Abstract

Proper and early identification of patients who harbor serious occult illness is the first step in developing a disease-management strategy. Identification of illnesses through the use of noninvasive techniques provides assurance of patient safety and is ideal. PA dilation is easily measured noninvasively and is due to a variety of conditions, including pulmonary hypertension (PH). The clinician should be able to thoroughly assess the significance of PA dilation in each individual patient. This involves knowledge of the ability of PA dilation to accurately predict PH, understand the wide differential diagnosis of causes of PA dilation, and reverse its life-threatening complications. We found that although PA dilation is suggestive of PH, data remain inconclusive regarding its ability to accurately predict PH. At this point, data are insufficient to place PA dilation into a PH risk-score equation. Here we review the causes and complications of PA dilation, define normal and abnormal PA measurements, and summarize the data linking its association to PH, while suggesting an algorithm designed to assist clinicians in patient work-up after recognizing PA dilation.

Keywords: pulmonary arterial hypertension, pulmonary artery enlargement, pulmonary artery diameter

Pulmonary artery (PA) dilation is an increasingly common cause of medical consultation. This is likely due to the frequent acquisition of imaging studies in patients with respiratory symptoms (1, 2) and augmented awareness of the association between PA size and pressures. Identification of PA dilation on computed tomography (CT) of the chest performed to assess patients with nonspecific cardiorespiratory symptoms may raise the possibility of pulmonary hypertension (PH).

Although a dilated PA may be seen on plain radiography, the use of more advanced technologies such as CT of the chest and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) allow for more accurate measurement of the PA size, without the distraction of superimposed hilar and mediastinal structures. The use of cross-sectional imaging on CT or MRI to measure PA size yields thin sectioned and reproducible standardized images, even in patients with lung hyperinflation or large body habitus (3). Several studies have tested whether the size of the PA by CT (4–11) or MRI (12–14) predicts PH. However, PH is just one of many causes of a dilated PA, and with the increasing use of noninvasive imaging for its ever-expanding indications, physicians will likely see a concurrent increase in the incidental recognition of PA enlargement.

There are a large number of causes of PH, which have been classified in five groups by the fifth World Symposium on Pulmonary Hypertension (I, pulmonary arterial hypertension [PAH]; II, PH associated with left heart diseases; III, PH associated with lung diseases and/or hypoxia; IV, PH due to chronic thrombotic and/or embolic disease; and V, miscellaneous) (15). Early detection of PH is essential, given the prognostic implications of this diagnosis and the availability of effective treatments (16). However, despite the increased awareness of this condition (17), there continues to be a marked delay in its diagnosis, because the presenting symptoms are shared with other more common respiratory or cardiovascular diseases (18–20). The characteristic increase in PA pressure induces vascular remodeling in the form of wall thickening and dilation, changes that are often detected with noninvasive imaging (21, 22). Consequently, an enlarged PA has emerged as one of the early findings suggesting the presence of PH in different conditions.

In this review we examine the criteria for diagnosis and describe the potential causes, mechanisms, and implications of PA dilation. Furthermore, we propose and algorithm for the evaluation of PA dilation. Most of the information presented derived from studies that used CT to assess the PA size. We particularly focused on PH, given that the bulk of literature predominantly addressed this association and/or tested the ability of a dilated PA to predict the presence of PH.

Normal PA Size

Before the recent publication of population-based data from a cohort of the Framingham Heart Study (23), most data used to establish normative reference ranges for PA size were based on relatively small-size studies (4–7, 23–25). The Framingham investigators reviewed the noncontrasted chest CT scans from 706 individuals who were deemed “healthy” (defined by the lack of obesity, hypertension, or history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD], pulmonary embolism, or cardiovascular disease) and found a mean (SD) main PA diameter of 25.1 (2.8) mm, with an upper limit of normal (90th percentile used as a cut-off value) of 28.9 mm in men and 26.9 mm in women (23). Interestingly, at PA diameters greater than the 90th percentile, a significantly higher number of subjects (26 vs. 20%, P = 0.01) reported dyspnea on exertion.

A few small studies provided information on the PA diameter of subjects without evidence of PH (“control group”) on right heart catheterization or echocardiography (4, 5, 24, 25). In general, these subjects had no cardiopulmonary diseases or significant comorbidities. In one of the earliest studies of this kind, Kuriyama and colleagues studied 26 healthy control subjects and noted a mean (SD) main PA diameter of 24.2 (2.2) mm (4). Edwards and colleagues studied 100 individuals without cardiac or thoracic disease using more modern CT equipment with unenhanced imaging. The mean (SD) main PA diameter of the individuals without PH was 27 (3) mm (men, 27.7 mm and women, 26.4 mm) (24). Reasons for the differences in diameter observed in these studies were attributed to the measuring methodology, window settings, use of contrast medium, underlying medical conditions, and demographic characteristics. Similarly, other small studies found a “normal” PA diameter in the range of 19.5 to 32.6 mm based on predictability of PH (5–7, 25, 26). For the most part, studies did not report whether the entire vessel diameter (including all vessel wall layers) or the vascular lumen was measured. Furthermore, there was considerable variation in the use of intravenous contrast.

A few studies have suggested a strong association between the ratio of main PA diameter to ascending aortic diameter and PA pressure (4, 9, 12, 14, 27). Adjusting for the aortic diameter is in effect correcting for body surface area, sex, age, phase of the cardiac cycle, and other technical factors (“internal normalization”) (23, 27). Data from the Framingham Heart Study showed that in healthy subjects the ratio of mean (SD) PA to ascending aorta diameter was 0.77 (0.09), with a 90th percentile cut-off value of 0.91. The main PA over aortic diameter is significantly greater in patients with PH compared with control subjects (14). This ratio better predicted the mean PA pressure (mean PA pressure = 3.7 + 24 × main PA diameter/aortic diameter) than the diameter of the main PA or the diameter of main PA over body surface area (14). A retrospective analysis of 50 patients with pulmonary and cardiovascular diseases found that a ratio of main PA to ascending aorta diameter greater than 1 is associated with a mean PA pressure of 20 mm Hg or above, with a sensitivity of 70%, specificity of 92%, and positive predictive value of 96% (27).

Technical Aspects in the Measurement of PA Size

Potential sources of error include differences in age, sex, body surface area, image slice thickness, CT window width and level, method of measurement (at the level of pulmonary bifurcation or right PA), difficulties in identifying vessel interfaces, use of intravenous contrast (may transiently affect the PA diameter by affecting vascular tone, cardiac output, and/or heart rate), inclusion of arterial wall in the measurements (external limits or internal lumen), and period of the cardiac cycle (systole or diastole) when images are obtained (3, 4, 24, 27). Some investigations found a direct association between the mean PA diameter and body surface area (27), and others did not (9). Dividing the main PA by the aortic diameter measured at the same level of the chest and during the same phase of the cardiac cycle adjusts for most of these potential differences (14). Nevertheless, if there are major aortic abnormalities, this ratio becomes unreliable (27). A group of investigators studied whether the use of the mid-anteroposterior diameter of the thoracic vertebra was appropriate to adjust for body size. Unfortunately, this adjustment was inferior to the normalization using the aorta diameter (10). Other investigators have adjusted the diameter of PA branches by the adjacent airway size (artery-bronchus ratio), a method that has improved the specificity for detecting PH in a few studies (7, 8).

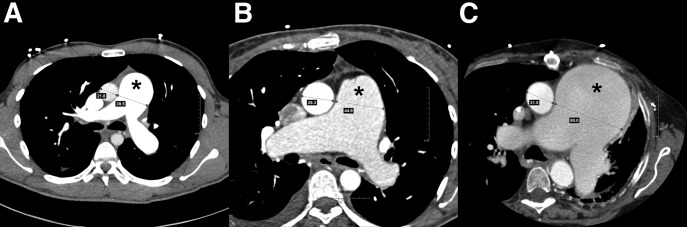

The measurements of the main PA and ascending aorta diameters are made at the level of the PA bifurcation (ideally when both the right and left PA appear to be of similar size) using electronic calipers (Figure 1). We use 64- or 128-section scanners. Scans are obtained on patients in supine position with breath holding at full inspiration. The acquisition parameters and use of intravenous contrast agents vary depending on the indication of the study. Basic acquisition parameters used are: 120 kVp with mAs selected from the reference range (80, 100, or150), pitch of 1.0 with 0.5-second rotation time. We reconstruct scans at section widths of 1 mm (high-resolution CT and pulmonary embolism studies) or 3 mm (regular CT) at 1- and 1.5-mm intervals, respectively. The images are analyzed using mediastinal windows (window width, 400; window center, 40). The axial diameter of the main PA is measured at the level of the PA bifurcation, along the line that originates from the center of the adjacent aorta and is perpendicular to the long axis of the PA (9). The PA diameter includes the vessel wall in noncontrasted studies and the vascular lumen in contrasted CT.

Figure 1.

Dilated pulmonary artery (PA, indicated by the asterisk in each panel) on contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the chest. (A) A 22-year-old man with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). Mean PA pressure 83 mm Hg and pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) 18.3 Wood units. Aorta and PA measure 21.8 and 39.5 mm, respectively. (B) A 46-year-old woman with PAH due to congenital heart disease had a ventricular septal defect corrected at the age of 5 years. Right heart catheterization at the time of CT scan showed mean PA pressure of 55 mm Hg with a PVR of 12 Wood units. Aorta and PA measure 29.3 and 44.9 mm, respectively. (C) A 64-year-old woman with chronic thromboembolic portopulmonary hypertension after pulmonary thromboendarterectomy. Due to severe (80%) extrinsic compression of the left main coronary trunk she required percutaneous coronary intervention with stent placement. Mean PA pressure 55 mm Hg and PVR 7.5 Wood units. Aorta and PA measure 31.5 and 80.0 mm, respectively.

Causes of Dilated PA

The differential diagnosis of causes of dilated PA is wide (Tables 1 and 2) and likely involves a “two-hit” model with a genetic predisposition and long-term exposure to abnormal pulmonary hemodynamics, hypoxia, atherosclerosis, or certain diseases (28). PH is possibly the most common contributing factor to a dilated PA (29). Patent ductus arteriosus, atrial and/or ventricular septal defects may result in left-to-right shunting, yielding increased PA blood flow and shear stress that lead to PA dilation. In the case of patent ductus arteriosus, the constant “jet stream” of blood into the PA causes local injury at the point of impact (30). This may in turn increase the risk of endovascular seeding and subsequent mycotic aneurysm formation (31). Bicuspid pulmonic valve stenosis is associated with larger mean PA due to post-stenotic turbulent blood flow patterns and increased wall shear stress (32). Furthermore, larger main PA and aortic dimensions may be seen in patients with a bicuspid aortic valve, which may indicate an underlying genetic connective tissue predisposition (33).

Table 1.

Known causes of main dilated pulmonary artery

| Causes |

|---|

| Pulmonary hypertension |

| Pulmonary arterial hypertension |

| Thromboembolic disease (acute or chronic) |

| Eisenmenger syndrome |

| High altitude |

| Schistosomiasis |

| Increased or turbulent blood flow |

| Left-to-right shunting |

| Patent ductus arteriosus |

| Atrial septal defect |

| Ventricular septal defect |

| Valvular pulmonic stenosis |

| Arteriovenous malformation |

| Congenital |

| Infectious |

| Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia |

| Rheumatologic/vasculitis |

| Behçet disease |

| Hughes-Stovin syndrome |

| Takayasu arteritis |

| Connective tissue disease |

| Marfan syndrome |

| Loeys-Dietz syndrome |

| Ehlers-Danlos syndrome |

| Cystic medial necrosis |

| Infectious |

| Tuberculosis |

| Syphilis |

| Bacterial |

| Trauma |

| Blunt |

| Penetrating |

| Idiopathic |

Table 2.

Characteristic findings in different causes or illnesses associated with dilated pulmonary artery

| Cause | Mechanism | Clinical Signs | Characteristic Imaging |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pulmonary hypertension | |||

| PAH | Increased pulmonary vascular resistance by endothelial and smooth muscle cell proliferation (78) | Loud P2, sternal heave, hepatomegaly, jugular venous distension, edema | Dilated central PA with rapid tapering to peripheral vessels, vascular pruning (39). Mosaic pattern of lung attenuation. |

| Thromboembolic disease (acute or chronic) | Increased pulmonary artery pressure from thrombus load (acute) or fibrous stenosis (chronic) (79) | Hypoxia, increased A–a gradient, hemoptysis | PA filling defects, irregularities, bands and webs. |

| Eisenmenger syndrome | Vascular remodeling from longstanding increased flow (80) | Cyanosis, clubbing, loud P2 | Peripheral PA pruning and neovascularity. |

| High altitude | Sustained alveolar hypoxia (81) | Nonspecific (exertional dyspnea), polycythemia, hypoxemia | Dilation of central PA and smaller arterial vessels. |

| Schistosomiasis | Chronic inflammation/immunological reaction with vascular remodeling (82) | Nonspecific (exertional dyspnea and PAH signs) | Dilation of the pulmonary trunk. |

| Increased or turbulent blood flow | |||

| Left-to-right shunt (PDA, ASD, VSD) | Increased blood flow and hemodynamic stress | Continuous machine-like murmur (PDA), fixed split of S2 (ASD), pansystolic murmur (VSD) | PA may approach aneurysmal size. Increased pulmonary vascularity that extends to the periphery of the lung fields. |

| Pulmonic valve stenosis | Post-stenotic flow pattern leads to increase wall shear stress (32, 83) | Delayed S2, systolic ejection murmur increased on inspiration | Post-stenotic PA dilation. |

| Arteriovenous malformations | High pulmonary flow | Asymptomatic or dyspnea, hypoxemia, hemoptysis, or cerebrovascular accidents | Well demarcated lung nodule(s) with taillike extension (supplying artery and draining vein). |

| Vasculitis | |||

| Behçet disease | Chronic vasculitis | Recurrent oral and genital ulcers, uveitis, hemoptysis | PA aneurysms in large proximal branches, pulmonary infarction, pneumonia, organizing pneumonia (39). |

| Hughes-Stovin syndrome | Chronic vasculitis | No oral or genital ulcers, no uveitis or skin lesions (39, 42) | PA aneurysm-thrombosis combination. Like Behçet, prone to rupture (22, 39). |

| Takayasu arteritis | Large vessel granulomatous vasculitis | Arm or leg claudication (“pulseless disease”), renal artery stenosis, Raynaud phenomenon | Narrowing of the aorta and/or main branches with thickening of the vascular wall. |

| Connective tissue disease | |||

| Marfan syndrome | Abnormal microfibrils from mutated fibrillin-1 gene | Various musculoskeletal manifestations, murmur of aortic regurgitation | Aortic dilation and/or dissection. May have pulmonary root involvement (38, 40). |

| Loeys-Dietz syndrome | Missense mutation of TGFBR1, TGFBR2, or SMAD3 genes (37) | Hypertelorism, cleft palate, club foot, craniosynostosis, vascular dilation and tortuosity (37) | Aortic aneurysm (39). May affect vessels other than the aorta. |

| Ehlers-Danlos syndrome | Disarray of collagen biosynthesis | Hyperextensible skin, hypermobile joints with frequent dislocations, tissue fragility (84) | Aneurysm of the iliac, splenic, or renal arteries (22). |

| Cystic medial necrosis | Disruption of smooth muscle, elastin, and collagen in vascular media (85) | Often present in Marfan and Ehlers- Danlos syndromes (85) | Dilation of large arteries, particularly the aorta. |

| Infectious | |||

| Pyogenic bacteria, syphilis, tuberculosis, fungi | Bacteremia with septic emboli or spread from adjacent pneumonia or lymphatics (39) | Various presentations of infectious diseases, endocarditis | Indolent infections often with true aneurysms, virulent organisms often with pseudoaneurysms (39). |

| Others | |||

| Trauma | Trauma from chest tube or pulmonary artery catheter | Asymptomatic to hemoptysis | Pseudoaneurysm from blood contained within adventitia (22). |

| Idiopathic | Unknown | Asymptomatic | May approach aneurysmal size (86, 87). |

Definition of abbreviations: ASD = atrial septal defect; P2 = pulmonic component of the second heart sound; PA = pulmonary artery; PAH = pulmonary arterial hypertension; PDA = patent ductus arteriosus; S2 = second heart sound; VSD = ventricular septal defect.

Patients with pulmonary hypertension may have dilated right ventricle and right atrium when compared to left side chambers. In addition, these patients may also have a smaller angle between the interventricular septum and the horizontal line or deviation of the interventricular septum toward the left (11). A vascular cause of the mosaic pattern is suggested when large-caliber vessels are surrounded by high attenuation areas and small-caliber vessels by low attenuation zones (88).

Less common causes of dilated PA include rheumatologic or vasculitic illnesses (the majority of which are from Behçet disease), connective tissue diseases, or infections. Behçet disease is a chronic multisystem vasculitis characterized by recurrent oral and genital ulcerations, eye and skin lesions, and inflammation of small, medium, or large blood vessels (34, 35). Of the many pulmonary manifestations of Behçet disease, PA aneurysm is the most common (35, 36).

Certain connective tissue diseases have been implicated in PA dilation; nevertheless, the exact prevalence is not known, and mechanisms are poorly understood (37–39). Marfan syndrome traditionally affects the aorta; however, increased diameters of the main PA have also been reported (38–40). In a study of 50 patients with Marfan syndrome who underwent MRI, the mean main PA diameter was 38.4 mm (38). Interestingly, patients with Marfan syndrome who had undergone elective aortic root replacement had significantly larger PA diameters than the nonoperated ones (38).

Syphilis and tuberculosis were common causes of PA dilation before the introduction of effective antibiotic therapies. Chronic progressive tuberculosis may lead to the formation of a Rasmussen aneurysm (31), which is a vascular aneurysm due to pathological replacement of portions of the vessel with granulomatous tissue (31). Mycotic aneurysms may develop from spread of adjacent pneumonia or from intravascular bacterial seeding.

Mechanism of Dilated PA in PH

Laplace’s law informs us that wall tension (T) is directly proportional to intravascular pressure (P) and radius (R), whereas T = P × R. This formula explains why PA dilations may approach very large sizes even in patients with low PA pressures (41–43).

The association between PA dilation and PH is well known, and dilation has been documented in patients across all groups of PH (3, 5, 7, 43–46). The increased intrapulmonary pressures lead to vascular remodeling, which includes vascular thickening and dilation to cope with increased vascular wall shear stress (47). Pulmonary arterial thickening and stiffening is largely mediated by increased collagen and elastin deposition (48–52). Limited information exists describing the intricate mechanisms of PA dilation at the cellular level in patients with PH. Mechanisms described include phenotypic alterations of resident smooth muscle cells and adventitial fibroblast migration to the intima and media (53). Adventitial fibroblasts have been shown to migrate, transdifferentiate, and proliferate in hypoxic conditions as well as release factors that regulate smooth muscle cell tone and growth (54, 55). Therefore, the adventitia layer is important in cell activation and vascular remodeling in hypoxia-induced PH (28).

Factors that affect the size of the main PA are complex and not only depend on the intravascular pressure. Other causes include age, sex, body constitution, blood flow, vessel compliance, vascular pathology, duration of PH, and interstitial lung disease (3, 4, 9, 13, 14, 27, 43, 56, 57). The dilation of the PA may occur in the absence of PH, in conditions such as in diffuse pulmonary fibrosis (7, 8, 27, 58, 59) and congenital bicuspid valve. In patients with pulmonary fibrosis, a few studies (7, 58, 59) found a lack of association between mean PA pressure and main PA diameter. The PA dilation in pulmonary fibrosis was initially related to the traction effect of pulmonary fibrosis on the PA (59), but a subsequent investigation found no association between PA diameter and total lung capacity or the extent of fibrosis noted at CT (58). Patients with a congenital bicuspid aortic valve have less fibrillin-1, an enzyme essential for formation of elastic fibers in the aorta and PA (60).

Predictability across Different Groups of PH

Although larger PA diameters seem to increase the likelihood of having PH, and smaller diameters suggest its absence, there is a wide range of overlap in between. Although Mahammedi and colleagues (9) found no difference in mean PA diameter among different etiologies of PH, the radiographic presentation of PH may vary depending on the underlying disease, and a degree of main PA dilation in one condition (e.g., idiopathic PAH) may not be easily comparable to another (e.g., interstitial lung disease, mitral stenosis, etc.) (27, 57).

Group I: PAH

Most of the studies that assess the PA size in patients with PH included patients from different groups, and most of the time group I was underrepresented (Table 3). These relatively small studies included a variable proportion of patients with PH, and different cut-offs were selected. In general, the comparison group included patients without PH but with other diseases that motivated the CT of the chest. Hence, the sensitivities and specificities to detect PH showed a wide variation.

Table 3.

Sensitivity and specificity of different pulmonary artery diameter cut-offs for identifying pulmonary hypertension

| Study | PH [Patients/ Total (%)] | WHO Group of PH | Mode of PH Diagnosis | Size of PA* (mm) | Imaging (Contrast) | Vessel Parameter Measured† | SN (%) | SP (%) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kuriyama et al. (4) | 11/27 (41) | Mixed | RHC | 28.6 | CT (V) | External (density profile) | 69 | 100 | Vessels measured using a CT density profile of the artery and adjacent tissues |

| A mean PA pressure > 18 mm Hg was considered PH | |||||||||

| Tan et al. (7) | 36/45 (80) | 3 | RHC | 29.0 | CT (V) | NA | 87 | 89 | PPV very high because studied population included mostly those with PH (four times as many patients as control subjects) |

| A PA diameter of 29.0 mm + ABR > 1.1 had a specificity of 100% | |||||||||

| Edwards et al. (24) | 12/112 (11) | 1 | RHC | 33.2 | CT (N) | External | 58 | 95 | Unenhanced CT (external diameter of vessel measured) |

| Ng et al. (27) | 37/50 (74) | Mixed | RHC | 30.0 | CT (V) | Variable | 68 | 100 | PH was considered as a mean PA pressure ≥ 20 mm Hg |

| Pérez-Enguix et al. (8) | 34/59 (58) | 3 | RHC | 29 | CT (V) | NA | 65 | 61 | Clinical diagnoses were predominantly emphysema, pulmonary fibrosis, and cystic fibrosis |

| Alhamad et al. (63) | 37/63 | 3 | RHC | 25 | CT (V) | External | 86 | 41.2 | Mixed cohort did not include patients with interstitial lung disease |

| 15/19 | Mixed | RHC | 31.6 | CT (V) | External | 47 | 93 | ||

| Lange et al. (5) | 26/78 (33) | Mixed | RHC | 29.0 | CT (V) | NA | 77 | 62 | Included patients with mean PA pressure of 21–24 mm Hg |

| Mahammedi et al. (9) | 298/102 (75) | Mixed | RHC | 29.5 | CT (V) | Variable | 71 | 79 | A main PA over aortic diameter > 1 has a sensitivity and specificity for detecting PH of 71 and 77%, respectively |

| McCall et al. (6) | 32/48 (66.7) | 1, 3 | RHC | 30.8 | CT (NA) | NA | 81.3 | 87.5 | Included patients with scleroderma and several with unidentified connective tissue disease |

| Burger et al. (26) | 37/100 (37) | Mixed | ECHO | 30.0 | CT (N) | External | 78 | 91 | Unenhanced CT |

| Sanal et al. (89) | 51/190 (27) | 4 | ECHO | 28.6 | CT (Y) | NA | 75 | 75 | Only studied patients with acute pulmonary embolism |

| Estimate RVSP for considering PH was 50 mm Hg |

Definition of abbreviations: ABR = artery to bronchus ratio; CT = computed tomography; ECHO = echocardiography; N = no; NA = not available; PA = pulmonary artery; PH = pulmonary hypertension; PPV = positive predictive value; RHC = right heart catheterization; RVSP = right ventricular systolic pressure; SN = sensitivity; SP = specificity; WHO = World Health Organization; V = variable (some patients received contrast while others did not); Y = yes.

Cut-off value selected by the investigators, above which predicted the presence of PH.

Internal (lumen) or external (entire vessel) diameter.

Boerrigter and colleagues studied 51 patients with PA hypertension and 18 subjects with normal PA pressures who had right heart catheterization and cardiac MRI (43). The PA diameter was significantly larger in patients with PH, and the main PA diameter was significantly associated with mean PAP pressure. A ratio of main PA to aorta diameter greater than 1 had a sensitivity of 92%, a specificity of 72%, and a positive predictive value of 92% for PH. Interestingly, during follow-up the PA diameter significantly increased, even in patients in whom the PA pressures decreased (43).

Group II: PH Associated with Left Heart Diseases

There are limited data examining PA diameter in PH due to left heart disease. Yu and colleagues analyzed 550 patients with congestive heart failure who underwent echocardiography to evaluate for pericardial effusion (61). Mean PA diameter on ultrasound was found to be an independent predictor of pericardial effusion; however, it was not associated with greater mortality.

Group III: PH Associated with Lung Diseases and/or Hypoxia

Several studies have evaluated the role of CT scan in predicting PH specifically in patients with parenchymal lung disease. A small study of 55 patients who underwent unenhanced CT and right heart catheterization before heart or lung transplantation found a PA diameter of less than 21 mm to predict normal PA pressures with 95% accuracy; nevertheless, normal PA pressures were found in patients with a main PA diameter as large as 36 mm (3).

Patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis who develop PH have worse survival (62). Tan and colleagues studied patients with PH with interstitial lung disease (ILD) (n = 20), pulmonary vascular disease (chronic thromboembolic portopulmonary hypertension [CTEPH], portopulmonary and idiopathic PAH) (n = 12) and healthy control subjects (n = 9). Mean PA diameter was a strong predictor of PH, but there was no significant association between PA pressure and diameter (7). This relationship was later studied in 65 patients with advanced ILD. Zisman and colleagues found no difference in main PA diameter between patients with and without PH, and the mean PA pressure was not associated with the extent of parenchymal changes (59). Alhamad and colleagues prospectively reviewed the CT scans and right heart catheterization measurements of 100 patients with ILD and noted that PA diameter was a poor predictor of PH in these subjects (63). Pérez-Enguix and colleagues (8) observed a relatively low sensitivity and specificity of PA diameter in patients with parenchymal lung disease, including pulmonary fibrosis. Based on these studies, it is reasonable to conclude that main PA diameter is not a reliable method of diagnosing or screening for PH in patients with ILD. This may not be true for patients with scleroderma-related ILD, because McCall and colleagues found that the main PA diameter was associated with the mean PA pressure in these patients (6).

A PA enlargement in patients with COPD, defined as a ratio of main PA to aorta diameter greater than 1, was associated with severe exacerbations of COPD and the need for hospitalizations (64). This likely identified patients with pulmonary vascular disease and limited capacity to tolerate causes of acute exacerbations (64). Haimovici and colleagues evaluated 35 individuals with chronic lung disease and pulmonary vascular disease. In these patients, main PA diameter did correlate with mean PA pressure but could only predict mean PA pressure within 5 mm Hg in less than half of the population studied (3). Moore and colleagues studied the same relationship in 18 patients with pulmonary vascular disease (idiopathic PAH and CTEPH) and chronic lung disease and were unable to find any statistically significant association between main PA diameter and mean PA pressure (56).

PH can be observed in patients with bronchiectasis (65). Devaraj and colleagues retrospectively reviewed the CT scans of 91 patients with bronchiectasis and found that a greater averaged diameter of the left and right main PA was strongly associated with increased mortality (66). Severe PH has been associated with mortality in patients with obstructive sleep apnea (67) and individuals with severe obstructive sleep apnea have a greater right descending PA diameter measured on chest X-ray (68).

Group IV: CTEPH

Main PA diameter on CT has been shown to correlate with mean PA pressure in CTEPH (69). Żyłkowska and colleagues retrospectively analyzed the PA diameter in 264 patients who had either PAH or CTEPH (46). PA dilatation was found to be an independent risk factor for unexpected death in both PAH and inoperable CTEPH (46). Heinrich and colleagues retrospectively evaluated CT scan findings and hemodynamic measurements in 60 patients with CTEPH who underwent pulmonary thromboendarterectomy (44). Interestingly, main PA diameter on CT correlated with preoperative mean PA pressure but was not associated with postoperative hemodynamic improvement. Schmidt and colleagues compared CT scans before and after pulmonary thromboendarterectomy. They found that mean PA pressure before surgery correlated best with main PA diameter. In addition, PA diameter was the CT determination with the most significant reversibility after surgery; nevertheless, the PA remained enlarged (>28 mm) in the majority of patients (70). A recent larger retrospective study of 114 patients with CTEPH who underwent pulmonary thromboendarterectomy did find main PA diameter to be associated with increased 30-day mortality as well as postoperative clinical worsening on follow-up (71).

Group V: PH Due to Unclear Multifactorial Mechanisms

Patients with sarcoidosis who develop PH have a worse prognosis than those with normal PA pressures (72). In a cohort of 251 patients with sarcoidosis, a greater main PA diameter to ascending aorta diameter ratio and extent of pulmonary fibrosis were found to be associated with increased mortality; however, hemodynamics from right heart catheterization were not incorporated in this cohort (45).

Complications Associated with Dilated PA

A dilated PA could be life threatening, especially in those with elevated PA pressures. A fairly large retrospective study (n = 264) found a PA diameter of 48 mm to be an independent risk factor for unexpected death in patients with PAH or CTEPH (46). The risk of death was highest in patients in whom PA dilation overlapped with very high PA pressures and heart rate. Mechanisms for death were numerous and not limited to left main coronary compression, PA dissection, and/or rupture with cardiac tamponade (46).

Extrinsic compression of the left main coronary artery (LMCA) is well documented in patients with dilated PA, and its risk of occurrence correlates with elevated PA pressures and PA size (21, 73, 74). Compression of the LMCA can manifest as chest pain, left ventricular dysfunction, arrhythmias, and, less commonly, sudden death (75). The exact incidence of LMCA compression in patients with a dilated PA is unclear, but ranges between rare to as high as 19 to 44% (74, 76, 77). Its management involves aggressive treatment of PAH and in certain cases stenting of the LMCA.

Evaluation and Diagnostic Work-up

The fifth World Symposium on Pulmonary Hypertension does not include the PA diameter or the PA/aorta diameter ratio in the algorithm for PH diagnosis (19). However, the literature on the PA diameter in PH is rapidly growing, and we cannot ignore the fact that chest radiologists are certainly more aware of the association. Therefore, not uncommonly the reports of the CT of the chest contain a phrase similar to “dilated PA, consider the presence of PH.” In the right context, statements like this certainly lead to further investigations (i.e., echocardiogram and/or a consult with a physician who has expertise in this condition).

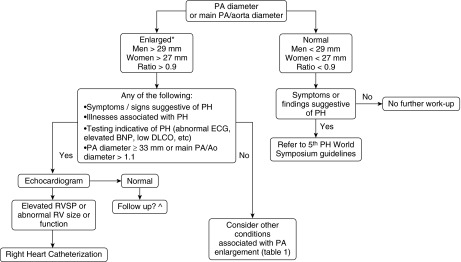

There are no algorithms that help with the evaluation of patients with dilated PA. For this reason, we propose the approach shown in Figure 2. Two concepts need to be underscored. First, this algorithm is not applicable to patients with ILD. Second, the cut-off points for considering PA dilation in Figure 2 are derived from a large study on “healthy” individuals (90th percentile) (23). This is a conservative cut-off that is lower than the one suggested (29–30 mm) in the majority of studies presented in Table 3. In general, these studies did not take into account sex differences and included patients with a variety of comorbidities. As the cut-offs for the PA diameter and the ratio of main PA to aorta diameter increase, the specificity to predict PH improves and therefore may motivate a more aggressive diagnostic approach (Figure 2). Further research may help better define the cut-offs that achieve the best relationship between sensitivity and specificity.

Figure 2.

Algorithm for evaluation of dilated pulmonary artery (PA) in adult patients without interstitial lung disease. *We used the PA diameter cut-offs of 29 mm for men and 27 mm for women, following the upper limit of normal (90th percentile) proposed by the Framingham investigators (23). A ratio of main PA to aorta diameter cut-off of 0.9 is supported by the same study (23). A PA diameter cut-off of 33 mm and ratio of main PA to aorta diameter of greater than 1.1 had a specificity of 95 and 92%, respectively, for detecting pulmonary hypertension (PH) (24, 43). ^No recommendations are made regarding the frequency and method for follow-up, given the absence of data. Ao = aorta; BNP = brain natriuretic peptide; DlCO = diffusing capacity of carbon monoxide; RV = right ventricle; RVSP = right ventricle systolic pressure.

We suggest first considering conditions that are associated with dilated PA. If PH is suspected, an echocardiogram should be the next investigation. If this investigation shows findings suggestive of PH (dilated and/or dysfunctional right ventricle and/or elevated right ventricular systolic pressure), then we would continue with the algorithm suggested by the fifth World Symposium on Pulmonary Hypertension, where right heart catheterization is performed to confirm the diagnosis and other tests are ordered to identify conditions associated with PH (19). If the echocardiogram is normal, other less common causes of a dilated PA need to be considered (Table 2).

Conclusions

A normal PA diameter has been suggested to be less than 29 mm for men and less than 27 mm for women. PA dilation is associated with many illnesses; however, PH is the most common cause. Studies testing the ability of PA dilation to predict PH show wide variability in sensitivity and specificity. More importantly, there is a paucity of data showing the clinical significance of PA dilation. Management of a dilated PA is individualized, but work-up usually begins with echocardiography, followed by right heart catheterization to confirm the diagnosis. There are no studies at the present showing whether PA diameter decreases with treatment of PH or if a smaller diameter after treatment correlates with improved morbidity and mortality.

Footnotes

Supported by National Center for Research Resources, a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) CTSA KL2 grant TR000440 (A.R.T.) and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research.

Author Contributions: T.E.R. participated in the conception and design of the study, writing and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, and final approval of the manuscript submitted. J.E.K. and R.Y. participated in the writing and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content and final approval of the manuscript submitted. A.R.T. participated in the conception and design of the study, writing and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, and final approval of the manuscript submitted. A.R.T. is the guarantor of the paper, taking responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, from inception to published article.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Lee J, Kirschner J, Pawa S, Wiener DE, Newman DH, Shah K. Computed tomography use in the adult emergency department of an academic urban hospital from 2001 to 2007. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56:591–596. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith-Bindman R, Miglioretti DL, Johnson E, Lee C, Feigelson HS, Flynn M, Greenlee RT, Kruger RL, Hornbrook MC, Roblin D, et al. Use of diagnostic imaging studies and associated radiation exposure for patients enrolled in large integrated health care systems, 1996-2010. JAMA. 2012;307:2400–2409. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haimovici JB, Trotman-Dickenson B, Halpern EF, Dec GW, Ginns LC, Shepard JA, McLoud TC Massachusetts General Hospital Lung Transplantation Program. Relationship between pulmonary artery diameter at computed tomography and pulmonary artery pressures at right-sided heart catheterization. Acad Radiol. 1997;4:327–334. doi: 10.1016/s1076-6332(97)80111-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuriyama K, Gamsu G, Stern RG, Cann CE, Herfkens RJ, Brundage BH. CT-determined pulmonary artery diameters in predicting pulmonary hypertension. Invest Radiol. 1984;19:16–22. doi: 10.1097/00004424-198401000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lange TJ, Dornia C, Stiefel J, Stroszczynski C, Arzt M, Pfeifer M, Hamer OW. Increased pulmonary artery diameter on chest computed tomography can predict borderline pulmonary hypertension. Pulm Circ. 2013;3:363–368. doi: 10.4103/2045-8932.113175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCall RK, Ravenel JG, Nietert PJ, Granath A, Silver RM. Relationship of main pulmonary artery diameter to pulmonary arterial pressure in scleroderma patients with and without interstitial fibrosis. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2014;38:163–168. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0b013e3182aa7fc5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tan RT, Kuzo R, Goodman LR, Siegel R, Haasler GB, Presberg KW Medical College of Wisconsin Lung Transplant Group. Utility of CT scan evaluation for predicting pulmonary hypertension in patients with parenchymal lung disease. Chest. 1998;113:1250–1256. doi: 10.1378/chest.113.5.1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pérez-Enguix D, Morales P, Tomás JM, Vera F, Lloret RM. Computed tomographic screening of pulmonary arterial hypertension in candidates for lung transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2007;39:2405–2408. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2007.07.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mahammedi A, Oshmyansky A, Hassoun PM, Thiemann DR, Siegelman SS. Pulmonary artery measurements in pulmonary hypertension: the role of computed tomography. J Thorac Imaging. 2013;28:96–103. doi: 10.1097/RTI.0b013e318271c2eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Devaraj A, Wells AU, Meister MG, Corte TJ, Wort SJ, Hansell DM. Detection of pulmonary hypertension with multidetector CT and echocardiography alone and in combination. Radiology. 2010;254:609–616. doi: 10.1148/radiol.09090548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grubstein A, Benjaminov O, Dayan DB, Shitrit D, Cohen M, Kramer MR. Computed tomography angiography in pulmonary hypertension. Isr Med Assoc J. 2008;10:117–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bouchard A, Higgins CB, Byrd BF, III, Amparo EG, Osaki L, Axelrod R. Magnetic resonance imaging in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Cardiol. 1985;56:938–942. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(85)90408-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frank H, Globits S, Glogar D, Neuhold A, Kneussl M, Mlczoch J. Detection and quantification of pulmonary artery hypertension with MR imaging: results in 23 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1993;161:27–31. doi: 10.2214/ajr.161.1.8517315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murray TI, Boxt LM, Katz J, Reagan K, Barst RJ. Estimation of pulmonary artery pressure in patients with primary pulmonary hypertension by quantitative analysis of magnetic resonance images. J Thorac Imaging. 1994;9:198–204. doi: 10.1097/00005382-199422000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galiè N, Simonneau G. The fifth world symposium on pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:D1–D3. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rich S, Dantzker DR, Ayres SM, Bergofsky EH, Brundage BH, Detre KM, Fishman AP, Goldring RM, Groves BM, Koerner SK, et al. Primary pulmonary hypertension: a national prospective study. Ann Intern Med. 1987;107:216–223. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-107-2-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.George MG, Schieb LJ, Ayala C, Talwalkar A, Levant S. Pulmonary hypertension surveillance: United States, 2001 to 2010. Chest. 2014;146:476–495. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-0527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Badesch DB, Raskob GE, Elliott CG, Krichman AM, Farber HW, Frost AE, Barst RJ, Benza RL, Liou TG, Turner M, et al. Pulmonary arterial hypertension: baseline characteristics from the REVEAL Registry. Chest. 2010;137:376–387. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoeper MM, Bogaard HJ, Condliffe R, Frantz R, Khanna D, Kurzyna M, Langleben D, Manes A, Satoh T, Torres F, et al. Definitions and diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:D42–D50. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown LM, Chen H, Halpern S, Taichman D, McGoon MD, Farber HW, Frost AE, Liou TG, Turner M, Feldkircher K, et al. Delay in recognition of pulmonary arterial hypertension: factors identified from the REVEAL Registry. Chest. 2011;140:19–26. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kawut SM, Silvestry FE, Ferrari VA, DeNofrio D, Axel L, Loh E, Palevsky HI.Extrinsic compression of the left main coronary artery by the pulmonary artery in patients with long-standing pulmonary hypertension Am J Cardiol 199983984–986., A10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nguyen ET, Silva CI, Seely JM, Chong S, Lee KS, Müller NL. Pulmonary artery aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms in adults: findings at CT and radiography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188:W126-34. doi: 10.2214/AJR.05.1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Truong QA, Massaro JM, Rogers IS, Mahabadi AA, Kriegel MF, Fox CS, O’Donnell CJ, Hoffmann U. Reference values for normal pulmonary artery dimensions by noncontrast cardiac computed tomography: the Framingham Heart Study. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;5:147–154. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.111.968610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edwards PD, Bull RK, Coulden R. CT measurement of main pulmonary artery diameter. Br J Radiol. 1998;71:1018–1020. doi: 10.1259/bjr.71.850.10211060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karazincir S, Balci A, Seyfeli E, Akoğlu S, Babayiğit C, Akgül F, Yalçin F, Eğilmez E. CT assessment of main pulmonary artery diameter. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2008;14:72–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burger IA, Husmann L, Herzog BA, Buechel RR, Pazhenkottil AP, Ghadri JR, Nkoulou RN, Jenni R, Russi EW, Kaufmann PA. Main pulmonary artery diameter from attenuation correction CT scans in cardiac SPECT accurately predicts pulmonary hypertension. J Nucl Cardiol. 2011;18:634–641. doi: 10.1007/s12350-011-9413-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ng CS, Wells AU, Padley SP. A CT sign of chronic pulmonary arterial hypertension: the ratio of main pulmonary artery to aortic diameter. J Thorac Imaging. 1999;14:270–278. doi: 10.1097/00005382-199910000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stenmark KR, Bouchey D, Nemenoff R, Dempsey EC, Das M. Hypoxia-induced pulmonary vascular remodeling: contribution of the adventitial fibroblasts. Physiol Res. 2000;49:503–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shankarappa RK, Moorthy N, Chandrasekaran D, Nanjappa MC. Giant pulmonary artery aneurysm secondary to primary pulmonary hypertension. Tex Heart Inst. 2010;37:244–245. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perloff JK. Patent ductus arteriosus. In: Perloff JK, editor. The clinical recognition of congenital heart disease. 2nd ed. 1922. pp. 524–560. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bartter T, Irwin RS, Nash G. Aneurysms of the pulmonary arteries. Chest. 1988;94:1065–1075. doi: 10.1378/chest.94.5.1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fenster BE, Schroeder JD, Hertzberg JR, Chung JH. 4-Dimensional cardiac magnetic resonance in a patient with bicuspid pulmonic valve: characterization of post-stenotic flow. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:e49. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.09.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kutty S, Kaul S, Danford CJ, Danford DA. Main pulmonary artery dilation in association with congenital bicuspid aortic valve in the absence of pulmonary valve abnormality. Heart. 2010;96:1756–1761. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2010.199109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.International Study Group for Behçet’s Disease. Criteria for diagnosis of Behçet’s disease. Lancet. 1990;335:1078–1080. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Erkan F, Gül A, Tasali E. Pulmonary manifestations of Behçet’s disease. Thorax. 2001;56:572–578. doi: 10.1136/thorax.56.7.572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Uzun O, Akpolat T, Erkan L. Pulmonary vasculitis in Behçet disease: a cumulative analysis. Chest. 2005;127:2243–2253. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.6.2243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kuppler KM, Kirse DJ, Thompson JT, Haldeman-Englert CR. Loeys-Dietz syndrome presenting as respiratory distress due to pulmonary artery dilation. Am J Med Genet A. 2012;158A:1212–1215. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.35274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nollen GJ, van Schijndel KE, Timmermans J, Groenink M, Barentsz JO, van der Wall EE, Stoker J, Mulder BJ. Pulmonary artery root dilatation in Marfan syndrome: quantitative assessment of an unknown criterion. Heart. 2002;87:470–471. doi: 10.1136/heart.87.5.470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Restrepo CS, Carswell AP. Aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms of the pulmonary vasculature. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2012;33:552–566. doi: 10.1053/j.sult.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ha HI, Seo JB, Lee SH, Kang JW, Goo HW, Lim TH, Shin MJ. Imaging of Marfan syndrome: multisystemic manifestations. Radiographics. 2007;27:989–1004. doi: 10.1148/rg.274065171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ercan S, Dogan A, Altunbas G, Davutoglu V. Giant pulmonary artery aneurysm: 12 years of follow-up. case report and review of the literature. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;62:450–452. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1331578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Senbaklavaci O, Kaneko Y, Bartunek A, Brunner C, Kurkciyan E, Wunderbaldinger P, Klepetko W, Wolner E, Mohl W. Rupture and dissection in pulmonary artery aneurysms: incidence, cause, and treatment—review and case report. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001;121:1006–1008. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2001.112634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boerrigter B, Mauritz GJ, Marcus JT, Helderman F, Postmus PE, Westerhof N, Vonk-Noordegraaf A. Progressive dilatation of the main pulmonary artery is a characteristic of pulmonary arterial hypertension and is not related to changes in pressure. Chest. 2010;138:1395–1401. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heinrich M, Uder M, Tscholl D, Grgic A, Kramann B, Schäfers HJ. CT scan findings in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: predictors of hemodynamic improvement after pulmonary thromboendarterectomy. Chest. 2005;127:1606–1613. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.5.1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Walsh SL, Wells AU, Sverzellati N, Keir GJ, Calandriello L, Antoniou KM, Copley SJ, Devaraj A, Maher TM, Renzoni E, et al. An integrated clinicoradiological staging system for pulmonary sarcoidosis: a case-cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2:123–130. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(13)70276-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Żyłkowska J, Kurzyna M, Florczyk M, Burakowska B, Grzegorczyk F, Burakowski J, Wieteska M, Oniszh K, Biederman A, Wawrzyńska L, et al. Pulmonary artery dilatation correlates with the risk of unexpected death in chronic arterial or thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Chest. 2012;142:1406–1416. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Botney MD. Role of hemodynamics in pulmonary vascular remodeling: implications for primary pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:361–364. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.2.9805075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang Z, Chesler NC. Role of collagen content and cross-linking in large pulmonary arterial stiffening after chronic hypoxia. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2012;11:279–289. doi: 10.1007/s10237-011-0309-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ooi CY, Wang Z, Tabima DM, Eickhoff JC, Chesler NC. The role of collagen in extralobar pulmonary artery stiffening in response to hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;299:H1823–H1831. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00493.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang Z, Lakes RS, Eickhoff JC, Chesler NC. Effects of collagen deposition on passive and active mechanical properties of large pulmonary arteries in hypoxic pulmonary hypertension. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2013;12:1115–1125. doi: 10.1007/s10237-012-0467-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kobs RW, Chesler NC. The mechanobiology of pulmonary vascular remodeling in the congenital absence of eNOS. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2006;5:217–225. doi: 10.1007/s10237-006-0018-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lammers SR, Kao PH, Qi HJ, Hunter K, Lanning C, Albietz J, Hofmeister S, Mecham R, Stenmark KR, Shandas R. Changes in the structure-function relationship of elastin and its impact on the proximal pulmonary arterial mechanics of hypertensive calves. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H1451–H1459. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00127.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Frid MG, Li M, Gnanasekharan M, Burke DL, Fragoso M, Strassheim D, Sylman JL, Stenmark KR. Sustained hypoxia leads to the emergence of cells with enhanced growth, migratory, and promitogenic potentials within the distal pulmonary artery wall. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;297:L1059–L1072. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.90611.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stenmark KR, Davie N, Frid M, Gerasimovskaya E, Das M. Role of the adventitia in pulmonary vascular remodeling. Physiology (Bethesda) 2006;21:134–145. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00053.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stenmark KR, Gerasimovskaya E, Nemenoff RA, Das M. Hypoxic activation of adventitial fibroblasts: role in vascular remodeling. Chest. 2002;122:326S–334S. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.6_suppl.326s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moore NR, Scott JP, Flower CD, Higenbottam TW. The relationship between pulmonary artery pressure and pulmonary artery diameter in pulmonary hypertension. Clin Radiol. 1988;39:486–489. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(88)80205-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Teichmann V, Jezek V, Herles F. Relevance of width of right descending branch of pulmonary artery as a radiological sign of pulmonary hypertension. Thorax. 1970;25:91–96. doi: 10.1136/thx.25.1.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Devaraj A, Wells AU, Meister MG, Corte TJ, Hansell DM. The effect of diffuse pulmonary fibrosis on the reliability of CT signs of pulmonary hypertension. Radiology. 2008;249:1042–1049. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2492080269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zisman DA, Karlamangla AS, Ross DJ, Keane MP, Belperio JA, Saggar R, Lynch JP, III, Ardehali A, Goldin J. High-resolution chest CT findings do not predict the presence of pulmonary hypertension in advanced idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest. 2007;132:773–779. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-0116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fedak PW, de Sa MP, Verma S, Nili N, Kazemian P, Butany J, Strauss BH, Weisel RD, David TE. Vascular matrix remodeling in patients with bicuspid aortic valve malformations: implications for aortic dilatation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;126:797–806. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(03)00398-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yu SB, Zhao QY, Huang H, Chen DE, Cui HY, Qin M, Huang CX. Prognosis investigation in patients with chronic heart failure and pericardial effusion. Chin Med J (Engl) 2012;125:882–887. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nadrous HF, Pellikka PA, Krowka MJ, Swanson KL, Chaowalit N, Decker PA, Ryu JH. Pulmonary hypertension in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest. 2005;128:2393–2399. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.4.2393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Alhamad EH, Al-Boukai AA, Al-Kassimi FA, Alfaleh HF, Alshamiri MQ, Alzeer AH, Al-Otair HA, Ibrahim GF, Shaik SA. Prediction of pulmonary hypertension in patients with or without interstitial lung disease: reliability of CT findings. Radiology. 2011;260:875–883. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11103532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wells JM, Washko GR, Han MK, Abbas N, Nath H, Mamary AJ, Regan E, Bailey WC, Martinez FJ, Westfall E, et al. COPDGene Investigators; ECLIPSE Study Investigators. Pulmonary arterial enlargement and acute exacerbations of COPD. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:913–921. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1203830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Alzeer AH, Al-Mobeirek AF, Al-Otair HA, Elzamzamy UA, Joherjy IA, Shaffi AS. Right and left ventricular function and pulmonary artery pressure in patients with bronchiectasis. Chest. 2008;133:468–473. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Devaraj A, Wells AU, Meister MG, Loebinger MR, Wilson R, Hansell DM. Pulmonary hypertension in patients with bronchiectasis: prognostic significance of CT signs. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196:1300–1304. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.5221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Minai OA, Ricaurte B, Kaw R, Hammel J, Mansour M, McCarthy K, Golish JA, Stoller JK. Frequency and impact of pulmonary hypertension in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104:1300–1306. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kawano Y, Tamura A, Watanabe T, Kadota J. Severe obstructive sleep apnoea is independently associated with pulmonary artery dilatation. Respirology. 2013;18:1148–1151. doi: 10.1111/resp.12123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Liu M, Ma Z, Guo X, Zhang H, Yang Y, Wang C. Computed tomographic pulmonary angiography in the assessment of severity of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension and right ventricular dysfunction. Eur J Radiol. 2011;80:e462–e469. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2010.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schmidt HC, Kauczor HU, Schild HH, Renner C, Kirchhoff E, Lang P, Iversen S, Thelen M. Pulmonary hypertension in patients with chronic pulmonary thromboembolism: chest radiograph and CT evaluation before and after surgery. Eur Radiol. 1996;6:817–825. doi: 10.1007/BF00240678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schölzel BE, Post MC, Dymarkowski S, Wuyts W, Meyns B, Budts W, Morshuis W, Snijder RJ, Delcroix M. Prediction of outcome after PEA in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension using indexed pulmonary artery diameter. Eur Respir J. 2014;43:909–912. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00174113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shorr AF, Davies DB, Nathan SD. Predicting mortality in patients with sarcoidosis awaiting lung transplantation. Chest. 2003;124:922–928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Choi YJ, Kim U, Lee JS, Park WJ, Lee SH, Park JS, Shin DG, Kim YJ. A case of extrinsic compression of the left main coronary artery secondary to pulmonary artery dilatation. J Korean Med Sci. 2013;28:1543–1548. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2013.28.10.1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mesquita SM, Castro CR, Ikari NM, Oliveira SA, Lopes AA. Likelihood of left main coronary artery compression based on pulmonary trunk diameter in patients with pulmonary hypertension. Am J Med. 2004;116:369–374. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sahay S, Tonelli AR. Ventricular fibrillation caused by extrinsic compression of the left main coronary artery. Heart. 2013;99:895–896. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2012-303408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kothari SS, Chatterjee SS, Sharma S, Rajani M, Wasir HS. Left main coronary artery compression by dilated main pulmonary artery in atrial septal defect. Indian Heart J. 1994;46:165–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mitsudo K, Fujino T, Matsunaga K, Doi O, Nishihara Y, Awa J, Goto T, Hase T, Sakamoto T, Toda M, et al. [Coronary arteriographic findings in the patients with atrial septal defect and pulmonary hypertension (ASD + PH)—compression of left main coronary artery by pulmonary trunk] Kokyu To Junkan. 1989;37:649–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.McLaughlin VV, Archer SL, Badesch DB, Barst RJ, Farber HW, Lindner JR, Mathier MA, McGoon MD, Park MH, Rosenson RS, et al. American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Expert Consensus Documents; American Heart Association; American College of Chest Physicians; American Thoracic Society, Inc; Pulmonary Hypertension Association. ACCF/AHA 2009 expert consensus document on pulmonary hypertension a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Expert Consensus Documents and the American Heart Association developed in collaboration with the American College of Chest Physicians; American Thoracic Society, Inc.; and the Pulmonary Hypertension Association. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:1573–1619. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wong LF, Akram AR, McGurk S, Van Beek EJ, Reid JH, Murchison JT. Thrombus load and acute right ventricular failure in pulmonary embolism: correlation and demonstration of a “tipping point” on CT pulmonary angiography. Br J Radiol. 2012;85:1471–1476. doi: 10.1259/bjr/22397455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gupta V, Tonelli AR, Krasuski RA. Congenital heart disease and pulmonary hypertension. Heart Fail Clin. 2012;8:427–445. doi: 10.1016/j.hfc.2012.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Xu XQ, Jing ZC. High-altitude pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir Rev. 2009;18:13–17. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00011104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Butrous G. Saudi guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: schistosomiasis and pulmonary arterial hypertension. Ann Thorac Med. 2014;9:S38–S41. doi: 10.4103/1817-1737.134019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Morjaria S, Grinnan D, Voelkel N. Massive dilatation of the pulmonary artery in association with pulmonic stenosis and pulmonary hypertension. Pulm Circ. 2012;2:256–257. doi: 10.4103/2045-8932.97640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mao JR, Bristow J. The Ehlers-Danlos syndrome: on beyond collagens. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:1063–1069. doi: 10.1172/JCI12881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yuan SM, Jing H. Cystic medial necrosis: pathological findings and clinical implications. Rev Bras Cir Cardiovasc. 2011;26:107–115. doi: 10.1590/s0102-76382011000100019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Orman G, Guvenc TS, Balci B, Duymus M, Sevingil T. Idiopathıc pulmonary artery aneurysm. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;95:e33–e34. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Seguchi M, Wada H, Sakakura K, Kubo N, Ikeda N, Sugawara Y, Yamaguchi A, Ako J, Momomura S. Idiopathic pulmonary artery aneurysm. Circulation. 2011;124:e369–e370. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.029033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Frazier AA, Galvin JR, Franks TJ, Rosado-De-Christenson ML.From the archives of the AFIP: pulmonary vasculature: hypertension and infarction Radiographics 200020491–524.; quiz 530–491, 532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sanal S, Aronow WS, Ravipati G, Maguire GP, Belkin RN, Lehrman SG. Prediction of moderate or severe pulmonary hypertension by main pulmonary artery diameter and main pulmonary artery diameter/ascending aorta diameter in pulmonary embolism. Cardiol Rev. 2006;14:213–214. doi: 10.1097/01.crd.0000181619.87084.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]