Abstract

Rationale: Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a progressive lung disease of unknown cause that leads to respiratory failure and death within 5 years of diagnosis. Overt respiratory infection and immunosuppression carry a high morbidity and mortality, and polymorphisms in genes related to epithelial integrity and host defense predispose to IPF.

Objectives: To investigate the role of bacteria in the pathogenesis and progression of IPF.

Methods: We prospectively enrolled patients diagnosed with IPF according to international criteria together with healthy smokers, nonsmokers, and subjects with moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease as control subjects. Subjects underwent bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), from which genomic DNA was isolated. The V3–V5 region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene was amplified, allowing quantification of bacterial load and identification of communities by 16S rRNA quantitative polymerase chain reaction and pyrosequencing.

Measurements and Main Results: Sixty-five patients with IPF had double the burden of bacteria in BAL fluid compared with 44 control subjects. Baseline bacterial burden predicted the rate of decline in lung volume and risk of death and associated independently with the rs35705950 polymorphism of the MUC5B mucin gene, a proven host susceptibility factor for IPF. Sequencing yielded 912,883 high-quality reads from all subjects. We identified Haemophilus, Streptococcus, Neisseria, and Veillonella spp. to be more abundant in cases than control subjects. Regression analyses indicated that these specific operational taxonomic units as well as bacterial burden associated independently with IPF.

Conclusions: IPF is characterized by an increased bacterial burden in BAL that predicts decline in lung function and death. Trials of antimicrobial therapy are needed to determine if microbial burden is pathogenic in the disease.

Keywords: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, Muc5b, bacteria, microbiome

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a progressive and fatal disease of unknown cause. Active infection in IPF is known to be associated with high morbidity and mortality, and immunosuppression is deleterious. Although the role of viruses in the pathogenesis and progression of IPF has been investigated, the role of bacteria has not been studied in detail.

What This Study Adds to the Field

Patients with IPF have an increased pulmonary bacterial load compared with matched control subjects, and the load at the time of diagnosis predicts rapidly progressive IPF and an increased risk of mortality. Clinical trials of antimicrobial therapy are needed to determine if microbial burden is causal or not in IPF progression.

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a progressive and fatal disease of unknown cause (1). It is increasing in prevalence (2), has a median survival from diagnosis of 3 years, and carries a worse life expectancy than some cancers (3). IPF occurs primarily in older adults, many of whom have been smokers, and polymorphisms in genes related to epithelial integrity and host defense predispose to the disease (4–8). Epidemiological studies suggest that environmental factors may be integral to the pathogenesis of IPF in genetically susceptible individuals (9).

The minor allele of a polymorphism (rs35705950) in the promoter of the mucin gene MUC5B is a known host factor that confers an increased risk of developing IPF (4, 6, 10). In mice, Muc5b appears essential for normal macrophage function and effective mucociliary clearance of bacteria (11), supporting a potential role for infection as an environmental trigger in susceptible individuals (12). Although viruses may play a part in the initiation and progression of disease and may also be responsible for a proportion of acute exacerbations (13), the role of bacteria in the pathogenesis and progression of IPF has not yet been studied in detail (14). Active infection in IPF is, however, known to carry a high morbidity and mortality (15). In individuals with IPF, immunosuppression is clearly deleterious (16). Treatment-adherent subjects in a large trial of the use of prophylactic cotrimoxazole in IPF experienced a reduction in overt infections and mortality (17).

We therefore investigated the role of bacteria in the pathogenesis and progression of IPF in a substantial prospective case-control study. As IPF often appears against a background of smoking-related lung disease, we included patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and matched numbers of smokers in our control groups. We used sequence-based culture-independent methodologies to quantify both the numbers of bacterial genomes and the community composition of specimens collected by bronchoalveolar lavage. Some of the results of these studies have been previously reported in the form of an abstract (18).

Methods

Study Design

Patients undergoing diagnostic bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) for suspected but previously undiagnosed IPF were prospectively recruited between November 2010 and January 2013. A diagnosis of IPF was made after multidisciplinary team discussion. Only individuals fulfilling currently accepted international criteria were subsequently included in the study (19). Control subjects included nonsmokers and smokers with normal lung function (referred to throughout as healthy control subjects) and individuals with moderate (Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease stage II) COPD and were recruited separately using the same protocols. Subjects were excluded if they had a history of self-reported upper or lower respiratory tract infection, antibiotic use in the prior 3 months, acute IPF exacerbation, or other respiratory disorders. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects, and the study was approved by the local Research Ethics Committee (Ref 10/H0720/12, 00/BA/459E, and 07/H0712/138).

Bronchoscopy

Fiberoptic bronchoscopy with BAL was performed via the oropharyngeal route in accordance with American Thoracic Society guidelines (20). Aliquots of saline, to a total volume of 240 ml, were separately instilled in to a segment of the right middle lobe. The bronchoscopies were all performed according to a standard operating procedure. Post collection, an aliquot of unfiltered and unprocessed BAL was immediately placed on ice then frozen at −80°C by the bronchoscopist. Negative control samples were collected by aspirating buffered saline through the bronchoscope suction channel before bronchoscopy. BAL fluid was examined for the presence of macrophages to confirm access of the alveolar compartment, and the absence of ciliated epithelium was used to exclude large airway contamination.

DNA Extraction

Two 2-ml aliquots of BAL were centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 15 minutes, to pellet cell debris and bacteria, and genomic DNA was then isolated using the MP Bio FastDNA SPIN Kit for Soil (http://www.mpbio.com) as previously described (21).

Genotyping

Genotypes of the MUC5B SNP rs35705950 were determined using TaqMan assays (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). Reactions were performed in 384-well plates, and fluorescence was read using an Applied Biosystems Viia7 Sequence Detection System.

16S rRNA Gene Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction and Pyrosequencing

The V3–V5 region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene was amplified using the 357F forward primer and the 926R reverse primer for both 16S quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) and pyrosequencing as previously described (21). The barcoded pyrosequence reads were processed using QIIME 1.7.0 (22). Initial denoising was performed to remove sequencing errors (23), and PCR-generated artifacts were removed using ChimeraSlayer (24). Sequences were clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at 97% identity (25), aligned to full-length 16S rRNA sequences (26), and assigned a taxonomic identity with the Ribosomal Database Project classifier using the SILVA reference database.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are presented as means (±SD) and categorical variables as proportions. Metastats was used to perform nonparametric t test comparisons of microbial communities between groups (27), with P values corrected for multiple hypotheses testing using the FDR approach of Benjamini and Hochberg. We restricted testing to OTUs that had a differing mean abundance between cases and control subjects of more than 1% of the total. Shannon’s entropy (28) (α diversity index) and weighted and unweighted UniFrac distances (29) (β diversity) were calculated in QIIME. The time-to-event curves were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared with the use of the log-rank test. Differences between subject groups were evaluated with the use of the Mann–Whitney test for continuous variables and Fisher exact test for categorical variables. Spearman rho was used to calculate correlations between continuous variables. The statistical significance of association of variables with a diagnosis of IPF was assessed using a stepwise backward elimination logistic regression process to select among potential covariates for inclusion in the final model. The statistical significance of association of variables with genotypes of the MUC5B SNP rs35705950 (coded 0, 1, and 2) were modeled using multiple permutations of the data (bootstrapping). All analyses were performed with the use of SPSS (version 21) and R (http://cran.r-project.org/). A two-sided P value of less than 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Subjects, Sampling, and Sequencing

Seventy-five patients with suspected IPF and 44 control subjects (27 healthy control subjects and 17 subjects with moderate COPD) (Table 1) were enrolled in the study and underwent bronchoscopy. During the study period, nine further patients with suspected IPF were excluded from enrollment because they reported symptoms of a lower respiratory tract infection or antibiotic usage in the preceding 3 months. A final diagnosis of IPF was made after multidisciplinary team discussion; 10 of the 75 recruited patients did not fulfill the American Thoracic Society diagnostic criteria for IPF and were subsequently excluded from the study (19).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Patients

| Characteristics | IPF (n = 65) | Combined Control Subjects (n = 44) | Subjects with COPD (n = 17) | Healthy Subjects (n = 27) | P Value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 68 (±8.2) | 58.2 (±8.0) | 60 (±8.5) | 58 (±17.6) | < 0.0001 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 15 (23) | 17 (28) | 5 (29) | 12 (44) | NS |

| Smoking (ever vs never), n (%) | 43 (65) | 28 (63) | 17 (100) | 11 (40) | NS |

| FVC, % | 76.5 (±18) | 100 (±14) | 93.0 (±13) | 104.4 (±14) | < 0.0001 |

| FEV1, % | 77 (±15) | 88.5 (±19) | 69.6 (±15) | 100.4 (±12) | < 0.005 |

| Ratio of FEV1 to FVC | 80.0 (±7) | 71.3 (±11) | 59.9 (±9) | 78.6 (±5) | < 0.0001 |

| Carbon monoxide diffusion capacity, % of predicted value | 44.7 (±13) | 78.8 (±18) | 72.3 (±19) | 84.0 (±16) | < 0.0001 |

| O2 saturation, % | 95 (±2) | 97 (±4) | 96 (±6) | 97 (±2) | NS |

| 6-min-walk distance, m | 377.8 (±124) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Inhaled steroid usage | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NS |

| BAL culture positive, n (%) | 5 (7.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | NS |

Definition of abbreviations: BAL = bronchoalveolar lavage; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; IPF = idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; NA = not available, NS = not significant.

Data are means ± SD unless otherwise noted.

P value is comparison between the IPF and combined control group. The table provides the demographics for the subject panels used in the study. Details are provided for IPF cases, subjects with COPD, healthy subjects, as well as combined control subjects (COPD plus healthy subjects).

The remaining 65 subjects with IPF were predominantly men (77%), with a mean age of 68 years, and had moderately severe disease at enrollment (carbon monoxide diffusing capacity [DlCO], 44.7% predicted; FVC, 76.5% predicted). Nine of the 65 subjects with IPF had coexisting emphysema based on high-resolution computed tomography scan, and in all cases the extent of emphysema was less than the extent of fibrosis on computed tomography. The 44 control subjects were matched for smoking history and sex but were younger than the IPF cohort, with a mean age of 58.2 years (Table 1). None of the control group and only four of the subjects with IPF were using inhaled corticosteroids at the time of their assessment.

Bacterial 16S rRNA sequencing was performed on extracted genomic DNA from all 109 subjects, and after denoising, chimera checking, and singleton removal a total of 912,883 high-quality reads remained, with on an average 5,851 reads per sample. To control for bias of per-sample read coverage, we randomly resampled (rarefied) sequences to the same minimum of 796 reads for all subjects. Sequences were then clustered by sequence similarity into OTUs, which are approximately analogous to a bacterial species, and this final dataset was used in all subsequent analyses. There were 464 OTUs identified across the IPF and control panels, and less than 5% of the sequences were unclassifiable by reference to the SILVA reference database. All processing of the samples to DNA was performed by P.L.M. qPCR and sequencing of control subjects and IPF samples were performed together in a single batch, to control for the potential effects of batch and operator variability. The full data set can be downloaded from http://lungen.bioinformatics.ic.ac.uk/data/microbiome_ipf.

Bacterial Burden

First, we explored the differences in BAL bacterial load (burden) between cases versus control subjects. We found that on average, subjects with IPF had 1.9 × 108 copies of the 16S rRNA gene/ml of BAL, which was more than twofold higher than the copy number in control subjects (P < 0.0001). Within the control subjects, there was no significant difference in bacterial load between subjects with COPD and healthy control subjects. The patients with IPF had a significantly higher bacterial burden than both control subgroups (P = 0.006 and P = 0.0007, respectively) (Figure 1). Sputum samples from 20 control subjects taken the day before bronchoscopy demonstrated a mean bacterial load of 3.1 × 109 copies of the 16S rRNA gene/ml, 32 times higher than the subsequent lavage (P < 0.0001). There was no correlation between the bacterial load and either the total or differential BAL cell counts. The negative control samples (sterile saline aspirated through the suction channel of the bronchoscope) yielded a bacterial burden close to or below the lower limit of qPCR quantification (1,000 copies/ml). Although BAL return differed between IPF cases and control subjects (124.4 ml ± 31 vs. 96 ml ± 41; P < 0.001), there was no relationship between bacterial burden and BAL yield (Spearman ρ = −0.027, P = 0.78). Importantly, no ciliated epithelial cells (which may have been indicative of large airway contamination) were seen in the BAL returns.

Figure 1.

Bacterial burden in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) compared with control subjects. Patients with IPF (red) (n = 64) had a significantly higher bacterial burden than subjects with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (green) (n = 17) and the healthy control subjects (blue) (n = 27) (P = 0.006 and P = 0.0007, respectively). The box signifies the 25th and 75th percentiles, and the median is represented by a short line within the box. BAL = bronchoalveolar lavage.

Within the subjects with IPF we found bacterial burden to be associated independently with the rs35705950 polymorphism in the promoter of the mucin gene MUC5B genotype (P = 0.01), with patients possessing a minor allele having a lower bacterial burden (see Figure E1 in the online supplement). There was no correlation between bacterial burden and baseline disease severity, measured by either FVC (Spearman ρ = −0.11, P = 0.49), total lung capacity (Spearman ρ = −0.12, P = 0.49), DlCO (Spearman ρ = −0.20, P = 0.21), or the composite physiologic index (Spearman ρ = 0.06, P = 0.70).

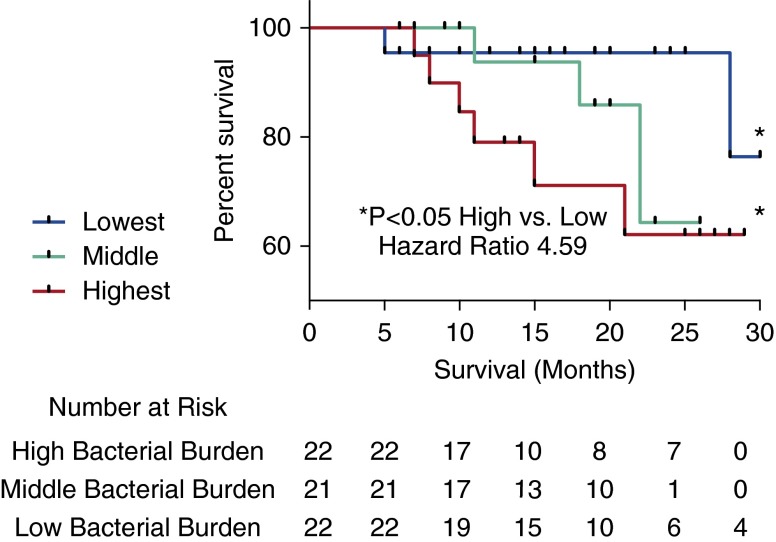

To test for a relationship between bacterial load and disease progression, we partitioned the patients with IPF into groups with progressive or stable disease. As a 6-month decline of greater than 10% in FVC is associated with an increased risk of mortality in IPF (30), we defined disease progression as either a relative decline in FVC of greater than 10% or death. Individuals with IPF whose disease had progressed at 6 months (n = 22) demonstrated a significantly higher BAL bacterial burden when compared with subjects with stable disease (2.35 × 108 ± 1.68 × 108 compared with 1.41 × 108 ± 1.40 × 108) copies of the 16S rRNA gene/ml of BAL; P = 0.02). To investigate this relationship further, we separated the subjects with IPF into tertiles based on the 16S rRNA gene copy number/ml of BAL. Individuals in the top tertile with the highest bacterial burden were at a substantially increased risk of mortality compared with subjects in the bottom tertile (i.e., those with the lowest bacterial burden) (hazard ratio, 4.59; 95% confidence interval, 1.05–20) (Figure 2). There were no significant differences in sex, age, smoking status, or disease severity between the patients with IPF within these tertiles of bacterial burden.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves for time until death. Subjects with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) in the tertile with the highest bacterial load (16S copy number/ml of bronchoalveolar lavage) are shown in red, and were at increased risk of mortality compared with subjects with IPF in the tertile with the lowest bacterial burden, shown in blue (hazard ratio, 4.59; 95% confidence interval, 1.05–20).

Microbial Communities

We then compared the baseline microbiota of the subjects with IPF and the control subjects (Figure 3). Sequencing revealed Streptococcus, representing 30% of total reads, was the most common genus in subjects with IPF, followed by Prevotella (10.9%) and Veillonella (10.6%). In the combined control subjects, Streptococcus also formed the most common genus (27.1% of total reads) followed by Prevotella (11.6%) and Veillonella (7.1%). We found no significant differences in the BAL microbiota between the healthy control subjects and subjects with COPD (Figure 3). The microbial communities of subjects with IPF were by contrast less diverse (Shannon diversity index, 3.81 ± 0.08 vs. 4.11 ± 0.10; P = 0.005) and contained fewer numbers of OTUs (44.89 ± 1.50 vs. 54.33 ± 1.86 OTUs; P < 0.0001) than the control subjects. We discovered in patients compared with control subjects a 3.4-fold increase in sequence reads of a potentially pathogenic Haemophilus sp. (OTU 739) (36.0 ± 7.5 vs. 10.5 sequences ± 1.9 sequences; P < 0.001); a 2.1-fold increase in a Neisseria sp. (OTU 594) (57.9 ± 9.4 vs. 27.5 ± 5.5 sequences; P < 0.01); a 1.4-fold increase in a Streptococcus sp. (OTU 881) (113.6 ± 11.4 vs. 82.2 ± 8.9 sequences; P < 0.05); and a 1.5-fold increase in a Veillonella sp. (OTU 271) (84.8 ± 5.7 vs. 56.6 ± 4.5 sequences; P < 0.001) (Figure 4). There were no demonstrable changes in community structure or composition between patients with IPF with progressive or stable disease, despite the differences in overall bacterial burden. There were no significant differences in the BAL microbiota between the healthy control subjects and subjects with COPD, and exclusion of subjects with COPD from the control panel did not change the differences detected. When our data were analyzed with patients on corticosteroids excluded from the IPF cohort, the observed differences in the microbiota remained unchanged.

Figure 3.

A phylogenetic tree and heatmap of bacterial 16S rRNA sequences grouped by disease status: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and healthy control subjects. This depicts operational taxonomic units (OTUs) with identifiers organized phylogenetically by tree with abundance indicated by the color (darker blue or red more abundant). The OTUs of interest are highlighted in red.

Figure 4.

Differences in bacterial operational taxonomic unit (OTU) frequencies between idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) and control subjects. Box plots showing significant differences (P < 0.01) in OTUs between control subjects (blue) and patients with IPF (red). Triangles represent subjects with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), circles healthy control subjects, and squares subjects with IPF. The box signifies the 25th and 75th percentiles, and the median is represented by a short line within the box.

Standard microbial culture of BAL was positive in five cases of IPF (7.6%) but none of the control subjects. In each instance, the cultured bacterial species were also identified by the pyrosequencing data, although they were not always the most abundant species within the microbiome.

We then examined, using a stepwise logistic regression, whether bacterial burden and the relative abundance of these OTUs were associated independently with a diagnosis of IPF. Age and smoking status were included in the model to control for possible confounding. Total bacterial burden and the numbers of three specific OTUs (Veillonella sp. [OTU 271], Neisseria sp. [OTU 594], and Streptococcus sp. [OTU 881]) all remained significantly associated with a diagnosis of IPF (P = 0.001, 0.007, and 0.01, respectively). The overall R2 was 0.66 with age in the model and was 0.51 without age. The abundance of Haemophilus OTU 739 was strongly correlated with Neisseria OTU 594 (Spearman ρ = 0.42). Removal of Neisseria from the model made Haemophilus OTU 739 significant (P = 0.02; β = 0.038 ± 0.016) with minimal change in the overall multivariate R2 (0.657).

Discussion

In this study we demonstrated that when compared with control subjects, patients with IPF have a higher bacterial load in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and significant differences in the composition and diversity of their microbiota. We have also shown that an increased bacterial load at the time of diagnosis identified patients with more rapidly progressive IPF and a higher risk of mortality.

The baseline bacterial communities we observed in patients with IPF and control subjects contained organisms such as Streptococcus, Prevotella, Fusobacterium, and Haemophilus, which are commonly found in the airways of healthy subjects, subjects with asthma, and patients with COPD (31–34). We discovered differences in specific OTUs between cases and control subjects, notably the presence of more abundant Streptococcus, Haemophilus, Neisseria, and Veillonella spp. in the patients with IPF. This indicated that total bacterial load and the abundances of these specific OTUs provided independent predictors of IPF case status and suggested that potentially pathogenic OTUs may be acting synergistically within a context of an increased bacterial load.

The rs35705950 polymorphism in the promoter of the mucin gene MUC5B confers an increased risk of developing IPF (4) but paradoxically confers a survival benefit among patients with IPF (7). We found bacterial burden to be associated independently with rs35705950 genotype (P = 0.01), with patients possessing a minor allele having a lower bacterial burden, suggesting a direct relationship between host immunity and bacterial load. The more densely populated and less diverse bacterial communities of the lower airways in IPF may provide persistent stimuli for repetitive alveolar injury. The temporal and spatial heterogeneity observed in usual interstitial pneumonia (the histological lesion of IPF) speaks to the likely importance of repetitive injury as a major factor in the pathogenesis of the disease (35). The bacterial communities of the lower airways are a plausible candidate for this trigger, and regional differences in the bacterial microbiome (36) may help explain the distribution of the fibrotic lesions in IPF.

We do not find any association between specific microbes and disease progression. Han and colleagues have recently presented data for the microbiota of individuals with IPF in a retrospective study (37). They demonstrate the most commonly identified bacteria in the lungs of individuals with IPF were Prevotella sp., Veillonella sp., and Escherichia sp., the presence of which we confirmed in our cohort. The authors found that the presence of a specific Streptococcus sp. or Staphylococcus sp. above a statistically modeled threshold was associated with a composite endpoint for disease progression. However, less than half of their patients had either of these bacteria in levels above the threshold, suggesting neither can fully explain disease pathogenesis or progression (38). We are able to confirm the presence of Streptococcus sp. or Staphylococcus sp. in the IPF microbiome, and a longer follow-up period has allowed us to investigate for associations between the microbiome and survival. We demonstrate that although there are clear differences in the IPF microbiome compared with healthy individuals, it is the bacterial load that effects survival.

We cannot not draw any conclusions regarding the causal nature or not of this altered respiratory microbiome in IPF. Trials of antibiotic therapy may help elucidate this. There has recently been a large placebo-controlled multicenter study evaluating the use of Septrin in the broader category of fibrotic idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. This treatment was not well tolerated, and there was ultimately no detectable difference in the primary endpoint. Despite this, in subjects who tolerated Septrin therapy there was a reduction in infections and subsequent mortality. The authors hypothesize that this observation may be a result of Septrin’s antimicrobial effects, but it is difficult to draw conclusions because of its concurrent antiinflammatory actions. However, combined with our data here and the high mortality associated with bacterial respiratory tract infections in IPF, this observation does suggests a more targeted and well-tolerated antibiotic should be trialed in an IPF cohort.

There is a wide variation in the reported qPCR values for bacterial load in BAL, and the absolute quantification is dependent on multiple factors from sampling to processing, hindering comparisons between studies with differing primers and qPCR conditions. The bacterial loads reported here are comparable with other studies (36, 39), and our conclusions are based on relative values between cases and control subjects and those with stable or progressive disease. The inclusion of negative sampling control subjects (sterile saline aspirated through the suction channel of the bronchoscope), which yielded bacterial burden close to or below the lower limit of qPCR quantification, also demonstrates that the qPCR results are not simply artifact from a sampling or processing error.

Our study has a number of limitations. IPF is a disease of the lung parenchyma, whereas we used BAL fluid to sample the distal airways. Direct sequencing of lung tissue may provide further information on the pulmonary microbiome (40), but lung biopsies are undertaken infrequently in IPF, and gathering true healthy control samples would be extremely difficult. We used the oropharyngeal route to pass a bronchoscope into the lungs, and some secretions from the upper airways will have been carried on the tip of the bronchoscope. Any carryover, however, will have been heavily diluted by the 240 ml of BAL fluid. The high percentage of BAL return and an absence of ciliated epithelial cells in BAL fluid (indicative of large airway contamination) provided confidence that our BAL return was primarily derived from the distal airspace. We note that strong similarities have been seen between microbiota identified from BAL fluid and from surgically removed lung tissue in which upper airway contamination was not an issue (36). Most importantly, we used the same protocols and procedures for cases and control subjects, so any contamination will not have systematically influenced our results. Although there is currently no universally adopted approach to minimize potential upper airways carryover, the use of protected BAL fluid, pro-BAL catheters, or protected catheter brushes could help avoid contamination.

Although the combination of 16S rRNA PCR with next-generation sequencing allows the parallel sequencing of large number of samples at relatively low cost and without the need for culture, there are limitations to the technique. The most significant are the biases introduced by primer design, which may select for, or against, particular bacteria (41). A further limitation to our study is that we did not assess for the presence or absence of other potential nonbacterial lung pathogens. Although a substantial study found no evidence of detectable viruses by PCR of BAL fluid from 40 stable patients with IPF (13), it is conceivable that some differences in progression could be due to the presence of respiratory viruses in our sample.

IPF is a fatal progressive disease with a median survival of 2 to 3 years. There are no effective treatments for the illness. We have demonstrated that increased bacterial load at the time of diagnosis identifies patients with more rapidly progressive IPF and a higher risk of mortality. It is not possible to conclude from our results whether the presence of an altered microbiome is the cause or a result of the destruction of the normal lung architecture. Although requiring further validation in larger prospective cohorts, our findings nevertheless provide a strong rationale for trials of antimicrobial therapy in IPF. Such trials will help determine the etiological role of bacteria in the progression of IPF while at the same time investigating a novel potential treatment for a currently intractable and fatal disease.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the late Dr Joseph Footitt, who was instrumental in the study of control subjects.

Footnotes

P.L.M. was an Asmarley Clinical Research Fellow. The project was supported by the Asmarley Trust, the Wellcome Trust, the NIHR Respiratory Disease Biomedical Research Unit at the Royal Brompton and Harefield NHS Foundation Trust, the AHSC Biomedical Research Centre at Imperial College London, and National Institutes of Health grants HL097163 and HL092870. Control samples were collected with support from an unrestricted grant from GlaxoSmithKline, Medical Research Council Program grant G0600879, the NIHR Clinical Lecturer funding scheme (P.M.), and a grant from Pfizer UK. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author Contributions: P.L.M. planned the project, recruited subjects, designed and performed experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript; M.J.C. and S.A.G.W.-O. performed statistical analyses, interpreted the results, and helped write the manuscript; K.E.R. performed experiments and interpreted the results; P.M., S.L.J., A.-M.R., and A.U.W. enrolled subjects and performed the research; E.M. performed the genotyping; M.F.M. and W.O.C.C. conceived the microbiological studies of IPF; T.M.M. conceived the systematic prospective study of patients with IPF; D.A.S. conceived the relationship between MUC5B variant and bacterial burden; M.F.M., W.O.C.C., and T.M.M. planned the project, designed experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed, revised, and approved the manuscript for submission.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201403-0541OC on September 3, 2014

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Maher TM. Wells AU, Laurent GJ. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: multiple causes and multiple mechanisms? Eur Respir J. 2007;30:835–839. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00069307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Navaratnam V, Fleming KM, West J, Smith CJP, Jenkins RG. Fogarty A, Hubbard RB. The rising incidence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in the UK. Thorax. 2011;66:462–467. doi: 10.1136/thx.2010.148031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ley B, Collard HR, King TE, King TE., Jr Clinical course and prediction of survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;183:431–440. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201006-0894CI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seibold MA, Wise AL, Speer MC, Steele MP, Brown KK, Loyd JE, Fingerlin TE, Zhang W, Gudmundsson G, Groshong SD, et al. A common MUC5B promoter polymorphism and pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1503–1512. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1013660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Noth I, Zhang Y, Ma S-F, Flores C, Barber M, Huang Y, Broderick SM, Wade MS, Hysi P, Scuirba J, et al. Genetic variants associated with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis susceptibility and mortality: a genome-wide association study. Lancet Respir Med. 2013;1:309–317. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(13)70045-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fingerlin TE, Murphy E, Zhang W, Peljto AL, Brown KK, Steele MP, Loyd JE, Cosgrove GP, Lynch D, Groshong S, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies multiple susceptibility loci for pulmonary fibrosis. Nat Genet. 2013;45:613–620. doi: 10.1038/ng.2609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peljto AL, Zhang Y, Fingerlin TE, Ma S-F, Garcia JG, Richards TJ, Silveira LJ, Lindell KO, Steele MP, Loyd JE, et al. Association between the MUC5B promoter polymorphism and survival in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. JAMA. 2013;309:2232–2239. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.5827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lawson WE, Loyd JE, Degryse AL. Genetics in pulmonary fibrosis–familial cases provide clues to the pathogenesis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Med Sci. 2011;341:439–443. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31821a9d7a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taskar VS, Coultas DB. Is idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis an environmental disease? Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006;3:293–298. doi: 10.1513/pats.200512-131TK. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stock CJ, Sato H, Fonseca C, Banya WA, Molyneaux PL, Adamali H, Russell A-M, Denton CP, Abraham DJ, Hansell DM, et al. Mucin 5B promoter polymorphism is associated with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis but not with development of lung fibrosis in systemic sclerosis or sarcoidosis. Thorax. 2013;68:436–441. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-201786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roy MG, Livraghi-Butrico A, Fletcher AA, McElwee MM, Evans SE, Boerner RM, Alexander SN, Bellinghausen LK, Song AS, Petrova YM, et al. Muc5b is required for airway defence. Nature. 2014;505:412–416. doi: 10.1038/nature12807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang IV, Luna LG, Cotter J, Talbert J, Leach SM, Kidd R, Turner J, Kummer N, Kervitsky D, Brown KK, et al. The peripheral blood transcriptome identifies the presence and extent of disease in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e37708. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wootton SC, Kim DS, Kondoh Y, Chen E, Lee JS, Song JW, Huh JW, Taniguchi H, Chiu C, Boushey H, et al. Viral infection in acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:1–30. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201010-1752OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Molyneaux PL, Maher TM. The role of infection in the pathogenesis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir Rev. 2013;22:376–381. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00000713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Song JW, Hong S-B, Lim C-M, Koh Y, Kim DS. Acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: incidence, risk factors and outcome. Eur Respir J. 2011;37:356–363. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00159709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raghu G, Anstrom KJ, King TE, Lasky JA, Martinez FJ. Prednisone, azathioprine, and N-acetylcysteine for pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1968–1977. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shulgina L, Cahn AP, Chilvers ER, Parfrey H, Clark AB, Wilson ECF, Twentyman OP, Davison AG, Curtin JJ, Crawford MB, et al. Treating idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis with the addition of co-trimoxazole: a randomised controlled trial. Thorax. 2013;68:155–162. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Molyneaux PL, Russell AM, Cox MJ, Moffatt MF, Cookson WOC, Maher TM. The respiratory microbiome in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis [abstract] Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:A5174. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raghu G, Collard HR, Egan JJ, Martinez FJ, Behr J, Brown KK, Colby TV, Cordier JF, Flaherty KR, Lasky JA, et al. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:788–824. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2009-040GL. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meyer KC, Raghu G, Baughman RP, Brown KK, Costabel U, du Bois RM, Drent M, Haslam PL, Kim DS, Nagai S, et al. An official American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline: the clinical utility of bronchoalveolar lavage cellular analysis in interstitial lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:1004–1014. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201202-0320ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Molyneaux PL, Mallia P, Cox MJ, Footitt J, Willis-Owen SAG, Homola D, Trujillo-Torralbo M-B, Elkin S, Kon OM, Cookson WOC, et al. Outgrowth of the bacterial airway microbiome after rhinovirus exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:1224–1231. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201302-0341OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, Costello EK, Fierer N, Pena AG, Goodrich JK, Gordon JI, et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods. 2010;7:335–336. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quince C, Lanzen A, Curtis TP, Davenport RJ, Hall N, Head IM, Read LF, Sloan WT. Accurate determination of microbial diversity from 454 pyrosequencing data. Nat Methods. 2009;6:639–641. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haas BJ, Gevers D, Earl AM, Feldgarden M, Ward DV, Giannoukos G, Ciulla D, Tabbaa D, Highlander SK, Sodergren E, et al. Chimeric 16S rRNA sequence formation and detection in Sanger and 454-pyrosequenced PCR amplicons. Genome Res. 2011;21:494–504. doi: 10.1101/gr.112730.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Edgar RC. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2460–2461. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caporaso JG, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, DeSantis TZ, Andersen GL, Knight R. PyNAST: a flexible tool for aligning sequences to a template alignment. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:266–267. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.White JR, Nagarajan N, Pop M. Statistical methods for detecting differentially abundant features in clinical metagenomic samples. PLOS Comput Biol. 2009;5:e1000352. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shannon CE. A mathematical theory of communication. ACM SIGMOBILE Mob Comput Commun Rev. 2001;5:3. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lozupone C, Hamady M, Knight R. UniFrac–an online tool for comparing microbial community diversity in a phylogenetic context. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:371. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Collard HR, King TE, Bartelson BB, Vourlekis JS, Schwarz MI, Brown KK. Changes in clinical and physiologic variables predict survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168:538–542. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200211-1311OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hilty M, Burke C, Pedro H, Cardenas P, Bush A, Bossley C, Davies J, Ervine A, Poulter L, Pachter L, et al. Disordered microbial communities in asthmatic airways. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e8578. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cardenas PA, Cooper PJ, Cox MJ, Chico M, Arias C, Moffatt MF, Cookson WO. Upper airways microbiota in antibiotic-naïve wheezing and healthy infants from the tropics of rural Ecuador. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e46803. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang YJ, Kim E, Cox MJ, Brodie EL, Brown R, Wiener-Kronish JP, Lynch SV. A persistent and diverse airway microbiota present during chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations. OMICS. 2010;14:9–59. doi: 10.1089/omi.2009.0100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Charlson ES, Chen J, Custers-Allen R, Bittinger K, Li H, Sinha R, Hwang J, Bushman FD, Collman RG. Disordered microbial communities in the upper respiratory tract of cigarette smokers. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15216. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.King TE, Pardo A, Selman M. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Lancet. 2011;378:1949–1961. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60052-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Erb-Downward JR, Thompson DL, Han MK, Freeman CM, McCloskey L, Schmidt LA, Young VB, Toews GB, Curtis JL, Sundaram B, et al. Analysis of the lung microbiome in the “healthy” smoker and in COPD. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e16384. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Han MK, Zhou Y, Murray S, Tayob N, Noth I, Lama VN, Moore BB, White ES, Flaherty KR, Huffnagle GB, et al. Lung microbiome and disease progression in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: an analysis of the COMET study. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2:548–556. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70069-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Molyneaux PL, Maher TM. Respiratory microbiome in IPF: cause, effect, or biomarker? Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2600:10–11. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70088-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Charlson ES, Bittinger K, Chen J, Diamond JM, Li H, Collman RG, Bushman FD. Assessing bacterial populations in the lung by replicate analysis of samples from the upper and lower respiratory tracts. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e42786. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sze MA, Dimitriu PA, Hayashi S, Elliott WM, McDonough JE, Gosselink JV, Cooper J, Sin DD, Mohn WW, Hogg JC. The lung tissue microbiome in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:1073–1080. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201111-2075OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sim K, Cox MJ, Wopereis H, Martin R, Knol J, Li M-S, Cookson WOCM, Moffatt MF, Kroll JS. Improved detection of bifidobacteria with optimised 16S rRNA-gene based pyrosequencing. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e32543. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]