Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate noninvasive and clinically-translatable magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) biomarkers of therapeutic response in the TH-MYCN transgenic mouse model of aggressive, MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma.

Materials and methods

All experiments were performed in accordance with the local ethical review panel, the UK Home Office Animals Scientific Procedures Act 1986 and with the United Kingdom National Cancer Research Institute guidelines for the welfare of animals in cancer research. Multiparametric MRI was performed on abdominal tumors found in the TH-MYCN model. T2-weighted MRI, quantitation of native relaxation times T1 and T2, the relaxation rate R2*, and dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE) MRI were used to monitor tumor response to cyclophosphamide (25mg/kg), the vascular disrupting agent ZD6126 (200mg/kg), or the anti-angiogenic agent cediranib (6mg/kg, daily). Any significant changes in the measured parameters, and in the magnitude of the changes upon treatment between treated and control cohorts, were identified using Student’s 2-tailed paired and unpaired t-test respectively, with a 5% level of significance.

Results

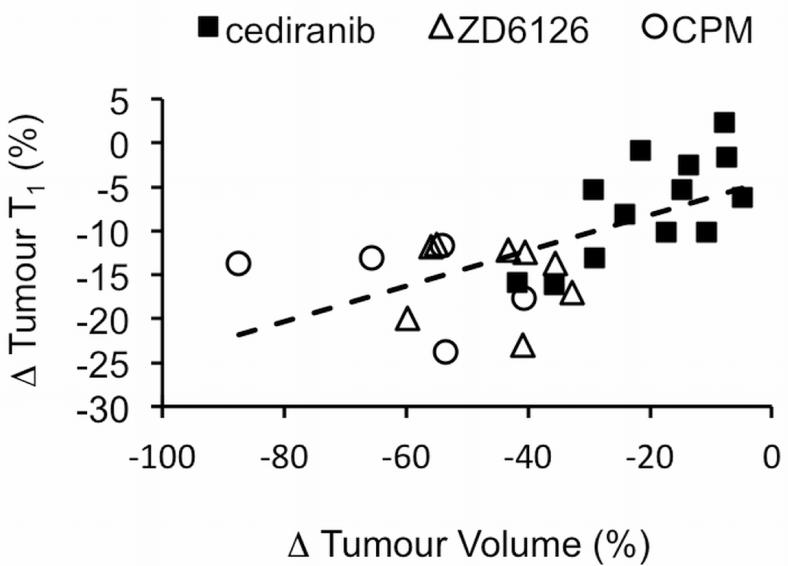

Treatment with cyclophosphamide or cediranib induced a 54% and 20% reduction in tumour volume at 48 hours respectively (p<0.005 and p<0.005, p<0.005 and p<0.005 versus control). Treatment with ZD6126 induced a 45% reduction in mean tumor volume 24 hours after treatment (p<0.005, p<0.005 versus control). The anti-tumor activity of cyclophosphamide, cediranib and ZD6126 was consistently associated with a decrease in tumor T1 (p<0.005, p<0.005 and p<0.005, respectively, p<0.005, p<0.005 and p<0.005 versus control respectively) and with a correlation between therapy-induced changes in native T1 and changes in tumor volume (r = 0.56, p < 0.005). Tumor response to cediranib was also associated with a decrease in the DCE MRI derived volume transfer constant Ktrans (p=0.07, p<0.05 versus control) and enhancing fraction (p<0.05, p<0.01 versus control), and an increase in R2* (p<0.005, p<0.05 versus control).

Conclusions

The T1 relaxation time is a robust noninvasive imaging biomarker of response to therapy in tumors in TH-MYCN mice, which emulate high-risk neuroblastoma in children. T1 measurements can be readily implemented on clinical MR systems, and should be investigated in translational clinical trials of new targeted therapies for pediatric neuroblastoma.

Keywords: T1, MRI, Biomarker, Neuroblastoma, Chemotherapy

Introduction

Neuroblastoma is the most common extracranial solid tumor in childhood, and the most frequently diagnosed neoplasm during infancy. Primary tumors arise from sympathoadrenal derivatives of neural crest origin, explaining the typical location of these lesions in adrenal medulla (30%), peri-adrenal and para-spinal sympathetic ganglia (1). The clinical presentation of neuroblastoma is uniquely varied, in part reflecting differences in the neuronal maturation status of these tumors, with virtually incurable, undifferentiated tumors occurring in older children, and almost universally curable, regressing tumors restricted to very young children (<18mo). Although low and intermediate risk neuroblastoma is in general highly curable using conventional treatment approaches, neuroblastoma still accounts for 15% of all pediatric oncology deaths, and the long-term survival for the subset of children with high-risk tumors remains less than 40%, highlighting the crucial need for novel therapeutic strategies against high-risk childhood disease.

The poor clinical outcome and aggressive tumor phenotype of high-risk neuroblastoma strongly correlates with amplification of the proto-oncogene MYCN and enhanced tumor angiogenesis, suggesting both MYCN-targeted therapeutics and anti-vascular agents as attractive additions to the currently weak portfolio of effective drugs (2). However, the clinical development of novel targeted therapies in pediatric oncology is hindered by regulatory, economic, ethical and technical issues (3, 4).

Noninvasive imaging strategies, and their derived biomarkers of therapeutic efficacy, are attractive as they can facilitate and accelerate clinical drug development (5). In this study, a multi-parametric magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed to characterize the therapeutic response of the TH-MYCN genetically-engineered murine (GEM) model of neuroblastoma, to three clinically relevant classes of anti-cancer agents for the treatment of this childhood disease. TH-MYCN mice develop tumors that mirror the major pathophysiological characteristics of pediatric neuroblastoma with MYCN-amplification (6), as well as response to conventional front-line chemotherapeutics (7, 8). This GEM model thus provides a biologically analogous platform for the pre-clinical development and evaluation of novel therapeutics against neuroblastoma (9, 10), and the robust evaluation of associated noninvasive imaging biomarkers of response to treatment. The purpose of this study was to evaluate noninvasive and clinically-translatable MRI biomarkers of therapeutic response in the TH-MYCN transgenic mouse model of aggressive, MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma.

Materials and Methods

The studies reported here were carried out between July 2009 and April 2012. ZD6126 and cediranib were obtained through material transfer agreement with Angiogene Pharmaceuticals Ltd. and AstraZeneca, respectively. All the data presented in this study are owned and controlled by the authors and The Institute of Cancer Research.

Animal model

All experiments were performed in accordance with the local ethical review panel, the UK Home Office Animals Scientific Procedures Act 1986 and with the United Kingdom National Cancer Research Institute guidelines for the welfare of animals in cancer research (11), TH-MYCN mice with tumors were initially identified by palpation.

Drug treatment and imaging schedule

Four cohorts of TH-MYCN mice (n=52) received drug treatment and were evaluated using MRI according to the following schedules:

Cyclophosphamide (CPM, Baxter Healthcare Ltd., Norfolk, UK) is an ubiquitous component of most current conventional chemotherapy regimens administered for high-risk neuroblastoma. CPM was administered as a single i.p. 25mg/kg dose. MRI was performed prior to and 48h after treatment with CPM (n=5) or vehicle (n=5).

The extent of functional vasculature is an important determinant of the survival of children with neuroblastoma. Anti-vascular agents thus represent a promising class of therapeutic agents for phase I evaluation in pediatric neuroblastoma. TH-MYCN mice were challenged with the vascular disrupting agent, ZD6126, a phosphate prodrug of N-acetylcolchinol, which inhibits microtubule polymerization (12, 13), ZD6126 (N-acetylcolchinol-O-phosphate, Angiogene Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Oxford, UK) was formulated in 20% of 5% sodium carbonate and 80% phosphate-buffered saline and was administered as a single i.p. 200mg/kg dose. MRI was performed prior to and 24h after treatment with ZD6126 (n=8) or vehicle (n=8), with 6 animals of each cohort undergoing DCE-MRI.

The anti-angiogenic agent cediranib (AstraZeneca, Alderley Park, UK) is a potent inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR) tyrosine kinases currently in early phase clinical evaluation for the treatment of other pediatric cancers (14). Cediranib has been shown to cause tumor growth delay in neuroblastoma xenografts (15, 16), highlighting its potential for the treatment of neuroblastoma. Cediranib was dissolved in 1% Tween and administered daily at a dose of 6mg/kg p.o. MRI was performed prior to and 48h after initiating treatment (24h following the second dose). MRI was performed prior to and 48h after beginning of treatment with cediranib (n=11) or vehicle (n=11) with 7 animals of each cohort undergoing DCE-MRI.

Cediranib was administered as in cohort 3 (n=4), but with imaging performed prior to, 48h and 7 days after initiating treatment.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

All the 1H MRI studies were performed by Y.J., with 8 years of experience in preclinical imaging, on a 7T Bruker horizontal bore micro-imaging system (Bruker Instruments, Ettlingen, Germany) using a 3cm birdcage coil. Anesthesia was induced by an intraperitoneal 0.1ml injection of a combination of fentanyl citrate (0.315mg/ml) plus fluanisone (10mg/ml) (Hypnorm, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Oxford, UK) and midazolam (5mg/ml) (Roche, Welwyn Garden City, UK) and water (1:1:2). For animals undergoing dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE) MRI, a lateral tail vein was cannulated to enable remote administration of Gd-DTPA contrast medium (Magnevist, Schering, Berlin, Germany). All data were fitted pixelwise using in-house software (ImageView, working under IDL, ITT, Boulder, Colorado, USA) and reviewed by Y.J, S.P.R, who has 22 years of experience in preclinical MRI and D-M.K, who has 20 years of experience as a clinical radiologist.

For all study cohorts, anatomical T2-weighted coronal and transverse images were acquired from twenty contiguous 1mm-thick coronal slices through the mouse abdomen, using a rapid acquisition with refocused echoes (RARE) sequence with 4 averages of 128 phase encoding steps over a 3×3 cm field of view, two echo times (TE) of 36 and 132 ms, a repetition time (TR) of 4.5s and a RARE factor of 8. These images were used for determining tumor volumes and for the planning of the multi-parametric functional MR assessment, which included an optimization of the local field homogeneity and the following:

The baseline transverse relaxation rate R2* (s−1), a parameter sensitive to the concentration of paramagnetic species, principally deoxyhemoglobin, was quantified using a multi-gradient echo (MGE) sequence, acquired from three 1mm-thick transverse slices through each tumor, using 8 averages of 128 phase encoding steps over a 3×3cm field of view, and an acquisition time of 3min 20s. Images were acquired using 8 echoes spaced 3ms apart, an initial echo time of 6ms, a flip angle α=45° and a repetition time of 200ms, and were fitted using a robust Bayesian approach that provided estimates of R2* (17). Quantitation of R2* reflects both tissue blood flow and hypoxia, and faster R2* values have been observed in tumors compared with normal tissues.

The native spin-lattice relaxation time T1 (ms) and transverse relaxation time T2 (ms) of tumors were quantified. These parameters are sensitive to the ratio between tissue free and bound water, with tumors returning longer T1 and T2 relaxation times compared with normal tissues. These images were acquired from a single transverse 1mm slice (the central slice planned for the MGE sequence) using a rapid inversion recovery (IR) true fast imaging with steady-state precession (trueFISP) sequence, with 8 averages of a matrix size of 128×96 over a 3×3 cm field of view, and an acquisition time of 10min 40s. Images were acquired using an echo time of 1.2ms, a TR of 2.4ms and 50 inversion times spaced 28ms apart, an initial inversion time of 25ms, a flip angle α=60° and a total scan repetition time of 10s. IR-trueFISP data were fitted with a robust Bayesian approach, which also utilized the dual relaxation rate sensitivity of the IR-trueFISP sequence, providing estimates of native T1 and T2 relaxation times.

DCE MRI was incorporated into the studies investigating the response of tumors in TH-MYCN mice to ZD6126 or cediranib (i.e. cohorts 2, 3). DCE MRI affords quantitative biomarkers, which reflect both vascular permeability and perfusion. DCE MRI was performed using an inversion recovery (IR)-trueFISP sequence, with 2 averages, an echo time of 2ms, a TR of 4ms and 8 inversion times spaced 130ms apart, an initial inversion time of 130ms, a flip angle α=60° and a total scan repetition time of 10s, giving a temporal resolution of 20s and, by acquiring 60 dynamic scans, a total acquisition time of 20min. A bolus of 0.1mmol/kg Gd-DTPA was administered using a power injector 3min after starting the DCE MRI acquisition (18). DCE MRI data were analyzed incorporating the Tofts and Kermode pharmacokinetic model, from which the initial area under the gadolinium curve from 0 to 60s (IAUGC60, mM Gd.min), the volume transfer constant (Ktrans, min−1), the extravascular extracellular leakage space (Ve), and the ratio of enhancing to total tumor volume (enhancing fraction, EF), were estimated.

Histological Assessment

Formalin fixed paraffin embedded sections from control and treated tumors were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and visualized under light microscopy for the assessment of necrosis. The extent of functional vasculature was assessed using the perfusion marker Hoechst 33342, and the degree of hypoxia from pimonidazole adduct formation, both quantified (%) as previously described (18).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, USA). The mean of median values for all the quantitative MRI parameters, the mean values for tumor volume, and the fluorescent area fractions were used for statistical analysis. All the MRI parameters and therapy-induced relative changes in these parameters, were assumed to be normally distributed, which was confirmed using the D’Agostino-Pearson omnibus K2 normality test (19). Unless otherwise stated, any significant changes in absolute tumor volume, and quantitative MR parameters prior to and following treatment, were identified using Student’s 2-tailed paired t-test, with a 5% level of significance. Relative changes in these parameters were expressed as a percentage of the pre-treatment value, and for each treatment schedule, any significant differences between treated and control cohorts identified using Student’s 2-tailed unpaired t-test, with a 5% level of significance. Further statistical analysis using the Bonferroni correction (n=3) was performed on the therapy-induced changes in native parameters T1, T2 and R2* (paired test), and the magnitude of these changes compared to control (unpaired test) with a 0% level of significance. Significant correlation between the relative change in T1 and tumor volume (expressed as (T1post-treatment - T1pre-treatment)/T1pre-treatment) upon therapy were determined by using linear regression analysis, confirmed by using the robust regression and outlier removal approach (20).

Results

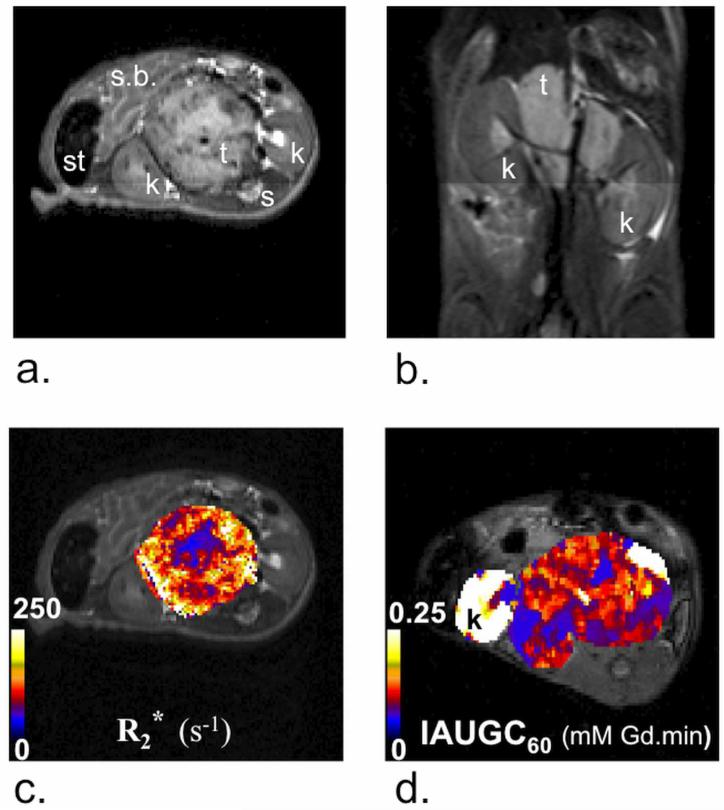

For TH-MYCN mice with abdominal tumors, anatomical T2-weighted MRI revealed solid masses (1449 ± 134mm3, mean ± 1 s.e.m, n=43) within the retroperitoneum in peri-renal and para-spinal abdominal regions, consistent with the typical clinical distribution and radiological presentation of human neuroblastoma (Figure 1a&b) (21, 22). The relatively fast and heterogeneous distribution of R2*, and the clear parenchymal signal enhancement following injection Gd-DTPA contrast medium, typically across the whole tumor, indicated that the tumors in the TH-MYCN mice are well-vascularized, and consistent with the vascular phenotype of childhood neuroblastoma with MYCN-gene amplification (Figure 1c&d) (2). Findings from the specific cohorts are as below.

Figure 1.

Anatomical a) transverse and b) coronal T2-weighted magnetic resonance (MR) images from two representative TH-MYCN mice presenting with abdominal neuroblastoma. Tumors typically grew in the proximity of the kidneys (k) and the spine (s), causing displacement of major abdominal organs, including the kidneys, small-bowel (s.b.) and stomach (st). Parametric c) R2* and d) IAUGC60 maps calculated from tumors of TH-MYCN mice, the latter windowed to show enhancement across the tumor (hence the saturated signal from the proximal kidneys).

Tumor response to cyclophosphamide

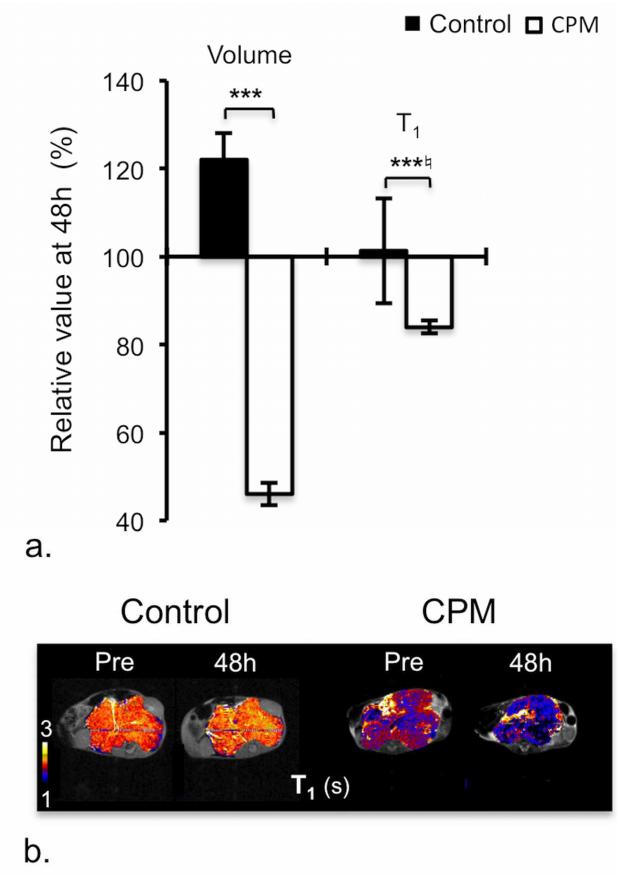

Treatment with a single 25mg/kg dose of CPM resulted in significant and consistent anti-tumor activity after 48h, and was associated with a significant and consistent reduction in native T1 (Table 1, Figure 2a&b). The volumetric imaging response observed herein is consistent with previous studies in the TH-MYCN model, where CPM was shown to have a significant anti-tumor activity mediated by an increase in apoptosis and a significant reduction in proliferation (7).

Table 1. Response of TH-MYCN model of neuroblastoma to cyclophosphamide.

Summary of tumor volume and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) parameters quantified prior to and 48h following treatment of tumor-bearing TH-MYCN mice with 25mg/kg cyclophosphamide (CPM) or vehicle.

| Control | CPM | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Parameter | Pre | 48h | Pre | 48h |

| Volume (mm3) | 1980 ± 227 | 2381 ± 240 (0.007) | 2288 ± 497 | 896 ± 363 (0.005) |

| T1 (ms) | 1944 ± 58 | 1961 ± 23 (0.71) | 1853 ± 76 | 1555 ± 90 (0.003) |

| T2 (ms) | 59 ± 1 | 64 ± 3 (0.16) | 56 ± 4 | 57 ± 4 (0.97) |

| R2* (s−1) | 132 ± 9 | 131 ± 13 (0.98) | 107 ± 9 | 123 ± 13 (0.14) |

Data are presented as mean ± 1 standard error of the mean (n=5,5). Numbers in parentheses show p-value (Student’s 2-tailed paired t-test).

Figure 2.

Response of TH-MYCN model of neuroblastoma to cyclophosphamide (CPM). a) Relative changes in tumor volume and native T1 over 48h in tumor-bearing TH-MYCN mice following treatment with vehicle or 25mg/kg CPM. Normalized data are presented as mean ± 1 standard error of the mean (n=5), with any significant differences between control and CPM-treated cohort indicated (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.005, Student’s 2-tailed unpaired t-test, and *♮p<0.02, **♮p<0.003, ***♮p<0.0002, Student’s 2-tailed unpaired t-test with a Bonferroni correction (n=3)). b) Parametric T1 maps of tumor-bearing TH-MYCN mice acquired prior to and 48h following treatment with vehicle or 25mg/kg CPM.

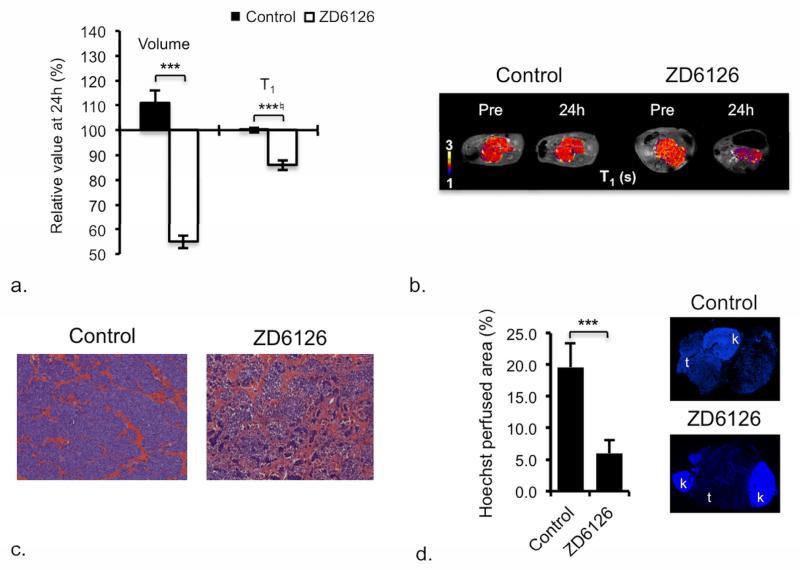

Tumor response to ZD6126

In the TH-MYCN model, ZD6126 caused acute hemorrhagic necrosis, with rapid and highly significant tumor regression and a highly significant and consistent reduction in native T1 (Table 2, Figure 3a-c). The dense, functionally perfused vasculature of the tumors of control mice, revealed by the extensive uptake of Hoechst 33342, was significantly reduced in the tumors of ZD6126-treated mice (Figure 3d). Despite the clear effect on the functional vasculature, no significant difference in either R2*, or DCE MRI-derived parameters, was found between the ZD6126-treated and control tumors. ZD6126 induces massive central hemorrhagic necrosis in a wide range of pre-clinical tumor models, but with only modest tumor growth inhibition 24h after treatment, which relates to the persistence of viable tissue at the tumor rim, evading therapy and re-initiating tumor growth (12, 13, 23). The profound anti-tumor activity of ZD6126 against the TH-MYCN model determined herein is in stark contrast, and corroborates the significant in vivo cytotoxic activity of colchicine and other inhibitors of tubulin polymerization against neuroblastoma, which, like ZD6126, interact with the colchicine-binding site of tubulin (24). One such agent, ABT-751, is currently being evaluated in clinical trials for neuroblastoma (25). The anti-tumor activity of ZD6126 is thus most likely a consequence of direct cytotoxic effects on the neuroblasts, combined with disruption of blood vessels.

Table 2. Response of TH-MYCN model of neuroblastoma to anti-vascular therapy.

Summary of tumor volume and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) parameters determined prior to and 24h following treatment of tumor-bearing THMYCN mice with a single dose of 200mg/kg ZD6126 or vehicle, or prior to and 48h following daily treatment with 6mg/kg cediranib or vehicle.

| ZD6126 | cediranib | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

| Control | Treated | Control | Treated | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| Parameter | Pre | 24h | Pre | 24h | Pre | 48h | Pre | 48h |

| Native relaxation times/rates 1 | ||||||||

| Volume (mm3) | 867 ± 181 | 977 ± 222 (0.06) | 944 ± 183 | 593 ± 115 (0.0001) | 1218 ± 217 | 1546 ± 254 (0.0002) | 1297 ± 215 | 1033 ± 174 (0.001) |

| T1 (ms) | 1846 ± 29 | 1843 ± 28 (0.86) | 1867 ± 32 | 1607 ± 31 (0.0001) | 1878 ± 26 | 1943 ± 43 (0.20) | 1807 ± 21 | 1667 ± 35 (0.00003) |

| T2 (ms) | 63 ± 4 | 60 ± 2 (0.40) | 77 ± 12 | 56 ± 3 (0.12) | 71 ± 9 | 64 ± 4 (0.49) | 66 ± 6 | 53 ± 3 (0.06) |

| R2* (s−1) | 101 ± 7 | 98 ± 6 (0.43) | 106 ± 7 | 123 ± 13 (0.25) | 114 ± 7 | 114 ± 8 (0.29) | 106 ± 6 | 131 ± 9 (0.004) |

| DCE MRI parameters 2 | ||||||||

| Volume (mm3) | 1214 ± 346 | 1389 ± 423 (0.06) | 966 ± 184 | 533 ± 113 (0.003) | 1492 ± 418 | 1782 ± 483 (0.006) | 1849 ± 220 | 1486 ± 173 (0.02) |

| IAUGC60 (mM Gd.min) | 0.043 ± 0.008 | 0.093 ± 0.016 (0.07) | 0.032 ± 0.005 | 0.052 ± 0.015 (0.25) | 0.032 ± 0.010 | 0.061± 0.02 (0.22) | 0.022 ± 0.004 | 0.017 ± 0.006 (0.37) |

| Ktrans (min−1) | 0.072 ± 0.018 | 0.116± 0.015 (0.12) | 0.057 ± 0.016 | 0.062 ± 0.023 (0.88) | 0.059 ± 0.018 | 0.073 ± 0.02 (0.25) | 0.027 ± 0.007 | 0.013 ± 0.004 (0.07) |

| Ve | 0.073± 0.011 | 0.1 ± 0.005 (0.09) | 0.056 ± 0.021 | 0.120 ± 0.024 (0.03) | 0.062 ± 0.013 | 0.078 ± 0.012 (0.09) | 0.058 ± 0.005 | 0.082± 0.022 (0.25) |

| EF (%) | 98.3 ± 0.5 | 98.9 ± 0.4 (0.43) | 90.8 ± 6.1 | 92.0 ± 5.7 (0.61) | 94.1 ± 2.7 | 96.2 ± 1.5 (0.33) | 93.7± 1.4 | 84.7± 4 (0.04 |

Data are presented as mean ± 1 standard error of the mean

(n=8,8 for study with ZD6126 and n=11,11 for study with cediranib,

n=6,6 for study with ZD6126 and n=7,7 for study with cediranib). Numbers in parentheses show p-value (Student’s 2-tailed paired t-test).

Figure 3.

Response of TH-MYCN model of neuroblastoma to ZD6126. a) Relative changes in tumor volume and native T1 over 24h in tumor-bearing TH-MYCN mice following treatment with vehicle or 200mg/kg ZD6126. Normalized data are presented as mean ± 1 standard error of the mean (n=8 for volume, T1, T2, R2*, n=6 for dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE) MRI parameters), with any significant differences between vehicle and ZD6126-treated cohort indicated (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.005, Student’s 2-tailed unpaired t-test, and *♮p<0.02, **♮p<0.003, ***♮p<0.0002, Student’s 2-tailed unpaired t-test with a bonferroni correction (n=3)). b) Parametric T1 maps of tumor-bearing TH-MYCN mice acquired prior to and 24h following treatment with vehicle or 200mg/kg ZD6126. c) Microscopic images (×100) from hematoxylin and eosin stained sections showing extensive hemorrhagic necrosis in tumors of TH-MYCN mice 24h after treatment with 200mg/kg ZD6126. d) Composite fluorescence images of uptake of the perfusion marker Hoechst 33342 into the tumor and kidneys of TH-MYCN mice, demonstrate reduced vascular perfusion (expressed as Hoechst perfused area) in tumors of TH-MYCN mice, 24h after treatment with 200mg/kg ZD6126 compared with tumor of control TH-MYCN mice.

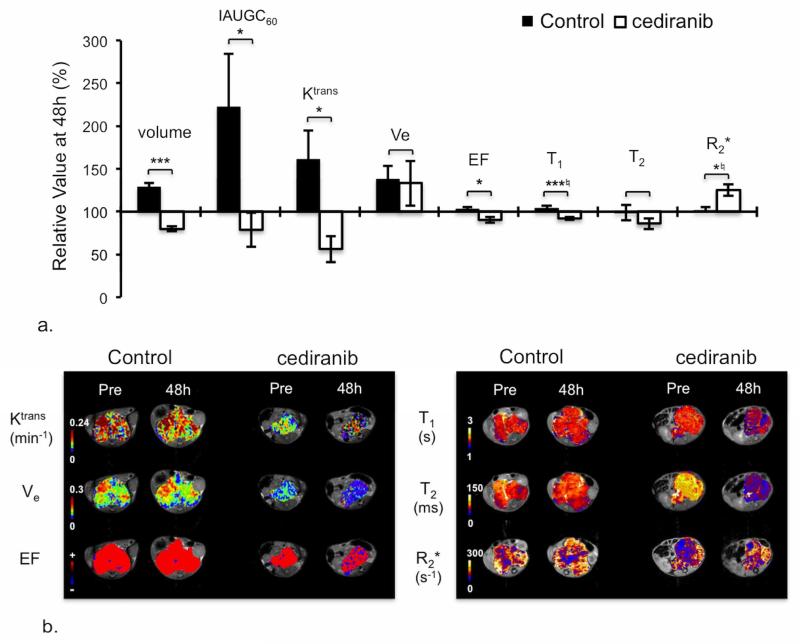

Tumor response to cediranib

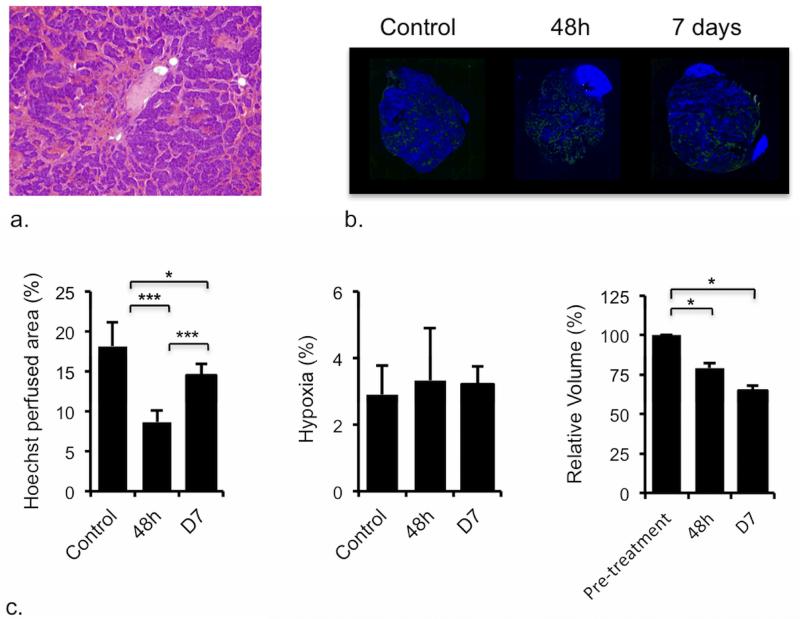

Cediranib exhibited significant anti-tumor activity against the TH-MYCN model over 48h, which was also associated with a consistent and highly significant reduction in native T1 (Table 2, Figure 4a&b). The significant reduction in IAUGC60, Ktrans and EF is consistent with a cediranib-induced reduction in tumor vascular permeability and perfusion (Table 2, Figure 4a&b). Cediranib anti-tumor activity was associated with vascular thrombosis at 48h in the TH-MYCN model (Figure 5a), leading to a decrease in vascular perfusion (Figure 5b&c), which accounts for the significant increase in the tumor transverse relaxation R2* determined 48h post treatment. Downregulation of VEGFR downstream pathways (Supplementary Method and Figure 1) was confirmed at 48h post-treatment and sustained following a week of continued daily dosing with cediranib. Anti-tumor activity of cediranib was also sustained at 7 days (Figure 5c). However, the significant increase in Hoechst 33342 uptake at 7 days compared to that at 48h suggested a recovery of the functional tumor vasculature despite the mice still being treated. The degree of baseline hypoxia was negligible, and was not significantly different in the tumors of cediranib treated TH-MYCN mice (Figure 5c).

Figure 4.

MRI response of TH-MYCN model of neuroblastoma to cediranib. a) Relative changes in tumor volume and dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE) MRI-derived parameters: IAUGC60, Ktrans, Ve, enhancing fraction (EF), and native T1, T2 and R2*, over 48h in tumor-bearing TH-MYCN mice, following daily treatment with either vehicle or 6mg/kg cediranib. Normalized data are presented as mean ± 1 standard error of the mean (n=11 for volume, T1, T2, R2*, n=7 for DCE MRI parameters), with any significant differences between control and cediranib-treated cohort indicated (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.005, Student’s 2-tailed unpaired t-test, and *♮p<0.02, **♮p<0.003, ***♮p<0.0002, Student’s 2-tailed unpaired t-test with a Bonferroni correction (n=3)). b) Parametric Ktrans, Ve, EF, native T1, T2 and R2* maps of tumor-bearing TH-MYCN mice acquired prior to and 48h after the beginning of daily treatment with either vehicle or 6mg/kg cediranib.

Figure 5.

Pathological response of TH-MYCN model of neuroblastoma to cediranib. a) Microscopic image (×40) from a hematoxylin and eosin stained section prepared from a tumor of a TH-MYCN mouse, 48h after treatment with cediranib, showing increased vascular thrombosis (c.f. control tumor in Figure 2c). The frequency of vascular thrombosis was significantly greater in sections from the cediranib tumors compared with control (p=0.03, χ2-test, n=4 treated, n=7 control). b) Composite fluorescence images of uptake of the perfusion marker Hoechst 33342 (blue), and pimonidazole adduct formation (green) into the tumor and kidneys of TH-MYCN mice, demonstrating reduced vascular perfusion (expressed as Hoechst perfused area) in tumors of TH-MYCN mice, 48h and 7 days after treatment with a daily dose of 6mg/kg cediranib, compared with tumors of control TH-MYCN mice (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.005, Student’s 2-tailed unpaired t-test). The degree of tumor hypoxia was negligible, and no differences in hypoxia between treated and control tumors were detected. Tumor volumes decreased over 48h in tumor-bearing TH-MYCN mice, an effect sustained at 7 days following daily treatment with 6mg/kg cediranib. (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.005, Student’s 2-tailed paired t-test).

Collectively, efficacious treatment with CPM, ZD6126, or cediranib was consistently associated with a highly significant decrease in tumor T1 in the TH-MYCN model. The reduction in T1 also significantly correlated with the therapy-induced reduction in tumor volume (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Correlation between changes in native T1 (% of pretreatment value) and changes in tumour volume following treatment with either cyclophosphamide (CPM), ZD6126 or cediranib. r = 0.58, p < 0.002.

Discussion

In the current study we identified a reduction in native T1 relaxation time as a noninvasive imaging biomarker that is associated with successful therapy in the TH-MYCN model of high-risk neuroblastoma, and an increase in R2* relaxation rate as a specific biomarker of response to cediranib therapy. With a sensitivity of 96% and a specificity of 75% native T1 provides an attractive biomarker of response to therapy in the TH-MYCN model. This study also demonstrated that both intrinsic susceptibility- and DCE- MRI can be used to assess the anti-angiogenic activity of cediranib in the TH-MYCN model of neuroblastoma through the increase in R2* and reduction in Ktrans, IAUGC60 and EF respectively.

DCE MRI, using low molecular weight gadolinium contrast agents, is minimally invasive and is now widely used in adult clinical trial investigations to assess vascular-disrupting and anti-angiogenic therapies (5, 26, 27). However, the implementation of DCE MRI protocols in young children remains challenging, requiring close co-operation between the oncologist, radiologist, technician, physicist and anesthetist, and may thus appear disconcerting for the parents/guardians who ultimately must give their consent. In contrast, the quantitation of tumor imaging biomarkers, such as native T1 and R2*, is rapid and totally noninvasive, and can be easily incorporated into existing clinical imaging protocols for evaluation in future clinical trials of targeted agents against neuroblastoma. Once clinically validated, such measurements will simplify and shorten scanning sessions, and ultimately facilitate the early phase of clinical development of these novel therapies.

This study builds on pre-clinical data showing that fractional changes in native T1 correlated with eventual change in tumor volume in a wide range of chemosensitive xenograft models following treatment with five different drugs (28). Furthermore, a recent clinical study reported progressive reductions in native tumor T1 in patients with colorectal cancer metastasis following treatment with bevacizumab, demonstrating that the consistent but relatively small changes in T1 with therapy are detectable at clinical field strengths (29). Physiologically, a reduction in tumor T1 can be the result of the release of paramagnetic species following therapy-induced damage to erythrocytes, and/or caused by therapy-induced perturbation in the ratio of free to bound water in the tissue. Such perturbations can result from the resolution of edema, which has been observed in cediranib-treated patients with glioblastoma (30), cell death-mediated increases in macromolecules into the extravascular extracellular space (28), and more generally any therapy induced remodelling of water compartmentalization in the tumor (31).

Intrinsic susceptibility MRI quantitation of R2*, sensitive to changes in paramagnetic deoxyhemoglobin, is being exploited as an emerging imaging biomarker of response to vascular targeted therapies, including cediranib therapy (32-34). Accordingly, the thrombosis observed following cediranib therapy and aggregation of deoxygenated erythrocytes (rouleaux) within the vascular compartment of tumors in the TH-MYCN mice corroborates the significant increase in R2*.

This study suffers from several limitations. Childhood neuroblastoma is considered a chemosensitive tumor, and this clinical hallmark is emulated by the TH-MYCN model (1). Noninvasive imaging biomarkers of therapy response are attractive and sought for their ability to detect early therapy-induced changes in tumor metabolism and physiology that precedes any volume response (35). The dramatic and rapid reduction in tumor volume observed in the TH-MYCN mice following treatment renders the interpretation of imaging biomarkers interrogated in this study challenging. The unprecedented tumor volume reduction observed at 24 hours following treatment with ZD6126 would conceal the physiological events to which intrinsic susceptibility- and DCE-MRI are sensitive to: decrease in deoxyhemoglobin concentration through hemoglobin denaturation and a reduction in perfusion/permeability, which resulted in significant decreases in R2* and Ktrans respectively reported in other models treated with ZD6126 (32, 36). Also, the low temporal resolution of our DCE-MRI protocol only provides an estimate of Ktrans, which may have lowered the sensitivity of Ktrans towards the decrease in vascular permeability/perfusion. However Ktrans, and the model-free parameters IAUGC60 and EF, were all sensitive to similar decreases in tumor hemodynamics in response to cediranib. This supports the inference that the considerable decrease in tumor volume induced by ZD6126 is the most probable cause for the apparent insensitivity of DCE-MRI biomarkers to ZD6126 treatment (37, 38). Conversely the same reduction of tumor volume may have enhanced the sensitivity of T1 for therapy response.

Future directions

This study identified a potential risk of relapse of the vasculature during cediranib therapy in the TH-MYCN model, which should be further investigated since cediranib is currently being evaluated in children and adolescents with refractory solid tumors (14). Finally, diffusion-weighted MRI (DWI), and its associated biomarker, the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC), should also be of significant interest, given the sensitivity of ADC to therapy–induced cell death (39, 40), and potentially incorporated into clinical pediatric imaging protocols, alongside measurements of native T1 and R2*.

Supplementary Material

Advances in Knowledge.

The TH-MYCN transgenic mouse model of neuroblastoma simultates the clinical disease in terms of its radiological appearance assessed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Quantification of the native T1 relaxation time provides a noninvasive imaging biomarker for chemotherapy-mediated cell death in the TH-MYCN model of neuroblastoma.

Quantification of the R2* relaxation rate provides a noninvasive imaging biomarker of response to anti-angiogenic therapy with cediranib in the TH-MYCN model of neuroblastoma.

Implications for Patient Care.

The use of T1 relaxation time as an early response marker will accelerate the preclinical evaluation of novel targeted therapeutics in the TH-MYCN transgenic mouse model for the treatment of childhood neuroblastoma.

Once proven clinically useful, the rapid and noninvasive quantification of native magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) parameters such as T1 and R2* will simplify imaging embedded clinical trials and accelerate the clinical development of novel therapeutics for the treatment of pediatric neuroblastoma.

Summary Statement.

In the current study we identified a reduction in native T1 relaxation time as a noninvasive imaging biomarker that is associated with successful therapy in the TH-MYCN model of high-risk neuroblastoma, and an increase in R2* relaxation rate as a specific biomarker of response to cediranib therapy.

Acknowledgements

Peter Davis (Angiogene Pharmaceuticals Ltd) for the supply of ZD6126, AstraZeneca for the supply of cediranib and Juliane Jürgensmeier (AstraZeneca) for her helpful input.

Funding information: We acknowledge the support received for The Institute of Cancer Research CR-UK and EPSRC Cancer Imaging Centre, in association with the MRC and Department of Health (England) grants C1060/A10334, CR-UK project grant C16412/A6269, C36952/A11924, NHS funding to the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre, AstraZeneca, The Wellcome Trust grant #091763Z/10/Z, and MRC grant G0700017. Pre-clinical development of the TH-MYCN model was funded by grants from The Neuroblastoma Society, the SPARKS charity, the Christopher’s Smile charity and MRC NC3R grant #G1000121/94513

References

- 1.Maris JM. Recent advances in neuroblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(23):2202–2211. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meitar D, Crawford SE, Rademaker AW, Cohn SL. Tumor angiogenesis correlates with metastatic disease, N-myc amplification, and poor outcome in human neuroblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14(2):405–414. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.2.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balis FM. Clinical trials in childhood cancers. Oncologist. 2000;5(3):xii–xiii. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.5-3-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moreno L, Chesler L, Hargrave D, Eccles SA, Pearson ADJ. Preclinical drug development for childhood cancer. Expert Opin Drug Dis. 2011;6(1):49–64. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2011.537652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Connor JP, Jackson A, Asselin MC, et al. Quantitative imaging biomarkers in the clinical development of targeted therapeutics: current and future perspectives. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(8):766–776. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70196-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weiss WA, Aldape K, Mohapatra G, Feuerstein BG, Bishop JM. Targeted expression of MYCN causes neuroblastoma in transgenic mice. Embo J. 1997;16(11):2985–2995. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.11.2985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chesler L, Goldenberg DD, Collins R, et al. Chemotherapy-induced apoptosis in a transgenic model of neuroblastoma proceeds through p53 induction. Neoplasia. 2008;10(11):1268–1274. doi: 10.1593/neo.08778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hogarty MD, Norris MD, Davis K, et al. ODC1 is a critical determinant of MYCN oncogenesis and a therapeutic target in neuroblastoma. Cancer Res. 2008;68(23):9735–9745. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chesler L, Schlieve C, Goldenberg DD, et al. Inhibition of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase destabilizes Mycn protein and blocks malignant progression in neuroblastoma. Cancer Res. 2006;66(16):8139–8146. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chesler L, Weiss WA. Genetically engineered murine models--contribution to our understanding of the genetics, molecular pathology and therapeutic targeting of neuroblastoma. Semin Cancer Biol. 2011;21(4):245–255. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2011.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Workman P, Aboagye EO, Balkwill F, et al. Guidelines for the welfare and use of animals in cancer research. Br J Cancer. 2010;102(11):1555–1577. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blakey DC, Westwood FR, Walker M, et al. Antitumor activity of the novel vascular targeting agent ZD6126 in a panel of tumor models. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8(6):1974–1983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis PD, Dougherty GJ, Blakey DC, et al. ZD6126: a novel vascular-targeting agent that causes selective destruction of tumor vasculature. Cancer Res. 2002;62(24):7247–7253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fox E, Aplenc R, Bagatell R, et al. A phase 1 trial and pharmacokinetic study of cediranib, an orally bioavailable pan-vascular endothelial growth factor receptor inhibitor, in children and adolescents with refractory solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(35):5174–5181. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.9674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maris JM, Courtright J, Houghton PJ, et al. Initial testing of the VEGFR inhibitor AZD2171 by the pediatric preclinical testing program. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50(3):581–587. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morton CL, Maris JM, Keir ST, et al. Combination testing of cediranib (AZD2171) against childhood cancer models by the pediatric preclinical testing program. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;58(4):566–571. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walker-Samuel S, Orton M, McPhail LD, et al. Bayesian estimation of changes in transverse relaxation rates. Magn Reson Med. 2010;64(3):914–921. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boult JKR, Walker-Samuel S, Jamin Y, et al. Active site mutant dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase 1 expression confers an intermediate tumour phenotype in C6 gliomas. J Pathol. 2011;225(3):344–352. doi: 10.1002/path.2904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.D’agostino RB. Tests for normal distribution. In: D’agostino RB, Stepenes MA, editors. Goodness-of-fit techniques. Macel Decker; New York, NY: 1986. pp. 367–413. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Motulsky HJ, Brown RE. Detecting outliers when fitting data with nonlinear regression - a new method based on robust nonlinear regression and the false discovery rate. BMC bioinformatics. 2006;7(123) doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goo HW. Whole-body MRI of neuroblastoma. Eur J Radiol. 2010;75(3):306–314. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brisse HJ, McCarville MB, Granata C, et al. Guidelines for imaging and staging of neuroblastic tumors: consensus report from the International Neuroblastoma Risk Group Project. Radiology. 2011;261(1):243–257. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11101352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tozer GM, Kanthou C, Baguley BC. Disrupting tumour blood vessels. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5(6):423–435. doi: 10.1038/nrc1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morton CL, Favours EG, Mercer KS, et al. Evaluation of ABT-751 against childhood cancer models in vivo. Invest New Drugs. 2007;25(4):285–295. doi: 10.1007/s10637-007-9042-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meany HJ, Sackett DL, Maris JM, et al. Clinical outcome in children with recurrent neuroblastoma treated with ABT-751 and effect of ABT-751 on proliferation of neuroblastoma cell lines and on tubulin polymerization in vitro. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010;54(1):47–54. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robinson SP, McIntyre DJ, Checkley D, et al. Tumour dose response to the antivascular agent ZD6126 assessed by magnetic resonance imaging. Br J Cancer. 2003;88(10):1592–1597. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bradley DP, Tessier JJ, Lacey T, et al. Examining the acute effects of cediranib (RECENTIN, AZD2171) treatment in tumor models: a dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI study using gadopentate. Magn Reson Imaging. 2009;27(3):377–384. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2008.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McSheehy PM, Weidensteiner C, Cannet C, et al. Quantified tumor T1 is a generic early-response imaging biomarker for chemotherapy reflecting cell viability. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(1):212–225. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Connor JP, Carano RA, Clamp AR, et al. Quantifying antivascular effects of monoclonal antibodies to vascular endothelial growth factor: insights from imaging. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(21):6674–6682. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Batchelor TT, Sorensen AG, di Tomaso E, et al. AZD2171, a pan-VEGF receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, normalizes tumor vasculature and alleviates edema in glioblastoma patients. Cancer Cell. 2007;11(1):83–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Braunschweiger PG, Schiffer LM, Furmanski P. 1 H-NMR relaxation times and water compartmentalization in experimental tumor models. Magn Reson Imaging. 1986;4(4):335–342. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(86)91043-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robinson SP, Kalber TL, Howe FA, et al. Acute tumor response to ZD6126 assessed by intrinsic susceptibility magnetic resonance imaging. Neoplasia. 2005;7(5):466–474. doi: 10.1593/neo.04622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burrell JS, Walker-Samuel S, Baker LC, et al. Evaluation of novel combined carbogen USPIO (CUSPIO) imaging biomarkers in assessing the antiangiogenic effects of cediranib (AZD2171) in rat C6 gliomas. Int J Cancer. 2012 doi: 10.1002/ijc.27460. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nathan P, Zweifel M, Padhani AR, et al. Phase I Trial of Combretastatin A4 Phosphate (CA4P) in Combination with Bevacizumab in Patients with Advanced Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(12):3428–3439. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-3376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Waterton JC, Pylkkanen L. Qualification of imaging biomarkers for oncology drug development. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48(4):409–415. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bradley DP, Tessier JJ, Ashton SE, et al. Correlation of MRI biomarkers with tumor necrosis in Hras5 tumor xenograft in athymic rats. Neoplasia. 2007;9(5):382–391. doi: 10.1593/neo.07145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jackson A, O’Connor JP, Parker GJ, Jayson GC. Imaging tumor vascular heterogeneity and angiogenesis using dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(12):3449–3459. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McPhail LD, McIntyre DJ, Ludwig C, et al. Rat tumor response to the vascular-disrupting agent 5,6-dimethylxanthenone-4-acetic acid as measured by dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging, plasma 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid levels, and tumor necrosis. Neoplasia. 2006;8(3):199–206. doi: 10.1593/neo.05739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sinkus R, Van Beers BE, Vilgrain V, DeSouza N, Waterton JC. Apparent diffusion coefficient from magnetic resonance imaging as a biomarker in oncology drug development. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48(4):425–431. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Humphries PD, Sebire NJ, Siegel MJ, Olsen OE. Tumors in pediatric patients at diffusion-weighted MR imaging: apparent diffusion coefficient and tumor cellularity. Radiology. 2007;245(3):848–854. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2452061535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.