Abstract

Introduction: Murdannia loriformis (hassk) Rolla Roa et Kammathy, family Commelinaceae, is used by Chinese practitioners as a remedy for cancer in an early stage, and also for treating other diseases including colds, throat infections, pneumonia, diabetes mellitus, flu and inflammation. Although anticancer as well as other pharmacological effects of M. loriformis have been reported, its anti-inflammatory and other activities related to inflammation are still limited.

Methods: The anti-inflammatory activity was evaluated using carrageenan- and arachidonic acid-induced paw edema in rats, and cotton pellet-induced granuloma formation in rats. The analgesic and antipyretic activities were determined by formalin test in mice and yeast-induced hyperthermia in rats, respectively.

Results: The ethanol extract of the aerial part of M. loriformis exhibited anti-inflammatory activity on the rat paw edema induced by carrageenan and arachidonic acid. It also showed an inhibitory effect on the granuloma and the transudative formation of the rat implanted with cotton pellets as well as lowered the elevated serum alkaline phosphatase activity to normal level. It exerted potent analgesic effect on both the early and late phase of formalin test as well as the antipyretic effect on yeast-induced hyperthermic rats. The oral single high dose of the extract of 5,000 mg/Kg did not produce death or any abnormalities or changes of the internal organs of rats during 14 days of the observed period.

Conclusion: The results obtained from this study support the use of the plant in traditional medicine for inflammatory ailments.

Keywords: Anti-inflammatory activity, Analgesic and antipyretic activities, Acute toxicity, Murdannia loriformis, In vivo study

Introduction

Murdannia loriformis (hassk) Rolla Roa et Kammathy, family Commelinaceae, is used by Chinese practitioners as a remedy for cancer in an early stage, and for treating other diseases including colds, throat infections, pneumonia, diabetes mellitus, flu and inflammation such as inflamed wound.1 In 1984, M. loriformis has become famous in Thailand when some cancer patients recovered after drinking its fresh juice.2 It is claimed to have a potential for treating, healing or protecting against cancer by strengthening the immune system. Many studies revealed its effectiveness as an anticancer, antioxidant and anticarcinogen.2 Phytochemical study showed that M. loriformis contains phytosterylglycoside and glycosphingolipid, which elicited immunomodulatory properties and a moderate cytotoxicity with an ED50 of 16 µg/ml against human breast ATCC HTB20 (BT474) and colon (SW620) cancer cell lines.3 Glycoside and aglycone of the plant have been reported to be cytotoxic against breast cancer and colon cancer cell lines.2 Although anticancer as well as other pharmacological effects of M. loriformis have been reported, its anti-inflammatory and other activities related to inflammation are still limited. Moreover, there is an evidence of a close relationship between cancer and inflammation. From the previous studies, COX-2-derived prostaglandins may have an important role in tumor viability and growth, as well as control of metastasis.4-6 Therefore, this plant may be potential as an anti-inflammatory agent as well. Preliminary screening of the M. loriformis extract for anti-inflammatory activity revealed marked inhibition on ear edema induced by ethyl phenylpropiolate (EPP).

In the present study, we evaluated the anti-inflammatory, analgesic and antipyretic activities in various animal models in comparison with reference drugs. The mechanisms of the anti-inflammatory action as well as acute oral toxicity were also investigated.

Materials and methods

Plant material and extract

M. loriformis was collected from Petchaburi province, Thailand. The voucher specimen (QBG.No.25135) was deposited in the herbarium section of Queen Sirikit Botanical Garden, Chiang Mai, Thailand. Dry powder of the aerial part (700 g) was extracted with 80% ethanol (4 × 4L) using a stirrer at room temperature. The extract was filtered and the combined filtrate was evaporated to dryness under reduced pressure at 55 °C and lyophilized to give the crude extract of M. loriformis, designated as ML extract, (96.7 g or 13.8% yield).

Experimental animals

Male and female Sprague-Dawley rats weighing 100-110 g and 200-210 g as well as male Swiss albino mice weighing 35-40 g were purchased from the National Laboratory Animal Center, Nakorn Pathom. All animals were kept in a room maintain under environmentally controlled conditions of 24 ± 1 °C and 12 h light-12 h dark cycle. All animals had free access to water and standard diet. They were acclimatized for at least one week before starting the experiments.

Preparation of test drugs and drug administration

All test drugs were suspended in 5% polysorbate 80 U.S.P. and orally administered in an equivalent volume of 0.5 ml/100 g body weight of the rats and 0.1 ml/10 g body weight of the mice.

Anti-inflammatory studies

Carrageenan- and arachidonic acid-induced hind paw edema in rats

Carrageenan- or arachidonic acid (AA)- induced high paw edema models were performed following the methods described previously.7,8 Male rats weighing between 100-120 g were used and divided into groups of six animals. The rats were pre-treated with vehicle, test drugs, or ML extract 1 and 2 h prior to carrageenan and AA injection, respectively. Carrageenan (1% in normal saline solution 0.05 ml) or AA (0.5% in 0.2 M carbonate buffer, 0.1 ml) was injected intradermally into the plantar side of the right high paw of the rats. The paw volume was measured by using a plethysmometer (model 7150 Ugo Basile, Italy) before and at 1, 3, and 5 h after carrageenan or 1 h after AA injection. Data obtained from control groups (received vehicle) were used for comparison with those obtained from test drugs.

Cotton pellet-induced granuloma formation and transudation in rats

Male rats weighing between 200-210 g were divided into four groups of six animals. The rats were anesthetized with ether. Two pellets of cotton wool (20 ± 1 mg) were implanted subcutaneously, one on each side of the abdomen of the rat under light anesthesia and sterile technique according to the method described by Swingle and Shideman.9 Test drugs were orally administered once per day for 7 days. At the end of experiment (day eighth), rats were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg, intraperitoneally). The cotton pellets were dissected out, weighed for wet weight, dried at 60 °C for 18 h, and weighed after cooling. The body weight gain and the dry weight of the thymus gland were measured.

Alkaline phosphatase activity in serum of cotton pellet implanted rats

The rat from the cotton pellet-induced granuloma formation model was further available for detection of other parameters. The blood was collected from common carotid artery and then transferred into a tube. Alkaline phosphatase and total proteins were measured.10

Evaluation of the ulcerogenic effect

After blood collection, the abdomen of each animal from the cotton pellet-induced granuloma formation model was opened. The stomach was removed and opened. The lesions were examined from the glandular portion of the stomach. Measurement of the lesions was performed according to the methods described by Milano and colleagues.11 The length of gastric lesion (mm) was measured under microscope. The grade of lesion was scored. Sum of the total scores of rats in each group was shown as the median ulcer index.

Analgesic test (formalin test)

Male Swiss-albino mice (35-40 g) were divided into two sets of six groups of six animals. The first set of mice was used for an early phase assessment. Sixty minutes after the oral drug administration, formalin (1% in NSS, 20 µl) was injected subcutaneously into the right dorsal hind paw of the mice. The time in second that the mice spent for intensive licking the paw was recorded between 0-5 min after formalin injection. In the late phase assessment, the second set of mice was used. Test substances were orally administered to the mice for 40 min before formalin injection. The licking time was recorded between 20-30 min after formalin injection.12

Antipyretic test (yeast-induced hyperthermia in rats)

The antipyretic activity of ML extract was tested and compared with indomethacin using the method described previously13 with slight modification. Male rats weighing 200-210 g were used and divided into three groups of six animals. The rats were subcutaneously injected with 20% yeast in NSS (1 ml/100 g body weight) to induce fever. At 18 h after yeast injection, the temperature was at peak. Only rats with 1°C or more increase in rectal temperature were used and divided into three groups which received vehicle, indomethacin, and ML extract, respectively. The rectal temperatures of rats were recorded at 30 min, 1 h, 2 h and 3 h after drug administration.

Acute toxicity

The procedure was conducted according to the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development guidelines for testing of chemicals.14 Five female rats with 200-210 g body weight were used. The rats were administered with ML extract in a single oral dose of 5000 mg/kg. Signs and symptoms observed after ML extract administration were recorded at 1, 2, 4 and 6 h and then once per day for 14 days.

Statistical analyses

The data from the experiments were expressed as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM). Statistical comparison between groups was analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and post hoc least-significant difference (LSD) test. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Carrageenan-induced hind paw edema in rats

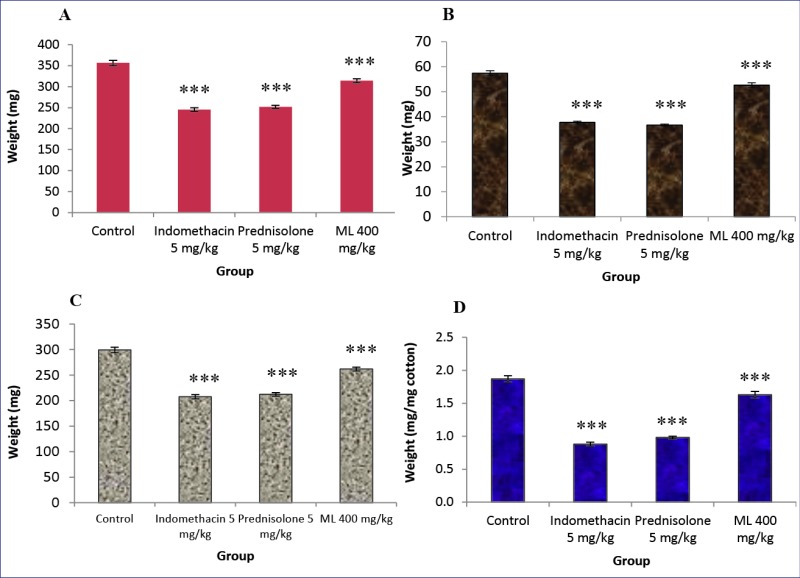

The effect of ML extract against carrageenan-induced hind paw edema is shown in Fig. 1. Indomethacin, a COX–inhibitor at the dose of 10 mg/kg markedly reduced the paw edema caused by carrageenan injection. ML extract, given orally, also significantly reduced the carrageenan-induced edema formation of the rat paw. The anti-edematous effect of ML extract gradually increased as the doses increased.

Fig. 1 .

Effects of ML extract on carrageenan-induced paw edema in rats

Values are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 6).

Significantly different from control: * p< 0.05, ** p< 0.01, and *** p< 0.001.

AA-induced hind paw edema in rats

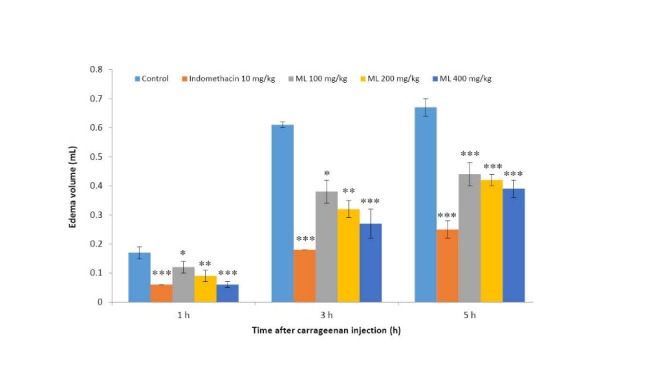

As demonstrated in Fig. 2, indomethacin did not show any significant inhibitory effect in this model. Phenidone, a dual inhibitor of COX and LOX showed significant reduction of the AA-induced rat paw edema. ML extract at all doses tested significantly inhibited AA-induced paw edema in dose dependent manner.

Fig. 2 .

Effects of ML extract on AA-induced paw edema in rats

Values are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 6).

Significantly different from control: *** p< 0.001.

Cotton pellet-induced granuloma formation in rats

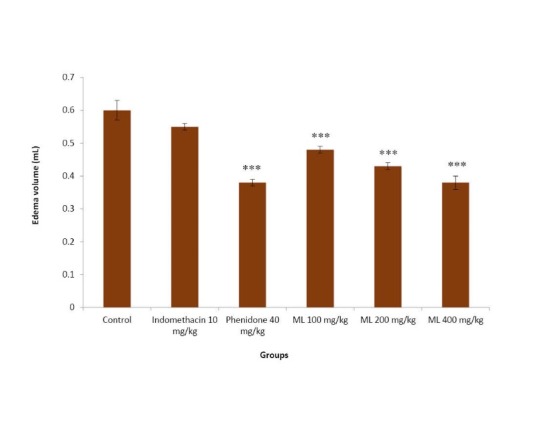

Granuloma formation and transudation

The results in Fig. 3 indicated that indomethacin and prednisolone markedly decreased the transudative weight. ML extract at a dose of 400 mg/kg slightly but significantly lowered the transudative weight. The inhibitory effects of the test drugs on granuloma formation were found to be well correlated with their effect on the transudative weight. Both indomethacin and prednisolone caused profound inhibitory effects on granuloma formation, whereas ML extract slightly, but significantly elicited the inhibitory effect on this parameter.

Fig. 3 .

Effects of ML extract on granuloma wet weight (A), granuloma dry weight (B), transudative weight (C), and granuloma weight (D)of cotton pellet-induced granuloma in rats.

Control received 5% Tween 80 only. Test drugs were orally administered for 7 days. The granuloma tissues were dissected out on the eighth day and weight. Values are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. (n= 6). Significantly different from control: *** p< 0.001.

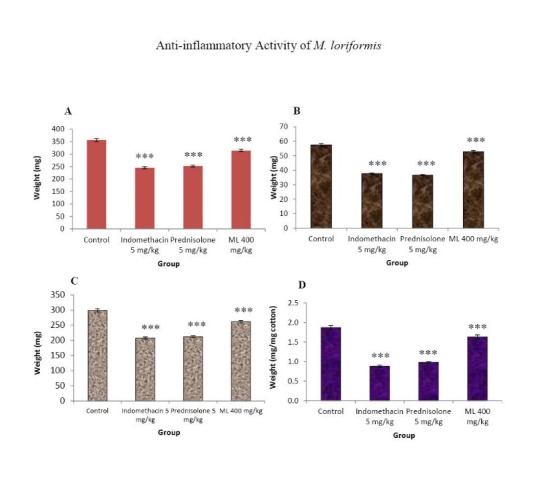

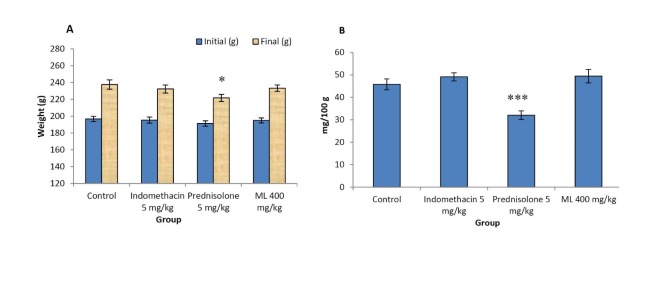

The body weight gain and the thymus weight

The body weight gain and the thymus weights of rats implanted with cotton pellets are presented in Fig. 4. The body weight gain of the control group increased normally. The gain of the body weight and the dry thymus weight in rats treated with indomethacin and ML extract were not significantly different from those of the control group. In contrast, prednisolone significantly reduced both parameters.

Fig. 4 .

Effects of ML extract on body weight (A) and dry thymus weight (B) of cotton pellet-induced granuloma in rats

Values are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 6). Significantly different from control: * p< 0.05, *** p< 0.001.

Alkaline phosphatase activity

Alkaline phosphatase level in the serum of control group after 7 days of the cotton pellet implantation was significantly elevated when compared with that of the normal group (non implanted rats). Oral administration of ML extract and reference drugs, indomethacin and prednisolone daily for seven days normalized the increased alkaline phosphatase level in the serum to normal levels (Table 1).

Table 1 . Effects of ML extract on alkaline phosphatase activity in the serum of cotton pellet-induced granuloma in rats .

| Group |

Dose

(mg/kg) |

Alkaline phosphatase

(units/l) |

Total protein

(g/dl) |

Serum alkaline phosphatase activity (U of enz/mg of serum protein x10 -4 ) |

| Normal | - | 123.87 + 6.63 | 5.67 + 0.29 | 21.94 + 0.96 |

| Control | - | 140.90 + 1.54 | 5.60 + 0.18 | 25.27 + 0.74a |

| Indomethacin | 5 | 112.68 + 3.85 | 5.45 + 0.12 | 20.66 + 0.41b |

| Prednisolone | 5 | 122.70 + 4.74 | 5.88 + 0.14 | 20.92 + 0.97 b |

| ML extract | 400 | 126.18 + 5.54 | 6.00 + 0.23 | 21.05 + 0.53 b |

Values are expressed as mean + SEM (n = 6). asignificant from normal: p< 0.01, b significant from control: p< 0.001

Normal = non-implanted group; Control = implanted group, received 5% Tween 80 only.

Effect on gastric mucosa

As demonstrated in Table 2, indomethacin and prednisolone at the dose of 5 mg/kg significantly caused gastric ulceration. The lesions of the gastric mucosa of rats in the prednisolone-treated group were small ulcers. In contrast, indomethacin produced large and hemorrhagic gastric lesions in two rats, whereas in the other four rats, small ulcers were found. ML extract did not affect the gastric mucosa of the rats when compared with that of the control group.

Table 2 . Effects of ML extract on gastric mucosa .

| Group | Dose (mg/kg) | Ulcer index |

| Control | - | 0 |

| Indomethacin | 5 | 3 ** |

| Prednisolone | 5 | 2 ** |

| ML extract | 400 | 0 |

Values are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 6).

Significantly different from control: ** p< 0.01.

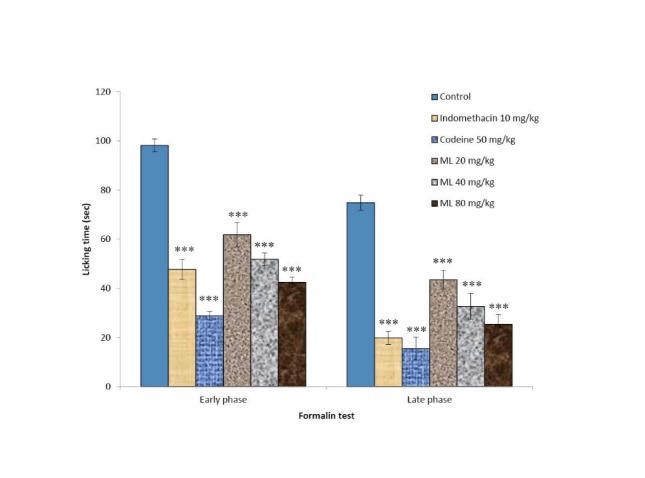

Formalin test

The results in Fig. 5 show that injection of 1% formalin into the dorsal hind paw of mice produced intensive licking on the injected side with marked licking time. Codeine inhibited the licking time in both early and late phases. Indomethacin also showed inhibitory effect on the time the mice spent in paw licking in the early phase and showed a marked effect in the late phase. ML extract at doses of 20, 40, and 80 mg/kg dose-dependently reduced the licking time in both phases when compared to that of the control group.

Fig. 5 .

Inhibitory effects of ML extract on the early phase and late phase of the formalin test in mice Values are expressed as mean ± SEM (n= 6). Significantly different from control: ***p< 0.001.

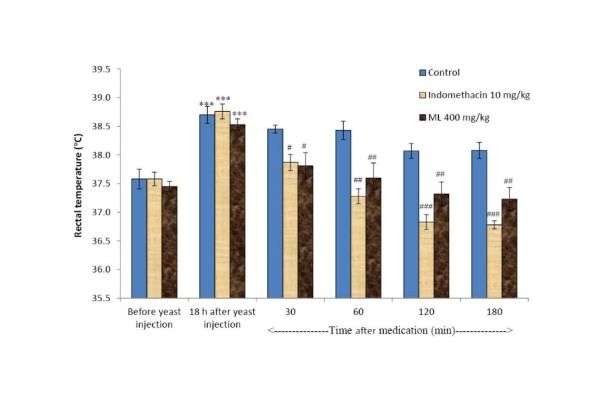

Yeast-induced hyperthermia in rats

The antipyretic effect of ML extract and indomethacin is shown in Fig. 6. Eighteen hours after yeast injection, rectal temperature of all rats raised more than 1 °C. In the control group the rectal temperature was not significantly different during 180 min of assessment. Indomethacin and ML extract at the dose of 400 mg/kg significantly reduced the rectal temperature to normal in 30 min and lasted for 180 min.

Fig. 6 .

Effects of ML extract and indomethacin on yeast- induced hyperthermia in rats Values are expressed as mean ± SEM (n= 6). *** p< 0.001 compared to that before yeast injection. # p< 0.05, ## p< 0.01, ### p< 0.001 compared to the control group (after medication).

Acute toxicity

A single administration of ML extract by oral route at the high dose of 5000 mg/kg produced neither mortality nor any signs of toxicity. No change in general behavior or other physiological activities was observed when compared with those of the control group. At the end of the experiment all rats were sacrificed to examine gross pathological changes, the results showed that there were no detectable abnormalities and no differences between the size and color of the internal organs of the control and ML extract treated group.

Discussion

The results of the present study revealed the anti-inflammatory activity of ML extract. The development of edema in carrageenan-induced paw edema is a biphasic event. The initial phase (1.5-2.5 h) is caused by the release of histamine, serotonin and bradykinin. The second phase is caused by the mediators of COX pathway which are prostaglandins occuring from 2.5-6 h.15,16 The oral administration of ML extract significantly reduced the edema formation of the rat paw from the first hour to the fifth hour of assessment. The possible mechanism of action of ML extract may involve the COX pathway and other inflammatory mediators. The AA-induced paw edema model is sensitive to dual inhibitors of AA metabolism, lipoxygenase inhibitors and corticosteroids, but insensitive to selective COX inhibitors.17 Paw edema produced by AA is caused by the release of leukotrienes.18 ML extract at the dose of 400 mg/kg inhibited significantly the paw edema induced by AA. Indomethacin, the COX inhibitor, did not show any effect on this model. Our findings suggest that the mechanism of anti-inflammatory action of ML extract might be related to the inhibition of both the LOX and COX pathways.

The granuloma formation is a typical feature commonly found in chronic inflammatory process.19 Cotton pellet-induced inflammatory response in rats has been divided into transudative, exudative, and proliferative phases.9,20 ML extract at the dose of 400 mg/kg significantly reduced the granuloma formation and transudation. This result suggests that ML extract also inhibited proliferative phase of chronic inflammation.

Prednisolone significantly reduced the thymus weight and the body weight gain. The loss of body weight gain and the thymus weight in long term prednisolone treatment is due to protein catabolism and lymphoid tissue destruction.21 Indomethacin and ML extract had no effect on both parameters. The results suggest that anti-inflammatory effect of ML extract is non-steroid like action.

It has been known that the lysosomal enzyme such as alkaline phosphatase activity in serum and exudate is elevated during inflammation. This elevation can be normalized by both NSAIDs and steroidal drugs via the stabilization of lysosomal membrane.22 In this study, ML extract could normalize alkaline phosphatase activity in rats implanted with cotton pellet to normal level which may result from the stabilization of the lysosomal membrane.

The texture of the gastric mucosa from ML extract-treated rats was not significantly different from that of the control group. The anti-inflammatory without ulcerogenic effect of ML extract is a clinical desirable characteristic of novel anti-inflammatory agents.

Formalin test in mice is contributed by two distinct phases, the early phase lasting the first 5 min and the late phase lasting from 20 to 30 min after formalin injection. It has been reported that the early phase is due to a direct effect on nociceptors C-fiber (non-inflammatory pain). Drugs acting on CNS such as morphine and codeine can inhibit this phase. The late phase of formalin test relates with an inflammatory response in peripheral tissue as well as functional changes in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord (inflammatory pain).23-25 This phase can be inhibited by NSIADs, steroids and centrally acting drugs.24 In the inflammatory process, peripheral nociceptor was sensitized by prostanoids produced via COX-2 pathway, thereby causing localized pain hypersensitivity.26 ML extract at the doses of 20, 40 and 80 mg/kg inhibited both phases of pain in this model. Analgesic action in the early phase of indomethacin and ML extract may be caused by the reduction of PG production in the CNS. In the second phase, the antinociceptive effect of ML extract may be attributed to inhibition of release and/or synthesis of PGs and other mediators involving in this test.

It has been known that inflammatorystimuli may cause an elevation of body temperature or fever. Fever is a coordination of endocrine, autonomic, and behavioralresponse organized by the brain.27 It was reported that infection causes the cells in the CNS to produce cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6, β-IFN, γ-IFN, TNF-α, which act independently to produce fever.27 These cytokines, in turn, act on blood vessels in the brain to produce PGE2. The elevationof PGE2inside the brain affectsthermoregulatory neurons and resultsin elevation of temperature.28 The antipyretic effect of NSAIDs is due to the inhibition of the synthesis and/or release of PGE2 within the preoptic-anterior hypothalamus.27 ML extract at the dose of 400 mg/kg caused the reduction of rectal temperature which may be resulted from the inhibition of the synthesis and/or release of PGE2.

The acute toxicity study revealed that ML extract did not produce mortality or any signs of toxicity. No pathological change of internal rat organs was noted. These results implied the nontoxic effect of ML extract at the high dose of 5,000 mg/kg body weight.

Conclusion

The obtained results suggest that the ethanol extract of M. loriformis possesses the anti-inflammatory, analgesic and antipyretic activities. It does not produce any abnormality in acute toxicity test in rats. These results support the use of M. loriformis in traditional medicine for inflammation ailments.

Acknowledgements

Financial support of the Center for Innovation in Chemistry (PERCH-CIC), Commission on Higher Education, Ministry of Education, is gratefully acknowledged.

Ethical issues

All procedures involving the animals were in accordance with the approvals of Animal Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand (Registration No: 22/2553).

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Jiratchariyakul W, Vongsakul M, Sunthornsuk L, Moongkarndi P, Narintorn A, Somanabandhu A. et al. Immunomodulatory effect and quantitation of a cytotoxic glycosphingolipid from Murdannia loriformis. J Nat Med. 2006;60:210–16. doi: 10.1007/s11418-006-0040-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jiratchariyakul W, Okabe H, Moongkarndi P, Frahm AW. Cytotoxic glycosphingolipid from Murdannia loriformis (Hassk) Rolla Rao et Kammathy. Thai J Phytopharm. 1998;5:10–20. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jiratchariyakul W, Okabe H, Frahm AW. A steroidal glucoside from Murdannia loriformis (Hassk) Rolla Rao et Kammathy. Thai J Phytopharm. 1996;3:31–39. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cornetta AJ, Russell JP, Cunnane M, Keane WM, Rothstein JL. Cyclooxygenase-2 expression in human thyroid carcinoma and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:238–42. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200202000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eschwege P, de Ledinghen V, Camilli T, Kulkarni S, Dalbagni G, Droupy S. et al. Arachidonic acid and prostaglandins, inflammation and oncology. Presse Med. 2001;30:508–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steele VE, Hawk ET, Viner JL, Lubet RA. Mechanisms and applications of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the chemoprevention of cancer. Mutat Res. 2003;523-524:137–44. doi: 10.1016/S0027-5107(02)00329-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Winter CA, Risley EA, Nuss GW. Carrageenan-induced edema in hind paw of the rat as an assay for antiiflammatory drugs. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1962;111:544–7. doi: 10.3181/00379727-111-27849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DiMartino MJ, Campbell GK Jr, Wolff CE, Hanna N. The pharmacology of arachidonic acid-induced rat paw edema. Agents Actions. 1987;21:303–5. doi: 10.1007/BF01966498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swingle KF, Shideman FE. Phases of the inflammatory response to subcutaneous implantation of a cotton pellet and their modification by certain anti-inflammatory agents. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1972;183:226–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bessey OA, Lowry OH, Brock MJ. A method for the rapid determination of alkaline phosphates with five cubic millimeters of serum. J Biol Chem. 1946;164:321–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Minano FJ, Serrano JS, Pascual J, Sancibrian M. Effects of GABA on gastric acid secretion and ulcer formation in rats. Life Sci. 1987;41:1651–8. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(87)90734-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hunskaar S, Hole K. The formalin test in mice: dissociation between inflammatory and non-inflammatory pain. Pain. 1987;30:103–14. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(87)90088-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Teotino UM, Friz LP, Gandini A, Dellabella D. Thio derivatives of 2,3-dihydro-4H-1,3-benzoxazin-4-one synthesis and pharmacological properties. J Med Chem. 1963;6:248–50. doi: 10.1021/jm00339a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Test No. 420. Acute Oral Toxicity - Fixed Dose Procedure;2001. p. 1-14. doi : 10.1787/20745788.

- 15.Vinegar R, Schreiber W, Hugo R. Biphasic development of carrageenan edema in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1969;116:96–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Di Rosa M, Giroud JP, Willoughby DA. Studies of the acute inflammatory response induced in rats in different sites by carrageenan and turpentine. J pathol. 1971;104:15–29. doi: 10.1002/path.1711040103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DiMartino MJ, Campbell GK Jr, Wolff CE, Hanna N. The pharmacology of arachidonic acid induced rat paw edema. Agents Actions. 1987;21:303–05. doi: 10.1007/BF01966498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fiorucci S, Meli R, Bucci M, Cirino G. Dual inhibitors of cyclooxygenase and 5-lipoxygenase A new avenue in anti-inflammatory therapy? Biochem Pharmacol. 2001;62:1433–8. doi: 10.1016/S0006-2952(01)00747-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ismail TS, Gopalakrishnan S, Begum VH, Elango V. Anti-inflammatory activity of Salacia oblonga Wall and Azima tetracantha Lam. J Ethnopharmacol. 1997;56:145–52. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(96)01523-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Diegelmann RF, Evans MC. Wound healing: an overview of acute, fibrotic and delayed healing. Front Biosci. 2004;9:283–9. doi: 10.2741/1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Boyd JR. Drug facts and comparison. Missousi: JB Lippincott; 1982. p 33-99.

- 22.Salmon JA, Higgs GA. Prostaglandins and leukotrienes as inflammatory mediators. Br Med Bull. 1987;43:285–96. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a072183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hunskaar S, Faster OB, Hole K. Formalin test in mice, a useful technigue for evaluating mild analgesics. J Neurosci Meth. 1985;14:69–76. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(85)90116-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hunskaar S, Hole K. The formalin test in mice: dissociation between inflammatory and non-inflammatory pain. Pain. 1987;30:103–14. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(87)90088-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tjolsen A, Berge OG, Hunskaar S, Rosland JH, Hole K. The formalin test: an evaluation of the method. Pain. 1992;51:5–17. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90003-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Samad TA, Moore KA, Sapirstein A, Billet S, Allchorne A, Poole S. et al. Interleukin-1beta-mediated induction of Cox-2 in the CNS contributes to inflammatory pain hypersensitivity. Nature. 2001;410:471–5. doi: 10.1038/35068566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ganong WF. Functions of the nervous system: central regulation of visceral function. In: Ganong WF, editor. Review of medical physiology. 20th ed. New York: Mc- Grew-Hill; 2001. p 245-47.

- 28.Blatteis CM, Sehic E, Li S. Pyrogen sensing and signaling: old views and new concepts. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31 Supp l5:S168–77. doi: 10.1086/317522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]