INTRODUCTION

Stillbirth defies the modern expectation of a healthy outcome for pregnancy. It prompts many complex emotional responses which have numerous distinctive characteristics. The grief reaction following a stillbirth has been demonstrated to be comparable to other types of bereavement (Chan, Lou, Arthur, Cao, Wu, Li & Lui, 2008:509) with potential to cause serious short-term and long-tenn psychological problems. An event that should have been a joyous birth ends in a tragic death, forcing the mother to deal with the emotions surrounding birth and death simultaneously (Human, 2013: I). Stillbirth is a major problem in South Africa. During a 2-year-period ending on 31st December 2011, 32,178 stillbirths were tracked by the Perinatal Problem Identification Program at 588 sites in South Africa.

It is now recognized that perinatal loss presents a situation where the early activation of the grief process is exacerbated by the circumstances of the loss (Kirk, 1984:46). Reasons cited as contributing to the complexity of this process are: (1) Lack of memories surrounding the baby, thus creating an absence of the “object” to mourn (De Montigny, Beaudet & Dumas, 1999:151-156); (2) Sense of biological failure, especially felt by the mother; (3) Minimization by others as well as lack of validation from others; and (4) Uncertainty regarding further pregnancies or parental future hopes (Hutti, 2005:630). Not only the parents of the demised baby suffer consequences but the loss also has an impact on family and friends as well as on the family's socio-economic environment (Kirkley-Best & Kellner, 1982:420).

As in any loss, a period of grieving is essential for adjustment following a stillbirth. (Brier, 2008:451; Hughes & Riches, 2003:1; Capitulo, 2005:390; Hutti, 2005:630). This grieving can be a very lonely process owing to a lack of understanding of the unique and complex character of the loss. Grief following miscarriage, stillbirth or neonatal death is particularly susceptible to being disenfranchised, as only parents have “known” the baby, felt it move, or observed it by ultrasound. Modiba and Nolte (2007:4) reported that mothers who suffered perinatal loss expressed the wish that people should acknowledge their losses, be considerate and sensitive, be sympathetic listeners and offer emotional support. This contrastswith typical social norms, where the loss is considered of lesser gravity. Grieving is not a solitary enterprise, therefore it is important to see the family as a holistic entity and not as separate entities.

Brownlee and Oikonen (2004:526) recommended further research to address the social context of perinatal bereavement and the impact of factors compounding grief, such as financial resources, culture and social identity. Neglected in the literature, these issues may influence people's style of grieving and the meaning they attribute to their loss. Brownlee and Oikonen (2004:526) further stated that social workers, by virtue of their knowledge of the social environment in which a person lives and its impact on social problems and emotional well-being, are in a good position to address these issues and make a substantial contribution to the theoretical and practical literature on perinatal bereavement as well as rendering crisis intervention to the family. According to Kellner, Best, Chesborough, Donnelly and Green (1981:29-35) literature does not often facilitate applied approaches on how to support families following a stillbirth. Therefore this paper aims to clarify essential elements of crisis intervention as a preferred approach. The crisis-intervention model is usually used to address the needs and concerns of a client suffering an acute, psychological crisis. Crisis intervention can be defined as follows: “It is a process for actively influencing psychosocial functioning during a period of disequilibrium in order to alleviate the immediate impact of disruptive stressful events and to help mobilize the psychological capabilities and social resources of persons directly affected by the crisis” (Sheafor, Horejsi & Horejsi, 1994:68-69). Intervention efforts have two principal aims: (1) To cushion the stressful event by immediate or emergency emotional and environmental first aid, and (2) To strengthen the person in his or her coping through immediate therapeutic clarification and guidance during the crisis period (Sheafor et al., 1994:68-69).

Cacciatore (2009:93) agrees with Brownlee and Oikonen (2004:526) maintaining that the social worker has a prominent role in the macro culture to sway attitudes, beliefs and values about women experiencing stillbirth. This view is congruent with social work values such as advocacy, social change and self-determination. Therefore social workers are in an ideal position to study women's experiences after a loss. The study offers a discussion on these experiences.

GOALS OF THE STUDY

The first goal of the study was to gain a better understanding of the psychosocial implications surrounding stillbirth for the mother and her family. A thorough understanding of these implications would result in better guidelines being provided for social work intervention from the crisis intervention perspective. The second goal was to establish whether the crisis intervention as preferred intervention method was effective and could be recommended when working with bereaved mothers.1

METHODOLOGY AND RESEARCH DESIGN

A combination of quantitative and qualitative research approaches was used in an exploratory and descriptive design to provide a detailed description of the psychosocial experiences and implications of stillbirth. The exploratory design generally refers to the “what” question and the descriptive design refers to the “how” (Mouton, 2001 :53). Purposive sampling techniques, as part of non-probability sampling methods, were used for this research. The overall hypothesis of the study is: “The loss of a fetus/baby has long-term psychosocial implications for the mother and her family as perceived by the mother and proper social work support is needed to facilitate the grief process during the crisis period as well as the adjustment period thereafter”.

This study explores and describes the experiences of 25 mothers who had experienced a stillbirth, and was conducted along the guidelines of the Safe Passage Study (www.safepassagestudy.org) in South Africa. The mothers' feelings about the stillbirth at least 6 months, but no later than 18 months, after the event were examined, as well as its impact on relationships with partners and other children. All the participants received crisis intervention within a week of the loss, and by seeing the participants 6-18 months later it was possible to evaluate the self-reported effectiveness ofthis crisis intervention. A questionnaire was used to obtain demographic (quantitative) data and a semi-structured questionnaire, based on information from literature, was administered during individual interviews (De Vos, Strydom, Fouché & Delport, 2005:296).

Different coping mechanisms were explored by means of the questionnaire, with special focus on seeing, holding and taking photographs of the baby. Lastly, attention was given to feelings regarding medical care, autopsy and support from the community.

Prior to these semi-structured interviews, informed consent was obtained from each participant before the research process continued. The study was approved by the Health Research Ethics Committee, Stellenbosch University (N10/09/313).

RESULTS OF THE STUDY

Demographics

A total of 25 respondents were recruited and their details analyzed. Table 1 shows the demographic information of the affected mothers.

TABLE 1.

SOCIO-ECONOMIC FACTORS INDICATED IN PERCENTAGES

| Age | Frequency (n = 25) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Less than 20 years | 3 | 12 |

| 20 - 29 years | 14 | 56 |

| 30 - 39 years | 8 | 32 |

| Language | ||

| Afrikaans | 19 | 76 |

| English | 2 | 8 |

| Other | 4 | 16 |

| Relationship status during loss | ||

| Married | 7 | 28 |

| Not married, living together | 10 | 40 |

| Not married, living separately | 8 | 32 |

| Length of current relationship | ||

| 1 - 5 years | 18 | 72 |

| 6 - 10 years | 3 | 12 |

| 11 - 15 years | 2 | 8 |

| 16 and longer | 2 | 8 |

| Educational level | ||

| Primary | 6 | 24 |

| Secondary | 17 | 68 |

| College & university | 2 | 8 |

| Occupation | ||

| Working | 14 | 56 |

| Not working | 11 | 44 |

The age of the mothers ranged from 16 to 39 years (mean 26, 5 ± 6,0), with most of them (56%) in the 20-29 years age group. The majority of mothers were Afrikaans-speaking and had been involved in a relationship for between 1-5 years. This correlates with Erikson's life stage theory where he identified starting and establishing a relationship as an important task of early adulthood (Weiten, 1995:458). Therefore one would expect the duration of the relationship to not exceed five years. Regarding educational levels, Table 1 indicates that most of the mothers had completed a secondary education. It should be noted that not all of the mothers had completed Gr 12. The breakdown of the different grades completed are as follows: Gr. 8-9 (4 participants, 16%), Gr. 10-11 (9 participants, 36%) and Gr 12 (4 participants, 16%). Employment rates follow similar lines, though more mothers (56%) were employed while 44% of mothers were unemployed.

History of loss

Some of the respondents had experienced multiple losses. The sample mean of losses per respondent is 1,36%. Most of the losses, 26, were stillbirths, indicating that one (4%) of the respondents had experienced the tragedy of a stillbirth twice. A stillbirth (SB), or stillborn infant, is an infant who is potentially viable but is born with no signs of life. Potentially viable means that the infant would have had a reasonable chance of surviving had it been born alive. Stillbirths are sometimes referred to as intra-uterine deaths or fetal deaths (Woods, Pattinson & Greenfield, 2010). The other losses were one ectopic pregnancy, six miscarriages and one infant death. This is worth mentioning as it can have an impact on respondents’ grief reactions. A woman who has experienced a perinatal loss may not perceive a subsequent pregnancy in a typical fashion, and may have ambivalent feelings and doubts, with concerns that another loss could occur (Callister, 2006:23; Cacciatore, 2010:142; McCoyd, 2010:144).

Psychosocial impact

A psychosocial problem is of a multiple and complex nature pertaining to the social functioning of individuals or to the social and organizational functioning of larger social systems which are affected by, among others, personality disorders or mental illnesses, inadequate role performance and life transitions involving developmental changes, and crises as well as communication and relationship difficulties (Terminology Committee for Social Work, 1995:50).

Feelings and emotions

Seven subthemes with regards to emotions experienced by participants six or more months after the loss were identified. The percentage is an indication of how many participants had the same experience, and several participants displayed emotions at more than one subtheme. The subthemes were:

• Ambivalent emotions

Four (16%) participants were trying to geton with life while in contrast, 11 (42%) of the participants mentioned that they were still crying a lot openly or that they were trying to cry privately, as can be seen from the following excerpts:

“I have moved on. That's why I'm trying for a new baby now”.

“I don't cry physically, but I'm crying inside myself. Nobody can see me”.

“I still sometimes blame myself for her death, even though I got the autopsy result back”.

• Reliving the circumstances surrounding the stillbirth

Three (12%) participants were still reliving the circumstances surrounding the stillbirth:

“There is still that longing even though it happened a year and a half ago. I still relive the labour and those moments afterwards”.

• Constant triggers

Ten (40%) participants found constant triggers including seeing other healthy babies, hearing of other stillbirths and anniversary dates difficult to cope with:

“When I look at my friends’ babies, then I feel jealous”.

• Role of family and friends

Participants mentioned that the role of family and friends was important. Two (8%) of the participants experienced pressure from family and friends to fall pregnant again. Lack of continuous support was also mentioned by one (4%) participant. Four (16%) of the participants indicated that they felt their family and friends understood them and gave positive support. Stringham, Riley and Ross (1982) pointed out that sometimes family members and friends do not respond because they feel they are supportive by protecting them from being uncomfortably when dealing with the loss. Perhaps they are told by someone to refrain from calling the bereaved parents so as not to upset them. They avoid the mother or grow impatient with her continued sadness (Stringham et al., 1982). Alternatively they may be pressured to “move on”. One participant observed:

“My mother mentioned that it's almost four years and she doesn't have a grandchild yet”.

• Constant triggers

Ten (40%) participants found constant triggers including seeing other healthy babies, hearing of other stillbirths and anniversary dates difficult to cope with:

“When I look at my friends’ babies, then I feel jealous”.

• Role of family and friends

Participants mentioned that the role of family and friends was important. Two (8%) of the participants experienced pressure from family and friends to fall pregnant again. Lack of continuous support was also mentioned by one (4%) participant. Four (16%) of the participants indicated that they felt their family and friends understood them and gave positive support. Stringham et al., (1982) pointed out that sometimes family members and friends do not respond because they feel they are supportive by protecting them from being uncomfortably when dealing with the loss. Perhaps they are told by someone to refrain from calling the bereaved parents so as not to upset them. They avoid the mother or grow impatient with her continued sadness (Stringham et al., 1982). Alternatively they may be pressured to “move on”. One participant observed:

“My mother mentioned that it's almost four years and she doesn't have a grandchild yet”.

• Rumination

Five (20%) of the participants were still thinking of their baby every day since the loss:

“I still think of my baby every day, how it would be if he was alive”.

“It is almost two years now, but the thought is still there, it will never go away”.

• Coping mechanisms (positive and negative)

The mothers spoke about the complexities of coping, avoidance, acceptance and the recognition of the loss. Eleven (44%) participants displayed positive coping mechanisms:

“If I don't think of my loss, I don't need to grieve”.

“I thought if I take a few tablets, mix them and drink them, that it will help me to forget“.

“I started using dagga again to help me sleep at night and to help me forget”.

“I made peace with it, it's God's will”.

• Subsequent pregnancies

Six (24%) participants were fearful of losing another baby or of not being able to have a baby again. Furthermore one (4%) participant suffered a subsequent loss and because of the fear of yet another loss, mentioned that she was now avoiding falling pregnant. This correlates with views of Mahan and Calica (1997:16) that there might be a pervading sense of anxiety and insecurity, ambivalence and doubt, with concern that the loss of another child will occur. The “vulnerable child” syndrome, where parents are overprotective of a surviving child, can easily occur:

“I feel excited but not as excited as the first pregnancy, I'm afraid of another loss”.

“I don't want another child because I don 't want to go through the pain again”.

To furtherexplore the psychosocial implications of a stillbirth on a mother, current thoughts and thoughts directly after the loss were reflected on. Table 2 presents a summary of important statements.

TABLE 2.

COMPARING THOUGHTS EXPERIENCED DIRECTLY AFTER THE LOSS AND CURRENT THOUGHTS (N=25)

| Yes - I did experience it | No - I did not experience it | I am still having these thoughts | |

|---|---|---|---|

| I am afraid to fall pregnant again. | 21 (84%) | 4(16%) | 12 (48%) |

| I wanted to fall pregnant again as soon as possible. | 6 (24%) | 19 (76%) | 10 (40%) |

| I feared another loss. | 21 (84%) | 4 (16%) | 19 (76%) |

| When I saw other babies, I longed for my own baby. | 23 (92%) | 2 (8%) | 22 (88%) |

| I have/had nightmares about my baby | 12 (48%) | 13 (52%) | 7 (28%) |

| I had thoughts of committing suicide. | 7 (28%) | 18 (72%) | 3 (12%) |

| I felt nobody understood me or cared for me. | 15 (60%) | 10 (40%) | 8 (32%) |

| I had thought of stealing another baby. | 1 (4%) | 24 (96%) | 0 (0%) |

| I avoided other babies. | 13 (52%) | 12 (48%) | 5 (20%) |

| I was unable to pack my baby's clothes away - left it just like it was for a very long time. | 16 (64%) | 7 (28%) | 8 (32%) |

| I tried to be strong and not show my hurt. | 20 (80%) | 3 (12%) | 17 (68%) |

Twenty-one (84%) of the respondents were afraid of falling pregnant again. Twelve (48%) participants were still afraid of falling pregnant even though it was more than six months later. According to table 2, six (24%) of the participants wanted to fall pregnant again as soon as possible.

Table 2 illustrates that 23 (92%) participants longed for a baby when they saw other babies shortly after their own loss, while 22 (88%) participants still felt the same way even though six months or more have passed. Table 2 illustrates that 12 (48%) participants had nightmares about their babies shortly after the loss, with seven (28%) of the participants still doing so. Seven (28%) participants had considered suicide in the past, while three (12%) participants still had such thoughts. This correlates with Hughes and Riches, (2003) observation on pathological grief. They identified two types of pathological grief: prolonged grief and absent grief. Thoughts of suicide resort under prolonged grief, when no improvement is noted after six months.

Fifteen (60%) of the participants felt that nobody understood their loss, with eight (32%) participants still feeling this way. Table 2 shows that 16 (64%) participants were unable to pack away the baby clothes, while eight (32%) participants were still unable to pack away the clothes, six months or more after the loss. Finally 20 (80%) participants tried to be strong and not show any hurt. Seventeen (68%) participants were still doing this. According to Hutti (2005:633) family members do not know how to respond appropriately and the bereaved mother/couple tend to pretend that they are coping well.

Relationships, crisisintervention and coping skills

The following changes in their relationships were identified by participants.

Problems or changes in relationship after the stillbirth

Six problems or changes were identified:

(i) No changes in relationship

Five (20%) participants experienced continued stability in their relationship. According to Wallerstedt and Higgins (1996:389) society's expectations that the father remain stoic and strong may affect his grief, because he responds in a manner he feels the culture demands. This may contribute to the fact that no significant changes took place in the relationship:

“We were alright with each other after the loss, nothing changed”.

“He still came to visit and nothing changed between us”.

(ii) Communication

Communication improved in the case of seven (28%) participants, while nine (36%) participants were talking less, especially when their partner did not want to talk about it:

“He never spoke about it or shared his feelings about it”.

(iii) Insecurity

Two changes were identified. “Fear of breaking up” was identified by two (8%) participants. For one (4%) participant the stillbirth created insecurity in their relationship because of extra tension in the relationship:

“Because now I lost the baby and he won't like that. Maybe he will leave me”.

“The stillbirth created tension in our relationship”.

(iv) Fury or blame directed at each other or oneself

Four (16%) participants’ partners were blaming them for the stillbirth. Three (12%) participants themselves had feelings of guilt:

“He was angry towards me for having a stillbirth. I could see it in his behaviour”. “He made me feel guilty by saying that I shouldn't have picked up heavy things”.

(v) Poor coping mechanisms

Two (8%) participants’ partners started drinking heavily, which was detrimental to the relationship negatively:

“He started drinking heavily”.

(vi) Wanted distance in the relationship

Four (16%) participants experienced a temporary distance in their relationship. Two (8%) participants’ relationships ended after the stillbirth:

“He stayed away for three months. He said he needed some time alone”.

“I ignored him and told him that there is nothing holding us together and that it's the end of the relationship”.

The abovementioned experiences of participants demonstrate that more than half, i.e. four, of the experiences carry a negative connotation, illustrating a negative change in a relationship. This correlates with Borg and Lasker (1981:85) who mentioned that many couples experience tensions after a stillbirth. They also observed that these tensions usually fade eventually, which explains the seven (28%) participants experiencing improved communication.

The role of a crisis intervention sessions

Twenty-three (92%) of the participants had received a crisis intervention session shortly after the loss, while two (8%) had not received any such intervention. The women who had been able to express their emotional reactions right after the death of the child had a shorter period of insufficiency compared to those who only suppressed their feelings (Wretmark, 1993:56).

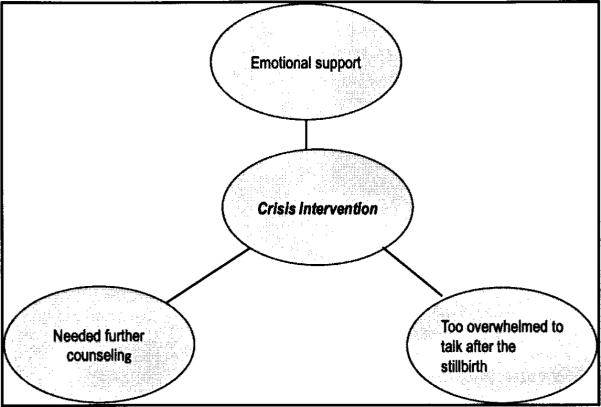

Participants’ views on how they had experienced the crisis intervention session with a social worker at the hospital, at work or the social worker at the Safe Passage Study were analyzed. Figure 1 illustrates the three main aspects which will be discussed:

FIGURE 1.

THREE MAIN ASPECTS IDENTIFIED REGARDING CRISIS INTERVENTION

For sixty-four percent (64%) of participants in this study, crisis intervention was beneficial because it gave them emotional support. They felt encouraged by the support and also indicated that the empathic approach helped them very much.

“I could talk to somebody who understands me”.

“Yes, it did encourage us and it gave us some hope. We felt we didn't need to worry about anything because there is somebody close to us”.

“Most people, even my family, were afraid to speak to me, so I enjoyed the interest shown in me and the opportunity to talk about how I'm feeling”.

Eight (8%) percent of mothers felt that the crisis support was very beneficial but that they needed more support.

“It helped me a lot, but only for a week, and then I felt so sad again. I wanted more sessions with the social worker”.

Twenty-eight percent (28%) thought the idea of crisis intervention was good, but wanted to be approached only a few days after the death of their baby as they had felt too overwhelmed to talk directly after the stillbirth delivery. (The third premise for the Crisis-in-Context theory model concerns time (Myer & Moore, 2006:84.) Literature (Bronfenbrenner, 1995; Brewin, 2001) validates the need to include the element of time in crisis theory. Early beliefs held that an event has varying degrees of impact on an individual's functioning and this impact decreases with the passage of time. Caplan (1961) was of the opinion that time played an important role in recovery from a crisis. Two participants observed:

“The idea is good, but the timing was not. It was too soon. Maybe just a day or two later would be better”.

“No, it was too soon after the stillbirth. I can't recall anything which we have spoken about”.

Psychosocial implications for other areas of the mothers’ lives

To establish the psychosocial implications of a stillbirth in other areas of the mothers’ lives, the following important criteria were explored, as displayed in table 3. Table 3 displays the criteria explored:

TABLE 3.

RELATIONSHIPS, CRISIS INTERVENTION AND COPING SKILLS

| Relationships, crisis-intervention and coping skills | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

| Reaction towards other children after the loss | ||

| I found it difficult to react to their emotional needs | 9 | 36 |

| I neglected them for a period | 8 | 32 |

| I could, as in the past, satisfy their needs | 6 | 24 |

| They irritated me easily | 7 | 28 |

| I did not know how to explain the death | 4 | 16 |

| Caring for my children helped me to deal with the loss | 6 | 24 |

| I appreciate my children much more now | 11 | 44 |

| Severity of crisis as seen by participant | ||

| I didn't perceive my loss as a crisis | 1 | 4 |

| I perceived my loss as a slight crisis | 4 | 16 |

| I saw the loss of my baby as a crisis and needed help | 18 | 72 |

| I perceived my loss as a severe crisis | 2 | 8 |

| Importance of seeing baby | ||

| Longing to see baby | 19 | 76 |

| Only wanted to see baby briefly | 1 | 4 |

| Not after birth, too overwhelmed | 1 | 4 |

| No, only at funeral | 1 | 4 |

| No, never | 3 | 12 |

| Persons who assisted most in the bereavement process | ||

| Mother/grandmother | 7 | 28 |

| Husband /partner | 6 | 24 |

| Social worker | 5 | 20 |

| Sister/ friend with same experience | 3 | 15 |

| Family | 2 | 8 |

| Friend | 1 | 4 |

| Church | 1 | 4 |

| Reactions of people in the community | ||

| Positive reactions: Supportive | 7 | 28 |

| Negative reactions: Teased | 3 | 12 |

| Negative reactions: Mentioned subsequent pregnancies | 10 | 40 |

| Negative reactions: Avoidance | 5 | 20 |

The majority of participants made negative statements regarding relating to their surviving children, for instance by finding it difficult to react to their children's emotional needs, or neglecting their children for a period. They either ignored the children or sent them away to stay elsewhere until they themselves felt better.

One goal of the study was to investigate and gain information regarding the experiences and perceptions of mothers who had suffered a stillbirth. Therefore participants were asked to rate the severity of the loss. The majority of participants indicated their loss as a crisis and needed help and support. Only one participant mentioned that the stillbirth wasn't a crisis to her. Table 3 clearly shows that a stillbirth can be perceived as a crisis and meaningful support could help the individual to deal with it. This concurs with the theory of crisis intervention in social work by Bordow and Porritt (1979:253). They mentioned that intervention involved assessment and action as judged necessary on three fronts: (1) Practical support involved such activities as assistance with making contact with families, and negotiations with employers about return to work. (2) Emotional support was provided by further exploration of emotional reactions to the traumatic events and exploration and clarification of subsequent concerns as these arose. Constructive, problem-oriented, non-blaming coping behaviour was encouraged. (3) Social support was fostered by encouraging family and friends to keep regular contact and also to listen to, accept and try to understand the patient's concerns.

According to Gilliland and James (1993:4), individuals can react in any one of three ways to a crisis. Under ideal circumstances, many people can cope effectively with a crisis by themselves and develop strength from the experience. They grow in a positive manner and come out of the crisis both stronger and more compassionate. Other people appear to survive the crisis, by blocking the hurtful effects from their consciousness, only to have it haunt them in innumerable ways throughout the rest of their lives. Lastly there are those who break down psychologically at the onset of the crisis and need immediate and intensive assistance. Table 3 shows that, as Gilliland and James (1993) mentioned, the majority of participants expressed the need for support to manage their crisis.

Table 3 shows a few outcomes regarding the viewing of the stillborn baby after birth, and it is clear that the majority of participants wanted to see their babies. Participants were asked who helped them the most during their bereavement process and were currently still helping them. Table 3 illustrates that seven (28%) participants mentioned that their mother or grandmother gave them the most support, while six (24%) indicated that they received support from their husband/partner and five (20%) from a social worker.

Some distressing evidence came to light during this study regarding community support. Only seven (28%) mothers received support from community members. Eighteen (72%) mothers received negative responses in the form of teasing, avoidance and mentioning subsequent pregnancies soon after the loss.

According to Stringham et al. (1982:327), support groups give women an opportunity to share their feelings in an atmosphere of acceptance and understanding, to realize that their grief was not unusual or abnormal and to meet others who were resolving a loss. The study explored attitudes towards support groups. Table 3 indicates that none of the participants attended support groups as no support was available in the area. Five (20%) participants mentioned that they did not see the necessity or benefit of such a group while 20 (80%) of the participants would advise someone to attend such a group.

DISCUSSION

Stillbirth is increasingly recognized as a major life event, encompassing complex aspects of coping. We interviewed bereaved mothers following stillbirth to understand their coping process. Most women (14/25) were in their 20s. Ambivalent feelings, constant triggers, memories of the stillbirth, coping mechanisms, subsequent pregnancies and the role of the family all appear to be significant factors when the long-term emotional impact on the bereaved mother was explored.

Findings indicated that the life stage during which most of the participants fell pregnant, is generally that time when individuals’ energy is focused on intimate relationships, learning to live with a marriage partner, starting a family and managing a home. A stillbirth during this time can thus have a significant impact on the mothers’ emotional well-being. For young women under the age of 20 years, it can be extremely stressful as the mother is still searching for her own identity and probably not mature enough to deal with the impact of such a loss.

The home language distribution of the study group correlates with the fact that people living in the designated study area belong to the Brown culture group, and are mostly Afrikaans-speaking. It emerged that the unemployment rate is high and that only 24% (6/25) of the mothers matriculated or had a tertiary education which could help with job seeking.

Although these issues were all addressed during the crisis intervention period, it is suggested that owing to the severe emotional ramifications of stillbirth, long-term emotions persist and not one of the participants were symptom/grief-free six months later. Primary reasons for not wanting to fall pregnant again, as indicated by participants, include that they did not feel themselves strong enough to go through another loss and to relive all the emotions of fear, anger, denial, guilt and worthlessness.

The final findings focused on any positive or negative changes in relationships after the stillbirth. Two-thirds of the participants identified negative communication, insecurity, fury or blame directed at one another, poor coping mechanisms and a need for distance in the relationship. Another conclusion of the study is that stillbirth influenced the participants’ relationships with their other children in different ways. Three major groups could be identified, namely a third of the participants who found it difficult to react to their children's emotional needs, while mainly another third of participants acknowledged that they had neglected their children for a period. The last group, a little more than a third, mentioned that they appreciated their children much more now.

The majority, almost three-quarters, of the participants experienced the stillbirth of their baby as a crisis and felt the need for help from somebody. Most of the participants mentioned that they needed help from a professional person. In evaluating the highly emotional topic of seeing, holding and taking photos of their babies the majority of the participants expressed that they had wanted to see their baby and longed for this.

It can be concluded that bereaved mothers tend to find support in their mothers/grandmothers or another female rather than in their partners. This may be because the partner is going through his own grief and healing process. Although they need to grieve and heal together, it is important to heal individually as well. Nearly all the participants, except two, had a crisis intervention session with a social worker shortly after the stillbirth. Participants were asked to indicate how they had experienced the crisis intervention session with the social worker from the hospital, from their place of employment or the social worker at the Safe Passage Study. The majority of participants reported that the emotional support during the crisis intervention was very valuable. Three participants had experienced empathy, felt encouraged and appreciated the objectiveness of the support. Some participants mentioned that they still had a need for ongoing counselling. A smaller, but significant number of participants mentioned that they had not found the crisis intervention approach positive at the time, as they were still too over whelmed.

Findings show that crisis intervention as social work method is highly recommended by bereaved parents themselves and that they found it valuable soon after the stillbirth. These findings serve as potential mechanisms on how crisis intervention as method in social work can be used to assist patients who have experienced a stillbirth, and assist the family to adjust constructively. Another important conclusion is that for some individuals ongoing counseling and support are needed, with crisis intervention being only the first step preceding further support.

The majority of participants reported that they had received negative reactions from people in the community. These included that they were teased; they were told that they could have children again and some people felt uncomfortable in their presence and avoided them. Positive reactions which included support and understanding were experienced by only seven participants.

The key conclusions to be drawn from these findings are that a stillbirth creates a severe sense of instability and is perceived as a crisis. Bereaved mothers need immediate support and intensive assistance at the onset of the crisis, when. crisis intervention as method in social work can be very advantageous.

The majority of mothers experienced their loss as a crisis and needed help from a professional. The study emphasizes the importance of social workers being aware that the stillbirth causes tension between partners- and in family relationships. Support from a social worker is essential, allowing bereaved mothers to feel empowered and encouraged to grieve openly for their stillborn babies - much needed in an environment where a stillbirth is regarded as a silent birth.

Support from members in the community is generally insufficient, making stillbirth a “silent loss“ or a “disenfranchised loss“. This reiterates the significance of education and support. Unfortunately it is not often talked about, and is not widely reported on in the media. It might be easier to find support when one has the means to get it, but because many stillbirths take place in less privileged socio-economic areas, circumstances are not always conducive “to be able to grieve“.

RECOMMENDATIONS.

Crisis intervention is a positive social work intervention to use when dealing with a bereaved mother and family after experiencing a stillbirth. Care must be taken to provide this intervention as soon as possible after the stillbirth.

Because findings clearly show that crisis intervention alone is not sufficient, the social worker needs to have a system in place where follow-up interventions can take place, whether telephonically or in an individual or couple session. This will take place, whether telephonically or in an individual or couple session. This will take place after crisis intervention during the adjustment phase.

The social worker should equip the bereaved mother/couple with skills and techniques to work through feelings of shock, denial and anger, which form the first stages of the grief process. Social workers should assess and emphasize possible activities that could help the mother cope better with her loss.

Special attention needs to be given by the social worker not only to the bereaved mother during crisis intervention, but also to the partner or husband. It is important to not overlook the partner/husband's grief and his specific grief reactions.

The social worker needs to be aware of the socio-economic status of the bereaved mother while engaged in crisis intervention. This can be helpful when assessing the mother's attitude towards grief and her ability to grieve without other constraints.

The women's determination to complete the interview supports the contention that this study offered women a rare opportunity to talk about their loss and a chance to help other families in future. This appeared to give the women a sense of closure. The mothers had no further questions after the interviews.

The social worker needs to be aware of her/his own emotions regarding stillbirth in order to stay empathetic and objective during support.

In light of the results of the investigation into the psychosocial implications of stillbirth on a mother and her family, it is suggested that further research be done:

There is a need for more qualitative data documenting cultural influences, for there is a paucity of research in this area. Although a good foundation has been laid in this study pertaining to the effects of a stillbirth on the relationship between the bereaved mother and father, it would be beneficial to conduct a long-term study about the effects of stillbirth on the marital relationship with special focus on communication, blame and how subsequent pregnancies could be handled.

- Social workers should take the three main themes from the qualitative research into consideration when dealing with the impact of a stillbirth and should equip the mother to be aware of:

- - The need for validation of the loss and bereavement

- - The importance of internal and external recognition ofthe baby's identity

- - The imperative for social support and compassionate interventions

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Acknowledgements are rendered to the Safe Passage Study, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Stellenbosch University for helping to obtain the cooperation of the participants and for releasing a list of possible participants, and to all co-authors for their help and support. We would like to extend our gratitude to all the mothers who participated in the study.

Footnotes

This research was funded by the following grants from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development: UOl HD055154, UOl HD045935, UOl HD055155, UOI HD045991, and UOI AA016501.

Contributor Information

Melanie Human, Stel/enbosch University, Tygerberg, South Africa.

Sulina Green, Department of Social Work, Stel/enbosch University; Stellenbosch, South Africa.

Coen Groenewald, Stel/enbosch University, Tygerberg, South Africa.

Richard D. Goldstein, Department of Psychosocial Oncology and Palliative Care, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA, USA

Hannah C. Kinney, Department of Pathology, Children's Hospital Boston and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, in collaboration with the PASS Network.

Hein J. Odendaal, Stel/enbosch University, Tygerberg, South Africa.

REFERENCES

- BORDOW S, PORRITT D. An experimental evaluation of crisis intervention. Social Science & Medicine. 1979;13A:251–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BORG S, LASKER J. When pregnancy fails: families coping with miscarriage, stillbirth and infant death. Beacon Press Books; Boston: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- BREWIN CR. Cognitive and emotional reactions to traumatic events: implications for short-term interventions. Advances in Mind-Body Medicine. 2001;17:160–196. doi: 10.1054/ambm.2000.0308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRIER N. Grief following miscarriage: a comprehensive review of the literature. Journal of Women's Health. 2008;17(3):451–464. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRONFENBRENNER U. Developmental ecology through space and time: a future perspective. In: MOEN P, ELDER GH( Jr, LUSCHER K, editors. Examining lives in context: Perspectives on the ecology of human development. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 1995. pp. 619–647. [Google Scholar]

- BROWNLEE K, OIKONEN J. Toward a theoretical framework for perinatal bereavement. British Journal of Social Work. 2004;34(4):517–529. [Google Scholar]

- CACCIATORE J. The silent birth: a feminist perspective. Social Work. 2009;54(1):91–95. doi: 10.1093/sw/54.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CACCIATORE J. Stillbirth: patient-centred psychosocial care. Clinical Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2010;53(3):691–699. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e3181eba1c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CALLISTER LC. Perinatal loss: a family perspective. Journal of Perinatal Neonatal Nursing. 2006;20(3):227–234. doi: 10.1097/00005237-200607000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAPITULO KL. Evidence for healing interventions with perinatal bereavement. American Journal of Maternal Child Nursing. 2005;30(6):389–396. doi: 10.1097/00005721-200511000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAPLAN G. An approach to community mental health. Grune & Stratton; New York: 1961. [Google Scholar]

- CHAN MF, LOU FL, ARTHUR DG, CAO FL, WU LH, LI P, LUI L. Investigating factors associate to nurses' attitudes towards perinatal bereavement care. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2008;17(4):509–518. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.02007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DE MONTIGNY F, BEAUDET L, DUMAS L. A baby has died: the impact of perinatal loss on family social networks. Journal of Obstetric Gynecological and Neonatal Nursing. 1999;28(2):151–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1999.tb01979.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DE VOS AS, STRYDOM H, FOUCHE CB, DELPORT CSL. Research at grass roots. For the social sciences and human service professions. Van Schaik Publishers; Pretoria: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- GILLILAND BE, JAMES RK. Crisis intervention strategies. Brooks/Cole Publishing Company; California: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- HUGHES P, RICHES S. Psychological aspects of perinatal loss. Current Opinion in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2003;15(2):107–111. doi: 10.1097/00001703-200304000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUMAN M. Master's Thesis. Stellenbosch University; Stellenbosch: 2013. Psychosocial implications of a stillbirth for the mother and her family: a crisis-intervention approach. [Google Scholar]

- HUTTI MH. Social and professional support needs of families after perinatal loss. Journal of Obstetric Gynecological and Neonatal Nursing. 2005;34(5):630–638. doi: 10.1177/0884217505279998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KELLNER KR, BEST EK, CHESBOROUGH S, DONNELLY W, GREEN M. Perinatal mortality counseling program for families who experience a stillbirth. Death Studies. 1981;5(1):29–35. doi: 10.1080/07481188108252075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIRK PE. Psychological effects and management of perinatal loss. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1984;149(1):46–51. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(84)90290-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIRKLEY-BEST E, KELLNER KR. The forgotten grief: a review of the psychology of stillbirth. American Journal of Orthopsychiatries. 1982;52(3):420–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1982.tb01428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAHAN CK, CALICA J. Perinatal loss: considerations in social work practice. Social Work in Health Care. 1997;24(3/4):141–152. doi: 10.1300/J010v24n03_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCOYD JLM. A bio-psycho-social assessment of maternal attachment in pregnancy and fetal loss. Revista De Asistenta Sociala. 2010;IX(2):131–147. [Google Scholar]

- MODIBA L, NOLTE AGW. The experiences of mothers who lost a baby during pregnancy. Health SA Gesondheid. 2007;12(2):3–13. [Google Scholar]

- MOUTON J. How to succeed in your master's & doctoral studies: a South African guide and resource book Pretoria. Van Schaik Publishers; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- MYER RA, MOORE HB. Crisis in context theory: an ecological model. Journal of Counseling & Development. 2006;84(2):139–147. [Google Scholar]

- SHEAFOR BW, HOREJSI CR, HOREJSI GA. Techniques and guidelines for social work practice. Allyn and Bacon; United States of America: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- STRINGHAM JG, RILEY JH, ROSS A. Silent birth: mourning a stillborn baby. Social Work. 1982;27(4):322–327. doi: 10.1093/sw/27.4.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TERMINOLOGY COMMITEE FOR SOCIAL WORK . New dictionary ofsocial work. CTP Book Printers; Cape Town: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- WALLERSTEDT RNC, HIGGINS P. Facilitating perinatal grieving between the mother and the father. Journal of Obstetric Gynecological and Neonatal Nursing. 1996;25(5):389–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1996.tb02442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEITEN W. Psychology: themes & variations. Brooks/Cole Publishing; United States of America: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- WOODS DL, PATTINSON RC, GREENFIELD DH. [12/05/2014];Saving Mothers and Babies Manual - Perinatal Education Programme. 2010 [Online] Available: http://www.motherchildhealth.org/pdf/healthcare/saving-mothers-and-babies.pdf.

- WRETMARK AA. Perinatal death as a pastoral problem. Almqvist & Wiksell International; Stockholm: 1993. [Google Scholar]