Abstract

Patients affected by glycogenosis type II frequently present sleepdisordered breathing. The presence of symptoms suggestive of sleep breathing disorders was investigated, by a questionnaire, in 10 patients, affected by adult or juvenile forms of glycogenosis type II. Diurnal respiratory function, diaphragm weakness and nocturnal respiratory pattern were evaluated at the enrolment. In patients presenting sleep disordered breathing, the same parameters were re-evaluated after treatment with assisted non invasive ventilation. Out of 10 patients, 5 presented symptoms suggestive of sleep-disordered breathing at the baseline, 2 a pattern of sleep apnea syndrome and 3 nocturnal hypoventilation. All patients presented diaphragmatic weakness. No correlation was found between forced vital capacity values (FVC) in sit position and nocturnal respiratory disorders. Five patients with respiratory disorders were treated with non invasive ventilation. All patients – after one month of treatment - showed an improvement in symptoms with reduced diurnal hypersomnia (ESS < 10), absence of morning headaches and nocturnal awakenings, and reduced nicturia regardless the modality of ventilation. We recommend that all patients with glycogenosis type II, once diagnosed, are carefully monitored for the development of respiratory involvement, even in the absence of reduced FVC values and in the early stages of the disease, to receive appropriate therapy.

Key words: glycogenosis, apnoea, hypopnea, hypoventilation, non invasive ventilation

Background

Patients with glycogenosis type II, also known as Pompe disease, are susceptible to the development of sleep disordered breathing (SDB). Sleep, with its reduction in ventilatory responses (1, 2), represents a major stress to weakened respiratory muscles and an opportune time to asses the ventilatory reserve. Sleep disordered breathing is found in 40-70% of patients with neuromuscular diseases (3, 4), but relates poorly to daytime functional variables (5). Recognition of nocturnal hypoventilation is of particular importance because it contributes to the development of respiratory failure (6). Unfortunately, a simple relationship between awake measurements of respiratory function and nocturnal breathing events has not been found (7-10). Symptoms suggestive of SDB are often underestimated, particularly in patients with neuromuscular diseases (4, 11). The presence of symptoms such as morning headaches and daytime hypersomnia may interfere heavily on the quality of life of these patients. The treatment of respiratory disorders can therefore have a strong impact on improving their quality of life (12-14).

Aims of the study were: 1) to evaluate respiratory function, nocturnal respiratory pattern and presence of symptoms suggestive of sleep-disordered breathing in a group of 10 patients, affected by Glycogenosis type II; 2) to investigate the relationship between diurnal respiratory function, diaphragmatic dysfunction and nocturnal breathing patterns; 3) to assess the improvement in symptoms after treatment with non invasive ventilation (NIV).

Patients and methods

Ten patients affected by adult or juvenile form of glycogenosis type II (Table 1) aged 41,2 ± 13,3 were progressively enrolled. All patients – at the enrolment – filled in a questionnaire on the presence of the following symptoms: a) excessive daytime sleepiness; b) choking or gasping during sleep; c) recurrent awakenings from sleep; d) unrefreshing sleep; e) daytime fatigue; f) morning headaches; g) nicturia and h) impaired concentration.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients.

| Patient | Age | FVC% | FEV1% | DW | SYM | CO2>45 | AHI | T90 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 21 | 74 | 75 | N | N | N | 3 | 6 |

| 2 | 48 | 73 | 68 | N | Y | N | 14 | 8 |

| 3 | 28 | 67 | 70 | N | N | N | 4 | 1 |

| 4 | 50 | 62 | 61 | Y | Y | N | 6 | 32 |

| 5 | 49 | 61 | 61 | Y | Y | Y | 5 | 44 |

| 6 | 27 | 63 | 62 | N | Y | N | 16 | 9 |

| 7 | 31 | 66 | 66 | N | N | N | 4 | 0 |

| 8 | 57 | 58 | 58 | N | N | N | 2 | 6 |

| 9 | 43 | 49 | 49 | Y | Y | Y | 5 | 30 |

| 10 | 58 | 57 | 57 | N | N | N | 2 | 6 |

Legend Y: yes; N: no; FVC: forced vital capacity; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in one second; DW: diaphragm weakness; SYM: symptoms; AHI: Apnea/Hypopnea per hour; T90: % time with arterial oxygen saturation less than 90%

All patients underwent a respiratory investigation including pneumological examination, measure of ventilator capacity, arterial blood gas determination and polysomnography. Ventilatory capacity was investigated by vital capacity (VC), forced vital capacity (FVC) and forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), measured by a hand-held spirometer (SpirolabIII, MIR). Measurements were obtained both in sitting and supine positions to evaluate diaphragm weakness. The best of tree consistent efforts (< 5% variability) was used. The reduction in lung function was classified according to ATS/ERS criteria. The defect was considered mild for values of FEV1 > 70% of the expected, moderate for values between 60 to 69%, moderately- severe for values between 50 to 59%, severe for values between 35% to 49%, and very severe for values < 35% of the expected, according to age, height and weight. Arterial blood gas tension was determined in the arterial blood of the earlobe, by automated blood gas analyzer (OMNI 6 MODULAR SYSTEM AVL).

Overnight polysomnography was performed in all patients, without oxygen supplementation. Sleep stages, electroencephalogram, electro-oculogram, submental electromyogram, electrocardiogram, oro-nasal flow and respiratory movement sensors, as far as oxyemoglobin saturation were recorded using a computerized work station (SOMNO lab, Weinmann). Sleep stages and respiratory parameters were scored manually. Analyses were performed using the American Academy Sleep Medicine scores. The sleep disorders breathing was sub-classified into two distinct syndromes, namely, 1) obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome (OSAHS), and 2) sleep hypoventilation syndrome (SHVS). OSAHS was diagnosed when sleep monitoring demonstrated 5 or more apneas/hypopneas episodes/hour during sleep (AHI > 5). SHVS was diagnosed in presence of PaCO2 values > 10 mmHg on waking in the morning, compared with awake supine values, and/or in presence of sustained hypoxemia with arterial oxygen saturation [SaO2] < 90% for more than 30% of the registration period, during sleep (T90 > 30%), not related to apnea or hypopnea episodes. Patients showing SDB were addressed to ventilatory assistance and treated by continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP autoset spirit, ResMed) or non invasive ventilation (NIV with VSIII ResMed) in pressure support, with synchronised tidal volume. Parameters were set individually. Nasal masks were preferentially used, unless special needs of the patient. In this case, a facial mask was used. These patients were re-evaluated by the same parameters, 30 days after the treatment. No patient was in enzyme replacement therapy (ERT).

Results

Diurnal respiratory function

All patients presented restrictive ventilatory defect. Two had a mild reduction of respiratory capacity; 4 patients presented a moderate reduction; 3 a moderate-severe, and 1 had a severe reduction. Diaphragm weakness (DW, postural drop of VC ≥ 20 %) was present in 3/7 patients.

Arterial blood gas analysis

Two patients presented diurnal hypercapnia > 5,9 kPa (45 mmHg).

Sleep disordered breathing

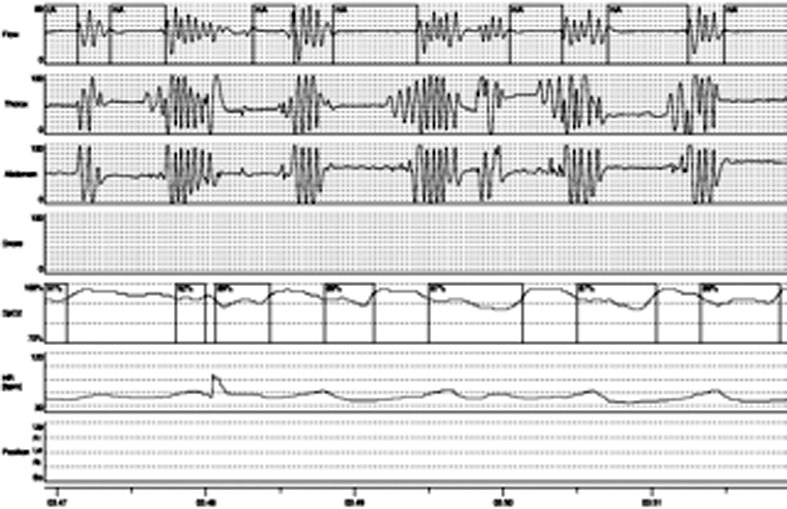

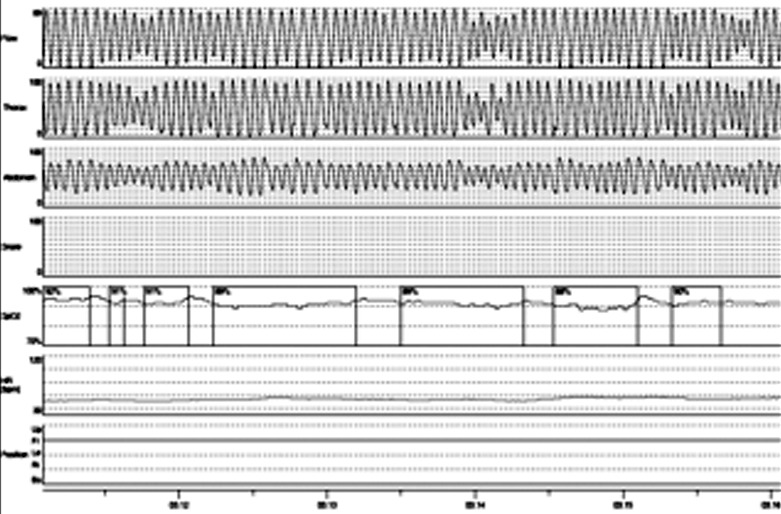

Five patients presented hypersomnia (ESS > 10), morning headaches, sleep disturbance, nicturia and impaired concentration. Of these, three patients complained awakenings and choking or gasping during sleep. SDB was found in five patients, three with diaphragm weakness, two without. Two subjects had findings consistent with sleep apnea syndrome (OSAHS: AHI > 5; T90 < 20%) (Fig. 1); in three patients with diaphragm weakness, REM sleep hypopneas with REM sleep hypoventilation and continuous sleep stage-indipendent hypoventilation (SHVS: AHI ≤ 5; T90 > 30%) were found (Fig. 2). The 5 patients presenting sleep disordered breathing, started therapy with non invasive positive pressure ventilation: 2 patients were well adapted with CPAP while 3 needed pressure support ventilation with target volume. After one month of treatment, all treated patients reported an improvement in symptoms with reduced diurnal hypersomnia (ESS < 10), absence of morning headache and nocturnal awakenings, reduced nicturia (Table 2), regardless of the modality of ventilation.

Figure 1.

Apnea.

Figure 2.

Desaturazione.

Table 2.

Mechanical ventilation in patients treated.

| Patient | Mode of MV | Mask | Time of ventilation per day | Difference in ESS score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PSV/VT | Full Face | 8 | -8 |

| 2 | PSV/VT | Nasal | 8 | -7 |

| 3 | PSV/VT | Nasal | 6 | -5 |

| 4 | CPAP | Nasal | 6 | -8 |

| 5 | CPAP | Nasal | 5 | -7 |

PSV/VT:pressure-support ventilation with target volume; CPAP: continuous positive airway pressure; ESS: Epworth Sleepiness Scale.

Discussion

The presence of sleep disordered breathing is too often overlooked in patients with neuromuscular diseases until the development of awake respiratory failure. Part of the problems lies in the difficulty of identifying symptoms associated with sleep breathing disorders in these patients., as they may maintain a good daytime function with minimal symptoms, despite significant apneas and severe nocturnal oxygen desaturation (15).

In our series, 5 patients (50%), had symptoms suggestive of sleep disordered breathing confirmed by an altered nocturnal breathing pattern. Three patients had diaphragmatic weakness and presented nocturnal hypoventilation with a pattern of latent chronic respiratory insufficiency. Two patients had a nocturnal breathing pattern type apnea/hypopnea. The role of diaphragm in these disease is fundamental. If the diaphragmatic strength is preserved but the upper airway or intercostal muscles are weak, then obstructive events are likely to predominate. On the other hand, when patients have severe diaphragmatic dysfunction, suppression of intercostal and accessory muscles during sleep will produce hypoventilation and abnormalities in gas exchanges (14). The presence of sleep hypoventilation is particularly important to be diagnosed, because it usually precedes the development of diurnal respiratory failure (15). Furthermore, in patients with neuromuscular diseases OSAHS may be responsible for significant daytime disability such as excessive daytime sleepiness and cognitive dysfunction. To recognize an altered nocturnal breathing is of particular importance because it represents an early sign of respiratory dysfunction. Many factors such as obesity, scoliosis, ability to arouse from sleep, and other compensatory mechanisms can contribute to influence the severity of SDB and gas exchange defects. In such cases an early investigation of presence of SDB and its monitoring after the beginning of therapy, is recommended. Failure to recognize and treat SBD may contribute to unnecessary disability or even to premature death in these patients (16, 17). Treatment with NIV, accepted by all patients with good compliance, is able to reduce symptoms reported by patients (morning headaches, nicturia) and also improve the quality of life of patients, while reducing the frequency of hospitalizations and increasing their life expectancy (18-22), even in patients not receiving ERT. Therefore we recommend that all patients with Glycogenosis type II or Pompe Diseases, once diagnosed, are carefully monitored for the development of respiratory involvement, even in the absence of reduced FVC values and in the early stages of the disease, to receive appropriate treatment.

References

- 1.Beek NA1, Capelle CI, Etten KI, et al. Rate of progression and predictive factors for pulmonary outcome in children and adults with Pompe disease. Mol Genet Metab. 2011;104:129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2011.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lopes JM, Tabachnik E, Muller NL, et al. Total airway resistance and respiratory muscle activity during sleep. J Appl Physiol. 1983;54:773–777. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1983.54.3.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lunteren E, Kaminski H. Disorders of sleep and breathing during sleep in neuromuscular disease. Sleep Breathing. 1999;3:23–30. doi: 10.1007/s11325-999-0023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Labanowski M, Schmidt-Nowara W, Guilleminault C. Sleep and neuromuscular disease: frequency of sleep disordered breathing in a neuromuscular disease clinic population. Neurology. 1996;47:1173–1180. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.5.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khan Y, Heckmatt JZ. Obstructive sleep apneas in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Thorax. 1994;49:157–161. doi: 10.1136/thx.49.2.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simonds AK, Muntoni F, Heather S, et al. Impact of nasal ventilation on survival in hypercapnic Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Thorax. 1998;53:949–952. doi: 10.1136/thx.53.11.949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hukins CA, Hillman DR. Daytime predictors of sleep hypoventilation in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:166–170. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.1.9901057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jackson CE, Rosenfeld J, Moore DH, et al. A preliminary evaluation of a prospective study of pulmonary function studies and symptoms of hypoventilation in ALS/MND patients. J Neurol Sci. 2001;191:75–78. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(01)00617-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liam CK, Lim KH, Wong CM, et al. Awake respiratory function in patients with the obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome. Med J Malaysia. 2001;56:10–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mellies U, Ragette R, Schwake C, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing and respiratory failure in acid maltase deficiency. Neurology. 2001;57:1290–1295. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.7.1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guilleminault C, Philip P, Robinson A. Sleep and neuromuscolar disease: bilevel positive airway pressure by nasal mask as a treatment for sleep disordered breathing in patient with neuromuscular disease. J Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1998;65:225–232. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.65.2.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lyall RA, Donaldson N, Fleming T, et al. A prospective study of quality of life in ALS patient treated with noninvasive ventilation. Neurology. 2001;57:153–156. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.1.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aboussouan LS, Khan SU, Banerjee M, et al. Objective measures of the efficacy of noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Muscle Nerve. 2001;24:403–409. doi: 10.1002/1097-4598(200103)24:3<403::aid-mus1013>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Piper A. Sleep abnormalities associated with neuromuscular disease: Pathophysiology and evaluation. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;23:212–219. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-33029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benditt JO, Boitano LJ. Pulmonary issues in patients with chronic neuromuscular disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:1046–1055. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201210-1804CI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hutchinson D, Whyte K. Neuromuscular disease and respiratory failure. Pract Neurol. 2008;8:229–237. doi: 10.1136/pn.2008.152611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Passamano L, Taglia A, Palladino A, et al. Improvement of survival in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: retrospective analysis of 835 patients. Acta Myol. 2012;31:121–125. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Radunovic A, Annane D, Rafiq MK, et al. Mechanical ventilation for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/motor neuron disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;3:CD004427–CD004427. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004427.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vianello A, Bevilacqua M, Salvador V, et al. Long-term nasal intermittent positive pressure ventilation in advanced Duchenne's muscular dystrophy. Chest. 1994;105:445–448. doi: 10.1378/chest.105.2.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bach JR. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: prolongation of life by noninvasive respiratory AIDS. Chest. 2002;122:92–98. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.1.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rideau Y, Delaubier A, Guillou C, et al. Treatment of respiratory insufficiency in Duchenne's muscular dystrophy: nasal ventilation in the initial stages. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 1995;50:235–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rideau Y, Politano L. Research against incurability. Treatment of lethal neuromuscular diseases focused on Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Acta Myol. 2004;23:163–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]