed and it correlates well with the final histopathological examination of the other nodes. SLNB in HNSCC is not yet established as a diagnostic tool and should be performed within the context of clinical trials.

References

- 1.Shoaib T, Soutar DS, Mac Donald DG, Camilleri IG, Dunaway DG, Gray HW, et al. The accuracy of head and neck carcinoma sentinel lymph node biopsy in the clinically N0 neck. Cancer. 2001;91(11):2077–2083. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010601)91:11<2077::AID-CNCR1235>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shah JP, Anderson PE. Evolving role of modifications in neck dissection for oral squamous carcinoma. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1995;33:3–8. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(95)90077-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vartanian JG, Pontes Everton, Ivan MG, Olimpio DC, Joao GF, et al. Distribution of metastatic lymph nodes in oropharyngeal carcinoma and its implications for the elective treatment of the neck. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129:729–732. doi: 10.1001/archotol.129.7.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones AS, Phillips DE, Helliwell TR, Roland NJ. Occult node metastasis in head and neck squamous carcinoma. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1993;250:446–449. doi: 10.1007/BF00181087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wiseman SM, Loree TR, Hicks WL, Rigual NR. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in SCC of the head and neck: a major advance in staging the N0 neck. ENT-Ear Nose Throat J. 2002;81(3):156–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rigual N, Douglas W, Lamonica D, Wiseman S, Cheney R, Hicks W, Jr, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy: a rational approach for staging T2N0 oral cancer. Laryngoscope. 2005;115(12):2217–2220. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000187870.82699.ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Civantos FJ, Stoeckli SJ, Takes RP, Woolgar JA, De Bree R, Paleri V, et al. What is the role of sentinel node biopsy in the management of oral cancer in 2010? Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;267(6):839–844. doi: 10.1007/s00405-010-1215-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kowalski LP, Sanabria A. Elective neck dissection in oral carcinoma: a critical review of the evidence. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2007;27(3):113–117. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Minamikawa T, Umeda M, Komori T. Reliability of sentinel node biopsy with squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;99(5):532–538. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2004.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cabanas RM. An approach for the treatment of Penile carcinoma. Cancer. 1977;39:456–466. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197702)39:2<456::AID-CNCR2820390214>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alex JC, Krag DN. Gamma-probe-guided resection of radiolabeled primary lymph nodes. Surg Oncol Clin North Am. 1996;5:33–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Civantos FJ, Zitsch RP, Schuller DE, Aggarwal A, Smith RB, Nason R, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy accurately stages the regional lymph nodes for T1–T2 oral squamous cell carcinomas: result of a prospective multi institutional trial. J Clin Oncology. 2010;28(8):1395–1400. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pitman KT, Johnson JT, Brown ML, Myers EN. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:2101–2113. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200212000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pitman KT, Johnson JT, Edington H, Barnes EL, Day R, Wagner RL, et al. Lymphatic mapping with Isosulfan blue dye in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;124:790–793. doi: 10.1001/archotol.124.7.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Don DM, Anzai Y, Lufkin RB, Fu YS, Calcaterra TC. Evaluation of cervical lymph node metastasis in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Laryngoscope. 1995;105:6669–6674. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199507000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tschopp L, Nuyens M, Stauffer E, Krause T, Zbaren P. The value of frozen section analysis of the sentinel node in clinically N0 squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity and oropharynx. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;132(1):99–102. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2004.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barakat FH, Sulaiman I, Sughayer MA (2012) Reliability of frozen section in breast sentinel lymph node examination. Breast Cancer. 2012 Nov 29. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Kumar S, Medeiros F, Dowdy SC, Keeney GL, Bakkum-Gamez JN, Podratz KC, Cliby WA, Mariani A. A prospective assessment of the reliability of frozen section to direct intraoperative decision making in endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;127(3):525–531. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ross G, Shoaib T, Soutar DS, Camilleri IG, Gray HW, Bessent RG, et al. The use of sentinel node biopsy to upstage the clinically N0 neck in head and neck cancer. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;128:1287–1291. doi: 10.1001/archotol.128.11.1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pitman KT, Ferlito A, Devaney KO, Shaha AR, Rinaldo A. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in head and neck cancer. Oral Oncol. 2003;39:343–349. doi: 10.1016/S1368-8375(02)00086-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Calabrese L, Bruschini R, Ansarin M, Giugliano G, De Cicco C, Ionna F, et al. Role of sentinel node biopsy in oral cancer. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2006;26(6):345–349. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coughlin A, Resto VA. Oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma and the clinically N0 neck: the past, present and future of sentinel lymph node biopsy. Curr Oncol Rep. 2010;12(2):129–135. doi: 10.1007/s11912-010-0090-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]