Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to examine practice variability and compare outcomes between early and delayed neonatal inguinal hernia repair (IHR)

Methods

Patients admitted to neonatal intensive care units with a diagnosis of IH who underwent IHR by age 1 year in the Pediatric Health Information System from 1999-2011 were included. IHR after the index hospitalization was considered delayed. Inter-hospital variability in the proportion of delayed repairs and differences in outcomes for each group were compared. A propensity score matched analysis was performed to account for baseline differences between treatment groups.

Results

Of the 2,030 patients identified, 32.9% underwent delayed IHR with significant variability in the proportion of patients having delayed repair across hospitals (p<0.0001). More patients in the delayed group had a congenital anomaly or received life supportive measures prior to IHR (all p<0.01), and 8.2% of patients undergoing delayed repair had a diagnosis of incarceration at repair. More patients in the early group underwent reoperation for hernia within 1 year (5.9% vs. 3.7%, p=0.02). Results were similar after performing a propensity score matched analysis.

Conclusions

Significant variability in practice exists between children's hospitals in the timing of IHR, with delayed repair associated with incarceration and early repair with a higher rate of reoperation.

Keywords: Inguinal hernia, neonate, PHIS, delayed repair, inguinal hernia repair

Introduction

The optimal timing for repair of neonatal inguinal hernias remains controversial. A study of pediatric surgeon practices in 2005 revealed that only 63% of surgeons reported they repair inguinal hernias diagnosed in hospitalized premature infants prior to discharge.[1] Among other things, timing of inguinal hernia repair (IHR) must balance the perioperative risks associated with earlier repair with the potential for hernia incarceration if repair is delayed. Rates of hernia incarceration in patients referred for delayed repair have been reported to be between 0-41%, while the need for post-operative respiratory support following early repair has been documented to be as high as 38%.[2-8] Definitive studies comparing outcomes of early and delayed repair have yet to been performed. Current guidelines from the Committee on Fetus and Newborn and the Section on Surgery of the American Academy of Pediatrics conclude that early repair should be balanced against the risk of postoperative complications in this vulnerable population.[9]

The purpose of this study was to develop a multi-institutional cohort of patients in the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) database in order to (1) assess practice variability in the timing of IHR; (2) identify the rate of incarceration in patients with delayed IHR; (3) and compare outcomes of early versus delayed repair in matched cohorts of neonates with similar observed baseline characteristics.

Methods

Data Source and Cohort Development

The Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) is an administrative database with data from 44 free-standing children's hospitals that includes demographic information and International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision – Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis codes, and date-stamped codes for procedures, radiologic and laboratory tests, medications, and supplies. Data from the 25 hospitals that contributed inpatient, emergency department (ED), ambulatory surgery, and observation encounters during the study period were included.

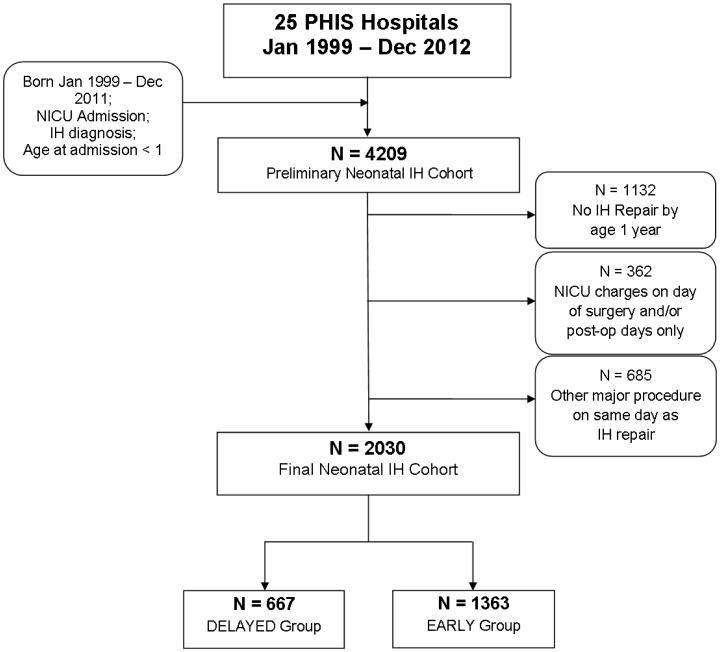

Patients born between January 1999 and December 2011 who had a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission prior to 1 year of age associated with the diagnosis code for an inguinal hernia (ICD-9-CM 550.x) were included in the initial cohort (Figure 1). In order to create a cohort of patients who were treated for a diagnosed hernia, did not have an IHR performed due to the convenience of performing this procedure within the same anesthetic as another procedure, and who were not in the ICU as the result of a transfer from another hospital's ICU for pre-operative evaluation prior to early repair, we applied the following exclusion criteria: (1) An IHR code was not documented by 1 year of age; (2) An additional elective operative procedure code was documented on the same day as IHR; (3) charges for time spent in the ICU were only present on the day of IHR and/or in the days after IHR. The treatment group classification as early versus delayed was determined by whether the IHR was performed during the first encounter at which the IH diagnosis code was present (early group) or at a subsequent encounter (delayed group). Chart review validation was performed at four of the 25 PHIS hospitals to estimate the misclassification rates within the PHIS (Nationwide Children's Hospital, Columbus, OH; Children's Hospital of Atlanta, Atlanta, GA; Children's Hospital Boston, Boston, MA; Monroe Carell Jr Children's Hospital, Nashville, TN). The validation cohort represented 21.8% of the total cohort. This study was approved by the institutional review board of each institution.

Figure 1.

PHIS search strategy and treatment group allocation.

Exposures and Outcomes

Demographic and clinical characteristics from the initial admission with an inguinal hernia diagnosis were included. For the purposes of standardization, we focused on patient characteristics present before the time of the treatment decision which was defined as the date of IHR in the early group and the date of hospital discharge in the delayed group. The average annual volume of inguinal hernia cases at each hospital was also evaluated.

Outcomes were evaluated up to one year following IHR. The primary outcomes for comparison between the early and delayed groups were the rates of readmission and hernia reoperation at 30 days and one year. Hernia reoperation was defined as the presence of an additional procedure code subsequent to the first and was independent of diagnosis codes for recurrence; as such these events could represent hernia recurrences or metachronous contralateral hernias; the underlying premise being that needing an additional hernia surgery whether it be for recurrence or an unaddressed contralateral hernia represents an adverse outcome. The rate of pre-operative incarceration in the delayed group is reported as the percentage of patients who had a diagnosis of an incarcerated, strangulated, or gangrenous inguinal hernia (ICD-9-CM 550.0, 550.1) at the encounter at which the IHR occurred.

Statistical Analysis

Exposures were reported for the entire cohort using medians and interquartile ranges for continuous variables and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. Group comparisons were made using two sample t-tests or Wilcoxon rank sum tests for continuous variables and Pearson chi square or Fisher's exact tests for categorical variables. Logistic and linear mixed effects models were fit to assess the associations between treatment type and binary and continuous outcomes, respectively. Inter-hospital variability in the proportion of patients treated with delayed IHR was examined before and after adjustment using logistic mixed effects models with random hospital intercepts, with adjustment for variables with significant differences between treatment groups in bivariate analyses.

Since this study utilizes a retrospective database and compares two groups of patients with different baseline characteristics, we performed a propensity score matched analysis to closely match patients in each group on important demographic and baseline clinical characteristics; this allows for comparison of patients from each treatment group with balanced baseline characteristics. In the estimation of propensity scores, the following characteristics that may potentially affect treatment choice and could be determined from PHIS were considered: hospital at which the patient was treated, age at index admission, gender, birth weight, gestational age at birth, race, payer status, prematurity, slow fetal growth or fetal malnutrition, congenital anomalies (all body systems were considered individually), necrotizing enterocolitis, exposure to mechanical ventilation, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, total parenteral nutrition, and blood products, length of stay prior to the treatment decision, incarceration diagnosis, and hospital caseload of neonatal inguinal hernia patients. Propensity score matching was done using the gmatch SAS macro.[10] To include variables with missing data, multiple imputation was used to create 20 complete data sets and propensity scores were estimated for each data set, then averaged.[11] All baseline characteristics (Table 1) associated with treatment group at p≤0.20 in bivariate analyses were used to estimate propensity scores, and statistically significant interactions were included (See Results Section: Propensity Score Matched Group Comparisons). Early and delayed group patients were matched on the logit of their average propensity score using 1:1 nearest neighbor matching within calipers of width equal to 0.25 times the standard deviation of the logit of the propensity score.[12, 13] To assess the balance between early and delayed groups after propensity score matching in all available exposures present before the treatment decision was made, standardized differences were computed and it was confirmed that all were ≤0.10. The analyses performed in the original cohort were then performed on the propensity score matched cohort. Several sensitivity analyses were performed to assess any potential biases caused by: 1) excluding the patients who only had charges for time spent in the ICU on the day of IHR and/or in the days after IHR repair from the early cohort; and 2) misclassification of hernia reoperation and hernia-related readmission in PHIS.[14] Analyses were performed using SAS v9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Table 1. Characteristics of Patient Population during initial admission with Inguinal Hernia Diagnosis.

| Total Cohort (N=2030) | Propensity-score matched cohort (N=944) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Early (N=1363) | Delayed (N=667) | P | Early (N=472) | Delayed (N=472) | P |

| Age at admission (days) | 8 (0, 67) | 3 (0, 52) | 0.002 | 7 (0, 66) | 11 (0, 62) | 0.90 |

| Age at hernia repair (days) | 84 (57, 108) | 153 (112, 207) | <.001 | 88 (58, 110) | 153 (111, 212) | <.001 |

| Male | 1157 (84.9) | 603 (90.4) | <.001 | 422 (89.4) | 423 (89.6) | 0.92 |

| Birth Weight (g)a | 920 (720,1392) | 910 (709, 1343) | 0.29 | 977 (731,1500) | 1016 (750, 1468) | 0.53 |

| Post conceptual age at hernia repair (weeks)b | 39 (37, 42) | 49 (44, 55) | <.001 | 40 (38, 43) | 49 (44, 56) | <.001 |

| Gestational age (weeks)b | 27 (25, 30) | 28 (25, 31) | 0.07 | 28 (25, 31) | 28 (26, 31) | 0.49 |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 768 (56.4) | 359 (53.8) | 0.20 | 255 (54.0) | 256 (54.2) | 0.99 |

| Black | 340 (24.9) | 191 (28.6) | 90 (19.1) | 91 (19.3) | ||

| Other/Unknown | 255 (18.7) | 117 (17.5) | 127 (26.9) | 125 (26.5) | ||

| Insurance | ||||||

| Government | 732 (53.7) | 348 (52.2) | 0.006 | 261 (55.3) | 257 (54.4) | 0.94 |

| Private | 497 (36.5) | 222 (33.3) | 148 (31.4) | 153 (32.4) | ||

| Other/Unknown | 134 (9.8) | 97 (14.5) | 63 (13.3) | 62 (13.1) | ||

| Premature | 938 (68.8) | 483 (72.4) | 0.10 | 314 (66.5) | 317 (67.2) | 0.84 |

| Any congenital anomaly | 848 (62.2) | 452 (67.8) | 0.01 | 308 (65.3) | 301 (63.8) | 0.63 |

| Respiratory failure | 586 (43.0) | 312 (46.8) | 0.11 | 193 (40.9) | 186 (39.4) | 0.64 |

| NEC | 108 (7.9) | 47 (7.1) | 0.48 | 35 (7.4) | 28 (5.9) | 0.36 |

| Mechanical ventilationc | 1044 (76.6) | 568 (85.2) | <.001 | 385 (81.6) | 389 (82.4) | 0.73 |

| TPNc | 845 (62.0) | 499 (74.8) | <.001 | 328 (69.5) | 323 (68.4) | 0.73 |

| Blood product c | 478 (35.1) | 312 (46.8) | <.001 | 203 (43.0) | 198 (41.9) | 0.74 |

| LOS (days) prior to hernia repair (early) or discharge (delayed) | 48 (3, 85) | 54 (18, 87) | <.001 | 48 (8, 89) | 46 (11, 83) | 0.86 |

| Total LOS (days) initial admission | 59 (9, 99) | 54 (18, 87) | 0.38 | 64 (17, 106) | 46 (11, 83) | <.001 |

| Incarceration diagnosis at initial admission | 161 (11.8) | 10 (1.5) | <.001 | 11 (2.3) | 10 (2.1) | 0.83 |

| Hospital's average annual case load of neonatal inguinal hernia patients | ||||||

| 1-6 | 220 (16.1) | 133 (19.9) | <.001 | 109 (23.1) | 102 (21.6) | 0.72 |

| 6-10 | 374 (27.4) | 239 (35.8) | 159 (33.7) | 154 (32.6) | ||

| >10 | 769 (56.4) | 295 (44.2) | 204 (43.2) | 216 (45.8) | ||

Data are presented as number of patients (%) or median (IQR).

Early cohort N=896, Delayed Cohort N=487.

Early cohort N=819, Delayed Cohort N=419.

For the early group, only days prior to the hernia repair were included. NEC, necrotizing enterocolitis; TPN, total parenteral nutrition; LOS, length of stay.

Results

Inguinal Hernia Cohort and Institutional Practice Variability

During the study period, there were 2,030 neonates identified with an inguinal hernia, with 1,363 patients (67.1%) undergoing early IHR and 667 patients (32.9%) undergoing delayed IHR. Chart validation was performed for 443 patients treated at 4 PHIS hospitals (21.8% of the total cohort) demonstrated misclassification rates of 0% for the diagnosis of inguinal hernia, 5.4% for the treatment group assignment, 0% for mortality, 3.2% for reoperation, 7.2% for incarceration and 8.3% for hernia-related readmission.

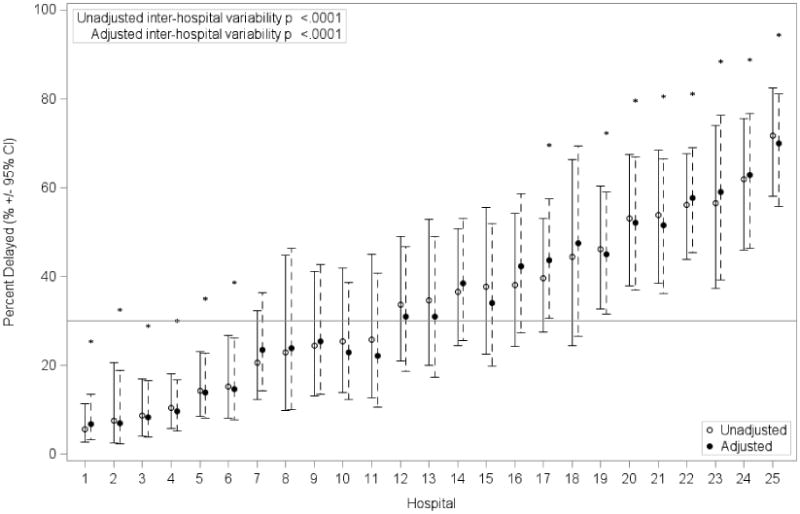

Significant variability exists across the 25 hospitals in the proportion of patients undergoing delayed IHR in both the unadjusted models and adjusted models (Figure 2). The hospital-specific proportions of delayed IHR before adjustment ranged from 3% to 74%. When stratified by time period (1999-2003, 2004-2007, 2008-2012), there were no significant changes over time in hospital-specific proportions of delayed IHR.

Figure 2.

Variability between PHIS hospitals in the timing of inguinal hernia repair in neonates.

Unadjusted (open circles and solid lines) and adjusted (closed circles and dotted lines) estimates of the percentage of patients with delayed inguinal hernia repair at each hospital with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Adjustments included: age at the index admission; gender; insurance source; prematurity; the presence of any congenital anomaly plus other specific anomalies (hepatobiliary, renal, musculoskeletal, genetic, and respiratory); mechanical ventilation, total parenteral nutrition prior to the treatment decision, blood product transfusion prior to the treatment decision; and the length of stay prior to the treatment decision. * = Hospitals that wre significant outliers compared to the overall mean (as shown by the reference line).

Baseline characteristics of the groups are shown in Table 1. Compared to the early group, the delayed group had more males, more congenital anomalies, more often received mechanical ventilation, total parenteral nutrition (TPN), or blood products, and had a longer LOS prior to the IHR treatment decision.

Incarceration and Outcomes

In the early group, 161 patients (11.8%) had a diagnosis of incarceration during their initial admission compared with 10 patients (1.5%) in the delayed group (Table 1). Subsequent to their initial admission, 55 patients (8.2%) in the delayed group presented to the hospital with a diagnosis of incarceration at the encounter in which IHR was performed, (Table 2). Differences in post-operative outcomes between treatment groups are shown in Table 2. Within 30 days of surgery, there was no difference between groups in the proportion of patients with ED visits. Patients in the early group were more often readmitted, more likely to receive post-operative mechanical ventilation, TPN, and blood products, and had a longer post-operative length of stay (Table 2). Within 1 year after surgery, the rate of reoperation for IH was higher in the early group (5.9% vs. 3.7%, p=0.02) (Table 2). In hospital mortality (0.7% Early vs. 0.1% Delayed, p=0.18) and the rate of hernia-related readmissions (3.4% vs. 3.1%, p=0.72) at 1 year were similar between groups (Table 2).

Table 2. Incarceration and Post-Operative Hernia Outcomes.

| Total Cohort | Propensity Score Matched Cohort | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Early (N=1363) | Delayed (N=667) | P | Early (N=472) | Delayed (N=472) | P | ||||

| Incarceration diagnosis while awaiting repair in delayed group | NA | 8.2 | (55) | NA | 9.5 | (45) | ||||

| Post-operative outcomes at same encounter as IH repair | ||||||||||

| Post-op length of stay (days) | 6 | (2, 14) | 1 | (0, 1) | <.001 | 6 | (3, 15) | 1 | (0, 1) | <.001 |

| Mechanical ventilation post-op | 707 | (51.9) | 98 | (14.7) | <.001 | 239 | (50.6) | 72 | (15.3) | <.001 |

| TPN post-op | 167 | (12.3) | 15 | (2.2) | <.001 | 70 | (14.8) | 13 | (2.8) | <.001 |

| Blood product post-op | 32 | (2.3) | 5 | (0.7) | 0.02 | 13 | (2.8) | 3 | (0.6) | 0.02 |

| Post-operative outcomes within 30 days of discharge from encounter with IH repair | ||||||||||

| Any readmission* | 177 | (13.0) | 63 | (9.4) | 0.02 | 71 | (15.0) | 48 | (10.2) | 0.03 |

| Readmission associated with SSI, wound complication, UTI, or Pneumonia* | 38 | (2.8) | 18 | (2.7) | 0.96 | 16 | (3.4) | 12 | (2.5) | 0.46 |

| Hernia-related readmissions | 11 | (0.8) | 7 | (1.1) | 0.59 | 4 | (0.9) | 5 | (1.1) | 0.76 |

| Any ED visit | 115 | (8.4) | 61 | (9.1) | 0.78 | 47 | (10.0) | 45 | (9.5) | 0.85 |

| ED visit with SSI, wound complication, UTI, or Pneumonia | 6 | (0.4) | 4 | (0.6) | 0.74 | 3 | (0.6) | 3 | (0.6) | 1.0 |

| Reoperation for Hernia | 10 | (0.7) | 6 | (0.9) | 0.67 | 4 | (0.8) | 4 | (0.8) | 1.0 |

| Post-operative outcomes within 1 year of discharge from encounter with IH repair | ||||||||||

| Any readmission* | 502 | (36.8) | 225 | (33.7) | 0.19 | 191 | (40.5) | 171 | (36.2) | 0.17 |

| Readmission associated with SSI, wound complication, UTI, or Pneumonia* | 151 | (11.1) | 71 | (10.6) | 0.76 | 52 | (11.0) | 51 | (10.8) | 0.92 |

| Hernia-related readmissions | 47 | (3.4) | 21 | (3.1) | 0.72 | 22 | (4.7) | 16 | (3.4) | 0.34 |

| Any ED visit | 459 | (33.7) | 266 | (39.9) | 0.046 | 166 | (35.2) | 193 | (40.9) | 0.07 |

| ED visit with SSI, wound complication, UTI, or Pneumonia | 36 | (2.6) | 24 | (3.6) | 0.40 | 15 | (3.2) | 20 | (4.2) | 0.39 |

| Reoperation for Hernia | 81 | (5.9) | 25 | (3.7) | 0.02 | 38 | (8.1) | 15 | (3.2) | 0.002 |

| In-hospital mortality | 9 | (0.7) | 1 | (0.1) | 0.18 | 5 | (1.1) | 0 | (0) | 0.06 |

Data are presented as number of patients (%) or median (IQR).

Readmissions included inpatient and observation encounters. Unless otherwise specified, encounters included ED, inpatient, observation, and ambulatory surgery encounters. P values are from linear or logistic mixed effects models with a random hospital effect or from Fisher exact tests in the case of rare outcomes. IH, inguinal hernia; TPN, total parenteral nutrition; SSI, surgical site infection; UTI, urinary tract infection; ED, emergency department.

Propensity Score Matched Group Comparisons

Propensity score modeling included those baseline characteristics shown in Table 1 that differed between treatment groups in the total cohort at p≤.20, and several unlisted characteristics that also met this p-value threshold, namely the presence of a hepatobiliary anomaly, renal anomaly, musculoskeletal anomaly, or genetic anomaly. Several significant first order interactions were also included. Characteristics that most significantly predicted delayed repair in the model used to estimate the propensity scores were the following: the hospital in which the patient was treated, not having a diagnosis of incarceration at the index admission, mechanical ventilation prior to the time of the treatment decision, and prematurity (the effect of which was more pronounced at hospitals with higher rates of delayed repair). Propensity score matching produced two groups of 472 patients each with all baseline characteristics prior to the time of the treatment decision similar between the two groups, though the delayed group had a shorter total LOS during their initial admission (Table 1).

After matching, 11 (2.3%) of the 472 patients in the early group had a diagnosis of incarceration during their initial admission compared to 10 patients (2.1%) in the delayed group (Table 1). Subsequent to their initial admission, 45 patients (9.5%) in the delayed group presented to the hospital with a diagnosis of incarceration at the encounter in which IHR was performed, (Table 2). Differences in post-operative outcomes between propensity score matched groups are shown in Table 2. Similar to the overall cohort, there was no difference between groups in the proportion of patients with ED visits; patients in the early group were more often readmitted, more likely to receive post-operative mechanical ventilation, TPN, and blood products, and had a longer post-operative length of stay (Table 2). One year following surgery, patients in the early group more frequently required reoperation for IH (8.1% vs. 3.2%, p=0.002) (Table 2). In-hospital mortality (1.1% early vs. 0% delayed, p=0.06) and hernia-related readmission rates (4.7% vs. 3.4%, p=0.34) at 1 year were similar between groups (Table 2).

Sensitivity Analyses

Analyses that included 277 patients who had ICU charges only on the day of IHR and/or in the days after IHR repair in the early group and who did not have other major surgical procedures on the day of IHR, demonstrated similar results in terms of differences between the early (N=1640) and delayed (N=667) groups in patient characteristics and outcomes (data not shown). However, compared to the originally included early patients, the newly included patients were significantly older at the time of their admission for hernia repair, had higher birth weights, were less likely to carry diagnoses of prematurity, any congenital anomaly, respiratory failure, or NEC at the PHIS hospital, were more likely to have incarcerated hernia, and were less likely to have used TPN, mechanical ventilation, or blood products preoperatively at the PHIS hospital (p<.05 for all). Analyses examining the effects of misclassification of treatment group, hernia reoperation, and readmission, at the rates detected in our chart review validation study, demonstrated that the 30 day and 1 year rates of each of these outcomes would be somewhat higher than the rates found in PHIS if misclassification were nonexistent. However, comparisons of these rates between early and delayed treatment groups would yield similar findings, with the exception of reoperation rates at one year, which demonstrated similar differences between the groups but would no longer differ significantly in the overall cohort (p=0.16) or the propensity matched cohort (p=0.08).

Discussion

In this multi-institutional cohort of neonates, there was significant practice variability in the timing of IHR across PHIS hospitals. After propensity score matching, patients undergoing delayed repair had a higher rate of incarceration prior to undergoing IHR compared to the early group (9.5% vs. 2.3%); however, patients undergoing delayed IHR had a lower rate of hernia reoperation within in 1 year compared to the early group (3.2% vs. 8.1%).

There is ongoing debate about the optimal timing of IHR in hospitalized neonates. The most recent survey from the AAP found that more than half of surgeons would repair a hernia in a former premature infant identified after discharge “when convenient” while just under two-thirds would repair a hernia discovered in an inpatient prior to discharge.[1] In this study, the proportion of patients undergoing delayed IHR ranged from 3% to 74% across the 25 hospitals. Even after adjusting for differences in the patients treated at each hospital, substantial variability remained. This data suggests that the treating hospital is an important factor in determining timing of IHR. This variability underscores the need for better evidence to guide practitioners in selecting patients for either treatment strategy.

Advocates of early IHR cite the potential risks associated with hernia incarceration if repair is delayed.[15, 16] Delaying IHR has been shown to increase the odds that an infant's hernia will incarcerate with several studies demonstrating that the risk of incarceration doubles after a prolonged delay.[4, 7] However, other studies have reported lower rates of hernia incarceration after delayed repair, including one study that had no cases of incarcerated hernia in 35 neonates discharged from the NICU with a diagnosed hernia.[8] In the current study, hernia incarceration was identified in less than 10% of the patients who underwent a delayed repair. Taken together, these data suggest that delayed IHR may be a reasonable option for selected patients with families that can understand the potential risk and benefits. Because of the risk of hernia incarceration, it is particularly important to consider the comfort level of the patient's guardians and their proximity to appropriate surgical care when selecting patients for delayed repair.[17]

In contrast, performing an early hernia repair in a neonate is associated with its own set of risks, including increased technical difficulty and respiratory complications such as post-operative apnea and prolonged mechanical ventilation.[6, 8, 9, 18-20] However, interpretation of outcomes from these studies is confounded by selection bias. The results of this PHIS cohort study highlight this selection bias with patients in the delayed group having higher rates of critical care interventions, suggesting a greater initial severity of illness. For this reason we conducted a propensity score matched analysis to compare patients from each group with similar measurable characteristics. After matching, patients in the early group had a longer post-operative LOS, required more critical care interventions, and had higher rates of readmissions within 30 days and hernia reoperation at 1 year. Although many of these outcomes may be heavily influenced by baseline characteristics not fully accounted for by propensity score matching, these findings suggest that early IHR may also be associated with significant morbidity.

An additional concern for early IHR is the potential neurodegenerative effects of various sedatives and anesthetics in neonates.[21-23] Small animal studies have demonstrated significant neuronal injury and neurocognitive deficits following administration of the major categories of anesthetics and sedatives, while non-human primate studies have shown neurodegeneration after administering isoflurane and ketamine for relatively long durations.[24-27] Although human studies are limited to retrospective series, the available data suggests an association between neonatal and young childhood exposure to general anesthesia and a higher likelihood for behavioral disorders or learning disabilities later in childhood.[21-23] With respect to the present study, the age differential between the early and delayed groups was only on the order of several months, which may not be a long enough delay to avoid these potential neurodegenerative effects of anesthesia. However, as we learn more about these risks, it is possible that even such a short period of delay may be important for neurogenesis and this may become an important factor in determining the timing of non-urgent neonatal surgery.

Limitations of this study are consistent with similar studies using multi-institutional administrative databases. First, misclassification of data can occur secondary to errors in coding and data entry. We performed a multi-institutional validation of the PHIS data on 21.8% of the total cohort to confirm low misclassification rates of important exposures and outcomes in this study. Second, although the PHIS database allows for longitudinal follow up of patients across multiple encounters, any encounters that took place at other institutions would not be included. Finally, administrative data is limited in its ability to describe certain clinical outcomes. For example, diagnosis codes are associated with an entire encounter and do not have date stamps like procedures, so it is difficult to determine the temporal relationship of certain outcomes.

In conclusion, significant variability exists across PHIS hospitals in the proportion of patients undergoing delayed IHR. In this study, after propensity score matching, delayed IHR was associated with a 9.5% incarceration rate. In contrast, patients treated with early IHR had higher rates of hernia reoperation within 1 year. These results suggest that delayed IHR may be a reasonable option in selected patients, however further investigation is warranted. An ongoing multi-institutional randomized controlled trial comparing early to delayed neonatal inguinal hernia repair may help to identify differences in outcomes.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Antonoff MB, Kreykes NS, Saltzman DA, et al. American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Surgery hernia survey revisited. Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 2005;40:1009–1014. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Uemura S, Woodward AA, Amerena R, et al. Early repair of inguinal hernia in premature babies. Pediatric Surgery International. 1999;15:36–39. doi: 10.1007/s003830050507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Misra D. Inguinal hernias in premature babies: wait or operate? Acta Paediatrica. 2001;90:370–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zamakhshary M, To T, Guan J, et al. Risk of incarceration of inguinal hernia among infants and young children awaiting elective surgery. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2008;179:1001–1005. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.070923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen LE, Zamakhshary M, Foglia RP, et al. Impact of wait time on outcome for inguinal hernia repair in infants. Pediatric Surgery International. 2009;25:223–227. doi: 10.1007/s00383-008-2306-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vaos G, Gardikis S, Kambouri K, et al. Optimal timing for repair of an inguinal hernia in premature infants. Pediatric Surgery International. 2010;26:379–385. doi: 10.1007/s00383-010-2573-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lautz TB, Raval MV, Reynolds M. Does timing matter? A national perspective on the risk of incarceration in premature neonates with inguinal hernia. Journal of Pediatrics. 2011;158:573–577. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.09.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee SL, Gleason JM, Sydorak RM. A critical review of premature infants with inguinal hernias: optimal timing of repair, incarceration risk, and postoperative apnea. Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 2011;46:217–220. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2010.09.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang KS Committee on the Fetus and Newborn of the American Academy of Pediatrics. Assessment and management of inguinal hernia in infants. Pediatrics. 2012;130:768–773. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kosanke J, Bergstralh E GMATCH. Mayo Clinic Division of Biomedical Statistics and Informatics. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schafer JL. Multiple imputation: a primer. Statistical Methods in Medical Research. 1999;8:3–15. doi: 10.1177/096228029900800102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Faries DE, Leon AC, Haro JM, et al. Analysis of observational health care data using SAS. Cary, N C.: SAS Institute; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitra R, Reiter JP. A comparison of two methods of estimating propensity scores after multiple imputation. Statistical Methods in Medical Research. 2012 doi: 10.1177/0962280212445945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lash TL, Fink AK. Semi-automated sensitivity analysis to assess systematic errors in observational data. Epidemiology. 2003;14:451–8. doi: 10.1097/01.EDE.0000071419.41011.cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nagraj S, Sinha S, Grant H, et al. The incidence of complications following primary inguinal herniotomy in babies weighing 5 kg or less. Pediatric Surgery International. 2006;22:500–502. doi: 10.1007/s00383-006-1695-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Erdogan D, Karaman I, Aslan MK, et al. Analysis of 3,776 pediatric inguinal hernia and hydrocele cases in a tertiary center. Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 2013;48:1767–1772. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2012.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller GG. Waiting for an operation: parents' perspectives. Canadian Journal of Surgery. 2004;47:179–181. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Phelps S, Agrawal M. Morbidity after neonatal inguinal herniotomy. Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 1997;32:445–447. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(97)90602-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murphy JJ, Swanson T, Ansermino M, et al. The frequency of apneas in premature infants after inguinal hernia repair: do they need overnight monitoring in the intensive care unit? Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 2008;43:865–868. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2007.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baird R, Gholoum S, Laberge JM, et al. Prematurity, not age at operation or incarceration, impacts complication rates of inguinal hernia repair. Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 2011;46:908–911. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2011.02.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DiMaggio C, Sun LS, Kakavouli A, et al. A retrospective cohort study of the association of anesthesia and hernia repair surgery with behavioral and developmental disorders in young children. Journal of Neurosurgical Anesthesiology. 2009;21:286–291. doi: 10.1097/ANA.0b013e3181a71f11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilder RT, Flick RP, Sprung J, et al. Early exposure to anesthesia and learning disabilities in a population-based birth cohort. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:796–804. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000344728.34332.5d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bong CL, Allen JC, Kim JT. The effects of exposure to general anesthesia in infancy on academic performance at age 12. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2013;117:1419–1428. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e318299a7c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fredriksson A, Ponten E, Gordh T, et al. Neonatal exposure to a combination of N-methyl-D-aspartate and gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor anesthetic agents potentiates apoptotic neurodegeneration and persistent behavioral deficits. Anesthesiology. 2007;107:427–436. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000278892.62305.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stratmann G, Sall JW, May LD, et al. Isoflurane differentially affects neurogenesis and long-term neurocognitive function in 60-day-old and 7-day-old rats. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:834–848. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31819c463d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brambrink AM, Evers AS, Avidan MS, et al. Isoflurane-induced neuroapoptosis in the neonatal rhesus macaque brain. Anesthesiology. 2010;112:834–841. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181d049cd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zou X, Patterson TA, Divine RL, et al. Prolonged exposure to ketamine increases neurodegeneration in the developing monkey brain. International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience. 2009;27:727–731. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]